Abstract

Innovation is a necessary guarantee for the long-term survival of an enterprise, and Research and Development (R&D) is the source of enterprise innovation. In the situation where the government is comprehensively promoting the strategy of manufacturing power and digital China, it is becoming increasingly important for manufacturing enterprises to stimulate enterprise innovation through digital transformation. At the same time, the innovation achievements of enterprises are inseparable from its R&D activities. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to explore the influence mechanism of digital transformation on process innovation performance and product innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises. In this process, this paper puts exploratory R&D capability and exploitative R&D capability as mediating variables into the above research framework. The results show that digital transformation directly promotes the process innovation performance and product innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises. Moreover, the two types of R&D capabilities play the same mediating role in the process of digital transformation boosting enterprise innovation performance, but their indirect mechanisms are different. The above conclusions remain valid after the robustness test. In addition, the heterogeneity test results show that the promotional effect of digital transformation on the innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises has sectoral differences. Only the digital transformation of the mechanical equipment manufacturing sector has a positive effect on two types of innovation performance. In general, the higher the technology content of an enterprises is, the more obviously the digital transformation affects its innovation performance. The above findings have contributed to revealing the specific role and practical significance of Chinese manufacturing enterprises in improving innovation performance based on digital transformation.

1. Introduction

At present, the revolution in science and technology dominated by digital technology is accelerating the digital transformation of people’s social life and modes of production. This provides a prerequisite for promoting China’s economic transformation and the transformation of new and old kinetic energy. The “White Paper on the Development of China’s Digital Economy (2021)” issued by the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology shows that, from 2005 to 2020, the proportion of China’s digital economy in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased from 14.2% to 38.6%. In 2020, despite the effects of COVID-19, China’s digital economy maintained a growth rate of 9.7%, which far outclassed the growth rate of nominal GDP in the corresponding year. With the prominence of the importance of the digital economy, digital transformation has turned into an essential engine to drive the sustained and steady growth of the national economy.

Scholars have carried out considerable research on enterprise digital transformation at the micro-level. However, few studies have been carried out on the impact of digital transformation on enterprise innovation performance. Existing research on enterprise digital transformation mainly concentrates on digital transformation and enterprise financial performance [1,2], digital transformation and enterprise product development [3,4], digital transformation and enterprise management or decision-making [5,6], and digital transformation and enterprise supply chains [7,8,9].

The research on the relationship between enterprise innovation performance and enterprise dimensions mainly includes: the impact of enterprise performance in the capital market on enterprise innovation performance [10,11], for example, Fang et al. focused on the relationship between stock liquidity and corporate innovation, and concluded that the two are negatively correlated; the impact of enterprise scale and various financial performance indicators on enterprise innovation performance [12,13], in which Joana and João proposed that there is a positive correlation between enterprise scale and enterprise innovation, but when it comes to the process innovation tendency and product innovation tendency, it shows effect of heterogeneity; the impact of the characteristics of enterprise management on enterprise innovation performance [14,15], for example, Khan focused on the relationship between female executives and enterprise innovation, and drew the conclusion that the proportion of female executives is negatively correlated with enterprise innovation investment; the impact of the nature of enterprise equity on enterprise innovation performance [16,17], for example, Czarnitzki and Kraft focused on the relationship between the degree of equity dispersion and enterprise innovation, and concluded that the higher the degree of equity dispersion, the higher the level of enterprise innovation.

In addition, enterprise innovation is a dynamic process, which involves process innovation and outcome innovation [18]. Process innovation plays a supporting and decisive role in outcome innovation, and it is the forerunner of outcome innovation. However, most scholars usually regard innovation as a whole when analyzing enterprise innovation, without distinguishing the two, or only focus on the outcome innovation represented by product innovation. They usually ignore the process innovation that can reflect the long-term development potential of the enterprise [19].

In the few studies on the impact of digital transformation on enterprise innovation performance, they mainly focus on the direct relationship between them and the influence of external factors. For example, Luo et al. [20] explored the relationship between digital transformation and innovation performance through fixed-effect regression, and they found that digital transformation enhanced the advantages of enterprises in developing key organizational capabilities. Ferreira et al. [21] discussed the relationship between digital transformation and innovation performance based on a binary regression model, and found that digital transformation enhanced the advantages of adapting to uncertain environments. Marion et al. [22] explored the relationship between digital transformation and enterprise product innovation performance based on a multiple regression model, and concluded that digital transformation helps enterprises form modular product development architecture. Wang et al. [23] and Chen et al. [24], respectively, found that the external competition intensity faced by enterprises and external market orientation positively moderated the relationship between digital transformation and enterprise product innovation performance through structural equation modeling. It can be seen that the above research only considers the impact of digital transformation on innovation performance from the perspective of direct impact and external factors, and does not discuss the internal influencing factors of enterprises.

Therefore, to clarify the impact path of digital transformation on innovation performance, this paper focuses on manufacturing enterprises to analyze the direct impact of digital transformation on manufacturing innovation performance. At the same time, this paper incorporates Research and development (R&D) capability into the research framework to explore the mediating role of R&D capability. In order to further analyze the role of different R&D capabilities, this paper divides R&D capability into exploitative R&D capability and exploratory R&D capability. In addition, from the perspective of innovation content, the enterprise innovation performance is classified into process innovation and product innovation.

Compared with the existing literature, this paper has the following academic contributions. First, in terms of research perspective, this paper takes digital transformation as the starting point to explore its impact on enterprise innovation, and puts two forms of enterprise R&D within the framework of digital transformation and enterprise innovation performance analysis. This broadens the research perspective of enterprise digital transformation. Second, in terms of research content, this paper takes manufacturing enterprises as the research object, and uses text analysis as the main data collection method. In the variable setting, and with the digital transformation as an independent variable, enterprise innovation performance as a dependent variable, enterprise R&D as an intermediary variable, the parallel mediation model is used to analyze the relationship between the three. Third, in terms of practical significance, this paper confirms the fact that digital transformation contributes to the innovation and development of enterprises, tests the heterogeneous intermediary role of exploratory R&D and exploitative R&D in the above process, and reveals the sectoral differences of digital transformation affecting enterprise innovation by segmenting manufacturing enterprises.

