1. Introduction

Education is affected by rapid societal changes, specifically globalization and economic nationalism, poverty and inequality, and digital technologies [

1,

2]. Furthermore, because of high unemployment, poverty, massive inequalities, and high corruption, special education teachers in developing countries are confronted with a shortage of teaching and learning resources, a lack of professional development opportunities, large class numbers, inadequate knowledge of disabilities, and insufficient access to assistive learning devices, which are critical for learners with disabilities [

3]. Additionally, teachers complain about poor work conditions and salaries and lack of job and organizational resources [

4]. The latter context is highly applicable to Namibian special education teachers. Namibia has 1184 schools, with an estimated student population of 755,943, of which 24,005 are learners with disabilities enrolled at 17 special schools, special classes within mainstream schools, and inclusive schools around the nation (

http://www.moe.gov.na (accessed on 11 July 2022)). In addition, an estimated 300 special education teachers are employed at these schools, significantly fewer than mainstream education teachers. With an increasing number of special-needs learners, Namibia faces a teacher shortage. More than 300 learners with special needs are waiting for enrolment at special schools in Namibia, which means that many learners with disabilities do not have access to education.

Special education teachers have acquired tertiary education training and specialized in inclusive education. They are trained to educate learners who have disabilities, ranging from visual impairment to intellectual impairment. More specifically, teachers are trained to deal with and manage the physical, emotional, and psychological demands of each disability. However, a lack of teacher expertise in special education, increasing class sizes, a lack of teaching resources, and a lack of safe accommodations for learners with disabilities are some of the challenges reported as hindering quality education provision in Namibia. Special education teachers must accommodate diverse learning needs, which adds to their heavy workload. Furthermore, while all teachers in Namibia face poor work conditions, a lack of resources, poor remuneration, and career advancement opportunities, special education teachers face more challenging demands and fewer resources, resulting in precarious employment. Therefore, precarious work can put the sustainable employability of special education teachers in Namibia at risk.

Employment insecurity and inequalities across the labor market have grown [

5], leading to concerns about precarity and precariousness and the sustainable employability of special education teachers. According to Baart [

6], precarity refers to more than poverty, unemployment, and poor conditions of employment. Pervasive uncertainty that affects people’s emotional, psychological, and social well-being is the hallmark of precarity. People’s lives are precarious because they are dependent on and vulnerable to others [

6]. Traditional notions of precarious work include unstable work experiences that are poorly protected, insecure, economically and socially vulnerable, and at-risk [

7,

8,

9]. The effects of precariousness extend beyond the workplace: it affects individual health and well-being, family functioning, community integration, and social cohesion [

10,

11,

12]. Moreover, anxiety, anger, anomie, and alienation caused by precarious work can lead to workers adopting strategies (such as disengagement and withdrawal) to protect themselves from precarious work environments [

7]. The challenge for educational institutions is to build and retain a teacher workforce with capabilities to meet quality education demands. However, no studies have been found on the employment precariousness of teachers in sub-Saharan Africa. Dimensions of precariousness can manifest in distinct forms, depending on a country’s work context and economic structure [

9]. For example, special education teachers face low-quality work environments characterized by inadequate financial and non-financial rewards, poor working conditions, and a lack of supporting structures [

4,

13,

14]. Notably, a cross-sectional study in the United Kingdom found that transitioning to low-quality work (as described above) caused more chronic stress and poorer health outcomes than being unemployed [

12].

Special education teachers should have the capabilities to function well in their work environment. The capability approach (CA) [

15], and specifically the sustainable employability model [

16], provides a framework for investigating the capabilities and functioning of people. Van der Klink et al. define sustainable employability as follows: “… throughout their working lives, workers can realize tangible opportunities in the form of a set of capabilities. They also enjoy the necessary conditions that allow them to make a valuable contribution through their work, now and in the future, while safeguarding their health and welfare. This requires on the one hand a work context that facilitates them, and on the other hand, the attitude and motivation to exploit these opportunities” [

16] (p. 4). The sustainable employability model focuses on what employees value and whether they are enabled and capable of achieving what they value [

17,

18]. Capabilities and functioning (as conceptualized in the CA) are two critical concepts in the sustainable employability model. Capabilities are individuals’ freedom to do and be what they value in their work or lives, whereas functioning represents individual beings and actions [

18].

