“I Am Here to Fly, but Better Get the Environment Right!” Passenger Response to Airport Servicescape

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Airport Servicescape

2.1.1. The Substantive Staging of the Airport Servicescape (SSoS)

2.1.2. The Communicative Staging of the Airport Servicescape (CSoS)

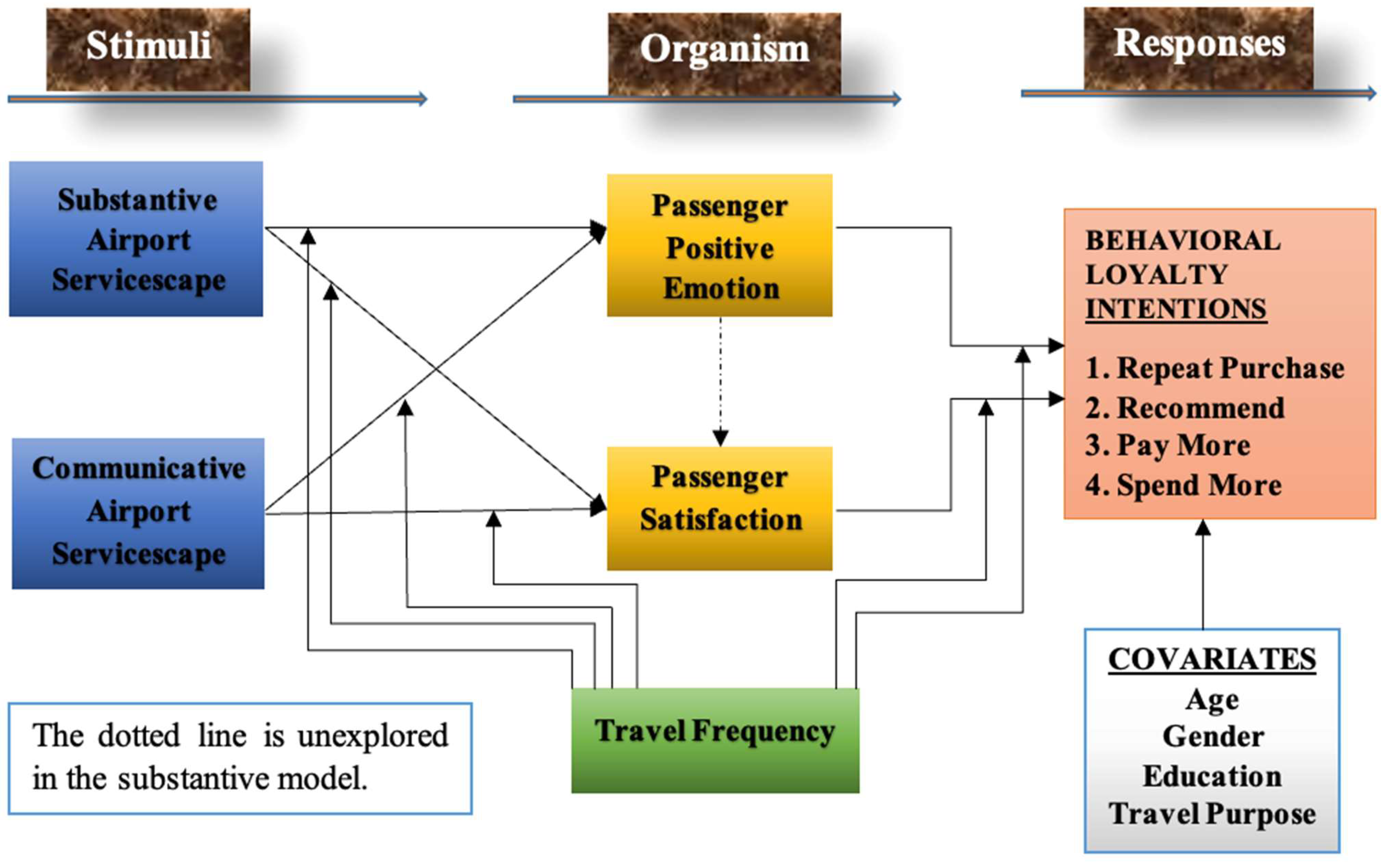

3. Research Framework and Hypotheses Formulation

3.1. Theoretical Framework: Stimuli–Organism–Response (SOR)

3.2. Research Hypotheses

3.2.1. The Effects of Airport Servicescape (i.e., SSoS and CSoS) on Passengers’ Positive Emotion and Satisfaction

3.2.2. Interrelations between Positive Emotion, Satisfaction, and Behavioral Intentions

3.2.3. The Moderation Effect of Passengers’ Travel Frequency

4. Research Methods

4.1. Study Setting, Participants and Procedure

4.2. Measurement Scales

4.3. Analytic Technique

5. Results

5.1. Data Preparation

5.2. Measurement Model

5.2.1. Confirmatory Factory Analysis

5.2.2. Validity and Reliability Assessment

5.3. Hypotheses Testing

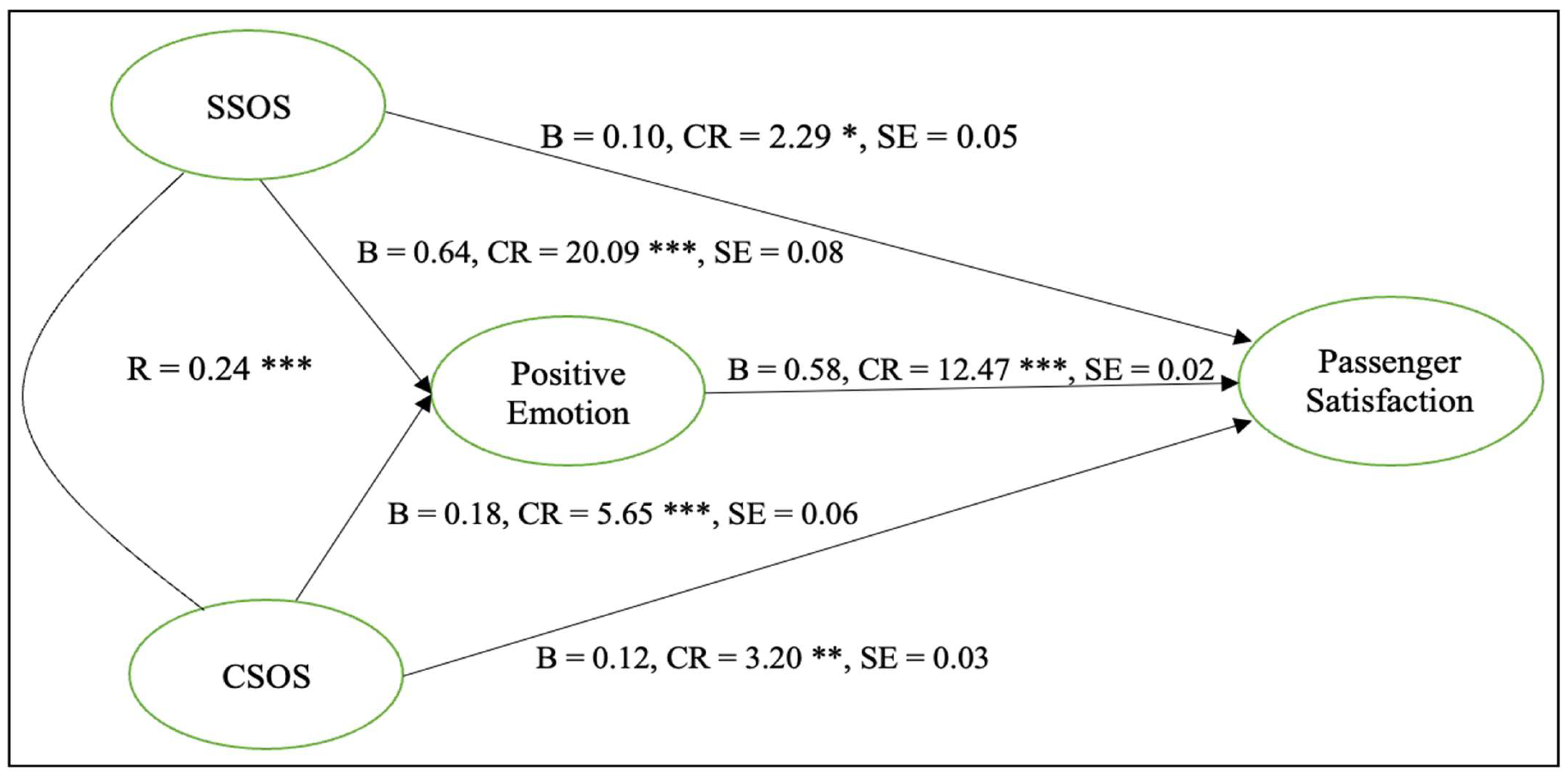

5.3.1. The Association among SSoS, CSoS, Passengers’ Emotion, and Satisfaction

5.3.2. Passengers’ Emotion and Satisfaction as Predictors of Behavioral Intentions

5.3.3. Moderating Effect of Travel Frequency on the Influence of Airport Servicescape (i.e., SSoS and CSoS) on Passenger (a) Positive Emotion and (b) Satisfaction

5.3.4. Moderating Effect of Travel Frequency on the Influence of Passenger (a) Positive Emotion and (b) Satisfaction on Behavioral Intensions

