Abstract

International students enrolled in the long term are considered habitual residents. They act as hosts to their friends and relatives, generating word-of-mouth recommendations and revisiting the host country. In order to facilitate inbound tourism in post-COVID-19 tourism, it is necessary to understand their risk perception, place image, and loyalty and provide meaningful insights for tourism markets. This study explores how social and personal risk perception of COVID-19 and cognitive and affective place image explain place loyalty. International students for degree programs comprised the sample population for this study. Findings revealed that social risk perception negatively shapes cognitive and affective place image, while personal risk perception only explains affective place image. Both cognitive and affective place image significantly affects place loyalty and mediates between social risk perception and place loyalty. The research provides new evidence on the risk perception of COVID-19, showing that internal factors such as social and personal risk perception may cause somewhat different results contrary to previous studies. Although gender moderates the relationship between cognitive place image and loyalty, the influence of gender on the theoretical and empirical relationships between risk perception, place image, and loyalty is not significant for international students. Implications for theory and practice, limitations, and future studies are discussed.

1. Introduction

At the heart of tourism is the interaction between people and places [1]. However, due to the unprecedented downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly everything in the tourism industry, from traveling rules and regulations to past tourism habits, has been dramatically altered [1]. Such fundamental conditions have created opportunities for many countries and places to reevaluate and readjust to suit the changing international tourism landscape [2].

South Korea (hereafter Korea) became a major tourism hotspot receiving approximately 30 million visitors in 2019, pushed by the global popularity of the Korean wave described as K-drama and K-pop [3]. However, faced by the global tourism industry during the pandemic, Korea has seen a sharp decline in inbound international tourists to the most frequent destination [4]. In this respect, the tourism industry should prepare for the next wave of international tourists when travel is safe and restrictive [5].

Despite the decrease in the number of international visitors entering Korea, the number of long-term international students who aim to achieve degrees is increasing. According to the Ministry of Education [6], the number of international visitors entering Korea to study abroad decreased by nearly 80% before the outbreak of COVID-19. However, the number of international students pursuing degree programs increased by around 6%.

Such growth indicates a potential opportunity for local universities and the tourism market, as a population of international students can be considered inbound tourists and attract international visitors from their home country [7]. In the tourism context, international students, especially long-term students who are pursuing degrees, are considered important for tourism because the travel pattern of international students is similar to long-term tourists who travel for a more extended period [8]. Furthermore, they are likely to generate positive word of mouth and recommendations [9] and act as hosts and guides to family or friends visiting them from their home country [10]. Consequently, international students can significantly aid destination recovery by restoring trust and confidence-building for international travelers in post-COVID-19 global tourism [11].

Place image in tourism research has typically focused on tourists as the core unit of analysis, examining the images conceived by tourists [12]. Although tourist destination image was strongly emphasized in the past, there is a growing recognition of residents’ place, which is equally pivotal to tourism development and marketing [13]. Because the place image indicates residents’ general impressions of the place, such beliefs can act as variables specific to tourism support [14]. Therefore, place image from the resident perspective should be explored to understand its impact on perceptions of tourism for its development with residents’ word of mouth intentions [15]. Residents perceive their image of the place they reside in as more complex and comprehensive than visitors [14], and previous studies confirmed that the two parties showed differences in the images of the place [16]. In response to this lack of empirical research in this field, the study applies risk perception and place image to examine how international students, specific to long-term period, support for positive word of mouth and revisit intention are shaped, as discussed below.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Role of International Students in Tourism

International students are defined as foreign students who cross borders to another country intending to study. Their main goal is to pursue their studies, yet they often travel to host countries to deepen their socio-cultural understanding and facilitate adaptation to the host country’s cultures [17]. They are likely to have ample chance to reflect on tourists’ subjective, individual moments in a host country [18].

In terms of global student mobility, around 4.3 million higher education students are being educated outside their home countries, which is expected to double by 2025 [19]. The number of international students studying in Korea has been rapidly growing, representing over 100,000 as of June 2016, more than an eightfold increase from 2003. The Korean government has deliberated on measures to increase the number of international students coming to Korea up to 200,000 in 2023, expanding the number of international students by more than 5% until 2023 [9]. Although Korea saw expansion in the volume of population mobility over the past few decades, the international flow was sharply reduced due to the outbreak of COVID-19 [20]. With such a rapid decline projected, travel restriction has unpredictably influenced the flow of travelers in Korea. The COVID-19 pandemic has dealt a severe blow to Korea regarding international student mobility.

UNWTO suggests that international students who study abroad for a short period are considered tourists, whereas those who enroll in the long term should be considered habitual residents. Although both types of students have a similar ability to receive visitors and attract tourism demand for a region [7], the growing number of international students, specifically long-term period students, is a critical component in analyzing the perception of international sojourners residing in Korea and rescuing tourism destination under COVID-19 crisis.

Tourism researchers have noted that international students may create a long-term economic impact on the tourism industry, a significant amount of potential to influence and attract future visitors to their host destination [8], and economic contribution to destination areas [21]. Furthermore, previous research focused on the visiting friends and relatives (VRF) tourism aspect of international students’ behavior emphasizes their role as hosts for visits [10]. International students not only act as hosts to their friends and relatives visiting them from their home country but also generate word-of-mouth recommendations and revisit the host country [22].