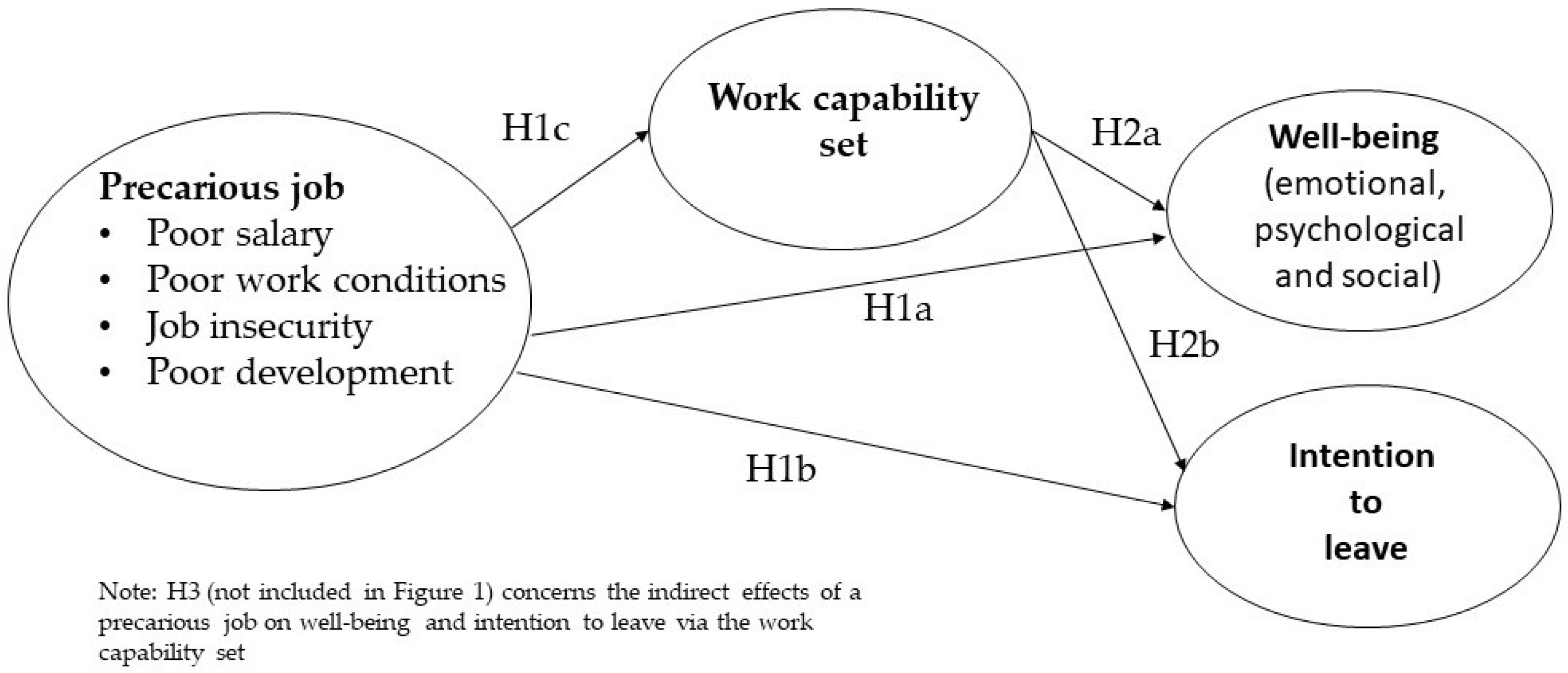

Precarious employment may impact special education teachers’ capabilities [

16] and affect their functioning (e.g., flourishing and intention to leave). Individuals who experience precarious employment and lack capabilities will languish rather than flourish and may consider leaving their jobs [

19,

20]. Well-being and retention of special education teachers can be achieved if teachers lead the lives they want and have reason to value [

15]. More importantly, teachers must be enabled to live such lives [

17]. Precarious employment and its effects on employees’ capabilities and functioning are largely unexplored in sub-Saharan Africa (except for job insecurity as a dimension of precarious employment). Therefore, this study focused on the associations between precarious employment, capabilities, and functioning of special education teachers in Namibia from the perspective of the sustainable employability model.

1.1. Precarious Employment

Two complementary perspectives, precarity and precarious employment, that questioned the notion of stable, secure employment emerged separately [

7]. The precarity concept, central to sociological thinkers’ conceptions of modernity, developed first. In addition, studies regarding precarious work have shaped the thinking of researchers during the past few decades. Campbell and Price distinguish precarity from precarious employment and precarious work [

21]. The term “precarity” refers to social conditions and accompanying insecurity that precarious workers experience, which extends to other aspects of their lives. Precarious employment describes experiences of a poor-quality job or work situation characterized by uncertainty, such as low wages, job insecurity, and limited control over pay and conditions of employment [

5]. Precarious work refers to waged work that exhibits several precariousness dimensions.

