Abstract

The effects of shrinkage can be manifold. Vacant green areas are a typical manifestation of shrinkage in deindustrialized cities, such as Heerlen, Netherlands. Such challenges are usually managed by the municipality which, due to financial reasons, often has to turn to citizens to aid in accommodating those effects. The example of Gebrookerbos in Heerlen shows how an adaptation of governance processes can take place in order to facilitate the involvement of citizens in reusing vacant spaces. The introduction of the position of account manager as well as brooker are being regarded as essential for shortening the distance between municipality and citizens as well as contributing to replacing the mistrust towards the municipality, which is in line with existing research on depopulating areas. Further, making a plethora of funding options and projects available for civic initiatives ensures the longevity of civic involvement. Finally, the findings show how working on the “hardware”, the visible vacancy and deterioration of the land—by adapting the “software”, the institutional set up and focusing on civic empowerment—of a shrinking city can go hand in hand.

1. Shrinking Cities: A Challenge to Governance

Shrinking cities are a ubiquitous occurrence [1] and the research thereof has proliferated largely in the last two decades. Despite the increase in scholarly research and public interest, the phenomenon is not novel as fluctuations in population loss and growth have been part of urban development processes forever. While population loss is indeed an obvious and widely used indicator for shrinkage [2] and offers a common quantitative variable for tracking shrinkage, a collective definition of shrinking cities is still missing. This is due to the many contextual circumstances which differ not only from country to country, but from one city to another. The diversity among shrinking cities has been acknowledged and highlighted by many scholars [2,3,4,5,6] and provides understanding as to why certain measures to deal with shrinkage do not work across all cities. As Oswalt [7] underlines, shrinkage is an accumulation of various transformative processes. Such changes take place in the demographic, cultural, political, economic and/or planning sphere and therefore simultaneously imply the transformation or change of social relationships. Particularly in long-term shrinking cities, where transformations are gradual processes rather than ad hoc crises, a closer look at adaptations of social relationships between actors can provide insight into how the local governance can be adjusted to meet the conditions of shrinkage.

Understanding shrinkage and the planning thereof as unpredictable, this research takes a closer look at how different stakeholders in shrinking cities interact and scrutinizes how governance processes are adapted in order to make way for increased civic involvement. The term Governance is operationalized following the definition of urban governance by UN-Habitat, and is understood as interactions and relations between (individual) public and private stakeholders in a particular local institutional setting. This setting in turn is embedded in a larger political, economic, cultural and demographic context.

In light of vacancy representing a major challenge in the case of Heerlen, Netherlands, this article deals with the question of how changes are implemented in governance processes in order to deal with the degradation and nuisance of such vacant spaces. In particular, the roles of and interactions between community on the one hand and policy actors/ the local administration on the other are scrutinized. In this regard, the project and method “Gebrookerbos” (2014–2021), deemed a huge success, are studied. The article starts by reviewing existing literature on civic engagement in shrinking cities and explores the link to the reuse of vacant spaces. Here, it addresses current debates on the role of citizens in the context of urban shrinkage. It then continues with the introduction the case study area and the project investigated. Following that, the methodology is presented before the article moves on with the description of the results. Section 6 proceeds with a discussion of the findings of this research and addresses them with regard to existing research on similar topics. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the most important findings of this study. This article forms the continuation of the discussion on the role of individuals in shrinking cities and extends the work of already published articles on Heerlen, Netherlands such as Ročak (2016 and 2019), Hoekstra (2020) and Elzerman and Bontje (2015). It contributes to the discussion on alternative planning strategies in shrinking environments and highlights the importance of relations between institutions and individual citizens. Touching upon the concept of “hardware” and “software” it takes a look at temporary use of vacant spaces and offers another perspective on community-led neighbourhood development in times of weakened public resources.

1.1. Uncertainties as Trigger for Civic Engagement?

Shrinkage triggers deep transformations and undoubtedly drives uncertainties in various areas including policy and decision-making [8]. The variety of trajectories of shrinkage shows how unpredictable future developments are, let alone allows for the prediction of stabilization or even re-growth [2,9,10]. However, as Boelens and de Roo underline [11], process-oriented actions that go beyond the traditional technocratic planning approaches have a greater ability to adapt to changing and uncertain contexts. Hierarchical and top-down governmental decision-making and policy implementation can in turn fail to effectively address problems in urban development and particularly in fragile moments, such as shrinkage. Moreso, a city’s process of adjustment to changing circumstances [12] is very much a result of processes that happen within. Such local changes can include actions by citizens or initiatives by entrepreneurs or local authorities, as well as collaborations and interactions between those stakeholders. In turn, these interventions can trigger changes at a higher administrative level, as well as increase the chances of joint agreement of decisions [13] (p. 27).

In the light of shrinkage and the challenges that can come with it, citizens and their potential involvement in urban development processes is a particularly interesting and challenging [14] one. In growing and prospering environments, the involvement of civil society in governing the urban realm is already a well-studied and acknowledged one. However, in the shrinking context, civil society has been an unexploited source [15] for a long time due to several issues. Firstly, motivating residents to get active and involved in reinventing vacant spaces in their once thriving neighbourhood is a task, especially when trust in the public sector tends to be harmed [14] and an overall pessimistic and sceptic attitude overruns the communication between actors. Further, as Hospers [3] concludes, there can be different expectations in the future of the city between public officials and residents. Similarly, the situation can be viewed differently and shrinkage itself might not be regarded as such a problem for citizens, whereas numbers and economic profits tend to matter for city governments in the first place. Lastly, the challenge of to what extent citizens are involved and responsibility is transferred has not skipped shrinking cities. Active citizenship and the big society can be manifested in shrinking environments, as some problems that come with shrinkage do not require financial capacities [3], but rely much more on investing time, knowledge and physical capacity. In fact, scholars underline that in the presence of social capital, civil society is indeed able to govern urban shrinkage [14]. Particularly, as Meijer [16] points out, the challenges of shrinkage can lead to a political and planning vacuum, which in turn can offer potential for civic involvement. However, governance structures also tend to be rather formal and follow regulated processes [17] within a very bureaucratic system [ibid.] and additionally prevent civic engagement. Therefore, scholars underline that local authorities need to actively stimulate and facilitate, and not merely talk about increasing civic involvement [18,19,20,21].