5.4. Post Hoc Analysis

6. Discussion

6.1. Results Summary

6.2. Theoretical Implication

6.3. Practical Implication

6.4. Limitations and Avenues for Further Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duleba, S.; Moslem, S. Sustainable Urban Transport Development with Stakeholder Participation, an AHP-Kendall Model: A Case Study for Mersin. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Moslem, S.; Blaschke, T.; Duleba, S. Sustainable Urban Transport Planning Considering Different Stakeholder Groups by an Interval-AHP Decision Support Model. Sustainability 2018, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, C.O.; Fan, C.-J.; Ihnatushchenko, N.; Aboagye, M.O.; Xu, H. Does the nature of airport terminal service activities matter? Processing and non-processing service quality, passenger affective image and satisfaction. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 89, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündoğdu, F.K.; Duleba, S.; Moslem, S.; Aydın, S. Evaluating public transport service quality using picture fuzzy analytic hierarchy process and linear assignment model. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 100, 106920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. The Basic Emotional Impact of Environments. Percept. Mot. Skills 1974, 38, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitner, M.J. Servicescapes: The Impact of Physical Surroundings on Customers and Employees. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The experience economy: Past, present and future. In Handbook on the Experience Economy; Sundbo, J., Sorensen, F., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 1999; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Arnould, E.J.; Price, L.L.; Tierney, P. Communicative Staging of the Wilderness Servicescape. Serv. Ind. J. 1998, 18, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-Y.; Back, R.M.; Bufquin, D.; Shapoval, V. Servicescape, positive affect, satisfaction and behavioral intentions: The moderating role of familiarity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 78, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoglu, B.B.; Bilgihan, A.; Ye, B.H.; Buonincontri, P.; Okumus, F. The impact of servicescape on hedonic value and behavioral intentions: The importance of previous experience. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Kim, W.G.; Ryu, K. The effect of physical environment on passenger delight and satisfaction: Moderating effect of national identity. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Park, J.-W. The effects of the servicescape of airport transfer amenities on the behavioral intentions of transfer passengers: A case study on Incheon International Airport. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 72, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Ding, Y.; Ma, J. The Impact of Airport Physical Environment on Perceived Safety and Domestic Travel Intention of Chinese Passengers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Passenger Satisfaction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakır, M.; Akan, Ş.; Özdemir, E.; Nguyen, P.-H.; Tsai, J.-F.; Pham, H.-A. How to Achieve Passenger Satisfaction in the Airport? Findings from Regression Analysis and Necessary Condition Analysis Approaches through Online Airport Reviews. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, E.A.; Berry, L.L. The Combined Effects of the Physical Environment and Employee Behavior on Customer Perception of Restaurant Service Quality. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2007, 48, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-S.; Park, J.-W.; Choi, Y.-J. Passengers’ Expectations of Airport Service Quality: A Case Study of Jeju International Airport. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Res. 2015, 5, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Blišťanová, M.; Tirpáková, M.; Brůnová, L. Overview of Safety Measures at Selected Airports during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamohammadi, M.; Park, Y.; Choi, J.H.; Kwon, O.K. Exploring the Performance of International Airports in the Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Era: Evidence from Incheon International Airport. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczak, A.; Dembińska, I.; Rozmus, D.; Szopik-Depczyńska, K. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Air Transport Passenger Markets-Implications for Selected EU Airports Based on Time Series Models Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.-H.; Choi, S. A Study on the Perception Change of Passengers on Sustainable Air Transport Following COVID-19 Progress. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, E.; Rizza, U.; Canestrari, F.; Graziani, A.; Virgili, S.; Passerini, G. New Habits of Travellers Deriving from COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey in Ports and Airports of the Adriatic Region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, M. Customer familiarity and its effects on satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Psychol. Mark. 2002, 19, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, J.W.; Hutchinson, J.W. Dimensions of Consumer Expertise. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 13, 411–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avornyo, P.; Fang, J.; Antwi, C.O.; Aboagye, M.O.; Boadi, E.A. Are customers still with us? The influence of optimum stimulation level and IT-specific traits on mobile banking discontinuous usage intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.A.; Dacin, P.A. The Assessment of Alternative Measures of Consumer Expertise. J. Consum. Res. 1996, 23, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampadu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Debrah, E.; Antwi, C.O.; Amankwa, E.; Gyamfi, S.A.; Amoako, R. Online personalized recommended product quality and e-impulse buying: A conditional mediation analysis. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 64, 102789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Yao, Y.; Chang, Y.-C. Research on Customer Behavioral Intention of Hot Spring Resorts Based on SOR Model: The Multiple Mediation Effects of Service Climate and Employee Engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. What Good Are Positive Emotions? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Tasci, A.D. Experienscape: Expanding the concept of servicescape with a multi-stakeholder and multi-disciplinary approach (invited paper for ‘luminaries’ special issue of International Journal of Hospitality Management). Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, L.; Line, N.D. The restaurant social servicescape: Establishing a nomological framework. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. The effect of library indoor environments on occupant satisfaction and performance in Chinese universities using SEMs. Build. Environ. 2019, 150, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Bogicevic, V.; Mattila, A.S. Circular vs. angular servicescape: “Shaping” customer response to a fast service encounter pace. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Kim, M.-S. The effect of the servicescape on customers’ behavioral intentions in an international airport service environment. Serv. Bus. 2012, 6, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, D.; Karagkouni, A. Assortment of Airports’ Sustainability Strategy: A Comprehensiveness Analysis Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Jang, S.S. The Effect of Environmental Perceptions on Behavioral Intentions Through Emotions: The Case of Upscale Restaurants. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2007, 31, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Lee, C.-K.; Lee, S.-K.; Babin, B.J. Festivalscapes and patrons’ emotions, satisfaction, and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Yoon, H.J.; Han, H. Role of Airport Physical Environments in the Satisfaction Generation Process: Mediating the Impact of Traveller Emotion. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 21, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Weber, K. Convention center facilities, attributes and services: The delegates’ perspective. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2005, 10, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K.L.; Blodgett, J.G. Customer response to intangible and tangible service factors. Psychol. Mark. 1999, 16, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K.L.; Blodgett, J.G. The effect of the servicescape on customers’ behavioral intentions in leisure service settings. J. Serv. Mark. 1996, 10, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilnai-Yavetz, I.; Gilboa, S. The Effect of Servicescape Cleanliness on Customer Reactions. Serv. Mark. Q. 2010, 31, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Weaver, D.; Lawton, L. Can stopovers be induced to revisit transit hubs as stayovers? A new perspective on the relationship between air transportation and tourism. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2017, 62, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiredja, D. Assessment of Airport Service Performance: A Passenger-Centred Model. Ph.D. Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Antwi, C.O.; Ntim, S.Y.; Boadi, E.A.; Asante, E.A.; Brobbey, P.; Ren, J. Sustainable cross-border tourism management: COVID-19 avoidance motive on resident hospitality. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boadi, E.A.; He, Z.; Antwi, C.O.; Altab, H.; Bosompem, J.; Hinson, R.E.; Boadi, V.A. Value co-creation and employee service behaviours: The moderating role of trust in employee-hotel relationship. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L.; Wall, E.A.; Carbone, L.P. Service Clues and Customer Assessment of the Service Experience: Lessons from Marketing. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2006, 20, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, C.O.; Fan, C.-J.; Nataliia, I.; Aboagye, M.O.; Xu, H.; Azamela, J.C. Do airport staff helpfulness and communication generate behavioral loyalty in transfer passengers? A conditional mediation analysis. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, A.A.M.; Yahaya, M.F. The relationship between airport image, national identity and passengers delight: A case study of the Malaysian low cost carrier terminal (LCCT). J. Air Transp. Manag. 2013, 31, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, A.A.M.; Maghzi, A. A preliminary study on customer expectations of hotel hospitality: Influences of personal and hotel factors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-C. Effect of servicescape on customer behavioral intentions: Moderating roles of service climate and employee engagement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 53, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, S.A.; Machleit, K.A.; Davis, L.M. Atmospheric qualities of online retailing. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Principles of Marketing Management; Science Research Associates: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Grönroos, C. A Service Quality Model and its Marketing Implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1984, 18, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-W.; Ryu, Y.K. Investigating the Effects of Airport Servicescape on Airport Users’ Behavioral Intentions: A Case Study of Incheon International Airport Terminal 2 (T2). Sustainability 2019, 11, 4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Pratt, G. A description of the affective quality attributed to environments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 38, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotion & Adaptation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Küçükergin, K.G.; Balıkçıoğlu, S. Understanding the Relationships of Servicescape, Value, Image, Pleasure, and Behavioral Intentions Among Hotel Customers. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, S42–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y. Positive emotion bias: Role of emotional content from online customer reviews in purchase decisions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 52, 101891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, N. The Effects of the In-Flight Safety Information Characteristics on the Safety Behavioral Intention of Airline Passengers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, C.; Ren, J.; Owusu-Ansah, W.; Mensah, H.; Aboagye, M. Airport Self-Service Technologies, Passenger Self-Concept, and Behavior: An Attributional View. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Y. An Investigation of the Determinants of Customer Satisfaction. Tour. Anal. 2003, 8, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, V.; Kumar, P.; Tsiros, M. Attribute-Level Performance, Satisfaction, and Behavioral Intentions over Time: A Consumption-System Approach. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, L.S.; Bothner, A.; Spiro, M. How Airports Measure Customer Service Performance: A Synthesis of Airport Practice; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, H.-Y.; Perks, H. Effects of consumer perceptions of brand experience on the web: Brand familiarity, satisfaction and brand trust. J. Consum. Behav. 2005, 4, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.-C.; Lin, H.-C.; Chen, C.-Y. Enhancing Airport Service Quality: A Case Study of Kaohsiung International Airport. J. East. Asia Soc. Transp. Stud. 2013, 10, 2235–2254. [Google Scholar]