A precarious job is any job that does not have employment entitlements and protections that are found in standard employment (e.g., a well-paid job, manageable workloads, and sufficient job resources). Importantly, precariousness should include all types of employment, not just non-standard types (e.g., casual employment and temporary or contract work) [

22]. In addition to precarious employment in certain non-standard forms, its emergence occurs in standard or permanent jobs due to labor restructuring and labor market deregulation. Thus, the research potential of precariousness lies in the fact that it can be used to analyze the quality of various occupations [

22]. Job insecurity, income insufficiency, and lack of protection and rights are three dimensions of precarious employment that affect employees across various industries [

5,

23].

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), precarious work includes distinct characteristics such as unpredictable employment durations, disguised or ambiguous employment relationships, the absence of traditional employment benefits, and insufficient wages [

9]. Moreover, union membership and collective bargaining are difficult because of significant legal and practical barriers (e.g., lack of financial resources, politicization, and poor leadership). Even though more countries formally guarantee core labor rights, precarious work makes it harder for workers to exercise them. As a result of the erosion of the employment relationship, workers cannot exercise their rights, which is a reason why collective bargaining is challenging to expand.

Precarious employment has three dimensions: people losing their jobs, fear of losing their jobs, and not having alternative employment opportunities in the labor market [

24,

25]. In this regard, precarious employment is linked to sustainable employability [

16]. Kreshpaj et al. identified three dimensions of precarious employment: job insecurity, inadequate income, and work conditions (e.g., a lack of rights and protections) [

5]. Finding and maintaining paid work is essential to many individuals, enhancing their quality of life [

26]. However, precarious work conditions, such as job insecurity and low salary, can cause work to become a burden [

24,

27]. Precarious employment is also applicable to the work of special education teachers. Heavy workloads, poor remuneration, a lack of recognition, large classroom numbers, a shortage of adequate teaching and learning resources, limited time to properly engage with work, and inadequate support seem to negatively affect special education teachers’ capabilities and functioning (for example, their flourishing and intention to leave) [

28,

29]. For special education teachers to feel and function well in their jobs, they should value their work, feel enabled to perform the tasks, and feel skilled to achieve what they value.

The ILO argues that precarious work has become a global phenomenon affecting the health and well-being of workers, their families, and the societies in which they live [

9]. Having precarious work increases the likelihood of having a precarious life characterized by uncertainty, impairing one’s ability to freely plan and participate in the economy and society [

24,

30]. Therefore, uncertainty in the workplace affects employees’ capability to be and do things they consider valuable. Consequently, the ability to feel and function well is affected when teachers are not capable.

The quality of a job is an indicator of precarious employment [

22,

31]. Assessing a job’s quality involves considering the conditions associated with precariousness and the objective and subjective conditions of that job. Furthermore, research on job quality has advanced beyond objective work conditions to studying precariousness in terms of subjective aspects of employment, such as job satisfaction, relationships with peers, and the control and intensity of the job [

32]. Job quality is a set of features that provide job holders with job-related variables they need from work, for example, “pay, skill, effort, autonomy and security” [

33]. Well-being is affected by these factors. Moreover, a meaningful job, an adequate salary, and a sense of fairness can reduce financial anxiety and contribute to feelings of self-worth. In this regard, research in England showed that teaching jobs were not highly attractive [

34].

It seems evident that pay, benefits, working conditions, and job security should be considered when evaluating a job’s quality. People with quality jobs are usually well-paid and have access to various benefits (e.g., holidays, sick leave, career’s leave), safe and comfortable working conditions, opportunities for development, and a steady job [

35]. In contrast, poor jobs are characterized by low pay, few non-wage benefits, poor working conditions, long hours, temporary contracts, limited job advancement opportunities, and a lack of collective voice.

1.2. The Capability Approach

According to Sen [

15] and Dalziel et al. [

36], the CA prioritizes achievements and freedoms based on individuals’ actual ability to do and be things they value doing or being. The CA can be applied to assess individual well-being and freedom, evaluate social arrangements and institutions, and design policies [

37]. The core theme of the capability approach is its focus on what people can effectively do and be, that is, on their capabilities [

15,

18,

38,

39]. Therefore, individual development and well-being are best viewed through the lens of individuals’ capabilities to function, i.e., their access to the actions and activities in which they want to engage, which Sen refers to as achieved functioning [

40]. Consequently, functioning and capabilities are the core concepts in the capability approach [

35,

36]. Capabilities describe what people can do and be, and the corresponding accomplishments exemplify functioning. Thus, in the CA framework, capabilities can best be considered as the freedoms or opportunities a person must achieve to function [

40].