However, different actors’ interests, power relations, as well as institutional settings and the local context play key roles [22]. As highlighted by Hospers [3], there is a need for rethinking and adjusting certain responsibilities and roles in a shrinking environment. The governance challenge becomes especially evident in the form of enhanced financial challenges as a result of lower tax bases in many depopulating environments, monetary resources and therefore capacities for urban development are oftentimes lowered or result in the vanishing of crucial governmental services. Hence, several authors suggest that shrinkage requires new governance concepts to adequately address the topic [20,23,24,25]. Hospers [3] highlights that shrinkage is a “complex urban governance process” (p. 1519) in need of collaboration with different actors. Underlining that “civic engagement is Europe’s most important urban shrinkage challenge” (p. 1508), Hospers (ibid.) draws attention to the complexity of involving residents in shrinking environments. Although, theoretically and practically, the benefits of civic engagement in depopulating cities are evident and can result in fewer people leaving, the lack of empowerment, the persistence of bureaucracy and the rigidity of legal institutions still pose hindering factors. Therefore, the acceptance of shrinkage on the municipality level is a precondition to the success of increased civic engagement.

Audirac [26] emphasizes new forms of network governance that are being created in shrinking cities by local governments, entrepreneurs, artists as well as architects and planners. Vacant and abandoned spaces in shrinking cities are especially attractive for reinvention or exploration of do-it-yourself urbanism through informal urban planning. Such processes can stimulate the sustainable development of derelict spaces and the coproduction of such marginal areas by investors, municipal actors and artists or entrepreneurs.

More recent publications also critically analyse the effects of shrinkage on different social groups or the potential of their involvement in revitalization processes, such as citizens [14], the cultural sector [15] or refugees [27]. In line with this, Ročak stresses that civil society has to be involved in addressing the challenges in shrinking cities [14] in order to ensure social sustainability [28]. However, a redefinition of the ways that participation processes take place is crucial and needs to be understood in light of increasing trust between stakeholders as well as the empowerment of citizens. On the other hand, Ubels et al. [29] conclude that indeed self-governing capacity of residents in some depopulating cities is noticeable (however, can change over time due to changing governance structures). Nevertheless, within governance dynamics in shrinking cities, unpredictability and non-linearity play important roles and fluctuations in governance processes are to be expected, either intentional or unplanned [30]. Especially, as shown in the study of project Ulrum 2034, Ubels et al. [29], the role and extent of involvement of the government can change and therefore trigger changes in the overall dynamics of the particular governance arrangements. However, the self-governance capacity of citizens in shrinking environments is still very reliant on public funding and therefore rather susceptible to be steered by public stakeholders.

1.2. The Potentials of Vacancy in Shrinking Cities

The effects of shrinkage on the ‘hardware’ [20] of a city are almost inevitable. Demographic decline has effects on the visible infrastructure in cities, such as decay of surplus and vacant housing infrastructure, but also the amount of social infrastructure such as schools, hospitals, kindergartens and recreational infrastructure become increasingly obsolete. Additionally, the lower tax base due to fewer residents oftentimes results in budget cuts and therefore less capacity for the upkeep or even provision of such public services [20]. Vacant or underused green spaces due to demolition of surplus infrastructure in shrinking cities are therefore very common phenomena. Several authors have stressed the connection of vacancy or abandonment and impoverishment or safety issues [26,31] in need of action to prevent loss of quality of life in neighbourhoods [10].

Although empty spaces can offer potential for reinventing or giving new meaning to derelict areas, they have to be addressed with caution. With the emergence of the concept of temporary uses in shrinking cities, that resulted from the federal program Stadtumbau Ost in Germany, the strategy of re-using or temporary using vacant spaces has become very popular, and conflictual at the same time [10,32]. Popular, as temporary uses are able to be realized without monetary resources and in an informal way and contested on the other hand, due to their potential of being merely a stop-gap for landowners. Dubeaux and Cunningham-Sabot [10] stress how interim uses can be exploited in anticipation for profit maximization, in the case of re-growth, as can be seen in the case of Leipzig, Germany. Indeed, vacant privately owned spaces can represent a possibility, but also a major threat to neighbourhood development, dependent on the landowner’s goals.

However, in many shrinking cities, a plethora of empty spaces are owned by municipalities, due to demolition of public infrastructure. Due to budget deficits and the related loss of institutional capacity, municipalities are oftentimes hesitant, or simply not able to, apply innovative ideas or introduce experimental processes [3,21] on such empty spaces.

