Does Park Size Affect Green Gentrification? Insights from Chongqing, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Explanation of Green Gentrification Formation

2.2. Green Gentrification and Its Characteristics

2.3. Research Methods

3. Data and Methodology

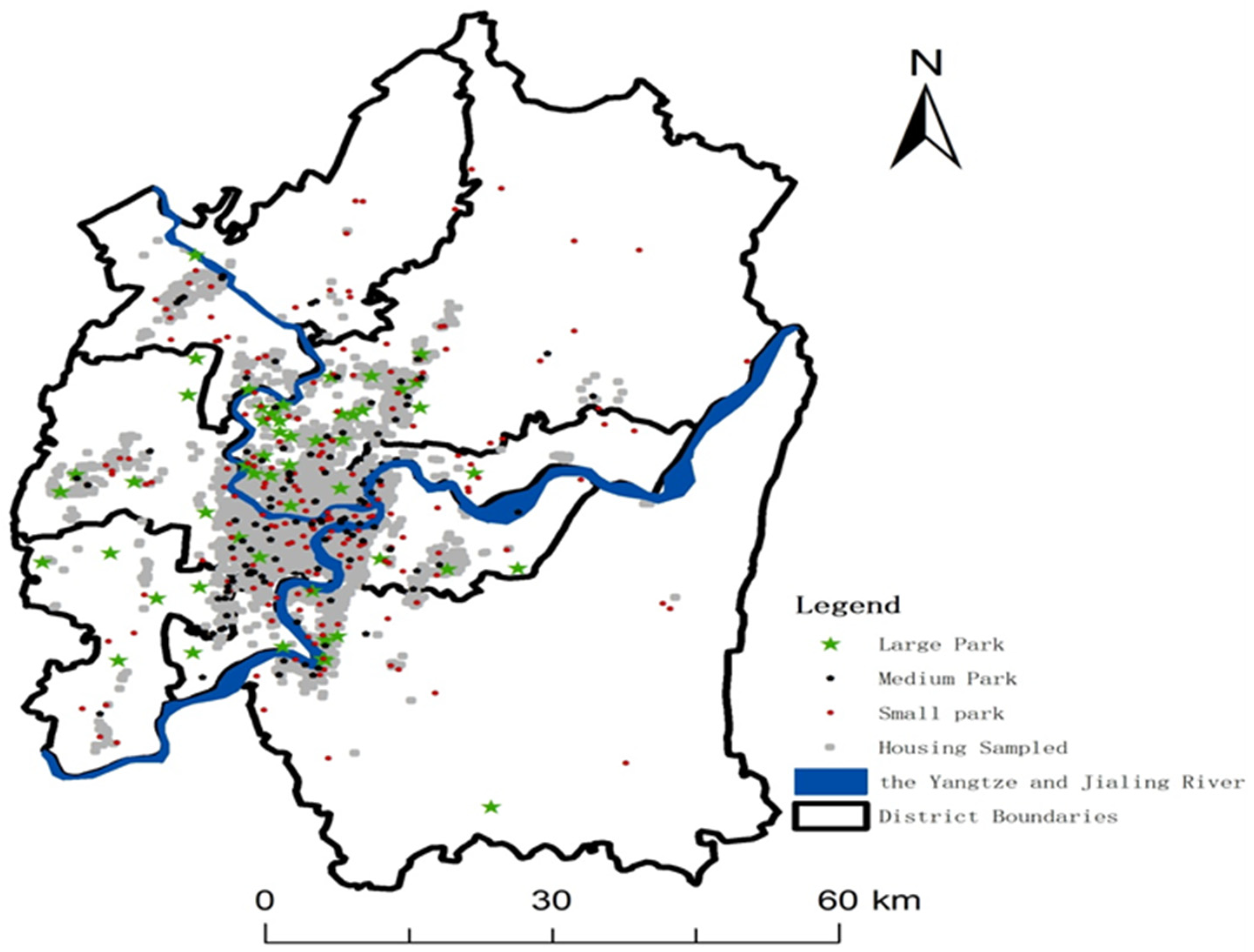

3.1. Research Area

3.2. Research Methods

3.2.1. Hedonic Price Model

3.2.2. Geographically Weighted Regression Model

3.2.3. Typical Case Investigation

3.3. Residential Characteristics and Data Sources

4. Results

4.1. Phase I: The Global Regression

4.2. Phase II: The Local Regression

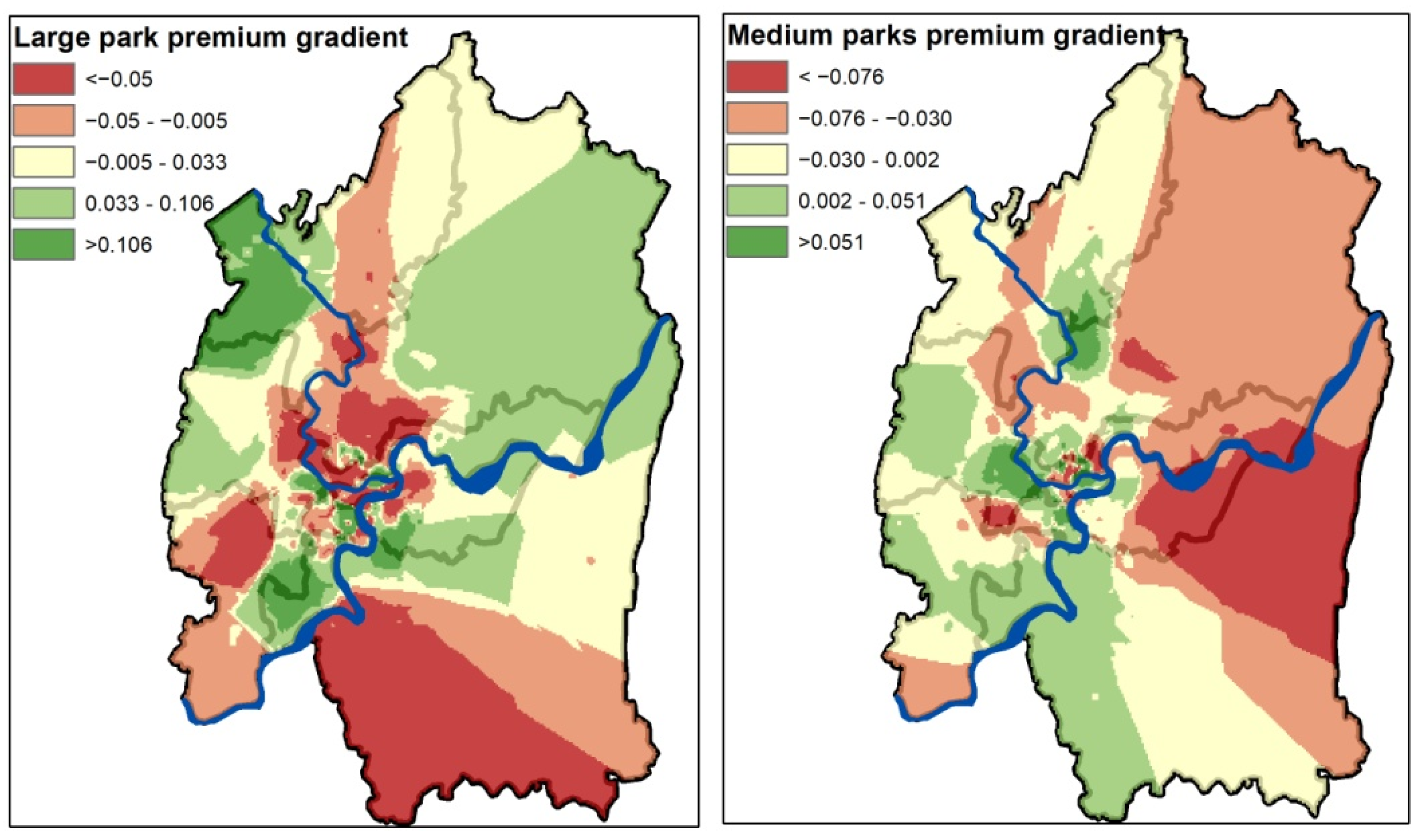

4.2.1. The Result of GWR

4.2.2. Housing Affordability Differences Due to Park Premiums

4.3. Phase III: Typical Case Investigation

4.3.1. The Selection of Typical Parks

4.3.2. Differences of Gentrification Indicators in Typical Community Samples

4.3.3. Residents’ Perceptions and Attitudes towards Green Gentrification

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, Y.; Zhao, R. Research on the Development of Urban Parks Based on the Perception of Tourists: A Case Study of Taihu Park in Beijing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. The role of the proximate principle in the emergence of urban parks in the United Kingdom and in the United States. Leis. Stud. 2007, 26, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, K.A.; Lewis, T.L. Green Gentrification: Urban Sustainability and the Struggle for Environmental Justice; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooling, S. Ecological gentrification: A research agenda exploring justice in the city. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 621–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearsall, H. From brown to green? Assessing social vulnerability to environmental gentrification in New York City. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2010, 28, 872–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Urban Plan 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sister, C.; Wolch, J.; Wilson, J. Got green? Addressing environmental justice in park provision. GeoJournal 2010, 75, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isabelle, A. From Toxic Sites to Parks as (Green) LULUs? New Challenges of Inequity, Privilege, Gentrification, and Exclusion for Urban Environmental Justice. J. Plan. Lit. 2016, 31, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immergluck, D. Large redevelopment initiatives, housing values and gentrification: The case of the Atlanta Beltline. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1723–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Curran, W.; Hamilton, T. Just green enough: Contesting environmental gentrification in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Local Environ. 2012, 17, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Joo, S.; Han, S.; Park, C. Mapping the distribution pattern of gentrification near urban parks in the case of Gyeongui Line Forest Park, Seoul, Korea. Sustainability 2017, 9, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rigolon, A.; Németh, J. Green gentrification or ‘just green enough’: Do park location, size and function affect whether a place gentrifies or not? Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearsall, H.; Eller, J.K. Locating the green space paradox: A study of gentrification and public green space accessibility in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Urban Plan 2020, 195, 103708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, K. Parks for profit: The high line, growth machines, and the uneven development of urban public spaces. City Community 2014, 13, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checker, M. Wiped out by the “greenwave”: Environmental gentrification and the paradoxical politics of urban sustainability. City Soc. 2011, 23, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Masip, L.; Pearsall, H. Assessing green gentrification in historically disenfranchised neighborhoods: A longitudinal and spatial analysis of Barcelona. Urban Geogr. 2017, 39, 458–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, H.V.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Connolly, J.J.; Anguelovski, I. Determining the health benefits of green space: Does gentrification matter? Health Place 2019, 57, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H. Rail-transit-induced gentrification and the affordability paradox of TOD. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 63, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J. The social construction of a gentrifying neighborhood: Reifying and redefining identity and boundaries in inequality. Urban Aff. Rev. 2016, 52, 98–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, K.J.; Richards, M. Eco-gentrification and who benefits from urban green amenities: NYC’s high Line. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 204, 103900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Byrne, J.; Xu, T.; Wang, S.; Wu, J. Can smaller parks limit green gentrification? Insights from Hangzhou, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 59, 127009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, C.; Oosterlynck, S.; Bradt, L. Livable streets? Green gentrification and the displacement of longtime residents in Ghent, Belgium. Urban Geography 2020, 41, 550–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, T. Temporal and spatial effects of a ‘Shan Shui’ landscape on housing price: A case study of Chongqing, China. Habitat Int. 2019, 94, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, L. Spatial effect of river landscape on housing price: An empirical study on the Grand Canal in Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Assessing amenity effects of urban landscapes on housing price in Hangzhou, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, M.; Li, W.; Peng, J.; Huang, L. Impact of Urban Green Space on Residential Housing Prices: Case Study in Shenzhen. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2014, 141, 05014023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.S.; Zhang, R. Temporal-spatial impact effects of large-scale parks on residential prices: Exemplified by the Huangxing Park in Shanghai. Geogr. Res. 2010, 29, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhen, K.L. Capitalized effect and spatial heterogeneity of parks: Taking Chongqing for example. Urban Probl. 2019, 38, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Yang, W.; Luo, C. Effects of urban park environment on recreational jogging activity based on trajectory data: A case of Chongqing, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 67, 127443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Kabisch, S.; Haase, A.; Andersson, E.; Banzhaf, E.; Baró, F.; Brenck, M.; Fischer, L.K.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Kabisch, N.; et al. Greening cities—To be socially inclusive? About the alleged paradox of society and ecology in cities. Habitat Int. 2017, 64, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.D. Tracking and explaining neighborhood socioeconomic change in US metropolitan areas between 1990 and 2010. Hous. Policy Debate 2016, 26, 2–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Variable | Description | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Residential price | Average price of residential quarters (RMB/m2) | 12,753 | 4006 |

