1. Introduction

According to the Singapore Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Singapore, which covers 275 square miles and is inhabited by five million people, a country that is smaller than the state of Rhode Island, is one of the most economically developed countries in Southeast Asia [

1,

2]. Singapore is also home to one of the world’s busiest transportation hubs, which caters to more than 5000 flights to and from more than 123 countries [

3]. Known as the Lion City, tourism has been one of the country’s key pillars in the service and economic sector [

4]. The growth in international visitors averages 4.5% to 5.0% annually, and according to UNWTO’s International Tourism Highlights 2020 Edition, Singapore’s international tourism receipts are the highest in Southeast Asia [

5,

6].

Singapore’s tourism receipts are segregated into five different components: (1) shopping, (2) accommodation, (3) food and beverages, (4) sightseeing, entertainment, and gaming, and (5) other TR components [

7]. Of the five components, shopping contributes the most to the total value added (VA) and the country’s GDP. However, despite contributing an average of 4% to the country’s GDP, tourism in Singapore witnessed a shift in spending patterns that resulted in a reduction in these contributions [

5]. In addition, although there was a growth in international visitors for more than 20 years, there was a decrease in 2008–2009 due to the financial crisis [

8]. However, the slump caused by the COVID-19 pandemic was the most significant in the last two decades.

Due to the rapid spread of the COVID-19 virus in late 2019, Singapore gradually tightened its border controls from early January 2020 until the end of 2021 [

9]. Starting in early 2020, Singapore imposed physical-distancing measures to prevent the possibility of transmission, and a quarantine order was enacted [

10]. The next significant step Singapore took was the initiation of Phase 2 of the Circuit Breaker on 19 June 2020; in this phase, the tourism sector was allowed to apply to reopen, and eventually, on 28 December 2020, the tourism sector was allowed to increase its operating capacity up to 65% [

11]. A new program, called Vaccinated Travelers’ Lane (VTL), allows people to travel to certain countries with certain procedures. Before re-opening the country to international tourists, Singapore created a campaign to reassure locals and encourage them to travel within Singapore. Subsequently, along with the border-tightening measures, the Singapore government also launched a nationwide campaign, called SG Clean, in February 2020 [

12]. In this campaign, the Singapore government used the SG Clean certification, which is the national mark of excellence for environmental public hygiene and was created to rally businesses and the public to uphold food sanitation standards and hygiene practices [

13]. The web page of SG Passion Made Possible was used as part of a rebranding campaign aiming to drive visitors to visit Singapore while upholding personal hygiene within the SG Clean standards [

14].

The research regarding SG Clean is still limited. However, a previous study mentioning SG Clean was focused on dengue prevention. The major focus of the dengue campaign was on promoting public cleanliness, such as maintaining clean premises and preventing littering, which eliminates mosquito breeding habitats and reduces the spread of dengue in addition to COVID-19 [

15]. Prior research focusing on the Marina Bay area in Singapore, a key site of post-independence Singaporean urbanism, examined the Marina Bay area to determine how dimensional urban development has been combined with governance practices to produce and extract new territory, showing that the Marina Bay area has become one of Singapore’s most important areas [

16]. Staying in this integrated resort is considered a positive and memorable activity [

17]. A number of studies have used text mining techniques, such as content analysis, frequency analysis, text-link analysis, and latent semantic analysis, to analyze customer satisfaction with hotel products and services [

18]. A previous study also discussed customer perceptions, including satisfaction and dissatisfaction, based on the premise that positive reviews indicate satisfaction and negative reviews indicate dissatisfaction [

19]. A more recent study described how the linguistic style in textual reviews affects customer satisfaction [