2. Heerlen: “The” Shrinking City

2.1. Heerlen: Deindustrialization and Its Effects

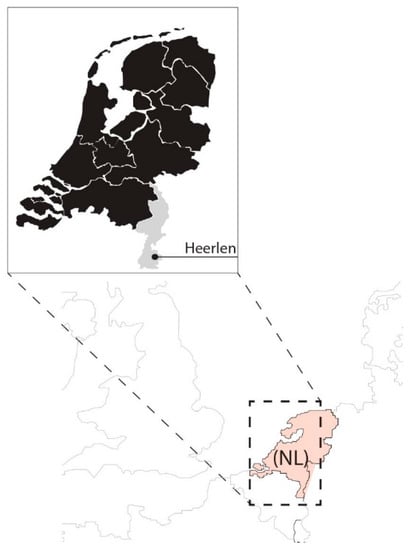

Heerlen, a city of almost 87,000 inhabitants (2020) [33], is known as the shrinking city in the Netherlands. Both the city and the Parkstad Limburg region have been subject to academic interest [14,28,34,35,36,37] as population loss and associated challenges keep persisting. The city is located in the very south of the Netherlands, close to the borders with Germany and Belgium (see Figure 1). However, strategies against this development, such as rebranding the deindustrialized area have also been implemented. Although the forecast for population development in the Netherlands points to growth, there are shrinking regions in the periphery of the country [34]. Parkstad Limburg, however, is the only urbanized shrinking area in the country as the phenomenon appears to be more present in rural areas. Once the richest city in the Netherlands, Heerlen began to lose population in the 1970s after the mining industry was closed [14,34]. In the period of 1900–1965 the close connection to mining shaped not only the area in a physical manner, as mining companies constructed and provided housing, but also had effects on the day to day life of residents and miners. Together with the Catholic Church, the mining industry had a big influence on how residents laid out their day to day lives in terms of work and leisure. The growth and prosperity began to decline after the coal mines were closed rapidly by the Dutch government in the period of 1965–1973. This closure was followed by many job losses, which impacted generations ahead, as well as population loss, which has manifested itself as selective outmigration of the young and qualified population through the years [38]. However, as Elzerman and Bontje [22] underline, the omission of the mining industry and the Church as institutions who influenced heavily how residents lived, was followed by socioeconomic consequences [14,28,34]. Not only did the unemployment rate skyrocket above national average [28], but residents were also left hanging, without major institutions telling them how to live and structure life. The governmental action against this trend was to transfer some national institutions, such as the national statistics office, a pension fund and the Open University to Heerlen. However, as Rocak [14] notes, this was a “clear mismatch between white and blue-collar employment”. Although the population has stabilized in recent years [33], Heerlen is still not considered a highly attractive city. Where mines and other built infrastructure were demolished, vacant green spaces were left and shape the cityscape together with vacant retail spaces in the inner city.

Figure 1.

Heerlen, The Netherlands. Own presentation.

2.2. Gebrookerbos to the Rescue

Today, many projects are implemented that focus on improving the quality of life in Heerlen and focus on young people and especially entrepreneurs to stay in the city and build their businesses. Other projects aim at stimulating the image of the city, such as the transformation of the area surrounding the main train station, called Maankwartier [34]. Further regeneration projects take place on a smaller scale and involve residents, such as Gebrookerbos, a project and method with the goal of reviving empty areas by citizens.

The long-term population loss in Heerlen has led to an oversupply of infrastructure, such as schools, kindergartens, residential and recreational buildings. Demolition, or right-sizing, of such infrastructure was a common strategy [39], has produced a plethora of empty spaces, which were not filled by market parties, such as investors or project developers. The idea of Gebrookerbos is a result of the collaboration between the municipality of Heerlen, the Open University as well as Neimed, a socio-economic knowledge institute [40]. It has been introduced by the municipality as a project “aimed at giving residents the space to contribute to bottom-up area development” [41] (p. 5). The overall goal with involving citizens within the Gebrookerbos project, was to improve the quality of life, especially in Heerlen Nord area, as the vacancy had started to create negative associations in the neighbourhoods as well as trigger nuisance. By implementing a ‘brooker’ as well as account managers, the direct relationship to citizens [41], who were given the opportunity to realize their ideas on these vacant spaces, the method Gebrookerbos was developed. Initiatives where focused on three topics: “urban agriculture”, “recreation” and “natural meeting” [40], with the intention to give new meaning to the spaces. Further, networking was set to be the goal as well as the method of Gebrookerbos; seen as an “acceleration room” [40] (p. 5), Gebrookerbos offered the necessary support and framework for cooperation between various actors.

3. Methodology

In light of the city as a complex system and the challenge of shrinkage, paired with differences in how problems are perceived differently by various members of society, this research takes a close look at the process and dynamics of change in governing shrinking cities. Particularly, the question of how these processes seem to trigger fundamental change in certain cities is a key point of interest. However, shrinking cities offer another layer of complexity to this question, as the “critical mass”—the creatives, the young and educated—is statistically showing a trend of leaving such cities.

The Gebrookerbos project represents a single case study which investigates the hindering and supportive factors of civic engagement in shrinking cities by tracing the process of how this project started, how it developed and the future prospects of the established initiatives. The question of “who” and “why” are therefore crucial points of departure for this research; Precisely, how change in governing shrinking cities is initiated, how it evolves and whether and how these changes contribute to a long-term adaptation of governance, or if increasing civic involvement is a stop-gap for municipal governments in shrinking cities. An in-depth case study research is therefore seen as a necessary method in order to grasp the nuanced manifestations of the case and reflect them against the specific circumstances where it takes place. This research does not produce generalizable evidence on how to involve citizens in shrinking cities but shows how the process was introduced in a post-mining town with long-term population loss.

The material included here are semi-structured in-depth interviews with involved stakeholders, such as the project manager, the brooker, two account managers, the monitoring researcher, as well as initiators of two citizens’ initiatives. Further, the analysis includes written material, such as publicly available project descriptions and reports. The interviews were chosen as primary data collection method for this research, as it investigates people’s behaviour, actions, perceptions and motivations. Statistical reports and descriptive information about the city are used as secondary data and not as an object of the investigation.

3.1. Data Collection

This research is conducted in a qualitative manner. A qualitative in-depth approach was chosen because the research is problem driven and looks for deeper understanding of civic engagement in a shrinking city. Data collection for this research largely relies on actor analysis. Actors were firstly identified through desk research and interviewed about their role and involvement in the process of Gebrookerbos as well as their views on shrinkage in general, in a second step. The respondents were limited to directly and indirectly (monitoring researcher) involved stakeholders in the project, representing the case study.

In the analysis part, involved actors are located on a grid that specifies their institutional embeddedness and role. The nature of the role is very much connected to the individual or group interest, the power influence but also resources that actors can utilize. This detailed actor analysis and the dynamics of their interactions with the focus on individual meaning-making and how certain actors view and order their worlds [42] is necessary in order to portray a proper contextualized picture of the situation.

3.2. Conducting Qualitative In-Depth Interviews and Restrictions

The in-depth interviews with involved actors were conducted in a semi-structured way. A pre-defined interview guide was leading the conversation and divided into four main blocks: personal background and information, perception of shrinkage, project specificities and governance change and lastly, outlook. The semi-structure of the guides was designed in a way that left enough time and space for the interviewees to tell their story freely. The first interviews in Heerlen were conducted face to face in the Neimed office, where the researcher spent her secondment during September and October 2020 and lasted up to two hours. Due to the critical situation of the COVID-19 pandemic at this time, the researcher proceeded with the data collection online, and interviews were conducted via Microsoft Teams and WhatsApp video. Those interviews lasted over one hour each; however, it has to be emphasized that conducting interviews in this setting had some minor negative effects on the interviewer’s side when it comes to interpreting body language. The digital room did feel artificially created and making the interview partner feel comfortable is thus a difficult task. In particular, proceeding with actor analysis of involved residents is challenging to perform online and it cannot be assumed that citizens have the equipment to meet in a digital space. Therefore, one interview has been conducted via WhatsApp video. Interviews have been recorded with the consent of the interviewee, transcribed and analysed by using the MaxQDA software.