The arrangement below is as follows. The Section 2 theoretically deduces the relationship among digital transformation, R&D capability, and innovation performance. It also puts forward the corresponding hypothesis of this paper. The Section 3 describes the parallel mediation model structure, related variables, and data sources. The Section 4 shows the process and results of empirical research. The Section 5 summarizes the conclusions found from the results and gives corresponding policy recommendations.

2. Theoretical Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Digital Transformation and Enterprise Innovation Performance

Digital transformation is a process of dynamic transformation. The process aims to introduce digital technology into enterprise to drive operational and business model change while optimizing production and management. Based on digital technology, a large amount of information input is conducive to the exchange and sharing of information, knowledge, and resources among subjects. This provides more possibilities for enterprise innovation activities. For one thing, the redesign, integration, and upgrading of the production process by digital technology can modularize the original production process. This brings high utilization and high efficiency production processes to enterprises so as to optimize business processes and promote enterprise process innovation. For another thing, the information platform based on digital technology relieves the information asymmetry between enterprises and departments. It stimulates the creativity of enterprise product development and accelerates product iteration, thereby promoting the product innovation of enterprises.

With regard to the research on digitization and enterprise process innovation performance, scholars have discovered that manufacturing enterprises can strengthen the automation of data acquisition and data processing by using digital technology. It can also optimize production processes and methods, thereby accelerating production process innovation and reducing the production cost of enterprises. For example, Herzog et al. [25] believed that the intelligent sensor technology to be integrated with production planning and control systems of enterprises can optimize the process flow of enterprises, bring high-quality production chains to enterprises, and reduce the production cost of enterprises. Hakanen and Rajala [26] found that IOT material intelligence with digital features can effectively track objects and items with specific attributes. This finding makes it possible to introduce artificial intelligence technology into enterprise production processes, and bring intelligent production lines to enterprises. Fu et al. [27] believe that digital transformation has prompted enterprises to actively adopt sensors and wireless technologies to trap all kinds of data in the production process. These production data will be uploaded to intelligent devices for analysis to guide production. Therefore, this will bring more advanced production processes to enterprises.

Regarding research on digitization and enterprise product innovation performance, scholars considered that digital technology mainly promotes information collection, information mining, information utilization, and information sharing in the product design departments of enterprises. This improves the output of enterprise product innovation and enables enterprises to obtain new benefit. For example, Anandhi [28] and Chen [24] believe that, through digital transformation, enterprise innovation activities are no longer restricted by geographical space. It improves the efficiency of technical information sharing of product design teams, which helps to promote enterprise product innovation performance. He et al. [29] pointed out that under the background of digital transformation, enterprises that introduce relevant digital technologies can fully tap into the needs of consumers, obtain more complete user portraits, and encourage enterprises to produce new products that are richer and more in line with user needs. Li et al. [30] and Charlie et al. [31] believe that digital technologies led by digital transformation can help product designers improve their knowledge acquisition ability, expand the breadth of knowledge acquisition, enhance the exploration knowledge association rate, and increase product innovation output. On account of the aforementioned viewpoints, this paper puts forward the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1a).

Digital transformation has a positive effect on the process innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises.

Hypothesis 1 (H1b).

Digital transformation has a positive effect on the product innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises.

2.2. Digital Transformation and R&D Capability

In order to achieve digital transformation, enterprises put some digital resources into the R&D process. Since digital technology has the characteristics of information mining, multi-dimensional transformation, and low cost, it has a great impact on the R&D capability of enterprises. When looking at the relevant research, enterprise R&D can be classified into exploratory R&D and exploitative R&D. Exploratory R&D generally includes developing new knowledge or replacing existing content in an enterprise’s R&D department [32,33,34], and usually requires enterprises to constantly learn new knowledge, carry out new experiments, develop new products, and design new marketing models [35]. Therefore, exploratory R&D often entails high risk, high input, low return, and low output in the short term, which is related to the high autonomy behavior and long-term input of enterprises [36]. On the flip side, exploitative R&D refers to further learning according to existing knowledge, that is, to utilize and redevelop existing knowledge [37,38]. In contrast to exploratory R&D, exploitative R&D requires enterprises to pay more attention to excavating the knowledge and capabilities that the current enterprise already have, and through this requirement, to improve their decision-making mechanisms so as to maximize their profits. Therefore, exploitative R&D is often accompanied by low risk, stable returns, better control, and higher efficiency, which can bring better results to enterprises in the short term [39].

The impact mechanism of enterprise digital transformation on two types of R&D is different. For exploratory R&D capability, scholars believe that digital technology can improve the ability of enterprises to explore new knowledge for creative R&D mainly through efficient knowledge acquisition, deeper knowledge interpretation, and multi-dimensional external knowledge transformation [22,40]. As for the exploitative R&D capability, digital technology mainly conducts incremental learning on existing knowledge by strengthening the internal refinement of knowledge. It also encourages enterprises to dig deeper into the internal relationship between knowledge, and greatly improve enterprises’ R&D capability based on existing knowledge in a short time [41]. Although digital transformation can promote two types of R&D capabilities in different ways, in the previous term of digital transformation, enterprises make different resource investments in the two types of R&D capabilities. Owing to the characteristics of great efficiency and low cost of exploitative activities, enterprise managers are more inclined to improve corporate profits through exploitative R&D capabilities. Robert [42] believes that in the previous term of enterprise digital transformation, enterprise managers have a tendency to use digital tools to improve enterprise performance in the short term. This tendency requires managers to promote the ability of exploitative R&D to achieve good digital transformation results in the short term. Similarly, Xiao [43] believes that learning existing knowledge and skills has the advantages of a short cycle and low cost, which helps enterprises to improve their R&D capabilities in the short term. At the moment, there are few digital suppliers with independent manufacturing capabilities in China. In the reality of high transformation costs, most manufacturing enterprises are still unable to afford huge digital transformation costs. Therefore, compared with the financial industry and retail industry, most manufacturing enterprises in China have a low level of digitalization and still remain in the previous term of digital transformation. Based on the above, this paper puts forward the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2 (H2a).

Digital transformation inhibits the exploratory R&D capability of manufacturing enterprises.

Hypothesis 2 (H2b).

Digital transformation promotes the exploitative R&D capability of manufacturing enterprises.

