The Mediating Role of Safety Climate in the Relationship between Transformational Safety Leadership and Safe Behavior—The Case of Two Companies in Turkey and Romania

Abstract

:1. Introduction

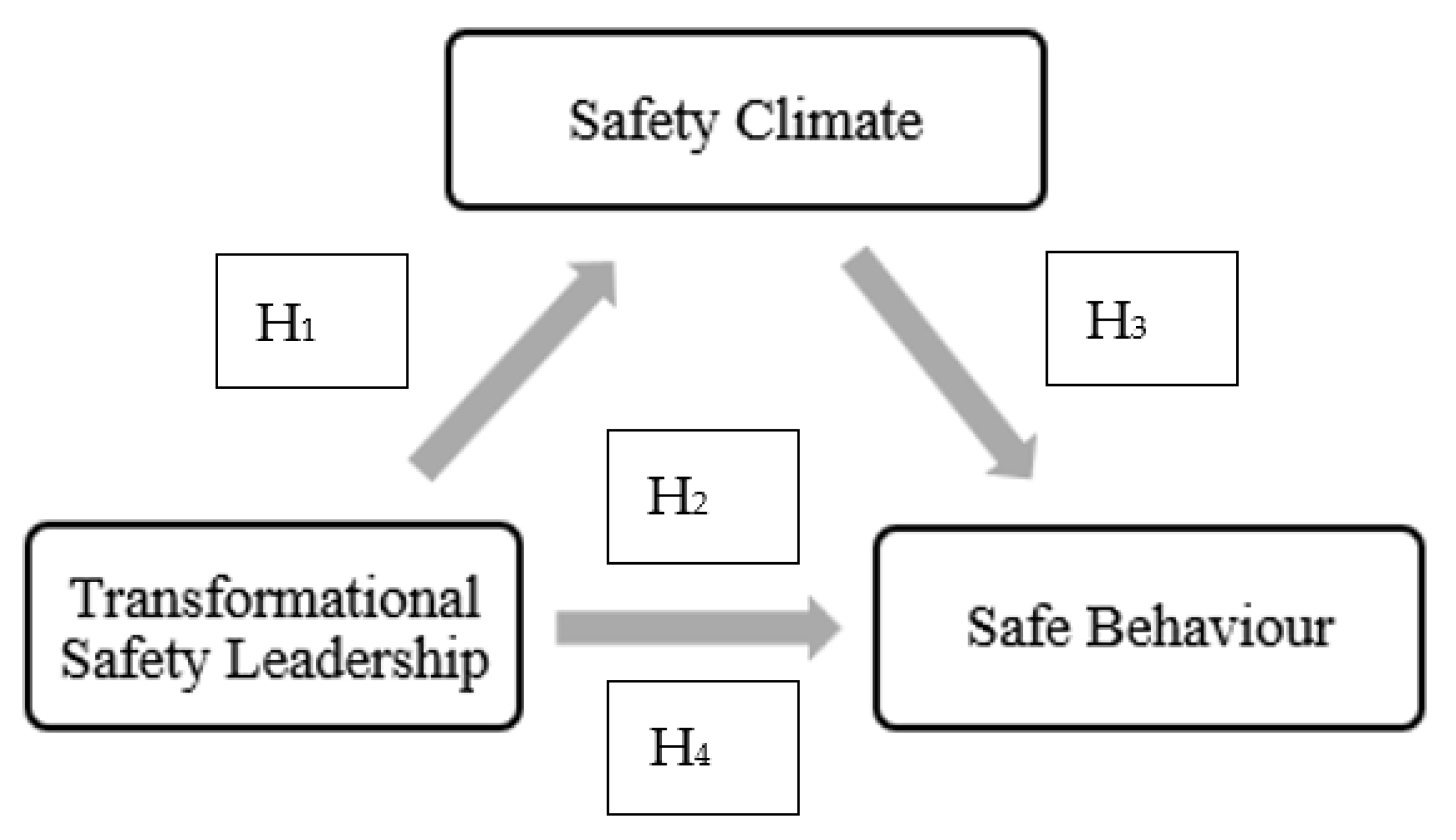

2. Conceptual Framework and Research Hypotheses

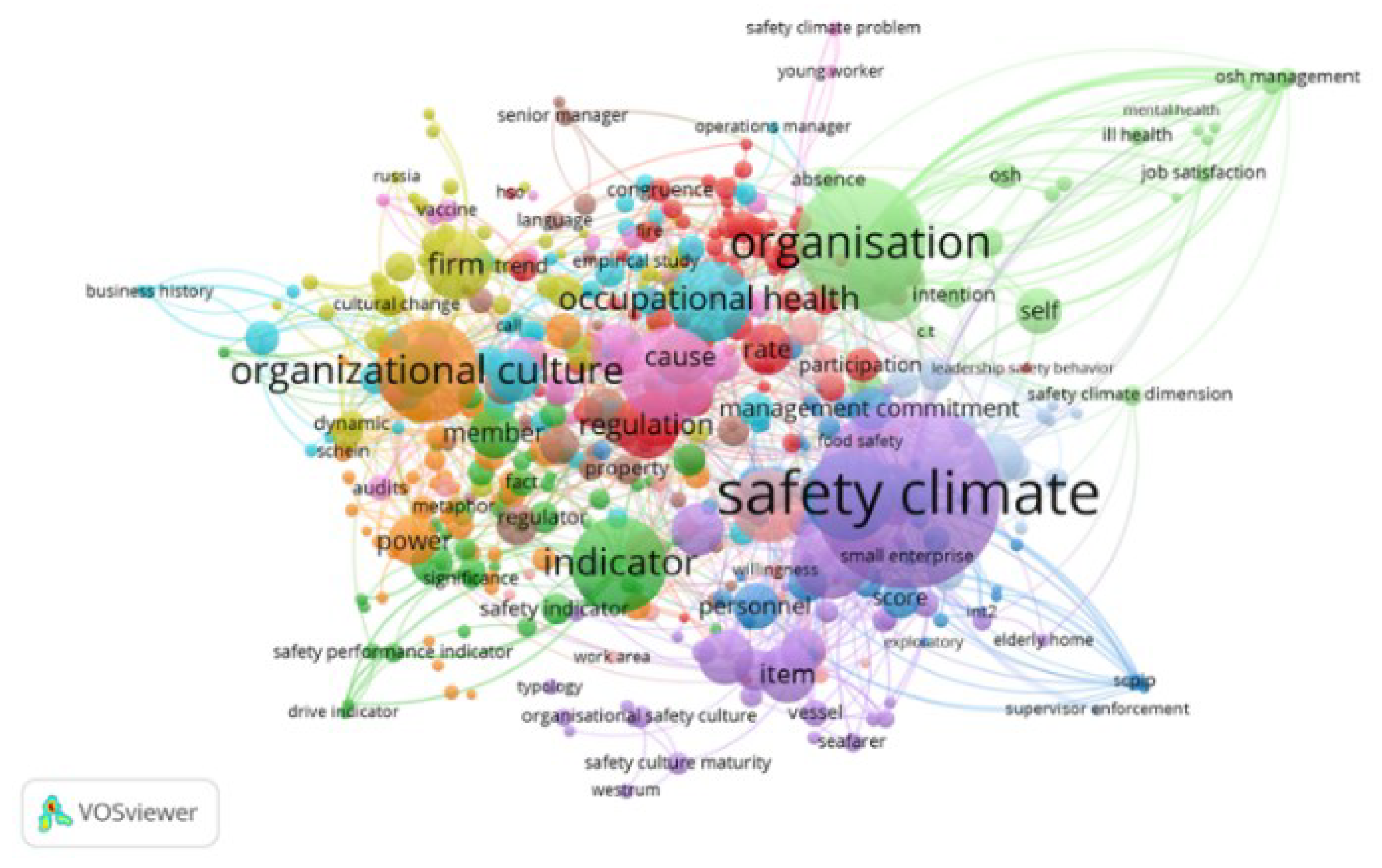

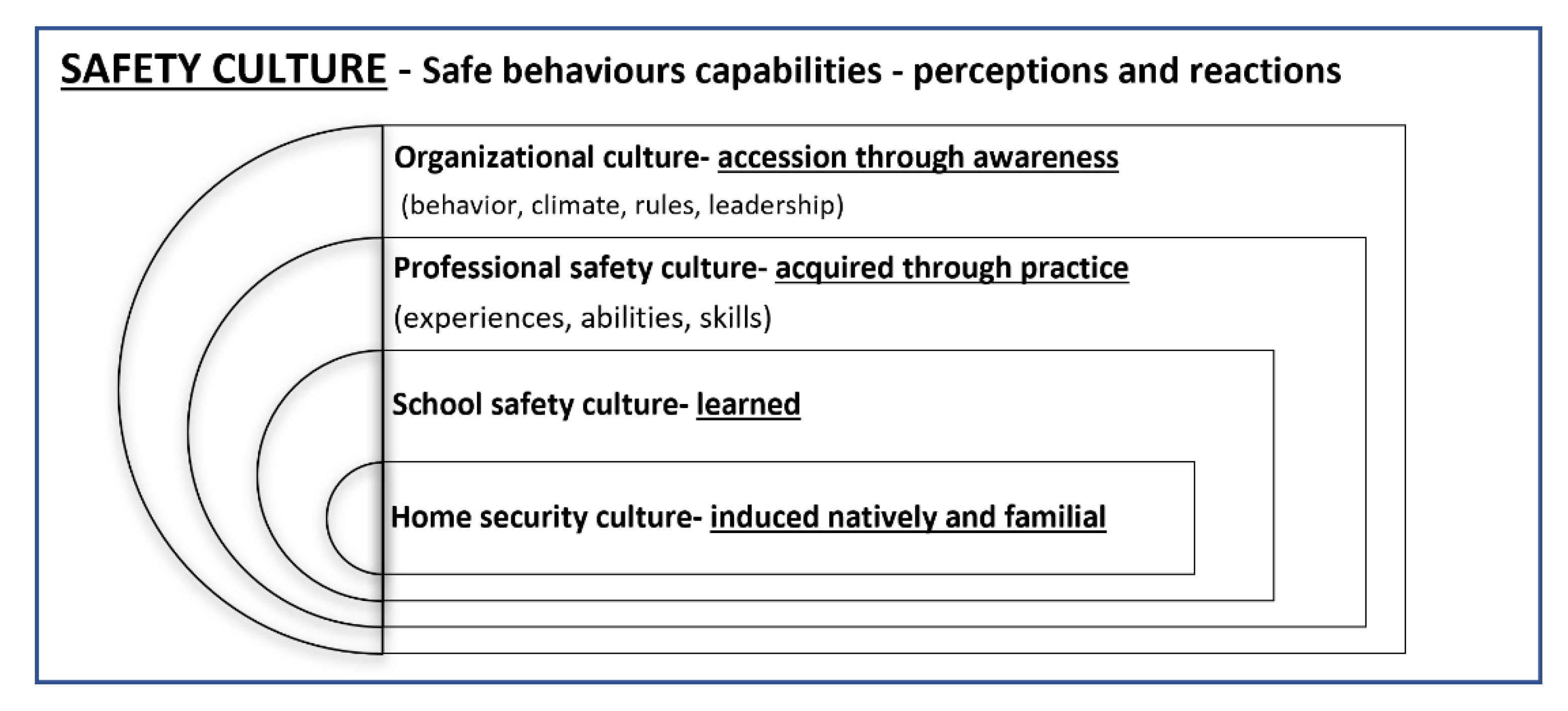

2.1. Safety Culture, Safety Climate, Safety Leadership Measurement

2.2. Safety Leadership and Transformational Safety Leadership

2.3. Transformational Safety Leadesrhip and Safety Climate

2.4. Transformational Safety Leadership and Safe Behavior

2.5. Safety Climate and Safe Behaviour

2.6. Mediation Role of Safety Climate in the Relationship between Transformational Safety Leadership and Safe Behaviour