4. Results

4.1. Testing the Measurement Model

Using confirmatory factor analysis, a one-factor measurement model and a four-factor measurement model of precarious employment were tested. In addition, one-factor, three-factor, and four-factor measurement models of flourishing and intention to leave were tested.

Survey items were the indicators of latent variables, and the precarious employment model consisted of the following latent variables: (1) salary, with two items; (2) working conditions, with five items; (3) job insecurity, with six items; and (4) professional development, with three items. Models of flourishing and intention to leave consisted of the following latent variables: (a) emotional well-being (three items); (b) psychological well-being (eight items); (c) social well-being (five items), and (d) intention to leave (three items). The fit statistics of the various measurement models are reported in

Table 2.

Concerning the model of precarious employment, two models were tested, namely a one-factor model and a four-factor model.

Table 2 shows that the four-factor model fitted the data better than the one-factor model. The following fit statistics were obtained for this measurement model: χ

2 = 193.33 (

df = 97,

p < 0.0000);

RMSEA = 0.07 [0.056, 0.085],

p < 0.0012;

CFI = 0.94;

TLI = 0.92;

SRMR = 0.07. All the fit indices were acceptable. Items 15 and 16 in the precarious employment four-factor model showed a high modification index (MI = 21.93), indicating that the item content overlapped. Item 15 (“I think I will not be relevant to my work in the near future”) and Item 16 (“I think I will not be able to find another job in the near future”) did, indeed, show conceptual overload. As such, the error was correlated, and an adapted four-factor model of precarious employment was fitted to the data. This model fitted the data well. The size of the factor loadings of the items on their target factors was acceptable (Salary: λ = 0.84 to 0.86; mean = 0.85; Work conditions: λ = 57 to 0.84; mean = 0.73; Job insecurity: λ = 0.45 to 0.74; mean = 0.73; Professional development: λ = 0.54 to 80; mean = 0.66). Factors were well-defined and corresponded to prior expectations.

Two-, three-, and four-factor models were tested regarding flourishing and intention to leave. The four-factor model showed a better fit to the data than the two-and three-factor models. The following fit statistics were obtained for this measurement model: χ2 = 520.88 (df = 146, p < 0.0000); RMSEA = 0.113 [0.103, 0.124], p < 0.0000; CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.92; SRMR = 0.07. All the fit indices showed acceptable fit compared to the cut-off values. Modification indices were used to increase model fit for the four-factor model. The adapted four-factor model (b) excluded Items 7 and 10 to improve fit. The size of the factor loadings of the items on their target factors was acceptable (emotional well-being: λ = 0.77 to 0.87; mean = 0.82; psychological well-being: λ = 0.69 to 0.83; mean = 0.77; social well-being: λ = 0.76 to 0.93; mean = 0.85; ITL: λ = 0.73 to 0.94; mean = 0.86). Factors were well-defined and corresponded to prior expectations.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics, Reliabilities, and Correlations

The means, standard deviations, omega reliabilities, and Pearson correlations of the variables in the current study are reported in

Table 3. All scales in the study obtained reliability coefficients above 0.70, indicating acceptable reliability [

64]. As shown in

Table 3, the capability set was positively related to salary (

p < 0.01, small effect) and professional development (

p < 0.01, medium effect) and negatively related to work conditions (

p < 0.01, medium effect) and job insecurity (

p < 0.01, small effect). The capability set was positively related to emotional, psychological, and social well-being (

p < 0.01, all medium effects) and negatively related to intention to leave (

p < 0.01, medium effect). Work conditions and job insecurity were negatively related to emotional well-being (

p < 0.01, both medium effects). Work conditions were negatively related to psychological well-being (

p < 0.01, medium effect) and social well-being (

p < 0.01, large effect). Job insecurity was statistically significantly and negatively related to psychological and social well-being (both large effects). Salary was statistically significantly related to emotional and social well-being (small effects). Professional development was positively related to emotional, psychological, and social well-being (

p < 0.01, all medium effects). Finally, intention to leave was negatively related to salary and professional development (

p < 0.01, both small effects) and positively related to work conditions and job insecurity (

p < 0.01, both medium effects).