Another notable aspect of tourism and education experience is a settlement in a host country. Because such experiences can make a place appealing from their point of view, VRF tourism could be a starting point for future long-term migration since it strongly connects with decisions concerning community settlement processes, migration trends, and family attachment [23]. Further, the Korean government announced its aim to strengthen support for foreigners in the field of technology and culture through immigration policies and to lay the foundation for policy to accommodate international students as immigrants [24].

Despite the importance of international student research to the literature, the previous literature has mainly focused on how to support international students, encouraging them to become positive influencers for receiving more prospective students [3]. However, considering the recent mobility and policy trend of international students in Korea, it would be worthwhile to note international students from a residence perspective to create a safeguarding place image under the post-COVID-19 crisis.

2.2. Components of Risk Perception

Risk perception is the subjective evaluation of a threatening situation based on its features, the severity of hazards that people might be exposed to, an individual’s perspective, and the likelihood of negative consequences of a choice [25]. The evaluation of risks can influence an individual’s behavior affected by numerous individual and societal factors and different social factors [26]. Consequently, perceived risks can differ in people with the same outcome [27].

In tourism, risk perception is related to evaluating a particular situation concerning the risk of making an intention to travel and purchase [28] and uncertainty in travel decision-making [29]. Quintal et al. [27] classified perceived risk into six categories: financial, performance, physical, psychological, social, and convenience loss. This result aligns with Heung et al. [30] study that internal and external factors shape tourist risk perception. Internal factors are related to tourists themselves, referring to the factors that determine the perception of the informed risks. The external factors are related to information sources, including media and destination image, providing tourists with actual risk information. Tyler and Cook [31] suggested two components of risk perception, personal risk perception, and social risk perception. Personal risk perception refers to an opportunity for loss or damage that individuals feel for themselves, whereas social risk perception is considered an estimate of the general level of loss or damage to society [32]. The following hypotheses are derived from the previous literature:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Social risk perception of COVID-19 has a significant effect on cognitive place image.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Social risk perception of COVID-19 has a significant effect on affective place image.

Previous research has verified that the level of risk perception toward COVID-19 is strongly related to individual factors. Demographic characteristics are considered critical consequences of the level of risk perception [33], and these findings also agree with prior studies conducted by Neuburger and Egger [34]. They argued that significant age, travel frequency, and gender differences result in different travel risk perceptions and travel behavior. Yang and Nair [35] categorized 15 internal factors into four dimensions, socio-cultural, socio-demographic, psychographic, and biological. Nationality and experience contained in socio-cultural and socio-demographic, respectively, were the most significant factors influencing how tourists perceive risks.

People may underestimate their own risk of infecting with the virus. The prevalent finding of many people’s belief that they are less likely to be affected by a personal risk compared with the community has been considered an optimistic bias [36,37]. The optimistic bias is in line with the third person effect, in which Davison [38] suggested that people tend to perceive that the media have a more significant effect on others than on us, in that they are less likely influenced than others. The following hypotheses are derived from the previous literature:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Personal risk perception of COVID-19 has a significant effect on cognitive place image.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Personal risk perception of COVID-19 has a significant effect on affective place image.

2.3. Place Image and Place Loyalty

Image is defined as our subjective knowledge we believe to be true [39]. Place image refers to the perspectives people hold of a place [40] or the sum of individuals’ beliefs, ideas, and impressions of a place [41]. People’s subjective knowledge consists of images of facts and values; thus, place image comprises cognitive and affective components [42]. The components shape behavior intentions, encompassing people’s beliefs and knowledge regarding a destination and corresponding to their feelings and emotions, respectively [43]. In tourism, place image research has commonly studied the notion of tourism destination image, affecting tourists’ choice, experience, and behavior related to tourist places [44,45]. Although destination image has been strongly emphasized in the past, the place image represents residents’ general impressions of the place, which could act as pivotal in tourism planning, development, and marketing [13].

Unlike tourists, residents are inclined to have a complex and comprehensive interpretation of their place [14], and the two parties’ images are different in that the place serves as more than a holiday destination [46]. Residents serve as destination marketers by recommending attractions, facilities, cultural sites, and activities to visiting tourists, friends, and relatives due to familiarity with their place [22,47]. Therefore, residents’ place image is a crucial determinant of perceived tourism impacts and behavioral intentions. Despite the notable contributions of residents, current knowledge concerning the place image of a tourist destination remains scarce. Thus, the place image studies should be explored to capture the residents’ perspectives [14]. The place image has been classified into cognitive and affective images [48,49]. The cognitive image denotes an evaluation of the perceived attributes based on personal knowledge and beliefs of the place, whereas the affective image is related to people’s emotional responses and feelings towards the place [50,51]. The following hypotheses are derived from the previous literature:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Affective place image has a significant effect on cognitive place image.

The prior study of Zhang et al. [52] on the relationship between place image and loyalty concluded that cognitive and affective images positively affect loyalty. Further on such results regarding the two distinct forms of image, Almida-Santana and Moreno-Gil [53] found that affective image significantly affects place loyalty, and Stylidis [51] suggests that affective image seemed to be more powerful in predicting loyalty than the cognitive image within the high loyal group.