2.3. The Mediating Effect of R&D Capability

R&D capability is a key factor affecting enterprise innovation performance [44,45]. Based on the existing literature, it has been found that exploratory R&D capability and exploitative R&D capability have diverse influence on enterprise innovation performance. For one thing, from the perspective of limited resources, Levinthal and March [46] found that while enterprises put substantial resources into exploitative R&D to ensure the current competitive advantage, they also need to put more resources into exploratory R&D to ensure the future competitive advantage of enterprises. However, due to the constraints of resource allocation, it is difficult for enterprises to take into account both exploratory R&D and exploitative R&D. On the other hand, from the perspective of the interaction between two mechanisms, Kane [47] believes that the continuous learning of existing knowledge will lead to the homogenization of the knowledge in the R&D department of the enterprise, and this will lead to stagnation over time. Therefore, in the context of digital transformation, the effect of enterprise exploitative R&D capabilities on enterprise innovation performance is manifested in the improvement of short-term innovation results and the reduction of long-term innovation results. Although the impact of exploratory R&D capability on the innovation results of enterprises is not ideal in the short term, in the long run, the continuous introduction of fresh knowledge and internal transformation of enterprises is conducive to breaking the knowledge development stagnation zone of R&D using existing knowledge and to finally achieving the improvement of innovation results. It is obvious that exploratory R&D capability helps enterprises gain a competitive advantage in the long term, while exploitative R&D capability can stimulate enterprises to achieve peak performance in the short term. However, since enterprises cannot carry out only one form of R&D activity, how to balance exploratory R&D capability and exploitative R&D capability has become a common problem faced by enterprises in the early stages of digital transformation.

Smith and Lewis [48] found that in the process of enterprise digital transformation, the unbalanced growth of R&D capabilities led to the emergence of the digital paradox, which is manifested in the fact that the investment of enterprises in the field of digital technology has no positive impact on the growth of enterprise performance [49]. Specific to digital transformation and enterprise innovation performance, it has been shown that enterprise digital transformation will cause a drop in enterprise innovation performance instead of an increase [50]. Since the digital paradox was proposed, it has attracted extensive attention and follow-up research in the academic community. This paper proposes, on the one hand, in the early digital transformation, that enterprise managers will face the pressure of digital transformation. They are more inclined to adopt exploitative R&D to accelerate transformation, so they invest few resources in exploratory innovation. However, due to the long time frame and uncertainty involved in the transformation of exploratory R&D into enterprise innovation performance, it will lead to the failure of enterprises in improving their innovation performance through exploratory R&D in the short term. Therefore, the enterprises’ R&D tendencies avoid the high risk of exploratory R&D, which is beneficial to the improvement of enterprise innovation performance. On the other hand, due to the importance that enterprises attach to the exploitative R&D capability and its tendency to bring easier success in the short term, enterprises can improve their innovation performance through exploitative R&D in the short term. With the gradual deepening of the digital transformation, the results of exploitative R&D will stagnate. If enterprises do not immediately adjust the resource input of the two types of R&D, they will face the problem of the digital paradox. According to the above viewpoints, the following hypothesis are made:

Hypothesis 3 (H3a).

Exploratory R&D capability plays a mediating role in the process of digital transformation affecting the process innovation performance and product innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises.

Hypothesis 3 (H3b).

The mediating effect of exploratory R&D capability is embodied in that it will reduce two kinds of innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises.

Hypothesis 4 (H4a).

Exploitative R&D capability plays a mediating role in the process of digital transformation affecting the process innovation performance and product innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises.

Hypothesis 4 (H4b).

The mediating effect of exploitative R&D capability is embodied in that it will promote two innovation performances of manufacturing enterprises.

3. Research Design Variable Description

3.1. Model Design

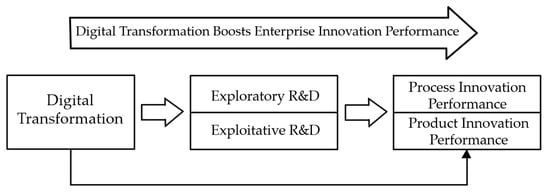

Based on the parallel mediation model of two mediating variables, this study mainly examines: (1) the direct impact of digital transformation on the process innovation performance and product innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises; (2) the direct impact of digital transformation on the exploratory and exploitative R&D capabilities of manufacturing enterprises; and (3) the mediating effect of exploratory R&D capability and exploitative R&D capability in the process of digital transformation influencing the process innovation performance and product innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises. Using the research methods of references Xie et al. [51] and Braun et al. [52], the theoretical model of this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

The corresponding regression equations are as follows:

- (1)

- The direct impact of digital transformation on process innovation performance and product innovation performance:

- (2)

- The direct impact of digital transformation on exploratory R&D capability and exploitative R&D capability:

- (3)

- The mediating effect of exploratory R&D capability and exploitative R&D capability:

Among them, “Explor”, “Exploi”, “Dig”, “Prod”, and “Proc”, respectively, represent the exploratory R&D capability, exploitative R&D capability, digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises, product innovation performance, and process innovation performance. zi indicates a round of control variables.

When conducting the mediation effect test based on the bootstrap sampling method, , respectively, represent the mediating effect of exploratory R&D capability, the mediating effect of exploitative R&D capability, and the total mediating effect of the two types of capabilities. , respectively, represent the direct effect of digital transformation on enterprise innovation performance and the total effect of digital transformation on enterprise innovation performance through intermediary variables. The parallel mediation effect test can be classified into three steps: the first step tests the significance of the coefficient when the mediating variable is used as the outcome variable; the second step uses the bootstrap method to test whether the individual mediating effect and the total mediating effect are significant; the third step uses the process macro developed by Hayes to test whether the total effect is significant.

3.2. Variable Description

- (1)

- Explanatory variable: Digital transformation degree of digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises. The annual report of an enterprise is an essential presentation of the enterprise’s development progress and strategic orientation. Therefore, this paper selects the frequency of keywords for digital transformation in annual reports of listed companies as the measurement index of this variable. Based on the research of Wu [53] and other scholars, the word frequency counting method identifies the keywords of the text of the annual report of enterprises from the 80 subdivision indicators in five aspects of artificial intelligence technology (artificial intelligence, machine learning, image understanding…), blockchain technology (digital currency, smart contracts, distributed computing…), cloud computing technology (memory computing, cloud computing, stream computing…), big data technology (big data, data mining, text mining…), and digital technology application (mobile internet, industrial internet, mobile payment…). Subsequently, the proxy indicators related to the digital transformation of enterprises are obtained by accumulating the word frequency of these keywords.