| Independent variable | ||||

| Distance to parks | Distance to large parks | Distance to the nearest large park (m) | 3108 | 1890 |

| Distance to medium parks | Distance to the nearest medium park (m) | 1501 | 1377 | |

| Distance to small parks | Distance to the nearest small park (m) | 1318 | 924 | |

| Control variables | ||||

| Building characteristics | Residence age | Year from when the residence community was built (year) | 13.26 | 6.39 |

| Elevator | 1 = With elevator, 0 = otherwise | 0.77 | 0.42 | |

| Neighborhood characteristics | Property fee | Property fee of the community (RMB/m2 per month) | 1.48 | 0.94 |

| Greening rate | Greening rate of the community (%) | 0.32 | 0.08 | |

| Location characteristics | Distance to CBD | Distance to the nearest central business district (m) | 8168 | 8980 |

| Distance to hospital | Distance to the nearest third-class hospital (m) | 5037 | 5358 | |

| Distance to river | Distance to Yangtze and Jialing rivers (m) | 3279 | 3268 | |

| Distance to subway | Distance to the nearest subway station (m) | 1173 | 2011 | |

| Distance to bus stop | Distance to the nearest bus stop (m) | 480 | 701 | |

| Category | Variable | Coefficient | t-Statistic | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant term | 10.986 *** | 147.471 | ||

| Distance to the park | Log Distance to large park | −0.034 *** | −6.851 | 1.222 |

| Log Distance to medium park | −0.007 * | −1.698 | 1.228 | |

| Log Distance to small park | −0.004 | −0.969 | 1.149 | |

| Building characteristics | Log residence age | −0.071 *** | −12.057 | 2.288 |

| elevator | 0.347 *** | 44.241 | 1.415 | |

| Neighborhood characteristics | Log property fee | 0.166 *** | 21.802 | 2.113 |

| Log greening rate | 0.047 *** | 4.682 | 1.067 | |

| Location characteristics | Log distance to CBD | −0.033 *** | −10.384 | 1.731 |

| Log distance to hospital | −0.052 *** | −14.596 | 1.765 | |

| Log distance to river | −0.023 *** | −7.658 | 1.476 | |

| Log distance to subway | −0.066 *** | −15.976 | 1.494 | |

| Log distance to bus stop | −0.001 | −0.313 | 1.275 | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.694 | Mean VIF | 1.519 |

| Variable | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log distance to large park | −0.684 | 0.823 | −0.001 | 0.102 |

| Log distance to medium park | −0.407 | 0.557 | −0.012 | 0.062 |

| Log distance to small park | −0.620 | 0.597 | −0.013 | 0.056 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.811 |

| Income Quintiles of Permanent Residents | Low Income | Lower–Middle Income | Middle Income | Upper–Middle Income | High Income |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual income (RMB/year) | 9660 | 17,195 | 26,023 | 39,251 | 71,467 |

| Differential | 7535 | 8828 | 13,228 | 32,216 | |

| Bear additional annual cost of housing for different levels (RMB/m2) | 342 | 401 | 600 | 1462 |