- Raju, P.; Lonial, S.C.; Mangold, W.G. Differential Effects of Subjective Knowledge, Objective Knowledge, and Usage Experience on Decision Making: An Exploratory Investigation. J. Consum. Psychol. 1995, 4, 153–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Shu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, Q. Information integration of Hongqiao transportation hub public information platform based on SOA. In Proceedings of the 2010 Seventh International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (FSKD 2010), Yantai, China, 10–12 August 2010; IEEE: Shanghai, China, 2010; pp. 2834–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belle, M.A.; Antwi, C.O.; Ntim, S.Y.; Affum-Osei, E.; Ren, J. Am I Gonna Get a Job? Graduating Students’ Psychological Capital, Coping Styles, and Employment Anxiety. J. Career Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, C.O.; Belle, M.A.; Ntim, S.Y.; Wu, Y.; Affum-Osei, E.; Aboagye, M.O.; Ren, J. COVID-19 Pandemic and International Students’ Mental Health in China: Age, Gender, Chronic Health Condition and Having Infected Relative as Risk Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, F.J. Survey Research Methods, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liou, J.J.; Tang, C.-H.; Yeh, W.-C.; Tsai, C.-Y. A decision rules approach for improvement of airport service quality. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 13723–13730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. An analysis for the competitive strength of Asian major airports. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2003, 9, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Siu, N.Y.-M. Servicescape elements, customer predispositions and service experience: The case of theme park visitors. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.A.; Seo, S. Consumer responses to interactive restaurant self-service technology (IRSST): The role of gadget-loving propensity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.J. Uncovering Dimensionality in the Servicescape: Towards Legibility. Serv. Ind. J. 2007, 27, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, A.; Aiken, L.H.; Heede, K.V.D.; Sermeus, W.; Bruyneel, L.; Lindqvist, R.; Schoonhoven, L.; Stromseng, I.; Busse, R.; Brzostek, T.; et al. A systematic survey instrument translation process for multi-country, comparative health workforce studies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 50, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewil, R.; Appels, L.; Baeyens, J. Energy use of biogas hampered by the presence of siloxanes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2006, 47, 1711–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, P.D. Missing Data Techniques for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehseen, S.; Ramayah, T.; Sajilan, S. Testing and Controlling for Common Method Variance: A Review of Available Methods. J. Manag. Sci. 2017, 4, 142–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.L.; Gillaspy, J.A., Jr.; Purc-Stephenson, R. Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: An overview and some recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, P.A.; Tix, A.P.; Barron, K.E. Testing Moderator and Mediator Effects in Counseling Psychology Research. J. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 51, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Choi, K. Theme restaurants’ servicescape in developing quality of life: The moderating effect of perceived authenticity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 65, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.Y.; Mattila, A.S. Restaurant Servicescape, Service Encounter, and Perceived Congruency on Customers’ Emotions and Satisfaction. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 819–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, J.L. Brand familiarity: Its effects on satisfaction evaluations. J. Serv. Mark. 2008, 22, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-F.; Jang, S.C. An expectancy theory model for hotel employee motivation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Kadan, M. The role of airport service quality in airport and destination choice. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 47, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppens, P.; Stouten, J.; Mesquita, B. Individual differences in emotion components and dynamics: Introduction to the Special Issue. Cogn. Emot. 2009, 23, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, R.; Guerin, S.; McGugan, S. Visitor learning at a heritage attraction: A case study of Discovery as a media product. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, S.E.; Larson, R.J.; Bunce, S.C. Ropressive Coping Style and the Experience and Recall of Emotion: A Naturalistic Study of Daily Affect. J. Pers. 1996, 64, 379–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. An Examination of Need-Satisfaction Models of Job Attitudes. Adm. Sci. Q. 1977, 22, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowds, J.; Aultman-Hall, L.; LaMondia, J.J. Comparing alternative methods of collecting self-assessed overnight long-distance travel frequencies. Travel Behav. Soc. 2020, 19, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Respondents’ Demographics | Descriptive Statistics | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | Mean ± SD | |