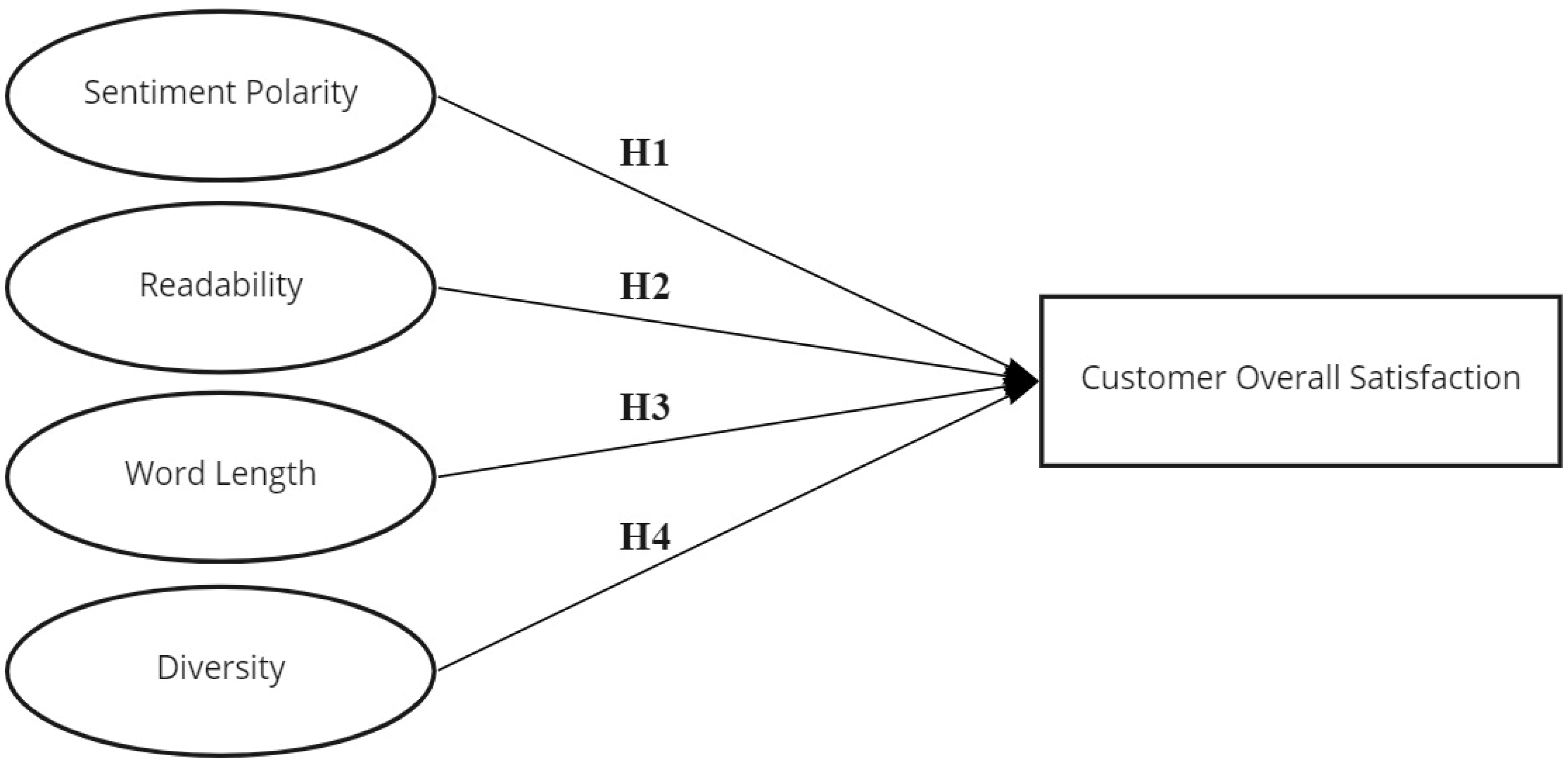

18]. The attributes utilized in this study were sentiment polarity, subjectivity, readability, diversity and word length [

20].