4. Gebrookerbos: When Public Administrations Dare to Experiment in Shrinking Cities

In order to deal with the plethora of empty or unused areas in Heerlen which have been left over after the mines were closed, Gebrookerbos was initiated in 2014. Particularly the area around the North of the city “Heerlen Noord”, once the centre of the mines, is shaped by underused spaces. The population loss which followed the deindustrialization of the area led to the implementation of rightsizing policies to adjust the remaining built infrastructure to the current population size. At the core of the Gebrookerbos project was the idea to reuse those empty spaces. The following results are based on conducted interviews with officials at the municipality, such as the project manager and account managers, but also the brooker and one initiator of a citizens’ project under the Gebrookerbos umbrella, and one initiative that started before Gebrookerbos commenced, and is now part of it.

4.1. Open Spaces and Rest Areas: Opportunity Vs. Problem

The shutdown of the mining industry in the 1970s played a crucial part in the shrinking process of the city of Heerlen. Relying heavily on this one industry, an important part of the city’s identity fell apart. Not only did the end of the mining trigger a lot of unemployment, due to not providing enough substitute jobs that were fitting for the mining workers, but a large percentage of workers were left with health problems as well. “[…] people who were receiving social support from the municipality, this was around 50%. […] And this was very problematic. For the individual people, but also for their children. There was a whole generation that grew up with their father being unemployed and their grandfather not being able to work either” (Brooker, 2020). Therefore, many generations were affected by the closure of the industry, ultimately leading to selective outmigration due to no real perspectives in the city, leaving older generations behind. This in turn meant that a smaller population size was left and a plethora of built infrastructure was becoming obsolete. The municipality reacted with rightsizing policies to adjust the infrastructure to the smaller number of residents. “[…] there we saw a lot of schools that were closed and there was nothing left. Also for sport clubs; because of the shrinkage of the population also they needed to go together in one and leaving an empty place behind […]” (Project Manager, 2020).

However, the population loss and the challenges that followed, are not only seen as a problem. Rather, the municipality tries to highlight the opportunities that can come with the spaces that were left behind. Especially when it comes to civic participation, the municipality does acknowledge residents and their ideas for such spaces. “[…] shrinkage is for citizen participation a positive thing. Because we have a lot of space. And a lot of space where people can do things. It’s something which they are confronted with every day, so that’s when they ask for the municipality ‘Hey, we see these empty spaces, we have lots of ideas for that, can we do something about it?’” (Project Manager, 2020).

4.2. From Top-Down Steering to the (Arranged) Participation Society

In 2011 the municipality of Heerlen was confronted with ideas from citizens for the reuse of empty areas for the first time. However, participation and active citizenship was not always prominent in this area of the Netherlands. Power relations in the mining industry are being held accountable for the lack of participation until today. “Because working in the mines, there was the Big Boss and the mayor of the city and the head of Church. They had something to say. And the workers needed to keep their mouths shut and work. If they were critical, they would not only lose their job, but also their home. […] So the consequences were that people never stood up for their needs and concerns and were very passive when everything happened. And now, in the recent years, I think this is changing.” (Brooker, 2020).

Additionally, the famous King’s Speech of 2013, where the end of the welfare state was announced and citizens were called to participate in the provision of everyday services and shaping their neighbourhoods, triggered what is called the “participation society”. “Of course, 2013 […] on the commercials in TV there was always ‘The society—this is you!’ and it was always said that the people need to take responsibility for their own future […]. This has stimulated the awareness slowly.” (Brooker, 2020).

4.3. Selective Outmigration—Not Really A Problem for Civic Initiatives

While in theory older generations are not regarded as the critical mass for coming up with new and creative ideas, in Heerlen, shaped by the outmigration of the young and educated, creative ideas never came up short. However, the remaining younger population is interested in civic initiatives as well. “That was very different. The very first project […] these were older people. Proper mining workers. […] In this park, there’s younger ones, like 30, 35. And the one with the dogs, they are in the middle, like 50, 52, 53. All different layers of population […]. From 10,12 to 80, 85 years, that is a big range.” (Account Manager, 2021).

However, there is a tendency in terms of who actually starts the initiatives and who comes up with the first idea. Most of the time it is in fact older people who start the projects. “[…] they are the ones who comes up with the first idea. But we always say, you need to have a bigger layer of people who are connected, because otherwise it doesn’t work, and especially the younger people. You see that there’s always one citizen who is getting everything together, but around him there’s a mix of all kinds of people.” (Project Manager, 2020).

In fact, it was not the start of the Gebrookerbos project which triggered civic initiatives; they were already present before. However, most of the time they did not come into realization because the municipality did not know how to handle them. “[…] because we knew that there were citizens who had ideas, because it was started in 2010/11, when the first ideas came up” (Project Manager, 2020). Gebrookerbos created a fitting framework for the already existing ideas to reuse some empty areas: “We chose to start with them. We knew there were people with ideas, so we thought let’s start with them and see how we can facilitate as a municipality how to realize their ideas. And from those, I think we had three or four ideas, and from there on we grew further and further. […] we didn’t have a big poster ‘please come up with ideas’” (Project Manager, 2020).

4.4. Lack of Financial Resources as Trigger for Civic Involvement

With more and more buildings being torn down and open spaces emerging, the municipality realized that the area around Heerlen Noord needed restructuring to effectively deal with the situation. Restructuring typically falls under planning and is a top-down act; “But now, they said, we don’t have the money for this” (Brooker, 2020). One of the initial thoughts for restructuring was to experiment with a different type of municipal work. Since it was very clear from the beginning that the municipality would not be able to provide a new are plan that would accommodate the situation, civic participation came to mind. Two planning offices were hired, one from Rotterdam and one from Berlin, to brainstorm how the restructuring could work with the involvement of citizens. Here, the “Atlas Gebrookerbos” was developed in 2012, clearly stating that citizens would play an important role in the restructuring (Brooker, 2020). “[…] we cannot do it alone. […] as a municipality, we do not have the money to realize great parks in every open area. It’s not possible. It’s something that is necessary to do, because we cannot do it alone, we try to experiment with things. But also because the space is there to do it.” (Project Manager, 2020).