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Sample

3.2. Data Collection Tools

3.3. Data Analysis

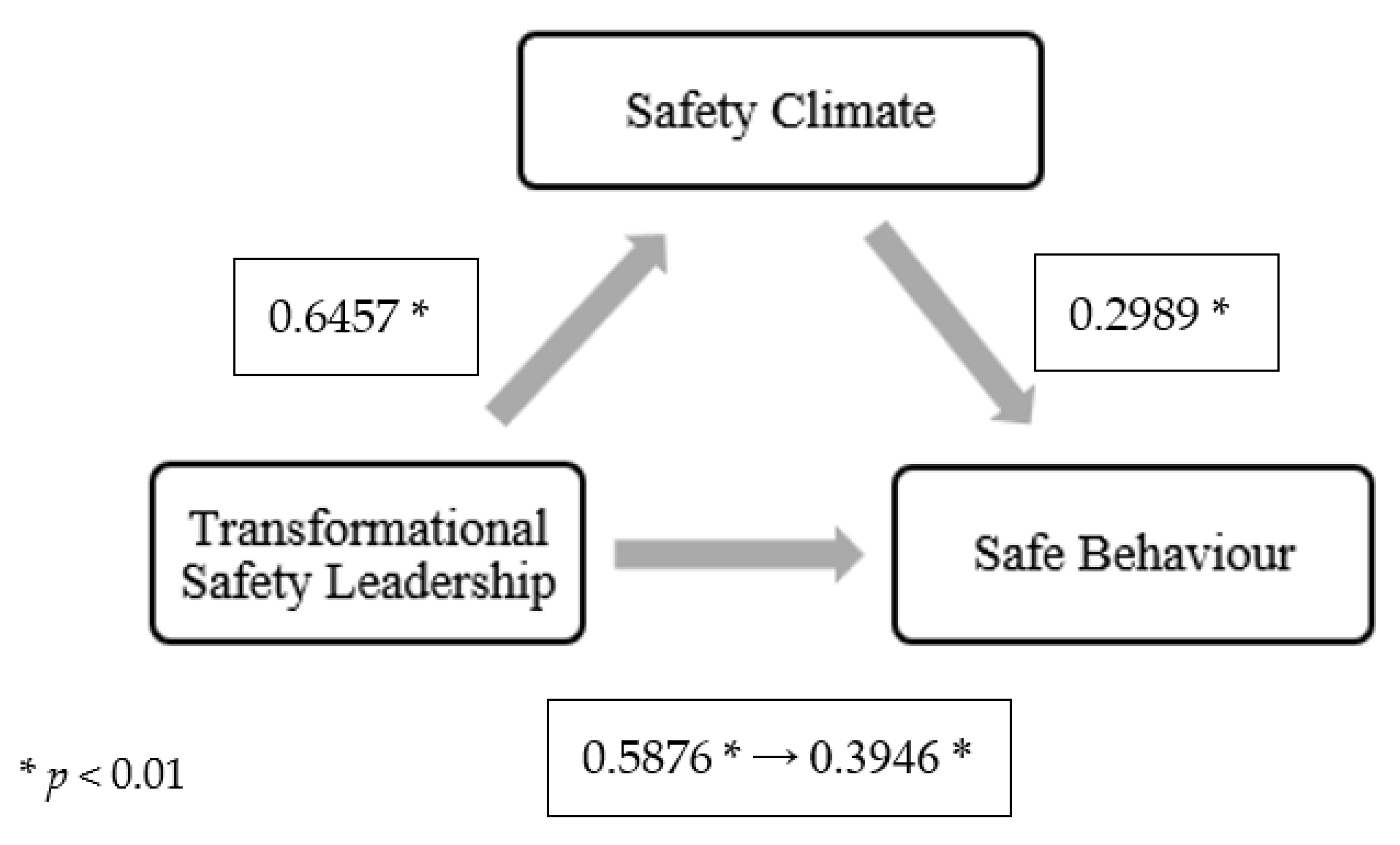

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Transformational Leadership Scale |

|---|

| 1. Express satisfaction when I perform my job safely. |

| 2. Makes sure that we receive appropriate rewards for achieving safety targets on the job. |

| 3. Provides continuous encouragement to do our jobs more safely. |

| 4. Shows determination to maintain a safe work environment. |

| 5. Suggests new ways of doing our jobs more safely. |

| 6. Encourages me to express my ideas and opinion about safety at work. |

| 7. Talks about his/her values and beliefs of the importance of safety. |

| 8. Behaves in a way that displays a commitment to a safe workplace. |

