The Effect of Safety Attitudes on Coal Miners’ Human Errors: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Safety Attitudes on Human Errors

2.2. The Mediating Role of Situational Awareness

2.3. The Moderating Role of Task Complexity

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection and Sampling

3.2. Measures

- (1)

- Safety attitudes: A scale developed by Seaboch was adopted [53]. It consists of 13 questions, five of which are about safety cognitive attitudes, such as “I think safety accidents at work can be prevented”, three questions about safety affective attitudes, such as “I am willing to wear safety protection equipment for work”, and five questions about safety behavioral tendencies, such as “Before starting work, I tend to check equipment and facilities for safety hazards”.

- (2)

- Human errors: The 13-item instrument created by Shakerian [54] was employed to measure miners’ human errors, with higher scores indicating higher levels of human errors in a person’s work. These included items such as “Have you ever started doing something before bringing or preparing its necessary tool due to a mental and job engagement?”.

- (3)

- Situational awareness: The 10-item scale created by Sneddon et al. [45] was adopted to measure miners’ situational awareness. A higher score demonstrated a higher level of situational awareness. Example items are “I find it easy to keep track of everything that is going on around me”.

- (4)

- Task complexity: Task complexity was measured using the perceived task difficulty questionnaire developed by Robinson [55], which measures coal miners’ perceived task complexity in five dimensions: difficulty, stress, confidence, interest, and motivation, with five items, such as, “I think my job task is a bit difficult”.

- (5)

- Control variable: To avoid the impact of demographic variables on the research results, this study set the following variables as controls—age, gender, education level, and working years.

3.3. Data Analysis Procedures

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.3. Results of Hypothesis Testing