Loyalty is commonly defined as the preference of visitors to participate in a specific recreational activity [54]. In the tourism literature, loyalty refers to visitors’ perceptions of a place as recommendable, degree of revisit intention, and positive word of mouth to family and friends [55,56]. Place loyalty is considered an important indicator of successful place development for tourists’ destinations [45]. Previous studies reported that the antecedents of tourists’ loyalty refer to place image, perceived value, and satisfaction [57,58]. In addition, tourists are more likely to visit the place and recommend it to others when people have a favorable image of the place [44]. The construct of loyalty can be a composite concept that incorporates some interrelated components of behavioral, attitudinal, and composite [59]. The following hypotheses are derived from the previous literature:

Hypothesis 4a (H4a).

Cognitive place image mediates the social risk perception of COVID-19 and place loyalty.

Hypothesis 4b (H4b).

Cognitive place image mediates the personal risk perception of COVID-19 and place loyalty.

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

Affective place image mediates the social risk perception of COVID-19 and place loyalty.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

Affective place image mediates the personal risk perception of COVID-19 and place loyalty.

Behavioral loyalty is operationalized as re-patronizing to the destination. Attitudinal loyalty implies a tourist’s predisposition toward a tourist destination already visited, declaring an intention to a recommendation to others. Composite loyalty integrates behavioral and attitudinal aspects of loyalty [60]. Based on the prior studies, intention to revisit and positive word-of-mouth effects on friends and relatives have remained an adequate measurement for place loyalty [45]. Therefore, the same measurement was used in this study. The following hypotheses are derived from the previous literature:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

The cognitive image has a significant effect on place loyalty.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

The affective image has a significant effect on place loyalty.

2.4. Gender As a Moderating Variable

Gender is shared by all individuals of a community, described as a system of social beliefs and practices that discriminate men from women [61]. Not only is it biologically determined, but gender is also socially and culturally constructed [62]; thus, individuals react differently to the same situation depending upon their gender [63]. Because gender is embedded in all aspects of society, gender differences can be seen clearly in behavior intention in tourism [64]. Although gender is considered an important variable, gender differences research has been neglected [65].

Gender differences can be affected by the perception of various risks. Yang et al. [66] suggested that men and women may be sensitive to different risks and perceive the same risks differently. For example, men express less concern for various risks than women; men are riskier tolerant. Concerning travel experiences, previous researchers reported that female tourists are more sensitive to physical risks [67] and an extra discomfort traveling alone [68].

According to Wang et al. [69], women showed higher ratings about China’s national image than men in the wake of COVID-19. The empirical results showed that the relationship between perceived risk and place image is differentiated by gender. Carballo et al. [70] suggested that the sensitivity of the place image to the risk perception of tourists is higher for the male group since men showed a higher risk perception of place image than women. Furthermore, the negative influence of higher risk perception of a place on its image decreases in visit intentions showed higher for women than men. The following hypotheses are derived from the previous literature:

Hypothesis 8a (H8a).

Gender significantly moderates the relationship between the social risk perception of COVID-19 and cognitive place image.

Hypothesis 8b (H8b).

Gender significantly moderates the relationship between the social risk perception of COVID-19 and affective place image.

Hypothesis 8c (H8c).

Gender significantly moderates the relationship between the personal risk perception of COVID-19 and cognitive place image.

Hypothesis 8d (H8d).

Gender significantly moderates the relationship between the personal risk perception of COVID-19 and affective place image.

In the tourism context, gender moderates the relationships between behavior constructs [71], affective image and tourist expectations, and quality and behavior loyalty [72]. Research also showed that gender differences could be found in perceived place images. Based on the prior studies, it should be considered that gendered risk perceptions may also function to place image and tourists’ behavior intentions [1]. The following hypotheses are derived from the previous literature:

Hypothesis 8e (H8e).

Gender significantly moderates the relationship between cognitive place image and affective place image.

Hypothesis 8f (H8f).

Gender significantly moderates the relationship between cognitive place image and place loyalty.

Hypothesis 8g (H8g).

Gender significantly moderates the relationship between affective place image and place loyalty.

3. Research Method

3.1. Research Instrument

Based on the hypotheses generated in the prior section, a conceptual research model with social and personal risk perception of COVID-19 as the independent variable and place loyalty as the dependent variable is presented in Figure 1. This research model consists of seven direct influence hypotheses, four mediating and seven moderating hypotheses. This research aims to examine the impacts of social and personal risk perception of COVID-19 and place images on place loyalty. The SmartPLS 3 was utilized to analyze the hypothesized relationship. The study questionnaire was developed according to measurement scales from the previous research. The questionnaire form comprised two parts where the former included a measurement scale of social and personal risk perception of COVID-19, cognitive and affective place image, and place loyalty, and the latter consisted of socio-demographic questions.

Figure 1.

A conceptual framework.

The measurement of the perceived risk was adapted from research by [27,34,73], and statements used to measure cognitive and affective place image from research by [13,16]. In addition, place loyalty was assessed with four statements adapted from Lee and Xue [74]. A 5-point Likert-type scale was employed in this research. The second part of the questionnaire was designed to collect socio-demographic characteristics such as gender, age, degree program, nationality, and length of residence.