| 9. Spends time showing me the safest way to do things at work. |

| 10. Would listen to my concerns about safety on the job. |

| Safety Climate Scale |

| 1. New employees learn quickly that they are expected to follow good health and safety practices. |

| 2. Employees are told when they do not follow good health and safety practices. |

| 3. Workers and management work together to ensure the safest possible conditions. |

| 4. There are no major shortcuts taken when worker health and safety are at stake. |

| 5. The health and safety of workers is a high priority with management where I work. |

| 6. I feel free to report safety problems where I work. |

| Safety Behaviour Scale |

| 1. I use all the necessary safety equipment to do my job. |

| 2. I use the correct safety procedures for carrying out my job. |

| 3. I ensure the highest levels of safety when I carry out my job. |

| 4. I promote the safety program within the organization. |

| 5. I put in extra effort to improve the safety of the workplace. |

| 6. I voluntarily carry out tasks or activities that help to improve workplace safety. |

References

- International Labour Organization. The Enormous Burden of Poor Working Conditions. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/moscow/areas-of-work/occupational-safety-and-health/WCMS_249278/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- SGK. Sosyal Güvenlik Kurumu İstatistik Yıllıkları. Available online: http://www.sgk.gov.tr/wps/portal/sgk/tr/kurumsal/istatistik/sgk_istatistik_yilliklari (accessed on 13 October 2021).