- (2)

- Intermediary variables: Exploratory R&D capability and exploitative R&D capability of manufacturing enterprises. Using Ning [54] for reference, this study selects the proportion of exploratory R&D patents and exploitative R&D patents in all patents of enterprises as the measurement indicators of the two types of R&D capabilities. According to the proposal of Sørensen and Stuart [55], Benner and Tushman [56], and Custodio et al. [57], whether a patent is an exploratory patent or an exploitative patent is mainly defined by the degree to which the patent uses existing knowledge or new knowledge. If more than 60% of the IPC4 classification numbers cited by a patent are different from the IPC4 classification numbers of existing company patents, it can be considered that the patent uses at least 60% of the new knowledge, and the patent is identified as an exploratory patent. If more than 60% of the IPC4 classification numbers cited by a patent are the same as the IPC4 classification numbers of existing company patents, it can be considered that the patent uses at least 60% of the existing knowledge, and the patent is considered to be an exploitative patent. Therefore, this study uses 60% of new knowledge as the critical value of exploratory R&D patents and exploitative R&D patents to obtain the measurement indicators of two types of R&D capabilities of each enterprise.

- (3)

- Explained variables. The explained variables in this study are the process innovation performance and product innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises. Considering that most scholars measure the innovation performance of enterprises by using the number of patent applications [58,59,60], this study selects the number of process innovation patents and product innovation patents of enterprises as the measurement indicators of the two types of innovation performance. Bena and Simintzi [61] proposed the measurement standard for enterprise process innovation patents and product innovation patents. Therefore, this paper mainly distinguishes process patents and product patents according to the patent name, which is based on the standardized language format used by enterprises when applying for patent names. For example, process innovation patents are usually described as “a method of…” or “a process of…”. In March 2013, Shenzhen Municipal Engineering Corporation of Shenzhen, China applied for a patent entitled “method for determination of coarse aggregate interstitial ratio”; in April 2019, Hunan Zhongke Shinzoom Technology Co., Ltd. of Changsha, China applied for a patent named “an elastic carbon material coating structure and coating process”. These are examples of typical process innovation patents. Compared with process innovation patents, the language formats used for the names of product innovation patents have the performance of variable language formats and a lower degree of standardization. Generally, on the basis of fixed language formats such as “a kind of … equipment” or “a kind of … device”, the name or attribute of the product will be directly used as the patent name. In October 2017, Shenzhen Municipal Engineering Corporation of Shenzhen, China applied for a patent named “a hammer-type gravel equipment”; in April 2021, Anhui Guoxing biochemistry Co., Ltd. of Maanshan, China applied for a patent entitled “a treatment device for acetaldehyde containing wastewater”; in March 2018, Shenzhen Skyworth Digital technology Co., Ltd. of Shenzhen, China applied for a patent named “a lighting control device and set-top box”, which are all typical examples of product innovation patents. Since process innovation patents are easier to judge than product innovation patents, this study first extracts the process innovation patents of Chinese manufacturing enterprises from the text information of Chinese invention and utility model patents, according to the method proposed by Bena and Molina [62]. After that, the remaining invention and utility model patents after extraction are taken as the product innovation patents of the enterprise.

- (4)

- Control variables. Referring to the practices of Chi et al. [63], the control variables chosen in this study include ownership concentration, chair–CEO duality, ownership type, debt–asset ratio, stock turnover ratio, audit opinion, and executive gender. The definitions of relevant variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Variable definitions.

Table 1. Variable definitions.

3.3. Data Source

This study selects A-share manufacturing enterprises in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets as the research samples to explore the impact of digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises on enterprise innovation performance. Referring to the description of the division of the development stages of China’s digital economy in the article “Review and Prospect of China’s Digital Economy Development” on people.com (accessed on 16 August 2018), which points out that after the quantity of mobile netizens in the whole society became large-scale in 2013, China’s digital economy has entered a new phase of rapid development. Therefore, this study selects 2013–2020 as the time interval of the research sample. The subdivided text indicators, enterprise patent text information, and various control variables of enterprise digital transformation come from the CSMAR database, and the two types of enterprise R&D capability indicators are mainly from the WinGo financial data platform. In terms of data screening, the collected index data were matched according to the securities code of listed companies and the year in which they are located. Then we eliminated the missing values of the sample data, and deleted the enterprise data with the total number of years less than four years, so as to achieve the purpose of data cleaning. Finally, 4009 enterprise-level data points were retained. The specific descriptive statistics are revealed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Results of Regression Analysis

In order to verify the relationship between digital transformation, the two types of R&D capabilities, and the innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises, this study examines the direct impact of digital transformation on the innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises, the direct impact of digital transformation on the two types of R&D capabilities of manufacturing enterprises, and the intermediary effect of the two types of R&D capabilities. The specific examination results are shown in Table 3. Among them, model (1) and model (2) use process innovation performance and product innovation performance as explained variables, mainly to test the direct impact of digital transformation on two types of innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises; model (3) and model (4) take the mediating variable exploratory R&D capability and exploitative R&D capability as the outcome variables to test the impact of digital transformation on the two types of R&D capability of manufacturing enterprises, which is the premise of the mediating effect test [51,52]; while model (5) and model (6) add mediating variables to the explanatory variables, and test the mediating effect of the two types of R&D capabilities with process innovation and product innovation as explained variables.

Table 3.

Results of the regression analysis.