Singapore is stepping into a transition towards a new normal; consequently, the tourism and hotel industry needs to be prepared. Based on a review of previous studies, there is limited research utilizing the linguistic styles of customer textual reviews in Singapore SG-Clean-certified hotels. Thus, the main objective of this research is to determine the key attributes affecting customer satisfaction post-COVID-19 in luxury hotels in Singapore’s Marina Bay area by using text mining. In order to achieve these objectives, this study adopted text mining analysis to uncover customer experiences based on online reviews and regression analysis to uncover the main attributes affecting customer satisfaction.

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Discussion

Our results supported H1: overall customer satisfaction is affected by sentiment polarity. Sentiment polarity refers to the sentiment score inside a customer textual review, and it was proven to have the most effect on the customers’ overall satisfaction. It indicates higher sentiment polarity in the customer textual reviews of the luxury hotels in Singapore’s Marina Bay Area, which suggests that more positive words were used in their online reviews than negative words [

51]. Positive emotions, including excitement and delight, are expressed by customers with higher sentiment polarity in their online reviews, which is correlated with higher ratings [

18,

51]. The reviews with high sentiment scores, which positively affected the overall customer satisfaction, featured comments such as: “Friendly staff and the room is impressive. Great view of the Suntec fountain and marina bay area. Room is spacious and full of facilities. The charging port is convenient for international travelers. I loved this place”, with a sentiment score of 0.72; “Wonderful experience great place to stay nice view of bay. Located in central financial region of SG clean and neat near to airport. Easily accessible to all regions”, with a sentiment score of 0.68; and “We had a short staycation and it was a delightful experience! They served decent ala carte buffet breakfast with indoor & outdoor dining area. There are time slots to choose for breakfast and use of swimming pool and gym to avoid overcrowding. Staff are friendly and attentive. Will definitely go back again!”, with a sentiment score of 0.79. We identified many positive adjectives included in the reviews above, such as “wonderful”, “delightful”, and “friendly”.

The second hypothesis in this study was H2: overall customer satisfaction is affected by readability level. However, compared to the other independent variables, readability showed the least effect on overall customer satisfaction. These results suggest that, for primarily satisfied customers in Singapore’s Marina Bay area, a higher readability of online reviews led to a higher level of satisfaction during their stay at in the Marina Bay area. The length and readability of a review text is a two-dimensional quantitative indicator of its understandability, which signifies the extent to which the information content can be absorbed by users, which can reflect their satisfaction [

70]. Satisfied customers write clearly in their reviews, as indicated by their choice of sophisticated and professional language. Perceiving a higher degree of professionalism in online reviews influences customers to perceive higher quality in their own stay, thereby increasing their satisfaction [

71]. The reviews with high readability scores positively affected overall customer satisfaction, including reviews such as: “Nice and relaxing staycation. Breakfast and dinner were fantastic. Staff make us feel comfortable when taking our order”, with an ARI score of 7.70; “One of the best hotels that I have stayed at from the service to the attention to detail and the view of the bay”, with an ARI score of 8.00; and “A wonderful place to relax with a drink and the view across the water straight to Marina Bay”, with an ARI score of 7.20.

H3: overall customer satisfaction is affected by word length, was also supported by the results. A possible explanation for this is that satisfied customers are motivated to write well-written and in-depth reviews, while unhappy customers tend to use reviews to vent their frustrations and provide less useful information [

72]. In this study, it was concluded that the length of a customer’s online review has an impact on the value of their satisfaction. The reviews with high word-length scores positively affected overall customer satisfaction. Most websites monitor review quality by monitoring the review length. Amazon has a minimum word count of 20 words and no maximum. TripAdvisor requests users to describe their travel experiences in at least 200 characters [

70]. Among the diverse features of the review text, length and readability are two of the most influential textual features that can affect the quality of reviews, since the review length directly determines the amount of information that a review contains.

