A Game-Theory-Based Interaction Mechanism between Central and Local Governments on Financing Model Selection in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- This paper designs a game framework between the central and local governments by land price premium. It then compares the operation mechanism of local financing platforms and PPP models, which provides a new perspective for understanding the dependence of local economic development on land finance.

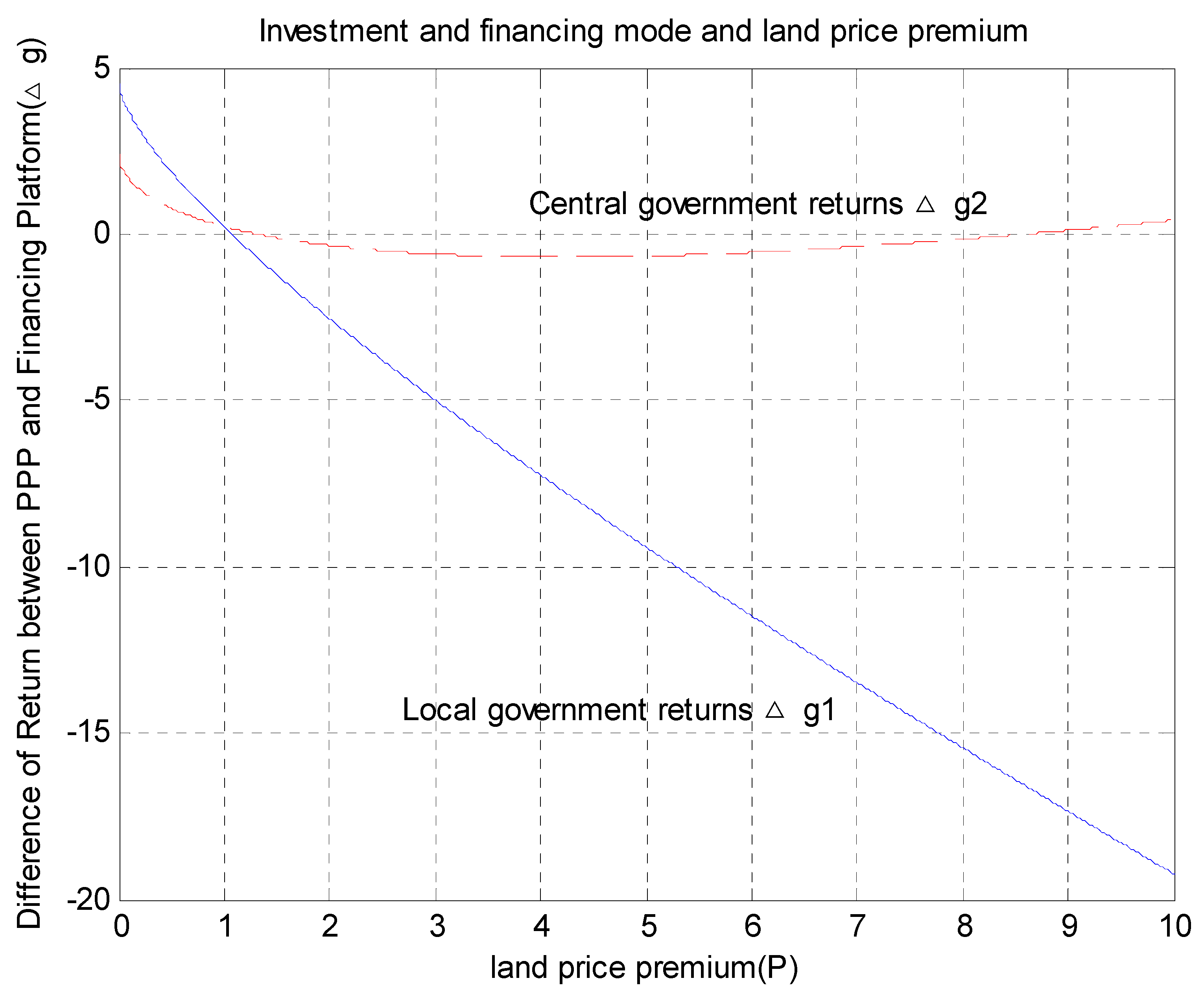

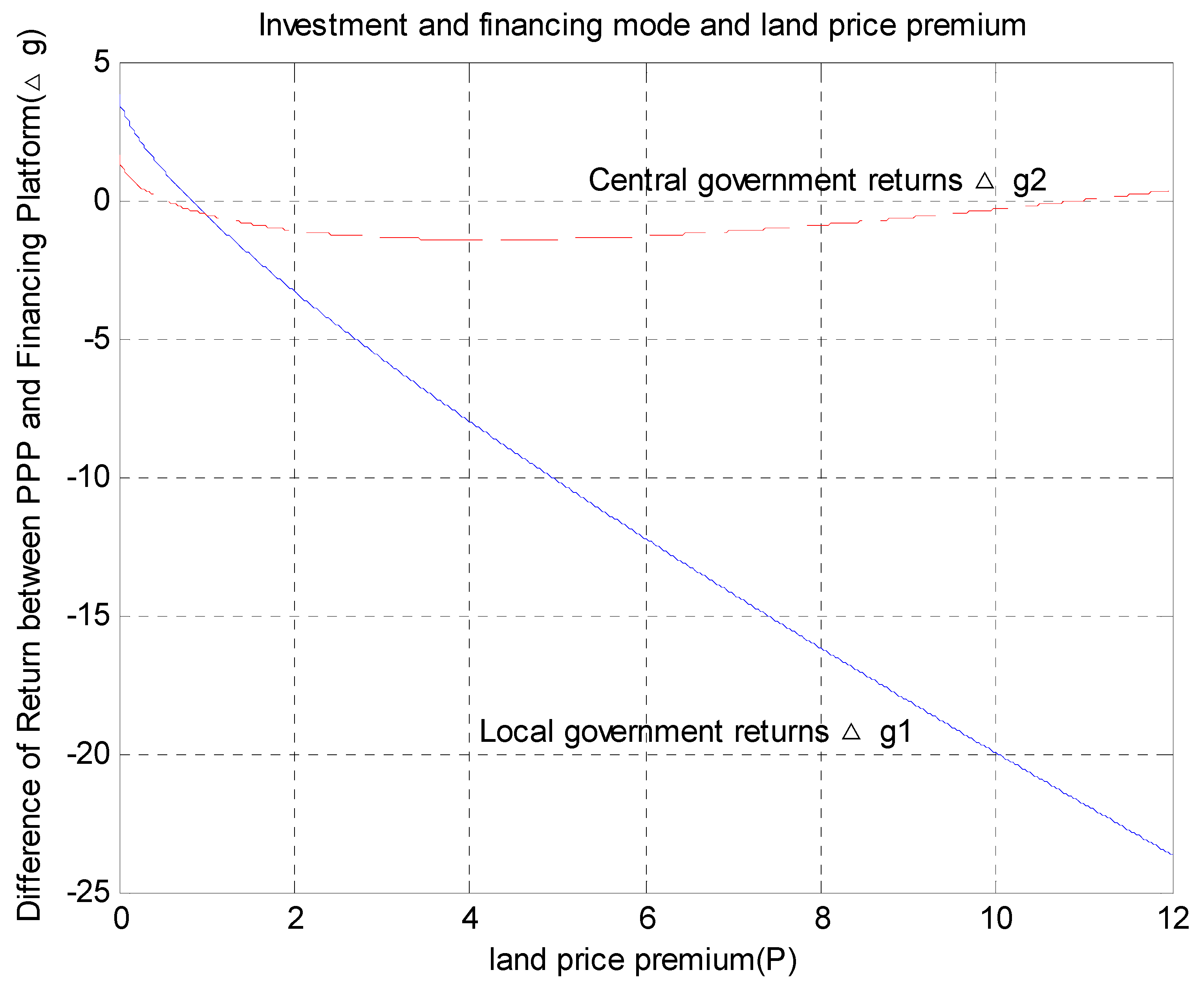

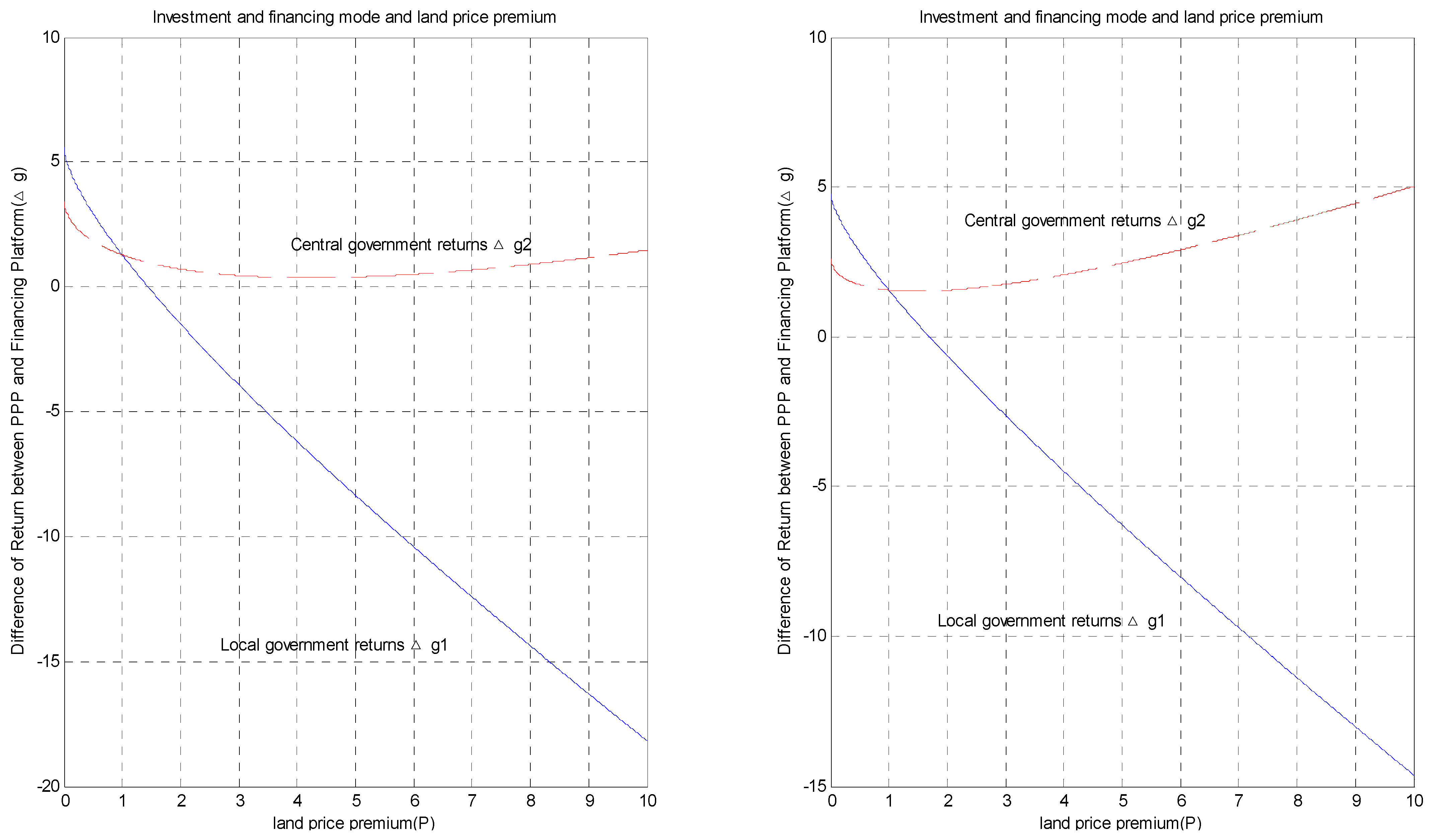

- The results of this paper enhance the understanding of the impact of land price premiums on local economic development. When the land price premium is not high, land finance plays a role in promoting economic development; when the land price premium is high, the model of land finance promoting economic development is not sustainable. The PPP model can moderately resolve the debt risk of local government financing platforms and alleviate the financial pressure on local governments.