4.3.1. Testing Results of Main Effects

4.3.2. Mediating Role of Situational Awareness

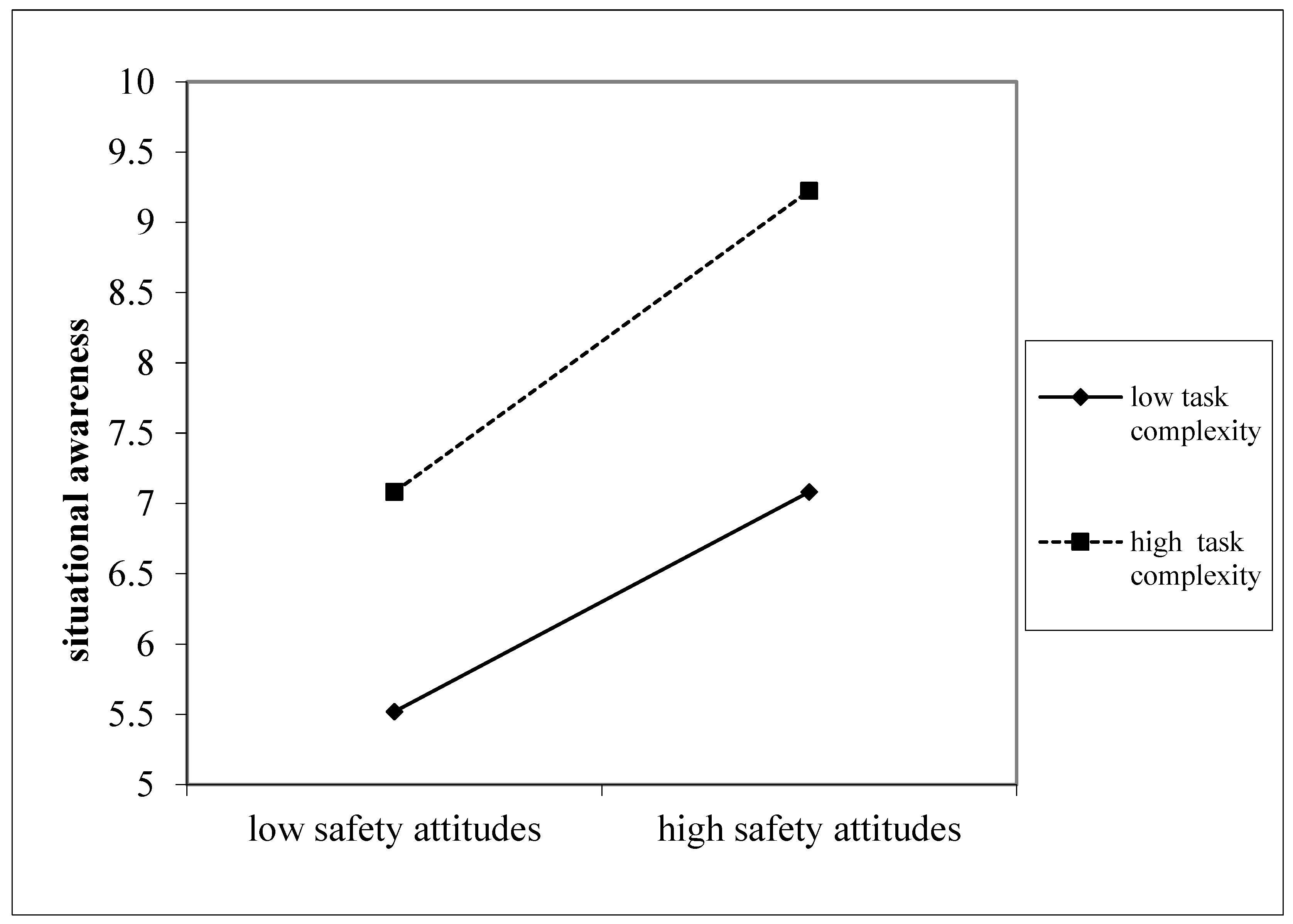

4.3.3. Moderating Effect

4.3.4. The Moderated Mediating Effect

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implication

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations of the Current Study and Avenues for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, M.; Yang, S.W.; Sun, Z.M.; Wu, H. Study on framework and development prospects of intelligent mine. Coal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 45, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, S. Coal mine safety production situation and management strategy. Manag. Eng. 2014, 14, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano, B.; Pettinato, M.; Currò, F.; Reverberi, A.P. A field study on human factor and safety performances in a downstream oil industry. Saf. Sci 2022, 153, 105795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.; Chou, H.; Chen, Y.; Shiao, H. Regulatory overview of digital I&C system in Taiwan Lungmen Project. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2008, 35, 877–889. [Google Scholar]