| Demographic Profile of Travelers | ||

| Gender | ||

| Men | 186 (48.06%) | |

| Women | 201 (51.94%) | |

| Age category | 34.79 ± 9.11 | |

| <30 years | 92 (23.77%) | |

| 30 to 39 | 139 (35.92%) | |

| ≥40 | 156 (40.31%) | |

| Educational level | ||

| Junior High School | 63 (16.28%) | |

| High/Technical School | 103 (26.61%) | |

| College/Undergraduate/Diploma | 128 (33.07%) | |

| Masters+ | 93 (24.03%) | |

| Travel purpose | ||

| Business | 91 (23.51%) | |

| Education | 112 (28.94%) | |

| Leisure | 184 (47.55%) | |

| Travel Frequency | 3.13 ± 1.21 | |

| Low | 158 (40.83%) | |

| Moderate | 113 (29.20%) | |

| High | 116 (29.97%) | |

| Authors | Items | Descriptive and Normality Statistics | CFA Loadings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Skew, Kurt | γ [CR] | 95% CI (L, U) | ||

| [12,57] | Substantive servicescape (SSoS) | ||||

| FUNC 1. This airport provided comfortable and spacious seating in the waiting areas. | 3.9 ± 0.92 | -1.35, 2.39 | 0.92 [------] | 0.85, 0.95 | |

| FUNC 2. The signs and electronic displays provide information accurately and clearly. | 3.9 ± 0.89 | -1.49, 3.11 | 0.87 [30.83] | 0.82, 0.92 | |

| FUNC 3. The electronics facilities (e.g., television screens, electronic billboards) add excitement to the airport. | 4.03 ± 1.01 | -1.31, 2.39 | 0.88 [30.98] | 0.83, 0.92 | |

| FUNC 4. The airport provided internet/Wi-Fi connectivity. | 3.95 ± 0.93 | -1.44, 2.95 | 0.94 [37.87] | 0.92, 0.96 | |

| FUNC 5. The airport provided international power sockets for charging electronic devices. | 3.99 ± 0.90 | -1.31, 1.64 | 0.90 [32.94] | 0.87, 0.92 | |