- Şen, M.; Dursun, S.; Murat, G. Work accidents in Turkey: An evaluation in the context of The European Union countries. Int. J. Soc. Res. 2018, 9, 1167–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Ceylan, H. Facts on Safety at Work for Turkey. J. Multidiscip. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2015, 2, 3159–3199. [Google Scholar]

- ILO-STAT Statistics on Safety and Health at Work. 2016. Available online: https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/ (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- SKG (Social Security Agency). 2020 Statistical Information, Form 3.1.5 (4a). Available online: https://www.sgk.gov.tr/Istatistik/Yillik/fcd5e59b-6af9-4d90-a451-ee7500eb1cb4/ (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- Labor Inspectorate. Accidents at Work 2020. Available online: https://www.inspectiamuncii.ro/statistici-accidente-de-munca/-/asset_publisher/FpOPIUxxmReZ/content/situatii-accidente-de-munca-9-luni-2020?inheritRedirect=false&redirect=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.inspectiamuncii.ro%2Fstatistici-accidente-de-munca%3Fp_p_id%3D101_INSTANCE_FpOPIUxxmReZ%26p_p_lifecycle%3D0%26p_p_state%3Dnormal%26p_p_mode%3Dview%26p_p_col_id%3Dcolumn-2%26p_p_col_count%3D1 (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- Turkish Statistical Institute. Labor Force Statistics, November 2020. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Labour-Force-Statistics-November-2020-37480&dil=2#:~:text=Employment%20rate%20realized%20as%2042.9,with%202.7%20percentage%20point%20decrease (accessed on 23 May 2022).

