Abstract

The research and innovation activities at higher education institutions (HEIs) are considered essential in driving forward sustainability in order to facilitate future decision-making. However, a systematic approach regarding sustainability research through administrative efforts is still lacking in HEIs worldwide. Therefore, this manuscript aimed to explore contradictions embedded in the activity systems that hamper the internalization of sustainability research in HEIs. The current study conducted semi-structured interviews with faculty members at a leading research university in Taiwan. The lens of activity theory was used to explore and analyze tensions rooted in the activity systems involved in research and innovation. We found that resources to undertake sustainability-related research have not been allocated in a desirable manner. Moreover, the stakeholders are lacking agency, motivation, and perceived urgency to play their roles in supporting sustainability-related research through their practices. The propositions concluded from this study would help the involved actors to reconfigure their activity systems to make a contribution toward sustainability. This study also serves as a fundamental step towards conducting future empirical studies in contextual theory building directed at co-creating value through sustainability-related research and innovation practices.

1. Introduction

Internalization of an activity takes place when the reason for doing it becomes anchored with broader values, commitments, and interests [1]. This requires the individuals to transform some externally offered norms, values, guidelines, and regulations into their own [2]. Thus, internalization involves a process in which an externally offered phenomenon becomes a more personally endorsed and self-determined regulation [3]. The internalization process enables organizations to update themselves on how they tackle the dynamic institutional demands [4]. Therefore, organizations should be willing and capable to modify and adjust their resources by adding, reconfiguring, and removing certain resources and competencies in order to internalize a new practice such as sustainability [5]. The main objective of the United Nations (UN) agenda 2030 is to foster a transformation in development that requires the internalization of the goals and targets by the potential actors of change [6].

The role of higher education institutions (HEIs), as change agents, has been considered important in achieving the UN agenda 2030 through their major activities including teaching, research, operations, and community outreach [7]. Being agents of change, HEIs drive forward sustainability through problem-oriented, real-world research, critically reflecting on goals, integrating sustainability into research and education, and thus educating future decision-makers [8]. Therefore, HEIs have a major responsibility to function as a catalyst in implementing sustainable activities [9].

The Brundtland report [10] defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. In this connection, UNESCO [11] urges higher education to play a significant role in sustainable development in all regions. Moreover, society is also demanding that HEIs turn themselves into change agents and make certain interventions for sustainability [12,13]. Therefore, HEIs are expected to consider co-designing and co-producing knowledge and tools as their main role in the transformation of society towards sustainability, in collaboration with their stakeholders e.g., industry, government, and society [14].

The UN Agenda 2030 [15] has provided HEIs an opportunity to reshape their mission by including certain values and practices and to rethink their role in terms of education and research [16]. It also provides motivation for directing their efforts towards sustainability in their daily operations, teaching, and research [17]. Sustainable development goals (SDGs) suggested by the United Nations [15] have been generally accepted worldwide as a blueprint for attaining sustainable development in economic, social, and environmental aspects. The SDGs address challenges related to almost all aspects of life in a holistic manner. They play a crucial role in creating a positive impact by embedding sustainability into university strategies, decision-making processes, and practices, and for improving their accountability to stakeholders [18].

Since universities undertake fundamental and applied research in sciences and humanities to improve our understanding of life [19], SDGs serve as an important supporting mechanism to instill sustainable development through their basic and applied research to resolve real-world problems and advocate technological breakthroughs for sustainability [8]. HEIs’ responsibilities in education, research, and innovation are of key importance in helping society tackle major challenges [20].

