Long-Term Development Perspectives in the Slow Crisis of Shrinkage: Strategies of Coping and Exiting

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Development Strategies in Shrinking Cities

2.2. Strategy-Making in Urban Development

3. Methodology

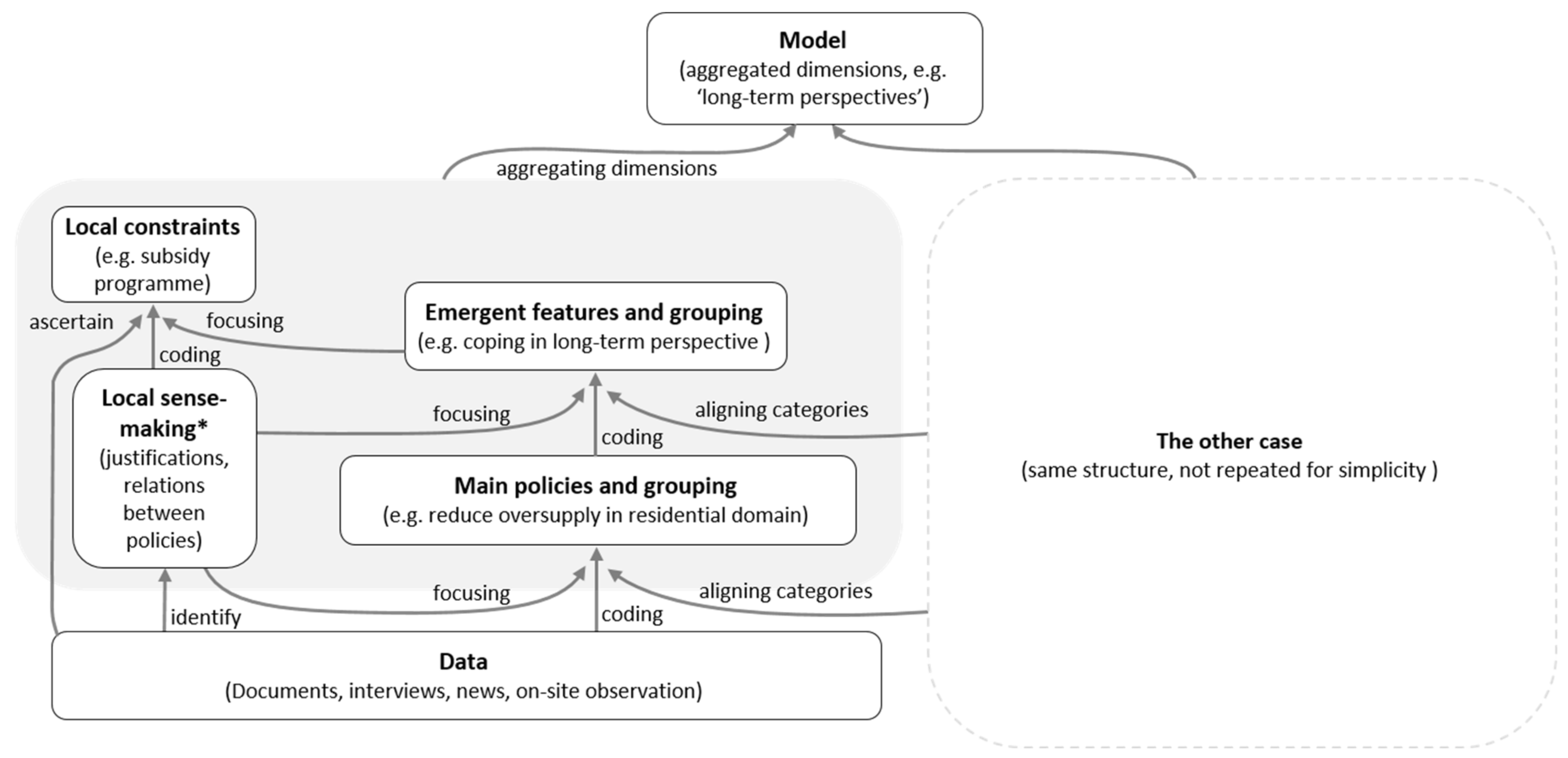

3.1. Objectives and Methods

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Case Study

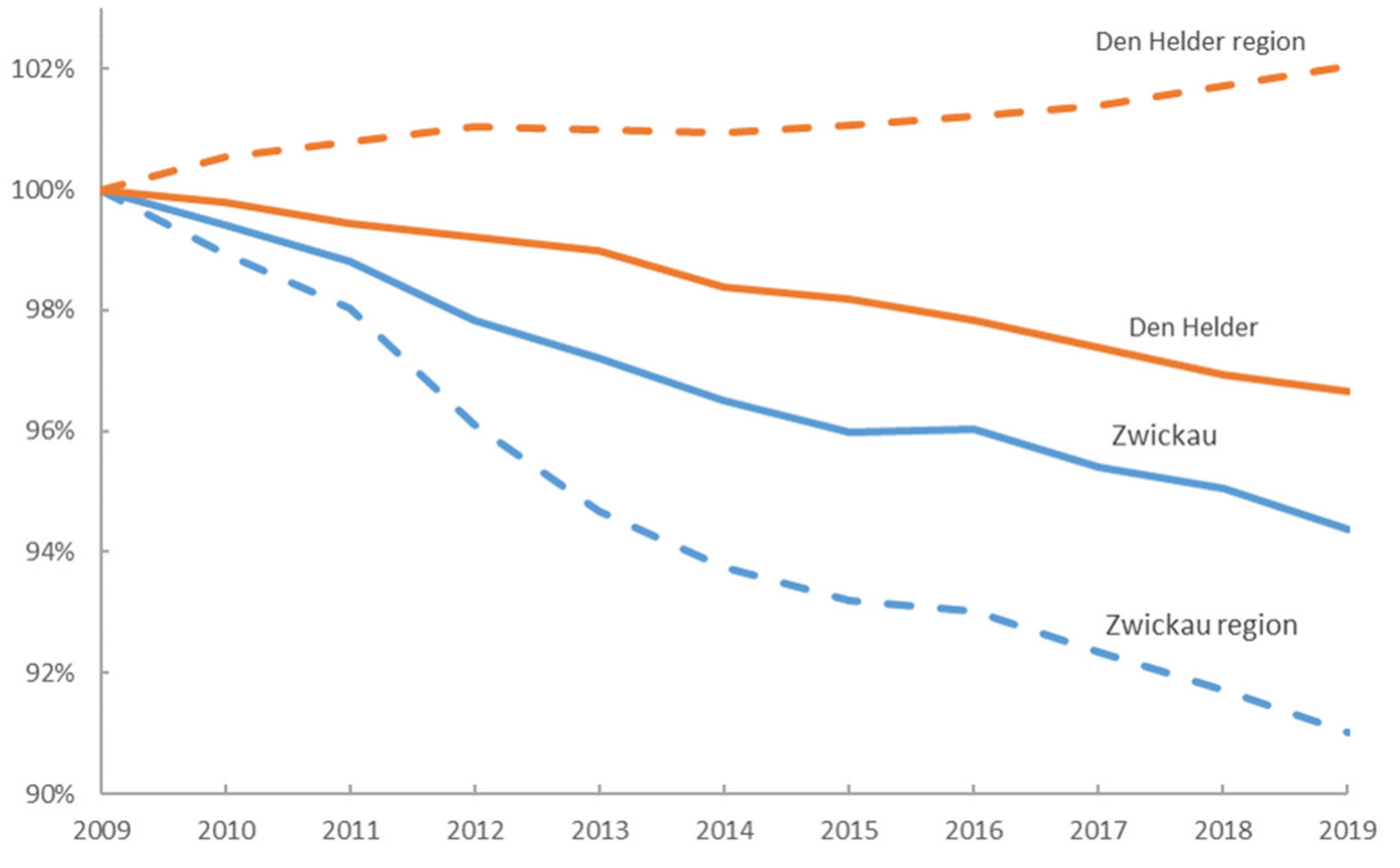

4.1. Case Settings

- Geographic Background

- Experience in tackling shrinkage

- Economic and financial situation

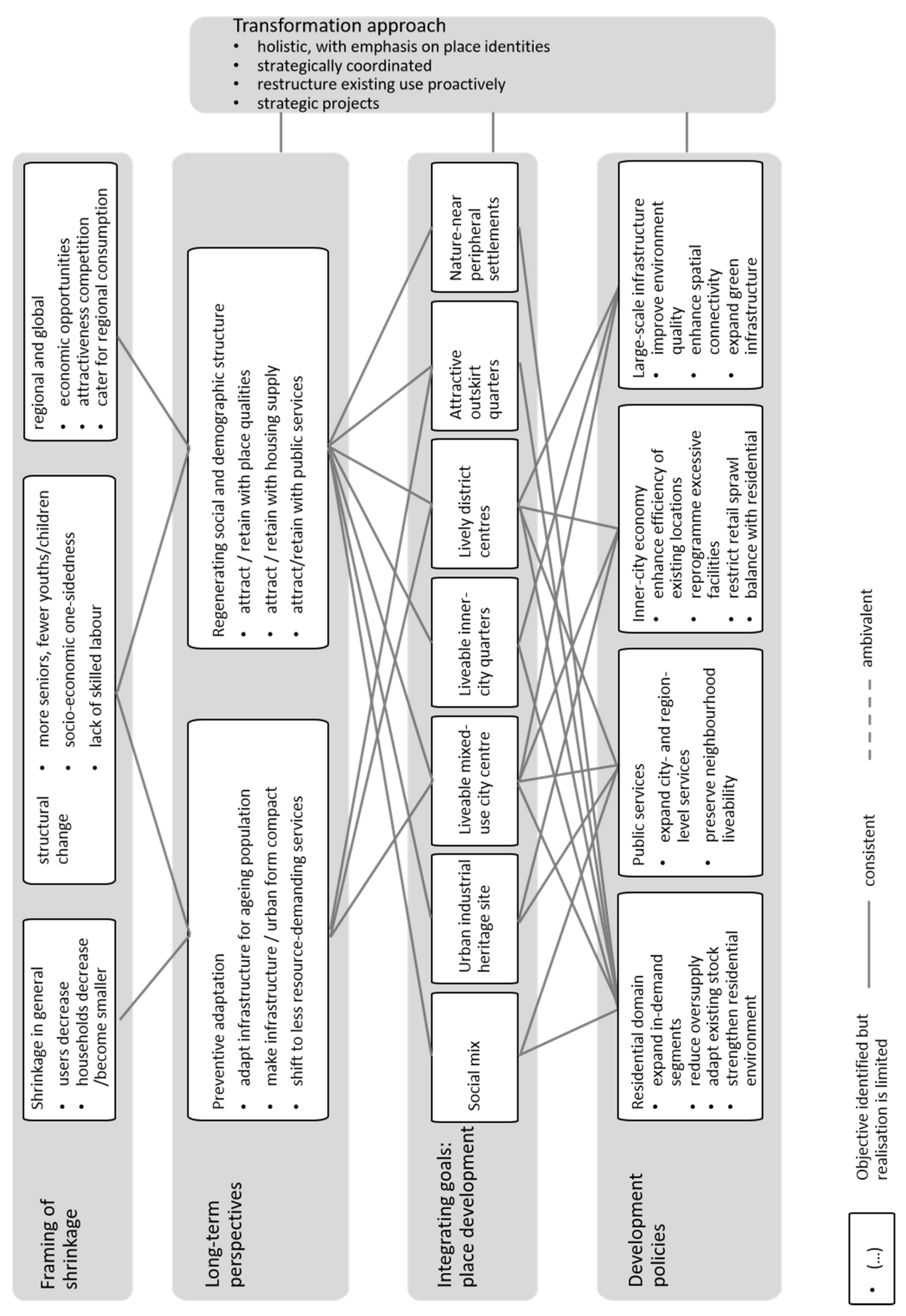

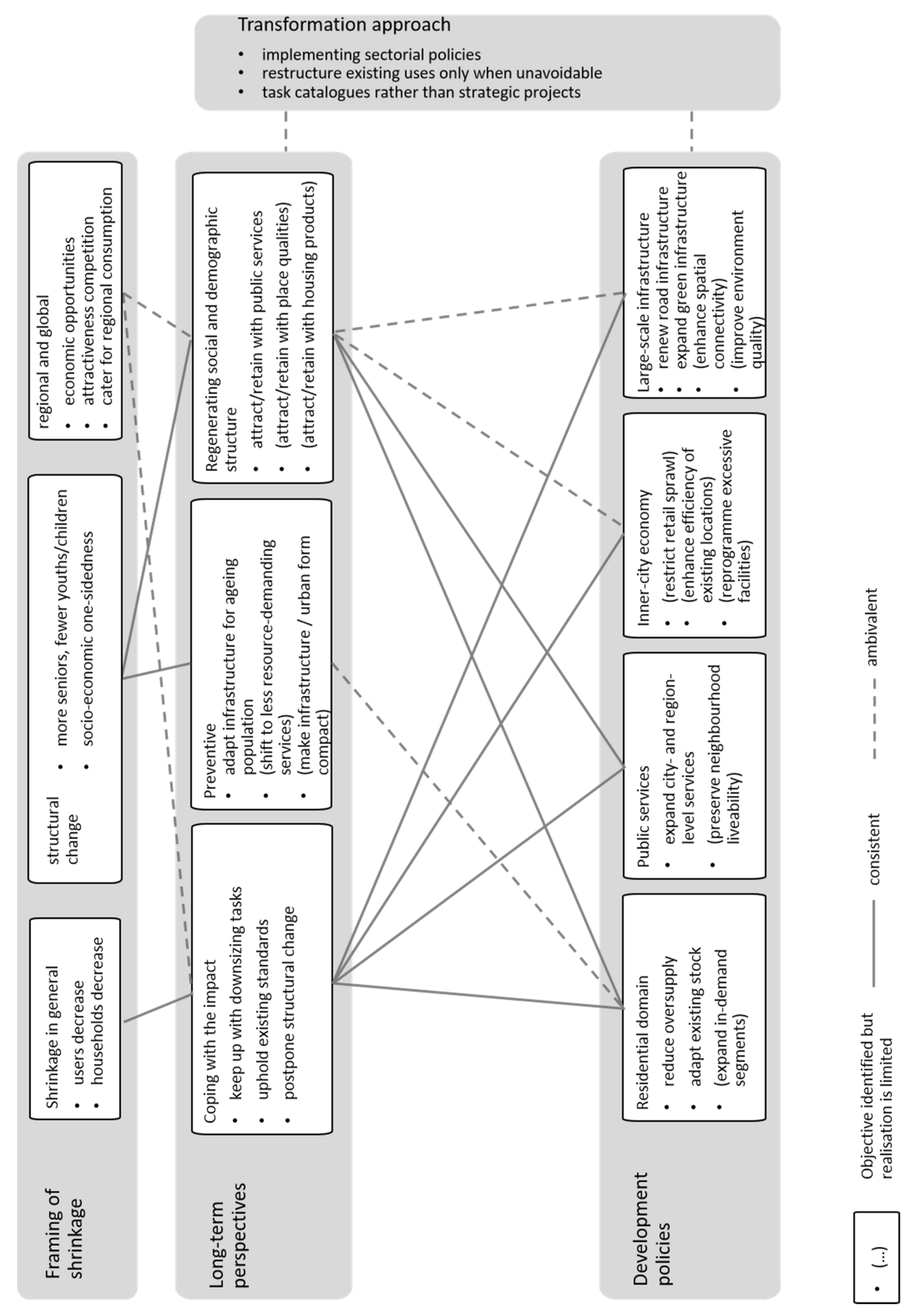

4.2. Development Policies

- Residential domain

- Public services

- Inner-city economy

- Large-scale infrastructure

4.3. Long-Term Perspective and Approach

4.4. Summing-Up: Preliminary Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

- Strategisch Plan Den Helder 2015; Gemeente Den Helder; provided by the municipality