- This paper utilizes the endogenous payment function and discusses the causes of debt risk and the governance of debt risk by comparing the proposed approach with the existing game literature. The numerical simulation of behavior decision making verified the proposed model.

2. Related Work

3. Theoretical Model of Investment and Financing

3.1. Traditional Financing Platform Model and Land Finance

3.2. PPP Model

4. Analysis of Government Decision Making

4.1. Government Decision-Making Model

4.2. Numerical Simulation Experiments

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Findings and Suggestions

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arsanjani, J.J.; Fibk, C.S.; Vaz, E. Development of a cellular automata model using open source technologies for monitoring urbanisation in the global south: The case of Maputo, Mozambique. Habitat Int. 2018, 71, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baoan, W. Actively promoted the use of PPP model to comprehensively improve the level of government public services. China Financ. 2014, 9, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Plekhanov, A. How Should Subnational Government Borrowing Be Regulated? Some Cross—Country Empirical Evidence. IMF Work. Pap. 2006, 53, 426–452. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P. Transformation, development and countermeasures of local investment and financing platforms under the new normal. Manag. World 2017, 8, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H. Legal countermeasures for local financing platform companies to withdraw from the market. Res. Soc. Chin. Charact. 2021, 6, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, N.; Chen, S.; Ma, H. Evolution of local financing platform debt risk—Based on the measurement of ‘implicit guarantee’ expectation. China Ind. Econ. 2021, 4, 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Research on investment and financing mode of urban infrastructure and public service facilities. Res. Financ. Probl. 2013, 4, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Liu, H.; Ma, X. Debt governance, maturity mismatch of local financing platforms and corporate performance—Based on the study of ‘43’. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L. Multidimensional Differences in the Distribution of PPP Projects in China and Their Causes. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Luo, L. Research on PPP model to Resolve Debt Risk of Local Financing Platform. Financ. Superv. 2016, 373, 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Guo, X. PPP modell and Local Government Financial Soft Constraints. Financ. Issues Res. 2021, 5, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, A. Financial Risks and Countermeasures of PPP Model. Master’s Thesis, Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, Nanchang, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Jiao, Y. The innovation of public policy to resolve the risk of local debt: The security model and its experience. China’s Adm. Manag. 2019, 4, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. Encouragement or containment: The dual logic of local government financing platform governance. Local Financ. Res. 2021, 5, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zuo, T. Game Analysis of Local Government Debt Risk Regulation. Beijing Soc. Sci. 2012, 5, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Tang, X. Local government debt risk evolution mechanism analysis-a game perspective based on network embedding. Soc. Sci. 2013, 1, 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Cao, H. Local government financing credit risk control: The central and local game. Econ. Res. Ref. 2010, 38, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Chen, G. The formation mechanism of Chinese local government debt under institutional arrangements and changes—A complete framework based on game analysis. J. Yunnan Univ. Financ. Econ. 2019, 35, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, W.; Ye, S. Evolution analysis of local government debt risk preference. Explor. Econ. Probl. 2014, 12, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Yang, J. Suggestions on Strengthening Local Government Debt Management in China—Based on the tripartite game analysis of the central government, local government and financial institutions. Innovation 2011, 5, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Gao, C. Based on the game perspective of China’s local government implicit debt alienation research. Econ. Dimens. 2020, 11, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Liu, X. Classified supervision of local government debt financing based on risk preference game analysis. J. Cent. Univ. Financ. Econ. 2016, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Avinash, D.; John, L. Political Power and the Credibility of Government Debt. J. Econ. Theory 2000, 1, 80–105. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher, B.; Esteves, R.P. Sovereign Debt: The Assessment. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2013, 3, 463–477. [Google Scholar]

- Rohan, P.; Wright Mark, L.J. On the Contribution of Game Theory to the Study of Sovereign Debt and Default. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2013, 4, 649–667. [Google Scholar]