In 2008, the United Nations identified 17 HEIs around the world to work as an “Academic Impact Hub” for each of the 17 SDGs. The University of Pretoria in South Africa is an example of its innovative engagement and use of research to address societal problems and meet the target of zero hunger (SDG 2). Thus, the establishment of these SDG hubs within the HEIs is an indication of timeliness for strengthening our empirical and conceptual insight regarding the ways to achieve these global goals through higher education [19]. Secondly, academic and professional stakeholders have started to evaluate the universities’ commitment to sustainability in terms of fulfilling the SDGs. The world university ranking agencies have started to turn their mechanisms towards measuring universities’ performance and success on the basis of their efforts directed at delivering these global goals. Horan and O’Regan have shown a list of 25 frameworks currently used for HEI sustainability assessment [21]. The Sustainable Tracking, Assessment and Rating System (STARS), Auditing Instrument for Sustainability in Higher Education (AISHE), and Sustainability Assessment for Higher Technological Education (SAHTE) are some examples of these frameworks. The Times Higher Education (THE) University Impact Rankings has recently started to capture institutions’ environmental, social and economic impact in terms of 17 SDGs. It has recognized more than 1000 universities around the globe for their efforts in dealing with global challenges. University of Manchester (UK) is among the top leading universities, followed by the University of Sydney and two other universities from Australia in a row as per the THE Impact Ranking 2021.

Thirdly, previous researchers such as Filho and his colleagues [22] have urged HEIs to channel their research toward sustainability by considering the SDGs framework. Therefore, an increasing number of universities are trying to align their research and activities with the concept of sustainability [19]. However, sustainability-related research is not yet systematically conducted in HEIs through administrative efforts [23]. As a result, only those researchers who have know-how about the SDGs can relate their research publications to this context, and in many cases the relevant research could not even be linked and labeled as sustainability research [24].

Previous research has tried to investigate the dynamics and solutions for sustainability in the context of HEIs, such as sustainable strategies [25], curriculum and practices [26,27,28], the efficiency of resources [29], governance [30,31], reporting mechanisms [32,33], teaching and learning practice [34], and campus sustainability [35,36]. However, the literature on the internalization of sustainability in research practices at HEIs is still scant. Within this scope, this research aims to explore and unpack the contradictions embedded in the activity systems of sustainability research at HEIs, so that a viable framework can be suggested to foster the internalization of sustainability into their research practices.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Service-Dominant Logic

Service-dominant logic (S-DL) serves as a paradigm in theorizing the roles of organizations and their customers in co-creating value [37]. It conceptualizes the nature of transactions in service as a revised theory of economics and society [38]. This reconceptualization shifts the focus from a goods-dominant logic (G-DL) to the S-DL. The concept of G-DL states that the units of output embed their value during the process of manufacturing [39], whereas the S-DL affirms that the value is co-created by the producers and the customers [40]. The shift from G-DL to S-DL is imperative for organizations to reframe themselves and the role of their stakeholders in value co-creation [41]. S-DL views service as the application of competencies, such as knowledge and skills, for the benefit of other parties [39]. Therefore, service turns into a process by which something is offered for the benefit of the other, in contrast to the units of output produced [41]. Vargo and Lusch (2004) describe resources as the underlying phenomenon for this transition. The authors describe two kinds of resources: operand and operant resources, associated with the dominant logic. Operand resources as those on which an operation or act is performed to produce an effect, whereas the operant resources that are employed on the operand resources or the other operant resources to create an effect [42]. The operant resources, which are intangible (such as organizational processes and core competencies), are primary for the S-DL on the grounds that they produce an effect and contrast the operand resources (such as factors of production in an organization) as a basis for the G-DL [40]. Another important thing in S-DL is a service system that consists of actors, who work in an actor-to-actor (A2A) network, in which actors play their roles in value co-creation for the viability of the service system [43]. S-DL describes a service system with five axioms and 11 foundational premises [44], which are listed in Table 1. below.

Table 1.

Axioms and foundational premises of service-dominant logic.