4.5. Policy Document Paves the Way for Experimental Governance

With the “Atlas Gebrookerbos” the strategy for area restructuring was developed by the municipality, Neimed and the Open University. The idea did come from the top. However, “[…] we knew there were people with ideas, so we thought let’s start with them. And see how we can facilitate as a municipality how to realize their ideas and from those, I think we have three or four ideas, and from then on we grew further and further.” (Project Manager, 2020).

Defining the strategy was a monumental point in the process; “We let go of the masterplan, you actually say ‘citizens, it’s up to you’” (Project Manager, 2020). From setting up a Gebrookerbos Funds to installing new positions in the municipality, the way of working had to change drastically within the municipality; however, it remained rather formal than informal. “It’s at formal level, so most of the time they do something on the ground that is owned by the municipality. So we need to make rules—not rules—but some things that you agree with each other. Who is going to do the maintenance […] and put that on a paper […]. This is what the municipality does, this is what you do as the citizens. And then we sign it.” (Project Manager, 2020).

This collaboration with citizens had one important underlying element that was necessary from both sides, trust. “[…] is there trust that inhabitants would give new functions to these areas and that the Gemeente is not so restricting […]. There are also some critical points when it comes to, okay, give them space, experiment, and don’t be so strict on regulations—this is still something difficult […].” (Monitoring researcher, 2020). However, to implement this new way of working in the municipality was not a smooth process at all. Not all colleagues agreed to bending rules for citizens. At this point, the role of the account managers was crucial. “[…] these Account Managers would say: ‘I know that these are the rules, but what are the other options?” (Monitoring researcher, 2020).

The role of Account Managers differs to a large extent from “regular” civil servants in the municipality. Particularly, understanding the mentality change and that experimenting with governance structures might provide something good for the municipality and for the citizens, was difficult to explain to long-established civil servants: “I was like … stop talking, and start doing. The citizens need something to be done, not us. […] It is difficult to change the thinking of people—my own colleagues!” (Account Manager, 2021).

4.6. The Role of the “Broker”and Skepticism towards the Municipality

Implementing a position as “brooker” was an absolutely crucial step in the process. More importantly, how this role was approached says a lot about the openness of the municipality towards experimental governance. “They asked me to do this project as brooker for Gebrookerbos. I didn’t know what this was. […] The interesting thing was that they couldn’t define very well what my role would be. I needed to discover this within the process, on my own” (Brooker, 2020). Although not many details about this role were clear in the beginning, it was understood that it was a different role than the one of the account managers. The brooker would be there for the process of initiation of the initiatives, a “pacemaker” (Account Manager, 2021) who would also help people put their ideas on paper and encourage them to go to the municipality. This brooker needed to be an independent person, not affiliated with the municipality, but also not with the social work profession for example, who is dependent on the municipality. So, the position of the brooker as an independent actor, who was employed by Neimed, was crucial for getting in touch with citizens. “They asked me in this one project […] ‘and you are working for the municipality?’—‘No, I don’t’—‘okay then, what can you do for us?’” (Brooker, 2020). This illustrates the scepticism of citizens towards the municipality. The brooker needed to be able to gain trust and let people know that they could contact him very informally if they needed some assistance with their initiative, or if they needed help with communicating with the municipality.

4.7. Shifting Responsibilities and Shortening the Distance between Citizens and Municipality

Apart from giving new life to unused spaces, the Gebrookerbos project had an important goal of shifting responsibilities within the city to show citizens that their ideas matter and joint collaboration can lead to great outcomes. Citizens would come up with ideas on their own, although sometimes there was a little help needed from the “brooker” to really get them going. “They could have their own ideas about it but also realize it so it could be something of their own and it could mean something for the neighbourhood […]” (Project Manager, 2020). Particularly in times of long-term shrinkage, loss of identity and population loss, the municipality realized that working on their own would not be possible on the scale that empty spaces were emerging in the city. It was a two-way street: letting go from the municipality’s side and stepping up from the citizen’s side.

Some citizens would not even get started with trying to realize their ideas, because they knew that there would be at least several people that they will be referred to, several forms they would need to fill out and they thought it could take even years of preparation and collection of all documents. The municipality of Heerlen knew that this was a common problem and if they wanted to focus on citizens, and needed their help, they would need to change internal ways of operating. This meant not only letting go of master planning, but not referring citizens to several departments and talking to a variety of civil servants. Instead, the role of account managers was implemented, and each civic initiative was assigned to one account manager who would guide them through the whole process. They would be the only contact point in the municipality that the citizens needed. “[…] when it comes to building processes in the municipality, it has definitely made it more accessible for citizens to conduct an initiative, absolutely.” (Monitoring Researcher, 2020).

4.8. It’s about the Process, Not the Project

When talking about Gebrookerbos, it is important to distinguish the process and the project. Although it was set up as a project that received funding and had a start and end date, Gebrookerbos was about creating a process and a method of working. The project officially ended in 2020, and project reports were published in 2021, but the method of working is still ongoing. The support of the “brooker” was also more oriented towards the process of the initiatives. “I think that the citizens, the initiatives, they liked it, that they had the responsibility, without somebody taking over or is playing the boss. […] It is a network where autonomy is very important, and working together. From the internal motivation and power, not due to formal agreements.” (Brooker, 2020).

Hence, the Gebrookerbos project, which received funding from the IBA as an initial step, was necessary to get the project going. However, the aim of the project was to develop a process, a method, that would continue long after the project is completed. This ultimately led to a policy being implemented in 2021 that states that urban planning projects will be conducted by starting on the very top of the participation ladder, meaning that citizens will take the lead. Only if this is not possible, will the municipality become more involved. “This is very risky to say that” […] I think they realized that the municipality is not Lord and Master over urban development. But also the people. […] This is an awareness.” (Brooker, 2020).