3.2. Date Collection and Analysis

This research population comprises international students enrolled in degree programs such as bachelor’s, master’s, or doctoral programs. All respondents enrolled in degree programs differentiated from those who came to Korea for language or short-term training. International students pursuing degrees generally stay in Korea for at least three to six years to finish their studies. In order to improve validity and make a user-friendly questionnaire, the pilot study was conducted with staff in charge of international students in college and focus groups. As a result, they suggested minor adjustments to make it clear and readable for international students. As a result, the finalized questionnaire consisted of the research overview and the website link that hosted the questionnaire. The survey was conducted on 800 international students. Of the 800 questionnaires distributed, 780 surveys were returned. The number of valid samples was 774 after eliminating six incomplete data questionnaires.

The empirical investigation of hypothesized relationships was examined using the SmartPLS 3. Partial least squares (PLS) analysis was used with a bootstrapping technique applying 5000 samples. The PLS-SEM has been tested to be effective for complex research models [75] and mediating effects [76]. The data analysis was completed in two parts: Measurement Model Evaluation and Structure Model Evaluation [77] to investigate the prosed relationship of hypotheses.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Findings

Of the respondents, 55.8% (n = 432) were age from 26 to 31, 18 to 25 were 24.8% (n = 192), 31 to 36 were 15.4% (n = 119), and over 37 were 4% (n = 31). Approximately half of the respondents (50.8%) were in master’s degree program (n = 393), 29.5 % were in bachelor’s degree program (n = 228), and 19.8% were in doctoral course (n = 153). In total, 29.8% of the respondents were from Southeast Asia (n = 231), 24% came from America (n = 186), 17.1%, 13%, 9.3%, and 6.7% were from Africa, Central Asia, Europe, and Northeast Asia, respectively. When it comes to the length of residence, staying in Korea from 1 to 3 years accounted for 39.7% (n = 307), followed by 32.7% from 3 to 5 years (n = 253), 21.7%, 5.9% from 5 to 6 years (n = 168) and more than 6 years (n = 46), respectively. The gender distribution is approximately equal. There were 51.2% female (n = 396) and 48.8% male (n = 378) respondents.

4.2. Measurement Model Evaluation

The measurement model facilitated the assessment of reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. The convergent validity was assessed using factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). Table 1 demonstrates that all CR values ranged from 0.855 to 0.923, which falls in a reasonable range. Construct validity analysis demonstrated that the factor loadings of most observed variables should be above 0.7, ranging from 0.706 to 0.922 and AVE values ranging from 0.541 to 0.800 are above the threshold [77]. Thus, the measurement model’s internal consistency reliability and convergent validity were confirmed.

Table 1.

Result of the measurement model.

The results of the Fornell–Larcker criterion demonstrated that all potential constructs have discriminant validity. As can be seen from Table 2, the bold fonts that the square roots of AVEs on each construct are more significant than its correlation coefficient [78].

Table 2.

Analysis of Discriminant Validity.

4.3. Structural Model Evaluation

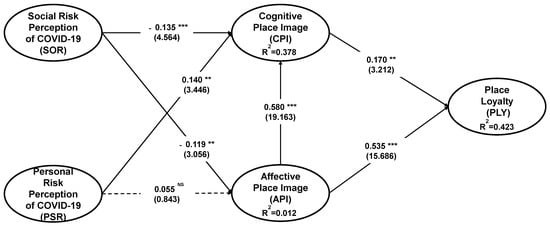

The statistical significance between variables was estimated using the bootstrapping resampling method with 5000 samples. Figure 2 shows the results from PLS-SEM that test the proposed research model. Social risk perception of COVID-19 has a significant relationship with cognitive place image (SOR→CPI) (β = −0.135; t = 4.564) and affective place image (SOR→API) (β = −0.119; t = 3.056), thus supporting H1a and H1b. Personal risk of COVID-19 had no significant impact on affective place image (PSR→API) (β = 0.055; t = 0.843), whereas personal risk perception of COVID-19 was significantly associated with cognitive place image (PSR→CPI) (β = 0.140; t = 3.446), meaning H2b is not accepted, but H2a is supported.

Figure 2.

Results of Structural Model (Notes: *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; NS, Not Significant).

The standardized path coefficient of the relationship between cognitive and affective place image (API→CPI) (β = 0.580; t = 19.163) indicates that API was a significant predictor of CPI. In addition, cognitive place image positively influenced place loyalty (CPI→PLY) (β = 0.170; t = 3.212) and affective place image is significantly related to place loyalty (API→PLY) (β = 0.535; t = 15.686). Thus, these results support H3, H6, and H7.

4.4. Hypotheses Testing

The effects social risk perception (SOR) had on the cognitive place image (CPI) and affective place image (API) were examined. As can be seen in Table 3, there was a significant negative relationship between social risk perception of COVID-19 and cognitive place image (β = −0.135, p < 0.001) and affective place image (β = −0.119, p < 0.01), supporting H1a and H1b. The personal risk perception of COVID-19 (PSR) had a significant influence on cognitive place image (β = 0.140, p < 0.05), and H2a was supported. The relationship between PSR and API showed only directional support, causing H2b to be rejected. Affective place image significantly affected cognitive place image (β = 0.580, p < 0.001), suggesting H3 was maintained. The mediation effects of place images were also examined.

Table 3.

Hypotheses Test Results.