The fact that the review length and readability were more influential is evident from their significant and relatively large coefficients in the parameter estimates compared with the other factors. For example: “I had a fantastic time at the hotel. Checking in was swift and professional. The lovely lady who served us was very friendly attentive and helpful when it came to rectifying issues with my reservation and she went that extra mile to make my birthday stay even better. Our first stop was the Lobby Lounge for afternoon tea. Our host who we didn’t get his name seated us and introduced the menu. He went through each item in detail and explained them to us. And also, thanks for the birthday cake surprise! It was very much appreciated. The room was gorgeous and even had treats for us. There’s a cute bear on the bed lots of spaces for our stuff and a rubber ducky in the bathtub. I found the customer service in the executive lounge to be superb. The host introduced us to the executive floor and was very warm and welcoming. However, the breakfast buffet was over-crowded and there wasn’t much variety in their food offerings. Though I will say their waffles and ice cream combination was pretty decent. The friendly staff and great service at this hotel are unmatched. I highly recommend it!”. This review features 234 words.

By contrast, the unsatisfied customers preferred to write short reviews, such as: “Would never stay here again. Bad service. Doesn’t participate in bonvoy and the rooms are super dated. The worst Marriott hotel in Singapore”, with a total word count of 23, and “Terrible. From the moment of check in the experience was horrible. Staff tried to convince us of an upgrade for $30. Only to find out after checking out that my booking for was an upgraded ocean view. Breakfast was to be included but was asked to pay during checkout”, with a total word count of 49.

Lastly, H4: diversity has a positive impact on the overall customer experience in luxury hotels, was found to be incorrect. Diversity in fact had a negative effect on overall customer satisfaction. The number of varied words or unique words used by past customers was proven to not have any effect on overall customer satisfaction. Low diversity also indicated that customers used the same words to convey their disappointment [

20]. The reviews with high diversity scores did not necessarily affect overall customer satisfaction, as shown by reviews such as: “Umm... this beautiful hotel has served very horrible food unlikely other 5 star hotels. amazingly bad. I tried 3 different types of breakfast menus. But all are so so or bad. When I asked my friends some nice food in the hotels many of them said the hotel provides good view but not good food. It’s TRUE. I think it’s Far East organization issue. When I went to oasia hotel in Tanjong Pagar i felt same thing. It’s same company... OMG. Next time if you come here don’t include breakfast or try any meals here. But I still love this hotel location and view. That’s why I gave 3 stars otherwise I may give 2 stars.”, with a total unique word count of 81, which, if divided by the total number of words, 112, produces a diversity score of 0.72. In this review, the customer repeated the terms “bad”, “breakfast”, and “same” to convey their negative experience.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

Many hospitality studies using big data focus on finding key attributes that affect customer satisfaction. However, studies applying big data to luxury hotels in Singapore are lacking. In order to gain a better understanding of consumer behavior in, for example, the e-commerce environment, which is dynamic and rapidly evolving, researchers have used online reviews to model and test the influences of reviews, reviewers, products, and consumer characteristics on consumer outcomes [

73]. Compared with other studies, this study focuses more on processing the customer textual reviews in luxury hotels in Singapore’s Marina Bay area using different variables and determines the overall customer satisfaction according to these variables. These variables represent the linguistic styles of online reviews, which reflect the writing style of each customer. This study offers three theoretical implications and contributions.

First, this study shows the relationship between two independent variables, linguistic style and overall customer satisfaction. Compared with overall customer satisfaction, customer textual reviews reflect past consumption experiences. This study focuses on using the linguistic styles in which customer textual reviews were written to predict customers’ overall satisfaction in luxury hotels in Singapore’s Marina Bay area. This supports the results of earlier studies by determining how the linguistic style of an online review provides feedback on a hotel’s overall customer experience to future customers and hoteliers.

Second, this study’s findings provide further support for earlier studies regarding the linguistic style of online reviews. Previous studies mentioned that sentiment polarity significantly influences customer satisfaction [

18]. This was also shown in the results of this study.

