Social Cost-Benefit Analysis of Bottom-Up Spatial Planning in Shrinking Cities: A Case Study in The Netherlands

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Regeneration of Shrinking Cities

2.2. Citizen Involvement: Advantages and Challenges

2.3. Social Cost-Benefit Analysis (SCBA)

3. Methods & Study Setting

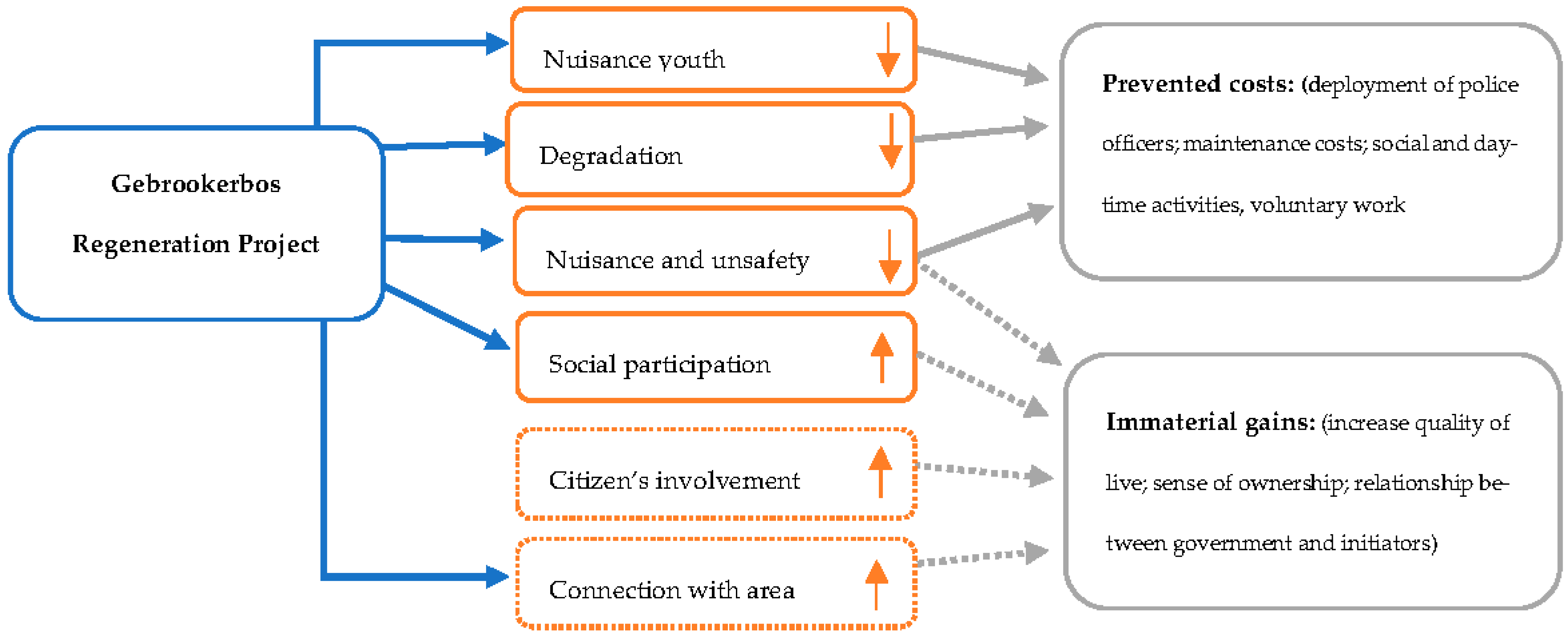

3.1. Gebrookerbos Project Description

3.2. Gebrookerbos as a Regeneration Project: A Bottom-Up Approach

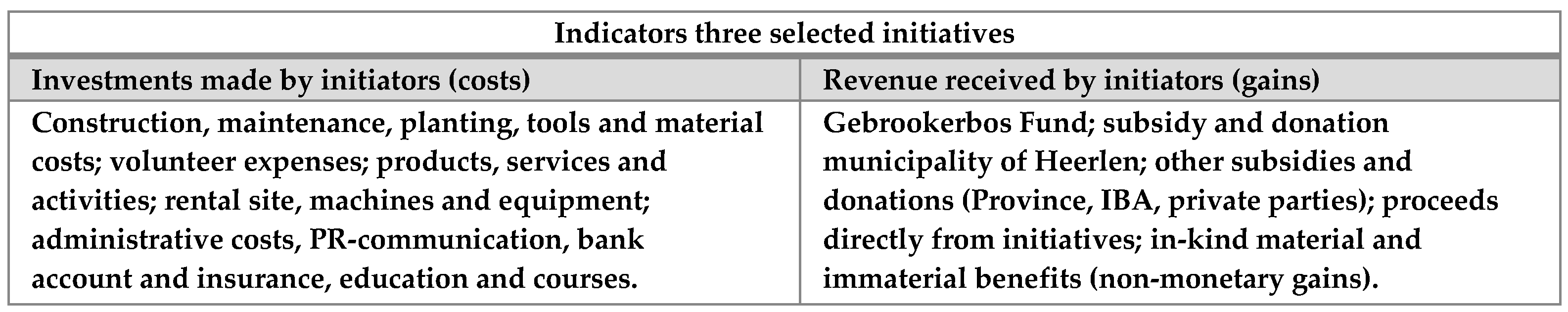

3.3. Method: Indicative SCBA Gebrookerbos

4. Results and Discussion

Results SCBA Gebrookerbos

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haase, A.; Rink, D. Analysis: Protest, participation, empowerment. Civic engagement in shrinking cities in Europe: The example of housing and neighbourhood development. In Shrinking Areas: Front-Runners in Innovative Citizen Participation; Haase, A., Hospers, G.-J., Pekelsma, S., Rink, D., Eds.; European Urban Knowledge Network: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 29–40. ISBN 978-94-90967-06-2. [Google Scholar]

- Reverda, N. Regionalisering en Mondialisering; Eburon: Delft, The Netherlands, 2004; ISBN 90 5972 018 0. [Google Scholar]

- Ročak, M. Perspectives of civil society on governance of urban shrinkage: The cases of Heerlen (Netherlands) and Blaenau Gwent (Wales) compared. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 27, 699–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubels, H. Novel Forms of Governance with High Levels of Civic Self-Reliance. Doctoral Dissertation, Groningen University, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tonkens, E.; Verhoeven, I. Bewonersinitiatieven: Proeftuin voor Partnerschap Tussen Burgers en Overheid; Pallas Publications: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 90 8555 060 2. [Google Scholar]