In S-DL, service is the foundation of social and economic exchange. Each actor withholds certain resources or integrates resources as the value proposition to call for value co-creation activities, which form the service system to execute the business processes. The outcomes of the process are evaluated by the beneficiaries who are actors playing the roles of producers, customers, or suppliers in the service system. The notion of co-creation suggests that value can be determined only when a service is offered, where perception and experience are imperative for the determination of value [45]. Therefore, value is not determined but offered by the organizations as a value proposition [40]. Further, service is a process that is offered for, and in concurrence of, the other party with an intent to obtain a reciprocal benefit, thus turning the primary purpose of the economic exchange [45]. In this way, the operant resources such as knowledge and skills that are applied by the provider embody the vital source of value created [45]. The concept of S-DL has evolved and extended through the efforts of scholars around the world [44]. The intricacies of co-creation of value have been explored by previous studies [46,47] and the concept and implication of S-DL can be traced in the strategy literature [48,49], especially in the resource-based view (RBV) stream [50,51]. Considering the wider strategic implication, S-DL has been used for research in different contexts such as, tourism [41,51], manufacturing [52,53], education [54,55], and higher education [56,57].

2.2. Some Theories Related to S-DL

The management of resources [42] is one of the bases for new theory development on marketing and markets [40]. Keeping in view the work of Constantin and Lusch [42], Vargo and his colleague distinguished resources as operand, and operant resources, and they affirmed that the operant resources are the fundamental basis of exchange. The strategy literature, especially from proposers of the resource-based view [58,59], posits the importance of possessing and utilizing unique, non-transferable, non-imitable, firm-specific resources for the achievement of distinction, and sustainable competitive advantage. Since mixed resources enable organizations to gain distinctive strategic options enabling the managers to gain different levels of economic outputs [59], the RBV suggests that organizations have a bundle of unique resources, such as material, human, organizational, and locational resources and skills towards distinctive value-creating strategies [58]. Previous studies [51,60] have discussed how RBV is related to S-DL and value co-creation. Therefore, many recent studies have considered RBV for research in different contexts including health [61], entrepreneurship [62], insurance [63], manufacturing [64], and higher education [65,66].

Value is co-created in concert with the stakeholder while meeting the expectations promised by the organization [67]. In this connection, the stakeholders’ theory argues that the value is co-created through a joint effort in order to benefit the business and its stakeholders [68]. Thus, the involvement of all the stakeholders is necessary for integrating the resources to resolve the issues related to sustainability [69]. Freeman [70] termed the stakeholder as “…any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives”. However, the theory of stakeholders identification and salience [71] distinguishes stakeholders from non-stakeholders. This model offered three main attributes of a stakeholder and suggests the possession of one or more attributes to become a salient stakeholder. These attributes include: (i) power, which is the probability of an actor to carry out his will despite resistance; (ii) salience which includes socially accepted and expected structures or behaviors; and (iii) urgency which represents the degree to which stakeholders’ claims call for immediate attention. The authors bifurcated the stakeholders based on having all three, a combination of two, or a single attribute. Following are the types of stakeholders as suggested by Mitchell and his colleagues:

- (i)

- Definitive stakeholders possess a combination of all three attributes, such as power, salience, and urgency.

- (ii)

- Dominant stakeholders possess power and legitimacy, but they lack urgency.

- (iii)

- Dependent stakeholders possess legitimacy and urgency, but they lack power.

- (iv)

- Dangerous stakeholders possess power and urgency, but they do not have legitimacy.

- (v)

- Dormant stakeholders are those who only possess power but not legitimacy and urgency.

- (vi)

- Discretionary stakeholders only possess legitimacy without having power and urgency.

- (vii)

- Demanding stakeholders only hold urgency but no power and legitimacy.

Keeping the significance of stakeholders in view, many scholars have conducted stakeholder-related studies in different contexts, such as higher education [72]. Further, a recent study [73] has discussed the way relevant stakeholders can be involved in a co-creation process in promoting sustainable consumption in HEIs. Thus, the consideration of the involvement of stakeholders is imperative in the co-creation processes at HEIs.

Information is one of the sources for providing value by informing and educating the stakeholders so that they make faster and more informed decisions [74]. However, there is also a condition in which different people have knowledge of different things [75]. Such a situation where different actors hold different types of market knowledge [76] is termed as information asymmetry [77,78], which can be a way to overcome information asymmetry [78]. Market signaling is the process of establishing a relationship of offering or providing incentives to persuade a party with private information in order to encourage information sharing [79]. Another way to overcome asymmetric information is market screening [79], which serves the idea that the party with less information should initiate and try to seek and obtain the lacking information. In this connection, the information orientation, such as acquisition and dissemination of information, is helpful in reducing information asymmetry [80] so that the stakeholders may be able to make informed decisions.