- Strategische Visie 2020; Gemeente Den Helder; https://depot03.archiefweb.eu/archives/archiefweb/20100215134706/http://www.denhelder.nl/index.php?menu_id=400

- Krimp of Niet; Gemeente Den Helder; gemeenteraad.denhelder.nl

- Helder zicht op Zeestad; Gemeente Den Helder; gemeenteraad.denhelder.nl

- Structuurvisie Den Helder 2025; Gemeente Den Helder; denhelder.nl

- Nota Wonen Den Helder; Gemeente Den Helder; denhelder.nl

- Nota Wonen Den Helder 2010–2015; Gemeente Den Helder; denhelder.nl

- Woonvisie Den Helder 2016–2020; Gemeente Den Helder; denhelder.nl

- Prestatieafspraken gemeente Den Helder 2016–2021; Gemeente Den Helder; denhelder.nl

- Regionaal Actie Programma 2017–2020; the Region of Kop van Noord-Holland; noord-holland.nl

- Sociale Structuurvisie: Sociaal en Integraal—Perspectief en Kapstok; Gemeente Den Helder; denhelder.nl

- Uitvoeringsplan Helders perspectief; Gemeente Den Helder; gemeenteraad.denhelder.nl

- Helders Sociaal Beleid: Het sociale verhaal van Den Helder; Gemeente Den Helder; gemeenteraad.denhelder.nl