| FUNC 6. The elevators, electronic walkways and other services were properly working. | 3.96 ± 0.95 | -1.32, 2.11 | 0.90 [32.83] | 0.83, 0.94 | |

| FA&A 1. The color schemes within the airport were attractive. | 3.85 ± 0.90 | -0.82, 0.51 | 0.91 [-------] | 0.85, 0.93 | |

| FA&A 2. The architecture and decoration of the airport were appealing. | 3.78 ± 1.00 | -1.10, 0.86 | 0.84 [26.10] | 0.77, 0.89 | |

| FA&A 3. The brightness within the airport was welcoming. | 3.44 ± 1.19 | -0.44, -0.75 | 0.51 [12.21] | 0.43, 0.59 | |

| FA&A 4. Temperature within the airport was comfortable. | 3.78 ± 0.96 | -0.83, 0.41 | 0.93 [32.54] | 0.87, 0.95 | |

| FA&A 5. The background music within the airport was appropriate. | 3.77 ± 0.96 | -0.98, 0.83 | 0.77 [22.27] | 0.71, 0.82 | |

| FA&A 6 The aroma within the airport was pleasant. | 3.7 ± 0.98 | -0.89, 0.81 | 0.71 [19.23] | 0.62, 0.78 | |

| LA 1. The airport’s signs clearly directed me to services such as parking, car rentals, terminals, ATM etc. | 3.43 ± 1.07 | -0.63, -0.17 | 0.75 [-------] | 0.69, 0.81 | |

| LA 2. Baggage trolleys were available and conveniently located. | 3.46 ± 1.04 | -0.44, -0.25 | 0.94 [20.94] | 0.91, 0.96 | |

| LA 3. Well-known retail and dining options were available and conveniently located. | 3.62 ± 0.96 | -0.53, -0.09 | 0.73 [16.53] | 0.66, 0.79 | |

| LA 4. The layout was properly managed to avoid passenger crowding and easy movement. | 3.50 ± 1.02 | -0.49, -0.03 | 0.76 [17.26] | 0.70, 0.81 | |

| CLEAN 1. Restrooms and bathrooms in the airport were kept clean. | 3.31 ± 1.11 | -0.51, -0.58 | 0.78 [-------] | 0.72, 0.83 | |

| CLEAN 2. Retail, dining and entertainment areas were kept clean. | 3.59 ± 0.98 | -0.80, 0.54 | 0.87 [19.54] | 0.83, 0.90 | |

| CLEAN 3. Walkways, exits and baggage claim areas were kept clean. | 3.62 ± 1.05 | -0.70, 0.05 | 0.75 [16.94] | 0.69, 0.81 | |

| CLEAN 4. Overall, the airport environment was hygienic. | 3.29 ± 1.14 | -0.46, -0.56 | 0.74 [16.53] | 0.66, 0.80 | |

| [45,50] | Communicative servicescape (CSoS) | ||||

| HC 1. Airport staff were helpful. | 3.43 ± 1.11 | -0.46, -0.48 | 0.87 [-------] | 0.82, 0.91 | |

| HC 2. Airport staff were friendly and courteous. | 3.40 ± 1.13 | -0.30, -0.71 | 0.95 [29.00] | 0.91, 0.97 | |

| HC 3. Airport staff were efficient. | 3.46 ± 1.19 | -0.36, -0.83 | 0.74 [19.81] | 0.67, 0.80 | |

| HC 4. Airport staff communicate in the language I understand. | 3.11 ± 1.16 | -0.09, -0.85 | 0.59 [14.38] | 0.50, 0.67 | |

| LC 1. The airport terminal brings the local culture to me. | 3.61 ± 1.17 | -0.85, -0.11 | 0.91 [-------] | 0.83, 0.95 | |

| LC 2. Chinese “flavors” can be sensed almost everywhere in the terminal. | 3.65 ± 1.13 | -0.95, 0.22 | 0.82 [23.93] | 0.75, 0.89 | |

| LC 3. Chinese designs, arts, and symbols can be seen at the terminal. | 3.74 ± 1.08 | -0.86, 0.22 | 0.72 [19.10] | 0.62, 0.81 | |

| LC 4. Airport staffs’ uniforms are distinctively Chinese. | 3.65 ± 1.14 | -0.88, 0.09 | 0.84 [24.49] | 0.72, 0.90 | |

| LC 5. The airport reflects the national identity of China. | 3.85 ± 1.08 | -0.94, 0.43 | 0.33 [7.23] | 0.22, 0.44 | |

| [5] | Passengers’ positive emotion | ||||

| Pleasure- | |||||

| PPE 1. Happy-unhappy | 5.12 ± 1.54 | -0.88, 0.06 | 0.78 [-------] | 0.78, 0.82 | |

| PPE 2. Pleased-annoyed | 4.30 ± 1.73 | -0.09, -0.86 | 0.79 [18.73] | 0.74, 0.83 | |

| PPE 3. Satisfied-unsatisfied | 5.01 ± 1.56 | -0.67, -0.29 | 0.66 [15.03] | 0.57, 0.73 | |