- Zio, E. Reliability engineering: Old problems and new challenges. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safe. 2009, 94, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohammadfam, I.; Mahdinia, M.; Soltanzadeh, A.; Aliabadi, M.M.; Soltanian, A.R. A path analysis model of individual variables predicting safety behavior and human error: The mediating effect of situation awareness. Int. J. Ind. Ergonom. 2021, 84, 103144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leplat, J.; Rasmussen, J. Analysis of human errors in industrial incidents and accidents for improvement of work safety. Accident. Anal. Prev. 1984, 16, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xue, Y.J.Y.; Fu, G. Statistical analysis of the action path of unsafe act causes in general aviation accidents. Saf. Environ. Eng. 2018, 25, 131–138. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Minyan, X.; Xuehua, T. Human-machine interface design rules of electromechanical product based on knowledge of cognitive psychology. Packag. Eng. 2009, 30, 140–142. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Vinodkumar, M.N.; Bhasi, M. Safety management practices and safety behaviour: Assessing the mediating role of safety knowledge and motivation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 2082–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, N.; Fu, G.; Yan, M.; Kim, Y.-C. The safety attitudes of senior managers in the Chinese coal industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 11, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A. Perceptions of safety at work: A framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, Y.A.; Davis, A.L.; Taylor, J.A. Ladders and lifting: How gender affects safety behaviors in the fire service. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2017, 32, 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, K.Y.; Spitzmueller, C.; Cigularov, K.; Thomas, C.L. Linking safety knowledge to safety behaviours: A moderated mediation of supervisor and worker safety attitudes. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Blackman, A. Linking emotional intelligence to safety performance: The roles of situational awareness and safety training. J. Saf. Res. 2021, 78, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šeibokaitė, L.; Endriulaitienė, A.; Markšaitytė, R.; Slavinskienė, J. Improvement of hazard prediction accuracy after training: Moderation effect of driving self-efficacy and road safety attitudes of learner drivers. Saf. Sci. 2022, 151, 105742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monazzam, M.R.; Soltanzadeh, A. The relationship between the worker’s safety attitude and the registered accidents. J. Res. Health Sci. 2009, 9, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, P.P.; Liao, P.; Gou, Z. Personality factors and safety attitudes predict safety behavior and accidents in elevator workers. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2018, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gharibi, V.; Mortazavi, S.B.; Jafari, A.J.; Malakouti, J.; Abadi, M.B.H. The relationship between workers’ attitude towards safety and occupational accidents experience. Int. J. Occup. Hyg. 2016, 8, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Luo, X.; Gao, J.; Yin, W. Impact of safety attitude on the safety behavior of coal miners in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ledesma, R.D.; Tosi, J.D.; Díaz-Lázaro, C.M.; Poó, F.M. Predicting road safety behavior with implicit attitudes and the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Saf. Res. 2018, 66, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.A. A Study on the influence of the perception of personal information security of youth on security attitude and security behavior. J. Korea Ind. Inf. Syst. Res. 2019, 24, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tett, R.P.; Burnett, D.D. A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 500–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, W.; Li, Y.; Wu, C. Task complexity matters: The influence of trait mindfulness on task and safety performance of nuclear power plant operators. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2013, 55, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W.C.; Ahn, T.H. A classification of electrical component failures and their human error types in South Korean NPPs during last 10 years. Nu. Eng. Technol. 2019, 51, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.-X.; Liu, R.; Liu, H.-C.; Jiang, S. Two decades on human reliability analysis: A bibliometric analysis and literature review. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 2020, 151, 107969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.; Bedford, T.; Pollard, S.J.; Soane, E. Human reliability analysis: A critique and review for managers. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, S.; You, M.; Li, D.; Liu, J. Identifying coal mine safety production risk factors by employing text mining and Bayesian network techniques. Process. Saf. Environ. 2022, 162, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.; Li, S.; Li, D.; Qing, X. Study on the influencing factors of miners’ unsafe behavior propagation. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, K.; Cao, Q.; Xie, C.; Qu, N.; Zhou, L. Analysis of intervention strategies for coal miners’ unsafe behaviors based on analytic network process and system dynamics. Saf. Sci. 2019, 118, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.; Cox, T. The structure of employee attitudes to safety: A European example. Work Stress 1991, 5, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmerdam, A.; Newnam, S.; Wang, Y.; Sheppard, D.; Griffin, M.; Stevenson, M. High performance workplace systems’ influence on safety attitudes and occupational driver behaviour. Saf. Sci. 2018, 106, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yin, W.; Wu, C.; Li, Y. Development and validation of a safety attitude scale for coal miners in China. Sustainability 2017, 12, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mearns, K.; Flin, R. Risk perception and attitudes to safety by personnel in the offshore oil and gas industry: A review. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 1995, 8, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, C.E.; Rickson, R.E. Environmental knowledge and attitudes. J. Environ. Educ. 1976, 8, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, T.; Mebarki, A. Impact of safety attitude, safety knowledge and safety leadership on chemical industry workers’ risk perception based on structural equation modelling and system dynamics. J. Loss. Prevent. Proc. 2021, 72, 104542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Liu, B.; Li, H.; Yang, S.; Li, Y. The effects of safety attitude and safety climate on flight attendants’ proactive personality with regard to safety behaviors. J. Air. Transp. Manag. 2019, 78, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Shi, Y.; Bai, L.; Tang, K.; Suzuki, K.; Nakamura, H. Modeling effects of driver safety attitudes on traffic violations in China using the theory of planned behavior. Iatss. Res. 2022, 46, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhai, H.; Chan, A.H.S. Development of scales to measure and analyze the relationship of safety consciousness and safety citizenship behavior of construction workers: An empirical study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ziemke, T.; Schaefer, K.E.; Endsley, M. Situation awareness in human-machine interactive systems. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2017, 46, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Bradley, J.C.; Wallace, J.C.; Burke, M.J. Workplace safety: A meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1103–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caponecchia, C.; Zheng, W.Y.; Regan, M.A. Selecting trainee pilots: Predictive validity of the wombat situational awareness pilot selection test. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 73, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, P.M.; Plant, K.L. Distributed situation awareness: From awareness in individuals and teams to the awareness of technologies, sociotechnical systems, and societies. Appl. Ergon. 2022, 98, 103599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, P.W.; Goldenhar, L.M. A qualitative study examining the influences on situation awareness and the identification, mitigation and escalation of recognised patient risk. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2014, 23, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, A.; Mearns, K.; Flin, R. Stress, fatigue, situation awareness and safety in offshore drilling crews. Saf. Sci. 2013, 56, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, S.; Colombo, S.; Manca, D. The role of situation awareness for the operators of process industry. 5th international conference on safety and environment in the process and power industry. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2012, 26, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Happee, R.; de Winter, J.C. Take over! A video-clip study measuring attention, situation awareness, and decision-making in the face of an impending hazard. Transport. Res. F-Traf. 2020, 72, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, V.; Lobjois, R.; Benguigui, N. The effects of driving environment complexity and dual tasking on drivers’ mental workload and eye blink behavior. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic. Psychol. Behav. 2016, 40, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussini, E.; Berchicci, M.; Bianco, V.; Perri, R.L.; Quinzi, F.; Di Russo, F. Effect of task complexity on motor and cognitive preparatory brain activities. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2021, 159, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topi, H.; Valacich, J.S.; Hoffer, J.A. The effects of task complexity and time availability limitations on human performance in database query tasks. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2005, 62, 349–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Luo, Z.; Dai, L. An experimental study on the effects of task complexity and knowledge and experience level on SA, TSA and workload. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2021, 376, 111112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, Z. Task complexity: A review and conceptualization framework. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2012, 42, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaboch, T.R. Effects of Safety Instruction upon Safety Attitudes and Knowledge of University Students Enrolled in Selected Agricultural Engineering Courses. Master’s Thesis, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Shakerian, M.; Choobineh, A.; Jahangiri, M.; Hasanzadeh, J.; Nami, M. Is “Invisible Gorilla” self-reportedly measurable? Development and validation of a new questionnaire for measuring cognitive unsafe behaviors of front-line industrial workers. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2019, 27, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, P. Task complexity, task difficulty and task production: Exploring interactions in a componential framework. Appl. Linguist. 2001, 22, 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, D.; Liu, Z.; Diao, X.; Tan, H.; Qu, X.; Zhang, T. Antecedents of self-reported safety behaviors among commissioning workers in nuclear power plants: The roles of demographics, personality traits and safety attitudes. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2021, 53, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouabenan, D.R.; Ngueutsa, R.; Mbaye, S. Safety climate, perceived risk, and involvement in safety management. Saf. Sci. 2015, 77, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaw, J.D.; Gupta, N. Job complexity, performance, and well-being: When does supplies-values fit matter? Pers. Psychol. 2004, 57, 847–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mario, M.; Gracia, F.; Tomás, I.; José, M.P. Leadership and employees’ perceived safety behaviours in a nuclear power plant: A structural equation model. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 1118–1129. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Category | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 97.9 |