- Beleidskader sport ‘Den Helder beweegt vooruit’; Gemeente Den Helder; gemeenteraad.denhelder.nl

- Kadernota Detailhandel: Naar kwaliteit en dynamiek; Gemeente Den Helder; https://depot03.archiefweb.eu/archives/archiefweb/20100215134706/http://www.denhelder.nl/index.php?menu_id=429

- Uitwerkingsplan Stadshart; Zeestad; https://zeestad.nl/

- Omgevingsvisie Julianadorp; City of Den Helder; gemeenteraad.denhelder.nl

- Bestemmingsplan Nieuw Den Helder centrum 2013; Gemeente Den Helder; gemeenteraad.denhelder.nl/

- Prognose 2017–2040: Bevolking, huishouden en woningbehoefte; the Province of Noord-Holland; noord-holland.nl

- Landesentwicklungsplan 2013; Sächsisches Staatsministerium des Innern; landesentwicklung.sachsen.de

- Integriertes Stadtentwicklungskonzept (INSEK) Zwickau 2030; Stadt Zwickau; zwickau.de

- Zwickau 2050 Projektbericht; Initiative Zwickau 2050; zwickau2050.de

- Städtebauliches Entwicklungskonzept (SEKo) 2020; Stadt Zwickau; provided by the municipality