Not shown in

Table 3 are the point-biserial correlations between the specific work capabilities and the capability set, precariousness, and functioning. The correlation coefficients between the capabilities and the capability set were all statistically significant and had large effect sizes, varying from 0.52 (earning a good income) to 0.71 (creating something valuable). Lower precariousness about salary was statistically significantly associated with developing new knowledge and skills (

r = 0.14), having or building meaningful relationships with others (

r = 0.17), earning a good income (

r = 0.37), and creating something valuable (

r = 0.16). Precariousness about work conditions was statistically significantly related to using knowledge and skills (

r = −0.21), developing new knowledge and skills (

r = −0.26), involvement in decision-making (

r = −0.37), having or building meaningful relationships with others (

r = −0.35), setting one’s own goals (

r = −0.30), and creating something valuable (r = -.25). Job insecurity was statistically significantly related to involvement in decision-making (

r = −0.15), having or building meaningful relationships (

r = −0.28), setting own goals (

r = −0.26), and earning a good income (

r = −0.15). Low precariousness about professional development was statistically significantly related to developing new knowledge and skills (

r = 0.21), involvement in decision-making (

r = 0.21), having or building meaningful relationships with others (

r = 0.19), setting one’s own goals (

r = 0.19), earning a good income (

r = 0.22), and creating something valuable (

r = 0.23).

The specific capabilities were also statistically significantly associated with emotional well-being (varying from r = 0.21 for earning a good income to r = 41 for having or building meaningful relationships with others), psychological well-being (varying from r = 0.19 for earning a good income to r = 35 for having or building meaningful relationships with others), and social well-being (varying from r = 0.21 for earning a good income to r = 40 for having or building meaningful relationships with others). Furthermore, the specific capabilities were statistically significantly related to intention to leave (varying from r = −0.16 for creating something valuable to r = −0.27 for using knowledge and skills).

4.3. Multiple Regression Analyses

Multiple regression analyses were carried out with precarious employment factors (as measured by the PPP), capabilities (as measured by the CWQ), flourishing (as measured by the FAWS-SF), and intention to leave (as measured by the TIS). The results are reported in

Table 4.

The results in

Table 4 are discussed for the four dependent variables (emotional, psychological, and social well-being and intention to leave) for Model 1 (including only the precarious employment factors as predictors) and Model 2 (including precarious employment and the capability set as predictors). Concerning emotional well-being as a dependent variable,

Table 4 shows that Model 1 (

F = 16.20,

p = 0.000,

R2 = 0.25) and Model 2 (

F = 18.84,

p = 0.000,

R2 = 0.33) were statistically significant. In Model 1, work conditions (β = −0.23,

p = 0.014) and job insecurity (β = −0.18,

p = 0.038) were statistically significantly and negatively associated with emotional well-being. In Model 2, job insecurity was statistically significantly and negatively associated with emotional well-being (β = −0.20,

p = 0.014), while the capability set (β = 0.31,

p = 0.000) was statistically significantly and positively associated with emotional well-being. Job insecurity was the only dimension of precarious employment that was a statistically significant predictor of emotional well-being when the capability set was entered into the regression equation. Job insecurity and the capability set explained 33% of the variance in the emotional well-being of special education teachers.

Regarding psychological well-being as a dependent variable,

Table 4 shows that Model 1 (

F = 16.51,

p = 0.000,

R2 = 0.28) and Model 2 (

F = 17.91,

p = 0.000,

R2 = 0.34) were statistically significant. In Model 1, work conditions (β = −0.21,

p = 0.003) and job insecurity (β = −0.22,

p = 0.006) were statistically significantly and negatively associated with psychological well-being, while professional development was statistically significantly and positively associated with psychological well-being (β = 0.23,

p = 0.001). In Model 2, job insecurity was statistically significantly and negatively associated with psychological well-being (β = −0.22,

p = 0.002), while professional development (β = 0.23,

p = 0.001) and the capability set (β = 0.31,

p = 0.000) were statistically significantly and positively associated with psychological well-being. Job insecurity and precariousness about professional development were the only statistically significant predictors of psychological well-being when the capability set was entered into the regression equation. Job security, precariousness about professional development and the capability set explained 34% of the variance in the psychological well-being of special education teachers.