Finally, this study supports earlier studies in the manner in which the patterns of the linguistic styles generated by past customers were examined. This study utilized a sample of 8441 online reviews of seven luxury hotels in Singapore’s Marina Bay area to analyze the business value of customer textual reviews in the hospitality industry. By mining the linguistic styles of customer textual reviews, we were able to handle the vast amount of information.

6.3. Managerial Implications

Through social media and online platforms, consumers express their thoughts and feelings through online reviews of many products and services more freely and openly than before. Businesses may benefit from this abundance of information by adjusting their strategies to gain a competitive edge. Enhancing customer satisfaction is a key to remaining competitive in fiercely competitive markets succeeding in the social media space [

47].

Overall customer satisfaction is an important part of the hospitality industry. Previous studies showed that customer satisfaction leads to loyalty [

74], and other studies mentioned that satisfaction leads to repurchase intentions [

75]. Consequently, overall customer satisfaction has many implications for management. The first finding of this study allows the industry to recognize the attributes affecting overall customer satisfaction through the frequency analysis. Consequently, the luxury hotel management will be able to focus on specific attributes to improve customer satisfaction, allowing management to reach financial goals and other targets.

As a result of this study, luxury hoteliers may be inspired to explore more attributes of customer textual reviews and to investigate the behaviors of online reviews and their relationship to overall customer ratings. Online reviews contribute greatly to the eWOM effect, which has the potential to influence future customer booking decisions in luxury hotels [

18]. As a result of this research, industry managers can understand how the styles of textual customer reviews relate to overall customer satisfaction, based on data-mining methodologies. It is important for luxury hotel managers to be aware of and improve the products and services on which their customers provide feedback, but it is also vital to emphasize the linguistic styles of customer reviews. Ultimately, the results of this research will allow the luxury hotel managers in the Marina Bay area in Singapore to determine the key attributes affecting customer satisfaction and interpret customers’ experiences based on their reviews in a post-COVID-19 context.

7. Conclusions and Limitations

7.1. Conclusions

Consumer opinions can either enhance or jeopardize a hotel’s reputation. Negative comments have the potential to tarnish the projected image of a hotel and persuade potential customers to seek competing products/services [

44]. Consumers increasingly use the internet to share experiences, especially regarding services provided by all kinds of companies. The opinions of consumers posted online express reliability and can influence the decisions of other consumers when they purchase products or services [

44].

With a sample of 8441 online reviews, this study predicted overall customer satisfaction through the attributes of customers’ textual reviews. The words “hotel”, “room”, and “service” were the three most frequently used words. Among all of the independent variables examined, this study showed that sentiment polarity has the greatest effect on overall customer satisfaction. In addition to readability and word length, other variables also contributed to customer satisfaction, albeit in a limited way. The last variable, diversity, showed no significant impact on customer satisfaction.

7.2. Limitation and Future Research Directions

Throughout the research, we found that there were some limitations. As SCTM 3.0 is still in development, only customer ratings, review texts, the duration of data, writer ID, and hotel names could be crawled. Future research may be more heuristic if other variables, such as service quality, can be crawled as control variables.

On the other hand, the data utilized for this study were collected from early 2020, covering a total of 2 years. Future research would benefit from the use of a longer period of time to gain more information. Second, this study is based on customer textual reviews written in or translated into English; however, linguistic styles could differ between languages and culture [

18]. Therefore, future research could conduct a similar approach, but compare across languages and cultures. Third, this study did not classify the reviewers according to different levels, which led to varied data. In future research, the reviewer level should be considered to obtain more specific results.

The application of a similar approach to other parts of the hospitality industry, such as airlines, ship lines, restaurants, and MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conventions, and Exhibitions), would also be of interest. In the hotel industry itself, a specific study on the relationship between the linguistic styles of customer textual reviews and particular products or services would be of additional interest to hotel management.