4.9. Conflicting Interests and Temporality Issues

While most of the initiatives were conducted in Heerlen Noord, there were also a few in the city centre, such as the “Stadstuin Heerlen”, a neighbourhood park in the heart of the city that emerged on an empty space. After tearing down a building, which stood empty for around ten years (Ellen, 2021), “[…] the Gemeente they put grass on it and some place to walk. […] And then we started with a group of 30 people and we said we can make a nice place of it. In the middle of the city. From my apartment I can look on that place” (Ellen, 2021). Office spaces and housing were supposed to be built; however, citizens had a different idea for this vacant space in the city centre. “The people were saying ‘we need to this here, it is a green part of town, it is a calm spot. We don’t need to put cement and concrete everywhere’. And from the municipality they were saying ‘no, we need to have a compact heart of the city and it needs to be built on’. That was a dilemma.” (Brooker, 2020).

However, the success of Stadstuin made the municipality realize the importance of these initiatives: “they see what it does with people. The people connect. It’s for all people. We have a better position and they listen to us. They listen to the people in Heerlen.” (Ellen, 2021).

While many initiatives were implemented on grounds that would not be built on for some time, other terrains were already planned to be developed. In the case of Stadstuin it was made clear that if there would be interest from investors to build on these grounds, the initiatives would have to give way to those. “[…] to be very clear to initiatives to say okay, this is something temporary […]” (Monitoring researcher, 2020). However, Stadstuin, as well as Dobbletuin, the two initiatives interviewed for this analysis, were able to persevere. For Stadstuin, although the apartments are going to be built, the initiative is included in the plan: “it still will be a green place and we can have that place to do our stuff in the future” (Ellen, 2021).

4.10. A Plethora of Funding Pools to Ensure Longevity

The question of longevity of these initiatives accompanied the project from the beginning. Although “[…] we even saw that money is not even the most important thing, because they will find their way. […] We started Gebrookerbos funding and there was 200.000 in it. We started in June 2018, so we have it for a while, but I think 100.000 Euros now is spent and the other half not” (Project Manager, 2020). Apart from the Gebrookerbos funding, and the IBA funding, a national funding pool “VSB” was made available, who continue to support civic initiatives in the country. Additionally, “Frisse Wind” was introduced as a framework for distributing the donations from VSB. Further, two follow-up projects were implemented to ensure the continuation of the method in Heerlen. The first one, “Stadslab Heerlen”, an urban laboratory for creatives and artists who, with the help of a brooker, can find vacant spaces for their initiatives while using the Gebrookerbos method. The second, “N-Power”, is an international project between Belgium, Germany and The Netherlands with a focus on civic initiatives. There, initiators of projects in Heerlen get the chance to talk about and present their initiatives and learn from each other (Brooker, 2020).

4.11. Citizens on Their Own: Informality Works

While Gebrookerbos was initiated in 2014, there were already civic initiatives existing in Heerlen, such as Dobbletuin that were successful on their own. A privately owned, empty green area was supposed to be developed and housing was about to be built, without having a concrete time frame yet. Active citizens, who had the idea of creating a social meeting place paired with a fruit and vegetable garden, directly approached the owner who “was just the right person […] and he also had a botanic garden and he had an open mind. […] He said I don’t know what the directory will think about it, but it was still the time where they had no plans for it” (Leo, 2021). “We don’t have a contract […] I say, we have still eight years. But I don’t know how long [..] I will have the energy […]” (Leo, 2021).

The Dobbletuin initiative shows, that temporary use was also possible without the formal frame of Gebrookerbos. However, it is easier than doing it on your own, as the initiator underlines “If you have an idea and you don’t know how and which way you want to go, then it is easy to have an address. There are people who can help you further.” (Leo, 2021). Additionally, the Dobbletuin initiative had immense luck to have agreed with the landowner on such good terms and was able to be realized very quickly as the formalities were not taken too seriously by both parties.

5. Gebrookerbos: Roles and Influences

After the actors have been identified and interviewed, several forms of their involvement became apparent. In Table 1 these actors are located on a grid to illustrate them in a simple way. Actors have been classified according to their institutional embeddedness, such as being a private or public actor, and intermediary or individual actor. Their role and influence have been divided into human and cultural capital, or ideas, policy making, monetary, facilitating and lastly, proactively stimulating. The former combines human and cultural capital as well as ideas that the respective actors come up with. It encompasses any skills and knowledge, particularly about the city of Heerlen and its identity. Further, any knowledge which can bring benefits to social relationships as well as simply ideas about how to start an initiative, how to realize it, which people need to be involved and so on. Policy-making summarizes the formal making of policies, putting them onto political agendas and implementation. Monetary influence is understood as actors being able to steer decisions due to having a say in the distribution of funds or being the sponsor themselves. The role of facilitating is a particular one, as it not only encompasses the facilitation of for example conversation between formal and informal actors, but also being a facilitator due to other reasons, such as creating a framework for developing ideas, being open to new processes and so on. Finally, proactively stimulating means actors who are driven by the intrinsic motivation to get their ideas and beliefs through.

Table 1.

Involved actors and their roles. Own presentation.

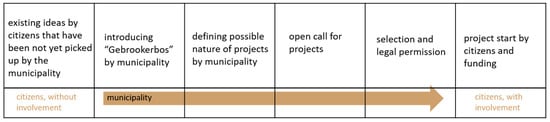

As this research is also concerned with the processual character of the change in governance, the collected data from the interviews have been put into a rough timeline.

Figure 2 illustrates roughly at what point citizens actually came into play in Gebrookerbos. Together with Table 1 it becomes clear that the municipality’s involvement in the process is the major one, and citizens in fact play a minor role in decision-making. Rather, they become the main actor by trying to realize their ideas, and only if they act proactively themselves. Further, as can be seen in Table 1, the role and influence of the municipality ranges from coming up with ideas, such as Gebrookerbos itself, to policy-making and adapting policies to accommodate the initiatives, to monetary resources as they set up the Gebrookerbos Funds. The municipalities’ role as facilitator is an interesting one, as without them, the already existing ideas of citizens would not be picked up at all. This also coincides with their role as a proactive stimulant.

Figure 2.

Timeline of citizen involvement. Own presentation.

6. Discussion

In the aspect of civic involvement, the Netherlands are often seen as forerunner. Flexible approaches and letting go of intense bureaucratic processes and rigid rules are one factor in making the participation society possible. On the other hand, the willingness of individual citizens to contribute and shape their neighbourhoods is needed. This trend towards a “smaller government” and “active citizenship”, towards governing urban development with or by citizens, has not skipped the shrinking city of Heerlen, Netherlands. The example of Gebrookerbos highlights the complexity of the relationship between the municipality and citizens within the existing governance of the city. However it also highlights that the existing governance [31] and the participation culture as well as historic events, such as the rapid closure of mines, have effects on the success of projects such as Gebrookerbos.