The results show the following: (1) The digital transformation of enterprises has a positive effect on both process innovation performance and product innovation performance, indicating that the digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises will improve the two types of innovation performance of enterprises. Hypotheses H1a and H1b are thus verified. (2) The digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises has a negative effect on the exploratory R&D capability of manufacturing enterprises, which indicates that the digital transformation of Chinese manufacturing enterprises at this stage will reduce the exploratory R&D capability of enterprises. Upon further investigation, it was found that digital transformation has a positive impact on the exploitative R&D capability of enterprises, indicating that the digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises stimulates enterprises to develop their exploitative R&D capability. Hypotheses H2a and H2b are thus verified. (3) The digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises had a significant indigenous impact on both R&D capabilities of enterprises, so it meets the preconditions for the analysis of a parallel mediating effect. After adding the explanatory variable of digital transformation, we found that the exploratory R&D capability of enterprises has a negative impact on both process innovation performance and product innovation performance, which indicates that the impact of China’s manufacturing enterprises’ digital transformation strategy on enterprise innovation performance through exploratory R&D capability is still in the negative stage. (4) After adding the explanatory variable of digital transformation, it was found that an enterprise’s exploitative R&D capability positively affects the enterprise’s process innovation performance and product innovation performance, which indicates that the manufacturing enterprise’s digital transformation improves the enterprise’s process innovation performance and product innovation performance by developing the enterprise’s exploitative R&D capability.

4.2. Indirect Mediation Effect Test Based on the Bootstrap Sampling Method

This study adopted the bootstrap sampling method to test the indirect intermediary effect of exploratory R&D capability and exploitative R&D capability. The number of repeated samples was set to 5000 times. The analysis results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Test results of the mediating effect.

The results in Table 4 shows that the direct effect and total effect of digital transformation on the two types of innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises are positive. This result further proves that the digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises in China directly promotes the innovation performance of enterprises. In addition, the total effect of digital transformation on the two types of innovation performance of enterprises is greater than the direct effect, which manifests that the two types of R&D capabilities of enterprises do not have a masking effect on the path of the impact of digital transformation on the innovation performance of enterprises. Digital transformation has a positive indirect impact on enterprises through both types of R&D capabilities. The total indirect effects of the digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises on enterprise process innovation performance and product innovation performance are 0.0152 and 0.0103, respectively, and the upper and lower bounds of the bootstrap 95% confidence interval do not contain 0. Therefore, the original hypothesis that the total indirect effect is 0 is refused, manifesting that the total indirect effects of the two types of R&D capabilities as intermediary variables on enterprise innovation performance are significant. This study further examines the indirect mediating effect of exploratory R&D and exploitative R&D between the digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises and the two types of innovation performance of enterprises. The indirect effects of exploitative R&D capability on enterprise digital transformation in terms of enterprise process innovation performance and product innovation performance are 0.009 and 0.005, respectively, and the bootstrap 95% confidence interval does not include 0, indicating that the mediating effect of exploitative R&D capability on enterprise digital transformation, enterprise process innovation performance, and product innovation performance is significant. Therefore, hypotheses H3a and H3b are verified. Similarly, the indirect effects of exploratory R&D capability in terms of enterprise process innovation performance and product innovation performance are 0.023 and 0.02, respectively, and the bootstrap 95% confidence interval does not include 0, indicating that exploratory R&D capability plays a significant intermediary effect between enterprise digital transformation, enterprise process innovation performance, and product innovation performance. Therefore, hypotheses H4a and H4b are verified.

4.3. Sectoral Heterogeneity Analysis

In order to examine the sectoral discrepancies in the innovation performance of enterprises driven by digital transformation and the sectoral differences in the intermediary role of R&D capabilities, consulting the study of Chen et al. [64], the samples are divided into the textile manufacturing sector, the resource processing sector, and the machinery and equipment manufacturing sector, according to sectoral characteristics, to test the impact of sectoral characteristics on the innovation performance of enterprises assisted by digital transformation. Table 5 and Table 6 show the regression results. The upper part of the table reports the benchmark regression results, among which models (1)–(6) report the benchmark regression results of digital transformation on process innovation performance and product innovation performance in three sectors, and models (7)–(12) report Benchmark regression results after adding mediator variables. The lower part of the table shows the results of the mediation test of the two types of R&D capability.

Table 5.

Heterogeneity test of digital transformation on process innovation performance.

Table 6.

Heterogeneity test of digital transformation on product innovation performance.

According to the results of the benchmark regression, the digital transformation of the textile manufacturing sector has not had a positive effect on the innovation performance of enterprises. The digital transformation of the resource processing sector has effectively improved the process innovation performance of enterprises, but has not had an effect on the product innovation performance of enterprises. The digital transformation of machinery and equipment manufacturing enterprises has had a positive effect on the process innovation performance and product innovation performance of the enterprise in the meantime. This shows that there are sectoral discrepancies in the role of digital transformation in promoting the innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises. In general, the digital transformation of high-tech manufacturing has a more obvious role in promoting the innovation performance of enterprises. From the results of the mediation effect test, under the premise of satisfying the conditions for the analysis of the parallel mediation effect, the indirect effects of enterprise digital transformation on the process innovation performance and product innovation performance of enterprises through exploratory R&D capabilities and exploitative R&D capabilities are both positive, and the bootstrap confidence interval does not contain zero. Therefore, for enterprises where digital transformation can play an effective role, there is no sectoral discrepancies in the direction in which digital transformation affects the innovation performance of enterprises through the mediating variable of R&D capability. However, the direct effect and total effect of the digital transformation of machinery and equipment manufacturing enterprises on the innovation performance of enterprises are greater than those of textile manufacturing enterprises and resource processing enterprises. Therefore, it can be inferred that the digital transformation of high-tech manufacturing sectors plays a greater role in promotion of the innovation performance of these enterprises, and that the digital transformation of high-tech manufacturing enterprises directly improve their product output. The effect of optimizing the production process is more obvious.

4.4. Robustness Test

Firstly, this study removes outliers that may affect the results, and then re-estimates the results. Then, we consider re-estimating the maximum and minimum values of digital transformation and the two types of innovation performance. Second, drawing on the method of Song, since the digital transformation degree of the information and communication industry is significantly higher than that of other manufacturing industries, excluding the computer communication and other electronic manufacturing industries, the results of the two types of robustness test methods are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Robustness test for eliminating outliers.

The regression results show that after removing outliers, the result that digital transformation affects the innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises through R&D capabilities is still significant, which manifests that the model and regression results in this study are robust and that the conclusions revealed by the regression results are highly persuasive and reliable. However, the model may also have endogeneity, which may lead to “pseudo regression” and other problems. Therefore, this study selects the digital transformation with a lag of one phase as an instrumental variable to carry out a two-stage least squares regression (2SLS). The following Table 8 shows the regression results. The results show that the instrumental variables do not have weak tools and over-identification problems, and the instrumental variable regression results are in good agreement with the benchmark regression results, further indicating that the regression model and results in this paper have high robustness.