| Female | 2.1 | |

| Age | 18–25 years old | 4.1 |

| 26–35 years old | 26.4 | |

| 36–45 years old | 53.3 | |

| 46–55 years old | 13.0 | |

| Over 56 years old | 3.2 | |

| Educational Background | Less than high school | 33.7 |

| High school | 34.6 | |

| College | 17.5 | |

| Master’s degree | 14.2 | |

| Working years | 0–5 years | 3.3 |

| 6–10 years | 22.8 | |

| 11–15 years | 33.4 | |

| 16–20 years | 28.5 | |

| More than 20 years | 12.0 |

| Variable | Cronbach’s α | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|

| safety attitudes | 0.951 | 0.522 | 0.934 |

| Situational awareness | 0.934 | 0.507 | 0.911 |

| human errors | 0.947 | 0.513 | 0.932 |

| task complexity | 0.864 | 0.541 | 0.855 |

| χ2 | χ | RMSEA | SRMR | TLI | CFI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothetical model | 967.031 | 773 | 1.296 | 0.032 | 0.042 | 0.970 | 0.972 |

| Three-factor model | 2043.543 | 776 | 2.633 | 0.081 | 0.104 | 0.806 | 0.817 |

| Two-factor model | 2814.310 | 778 | 3.617 | 0.103 | 0.116 | 0.690 | 0.706 |

| Single-factor mode | 3293.888 | 779 | 4.23 | 0.115 | 0.127 | 0.617 | 0.636 |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.17 | 0.373 | |||||||

| 2. Age | 2.85 | 0.817 | −0.011 | ||||||

| 3. Education | 2.58 | 0.965 | 0.049 | −0.029 | |||||

| 4. Working years | 3.24 | 1.039 | −0.018 | 0.052 | −0.861 ** | ||||

| 5. Safety attitudes | 2.87 | 0.977 | 0.044 | −0.021 | 0.078 | −0.077 | |||

| 6. Situational awareness | 2.85 | 0.932 | 0.078 | 0.017 | 0.121 | −0.113 | 0.536 ** | ||

| 7. Human errors | 2.82 | 0.984 | −0.047 | −0.041 | 0.079 | 0.117 | −0.662 ** | −0.513 ** | |

| 8. Task complexity | 2.80 | 0.897 | 0.082 | 0.045 | 0.074 | −0.052 | 0.074 | 0.587 ** | −0.248 ** |

| Variable | Situational Awareness | Human Errors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Gender | 0.130 | 0.028 | 0.024 | −0.056 | −0.028 | −0.026 |

| Age | 0.036 | 0.005 | 0.013 | −0.073 | −0.046 | −0.065 |

| Education | 0.056 | 0.004 | −0.009 | 0.123 | 0.136 | 0.135 |

| Working years | −0.021 | −0.039 | −0.047 | 0.164 | 0.167 | 0.159 |

| Safety attitudes | 0.504 *** | 0.469 *** | 0.484 *** | −0.663*** | −0.547 *** | |

| Situational awareness | −0.536 *** | −0.229 *** | ||||

| Task complexity | 0.568 *** | 0.558 *** | ||||

| Safety attitudes × Task complexity | 0.164 *** | |||||

| R2 | 0.298 *** | 0.591 *** | 0.615 *** | 0.450 *** | 0.273 *** | 0.483 *** |

| F | 20.329 | 57.526 | 54.251 | 39.213 | 18.010 | 37.181 |

| Indirect Effect | Standard Error | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Task Complexity(−SD) | −0.077 | 0.024 | [−0.126, −0.034] |

| High Task Complexity (+SD) | −0.145 | 0.043 | [−0.231, −0.063] |

| Difference | −0.068 | 0.026 | [−0.126, −0.023] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niu, L.; Zhao, R. The Effect of Safety Attitudes on Coal Miners’ Human Errors: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9917. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169917

Niu L, Zhao R. The Effect of Safety Attitudes on Coal Miners’ Human Errors: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):9917. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169917

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Lixia, and Rui Zhao. 2022. "The Effect of Safety Attitudes on Coal Miners’ Human Errors: A Moderated Mediation Model" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 9917. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169917

APA StyleNiu, L., & Zhao, R. (2022). The Effect of Safety Attitudes on Coal Miners’ Human Errors: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability, 14(16), 9917. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169917