As the Project Manager stressed, not only was the financial situation a reason for starting this experiment of involving citizens, but the space that was created by the shrinking process offered the physical possibility to try such a new process. The recognition of shrinkage as a possibility for non-profitable civic initiatives shows clearly, that the municipality is not afraid of acknowledging shrinkage, and using this development for improving the quality of life. This is in line with what Oswalt [7] calls “weak planning”, or Elzerman and Bontje [34] refer to as “alternative planning”. Focusing on soft tools, such as empowerment of citizens and communication, rather than traditional planning processes, can be a possible way forward for shrinking cities and foster a change in perception and attitude. As Dax and Fischer [43] conclude as well, regional development of shrinking areas has to move away from economic growth and focus on local strategies, involving citizens or experimenting with social innovation.

Additionally, letting go of the masterplan and exploring more informal ways of urban development, is very much in line with accepting and utilizing the uncertainty that comes with shrinkage. In Heerlen, planning beyond “the plan” [11] seems to have arrived, although the lack of financial and institutional capacity is very much seen as trigger for this extensive civic engagement as well. This finding corresponds with the argument that challenges of shrinkage can lead to a planning vacuum, which can stimulate civic engagement [16].

The timeline shows that before Gebrookerbos was initiated, civic initiatives for reusing the empty areas were acknowledged, but not considered further. This shows how even in long-term shrinking cities, as Heerlen is considered, the adaptation of rigid bureaucracy and the implementation of experimental governance, is not easy. The administration was shaped by long processes and multiple people who referred citizens to one another, and it took a lot of convincing to let go of traditional ways of governing. The new roles of Account Managers, who would be the only contact person within the municipality for citizens, was crucial to shorten the method of communication and get initiatives implemented much quicker. It also played a key role in how citizens viewed the municipality in a new light. They were not seen as the difficult actor, but actually approachable people who can get things done. In accordance with Ročak [14], who concludes that “involving civil society is easier said than done” (p. 715), the example of Heerlen shows exactly that. Even after providing a formal frame, funding and extensive assistance by the brooker as well as account managers, scepticism towards the municipal government is still present. This is why trust plays a crucial role and has to be addressed proactively [43].

Ubels et al. [30] emphasize in their study how important the role of brookers as knowledge facilitators is. The findings in this research agree with this conclusion, however it has to be stressed that the key factor here was the fact that the brooker was an independent actor and not affiliated with the municipality. The brooker almost played a role of translator between citizens and municipality. Having such an intermediary person in the governance arrangement of Gebrookerbos broke down barriers that existed due to the bureaucratic past. The brooker also acted as a so-called pace-maker, making sure citizens stayed on top of their initiatives and trying to get them moving towards realizing their ideas.

However, as the timeline shows, there were already citizens who had ideas for unused plots before Gebrookerbos started and that there were also initiatives that were successful in using vacant spaces informally, without the Gebrookerbos framework. However, the latter constitute the minority and the plethora of initiatives realized under the Gebrookerbos umbrella shows that governmental involvement in stimulating civic engagement is necessary. In line with the findings of Ubels et al. [29], the support from the government is seen as crucial in the Gebrookerbos project. In particular, in cities with a contested past of participation and no tradition of self-organization and involvement, such as Heerlen, simply asking for engagement does not work. Nevertheless, it also has to be addressed critically that although Gebrookerbos is supposed to give citizens the leading role, they are only involved at a rather late stage in the whole process. For example, the nature of the initiatives was defined by the municipality and several initiatives could not fit into what the municipality had envisioned.

7. Concluding Remarks

Shrinkage is a well-known topic in Heerlen, Netherlands. The city has been losing population for a long time and has stabilized very recently. The industrial past has shaped not only the physical urban environment but has also had effects on the participation culture. Although citizens had ideas for initiatives before Gebrookerbos commenced, the project definitely contributed to increasing their involvement by providing a framework for initiating projects. This research analysed how governance processes and structures have changed since the introduction of the “Gebrookerbos” project. It argues that in order to revive shrinking cities into sustainable places, work on the hardware and software need to go hand in hand. The transformation and reinvention of the participation process has been adapted in order to provide space for real active engagement by residents, by: (1) shortening the way from citizen to municipality through implementing account managers; (2) implementing a brooker role as independent actor to gain trust; (3) giving citizens the lead in realizing their initiatives; and (4) letting go of the masterplan. These steps are seen as crucial in the case of Heerlen and have contributed to the reuse and temporary use of vacant green spaces as well as improving the contested relationship between city administration and citizens.

Further, the findings show that governing the reuse of empty green spaces is a task a municipality of a shrinking city cannot tackle on their own. Citizens play a crucial role and, although the Heerlen case shows how they have been considered in a strategic way, there could be more flexibility for such initiatives. In cities which have a more developed participation culture, a more open process can be considered. Nevertheless, such temporary projects need to be handled with care in shrinking cities. As Dubeaux and Cunningham-Sabot [10] underlined, such approaches can be used or exploited to maximize land value. The two initiatives interviewed for this research show that this does not have to be the case. These initiatives started as temporary projects and have been existing for several years now and are bringing people together, providing a social meeting place.

This study further shows the need to focus on residents, on the “software” and on “alternative planning” strategies in shrinking cities. The vacant areas in the city of Heerlen constitute a challenge, however it is not the only one. Residents have been complaining about the degradation of neighbourhoods and the loss of quality of life due to nuisance in these areas. The Gebrookerbos method successfully stimulates the “software” of the city, by facilitating civic empowerment, providing channels for engagement and communication, and simultaneously improves the “hardware”, the visible vacancy and degradation of empty areas. Therefore, this research concludes that strategies in shrinking cities do not have to focus on either hardware or software but they can go hand in hand.