With respect to social well-being as a dependent variable,

Table 4 shows that Models 1 and 2 (including precarious employment and the capability set as predictors) were statistically significant: Model 1 (

F = 20.72,

p = 0.000,

R2 = 0.32) and Model 2 (

F = 21.37,

p = 0.000,

R2 = 0.38). In Model 1, work conditions (β = −0.34,

p = 0.000) and job insecurity (β = −0.15,

p = 0.006) were statistically significantly and negatively associated with social well-being, while professional development was statistically significantly and positively associated with social well-being (β = 0.23,

p = 0.001). In Model 2, work conditions (β = −0.32,

p = 0.007) and job insecurity (β = −0.16,

p = 0.019) were statistically significantly and negatively associated with social well-being, while professional development (β = 0.19,

p = 0.004) and the capability set (β = 0.29,

p = 0.000) were statistically significantly and positively associated with social well-being. Work conditions, job insecurity, and precariousness about professional development were statistically significant predictors of psychological well-being when the capability set was entered into the regression equation. Precariousness about work conditions, job security and professional development, and the capability set explained 38% of the variance in the social well-being of special education teachers.

Concerning intention to leave as a dependent variable,

Table 4 shows that Model 1 (

F = 10.41,

p = 0.000,

R2 = 0.19) and Model 2 (

F = 9.78,

p = 0.000,

R2 = 0.22) were statistically significant. In Model 1, salary was statistically significantly and negatively associated with intention to leave (β = −0.15,

p = 0.034), while work conditions were statistically significantly and positively associated with intention to leave (β = 0.31,

p = 0.000). In Model 2, precarious work conditions were statistically significantly and positively associated with intention to leave (β = 0.22,

p = 0.012), and the capability set was statistically significantly and negatively associated with intention to leave (β = −0.20,

p = 0.015). Work conditions was the only dimension of precarious employment that was a statistically significant predictor of intention to leave when the capability set was entered into the regression equation. Precariousness about work conditions and the capability set explained 22% of the variance in the intention to leave of special education teachers.

Not shown in

Table 4 are the results of a multiple regression analysis with precarious employment factors (as measured by the PPP), and the capability set (as measured by the CWQ). The regression model was statistically significant (

F = 12.64,

p < 0.001,

R2 = 0.21). Work conditions (β = −0.16,

p = 0.015) and poor salary (β = −0.41,

p < 0.001) were statistically significantly and negatively associated with the capability set.

Based on the above findings, hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1c are partially accepted: poor work conditions, job insecurity, and a lack of professional development impacted the three well-being dimensions, while poor salary and work conditions impacted intention to leave. Hypotheses 2a and 2b are accepted: the capability set positively impacted the three well-being dimensions and negatively impacted special education teachers’ intentions to leave.

4.4. Indirect Effects

Mplus 8.7 was used to perform a simple mediation analysis to examine the possibility that employment precariousness indirectly affected flourishing and intention to leave via the capability set (see

Table 5). In this study, indirect effects of employment precariousness were computed and assessed using the method outlined by Hayes [

65]. Bootstrapping was used to construct confidence intervals based on the indirect effect’s empirically derived sampling distribution. Based on bias-corrected estimates, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed from 10,000 bootstrap samples.

The indirect effects of salary (β = 0.04, p = 0.022 [0.01, 0.08]) and precarious work conditions (β = −0.11, p = 0.001 [−0.19, −0.06]) on emotional well-being through the capability set were found to be significant. In addition, the indirect effects of salary (β = 0.05, p = 0.016 [0.01, 0.09]) and precarious work conditions (β = −0.12, p = 0.001 [−0.30, −0.07]) on psychological well-being through the capability set were found to be significant. Finally, the indirect effects of salary (β = 0.04, p = 0.020 [0.01, 0.08]) and precarious work conditions (β = −0.11, p = 0.001 [−0.19, −0.05]) on social well-being through the capability set were found to be significant. Concerning the indirect effects of employment precariousness, hypothesis 3 is accepted for two dimensions: precariousness about salary and work conditions. Therefore, two precarious employment factors, namely salary and work conditions, mediated the relationship between the capability set (consisting of seven work capabilities) and special education teachers’ emotional, psychological, and social well-being. The capability set did not mediate between precarious employment and intention to leave.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effect of precarious employment on the work capabilities of special education teachers in Namibia and to study their flourishing and intention to leave. Four dimensions of precarious employment were identified and studied: salary, job insecurity, professional development, and precarious work conditions. Precarious employment factors, specifically precarious work conditions and job insecurity, negatively affected teacher capabilities and teacher functioning.