Social risk perception of COVID-19 influenced place loyalty through cognitive place image (β = −0.023, p < 0.05), likewise, personal risk perception of COVID-19 also impacted place loyalty through cognitive place image (β = 0.024, p < 0.05). The mediating role of affective place image had a significant effect between social risk perception and place loyalty (β = −0.064, p < 0.01), supporting H5a. However, affective place image did not mediate the relationship between personal social risk perception and place loyalty, meaning H5b was not accepted. In addition, there was a significant relationship between cognitive place image and place loyalty (β = 0.170, p < 0.01) and affective place image and place loyalty (β = 0.535, p < 0.001); hence, H6 and H7 were supported.

4.5. The Moderating Effects of Gender

Multigroup analysis with parametric testing was performed in PLS to examine the gender moderating effects of seven paths. Table 4 summarizes the results of the PLS-SEM multigroup analysis. One out of seven paths (H8f) proved to differ significantly between males and females (p < 0.05). Gender moderated the relationship between cognitive place image and place loyalty with males (βm = 0.290, βf = 0.093, p < 0.05) due to cognitive place image having a stronger influence on males than females.

Table 4.

Result of PLS-SEM multigroup analysis.

Gender did not moderate the relationship between risk perception of COVID-19 and place image for paths H8a, H8b, H8c, and H8d. Females with higher coefficients on the paths were more likely to be influenced by the social perceived risk of COVID-19 on cognitive and affective place image (βm = −0.155, βf = −0.101; βm = −0.191, βf = −0.068). However, regarding the relationship between the personal risk of COVID-19 and place image, males were more likely to be affected by risk perception on cognitive place image, whereas a group of females showed higher coefficients on the path (βm = 0.183, βf = 0.082; βm = 0.072, βf = −0.081).

Likewise, gender also did not moderate the relationship between cognitive and affective image (H8e), but the path coefficients of H8e show that females were likely to be affected by affective image to cognitive image towards the place (βm = −0.556, βf = −0.608). Although the path coefficients of H8g were not significantly different, the affective image of the place may influence loyalty towards the place in that the results indicated that males would be more inclined to be loyal than females (βm = −0.534, βf = −0.518). However, the interactive effect of gender and cognitive place image are significantly associated with place loyalty (βm = 0.290, βf = 0.093), suggesting that the moderating effect of gender is supported, and thus, H8f is supported (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Results of PLA-SEM for Male and Female. Notes: *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; M = Male; F = Female).

5. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the relationships between social risk perception (SOR), personal risk perception (PSR) of COVID-19 and cognitive place image (CPI), affective place image (API), and place loyalty (PLY) constructs. We asked a question in the research title: ‘Can international students’ risk perception and place image create an advantage in safeguarding place loyalty in post-COVID-19 tourism?’; the answer is ‘Yes’. The findings presented in the research suggest that personal risk perception exerts a significant effect on cognitive place image and place loyalty despite the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regarding tourists’ decision making, risk perceptions play an important role in mitigating negative perceptions, helping to create a positive place image, and setting sustainable management practices [79]. With a multi-aspect construct, perceived risk can be categorized into several types of risk [80]. Previous studies on risk perception investigated that it is shaped by internal and external factors closely related to themselves and information sources such as media and destination image [30], respectively. Given that this study attempted to identify the influence relationship between risk perception and place image using internal factors and social and personal risk perceptions which determine the interpretation of the informed risks.

According to prior research on trust and risk perception [36], people believe they are less likely to be affected by a personal risk than others. Such an optimistic bias against the likelihood was presented in the present research. The findings on social risk perception negatively influenced cognitive and affective place image, which confirmed that perceived risk negatively impacts the place image because the perception is linked to the image of the place [70]. In contrast, personal risk perception was found not to affect the affective place image and significantly affects the cognitive place image. These findings were congruent with comparative optimism bias and third-person perception toward COVID-19 [36,38].

According to the prior research on the language challenge of COVID-19, linguistic minorities worldwide struggle to acquire such health information in their native language [81]. Focusing on the case of international students who likely feel insecure due to language barriers and citizenship status [82], have a low level of trust in official communications, and are vulnerable to misinformation and fake news to deal with health information disparities in an online community as well [83]. Such information disparities would have resulted in conflicting findings of risk perceptions from personal and social perspectives.

However, in the context of risk, the risk perception of the situation is a stronger determinant of behavior intention than actual existing risks [84], as risk perception is a personal evaluation of the possibility of unfavorable outcomes from an individual’s perspective [29]. When it comes to decision making, the majority of international students do not consider COVID-19 risk when choosing where to study abroad [85]; thus, they are likely to have a lower risk perception of COVID-19. Such empirical evidence aligns with the research results that international students’ personal risk perception positively affects their cognitive image, contrary to social risk perception.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings also suggested that cognitive and affective place images positively correlate with place loyalty. Specifically, the affective image seemed stronger (0.535) in predicting place loyalty than the cognitive image (0.17), demonstrating that feelings are better predictors of behavioral intentions. The findings were in line with the prior studies, which present the affective image as a significant predictor of place loyalty in each image form [53,86].

Furthermore, we found that cognitive image could mediate between social risk perception and personal social risk perception of COVDI-19 and place loyalty. Based on the prior research, the perceived risk is highly correlated to travel intention to a specific destination since increased perceived susceptibility to getting infected by COVID-19 while traveling [87]. Therefore, the findings affirm that social and personal risk perception indirectly affects place loyalty via cognitive place image. Therefore, the findings suggested that cognitive place image is an essential variable influencing whether risk perception of COVID-19 positively or negatively correlates with place loyalty, showing that risk perception is a stronger determinant of destination choice than actual existing risks [84].