2.3. Activity Theory and Agency

Activity theory is one of the latest perspectives to work on analyzing and redesigning collaborative activities and social networks [81]. The Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) can be traced back to the work of Vygotsky in 1978 [82] and has been increasingly cited in multidisciplinary research, such as in education, workplace learning and transformation, and human-computer interaction, in past decades [83]. Vygotsky conceptualized the activity theory as a combination of a subject, mediating artifact (tools), and an object (the task or activity) and thereby introduced the concept of a mediated act. The basic concept which was coined by Vygotsky was the mediation of tools between the subject and object, i.e., to facilitate the subject to obtain the object and achieve the outcome. Then, Leont’ev, in 1978 [84], conceived that the model presented by Vygotsky does not deal with the relationship between the individuals and their respective environments in which the activity is performed. Engeström extended Leont’ev’s model by adding rules, community, and division of labor, where the relationship between a subject and their community is mediated by the rules, and the relationship between community and object is mediated by the division of labor [85].

While these activity theories focus on the individual activities system, Engeström intended to develop a model to understand the network of interacting activity systems [86]. Thus, he expanded his earlier model by focusing on the multiple activity systems as a unit of analysis from the individual activity system and visualized the third-generation activity theory by integrating two activity systems ([87], p. 136).

Thus, the third-generation activity theory went beyond the boundaries of a single activity system and adopted multiple activity systems as a unit of analysis with mutual interaction and collaboration between the systems [81]. This development focuses on the mechanism and dynamics of the subject directed towards the analysis of agency, experience, and emotions. Therefore, the model is an intervention to generate a collective agency among the practitioners, who face challenges in remodeling their activity systems [88].

The work of Engeström on activity theory paved the way for research and reconceptualized the human as the starting point of the activity, thereby identifying human agency as the central role. The human agency, from the activity theory standpoint of Engestrom in the form of subject, consists of potentialities and positions for developing a new tool to form activity towards a better future [89]. Thus, the cultural-historical activity theory is a mediation between intentionality and agency [90] among other factors. Therefore, the agency is shared among different actors including university researchers and students in a pleasant and synchronized way [91].

Activity theory is a “philosophical and cross-disciplinary framework” that can be used in studying various human practices, which are simultaneously interlinked at individual and social levels [92]. According to Leont’ev’s work, the activities are generally long-term arrangements, and the objects are transformed into the outcomes through multiple phases and steps. Thus, the activities are considered as a collection of individual actions, which are inter-related by virtue of the common motive and object. Performing an activity means that there are conscious actions with a certain goal. An action consists of different operations in which the performance of the action depends upon the conditions and the context of the action [91]. The concept and functioning mechanism of activity theory conceptualized by Leont’ev has been visualized through a figure by Hasan and Kazlauskas ([93], p. 10).

The cultural-historical activity theory is a viable design for studying the complexities and contradictions in authentic work environments [94]. Thus, this framework has been widely used for research in different areas of study for the last several decades. There are several recent examples of using activity theory as an analytical tool in different areas of research, such as in medicine [94,95], education [96], computer science [97], human-computer interaction [98], information systems [99], service science [100], and higher education [101]. Thus, activity theory can be used in studies across different disciplines and contexts.

2.4. Contradictions in Activity Systems

Contradictions can be helpful to identify the areas that require investigation to understand what is going on in an activity system [85]. A contradiction does not necessarily mean that a problem or a certain conflict is occurring, but that there are structural pressures historically occurring within or among the activity systems [87]. The activity theory [85] classifies contradictions into four categories:

- (1)

- Primary contradictions are those that occur within an individual node of the activity model. If we relate these contradictions with the hierarchical level of the activity, it may lie in the action or the set of actions undergoing in an activity. These contradictions occur when multiple actions are performed by an individual under different activities and situations, or the same action is performed by different individuals with different motives or goals [102].