- National Institute of Statistics. Labor Force Balance. 2020, p. 27. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/sites/default/files/field/publicatii/balanta_fortei_de_munca_la_1_ianuarie_2020.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Christian, M.S.; Bradley, J.C.; Wallace, J.C.; Burke, M.J. Workplace safety: A meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1103–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhry, R.M.; Fang, D. Why operatives engage in unsafe work behavior: Investigating factors on construction sites. Saf. Sci. 2008, 46, 566–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wu, C.; Wang, B.; Ouyang, Q.; Lin, H. An unsafe behaviour formation mechanism based on risk perception. Hum. Factors Manag. 2018, 29, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toderi, S.; Balducci, C.; Gaggia, A. Safety-specific transformational and passive leadership styles: A contribution to their measurement. TPM 2016, 23, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Hu, X. How leaders differentially motivate safety compliance and safety participation: The role of monitoring, inspiring and learning. Saf. Sci. 2013, 60, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A. Safety climate and safety behaviour. Aust. J. Manag. 2002, 27, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.M.; Boix, P.; Kanosa, C. Why do workers behave unsafely at work? Determinants of safe work practices in industrial workers. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 61, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.M.; Phillips, R.A. Exploratory analysis of the safety climate and safety behaviour relationship. J. Saf. Res. 2004, 35, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.; Hon, C.K.; Chan, A.; Wong, F.; Javed, A.A. Relationships among safety climate, safety behavior and safety outcomes for ethnic minority construction workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Huang, Y.H.; Sinclair, R.R.; Cheug, J.H. Outcomes of safety climate in trucking: A longitudinal framework. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; McCabe, B.; Jia, G.; Sun, J. Effects of safety climate and safety behavior on safety outcomes between supervisors and construction workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04019092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücebilgiç, H. A Proposed Model of Safety Climate Contributing Factors and Consequences. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sadullah, Ö.; Kanten, S. A research on the effect of organizational safety climate upon the safe behaviors. Ege Akad. Bakış. 2009, 9, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorulmaz, M.; Büyük, N.; Birgün, S. Tersane işletmelerinde örgütsel güvenlik ikliminin incelenmesi. J. Acad. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2016, 46, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ören, K.; Er, M. Güvenlik ikliminin güvenlik performansına etkisi. Emek ve Toplum 2016, 5, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgiç, R.; Bulazer, M.B.; Bürümlü, E.; Öztürk, İ.; Taşçıoğlu, C. The effects of leadership on safety outcomes: The mediating roles of trust and safety climate. Int. J. OSH 2018, 6, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akdeniz, B. Liderlik tarzları ve güvenlik liderliği: İnsan hatasından kaynaklanan iş kazalarını önlemede bir çözüm önerisi. Dumlupınar Üniversitesi Sos. Bilimler Derg. 2019, 61, 132–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zohar, D. The effects of leadership dimensions, safety climate and assigned priorities on minor injuries in work groups. J. Org. Behav. 2002, 23, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.C.; Chen, C.H.; Li, C.C. A correlation among safety leadership, safety climate and safety performance. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2008, 21, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockholm Center for Freedom. Turkey Had the Highest Number of Occupational Fatalities in Europe in 2018: Report. Available online: https://stockholmcf.org/turkey-had-the-highest-number-of-occupational-fatalities-in-europe-in-2018-report/ (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Van Nunen, K.; Li, J.; Reniers, G.; Ponnet, K. Bibliometric analysis of safety culture research. Saf. Sci. 2018, 108, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Wiegmann, D.; Thaden, T.; Sharma, G.; Mitchell, A. Safety Culture: A Concept in Chaos? Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2002, 46, 1404–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gadd, S.; Collins, A.M. Safety Culture: A review of the literature. Health Saf. Lab. 2002, 44, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, T.; De Cieri, H. A Review and Evaluation of Safety Culture and Safety Climate Measurement Tools. 2015. Available online: https://research.iscrr.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/533581/review-and-evaluation-of-safety-culture-and-safety-climate-measurement-tools.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Guldenmund, F.W. The nature of safety culture: A review of theory and research. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 215–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldenmund, F.W. The use of questionnaires in safety culture research—An evaluation. Saf. Sci. 2007, 45, 723–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.; Flin, R. Safety culture: Philosopher’s stone or man of straw? Stress 1998, 12, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonsen, S. Safety culture assessment: A mission impossible? J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2009, 17, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldenmund, F.W. (Mis)understanding Safety Culture and Its Relationship to Safety Management. Risk Anal. 2010, 30, 1466–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, F.; Ferguson, M.; Hann, L. Developing Teacher Leaders: How Teacher Leadership Enhances School Success; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4129-6374-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M.D. Navigating the Safety Culture Construct: A Review of the Evidence. 2016. Available online: https://www.behavioral-safety.com/articles/safety_culture_review.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Cooper, D. Effective safety leadership: Understanding types and styles that improve safety performance. Prof. Saf. 2015, 60, 9–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, J.E.; Kelloway, E.K. Safety leadership: A longitudinal study of the effects of transformational leadership on safety outcomes. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barling, J.; Loughlin, C.; Kelloway, E.K. Development and test of a model linking safety-specific transformational leadership and occupational safety. J. App. Psychol. 2002, 87, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Full Range Leadership Development: Manual for the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire; Mindgarden: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Improving Organizational Effectiveness through Transformational Leadership; Sage Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 0-8039-5235-X. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, J.E.; Kelloway, E.K.; Teed, M. Inconsistent style of leadership as a predictor of safety behaviour. Work Stress 2011, 25, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D. Safety climate in industrial organizations: Theoretical and applied implications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1980, 65, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A.; Hart, P.M. The impact of organizational climate on safety climate and individual behaviour. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Córcoles, M.; Gracia, F.; Tomás, I.; Peiró, J. Leadership and employees’ perceived safety behaviours in a nuclear power plant: A structural equation model. Saf. Sci. 2011, 49, 1118–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E.K.; Mullen, J.; Francis, L. Divergent effects of transformational and passive leadership on employee safety. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuesheng, D.; Wenbiao, S. Research on the relationship between safety leadership and safety climate in coalmines. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Symposium on Safety Science and Technology, Procedia Engineering, Nanjing, China, 23–26 October 2012; pp. 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, T.D.; Eldridge, F.; Dejoy, D.M. Safety-specific transformational and passive leadership influences on firefighter safety climate perceptions and safety behavior outcomes. Saf. Sci. 2016, 86, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Ju, C.; Koh, T.Y.; Rowlinson, S.; Bridge, A.J. The impact of transformational leadership on safety climate and individual safety behavior on construction sites. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lingard, H.; Wakefield, R.; Cashin, P. The development and testing of a hierarchical measure of project OHS performance. Eng. Constr. Architect. Manag. 2011, 18, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yule, S. Senior Management Influence on Safety Performance in the UK and US Energy Sectors. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Andrei, D.; Grech, M.R.; Griffin, M.; Neal, A. Assessing the determinants of safety culture in the maritime industry. Int. J. Maritime Eng. 2020, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tholén, S.L.; Pousette, A.; Törner, M. Causal relations between psychosocial conditions, safety climate and safety behaviour—A multi-level investigation. Saf. Sci. 2013, 55, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, C.S.; Yang, C.S. Safety leadership and safety behavior in container terminal operations. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D.A.; Morgeson, F.P. Safety related behavior as a social exchange: The role of perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Probst, T.M. Transformational and passive leadership as cross-level moderators of the relationships between safety knowledge, safety motivation and safety participation. J. Saf. Res. 2016, 57, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Yang, D.; Liu, S.; Nkrumah, E.N.K. The Effect of Safety Leadership on Safety Participation of Employee: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 827694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S. The relationship between safety climate and safety performance: A meta-analytic review. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A. Perceptions of safety at work: A framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.S.; Yang, C.S. Safety climate and safety behavior in the passenger ferry context. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froko, F.; Umar, F. The impact of safety climate in safety performance in a gold mining company in Ghana. Int. J. Manag. Excell. 2015, 5, 556–566. [Google Scholar]

