2.1. Conceptualization of Nature as a Value

People’s values are diverse. By exploring their values, people describe and justify the importance of their needs, actions, and life priorities. According to scholars, the latter depend on people’s characteristics, life experience and life events, and motivation for actions. As suggested by Schwartz et al. [

16,

17], values may reflect major social change in societies and across nations. An analysis of the scientific literature has revealed that although caring for nature is a cultivated subject influenced by external factors, it is also determined by various personal characteristics: social, demographic, and economic. Understanding the value of nature from the local residents’ perspective enables identifying the socio-economic groups that are the most interested in nature and its preservation or, on the contrary, the target groups that might need to be educated in order to raise their awareness for the purpose of the preservation of nature as a value.

The abundance of scientific literature dealing with environmental issues, environmental protection, and climate change emphasizes that people are not only a part of nature, but they themselves are heavily influenced by the changes taking place in nature. Therefore, as a result of people’s presence in nature and various economic and social activities, many countries have already realized that it is necessary to make appropriate contributions for the purpose of the conservation of nature [

7,

18,

19]. On the other hand, many scientists acknowledge that people’s activities, behavior, and motives depend on their values in relation to nature, e.g., the extent of our concern, care for, or sense of responsibility for the conservation and preservation of nature [

4,

20,

21]. These questions have naturally become part of an international survey in Europe—the European Social Survey [

22]. The survey measures the attitudes, beliefs, and behavior patterns of diverse populations on various topics, including issues related to values of care for nature.

Concerns about biodiversity and protected areas also signal the growing environmental awareness. According to the Nature Awareness Study 2019 [

23], the majority of inhabitants in Germany agreed that protected areas were important for the preservation of nature for future generations (93%). The Nature Awareness Study 2017 [

24] revealed that the population of Germany placed great importance on the sustainable exploitation of the seas, with major focus on the risks to biodiversity due to waste and pollutants.

In addition, Farjon et al. [

20] have noted that people’s perception of the value of nature partly depends on their beliefs and motives, as well as changes thereof. In addition, the perception of nature as a value is influenced by how people discuss nature-related issues and treat nature, as prior experiences in relation to nature are fairly important, starting with childhood. Furthermore, many studies justify multiple ways in which people may view and value nature, thereby creating a diverse image of nature. The engagement of people with nature (participation in activities involving the natural environment) contributes to the strengthening of the attachment to nature [

25].

In the research by Brito et al. [

7], almost all of the respondents stated that they had a positive opinion about the protected areas of the analyzed municipality, and the essential aspect for caring for nature was related to decision making and public policy making.

Díaz et al. [

6] have pointed out that nature becomes a value for people when it contributes to their lives. This can be viewed from the material approach (defined as substances, objects, and other natural elements), regulating approach (functional and structural aspects that affect people’s lives indirectly), and non-material approach (the effects of nature on the subjective and psychological aspects that influence both the individual and collective quality of life).

According to the research by Anderson, Krettenauer [

9], emotional connectedness is one of the strongest predictors of pro-environmental behavior, as suggested by the analysis conducted by the authors. Moreover, their research has shown that adults displayed significantly higher levels of emotional connectedness to nature and pro-environmental behavior in comparison to adolescents and that females show higher levels of both emotional connectedness to nature and pro-environmental behavior compared to males, and that urban and rural participants significantly differed in their levels of pro-environmental behavior.

Wang et al. [

21] examined the relationships between adult interest in scientific issues and relatedness to nature. The authors described nature relatedness (or nature connectedness) as a psychological construct that can reflect an individual’s perception of his or her relation to the natural world. It is also clear that nature relatedness is associated with ecological thinking. Ecological thinking defines how humans and the environment are related. It originates from factors such as values, beliefs, and attitudes that lead the individuals to engage in specific behaviors and actions [

5,

6,

11]. In fact, nature relatedness appears as an individual interest and as a reflection of positions (positive/negative) regarding the natural environment and environmental issues. If citizens’ connection to and experiences in nature encourage them to be and act in nature, this gives rise to a positive perception of nature [

26]. Otherwise, in the case of negative experiences associated with being in nature, a negative attitude towards nature develops.

The analyzed literature disclosed that, from the perspective of society, the care for and preservation of nature is important for the following: public policy decisions concerning nature and its measures; economic decision making related to investments and economic activity; promotion of an inclusive society and securing better wellbeing for all social groups.