- (2)

- Secondary contradictions occur between two nodes of the activity system, e.g., between subject and tools, tools and object, subject and rules, rules and community, etc.

- (3)

- Tertiary contradictions occur between an existing activity and one that can be a culturally improved version of the same activity. Such contradictions are intentionally developed by seeking examples and envisioning the existing activity towards developing improved artifacts, division of labor, or a new community.

- (4)

- Quaternary contradictions occur between the considered activity and the other activities running in the meantime. Thus, the term contradiction in the activity theory indicates a mismatch between the nodes in developmental phases of an activity, or between different activities, and are considered as sources of development [92].

The activity theory provides a framework to explore the underlying dynamics of an activity system. Thus, this framework was used in our study to understand the underlying tensions embedded in the activity system undertaken by the faculty while internalizing sustainability in their research.

3. Methodology

The objective of this study is “to explore and unpack the contradictions embedded in the activity systems of sustainability research in HEIs”. To achieve this objective, a qualitative study is required to explore and understand the perspectives of actors associated with this activity system in HEIs. Therefore, this study adopted qualitative research as used by previous studies in sustainability research [28,103]. The qualitative method was adopted on the following grounds. First, the research question is explanatory in nature and requires a thorough understanding of the phenomenon from the perspectives of the experts, thus supporting the use of in-depth interviews. Secondly, the activity system of research involves interactions with multiple stakeholders, including individuals, groups, organizations, technologies, and other activity systems. Thus, the qualitative method is required to unfold the underlying tensions within and among activity systems.

The data were collected through in-depth interviews with the faculty members at a renowned research university in Taiwan. Since the university has obtained a significant recognition for its sustainability in Taiwan, and the efforts and progress on sustainability-related research from its faculty could represent the perspectives and experience of research frontliners in sustainability.

We organized and asked the interview questions using the Focused Conversation method, also called the Objective, Reflective, Interpretive, and Decisional (ORID) method [104]. This method has been based on the experiential learning models and uses questions at four levels [105] as follows:

- i.

- Objective: questions about facts and external reality.

- ii.

- Reflective: questions to seek personal reaction to the data, an internal response, emotions or feelings, hidden images, and associations with the fact.

- iii.

- Interpretive: questions to draw out meaning, values, significance, and implications.

- iv.

- Decisional: questions to elicit resolution, bring a conversation to a close, and enable the group to make a resolution about the future.

The Focused Conversation method provides a structure and framework to carry out a meaningful discussion. It is widely used in a variety of conversations, such as expert consultations [106], classroom discussions [107], meetings [108], and research interviews [109,110]. Therefore, it is suggested to use the Focused Conversation method in research interviews [110] based on the following grounds:

- i.

- The method contributes to the thinking process, which prevents a conversation from drifting aimlessly along.

- ii.

- It is versatile and works with people of mixed backgrounds, ages, and varying levels of acquaintance, from total strangers to long-term colleagues.

- iii.

- It provides an excellent way to focus people on a topic long enough to determine what direction is needed. This kind of focus is a time-saver, and often a saver of psychological energy.

- iv.

- It provides room for genuine listening while avoiding negative thinking.

- v.

- It allows honesty.

The interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were carefully analyzed by using the lens of contradictions as prescribed by the activity theory [86].

4. Interview Participants

Faculty members, being active researchers, are important actors in their service system. These faculty members have their agency and have accumulated contextual factors for a long time through their knowledge, experiences, and expertise in their respective fields of study. Therefore, the participants of this study are faculty members, who are experts in various domains of research on energy and the environment, at a research university in Taiwan. The interviewees were selected purposefully based on their research areas related to SDGs 7 and 13 and their research works had been highlighted by the sustainability annual report published by the university in 2021. The sample consisted of experts, including distinguished professors, professors, and assistant professors with a myriad of experience and knowledge in their domain of expertise. The research areas of the interview participants are shown in Table 2, below.

Table 2.

Research areas of interview participants.