The results showed that the capability set was positively associated with emotional, psychological, and social well-being and negatively associated with the intention to leave. The findings of this study confirm the findings that a capability set (i.e., all seven capabilities combined) is vital for the optimal functioning of employees [

17].

5.1. Precarious Jobs and Capabilities

The study uncovered that all four dimensions of precarious employment significantly affected special education teacher capabilities. As expected, low precariousness about salary was significantly associated with teachers’ capabilities to develop knowledge and skills, build and maintain meaningful relationships at work, earn a good income, and contribute to something valuable. Furthermore, precarious work conditions were negatively associated with their capabilities to use knowledge and skills, develop knowledge and skills, be involved in important decisions, have and build meaningful relationships with others, set their own goals, and contribute to creating something valuable. Finally, job insecurity was negatively associated with capabilities to be involved in important decisions, have and build meaningful relationships with others, set their own goals, and earn a good income. These findings align with the sustainable employability model, suggesting that constraints such as precarious employment might negatively impact work capabilities [

16].

Special education work is marked by poor salaries, shortages of teaching and learning materials, large class numbers due to a significant influx of learners with disabilities, limited time to engage in work fully, and heavy workloads, including administrative work [

66]. Precarious employment negatively affected most teacher capabilities. Precariousness about salary had the strongest negative effect on teachers’ capability to earn a good income, but it had also small negative effects on other capabilities, such as developing new knowledge and skills, having or building meaningful relationships with others, and creating something valuable. Precariousness about work conditions had the strongest negative associations with three capabilities, namely involvement in important decisions, having or building meaningful relationships with others, and setting one’s own goals. However, it also had small negative effects on using knowledge and skills, developing new knowledge and skills, and creating something valuable. Furthermore, job insecurity had moderate negative effects on having or building meaningful relationships with others and setting one’s own goals. It also had small negative effects on involvement in decision-making and earning a good income. Precariousness about professional development had small negative effects on developing new knowledge and skills, involvement in decision-making, having or building meaningful relationships with others, setting own goals, earning a good income, and creating something valuable. Precarious employment put the sustainable employability of special education teachers at risk, which might affect the sustainability of special education in Namibia.

5.2. Precarious Employment, Flourishing, and Intention to Leave

The four dimensions of precarious employment were negatively associated with special education teacher functioning. Precarious work conditions and job insecurity were associated with poor emotional, psychological, and social well-being. Furthermore, precariousness concerning professional development was associated with poor psychological and social well-being. The findings confirm that when teachers experience or perceive their work to have low precariousness in terms of work conditions and job insecurity, their emotional well-being is enhanced, and they can experience more positive emotions in the workplace and enjoy their teaching work [

19]. In addition, enhancing psychological well-being can allow teachers to connect more productively with colleagues, have meaning attached to their teaching work, be absorbed, and experience autonomy [

46]. Enhanced social well-being of teachers will strengthen their ability to connect and feel part of their organization and feel that they contribute to its development.

Precarious work conditions, job insecurity, and poor professional development also impacted teachers’ intention to leave. Thus, if more teachers are to be retained, interventions should focus on creating an enabling work environment for them and prioritizing teacher professional development needs and compensation. Teachers must perceive that they are rewarded fairly and adequately to enable them to lead the kind of life they value. Therefore, stakeholders, such as the Ministry of Education, Arts and Culture in Namibia, should assess the constraints that teachers experience.

This study confirms the importance of professional development for teachers’ well-being and retention. In terms of professional development of special and general education teachers in Namibia, the following topics were rated as important and necessary [

2]: organizing teaching materials, learning strategies, instructional methods, behavior management, discipline, collaboration with parents/guardians, assessment, teaching life skills, learning disabilities, inclusive education, diversity, and cultural contexts; deafness or being hard of hearing, blindness or a visual impairment, collaboration with peers, behavior disorders, intellectual disabilities, and physical disabilities.

5.3. Capabilities, Flourishing, and Intention to Leave

When teachers are not capable, they may not function or feel well. Inversely, according to the sustainable employability model, capable employees may want to continue working [

16,

17]. The capability set was positively associated with emotional, psychological, and social well-being, and negatively associated with intention to leave. All the capabilities impacted the well-being and intention to leave of special education teachers. Having or building meaningful relationships with others strongly affected teachers’ emotional, psychological, and social well-being. These findings confirm the importance of work capabilities in general and specifically work relationships for the flourishing of special education teachers. Using knowledge and skills had the most substantial effect on their intention to leave. Special education teachers need specialized knowledge and skills to deal with learners with diverse needs. Therefore, teachers who do not value using such knowledge and skills, are not enabled, or cannot achieve using their knowledge and skills will consider resigning from their jobs.