- WRR. Vertrouwen in Burgers; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 978 90 8964 404 6. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Chin, S.Y.W. Assessing the effectiveness of public participation in neighbourhood planning. Plan. Pract. Res. 2013, 28, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carp, J. Wit, style, and substance: How Planners Shape Public Participation. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2004, 23, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Newman, G.; Jiang, B. Urban Regeneration: Community Engagement Process for Vacant Land in Declining Cities. Cities (Lond. Engl.) 2020, 102, 102730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moniz, G.C.; Andersson, I.; Hilding-Hamann, K.E.; Mateus, A.; Nunes, N. Inclusive Urban Regeneration with Citizens and Stakeholders: From Living Labs to the URBiNAT CoP. In Nature-based Solutions for Sustainable Urban Planning. Contemporary Urban Design Thinking; Mahmoud, I.H., Morello, E., Lemes de Oliveira, F., Geneletti, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 105–146. ISBN 978-3030895242. [Google Scholar]

- Ročak, M.; Reverda, N.; Hermans, H. People’s Climate in Shrinking Areas: The Case of Heerlen, The Netherlands: How Investing in Culture and Social Networks Improves the Quality of Life in Shrinking Areas. In Demographic Change and Local Development: Shrinkage, Regeneration and Social Dynamics; Martinez-Fernandez, C., Kubo, N., Noya, A., Weyman, T., Eds.; OECD: Paris, France, 2012; pp. 249–256. ISSN 2079-4797. [Google Scholar]