- Flächennutzungsplan 2025: Entwurf; Stadt Zwickau; zwickau.de

- Komplexmaßnahme: Innenstadttangente, Querspange Straßenbahn, Bahnhofsvorplatz; Stadt Zwickau; zwickau.de

- Wohnbedarfs- und Wohnbau- Flächenprognose (Wohnkonzept 2018); Stadt Zwickau; zwickau.de

- Wohnungsrückbau in Stadtumbaugebieten: Fortschreibung; Stadt Zwickau; zwickau.de

- Handlungskonzept Wirtschaft Zwickau 2025; Stadt Zwickau; zwickau.de

- Einzelhandels- und Zentrenkonzept Zwickau 2010; Stadt Zwickau; zwickau.de

- Schulentwicklungsplanung Landkreis Zwickau; Landratsamt Landkreis Zwickau; landkreis-zwickau.de

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Code System, Frequency and Relations

| Code System | Coded Segments | Coded Segments % | Code Relations (Inter-Sections) | |

| Case Den Helder | Case Zwickau | |||

| Case setting | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 |

| acceptance of shrinkage | 11 | 11 | 1.4% | 14 |

| regional position | 6 | 3 | 0.6% | 16 |

| experience in tackling shrinkage | 8 | 3 | 0.7% | 14 |

| financial and economic | 3 | 5 | 0.5% | 7 |

| driver of shrinkage | 9 | 4 | 0.8% | 13 |

| Framing shrinkage | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 |

| Shrinkage in general | 1 | 1 | 0.1% | 3 |

| users/consumers decrease | 7 | 7 | 0.9% | 16 |

| households decrease/become smaller | 5 | 7 | 0.7% | 6 |

| structural change | 3 | 0 | 0.2% | 10 |

| more seniors, fewer youths/children | 37 | 29 | 4.1% | 119 |

| socio-economic one-sidedness | 33 | 3 | 2.2% | 50 |

| lack of skilled labour | 28 | 6 | 2.1% | 45 |

| regional and global | 3 | 2 | 0.3% | 4 |

| economic opportunities | 15 | 8 | 1.4% | 14 |

| attractiveness competition | 33 | 6 | 2.4% | 48 |

| cater for regional consumption | 5 | 5 | 0.6% | 25 |

| Transformation approach | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 |

| holistic/ area-oriented approach / identity | 15 | 7 | 1.4% | 30 |

| strategic coordination | 7 | 16 | 1.4% | 46 |

| restructuring existing uses/space | 4 | 8 | 0.7% | 31 |

| strategic projects | 4 | 9 | 0.8% | 17 |

| Long-term perspectives | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 |

| Regenerating | 16 | 9 | 1.6% | 37 |

| attract/retain with place qualities | 24 | 12 | 2.2% | 52 |

| attract/retain with housing products | 8 | 15 | 1.4% | 45 |

| attract/retain with public services | 8 | 12 | 1.2% | 36 |

| Preventive | 0 | 3 | 0.2% | 2 |

| adapt infrastructure for ageing population | 6 | 10 | 1.0% | 41 |

| shift to less resource-demanding services | 16 | 10 | 1.6% | 42 |

| make infrastructure / land use compact | 7 | 5 | 0.7% | 16 |

| Coping | 0 | 2 | 0.1% | 4 |

| keep up with downsizing tasks | 0 | 9 | 0.6% | 15 |

| uphold existing standards | 0 | 16 | 1.0% | 29 |

| postpone structural change | 0 | 31 | 1.9% | 65 |

| Integrating goals | 5 | 8 | 0.8% | 22 |

| Social mix | 10 | 3 | 0.8% | 12 |

| Inner-city industrial heritage | 8 | 0 | 0.5% | 22 |

| Mixed-use city centre | 25 | 18 | 2.7% | 80 |

| Inner-city quarters | 18 | 13 | 1.9% | 55 |

| District centres | 11 | 11 | 1.4% | 31 |

| Outskirt quarters | 4 | 7 | 0.7% | 21 |

| Periphery settlements | 7 | 3 | 0.6% | 15 |

| Development policies | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 |

| Residential domain | 10 | 2 | 0.7% | 18 |

| expand demanded segments | 25 | 20 | 2.8% | 59 |

| owner-occupied | 11 | 7 | 1.1% | 38 |

| medium–high segment | 17 | 20 | 2.3% | 64 |

| affordable quality | 17 | 1 | 1.1% | 36 |

| age-adapted housing | 16 | 11 | 1.7% | 60 |

| innovative forms | 5 | 4 | 0.6% | 10 |

| reduce oversupply | 17 | 35 | 3.2% | 85 |

| adapt existing stock | 9 | 18 | 1.7% | 56 |

| strengthen residential environment | 40 | 22 | 3.9% | 81 |

| Public services | 5 | 4 | 0.6% | 14 |

| expand city- and region-level services | 2 | 1 | 0.2% | 8 |

| healthcare infrastructure | 6 | 4 | 0.6% | 23 |

| admin, cultural facilities | 10 | 14 | 1.5% | 34 |

| high-standard sport facilities | 4 | 19 | 1.4% | 29 |

| preserve neighbourhood liveability | 9 | 0 | 0.6% | 4 |

| service supply | 11 | 11 | 1.4% | 31 |

| schools and daycare | 2 | 18 | 1.2% | 20 |

| amenities | 25 | 6 | 1.9% | 40 |

| co-production | 14 | 7 | 1.3% | 25 |

| Inner-city economy | 14 | 3 | 1.1% | 11 |

| balance with residential quality | 2 | 2 | 0.2% | 5 |

| reprogramme excessive facilities | 8 | 13 | 1.3% | 28 |

| enhance efficiency of existing locations | 9 | 14 | 1.4% | 22 |

| restrict retail sprawl | 8 | 21 | 1.8% | 28 |

| Large-scale infrastructure | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 |

| expand green infrastructure | 7 | 6 | 0.8% | 27 |

| renew road infrastructure | 0 | 17 | 1.1% | 42 |

| improve environment quality | 5 | 25 | 1.9% | 55 |

| enhance spatial connectivity | 1 | 15 | 1.0% | 18 |

| Context, constraints | 0 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 |