| Park Size and Premiums | Large Parks | Medium Parks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Premiums | Low Premiums | High Premiums | Low Premiums | |

| Percentage of parks | 22.64% | 26.42% | 14.13% | 38.04% |

| Average residential price | 17,162 | 14,715 | 13,567 | 12,821 |

| Regression coefficient | 0.143 *** | 0.024 (Insignificant) | 0.044 *** | 0.028 *** |

| Coefficient of semi-elasticity (%) | 14.3% | 2.4% | 4.4% | 2.8% |

| Marginal appreciation (RMB/m2) | 2454 | 353 | 597 | 359 |

| Park Size | Large Parks | Medium Parks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Park Premium Grade | High Premium | Low Premium | No Premium | High Premium | Low Premium | No Premium |

| Park name | Zhimushan Forest Park | Caiyun Lake National Wetland Park | Shuanglong Lake Park | Mu Xian Lake Wetland Park | Rong Qiao Park | Smiley Park |

| Sample number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Park area (ha) | 287 | 136 | 32 | 12 | 11 | 9.5 |

| Number of residential communities within 1 km (pcs) | 9 | 17 | 11 | 20 | 17 | 15 |

| Park premium on average | −0.08 | −0.03 | None | −0.08 | −0.03 | None |

| Average price of residential community (RMB/m2) | 24,011 (2167) | 13,491 (2049) | 9299 (2395) | 14,924 (4095) | 16,064 (5128) | 7592 (1732) |

| Average age of residential community (year) | 4(1) | 12(5) | 16(5) | 10(4) | 11(6) | 15(5) |

| Sample Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Average of the Central Urban Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age distribution | |||||||

| Ages 18–35 | 21% | 23% | 19% | 29% | 23% | 19% | 24% |

| Ages 35–60 | 57% | 47% | 42% | 45% | 53% | 41% | 47% |

| Ages 60 and above | 22% | 30% | 39% | 26% | 24% | 41% | 29% |

| Educational level | |||||||

| College and above | 43% | 37% | 28% | 40% | 48% | 25% | 35% |

| High school | 19% | 24% | 23% | 22% | 21% | 22% | 21% |

| Junior high school and below | 36% | 39% | 48% | 39% | 30% | 53% | 44% |

| Professional status | |||||||

| Managers of enterprises and institutions | 9% | 3% | 0% | 5% | 6% | 0% | 2% |

| Professional, technical, clerical staff | 40% | 20% | 9% | 31% | 36% | 11% | 13% |

| Service workers, general workers, etc. | 17% | 41% | 47% | 29% | 21% | 47% | 46% |

| Non-economically active persons | 33% | 37% | 44% | 35% | 36% | 42% | 38% |

| Payable income per capita | |||||||

| More than 80 k | 33% | 19% | 6% | 25% | 30% | 5% | |

| 60 k–80 k | 28% | 25% | 16% | 31% | 33% | 13% | |

| 40 k–60 k | 19% | 24% | 30% | 25% | 18% | 34% | |

| 20 k–40 k | 16% | 24% | 31% | 14% | 14% | 30% | |

| ≤20 k | 3% | 9% | 17% | 6% | 5% | 19% |

| Sample Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition of parks to improve quality of life | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| Recognition of residential price increases by parks | 4.1 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.4 |

| Recognition of parks leading to gentrification | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| Discriminated against by the residents of the surrounding high-end houses | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Concerns about being relocated due to parks | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 2.1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; He, S.; Ma, W. Does Park Size Affect Green Gentrification? Insights from Chongqing, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169916

Wang B, He S, Ma W. Does Park Size Affect Green Gentrification? Insights from Chongqing, China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):9916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169916

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Bo, Shoukui He, and Weiwen Ma. 2022. "Does Park Size Affect Green Gentrification? Insights from Chongqing, China" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 9916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169916

APA StyleWang, B., He, S., & Ma, W. (2022). Does Park Size Affect Green Gentrification? Insights from Chongqing, China. Sustainability, 14(16), 9916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169916