- Ročak, M. The Experience of Shrinkage Exploring Social Capital in the Context of Urban Shrinkage. Ph.D. Thesis, Radboud University Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Westerink, J.; Salverda, I.; Van der Jagt, P.; Breman, B. Burgerkracht bij Krimp!: Wat Kunnen en Willen Bewoners Doen in het Beheer van de Openbare Ruimte; Wageningen UR/Alterra: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- De Rijk, M. Maak van bewonersinitiatieven geen beleidsinstrument; Sociale Vraagstukken, 2016. Available online: http://www.socialevraagstukken.nl/maak-van-bewonersinitiatieven-geen-beleidsinstrument (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- Van de Wijdeven, T.M.F. Doe-Democratie: Over Actief Burgerschap in Stadswijken; Eburon: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Steen, M.; Hajer, M.; Scherpenisse, J.; van Gerwen, O.J.; Kruitwagen, S. Leren door doen: Overheidsparticipatie in een energieke samenleving; NSOB: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dohmen, J. Vertrouwen in Burgers; Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lamein, A. Vertrouwen in de Buurt; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Graaf, P.; Duyvendak, J.W. Thuis voelen in de buurt: Een opgave voor stedelijke vernieuwing Een vergelijkend onderzoek naar de buurthechting van bewoners in Nederland en Engeland; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, L.C.; Perkins, D.D. Finding Common Ground: The Importance of Place Attachment to Community Participation and Planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2006, 20, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Louali, S.; Ročak, M.; Stoffels, J. Methodische Beschrijving Gebrookerbos: Een werkwijze voor bottom-up gebiedsontwikkeling in krimpgebieden; Neimed: Heerlen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Louali, S.; Reverda, N.; Van der Luitgaarden, G. Wijkmonitor Gebrookerbos 2015–2016: De Sociale Vitaliteit van Heerlen-Noord in Beeld Gebracht; Neimed: Heerlen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Turok, I.; Mykhnenko, V. The trajectories of European cities, 1960–2005. Cities 2007, 24, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.; Wiechmann, T. Urban growth and decline: Europe’s shrinking cities in a comparative perspective 1990–2010. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2017, 25, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham-Sabot, E.; Roth, H. Growth paradigm against urban shrinkage: A standardized fight? The cases of Glasgow (UK) and Saint-Etienne (France). In Shrinking Cities. International Perspectives and Policy Implications; Pallagst, K., Wiechman, T., Martinez-Fernandez, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781138952874. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, W.; Deng, J.; Xun, L. Identification of “Growth” and “Shrinkage” Pattern and Planning Strategies for Shrinking Cities Based on a Spatial Perspective of the Pearl River Delta Region. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aber, J.; Yahagi, H. Emerging regeneration strategies in the US, Europe and Japan. In Shrinking Cities: International Perspectives and Policy Implications; Pallagst, K., Wiechman, T., Martinez-Fernandez, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781138952874. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Fernandez, C.; Audirac, I.; Fol, S.; Cunningham-Sabot, E. Shrinking Cities: Urban Challenges of Globalization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welling, B.; Feijen, H.; Van Engelen, J. Wijkontwikkeling op Eigen Kracht; Landelijk Samenwerkingsverband Aandachtswijken (LSA): Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hospers, G.J. Policy responses to urban shrinkage: From growth thinking to civic engagement. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1507–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastaldi, F. Event-based urban regeneration and gentrification in the historic centre of Genoa. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2013, 7, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Camerin, F. From “Ribera Plan” to “Diagonal Mar”, passing through 1992 “Vila Olímpica”. How urban renewal took place as urban regeneration in Poblenou district (Barcelona). Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ročak, M.; Hospers, G.-J.; Reverda, N. Searching for social sustainability: The case of the shrinking city of Heerlen, The Netherlands. Sustainability 2016, 8, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Dam, R.; Salverda, I.; During, R. Effecten van Burgerinitiatieven en de rol van de Rijksoverheid; Alterra/Wageningen UR: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 9789461730879. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, H.; Hultkrantz, L.; Lindberg, G.; Nilsson, J.E. Application of BCA in Europe—Experiences and challenges. J. Benefit Cost Anal. 2018, 9, 120–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mouter, N. The politics of cost-benefit analysis. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romijn, G.; Renes, G. Algemene Lijddraad voor Maatschappelijke Kosten-Batenanalyse; CPB/PBL: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, V.; De Boer, L. Werken aan Maatschappelijk Rendement: Een Handleiding voor Opdrachtgevers voor MKBA’s in het Sociaal Domein; Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman, F.; Heinzerling, L. Priceless: On Knowing the Price of Everything and the Value of Noting; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 1-56584-850-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kruiter, H.; Kruiter, A.J.; Blokker, E. Hoe Waardeer je een Maatschappelijk Initiatief: Handboek voor Publieke Ondernemers; Wolters Kluwer: Deventer, The Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 9789013133486. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, C.; Tait, M. The Crisis of Trust and Planning. Plan. Theory Pract. 2007, 8, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooiman, J. Modern Governance: New Government Society Interactions; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1993; ISBN 9781849207119. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, R. The New Governance: Governing without Government. Political Stud. 1996, 44, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meerkerk, I. Top-down Versus Bottom-up Pathways to Collaboration between Governments and Citizens: Reflecting on Different Participation Traps. In Collaboration and Public Service Delivery: Promise and Pitfalls; Kekez, A., Howlett, M., Ramesh, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 149–167. ISBN -978-1-78897-857-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pissourios, I.A. Top-down and Bottom-up Urban and Regional Planning: Towards a Framework for the Use of Planning Standards. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy. 2014, 21, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Planning Through Debate: The Communicative Turn in Planning Theory. In The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning, Fischer, F., Forester, J., Eds.; Duke Univeristy Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 233–253. ISBN 9780822381815. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Social Systems; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 9780804726252. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans, C.; Heyma, A.; Hof, B.; Imandt, M.; Kok, L.; Pomp, M. Werkwijzer voor Kosten-Batenanalyse in het Sociale Domein; SEO Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; ISBN 978-90-6733-805-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gemeente Heerlen. Evaluatie Onderzoek Gebrookerbos; Gemeente Heerlen: Heerlen, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Louali, S.; Ročak, M. Wijkmonitor Gebrookerbos 2016–2017: De Sociale Vitaliteit van Heerlen-Noord in Beeld Gebracht; Neimed: Heerlen, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, P. The Evolution, Definition and Purpose of Urban Regeneration Urban Regeneration Handbook; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, V. Co-Production and Collaboration in Planning—The Difference. Plan. Theory Pract. J. 2014, 15, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R. Sense of place in a development context. J. Environ. Psychol. 1998, 18, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankel, S. The importance of open spaces in the urban pattern. In Cities and Spaces: The Future Use of Urban Spaces; Wing, L., Ed.; Hopkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1963; ISBN 0801806771-9780801806773. [Google Scholar]