| shrinkage dynamics | 5 | 11 | 1.0% | 24 |

| institutional conditions | 3 | 2 | 0.3% | 10 |

| neighbourhood interface | 9 | 3 | 0.7% | 18 |

| superordinate level involvement | 30 | 2 | 2.0% | 38 |

| decision-making and implementation | 25 | 35 | 3.7% | 86 |

| financial instrument | 25 | 19 | 2.7% | 53 |

| material legacies | 5 | 31 | 2.2% | 42 |

| Sum | 821 | 780 | ||

| 1587 | 100.0% | 2412 | ||

References

- Martinez-Fernandez, C.; Weyman, T.; Fol, S.; Audirac, I.; Cunningham-Sabot, E.; Wiechmann, T.; Yahagi, H. Shrinking cities in Australia, Japan, Europe and the USA: From a global process to local policy responses. Prog. Plan. 2016, 105, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswalt, P.; Rieniets, T. Atlas of Shrinking Cities; Hatje Cantz: Ostfildern, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wiechmann, T.; Bontje, M. Responding to Tough Times: Policy and Planning Strategies in Shrinking Cities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, T. ‘Cold spots’ of urban infrastructure: ‘Shrinking’ processes in Eastern Germany and the modern infrastructural ideal. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2008, 32, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bontje, M. Facing the challenge of shrinking cities in East Germany: The case of Leipzig. GeoJournal 2004, 61, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäding, H. Demographic change and local government finance: Trends and expectations. Ger. J. Urban Stud 2004, 43. Available online: http://www.difu.de/node/6061 (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Hackworth, J. The limits to market-based strategies for addressing land abandonment in shrinking American cities. Prog. Plan. 2014, 90, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonaro, G.; Leanza, E.; McCann, P.; Medda, F. Demographic Decline, Population Aging, and Modern Financial Approaches to Urban Policy. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2018, 41, 210–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fol, S. Urban shrinkage and socio-spatial disparities: Are the remedies worse than the disease? Built Environ. 2012, 38, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmeier, K.P.; Bader, S. Demographic decline, segregation and social urban renewal in old industrial metropolitan areas. Ger. J. Urban Stud 2004, 44, 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- González-Leonardo, M.; López-Gay, A.; Demogràfics, C.D. From rural exodus to interurban brain drain: The second wave of depopulation. Ager 2021, 2021, 7–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartt, M. How cities shrink: Complex pathways to population decline. Cities 2018, 75, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slach, O.; Bosák, V.; Krtička, L.; Nováček, A.; Rumpel, P. Urban shrinkage and sustainability: Assessing the nexus between population density, urban structures and urban sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedentop, S.; Fina, S. Urban sprawl beyond Growth: The effect of demographic change on infrastructure costs. Flux 2010, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, S.; Koch, F.; Gawel, E.; Haase, A.; Knapp, S.; Krellenberg, K.; Nivala, J.; Zehnsdorf, A. Introduction. In Urban Transformations: Sustainable Urban Development Through Resource Efficiency, Quality of Life and Resilience; Springer International Publishing: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, H.L.F. Groei en krimp; uitdagingen voor governance en solidariteit. In Land in Samenhang: Krimp en regionale kansengelijkheid; Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, A.; Rink, D.; Grossmann, K.; Bernt, M.; Mykhnenko, V. Conceptualizing urban shrinkage. Environ. Plan. A 2014, 46, 1519–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiechmann, T. Conversion Strategies under Uncertainty in Post-Socialist Shrinking Cities: The Example of Dresden in Eastern Germany. In The Future of Shrinking Cities-Problems, Patterns and Strategies of Urban Transformation; Pallagst, K., Aber, J., Audirac, I., Cunningham-Sabot, E., Fol, S., Martinez-Fernandez, C., Moraes, S., Mulligan, H., Vargas-Hernandez, J., Wiechmann, T., Eds.; Institute of Urban and Regional Development: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pallagst, K.; Fleschurz, R.; Said, S. What drives planning in a shrinking city? Tales from two German and two American cases. Town Plan. Rev. 2017, 88, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz, L.K. What Helps or Hinders the Adoption of ”Good Planning” Principles in Shrinking Cities? A Comparison of Recent Planning Exercises in Sudbury, Ontario and Youngstown, Ohio. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, S.; Pinho, P. Planning for Shrinkage: Paradox or Paradigm. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, S.; Beauregard, R. Must shrinking cities be distressed cities? A historical and conceptual critique. Int. Plan. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, D.L.; Shuster, W.D.; Mayer, A.L.; Garmestani, A.S. Sustainability for shrinking cities. Sustainability 2016, 8, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverda, N.; Hermans, M.; Maurer, N. Towards a culture of degrowth. In Dealing with Urban and Rural Shrinkage: Formal and Informal Strategies; Hospers, G.-J., Syssner, J., Eds.; LIT Verlag Münster: Münster, Germany, 2018; Volume 5, pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, D.E.; Popper, F.J. Small can be beautiful: Coming to terms with decline. Planning 2002, 68, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, J.; Logan, J. Greening the rust belt: A green infrastructure model for right sizing America’s shrinking cities. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2008, 74, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, D.L.; Schwarz, K.; Shuster, W.D.; Berland, A.; Chaffin, B.C.; Garmestani, A.S.; Hopton, M.E. Ecology for the Shrinking City. BioScience 2016, 66, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D. Urban ecology of shrinking cities: An unrecognized opportunity? Nat. Cult. 2008, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A.; Hospers, G.-J.; Pekelsma, S.; Rink, D. Shrinking Areas: Front-Runners in Innovative Citizen Participation; European Urban Knowledge Network: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tomay, K.; Kőszeghy, L.; Török, L.; Šimon, M.; Hoffmann, C.; Peti, M.; Gere, L.; Szabó, B.; Ochojski, A.; Baron, M.; et al. New Innovative Solutions to Adapt Governance and Management of Public Infrastructures to Demographic Change; Office for National Economic Planning: Budapest, Hungary, 2014; Available online: https://www.soc.cas.cz/sites/default/files/publikace/adapt2dc_wp6_e-book_20140517.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Schlappa, H. Co-producing the cities of tomorrow: Fostering collaborative action to tackle decline in Europe’s shrinking cities. Eur. Urban Reg. 2017, 24, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, B. The role of the social economy in the Shrinking city. In Future Directions for the European Shrinking City; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mallach, A. What we talk about when we talk about shrinking cities: The ambiguity of discourse and policy response in the United States. Cities 2017, 69, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreichauf, R. Being on the Losing Side of Global Urban Development? The Limits to Managing Urban Decline. In Proceedings of the European Regional Science Association; 2014. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:wiw:wiwrsa:ersa14p94 (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Hackworth, J. Urbanization, planning and the possibility of being post-growth. In The Routledge Handbook on Spaces of Urban Politics; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Dubeaux, S.; Cunningham-Sabot, E. Maximizing the potential of vacant spaces within shrinking cities, a German approach. Cities 2018, 75, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, B.B. Van leefbaarheid naar toekomstkracht: Inspiratie voor een nieuw krimpbeleid. In Land in Samenhang: Krimp en regionale kansengelijkheid; Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, L. Critiques of the Shrinking Cities Literature from an Urban Political Economy Framework. J. Plan. Lit. 2020, 35, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz, L.K. Going for growth and managing decline: The complex mix of planning strategies in Broken Hill, NSW, Australia. Town Plan. Rev. 2017, 88, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenfeucht, R.; Nelson, M. Just revitalization in shrinking and shrunken cities? Observations on gentrification from New Orleans and Cincinnati. J. Urban Aff. 2020, 42, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tighe, J.R.; Ganning, J.P. Do Shrinking Cities Allow Redevelopment Without Displacement? An Analysis of Affordability Based on Housing and Transportation Costs for Redeveloping, Declining, and Stable Neighborhoods. Housing Pol. Debate 2016, 26, 785–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L. Strategic (spatial) planning reexamined. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2004, 31, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.E. Consensus building: Clarifications for the critics. Plan. Theory 2004, 3, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. In search of the “strategic” in spatial strategy making. Plann. Theory Prac. 2009, 10, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, G.; Walter, S.; Thomas, S. Die Planungsstrategie der IBA Emscher Park. Eine Annäherung. RaumPlanung 1993, 61, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wiechmann, T. Planung und Adaption: Strategieentwicklung in Regionen, Organisationen und Netzwerken; Rohn: Dortmund, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Großmann, K.; Bontje, M.; Haase, A.; Mykhnenko, V. Shrinking cities: Notes for the further research agenda. Cities 2013, 35, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, M.; Haase, A.; Großmann, K.; Cocks, M.; Couch, C.; Cortese, C.; Krzysztofik, R. How does(n’t) Urban Shrinkage get onto the Agenda? Experiences from Leipzig, Liverpool, Genoa and Bytom. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1749–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döringer, S.; Uchiyama, Y.; Penker, M.; Kohsaka, R. A meta-analysis of shrinking cities in Europe and Japan. Towards an integrative research agenda. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 1693–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, C.; Sykes, O.; Börstinghaus, W. Thirty years of urban regeneration in Britain, Germany and France: The importance of context and path dependency. Prog. Plan. 2011, 75, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebmann, H.; Kuder, T. Pathways and strategies of urban regeneration—deindustrialized cities in eastern Germany. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 1155–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H.M. Slow growth and decline in Greater Sudbury: Challenges, opportunities, and foundations for a new planning agenda. Can. J. Urban Res. 2009, 18, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R. Strategies for sustainability in shrinking cities: Frames, rationales and goals for a development path change. Nordia Geographical Publications 2021, 49, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiechmann, T. Errors expected—aligning urban strategy with demographic uncertainty in shrinking cities. Int. Plan. Stud. 2008, 13, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartt, M.; Warkentin, J. The development and revitalisation of shrinking cities: A twin city comparison. Town Plan. Rev. 2017, 88, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoop, B. Nothing but Growth for Shrinking Cities? Urban Planning and its Influencing Factors in Poland. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Degrowth for Ecological Sustainability and Social Equity, Leipzig, Germany, 2–6 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, F.; Kabisch, N. The Relation of Diverging Urban Growth Processes and Demographic Change along an Urban–Rural Gradient. Popul. Space Place 2012, 18, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kübler, A.; Strauß, C.; Warner, B. Regional land use management under shrinkage tendencies in the region Halle-Leipzig. In Parallel Patterns of Shrinking Cities and Urban Growth: Spatial Planning for Sustainable Development of City Regions and Rural Areas; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2012; pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Nuissl, H.; Rink, D. The ‘production’of urban sprawl in eastern Germany as a phenomenon of post-socialist transformation. Cities 2005, 22, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, K.; Gruezmacher, M.; Deacon, L. Land use tools for tempering boom and bust: Strategy and capacity building in governance. Land Use Policy 2020, 93, 103994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, L.O. Urban Triage, City Systems, and the Remnants of Community: Some “Sticky” Complications in the Greening of Detroit. J. Urban Hist. 2015, 41, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackworth, J. Rightsizing as spatial austerity in the American Rust Belt. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2015, 47, 766–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, L. The Shrinking City as a Growth Machine: Detroit’s Reinvention of Growth through Triage, Foundation Work and Talent Attraction. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2020, 44, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospers, G.-J. Policy responses to urban shrinkage: From growth thinking to civic engagement. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1507–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.B.; Németh, J. The bounds of smart decline: A foundational theory for planning shrinking cities. Housing Pol. Debate 2011, 21, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürkner, H.-J.; Kuder, T.; Kühn, M. Regenerierung schrumpfender Städte. Theoretische Zugänge und Forschungsperspektiven; Working Paper, No. 28; Leibniz-Institut für Regionalentwicklung und Strukturplanung (IRS): Erkner, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bernt, M. Partnerships for demolition: The governance of urban renewal in East Germany’s shrinking cities. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 754–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, L.; Haase, A.; Heiland, S. Gentrification through Green Regeneration? Analyzing the Interaction between Inner-City Green Space Development and Neighborhood Change in the Context of Regrowth: The Case of Lene-Voigt-Park in Leipzig, Eastern Germany. Land 2020, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miot, Y. Residential Attractiveness as a Public Policy Goal for Declining Industrial Cities: Housing Renewal Strategies in Mulhouse, Roubaix and Saint-Etienne (France). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, M. Re-imaging the City Centre for the Middle Classes: Regeneration, Gentrification and Symbolic Policies in ‘Loser Cities’. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 770–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospers, G.-J. Place marketing in shrinking Europe: Some geographical notes. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2011, 102, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slach, O.; Nováček, A.; Bosák, V.; Krtička, L. Mega-retail-led regeneration in the shrinking city: Panacea or placebo? Cities 2020, 104, 102799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojnovic, I. Urban sustainability: Research, politics, policy and practice. Cities 2014, 41, S30–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, C. Towards a regenerative paradigm for the built environment. Build. Res. Inf. 2012, 40, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugmann, J. Overview. In Urban Sustainability: A Global Perspective; Vojnovic, I., Ed.; Michigan State University Press: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2012; Volume 9781609173470, pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bernt, M.; Cocks, M.; Couch, C.; Grossmann, K.; Haase, A.; Rink, D. Shrink Smart: Policy Response, Governance and Future Directions. Research Brief; UFZ: Leipzig, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wiechmann, T.; Pallagst, K. Urban shrinkage in Germany and the USA: A Comparison of Transformation Patterns and Local Strategies. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauß, C. The importance of strategic spatial goals for the planning process under shrinkage tendencies. In Parallel Patterns of Shrinking Cities and Urban Growth: Spatial Planning for Sustainable Development of City Regions and Rural Areas; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2012; pp. 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Albrechts, L.; Healey, P.; Kunzmann, K.R. Strategic spatial planning and regional governance in Europe. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2003, 69, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. The treatment of space and place in the new strategic spatial planning in Europe. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 28, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L. Some ontological and epistemological challenges. In Situated Practices of Strategic Planning; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Salet, W.; Faludi, A. Three approaches to strategic spatial planning. In The Revival of Strategic Spatial Planning: Proceedings of the Colloquium, Amsterdam, 25–26 February 1999; Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 155, p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan International Higher Education: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin, D.L. Strategies for cities and counties: A strategic planning guide; Public Technology: Washington, DC, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Urban Complexity and Spatial Strategies: Towards a Relational Planning for Our Times, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kunzmann, K. Strategic planning: A chance for spatial innovation and creativity. DISP 2013, 49, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L.; Barbanente, A.; Monno, V. Practicing transformative planning: The territory-landscape plan as a catalyst for change. City Territ. Archit. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastop, H.; Faludi, A. Evaluation of Strategic Plans: The Performance Principle. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1997, 24, 815–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, J.L.; Wildavsky, A. Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington Are Dashed in Oakland; Or, Why It’s Amazing that Federal Programs Work at All, This Being a Saga of the Economic Development Administration as Told by Two Sympathetic Observers Who Seek to Build Morals on a Foundation; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H.; Ahlstrand, B.; Lampel, J. Strategy Safari: A Guided Tour through the Wilds of Strategic Mangament; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom, C.E. The science of” muddling through”. Public Admin. Rev. 1959, 19, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, A. Mixed-scanning: A” third” approach to decision-making. Public Admin. Rev. 1967, 27, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, R.; Karnøe, P. Bricolage versus breakthrough: Distributed and embedded agency in technology entrepreneurship. Res. Pol. 2003, 32, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L. Ingredients for a more radical strategic spatial planning. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2015, 42, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gerring, J. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices; Cambridge university press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Audirac, I. Shrinking cities: An unfit term for American urban policy? Cities 2018, 75, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, D.; Couch, C.; Haase, A.; Krzysztofik, R.; Nadolu, B.; Rumpel, P. The governance of urban shrinkage in cities of post-socialist Europe: Policies, strategies and actors. Urban Research and Practice 2014, 7, 258–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, D.; Haase, A.; Grossmann, K.; Couch, C.; Cocks, M. From long-term shrinkage to re-growth? the urban development trajectories of Liverpool and Leipzig. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domhardt, H.-J.; Troeger-Weiß, G. Germany’s shrinkage on a small town scale. In The Future of Shrinking Cities: Problems, Patterns and Strategies of Urban Transformation in a Global Context; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Grounded theory and sensitizing concepts. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haig, B.D.; Evers, C.W. Realist Inquiry in Social Science; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sector Onderzoek & informatie. Prognose 2017–2040: Bevolking, Huishouden en Woningbehoefte; Provincie Noord-Holland: Germany, 2017; Available online: https://www.noord-holland.nl/Onderwerpen/Ruimtelijke_inrichting/Demografie/Beleidsdocumenten/Bevolkingsprognose_Noord_Holland_2017_2040.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Timourou. Wohnbedarfs- und Wohnbau- Flächenprognose der Stadt Zwickau; Stadt Zwickau: Zwickau, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Statistisches Landesamt des Freistaates Sachsen. 7. Regionalisierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung für den Freistaat Sachsen 2019 bis 2035, Gemeinde Zwickau, Stadt; Statistisches Landesamt des Freistaates Sachsen: Kamenz, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gemeente Den Helder. Bevolkingsontwikkeling 1960–2017. Available online: https://archief09.archiefweb.eu/archives/archiefweb/20180710165008/http://www.denhelder.nl/data/publicatie-website/bevolking/Bevolkingsontwikkeling%201960-2017.pdf?_dc=1492089430225&_dc=1492089430241 (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Stadt Zwickau. Städtebauliches Entwicklungskonzept (SEKo) Zwickau 2020; Stadt Zwickau: Zwickau, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stadt Zwickau. Zahlen und Fakten 2009–2019; Stadt Zwickau: Zwickau, Germany, 2009–2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gemeente Den Helder. Woonvisie Den Helder 2016–2020: In Den Helder kan meer! Gemeente Den Helder: Den Helder, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsmann Stiftung. Wegweiser Kommune Open Data. Available online: https://www.wegweiser-kommune.de/daten (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- CBS. Regionale kerncijfers Nederland. Available online: https://opendata.cbs.nl (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Statistisches Landesamt Sachsen. Regionaldaten Gemeindestatistik Sachsen. Available online: https://statistik.sachsen.de/Gemeindetabelle/ (accessed on 26 July 2021).