2.2. Determinants of Perception of the Natural Environment as a Value

There are several studies that demonstrate gender and education being among the key determinants of an environmental attitude. Women and more educated individuals have higher level of environmental awareness than men and people with a low level of education [

27]. Their research led to a conclusion that people with a higher education and women are more likely to pay more for environmentally friendly products. In their studies, authors Schultz et al. [

10] and DeVille et al. [

28] found that environmental attitudes are largely understood individually and constructed socially as an individual’s beliefs affect behavioral intentions regarding nature and environmentally related activities or issues. Raymond et al. [

29] put emphasis on place attachment, where nature as an attribute of a particular area stresses the connection between the individual, community, and nature.

According to a survey in the recently published Eurobarometer report “Future of Europe” [

19] evaluating different values, major global challenges, and priorities, the respondents claimed that the environment and climate change (39%) should be prioritized, four in ten respondents (38%) said that the European Union (EU) best embodied respect for nature and the environment, and at least eight in ten mentioned various environmental objectives that were very or “fairly” important to them personally. According to the same report, at least one in five respondents in Poland (23%) and only 5 percent of the respondents in Lithuania pointed out the respect for nature and claimed that the environment was best embodied by other countries rather than in their native country. More diverse attitudes were observed in relation to the respect for nature and the environment compared to other values: men, respondents in the age group 15–39, respondents who completed education at the age of 20 or more, the self-employed, managers, students, and the respondents who experience the least financial difficulties are most likely to consider that respect for nature and the environment is best embodied by the EU. For all other groups, respondents are most likely to say that this value is best embodied by the EU and others. For example, 41% of men claimed that respect for nature and the environment was best embodied by the EU, while 38% believed it was best embodied by the EU and other countries. According to 35% of the women, it was best embodied by the EU and 42%—the EU and other countries.

According to the findings by Gifford and Nilsson [

30] and DeVille et al. [

28], time spent in nature is associated with better pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. The authors have emphasized that time spent in nature is reflected in the values ascribed to nature and nature connectedness, and this depends on personal and social factors (e.g., age, gender, socio-economic status, geographic location, urban–rural differences, and socio-economic status). The need for research at the population level that integrates mentioned factors increases when it is aimed at gaining a better understanding of the society, its attitudes, intensities, and envisaging political and educational measures to strengthen environmental awareness [

29,

31]. The authors’ idea is that the associations between childhood, nature exposure, and time spent in nature have an impact on these people’s future and attitude to nature and its preservation. Several research studies have demonstrated that aging has a positive effect on the perception of nature [

18,

28]. Starting with childhood, these demographic contexts predict environmental attitudes and behaviors in adulthood. The authors have also noted that time spent in nature increases the importance of nature as a value. This finding is supported by many researchers, as nature has a mostly positive impact on human consciousness, health, and overall wellbeing, and this value can be nurtured and developed throughout life.

The peculiarities of the living place are also associated with nature, regardless of where one lives. A sense of living place is an important factor in nature-related population studies; in particular, when the rural–urban relationship is discussed [

32]. Gress and Hall [

32] and Kyle and Chick [

33] explored that sense of place as an individual’s emotional and interpretative reaction to and interaction with a specific physical environment, including the personal meanings assigned to the place. A sense of place related to nature, as Gress and Hall [

32] noted, induces the feelings of integration and inclusion. Moreover, for some individuals, where one lives is a part of their identity.