| PPE 4. Hopeful-despairing | 4.77 ± 1.55 | -0.18, -0.91 | 0.75 [17.66] | 0.69, 0.80 | |

| [67] | Passengers’ Behavioral Loyalty | ||||

| Recommend | |||||

| RC 1. Say positive things about this airport to others. | 3.35 ± 1.11 | -0.33, -0.59 | 0.81 [-------] | 0.75, 0.85 | |

| RC 2. Recommend this airport to someone who seeks my advice. | 3.37 ± 1.08 | -0.25, -0.57 | 0.93 [23.40] | 0.90, 0.96 | |

| RC 3. Encourage friends and relatives to use this airport. | 3.45 ± 1.14 | -0.32, -0.70 | 0.84 [21.09] | 0.78, 0.88 | |

| Repeat Purchase. | |||||

| RP 1. Consider this airport my first choice when traveling. | 4.96 ± 1.33 | -0.61, 0.29 | 0.83 [-------] | 0.76, 0.88 | |

| RP 2. Travel more with this airport in the next few years. | 4.99 ± 1.24 | -0.57, 0.82 | 0.78 [18.13] | 0.72, 0.80 | |

| Pay More | |||||

| PM 1. Continue to travel with this airport even if its prices (charges) increase somewhat. | 4.44 ± 1.48 | 0.02, -0.22 | 0.67 [-------] | 0.57, 0.76 | |

| PM 2. Pay a higher price than other airports’ charges for the benefits you currently receive from this airport. | 4.16 ± 1.55 | 0.05, -0.11 | 0.83 [12.02] | 0.75, 0.90 | |

| [80] | Spend More | ||||

| SP 1. Overall, I like the shopping atmosphere at the airport. | 3.35 ± 1.11 | -0.32, -0.59 | 0.85 [-------] | 0.80, 0.88 | |

| SP 2. I will enjoy shopping in this airport terminal. | 3.37 ± 1.08 | -0.25, -0.57 | 0.89 [24.15] | 0.86, 0.91 | |

| SP 3. I will happily spend extra time browsing. | 3.45 ± 1.14 | -0.32, -0.70 | 0.85 [22.85] | 0.80, 0.90 | |

| SP 4. I will be inclined to spend more money in the shops. | 3.22 ± 1.16 | -0.21, -0.81 | 0.71 [17.66] | 0.65, 0.77 | |

| [67] | Airport Passenger Satisfaction | ||||

| SAT 1. I am satisfied with my decision to use this airport. | 3.87 ± 0.88 | -0.84, 0.77 | 0.76 [-------] | 0.68, 0.82 | |

| SAT 2. If I had to do it all over again, I would use this airport. | 4.00 ± 0.82 | -0.89, 1.33 | 0.84 [18.99] | 0.78, 0.90 | |

| SAT 3. My choice to use this airport was a wise one. | 3.83 ± 1.02 | -0.92, 0.39 | 0.74 [16.48] | 0.79, 0.79 | |

| SAT 4. I think I did the right thing when I decided to use this airport. | 3.86 ± 0.91 | -0.69, 0.39 | 0.70 [15.55] | 0.63, 0.76 | |

| Constructs’ Validity and Reliability | Intern-Construct Correlation Coefficients | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | a | AVE | MSV | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| 1. PM | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.34 | 0.76 | |||||||||||

| 2. PPE | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.58 *** | 0.75 | ||||||||||

| 3. FUNC | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.81 | 0.17 | 0.27 ** | 0.16 * | 0.90 | |||||||||

| 4. FA&A | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.19 * | 0.27 ** | 0.79 | ||||||||

| 5. CLEAN | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 0.29 ** | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.79 | |||||||

| 6. SP | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.68 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.15 * | 0.83 | ||||||

| 7. LC | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.57 | 0.25 | 0.50 *** | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.22 ** | 0.11 * | 0.75 | |||||

| 8. LA | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 0.14 * | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.29 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.800 | ||||

| 9. SAT | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.44 *** | 0.74 *** | 0.24 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.04 | 0.31 ** | 0.35 *** | 0.03 | 0.77 | |||

| 10. HC | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 0.15 * | 0.01 | 0.41 *** | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.27 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.66 *** | 0.21 ** | 0.80 | ||

| 11. RC | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.74 | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.61 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.15 * | 0.40 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.86 | |

| 12. RP | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 0.48 *** | 0.20 ** | 0.10 * | 0.10 * | 0.66 *** | 0.01 | 0.23 ** | 0.21 | 0.16 * | 0.27 ** | 0.04 | 0.77 |

| Covariates, Predictors and Moderator | Standardized Estimates (Critical Ratios) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model1 | Model2 | |||||

| PPE | SAT | RP | RC | PM | SP | |

| Level 1 covariates | ||||||

| Gender b☨ | -0.20 (-6.16) *** | 0.00 (05) NS | 0.02 (0.42) | 0.09 (2.69) ** | 0.01 (0.27) | 0.04 (0.82) |

| Age ✙ | -0.06 (-1.87) NS | 0.00 (.08) NS | 0.01 (.34) | -0.01 (-0.17) | -0.03 (-0.74) | -0.07 (-1.59) |