However, there has been insufficient empirical research testing how the place image mediates perceived risk to place loyalty, and their relationships remain unclear. This research introduced cognitive place image and affective place image as mediators between risk perception of COVID-19 with the perspective of social and personal and place loyalty.

The results showed the moderating role of gender, which can moderate the relationship between risk perception of COVID-19, place image, and place loyalty. In this study, gender did not moderate the link between social and personal perceived risk and place images, affective place image, and place loyalty. Nevertheless, only the relationship between cognitive place image and place loyalty was significantly affected by gender. Some researchers suggested that gender moderated the influence of tourists’ risk perceptions on the image of place and place loyalty [52,70]. Mainly, females are sensitive to security risks [88] and physical risks, such as sexual harassment or assault [67]. Conversely, this study demonstrated that gender did not moderate risk perception and place image.

Because gendered risk perceptions vary significantly with the type of risks [66], the result can differ depending on the types of risk perception. In this study, the type of risk perception of COVID-19 was internal factors representing social and personal risk perception which are somewhat different from uncontrollable risk [70]. The different types of risk perception may cause contrary results to previous findings since internal factors are interpretation and perception of the informed risks [35]. In addition, gendered risk perceptions vary significantly with how destinations manage specific risks [66]. For example, Korea has effectively managed to contain the virus without full mandatory lockdowns. Many countries studied how Korea served as the “Global Golden Standard” in responding to COVID-19 [89].

Furthermore, QS Higher Education Briefing [85] reported, based on a survey of students in 56 countries, that fear of contracting COVID-19 is no longer an issue for international students and does not impact their decision making. Thus, fear of contracting COVID-19 is almost a non-factor in most international students’ decision making about where to study abroad. In this regard, international students are likely to have a lower risk perception of COVID-19. Consequently, gender moderates the relationship between cognitive place image and place loyalty, yet gender does not affect the relationship between risk perception of COVID-19 and place image.

Therefore, this study into (1) the relationship between risk perception of COVID-19, place image, and place loyalty constructs, (2) how place image can mediate between risk perception of COVID-19 and place loyalty, and (3) how gender can affect the proposed hypotheses constructs may fulfill such theoretical needs.

6.2. Management Implications

This research provides insightful implications for tourism and higher education practitioners and academic contributions. An important finding of the study is that the personal risk perception of COVID-19 does not undermine an individual’s cognitive place image, while social risk perception does. The government and higher education practitioners should consider providing epidemic prevention knowledge and health protection measures such as public advice and notice through media or SNS for international students and introducing quarantine information in English for their understanding. Besides, as the public health threat caused by COVID-19 still exists, it is vital to provide spot-on and timely information about the disease and its prevention and treatment to cope with fear and uncertainty on personal and social levels [90]. Consequently, international students can encourage prospective tourists such as relatives and friends from inside and outside their home countries to visit their host countries [91].

The findings revealed that social and personal risk perception of COVID-19 has a stronger influence on place loyalty when mediated by cognitive image. Likewise, social risk perception significantly affects place loyalty when mediated by affective place image. Because the image of the place is important to develop place loyalty, it is necessary to reflect the opinions and perspectives of international students when establishing a destination marketing strategy or development for international visitors. Additionally, practitioners of host university management and related organizations need to raise awareness of supporting service programs for international students [92].

Besides, all practitioners in tourism, higher education, and local governments should take measures to address language barriers for international visitors and residents. The language barrier is one of the biggest challenges for foreign residents in Korea and international visitors [93]. Therefore, various languages should be provided at the venue for international visitors to understand Korean culture and organize cultural heritage guides and free guide tours in customized languages. Such efforts will positively affect the cognitive place image, and a good place image will positively affect loyalty, although the crisis of COVID-19 still exists.

Regarding gender differences, in this study, males are more likely to be affected by cognitive place image when they evaluate place loyalty. It is important to understand the needs of males in detail and focus on the cognitive attributes of the place. Even though the findings showed a relationship between cognitive place image and place loyalty moderated with gender, the needs of both males and females are important.