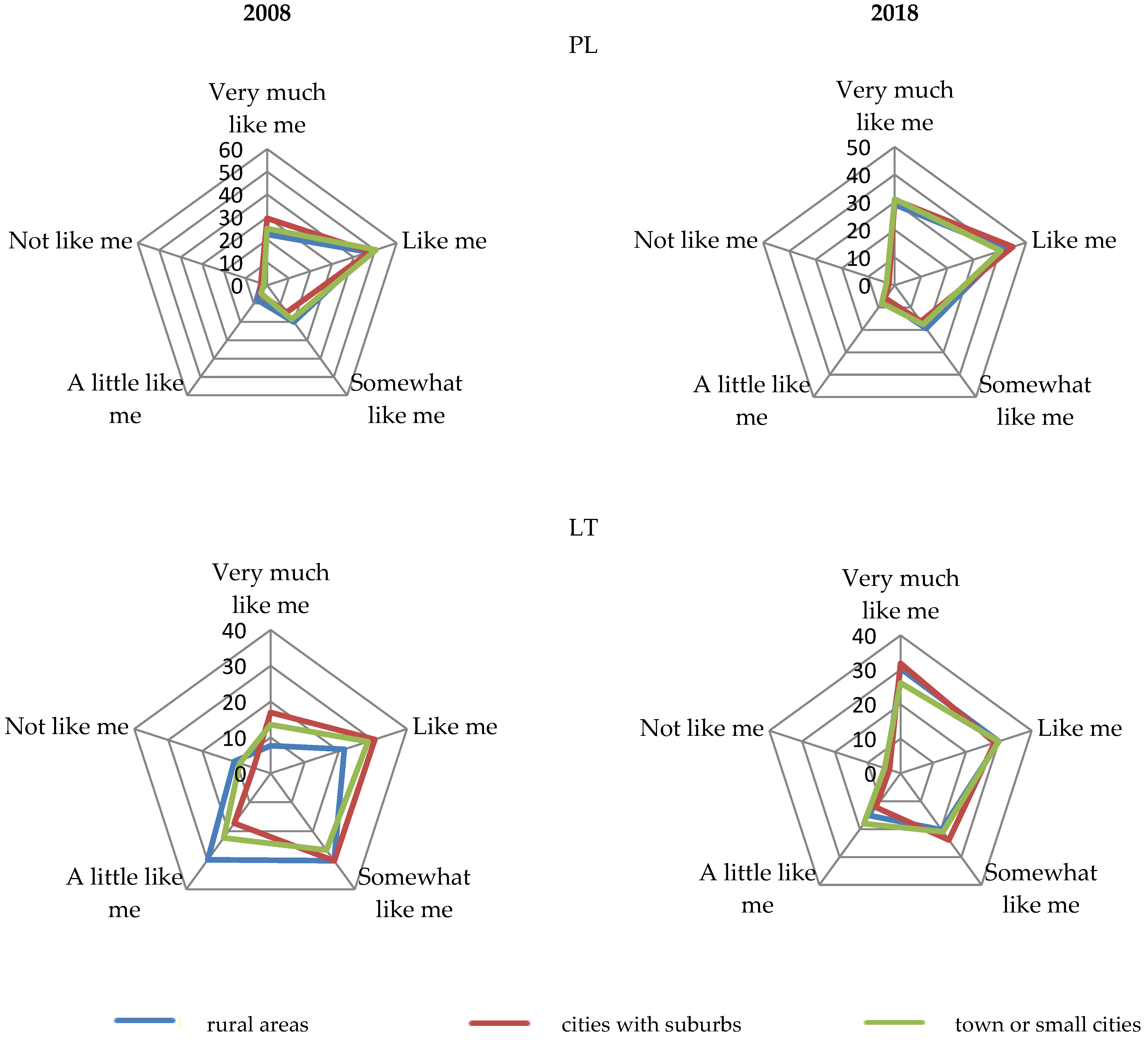

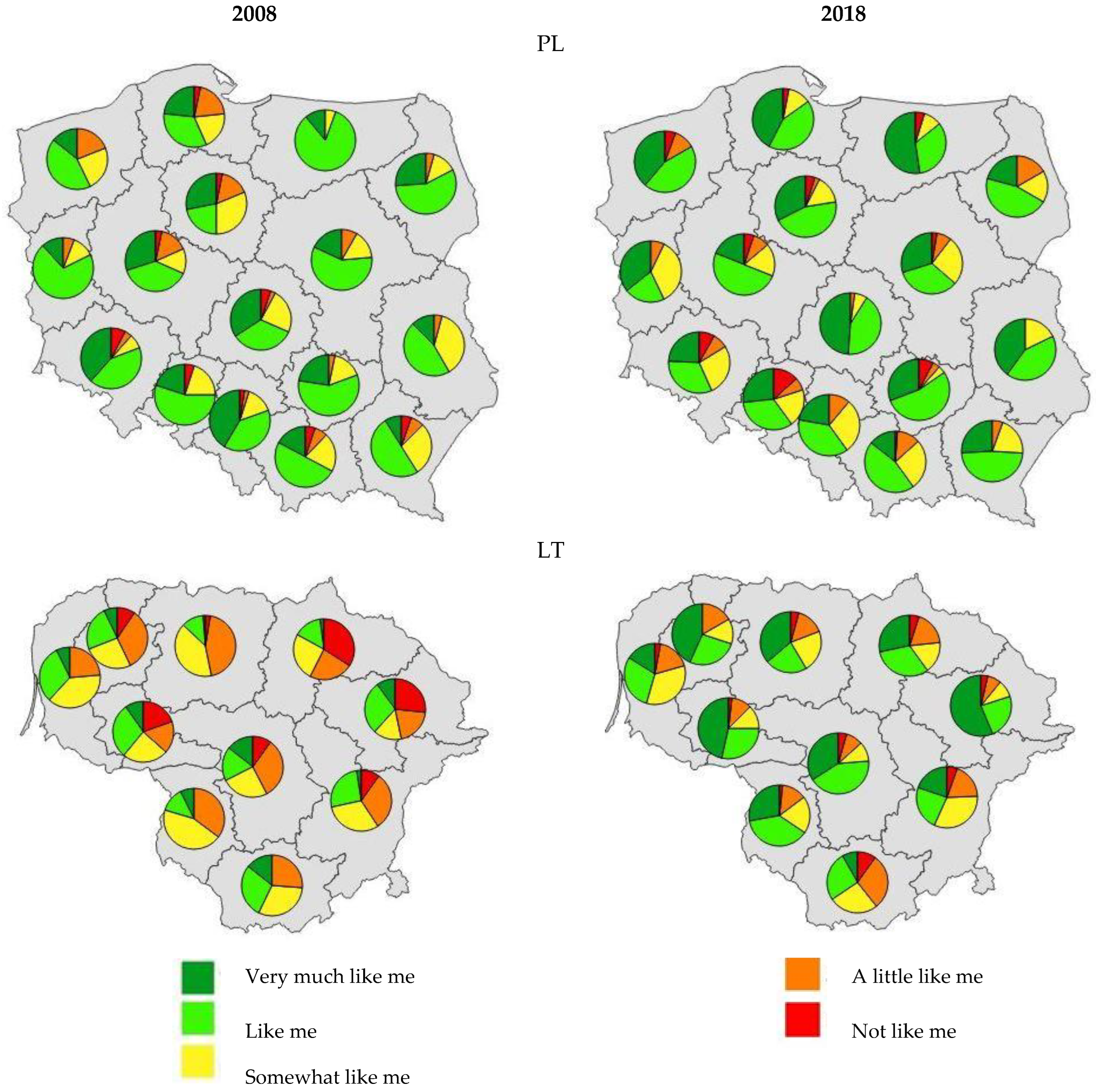

According to the research implemented in the US, the urban and rural population have significantly different attitudes toward environmental issues [

34]. The research has revealed that the rural residents pay more attention to the farmland conservation and less to climate change compared to urban/suburban residents. A strong place identity also has a significant impact in shaping the attitude of the rural population towards environmental conservation. The majority of the rural population usually identify themselves as environmentally conscious persons, but often oppose or have doubts about the existing environmental policies. The rural population is closely linked to the local natural environment and wants to be involved in the management of local resources.

The rural–urban differences and distinction in the evaluation of nature as a value was analyzed by Maller et al. [

35]. They revealed that urban people may have little or no contact with nature if they feel separated from nature and it is not part of their experience. Moreover, this creates the challenge of urban people finding it difficult to value and care for the environment. Similar conclusions can be drawn from the studies on the rural and urban children’s relationship with nature in Mexico [

36]. According to the findings of the study, children living in the countryside (in particular, the girls) have a stronger sense of connection with nature and behave in a more pro-ecological way than the children from the city. In the analysis of activities involving the natural environment, Stewart and Eccleston [

25] found out that the rural residents were more likely to participate than those living in urban areas. This idea is supported by Bashan et al. [

37]. In their study, they found that, regarding the urbanization process, urban lifestyles increased people’s disconnection from nature, referred to by the authors as the “extinction of experience”. These findings highlight that the decreasing opportunity to interact with nature reduces cognitive and affective relations with nature. This leads to an assumption that urban living creates a lower level of nature relatedness and values such as care for nature, sense of belonging to the place, and lower connectedness to nature compared to the rural residents.

According to Farjon et al. [

20], compared to younger people, older people give higher ratings to the naturalness of nature, and a longer experience with nature promotes a high evaluation of nature as a value. Stewart and Eccleston [

25] also found that the respondents aged 35+ were more likely to garden and/or watch or listen to nature programs than on average. This insight is also supported by a few other authors [

28,

31] who proved that even reading or listening about nature also promotes nature as a value feeling, because they feel aware of the environmental issues.