Table 8.

Robustness test of the instrumental variable method.

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Results of Regression Analysis

Using the data of A-share listed manufacturing enterprises in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 2013 to 2020, this paper investigates the relationship between digital transformation and the R&D capability and innovation performance of manufacturing enterprises, and draws the following conclusions:

The digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises directly improves the process innovation performance and product innovation performance of enterprises. For one thing, digital transformation promotes the modularization, automation, and intelligence of the production process in the production department of enterprises, and brings high-efficiency production processes and methods to the production department of the enterprises [65]. For another thing, digital transformation promotes the flow of information in the product design department, expands the breadth of information sources, and expands the depth of information mining so as to stimulate the creativity of new product development of enterprises [24,66]. This paper provides empirical evidence for the positive impact of digital transformation on the process innovation performance and product innovation of manufacturing enterprises, which means that the deep integration of digital technology and enterprise manufacturing will accelerate enterprises’ innovative production processes and improve the output of innovative products.

The digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises inhibits the exploratory R&D capability of enterprises and promotes the exploitative R&D capability of enterprises. In the process of digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises, the introduction of digital technology is conducive to improving the efficiency of internal transformation of the external knowledge obtained by enterprises. It also helps enterprises with the in-depth refining of internal stock knowledge [22,40,41]. However, from the empirical results of this paper, it can be concluded that manufacturing enterprises prefer to adopt digital technology to improve the exploitative R&D capability. This shows that the managers of manufacturing enterprises in China are more inclined to adopt the decision-making direction of digital transformation to promote the exploitative R&D capability.

Exploratory R&D capabilities and exploitative R&D capabilities play an intermediary role in the process of digital transformation affecting enterprise process innovation performance. This role is embodied in that digital transformation promotes the performance of enterprise process innovation through both exploratory R&D and exploitative R&D. Although the results of the mediating effects of the two types of R&D capabilities on process innovation performance are consistent, the mechanisms of the two are different. This paper believes that the current management of China’s manufacturing enterprises are generally facing the pressure of digital transformation. This makes enterprises focus on the development of exploitative R&D capabilities that can bring more benefit to enterprises in the short term [42], which will lead to a decline in input in exploratory R&D activities. For one thing, the digital transformation strengthens the production department’s in-depth excavation of the existing production processes and methods of the enterprise, and encourages the enterprise to gain more exploitative R&D activities to stimulate the enterprise to obtain more process innovative results in the short term. For another thing, due to the high-risk and short-term low-return nature of exploratory R&D, the pressure of digital transformation actually helps enterprises avoid the risk of exploratory R&D, which makes a positive contribution to the process innovation performance of enterprises from another perspective.

Exploratory R&D capability and exploitative R&D capability also play an intermediary role in the process of digital transformation affecting the product innovation performance of enterprises. Since the direction of empirical results of this intermediary role is the same as that of process innovation performance, this paper argues that the digital transformation of enterprises impacts on the production department and product design department of enterprises by changing their exploitative R&D capabilities, while exploratory R&D capabilities remain consistent.

The above conclusions are discussed from the perspective of direct effect and indirect effect, respectively. Further comparing the two, this paper finds that the total indirect effect of digital transformation on the two types of innovation performance of enterprises through enterprise R&D is much smaller than the direct effect of digital transformation on the two types of innovation performance of enterprises. This indicates that digital transformation mainly directly affects the production department and product design department of enterprises. The digital transformation of Chinese manufacturing enterprises is still insufficient to drive enterprise innovation by innovating the R&D capabilities of enterprise R&D departments.

The impact of digital transformation of manufacturing enterprises on enterprise innovation performance has sectoral differences. The difference is embodied by the fact that the digital transformation of the machinery and equipment manufacturing sector will promote both process innovation performance and product innovation performance; the digital transformation of the resource processing sector can only promote process innovation performance, but has no impact on product innovation performance; while the digital transformation of the light textile manufacturing sector had no impact on both process innovation performance and product innovation performance. Generally speaking, with the increase of manufacturing technology complexity, the driving effect of digital transformation on enterprise innovation performance is more obvious. However, there is no sectoral difference in R&D capability in the development of digital transformation-driven enterprise innovation performance. This paper provides empirical evidence for the heterogeneity of digital transformation affecting innovation performance and the homogeneity of the mediating role of R&D capabilities. This means that enterprises with more complex manufacturing technology often have higher requirements for capital, talents, and enterprise scale [67]. Therefore, manufacturing enterprises with higher technical content can better bear the risk of failure of digital transformation by virtue of strong capital and talent advantages [68], and can invest more in digital transformation. At the same time, the more complex the manufacturing technology means the more complex the production process, the more diversified the products, and the faster the iteration speed [69]. Therefore, the effect of digital transformation on enterprise innovation performance is transmitted faster and the effect is further amplified. On the contrary, enterprises with low technical content tend to have low profit and cannot afford the high cost of digital transformation due to the low added value of products. Therefore, the digital transformation of such enterprises is slow [70,71]. At the same time, manufacturing enterprises with low technical content tend to have simple production processes and single products. The effect of digital transformation on innovation performance is less obvious than that of high-tech manufacturing enterprises.

5.2. Management Implications and Policy Recommendations

In the era of the digital economy, digital transformation has gradually become the key engine of enterprise R&D and innovation. How to use digital transformation to empower enterprises to innovate and gain competitive advantages is becoming an important issue for enterprises. The research conclusions of this paper provide four implications for the management practice and policy support of manufacturing enterprises in China:

- (1)

- Manufacturing enterprises should continue to promote the digital transformation strategy. On the one hand, enterprises should focus on the in-depth integration of digital technology and enterprise manufacturing, especially processes and techniques. Enterprises can use digital technology to collect production data in real time, and strengthen data analysis and value mining. They can also rely on digital technology to achieve accurate demand prediction, equipment remote monitoring, energy consumption management, and finely manage production processes. On the other hand, enterprises should increase the construction and investment of the digital platform. Enterprises should further construct digital platforms on the basis of the current informatization construction achievements, and introduce emerging digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, big data, and cloud computing to upgrade enterprise information systems. Improving the efficiency of enterprise information collection, information mining, and information sharing will be conducive to the output of new products.