- Inman, R. Transfers and Bailouts: Institutions for Enforcing Local Fiscal Displine. Const. Political Econ. 2001, 2, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.-G.; Zhao, X.; Gay, M.J.S. Public private partnership projects in Singapore: Factors, critical risks and preferred risk allocation from the perspective of contractors. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chan, A.P.C.; Feng, Y.; Duan, H.; Ke, Y. Critical review on PPP Research—A search from the Chinese and International Journals. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. The World Bank Annual Report 2014; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McCraw, T.K. TVA and the Power Fight, 1933–1939; Philadelphia, J.B., Ed.; Lippincott Company: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Caro, R. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York; Alfred a Knopf Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Eckel, C.C.; Vining, A.R. Elements of a theory of mixed enterprise. Scott. J. Political Econ. 1985, 32, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, T. Public–Private Partnerships: From Contested Concepts to Prevalent Practice. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2004, 70, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. New urbanization investment and financing mode selection and implementation path. Econ. Dimens. 2022, 3, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Lu, J.; Li, Y. Does the PPP modell improve the quality of new urbanization? Stat. Res. 2020, 37, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, X.; Cheng, L. The logic and thinking of PPP to prevent local government debt risk in China—From ‘behavioral sacrifice efficiency’ to ‘mechanism recovery efficiency’. Financ. Res. 2015, 8, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, J.; Pramudawardhani, D. Cross-country Comparisons of Key Drivers, Critical Success Factors and Risk Allocation for Public-private-Partnership Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1136–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Time-varying effects of urbanization on economic growth and carbon emissions. Tech. Econ. Manag. Res. 2022, 1, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Shi, H.; Lin, Y. Path Analysis of the Impact of Urbanization on Economic Growth—Based on the Study of the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration. Econ. Issues 2022, 4, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; Yuan, Y. An Empirical Study on the Impact of Green New Urbanization on Economic Growth. J. Shanghai Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 36, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, H. The impact mechanism of China’s urbanization on economic growth and its regional differ-ences-An empirical analysis based on provincial panel data. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2014, 36, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y. Local government behavior and the development of China’s market economy. Economists 1997, 1, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, G. Theoretical basis and motivation of local government investment and financing platform in China. Manag. World 2011, 3, 168–169. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Li, L. Theoretical analysis of local government financing platform borrowing. Financ. Res. 2013, 5, 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, H.; Tang, D.; Gu, J. Local government loan risk control for corporate operation. Financ. Res. 2005, 3, 158–168. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Sun, W.; Wu, J. ‘Land fortune, land fortune’—Research on investment and financing mode of urban construction with Chinese characteristics. Econ. Res. 2014, 8, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Liu, S.; Li, Q. Land system reform and national economic growth. Manag. World 2007, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; An, R. Correcting the alienation of PPP projects into local financing platforms and its legal path. Nanjing Soc. Sci. 2020, 390, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, W.; Yang, W. The application of PPP modell in the transformation and development of local government investment and financing plat-form. J. Tianjin Vocat. Coll. Commer. 2019, 7, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hongqing, J.; Hong, Y. The transformation strategy of financing platform under the background of PPP. Financ. Account. Newsl. 2017, 17, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, J. Research on Financing Risk Sharing of PPP Model in China. Master’s Thesis, Huaqiao University, Quanzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.; Yuan, J.; Han, Z. Research on investment and financing mode of China’s urbanization construction. Econ. Geogr. 2013, 33, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, G. The coordinated development of financing platform and PPP. China Financ. 2017, 8, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, O. Incomplete Contracts and Public Ownership: Remarks, and an Application to Public-Private Partnerships. Econ. J. 2003, 113, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.; Iossa, E. Building and managing facilities for public services. J. Public Econ. 2006, 90, 2143–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, F.; Song, B. Public-Private Partnership (PPP) project government dynamic incentive and supervision mechanism. Chin. Manag. Sci. 2010, 18, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Fan, Z.; Shi, Y. PPP model highway project optimal ownership structure research. Manag. Eng. J. 2011, 25, 154–157. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, J. Influence of government credit risk on ppp projects in operation stage. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2021, 25, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hou, W.; Qian, Y. A dynamic simulation model for financing strategy management of infrastructure PPP projects. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2020, 24, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P. Project Selection of Government Guarantee in BOT/PPP Project Finance. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2020, 10, 1107–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martimort, D.; Pouyet, J. To build or not to build: Normative and positive theories of public–private partnerships. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2008, 26, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jia, K.; Sun, J. The concept, origin, characteristics and functions of public-private partnership (PPP). Financ. Res. 2009, 10, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Moszoro, M. Efficient public-private capital structures. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2014, 85, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaee, A.M.; Sardroud, J.M. Public-private-partnerships (PPP) enabled smart city funding and financing. In Smart Cities Policies and Financing; Vacca, J.R., Vier, E.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, N. Economic game between central and local governments during economic transition. Manag. World 2001, 3, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Gu, Q. Financial centralization and local government behavior change-from the hand of aid to grab the hand. Economics 2002, 2, 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y. Tripartite Evolutionary Game Analysis of Local Government Debt Risk Control—Based on the Perspective of Fiscal Decentralization. Tech. Econ. Manag. Res. 2021, 294, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, C.; Ke, X. Since the reform and opening up, China’s local government debt financing evolution. Local Financ. Res. 2019, 4, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Dong, Y. Improvement of local financial supervision system based on central-local game. Macroecon. Res. 2021, 268, 25–38,84. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, W.; Liu, K. Stimulation plan, state-owned enterprise channels and land transfer. Econ. Q. 2016, 15, 1225–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, J. A simple rational expectations Keynes-type model. Q. J. Econ. 1983, 98, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, K. Risk Stress Test of Local Financing Platforms under Asset Jump Situation. Financ. Res. 2013, 2, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, G.; Hao, S.; Li, X. Project Sustainability and Public-Private Partnership: The Role of Government Relation Orientation and Project Governance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Zhang, B.; Tiong, R.L.K. Official Tenure, Fiscal Capacity, and PPP Withdrawal of Local Governments: Evidence from China’s PPP Project Platform. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Game Subjects | Payment Matrix | Reasons | Governance | Methods | Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang Junqiang, Zuo Ting [15] | Central Government Local Government | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Li Jingwei, Tang Xin [16] | Central Government Local Government | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Zhou Lili, Cao Honghui [17] | Central Government Local Governments | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Liu Hao, Chen Gong [18] | Central Government Local Government | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Peng Wangxian, Ye Shujun [19] | Local governments financial institutions | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Ma Jinhua, Yang Juan [20] | Central Government Local Government Financial Institutions | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Han Wenyan, Gao Cheng [21] | Central Government Local Government | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Su Ying and Liu Xing [22] | Central Government Local Government | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Tao Yuanlei [68] | Central Government Local Government Financial Institutions | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Zhao Bin, Wang Chaocai, Ke Xie [69] | Central Government Local Government | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Hu Jiye, Dong Yawei [70] | Central Government Local Government | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Proposed Study | Central Government Local Government | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Local Government | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Financing Platform | PPP | ||