According to the findings of the exploratory study by Nestorová Dická et al. [

12], the personal economic situation, age, education level, and profession influence the locals’ attitude towards nature (mostly national parks based on the focus of the research).

The Europeans have contrasting opinions and experience in dealing with nature. Farjon et al. [

20] noted that the responses from people with a low level of education were rather poor and they were less capable of expressing their perception towards nature as a value and answering environmental questions. This implies that environmental education in various forms can be a good option to promote environmental awareness and experiences.

2.3. Socio-Economic Characteristics and Their Relationship to Care of Nature

Recently, the conflict between economic development, increase in material goods, unstoppable use of natural resources, and environmental pollution has become increasingly noticeable. There is an increasing focus on environmental issues in economically developed countries, with an emphasis on nature as a value. Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that there are very few research studies analyzing in detail the inhabitants’ attitudes towards nature; in particular, in the international context.

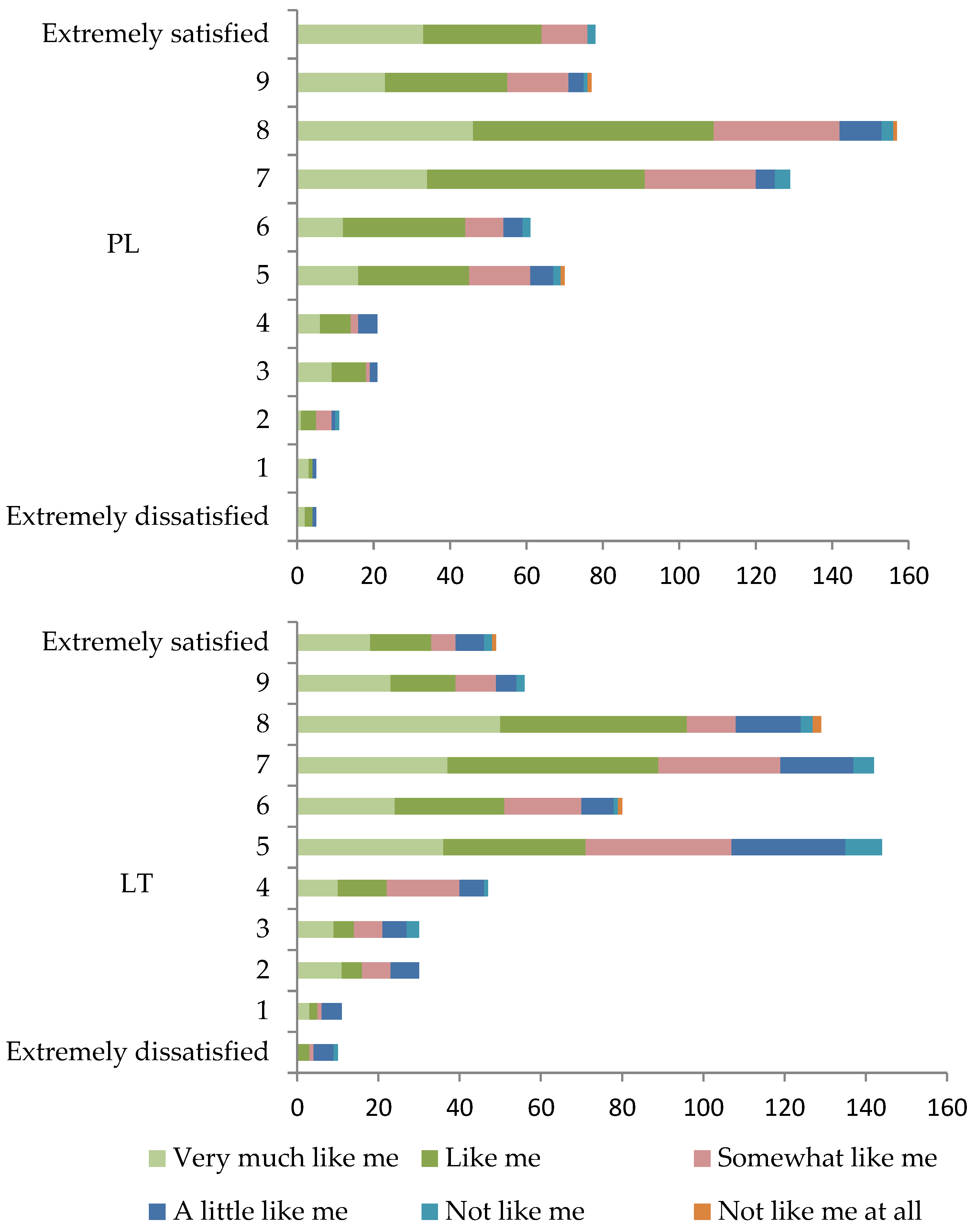

There is a direct link between the formation of a pro-ecological approach, strengthening of environmental awareness, and the income level of the population [

27]. This is due to the increasing demand for organic products and environmental services (such as landscape amenities favorable for recreation). With the rise in living standards in the developed countries and the formation of the middle class, there has been a greater demand for leisure and comfort goods and services, including ecosystem services and, in particular, landscape amenities. People demand companies to reduce pollution and waste, and expect other people to have a more sustainable and pro-environmental approach toward consuming and being in nature [

38]. It should also be noted that pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors are shaped by the application of corporate environmental responsibility principles in the workplaces. Adherence to environmental standards at companies is becoming a marketing tool and a competitive advantage [

39].

The increasing recognition of recreational and health functions of the natural environment reveals the formation of a pro-environmental approach. According to the Scotland People and Nature Survey 2019–2020 [

25], three-quarters of adults agreed that their last outdoor visit helped them “to relax and unwind” (75%) and almost as many strongly agreed that the “experience improved their physical health” (71%) or that the “visit had made them feel energized and revitalized (69%)”.

According to Mears et al. [

31], the accessibility of local greenspace favors people living in more deprived areas. They identified that, for those belonging to minorities (with lower socio-economic status), attractable nature was within walking distance of working-class neighborhoods. However, groups with a higher socio-economic status placed a higher value in relation to the opportunities for individual recreation in nature [

40,