4.1. Professors from Science and Engineering

A total of 10 faculty members from science and engineering participated in this study including 2 distinguished professors, 7 professors, and 1 assistant professor. These faculty members have a variety of research expertise, such as degradation, photodegradation, nanocomposites, nuclear energy, nuclear safety, radiation safety, nanoelectronics and semiconductors, solar cells, water chemistry, electrochemistry, metals and alloys, biosensors, microfluidic systems, and biochips. They had been contributing to sustainability in collaboration with other individuals, labs, and organizations within the country and abroad. Apart from their research, some faculty members had also actively supported and promoted sustainability in the areas of energy and environment through a range of other activities, such as political campaigns, writing different articles highlighting the issue, lectures outside the campus, TV interviews, and debates, news commentaries through mainstream and social media, and organizing and supporting referendums.

The major research areas of the participants include electrolytic water splitting, energy storage devices, nanogenerators, water decontamination, high-performance battery materials, earth-abundant materials, and semiconductors. Besides their research contributions, they had also been involved in advocacy on sustainability to students, government, and society in order to support their cause. They had been working on a variety of research projects in their respective fields of study, funded by the ministry of science and technology (MOST). They had also been involved in active research collaborations with research labs and other stakeholders nationally, and internationally.

4.2. Professors from Management

The interview participant from the management discipline was a professor with a background in energy and climate law for science and technology. His main research focus was energy and environmental law with certain potential outcomes i.e., overall sustainable development governance, improved rule of law and investment security, and the growth of Taiwan’s local green energy and climate change industry. Apart from his research on the law regarding SDGs 7, and 13, he had also been extending his expertise for amendments in the law, influencing the government for appropriate policymaking in his domain, writing commentaries on media, offering and teaching courses on sustainable development, launching awareness campaigns, and inviting professors from Asia and Europe to discuss issues on energy and climate law. He had also been active in collaboration with one of the political parties in Taiwan to propose bills to improve the rule of law in renewable energy governance and to provide a legal opinion on such matters.

These faculty members, being agents of sustainability research, had underwent a complete activity system that helps them to achieve their research goals. Figure 1 exhibits the activity system of the faculty members in pursuing their research on sustainability.

Figure 1.

Activity diagram of faculty pursuing sustainability research.

5. Research Findings and Explanation

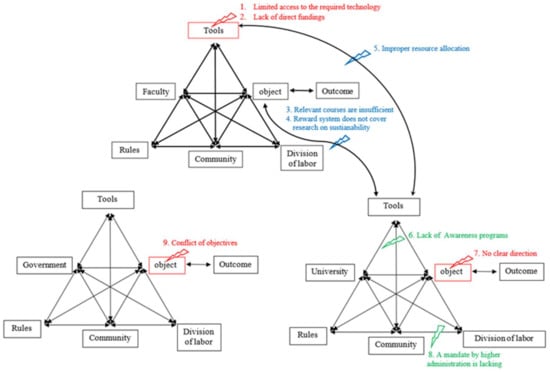

With the growing global interest in sustainability, expedited by the introduction of the SDGs framework by the UN in 2015, the role of HEIs as change leaders has also expanded. The expectations of stakeholders are triggering HEIs’ service systems in playing their role effectively and timely, by integrating the essence of sustainability in their major activities. Some of these activities include education, research, campus operations, and community participation. Research and innovation are the pivotal functions through which HEIs seek optimal solutions for the problems emerging in the real world. Faculty at universities are the main agents who drive forward research and innovation as part of their major activities. These activities require several interactions with other human and non-human actors including individuals, groups, labs, technologies, organizations, and communities. In doing so, several contradictions occur within and among activity systems. The activity diagram shown in Figure 2 highlights the contradictions existing in the activity system of the faculty members in pursuing their research on sustainability.

Figure 2.

Contradictions in internalizing sustainability in research.

The following are contradictions that we found in the activity systems of research while integrating sustainability.

5.1. Limited Resources for Research Projects in Sustainability

From the interview, some professors mentioned the shortage of resources for their projects in sustainability. We concluded two contradictions: #1, limited access to the required technology; #2, lack of direct funding.