- Penninx, K. Succesvolle Burgerinitiatieven in Wonen, Welzijn & Zorg. Available online: https://www.movisie.nl/sites/default/files/Artikel6-Als-het-geld-rolt.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Louali, S.; Ročak, M.; Stoffers, J. Indicatieve MKBA Gebrookerbos: Een onderzoek naar het maatschappelijk rendement van drie burgerinitiatieven in Heerlen-Noord; Neimed: Heerlen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Masterson, D.T.R. Network Recruitment Experiments: Causal Inference in Social Networks and Groups of Known or Unknown Network Structure. Working Paper; Yale University: New Haven, CT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogeboom, B. Sociaal Ondernemerschap is Meer dan Nodig. Available online: https://www.socialevraagstukken.nl/sociale-problemen-hebben-sociaal-ondernemerschap-nodig (accessed on 14 September 2018).

- Hillen, M.; Panhuijsen, S.; Verloop, W. Iedereen Winst: Samen met de Overheid naar een Bloeiende Social Enterprise Sector; Social Enterprise NL: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, N. The role, organisation and contribution of community enterprise to urban regeneration policy in the UK. Prog. Plan. 2012, 77, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, S.; Reverda, N.; Van der Wouw, D. Randland. Rooilijn 2015, 48, 272–279. Available online: http://archief.rooilijn.nl/download?type=document&identifier=586510 (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- Reverda, N. Krimp als Werkend Perspectief: Enkele Reflecties naar Aanleiding van de Vijfde Neimed Krimplezing; Neimed: Heerlen, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Louali, S.; Ročak, M.; Stoffers, J. Social Cost-Benefit Analysis of Bottom-Up Spatial Planning in Shrinking Cities: A Case Study in The Netherlands. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116920

Louali S, Ročak M, Stoffers J. Social Cost-Benefit Analysis of Bottom-Up Spatial Planning in Shrinking Cities: A Case Study in The Netherlands. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116920

Chicago/Turabian StyleLouali, Samira, Maja Ročak, and Jol Stoffers. 2022. "Social Cost-Benefit Analysis of Bottom-Up Spatial Planning in Shrinking Cities: A Case Study in The Netherlands" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116920

APA StyleLouali, S., Ročak, M., & Stoffers, J. (2022). Social Cost-Benefit Analysis of Bottom-Up Spatial Planning in Shrinking Cities: A Case Study in The Netherlands. Sustainability, 14(11), 6920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116920