41]. Hence, this signals the importance of location or nature quality and the reasons behind the formation of natural/green places (parks, walking paths, etc.). This can be viewed as a factor of the acceptability of nature for a particular social group or can provide maximal public satisfaction when being in and using nature, employing it as a facilitator for socialization. Moreover, the availability of green space (especially if within walking distance and not requiring any travel expenses) was also mentioned by some scholars as a factor for being in and caring for nature by the deprived area residents [

5,

42].

The findings by Nestorová Dická et al. [

12] support that people working in tourism have more positive views towards nature and the natural parks analyzed by the researchers. This suggests an assumption that, regarding nature-based values, connectedness to nature depend on the person’s economic activity or occupation.

Mears et al. [

31] and DeVille et al. [

28] found that, in the case of higher-income and relatively homogeneous populations, there are limited opportunities to compare them to the urban versus rural perspective in relation to nature. The socio-economic status can become a significant barrier in the formation of childhood nature experiences, which is reflected in the connection with nature in adulthood.

Research conducted by Monus [

43] revealed that the activities by the educational institutions and educational programs have a significant influence on the formation of pro-environmental attitudes and behavior. It was concluded that the factors influencing students’ pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors were related to the students’ socio-economic status, place of residence (type of settlement and region of the country), and parental education.

An analysis of the works by different authors emphasizing the importance of socio-demographic and socio-economic characteristics in caring for nature (

Table 1) has suggested that some of the characteristics were more often repeated in the works of different authors, whereas others were mentioned more in individual cases.

Summarizing the theoretical approaches, different social groups should be mentioned, as nature users have varying preferences and other subjective reasons behind their views towards nature as a value. Moreover, it should be pointed out that population-subjective (individual) characteristics are the factors that highlight their priorities in terms of the care for nature.

Individual’s subjective opinion and attitudes about nature are detailed in many scientific sources. However, the report by Farjon et al. [

20] highlights that, over the past decades, only few international, including several country-based, representative surveys have been carried out to explore changes in the values of nature. Furthermore, according to the findings by DeVille et al. [

28], data gaps and limitations in the exploration of the change in individual perceptions towards nature over time exist even in international literature and cross-sectional studies. Several authors [

5,

28,

31] conducted their own research and agreed that there was a need for subsequent multinational studies in the field of the subjective perception of nature as a value and the reasons behind people using or not using the nature because it depends on various factors.