- Jusoh, H.M.; Panatik, S.A. The effects of safety climate on safety performance: An evidence in a Malaysian-based electric electronic and manufacturing plant. Sains Hum. 2016, 8, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saedi, A.M.; Majid, A.A. Relationships between safety climate and safety participation in the petroleum industry: A structural equation modeling approach. Saf. Sci. 2020, 121, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzoli, A.; Probst, T.M. COVID-19 moral disengagement and prevention behaviors: The impact of perceived workplace COVID-19 safety climate and employee job insecurity. Saf. Sci. 2022, 150, 105703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, S. Safety leadership: A meta-analytic review of transformational and transactional leadership styles as antecedents of safety behaviors. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 86, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boatca, M.E.; Draghici, A.; Gaureanu, A. Home ergonomics–lessons learned. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Manufacturing Science and Education (MSE 2021), Sibiu, Romania, 2–4 June 2021; Volume 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arief, Z.; Eliyana, A.; Anggraini, R.D.; Sari, P.A. The effect of safety-specific transformational leadership and safety-specific passive leadership on safety behaviors mediated by safety climate. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adi, E.N.; Eliyana, A.; Hamidah Mardiana, A.T. Safety leadership and safety behavior in MRO business: Moderating role of safety climate in garuda maintenance facility Indonesia. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Valencia, J.C.; Jimenez-Jimenez, D.; Sanz-Valle, R. Organizational culture and radical innovation: Does innovative behavior mediate this relationship? Creat. Innov. Manag. 2017, 26, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, S.; Aytac, S. The effect of safety culture on safety in an organizational structure: A case study in Turkey. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Human Factors in Organisational Design and Management (ODAM 2011), Grahamstown, South Africa, 4–6 April 2011; pp. 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton, S.J. Population Research: Convenience Sampling Strategies. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2021, 36, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, S.E.; Murphy, L.R. A short scale for measuring safety climate. Saf. Sci. 2008, 46, 1047–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatuna, I.; Başol, O. Job satisfaction of part-time vs. full-time workers in Turkey: The effect of income and work status satisfaction. Int. J. Value Chain Manag. 2017, 8, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, S.; Başol, O. Müşteri sözlü saldırganlığının çalışanların işten ayrılma niyeti üzerine etkisi: Duygusal tükenmenin aracılık rolü. Sos. Siyaset Konf. Derg. 2020, 78, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ardura, I.; Meseguer-Artola, A. Editorial: How to prevent, detect and control common method variance in electronic commerce research. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 15, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Ting, H. Guest editorial. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2021, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serinikli, N. Çalışanların örgütsel destek algılarının iş tatminlerine etkisinde iş stresinin aracılık rolü. Gümüşhane Üniversitesi Sos. Bilimler Enst. Elektron. Derg. 2019, 10, 585–597. [Google Scholar]

- Manjula, N.H.C.; De Silva, N. Factors Influencing Safety Behaviours of Construction Workers. In Proceedings of the Third World Construction Symposium 2014: Sustainability and Development in Built Environment, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 20–22 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom, J.T. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling: A Comprehensive Introduction, 1st ed.; Multivariate Applications Series; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2019, 72, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coelho, D.A.; Matias, J.C.; Filipe, J.N. The Benefits of Occupational Health and Safety Standards. In Handbook of Standards and Guidelines in Human Factors and Ergonomics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 541–556. [Google Scholar]