- Den Helder gaat Falgabuurt na overlast slopen. De Volkskrant, 6 November 1998.

- Deetman, W.; Mans, J. Krimp of Niet: Advies Betreffende Demografische Ontwikkeling Den Helder; Gemeente Den Helder: Den Helder, The Netherlands, 2010; Available online: https://gemeenteraad.denhelder.nl/Documenten/onbekend/Rapport-Deetman-Mans-Den-Helder.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- BMWSB. Zwickau-Eckersbach. Available online: https://www.staedtebaufoerderung.info/DE/ProgrammeVor2020/Stadtumbau/Praxis/Praxisbeispiele/Zwickau/Zwickau.html (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Gemeente Den Helder. Programmarekening 2015–2019. Available online: https://gemeenteraad.denhelder.nl (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Provincie Noord-Holland. Uitvoeringsregeling Regionale Afspraken Nieuwe Stedelijke Ontwikkelingen. 2017. Available online: https://www.noord-holland.nl/Onderwerpen/Ruimtelijke_inrichting/Omgevingsvisie_en_PRV/Beleidsdocumenten/Uitvoeringsregeling_regionale_afspraken_nieuwe_stedelijke_ontwikkelingen_2017 (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Gemeente Den Helder. Prestatieafspraken Gemeente Den Helder; Gemeente Den Helder: Den Helder, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- CBS. Landelijke Monitor Leegstand, 2015–2019. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/-/media/_excel/2019/48/landelijke-leegstandsmonitor-2015-2019.zip (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Gemeente Den Helder. Structuurvisie Den Helder 2025; Gemeente Den Helder: Den Helder, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stadt Zwickau. Integriertes Stadtentwicklungskonzept (INSEK): Zwickau 2030; Stadt Zwickau: Zwickau, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gemeente Den Helder. Kadernota Detailhandel: Naar Kwaliteit en Dynamiek; Gemeente Den Helder: Den Helder, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich, K.; Hahn, C. Lebenswer Einnenstadt? Ein Handlungskonzept zur Revitalisierung von Leerstand und Brachflächen in Innerstädtischen Gebieten der Stadt Zwickau. Master’s Thesis, Brandenburgische Technische Universität Cottbus, Cottbus, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- GMA. Einzelhandels- und Zentrenkonzept Zwickau 2010; Stadt Zwickau: Zwickau, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stadt Zwickau. 93 Prozent der Bürger sind zufrieden damit, in Zwickau zu leben. Available online: https://www.zwickau.de/de/aktuelles/pressemitteilungen/2016/04/156.php (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Friedrich, G. Ausschuss schickt Mammutprojekt in die nächste Planungsrunde. Radio Zwickau, 6 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Boverhoff, E.; Rus, T. Den Helder: Kantelen naar de gebiedsgerichte aanpak. Stadswerk Magazine, 21 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zeestad. Uitwerkingsplan Stadshart; 2008. Available online: https://zeestad.nl/ontwikkeling/uitwerkingsplan-stadshart (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Rekenkamercommissie Den Helder. Helder zicht op Zeestad; Gemeente Den Helder: Den Helder, The Netherlands, 2012; Available online: https://gemeenteraad.denhelder.nl/Documenten/onbekend/Integraal-rapport-rkc-Helder-zicht-op-Zeestad.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- Rink, D.; Kabisch, S. Introduction: The ecology of shrinkage. Nat. Cult. 2009, 4, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A.; Bernt, M.; Großmann, K.; Mykhnenko, V.; Rink, D. Varieties of shrinkage in European cities. Eur. Urban Reg. 2016, 23, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, M. The Limits of Shrinkage: Conceptual Pitfalls and Alternatives in the Discussion of Urban Population Loss. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2016, 40, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A.K. Shrinking cities: Fuzzy concept or useful framework? Berkeley Plan. J. 2013, 26, 107–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.; Wiechmann, T. Urban growth and decline: Europe’s shrinking cities in a comparative perspective 1990–2010. Eur. Urban Reg. 2018, 25, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelsmann Stiftung. Demografietypisierung 2020. Available online: https://www.wegweiser-kommune.de/demografietypen (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Hutter, G.; Wiechmann, T. Time, Temporality, and Planning—Comments on the State of Art in Strategic Spatial Planning Research. Plan. Theory Pract. 2022, 23, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viganò, P. Elements for a theory of the city as renewable resource. In Recycling City, Lifecycles, Embodied Energy, Inclusion; Giavedoni: Pordenone, Italy, 2012; pp. 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J.; Kębłowski, W. Spatialising degrowth, degrowing urban planning. Local Environ. 2022, 27, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Den Helder | Zwickau | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 55,600; peak 64,000 (1985) [108] −0.33% p.a. in the last decade Households: 26,770, +0.11% p.a. | 89,540; peak: 138,880 (1950) [109] −0.58% p.a. in the last decade Households [110]: 49,329, +0.19% p.a., but in the last five years −0.22% p.a. |

| Regional population | Population 375,659, +0.2 % p.a. Households 165,902, +0.6 % p.a. | Population 317,531, −0.9% p.a. Households 166,300, −0.77% p.a. |

| Demographical structure | Structural changes: Over 65 from 15.8% to 23% 25–45 from 26.1% to 22.5% Under 25 from 28% to 25% Ten-year natural demographic balance: −235; 12% of shrinkage | Structural changes: Over 65 from 25.8% to 28.8% 25–45 from 24.4% to 22.7% Under 25 from 20.5% to 19.7% Ten-year natural demographic balance: −5500; 103.4% of shrinkage |

| Economy | Local jobs: 63 % in Branches O–U 2, incl. c.a. 36.7% in the navy [111] Regional (average of last five years): GDP per capita €29,070; spendable income of households per capita €18,800 3 | Local jobs: 29% in Branches O–U, 33% in Branch B–F Regional (average of last five years): GDP per capita €30,000 [112]; spendable income of households per capita €20,300 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, R. Long-Term Development Perspectives in the Slow Crisis of Shrinkage: Strategies of Coping and Exiting. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610112

Liu R. Long-Term Development Perspectives in the Slow Crisis of Shrinkage: Strategies of Coping and Exiting. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610112

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ruiying. 2022. "Long-Term Development Perspectives in the Slow Crisis of Shrinkage: Strategies of Coping and Exiting" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610112

APA StyleLiu, R. (2022). Long-Term Development Perspectives in the Slow Crisis of Shrinkage: Strategies of Coping and Exiting. Sustainability, 14(16), 10112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610112