- (2)

- R&D is the source of enterprises innovation. Chinese manufacturing enterprises should accelerate the deep integration of digital technology and the R&D department, reform and enlarge the R&D capability of enterprises through digital transformation, and adjust the R&D mode of the R&D department to make it more compatible with the digital transformation strategy. This paper suggests that the digital transformation of China’s manufacturing enterprises at this stage should concentrate on improving the exploitative R&D capability of enterprises. Enterprises need to know the advantages and disadvantages of their production processes, the market positioning of the products they produce, and their current growth stage. Although digital technology can accelerate the transformation and upgrading of manufacturing enterprises, it cannot be denied that the cost of digital transformation is expensive. Enterprises should fully utilize the existing digital infrastructure and steadily advance through exploitative R&D on the basis of the current level of enterprise digitalization.

- (3)

- Enterprises should aim for balanced investment in R&D to avoid sinking into the digital paradox. Practical experience shows that the digital transformation of enterprises is a long-term and onerous task, and failures in the transformation process are inevitable [70,71]. Therefore, while taking the improvement of exploitative R&D capability as the key focus in the initial stage of digital transformation, manufacturing enterprises should also focus on continuously accumulating experience in the practice of exploratory R&D activities. Enterprises should use digital technology to expand their R&D advantages in basic research and industrial generic technology, and help enterprises achieve technological breakthroughs in key areas. This not only establishes a long-term competitive advantage for enterprises, but also makes an important contribution to China’s in-depth implementation of innovation-driven development strategy.

- (4)

- The government should formulate differentiated policies that are suitable for different types of manufacturing enterprises to carry out digital transformation. The empirical results of this paper show that high-tech manufacturing enterprises have the ability to carry out digital transformation independently, and such enterprises are often the biggest beneficiaries of digital transformation. Therefore, such enterprises should be mainly subsidized secretly, that is, the government needs to issue more precise policies to guide them to further deepen the digital transformation and avoid the waste of enterprise resources. On the other hand, for enterprises with low technology content, the road to digital transformation is often more difficult. Therefore, for such enterprises, both explicit and implicit subsidies should be applied. The government not only needs to give them more powerful and looser policy support, but also needs to directly grant special subsidies for digital transformation to enterprises that meet the conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.; methodology, S.L. and T.L.; software and formal analysis, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L. and T.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L.; visualization, S.L. and T.L.; supervision and funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data and estimation commands that support the findings of this paper are available upon request from the first and corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 13–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.Y.; Wu, Z.; Yang, F. Research on the Relationship between Digital Transformation and Performance of SMEs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.M.; Ye, D.L.; Wang, J.J.; Zhai, S.S. How Can Chinese Small- and Medium-sized Manufacturing Enterprises Improve the New Product Development (NPD) Performance? From the Perspective of Digital Empowerment. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2020, 23, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.Y.; Oh, K.S.; Wang, M.M. Strategic Orientation, Digital Capabilities, and New Product Development in Emerging Market Firms: The Moderating Role of Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.S.R.; Wäger, M. Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Plan. 2018, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.C.; Yan, J.C.; Zhang, S.X.; Lin, H.C. Can Corporate Digital Transformation Promote Input-Output Efficiency? Manag. World 2021, 37, 170–190. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, J.L.; Sawaya, W.J. Tortoise, not the hare: Digital transformation of supply chain business processes. Bus Horiz. 2019, 62, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennelly, P.A.; Srai, J.S.; Graham, G.; Wamba, S.F. Rethinking supply chains in the age of digitalization. Prod. Plan. Control 2020, 31, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gu, X. Equilibrium Analysis of Manufacturers’ Digital Transformation Strategy under Supply Chain Competition. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, V.W.; Tian, X.; Tice, S. Does stock liquidity enhance or impede firm innovation? J. Financ. 2014, 69, 2085–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norli, Ø.; Ostergaard, C.; Schindele, I. Liquidity and shareholder activism. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2015, 28, 486–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, S.; Lukose, P.J.J.; Komera, S. Financing constraints and investments in R&D: Evidence from Indian manufacturing firms. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2015, 55, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, J.; Matias, J.C.O. Open innovation 4.0 as an enhancer of sustainable innovation ecosystems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, M.; Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Maksimovic, V. Firm Innovation in Emerging Markets: The Role of Finance, Governance, and Competition. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2011, 46, 1545–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.A.; Vieito, J.P. CEO gender and firm performance. J. Econ. Bus. 2013, 67, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnitzki, D.; Kraft, K. Capital control, debt financing and innovative activity. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2009, 71, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Hofman, P.S.; Newman, A. Ownership concentration and product innovation in Chinese private SMEs. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2013, 30, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. The construction of the appraising index system of innovative firm on the basis of technical innovation audit theory. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2007, 25 (Suppl. S2), 465–469. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Chen, Y. The Study of Indictors System on Technological Innovation Performance in Enterprises. Sci. Sci. Manag. Sci. Technol. 2006, 3, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Fan, M.; Zhang, H. Information technology and organizational capabilities: A longitudinal study of the apparel industry. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.J.M.; Fernandes, C.I.; Ferreira, F.A.F. To be or not to be digital, that is the question: Firm innovation and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, T.J.; Meyer, M.H.; Barczak, G. The influence of digital design and IT on modular product architecture. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Nevo, S.; Jin, J.; Tang, G.; Chow, V.W.S. IT capabilities and innovation performance: The mediating role of market orientation. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2013, 33, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Nevo, S.; Benitez-Amando, J.; Kou, G. IT capabilities and product innovation performance: The roles of corporate entrepreneurship and competitive intensity. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, K.; Winter, G.; Kurka, G.; Ankermann, K.; Binder, R.; Ringhofer, M.; Maierhofer, A.; Flick, A. The Digitalization of Steel Production. Berg-Huettenmaenn. Monatsh. 2017, 162, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, E.; Rajala, R. Material intelligence as a driver for value creation in IoT-enabled business ecosystems. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2018, 33, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Xu, Q.; Lin, S. Business Process Digitization, Organizational Inertia and Innovation Performance in Incumbent Firms. R&D Manag. 2021, 33, 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj, A.S. A Resource-Based Perspective on Information Technology Capability and Firm Performance: An Empirical Investigation. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 169–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Fang, X.; Liu, H.Y.; Li, X.D. Mobile app recommendation: An involvement-enhanced approach. MIS Q. 2019, 43, 827–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X.L.; Zhao, W. Design creativity in product innovation. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2007, 33, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.L.; Kim, H.H.M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Special Issue: Data-Driven Design. J. Mech. Des. 2017, 139, 110301. [Google Scholar]