6.3. Limitation and Future Studies

Despite its theoretical and practical implications, there are several limitations that future studies should overcome. First, the collected data to ensure the validity of this study was gathered from international students selected from Global Korea Scholarship (GKS) scholars sponsored by the Korean government, specific to degree program scholars. Such a limitation prevented generalizing causality. In order to overcome the limitations above, considering self-funded international students would be a reasonable remedy. Second, the study examined the relationship between risk perception of COVID-19, place image, and place loyalty for international students. Thus, expanding the research model would be worth examining other international groups, such as immigrants or multicultural families. It will help tourism researchers understand differences in risk perceptions, place image, and loyalty among different groups and support institutions and local governments in establishing strategies targeting an inbound market.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.L.; methodology, N.L.; software, N.L.; validation, B.-S.K.; investigation, B.-S.K.; resources, N.L.; data curation, B.-S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, N.L.; writing—review and editing, B.-S.K.; visualization, N.L.; supervision, B.-S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, C.X.; Wang, L.; Rickly, J.M. Non-interaction and identity change in COVID-19 tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 89, 103211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Song, H. Intercultural sensitivity and tourism patterns among international students in Korea: Using a latent profile analysis. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, K. The outbreak of COVID-19 and its impact in South Korea’s tourism: A hope in domestic tourism. J. Appl. Sci. Travel Hosp. 2021, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Kock, F. The coronavirus pandemic–A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. Higher Education. Available online: http://english.moe.go.kr/sub/infoRenewal.do?m=0305&page=0305&s=english (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- López, X.P.; Fernández, M.F.; Incera, A.C. The economic impact of international students in a regional economy from a tourism perspective. Tour. Econ. 2016, 22, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L. An ethnographic study of the friendship patterns of international students in England: An attempt to recreate home through conational interaction. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2009, 48, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Bae, S.Y. Understanding the travel motivation and patterns of international students in Korea: Using the theory of travel career pattern. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Ryan, C. The role of Chinese students as tourists and hosts for overseas travel. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 16, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Chiu, Y.-H.; Tian, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Q. Safety or travel: Which is more important? The impact of disaster events on tourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, M.; Ryan, C.; Pan, S. Using Chinese travel blogs to examine perceived destination image: The case of New Zealand. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganji, S.F.G.; Johnson, L.W.; Sadeghian, S. The effect of place image and place attachment on residents’ perceived value and support for tourism development. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Biran, A.; Sit, J.; Szivas, E.M. Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C.; Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Çalışkan, C.; Karakuş, Y. Role of place image in support for tourism development: The mediating role of multi-dimensional impacts. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Quintero, A.M.D. Understanding the Effect of Place Image and Knowledge of Tourism on Residents’ Attitudes Towards Tourism and Their Word-of-Mouth Intentions: Evidence from Seville, Spain. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min-En, A.T. Travel stimulated by international students in Australia. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2006, 8, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Kim, I. Chinese international students’ psychological adaptation process in Korea: The role of tourism experience in the host country. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, A.; Davis, D.; Meares, D.; Pearce, D. Global Student Mobility 2025: Forecasts of the Global Demand for International Higher Education; IDP Education: Melbourne, Australia, 2002; Available online: https://www.foresightfordevelopment.org/sobipro/55/333-global-student-mobility-2025-forecasts-of-the-global-demand-for-international-higher-education (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Lim, B.; Kyoungseo Hong, E.; Mou, J.; Cheong, I. COVID-19 in Korea: Success based on past failure. Asian Econ. Pap. 2021, 20, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Shanka, T.; Pope, J. Investigating the significance of VFR visits to international students. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2004, 14, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shani, A.; Uriely, N. VFR tourism: The host experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Dwyer, L. The VFR and migration nexus—The impacts of migration on inbound and outbound Australian VFR travel. VFR Travel Res. Int. Perspect. 2015, 69, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.-M. Korea Revises Visa Rules to Secure More Foreign Workers for Shipbuilders. The Korea Times. 19 April 2022. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/tech/2022/04/419_327609.html (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Moreira, P. Stealth risks and catastrophic risks: On risk perception and crisis recovery strategies. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 23, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cori, L.; Bianchi, F.; Cadum, E.; Anthonj, C. Risk perception and COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintal, V.A.; Lee, J.A.; Soutar, G.N. Risk, uncertainty and the theory of planned behavior: A tourism example. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Mavondo, F. Cultural differences in travel risk perception. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2006, 20, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, M. Risk and uncertainty in travel decision-making: Tourist and destination perspective. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, V.C.; Qu, H.; Chu, R. The relationship between vacation factors and socio-demographic and travelling characteristics: The case of Japanese leisure travellers. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R.; Cook, F.L. The mass media and judgments of risk: Distinguishing impact on personal and societal level judgments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 47, 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaohua, W.; Xigen, L. Effects of mass media exposure and social network site involvement on risk perception of and precautionary behavior toward the haze issue in China. Int. J. Commun. 2017, 11, 3975–3997. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Chen, S.; Kong, L.; Liu, W. Analysis of risk perceptions and related factors concerning COVID-19 epidemic in Chongqing, China. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkady, D.; Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Virtual reality as a travel substitution tool during COVID-19. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2021; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 452–463. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.L.; Nair, V. Risk perception study in tourism: Are we really measuring perceived risk? Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 144, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Luchsinger, L.; Bearth, A. The impact of trust and risk perception on the acceptance of measures to reduce COVID-19 cases. Risk Anal. 2021, 41, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. Optimistic biases about personal risks. Science 1989, 246, 1232–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, W.P. The third-person effect in communication. Public Opin. Q. 1983, 47, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulding, K.E. General systems theory—The skeleton of science. Manag. Sci. 1956, 2, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Haider, D.; Rein, I. There’s no place like our place! The marketing of cities, regions, and nations. Futurist 1993, 27, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J.L. Motivations for pleasure vacation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E.Y.T.; Jahari, S.A. Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Shani, A.; Belhassen, Y. Testing an integrated destination image model across residents and tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Phou, S. A closer look at destination: Image, personality, relationship and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of tourists’ loyalty to Mauritius: The role and influence of destination image, place attachment, personal involvement, and satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, G.C.; Mak, A.H. Exploring the discrepancies in perceived destination images from residents’ and tourists’ perspectives: A revised importance–performance analysis approach. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1124–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallarza, M.G.; Saura, I.G.; García, H.C. Destination image: Towards a conceptual framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Chung, J.Y.; Gao, J.; Lin, Y.-H. Destination familiarity and favorability in a country-image context: Examining Taiwanese travelers’ perceptions of China. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Ryan, C. Destination positioning analysis through a comparison of cognitive, affective, and conative perceptions. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, K.; Zehrer, A.; Müller, S. Perceived destination image: An image model for a winter sports destination and its effect on intention to revisit. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Ivkov, M.; Kim, S.S. Destination loyalty explained through place attachment, destination familiarity and destination image. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, X.; Cai, L.A.; Lu, L. Destination image and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Santana, A.; Moreno-Gil, S. Understanding tourism loyalty: Horizontal vs. destination loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Wang, Y.-C.; Liu, C.-R.; Huang, W.-S. Festival attachment: Antecedents and effects on place attachment and place loyalty. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2019, 10, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A.; Rodger, K.; Taplin, R.H. Developing a better understanding of the complexities of visitor loyalty to Karijini National Park, Western Australia. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, V.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Payini, V.; Woosnam, K.M.; Mallya, J.; Gopalakrishnan, P. Visitors’ place attachment and destination loyalty: Examining the roles of emotional solidarity and perceived safety. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Tsai, D. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Hsu, C.H. Effects of travel motivation, past experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B.; Lawton, L.J. Visitor loyalty at a private South Carolina protected area. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Zins, A.H.; Silva, F. Why do tourists persist in visiting the same destination? Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A. Tourism and Gender: Embodiment, Sensuality and Experience; CABI: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, S.; Hirose, M. Does gender affect media choice in travel information search? On the use of mobile Internet. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, A.; Burgess, B. Gender differences in cognitive and affective impulse buying. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2003, 7, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoglu, B.B. Are information quality and source credibility really important for shared content on social media? The moderating role of gender. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; van der Veen, R.; Song, Z. The impact of coping strategies on occupational stress and turnover intentions among hotel employees. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2018, 27, 926–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Khoo-Lattimore, C.; Arcodia, C. A systematic literature review of risk and gender research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Cohen, S.; Hanna, P. Hitchhiking travel in China: Gender, agency and vulnerability. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 103002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T.K.; Mura, P. The ‘normality of unsafety’-foreign solo female travellers in India. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wong, P.P.W.; Zhang, Q. Travellers’ destination choice among university students in China amid COVID-19: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, R.R.; León, C.J.; Carballo, M.M. Gender as moderator of the influence of tourists’ risk perception on destination image and visit intentions. Tour. Rev. 2021, 77, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Line, N.D.; Goh, B. Experiential value, relationship quality, and customer loyalty in full-service restaurants: The moderating role of gender. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 679–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, N.M. Passenger satisfaction with airline service quality in Malaysia: A structural equation modeling approach. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 10, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A. Demystifying the effects of perceived risk and fear on customer engagement, co-creation and revisit intention during COVID-19: A protection motivation theory approach. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Xue, K. A model of destination loyalty: Integrating destination image and sustainable tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U.; Nadeem, R.D.; Nawaz, S. Cross-country evidence on project portfolio success in the Asia-Pacific region: Role of CEO transformational leadership, portfolio governance and strategic innovation orientation. Cogent. Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1727681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medhekar, A.; Wong, H.Y.; Hall, J.E. Health-care providers perspective on value in medical travel to India. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, R.R.; León, C.J.; Carballo, M.M. The perception of risk by international travellers. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avineri, N.; Graham, L.R.; Johnson, E.J.; Riner, R.C.; Rosa, J. Introduction: Reimagining language and social justice. In Language and Social Justice in Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, I.C.; Choi, L.J. Staying connected during COVID-19: The social and communicative role of an ethnic online community of Chinese international students in South Korea. Multilingua 2020, 39, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piller, I.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. Linguistic diversity in a time of crisis: Language challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. Multilingua 2020, 39, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G.; Reichel, A. Tourist destination risk perception: The case of Israel. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2006, 14, 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICEF Monitor. Survey Finds International Students More Focused on the Future, and Careers in Particular. Available online: https://monitor.icef.com/2022/06/survey-finds-international-students-are-focused-on-the-future-and-careers-in-particular/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Afshardoost, M.; Eshaghi, M.S. Destination image and tourist behavioural intentions: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyanto, I.; Wiblishauser, M.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Schroeder, A. The dynamics of travel avoidance: The case of Ebola in the US. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.-D.; Altinay, L.; Zhuang, W.-L.; Chen, K.-T. Work engagement and job burnout? Roles of regulatory foci, supervisors’ organizational embodiment and psychological ownership. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R. The challenges of expanding rapid tests to curb COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 324, 1813–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.-T.; Li, W.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, Y.; Rao, W.-W.; Zeng, L.-N.; Lok, G.K.; Chow, I.H.; Cheung, T.; Hall, B.J. Timely research papers about COVID-19 in China. Lancet 2020, 395, 684–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aktan, M.; Zaman, U.; Nawaz, S. Examining destinations’ personality and brand equity through the lens of expats: Moderating role of expat’s cultural intelligence. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 849–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Kim, B.-S. International Student Engagement for Sustainability of Leisure Participation: An Integrated Approach of Means-End Chain and Acculturation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-H. Discrimination or Not? Museum Denies Foreigners Access to Programs Citing Language Barrier. The Korea Herald. 13 December 2021. Available online: http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20211213000681 (accessed on 17 June 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).