| Central Government | Financing Platform | ||

| PPP | |||

| Land Price Premium | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 2 | Local government | PPP | Financing platform | Financing platform | Financing platform |

| Hypothesis 3 | Central government | PPP | PPP | Financing platform | PPP |

| Hypothesis 4 | Local government | PPP | Financing platform | Financing platform | Financing platform |

| Central government | PPP | PPP | Financing platform | PPP |

| Component | Environment |

|---|---|

| Operating system | Windows 7 |

| CPU | Intel Core i3-3217U CPU @1.80GHz 1.80GHz |

| Memory | 4.0 GB |

| MATLAB | version R2012a (7.14.0.739) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, F.; Hang, L. A Game-Theory-Based Interaction Mechanism between Central and Local Governments on Financing Model Selection in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169821

Xie F, Hang L. A Game-Theory-Based Interaction Mechanism between Central and Local Governments on Financing Model Selection in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):9821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169821

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Fusheng, and Lei Hang. 2022. "A Game-Theory-Based Interaction Mechanism between Central and Local Governments on Financing Model Selection in China" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 9821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169821

APA StyleXie, F., & Hang, L. (2022). A Game-Theory-Based Interaction Mechanism between Central and Local Governments on Financing Model Selection in China. Sustainability, 14(16), 9821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14169821