- Naji, G.M.A.; Isha, A.S.N.; Mohyaldinn, M.E.; Leka, S.; Saleem, M.S.; Rahman, S.M.N.B.S.A.; Alzoraiki, M. Impact of safety culture on safety performance; mediating role of psychosocial hazard: An integrated modelling approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. Detecting multicollinearity in regression analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2020, 8, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-J.; Jeong, B.-Y. Older Male Construction Workers and Sustainability: Work-Related Risk Factors and Health Problems. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvino, A.R.; Manco, P.; Garzillo, E.M.; Monaco, M.G.L.; Greco, A.; Gerbino, S.; Caputo, F.; Macchiaroli, R.; Lamberti, M. Assessing Risks Awareness in Operating Rooms among Post-Graduate Students: A Pilot Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucci, N.; Traversini, V.; Giorgi, G.; Garzaro, G.; Fiz-Perez, J.; Campagna, M.; Rapisarda, V.; Tommasi, E.; Montalti, M.; Arcangeli, G. Migrant Workers and Physical Health: An Umbrella Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cirjaliu, B.; Draghici, A. Ergonomics Issues in Lean Manufacturing. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 221, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Demographic Characteristic | Number | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Turkish | 186 | 64.8 |

| Romanian | 101 | 35.2 | |

| Education | Primary school | 140 | 48.7 |

| High school | 109 | 38.0 | |

| University | 38 | 13.2 | |

| Work experience | Junior (0–3 years) | 100 | 34.8 |

| Mature (4–10 years) | 144 | 50.2 | |

| Senior (11+ years) | 43 | 15 | |

| Age | 18 to 30 years | 94 | 32.8 |

| 31 to 40 years | 106 | 36.9 | |

| 41+ years | 87 | 30.3 | |

| Variables | Nationality | Mean ± SD | Z 1 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety climate | Turkish | 3.67 ± 1.11 | −0.574 | 0.566 |

| Romanian | 3.74 ± 0.84 | |||

| Transformational safety leadership | Turkish | 3.45 ± 1.10 | −0.949 | 0.343 |

| Romanian | 3.64 ± 0.80 | |||

| Safe behaviour | Turkish | 3.76 ± 0.99 | −0.481 | 0.631 |

| Romanian | 3.87 ± 0.82 |

| Variables | Number of Items | Mean ± SD | Correlations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | TSL | |||

| Safety climate (SC) | 6 | 3.70 ± 1.02 | - | |

| Transformational safety leadership (TSL) | 10 | 3.52 ± 1.01 | 0.716 1 | - |

| Safe behaviour (SB) | 6 | 3.80 ± 0.94 | 0.683 1 | 0.669 1 |

| Indirect Effect Estimation | Indirect Effect Coefficient | Standard Error | Lower 95% Confidence Interval | Upper 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety climate | 0.1930 | 0.0775 | 0.0825 | 0.3684 |

| Relationship | β | SE | t-Value | Hypothesis | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSL → SC | 0.6457 | 0.0462 | 13.97 | H1 | Supported |

| TSL → SB | 0.5876 | 0.0426 | 13.78 | H2 | Supported |

| SC → SB | 0.2989 | 0.0518 | 5.77 | H3 | Supported |

| TSL → SC → SB | 0.3946 | 0.0524 | 7.52 | H4 | Partially supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Draghici, A.; Dursun, S.; Bașol, O.; Boatca, M.E.; Gaureanu, A. The Mediating Role of Safety Climate in the Relationship between Transformational Safety Leadership and Safe Behavior—The Case of Two Companies in Turkey and Romania. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148464

Draghici A, Dursun S, Bașol O, Boatca ME, Gaureanu A. The Mediating Role of Safety Climate in the Relationship between Transformational Safety Leadership and Safe Behavior—The Case of Two Companies in Turkey and Romania. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148464

Chicago/Turabian StyleDraghici, Anca, Salih Dursun, Oğuz Bașol, Maria Elena Boatca, and Alin Gaureanu. 2022. "The Mediating Role of Safety Climate in the Relationship between Transformational Safety Leadership and Safe Behavior—The Case of Two Companies in Turkey and Romania" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148464

APA StyleDraghici, A., Dursun, S., Bașol, O., Boatca, M. E., & Gaureanu, A. (2022). The Mediating Role of Safety Climate in the Relationship between Transformational Safety Leadership and Safe Behavior—The Case of Two Companies in Turkey and Romania. Sustainability, 14(14), 8464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148464