| Education b☥ | -0.09 (-2.74) ** | -0.04 (-1.09) NS | -0.03 (-0.79) | -0.11 (-3.48) *** | 0.10 (2.30) * | 0.10 (2.28) * |

| Purpose of Travel c☥ | -0.01 (-0.28) NS | -0.12 (-3.24) ** | 0.05 (1.30) | 0.01 (0.46) | 0.03 (0.58) | -0.06 (-1.41) |

| Linear Relations | ||||||

| SSOS | 0.64 (19.97) *** | 0.48 (12.74) *** | ||||

| CSOS | 0.18 (5.59) *** | 0.22 (5.73) *** | ||||

| Passengers’ Positive Emotion | 0.38 (6.71) *** | 0.45 (9.83) *** | 0.12 (1.91) * | 0.26 (4.23) *** | ||

| Passenger Satisfaction | 0.17 (3.03) ** | 0.30 (6.45) *** | 0.22 (3.47) *** | 0.04 (0.57) NS | ||

| Interaction Effects | ||||||

| Travel Frequency (TF) | -0.07 (-2.16) * | -0.06 (-1.45) NS | ||||

| SSOS*TF | -0.05 (-0.39) NS | -0.20 (-1.97) * | ||||

| CSOS*TF | 0.10 (.78) NS | 0.33 (2.22) ** | ||||

| Travel Frequency (TF) | 0.37 (2.91) ** | 0.21 (2.04) ** | 0.031 (2.85) ** | 0.08 (1.51) | ||

| Passengers’ Positive Emotion * TF | -0.13 (-2.05) ** | -0.11 (-1.97) * | -0.19 (-3.09) *** | 0.08 (-1.07) | ||

| Passenger Satisfaction * TF | 0.17 (3.08) *** | -0.09 (-1.78) * | 0.20 (3.13) *** | -0.22 (-3.76) *** | ||

| χ2/df | 2.36 ê/3.95 ë | 3.88 ê/5.82 ë | ||||

| SRMR | 0.04 ê/0.06 ë | 0.06 ê/0.07 ë | ||||

| CFI | 0.98 ê/0.98 ë | 0.95 ê/0.97 ë | ||||

| TLI | 0.96 ê/0.95 ë | 0.92 ê/0.90 ë | ||||

| RMSEA | 0.05ê/0.06ë | 0.06 ê/0.07 ë | ||||

| Paths | β | CR | CI | SE | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSOS-Passengers’ positive emotion | 0.64 | 20.09 | 0.59, 0.69 | 0.01 | <001 |

| CSOS-Passengers’ positive emotion | 0.18 | 5.65 | 0.12, 0.25 | 0.04 | <001 |

| SSOS-Passenger Satisfaction | 0.48 | 12.55 | 0.40, 0.55 | 0.01 | <001 |

| CSOS-Passenger Satisfaction | 0.23 | 5.89 | 0.14, 0.32 | 0.01 | <001 |

| SSOS-Repeat Purchase | 0.53 | 14.13 | 0.42, 0.62 | 0.03 | <001 |

| CSOS-Repeat Purchase | 0.16 | 4.31 | 0.09, 0.23 | 0.03 | <001 |

| SSOS-Recommend | 0.55 | 15.02 | 0.47, 0.61 | 0.02 | <001 |

| CSOS-Recommend | 0.13 | 3.47 | 0.05, 0.20 | 0.03 | <001 |

| SSOS-Pay More | 0.29 | 7.11 | 0.19, 0.39 | 0.05 | <001 |

| CSOS-Pay More | 0.26 | 6.17 | 0.18, 0.33 | 0.05 | <001 |

| SSOS-Spend More | 0.17 | 3.95 | 0.07, 0.27 | 0.04 | <001 |

| CSOS-Spend More | 0.25 | 5.73 | 0.14, 0.34 | 0.04 | <001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antwi, C.O.; Ren, J.; Zhang, W.; Owusu-Ansah, W.; Aboagye, M.O.; Affum-Osei, E.; Agyapong, R.A. “I Am Here to Fly, but Better Get the Environment Right!” Passenger Response to Airport Servicescape. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610114

Antwi CO, Ren J, Zhang W, Owusu-Ansah W, Aboagye MO, Affum-Osei E, Agyapong RA. “I Am Here to Fly, but Better Get the Environment Right!” Passenger Response to Airport Servicescape. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610114

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntwi, Collins Opoku, Jun Ren, Wenyu Zhang, Wilberforce Owusu-Ansah, Michael Osei Aboagye, Emmanuel Affum-Osei, and Richard Adu Agyapong. 2022. "“I Am Here to Fly, but Better Get the Environment Right!” Passenger Response to Airport Servicescape" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610114

APA StyleAntwi, C. O., Ren, J., Zhang, W., Owusu-Ansah, W., Aboagye, M. O., Affum-Osei, E., & Agyapong, R. A. (2022). “I Am Here to Fly, but Better Get the Environment Right!” Passenger Response to Airport Servicescape. Sustainability, 14(16), 10114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610114