Precarious employment is likely to lead to teacher experiences of a lack of mattering, i.e., they do not feel valued or feel as though they add value [

67], and inequity [

68]. Well-being is impossible without mattering and fairness. Equity theory states that perceptions of the balance between work inputs and outcomes are vital. Individuals who experience inequity may decrease their efforts, change the outcome (e.g., demand a higher salary, seek other methods to develop and grow), or leave the organization. Therefore, the effects of precarious employment on teachers’ capabilities, flourishing, and intentions to leave might be explained by their experiences of inequity and injustice.

5.4. Indirect Effects of Precarious Jobs

The results suggest that work capabilities play an essential role in the well-being and intentions to leave of special education teachers. Precariousness indicates instability and self-defense because of teachers’ unmet relatedness, self-esteem, and welfare and security needs. Therefore, teachers might be preoccupied with security instead of development opportunities [

69].

The capability set mediated the relationships between two dimensions of precarious employment, namely salary and precarious work conditions, and emotional, psychological, and social well-being at work. Therefore, dimensions of precariousness indirectly affect the well-being of special education teachers via their capability sets. These findings support the sustainable employability model. Social justice is necessary to create opportunities for special education teachers to develop capabilities, such as using knowledge and skills, developing knowledge and skills, involvement in important decisions, meaningful contacts at work, setting own goals, having a good income, and contributing to something valuable [

42]. While injustice impairs teachers’ capabilities, external conditions of justice, such as a fair salary, good working conditions, job security, and professional development, are essential to allow teachers to create capabilities [

37]. To promote the flourishing and retention of special education teachers, they must develop all the capabilities into a capability set with the seven capabilities above a threshold [

67].

5.5. Limitations

This study had various limitations. First, a cross-sectional research design was used to measure the effects of precarious employment on special education teacher capabilities and functioning. As such, the study only obtained teachers’ self-rated assessments of the constructs in the study over a relatively short period and, more so, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, a longitudinal research design is recommended to measure such effects over time.

Second, the measure of precarious employment (PPP) which was used in this study is in need of further refinement. The reliability of this measure varied from 0.61 to 0.79, depending on the subscales of the measure. Further development and validation of the measure are recommended. Third, this study did not investigate the relationship between demographic variables and precarious employment. Future studies can uncover whether demographic variables influence special education teachers’ capability and precarious employment dimensions.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study investigated the effects of employment precariousness on special education teachers’ capabilities and functioning (flourishing and intention to leave). Teachers’ work-life quality is crucial, as it is linked to their livelihood and ability to live the kind of life they desire. Namibian special education teachers have experienced precarious working conditions for the past three decades. As a result, schools are understaffed, and overburdened teachers suffer from a declining quality of work life. Consequently, teacher sustainable employability and the quality of special education could be at risk due to teacher experiences of employment precariousness.

Stakeholders in Namibian education should take cognizance of precarious employment dimensions present in these teachers’ work conditions and develop, employ, and monitor interventions that could positively enhance teacher capabilities (as a set). Interventions will differ depending on the school context (e.g., rural versus urban). For this reason, interventions must be tailored to ensure optimal functioning for all special education teachers.

To ensure sustainable employability of special education teachers, the education department should focus on the capabilities of teachers. Interventions should focus on teachers and their contexts (e.g., the school, district, educational department, and community). First, capability development could focus on teachers’ work values, and the enablement and achievement thereof. To create the conditions for capability development, educational managers should question their core assumptions about human nature and understand how their mental models affect their managerial practices [

70,

71]. Second, a contextual approach is necessary, as functioning (e.g., flourishing and intention to leave) is often treated as an individual, isolated, and personal experience unrelated to contemporary workplaces’ problematic structures and agendas. Stakeholders in the Namibian educational system should implement interventions to address precarious employment through effective and efficient recruitment and selection, induction, training and development, coaching and mentorship, occupational health and well-being, performance management, and remuneration. In the performance management process, managers and teachers must understand the seven capabilities and communicate about values, enablement, and achievement (as elements of capabilities). Although resource and support provided to improve work conditions at schools is a complex issue, special schools must be capacitated to formulate and implement school-level interventions according to these schools’ work conditions. Schools are encouraged to strategize on resource mobilization and garner support from private and non-governmental organizations who, obligated by their corporate social responsibility, could develop flourishing teachers and learners.