- Abernathy, W. The Productivity Dilemma; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- March, J.G. Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentland, B.T. Information systems and organizational learning: The social epistemology of organizational knowledge systems. Inf. Organ. 1995, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Du, K.; Byun, G.; Zhu, X. Ambidexterity in new ventures: The impact of new product development alliances and transactive memory systems. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 75, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.S.; Crespo, Á.H.; Agudo, J.C. Effect of market orientation, network capability and entrepreneurial orientation on international performance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, R.; Bengtsson, L.; Henriksson, K.; Sparks, J. The Interorganizational Learning Dilemma: Collective Knowledge Development in Strategic Alliances. Organ. Sci. 1998, 9, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D.; Zeithaml, C. Garbage Cans and Advancing Hypercompetition: The Creation and Exploitation of New Capabilities and Strategic Flexibility in Two Regional Bell Operating Companies. Organ. Sci. 1996, 7, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenamor, J.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. How entrepreneurial SMEs compete through digital platforms: The roles of digital platform capability, network capability and ambidexterity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.Q.; Yang, C.H. Information technology and organizational learning in knowledge alliances and networks: Evidence from U.S. pharmaceutical industry. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.H.; Wang, P.C.; Yang, M. Digital empowerment promotes mass customization technology innovation. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2018, 36, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, R.W.; Keil, M.; Muntermann, J.; Mähring, M. Paradoxes and the Nature of Ambidexterity in IT Transformation Programs. Inf. Syst. Res. 2015, 26, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.H.; Wu, X.L.; Xie, K.; Wu, Y. IT-Driven Transformation of Chinese Manufacturing: A Longitudinal Case Study on Leap-Forward Strategic Change of Midea Intelligent Manufacturing. Manag. World 2021, 37, 161–179. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.W.; Lee, Y.K.; Hung, S.C. R&D intensity and commercialization orientation effects on financial performance. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 679–685. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, R.; Nesta, L. Product Innovation and Survival in a High-Tech Industry. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2009, 34, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinthal, D.A.; March, J.G. The Myopia of Learning. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G.C.; Alavi, M. Information Technology and Organizational Learning: An Investigation of Exploration and Exploitation Processes. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Lewis, M.W. Toward A Theory of Paradox: A Dynamic Equilibrium model of Organizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 381–403. [Google Scholar]

- Matt, C.; Hess, T.; Benlian, A. Digital Transformation Strategies. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2015, 57, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.F.; Cao, J.Y.; Du, H.Y. Digitalization Paradox: Double-Edged Sword Effect of Enterprise Digitalization on Innovation Performance. R&D Manag. 2022, 34, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Han, Y.; Anderson, A.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S. Digital platforms and SMEs’ business model innovation: Exploring the mediating mechanisms of capability reconfiguration. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2022, 65, 102513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.; Peus, C.; Weisweiler, S.; Frey, D. Transformational leadership, job satisfaction, and team performance: A multilevel mediation model of trust. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Hu, H.Z.; Lin, H.Y.; Ren, X.Y. Enterprise Digital Transformation and Capital Market Performance: Empirical Evidence from Stock Liquidity. Manag. World 2021, 37, 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, N.; Tian, X. Accessibility and materialization of firm innovation. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 48, 515–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, J.B.; Stuart, T.E. Aging, obsolescence, and organizational innovation. Admin. Sci. Q. 2000, 45, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, M.J.; Tushman, M.L. Exploitation, exploration, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custódio, C.; Ferreira, M.A.; Matos, P. Do General Managerial Skills Spur Innovation? Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, W.D.; Chandy, R.; Dorotic, M. Consumer cocreation in new product development. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwa, L.E.; Yeon, K.C.; Wook, Y.J. Relationship between User Innovation Activities and Market Performance: Moderated Mediating Effect of Absorptive Capacity and CEO’s Shareholding on Innovation Performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10532. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, A.H.; Zhang, Z.B.; Zhang, H. Impact of state-owned enterprise mixed ownership reform on innovation performance. Sci. Res. Manag. 2021, 42, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bena, J.; Simintzi, E. Machines Could Not Compete with Chinese Labor: Evidence from US Firms’ Innovation; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2613248 (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Bena, J.; Ortiz-Molina, H.; Simintzi, E. Shielding firm value: Employment protection and process innovation. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, in press. [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.M.; Wang, J.J.; Wang, W.J. Research on the influencing mechanism of firms’ innovation performance in the context of digital transformation: A mixed method study. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2022, 40, 319–331. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Cai, Y.Z. The Impact of Digital Technology on the Growth Rate and Quality of China’s Manufacturing Industry: An Empirical Analysis Based on Patent Application Classification and Industry Heterogeneity. Rev. Ind. Econ. 2021, 6, 46–67. [Google Scholar]

- Seethamraju, R.; Seethamraju, J. Enterprise systems and business process agility-a case study. In Proceedings of the 2009 42nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Big Island, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2009; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kache, F.; Seuring, S. Challenges and opportunities of digital information at the intersection of Big Data Analytics and supply chain management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Man. 2017, 37, 10–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Chao, C.A. Growth and evolution of high-technology business incubation in China. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2011, 30, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Lyytinen, K.; Majchrzak, A.; Song, M. Digital innovation management: Reinventing innovation management research in a digital world. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriole, S.J. Five Myths about Digital Transformation. MIT Sloan. Manag. Rev. 2017, 58. Available online: http://mitsmr.com/2ki2h8A (accessed on 6 February 2017).

- Bughin, J. The best response to digital disruption. MIT Sloan. Manag. Rev. 2017, 58, 58479. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Chen, G. Research on the Spatial Effect of Digital Transformation on Industrial Structure Upgrade—Empirical Analysis Based on Static and Dynamic Spatial Panel Models. Res. Econ. Manag. 2021, 42, 30–51. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).