Funding

This research has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Marie Skłodowska Curie grant agreement No. 813803.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Martinez-Fernandez, C.; Audirac, I.; Fol, S.; Cunningham-Sabot, E. Shrinking Cities: Urban Challenges of Globalization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Großmann, K.; Bontje, M.; Haase, A.; Mykhnenko, V. Shrinking cities: Notes for the further research agenda. Cities 2013, 35, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospers, G.-J. Policy Responses to Urban Shrinkage: From Growth Thinking to Civic Engagement. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1507–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, S.; Pinho, P. Planning for Shrinkage: Paradox or Paradigm. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turok, I.; Mykhnenko, V. The trajectories of European cities, 1960–2005. Cities 2007, 24, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A.; Nelle, A.; Mallach, A. Representing urban shrinkage—The importance of discourse as a frame for understanding conditions and policy. Cities 2017, 69, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswalt, P. (Ed.) Shrinking Cities Vol 1: International Research, 1st ed.; Hatje Cantz: Ostfildern, Germany, 2005; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bueren, E.M. Dealing with Wicked Problems in Networks: Analyzing an Environmental Debate from a Network Perspective. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2003, 13, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, K.; Haase, A. Neighborhood change beyond clear storylines: What can assemblage and complexity theories contribute to understandings of seemingly paradoxical neighborhood development? Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubeaux, S.; Cunningham-Sabot, E. Maximizing the potential of vacant spaces within shrinking cities, a German approach. Cities 2018, 75, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, L.; de Roo, G. Planning of undefined becoming: First encounters of planners beyond the plan. Plan. Theory 2014, 15, 42–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauws, W. Embracing Uncertainty Without Abandoning Planning. disP Plan. Rev. 2017, 53, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roo, G. Being or Becoming? That is the Question! In Confronting Complexity with Contemporary Planning Theory; A Planner’s Encounter with Complexity; de Roo, G., Silva, E.A., Eds.; Ashgate: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ročak, M. Perspectives of civil society on governance of urban shrinkage: The cases of Heerlen (Netherlands) and Blaenau Gwent (Wales) compared. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 699–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyushkina, A. “Force Majeure”: The Transformation of Cultural Strategy as a Result of Urban Shrinkage and Economic Crisis. The Case of Riga, Latvia. Urbana 2021, 22, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, M. Community-Led, Government-Fed, and Informal. Exploring Planning from Below in Depopulating Regions across Europe; Proefschriftmaken.nl: Vianen, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hospers, G.-J.; Syssner, J. (Eds.) Dealing with Urban and Rural Shrinkage: Formal and Informal Strategies; Lit: Zürich, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ročak, M.; Hospers, G.-J.; Reverda, N. Civic action and urban shrinkage: Exploring the link. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2016, 9, 406–418. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, A.; Hospers, G.-J.; Pekelsma, S.; Rink, D. Shrinking Areas. Front-Runners in Innovative Citizen Participation; European Urban Knowledge Network: Hague, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hospers, G.-J. Coping with Shrinkage in Europe’s cities and towns. Urban Des. Int. 2013, 18, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlappa, H. Co-producing the cities of tomorrow: Fostering collaborative action to tackle decline in Europe’s shrinking cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2017, 24, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, M.; Haase, A.; Großmann, K.; Cocks, M.; Couch, C.; Cortese, C.; Krzysztofik, R. How does(n’t) Urban Shrinkage get onto the Agenda? Experiences from Leipzig, Liverpool, Genoa and Bytom. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1749–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallagst, K.E.A. (Ed.) The Future of Shrinking Cities: Problems, Patterns and Strategies of Urban Transformation in a Global Context; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Radzimski, A. Changing policy responses to shrinkage: The case of dealing with housing vacancies in Eastern Germany. Cities 2016, 50, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiechmann, T.; Bontje, M. Responding to Tough Times: Policy and Planning Strategies in Shrinking Cities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2013, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audirac, I. Introduction: Shrinking Cities from marginal to mainstream: Views from North America and Europe. Cities 2018, 75, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemschat, N. Refugee Arrival under Conditions of Urban Decline: From Territorial Stigma and Othering to Collective Place-Making in Diverse Shrinking Cities? Sustainability 2021, 13, 13301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ročak, M.; Hospers, G.-J.; Reverda, N. Searching for Social Sustainability: The Case of the Shrinking City of Heerlen, The Netherlands. Sustainability 2016, 8, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubels, H.; Bock, B.B.; Haartsen, T. The Dynamics of Self-Governance Capacity: The Dutch Rural Civic Initiative ‘Project Ulrum 2034’. Sociol. Rural. 2019, 59, 763–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubels, H.; Bock, B.; Haartsen, T. An evolutionary perspective on experimental local governance arrangements with local governments and residents in Dutch rural areas of depopulation. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2019, 37, 1277–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A.; Bernt, M.; Großmann, K.; Mykhnenko, V.; Rink, D. Varieties of shrinkage in European cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2016, 23, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, D. Wilderness: The Nature of Urban Shrinkage? The Debate on Urban Restructuring and Restoration in Eastern Germany. Nat. Cult. 2009, 4, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBS: Statline. Available online: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/en/ (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Elzerman, K.; Bontje, M. Urban Shrinkage in Parkstad Limburg. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekveld, J.J.; Bontje, M. Intra-Regional Differentiation of Population Development in Southern-Limburg, the Netherlands. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2016, 107, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, M.S. Iconic Architecture and Middle-Class Politics of Memory in a Deindustrialized City. Sociology 2020, 54, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanHoose, K.; Hoekstra, M.; Bontje, M. Marketing the unmarketable: Place branding in a postindustrial medium-sized town. Cities 2021, 114, 103216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latten, J.; Musterd, S. (Eds.) De nieuwe Groei Heet Krimp: Een Perspectief Voor Parkstad Limburg; Nicis Institute: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bernt, M. Partnerships for Demolition: The Governance of Urban Renewal in East Germany’s Shrinking Cities. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 754–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimed. Rapport Methodische beschrijving Gebrookerbos. Een Werkwijze voor Bottom-Up Gebiedsontwikkeling in Krimpgebieden; Neimed: Heerlen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Neimed. Rapport Indicatieve MKBA Gebrookerbos 1. Een Onderzoek Naar Het Maatschappelijk Rendement van Drie Burgerinitiatieven in Heerlen-Noord; Neimed: Heerlen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yanow, D. Conducting Interpretive Policy Analysis; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dax, T.; Fischer, M. An alternative policy approach to rural development in regions facing population decline. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).