From the interviews, we found that the faculty have research ideas on sustainability in the areas of energy and environment that may support SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy) and SDG 13 (climate action); however, the required technology is not available to implement their ideas (contradiction #1 on the tool). In some cases, although technology is available, to access that technology is also very expensive. This can be witnessed from the following comments of a professor during the interview.

We need some very good microscopes and investigating instruments to measure or study the properties of the materials. The instrument itself is very expensive. We do not own the instrument, but the university has some common facilities we can access. However, the cost to access this expensive instrument is also high. (Excerpt from the interview of P9).

The faculty felt that there was a lack of technology and infrastructure to find more viable solutions for the problems regarding sustainability because such technology, especially in the field of semiconductors, is too expensive; thus, they are unable to acquire that technological facility. This university has some facilities for common use by all the researchers. However, the high cost of using that facility is a major barrier to conducting relevant experiments. According to some faculty, there is also a need for information technology (IT) or artificial intelligence (AI) to foster technological interactions for sharing emerging problems and their possible solutions. This limited access to the required technology is an obstacle for the researchers to achieve their research objectives regarding sustainability issues. The main reason for the disconnection of the researchers and the required technological facilities is the cost of that technology. This cost undermines the ability of researchers to make better use of this technology in terms of proposing optimal solutions for sustainability-related problems.

Finances are always important for any activity system to move on. Funds are equally important for the faculty members or researchers to carry forward their research activities. According to the faculty, many research problems require interventions in the domains of environment and energy. However, the faculty feels that the accomplishment of their ideas is restrained by financial constraints (contradiction #2 on the tool). A major problem the researchers face is that their ideas in these domains are not much appreciated for funding. Funding proposals in such areas are given less consideration and so, in some cases, faculty deliberate on alternate arrangements to indirectly support their idea. An example of such a case is evident in the following words of a professor:

I focus on the environment, and it is very difficult for us to get money to support our lab to move on. That’s the practical thing. Even though I know that the work on environmental issues is good, sometimes people don’t appreciate our work. So, I try to find an alternate solution for some sufficient funding, and then I use these funds back to the environment (Excerpt from the interview of P1).

In other cases, professors who are working on proposing some innovative technology for emerging sustainability issues also face financial constraints. According to them, many of their technological solutions do not get realized as the manufacturing and testing of their prototypes require connections with the industry to use their facilities. However, financial requirements hamper their efforts toward the launch of such technological solutions.

We need to connect our lab with the industry. So, for this kind of bridging, we need a budget in order to create a small production system or to conduct some reliable tests. We need some budget that would enable us to launch that product (Excerpt from the interview of P5).

The availability of funding opportunities may help researchers to offer long-lasting solutions for sustainability-related issues. However, the faculty feels that the relevant stakeholders do not have enough feelings for the issues, which may have a counter effect in the long run. In many cases, authorities do not think about an action unless the adverse effect of a situation is visible. Therefore, priorities of funds are more inclined towards a visible solution for a current problem than a long-lasting, sustainable solution for the potential adverse effects caused by current actions. For instance, research projects in the medical area are much more appreciated than those in the field of the environment that try to safeguard masses from potential upcoming threats. Thus, the priorities for funding are yet to be reset for fostering research and innovation activities toward a sustainable future.

The contradictions #1 and #2, shown in Figure 2, are primary tensions within the tools necessary for the faculty to undertake their research. These tools are part of the resources (i.e., financial and technological), that are generally allocated by the organizations, including the university and outside funding agencies, to support their research activities on topics regarding sustainability. The faculty members are said to be the most eminent stakeholders of HEI [111] due to the coherence of their activities with institutional goals [112]. However, according to the stakeholder model of salience [71], a stakeholder should possess a combination of three attributes to become the most salient stakeholder, which Mitchell and his colleagues termed as a definitive stakeholder. These attributes include power (the probability of an actor to carry out his will despite resistance, salience (socially accepted and expected structures or behaviors), and urgency (the degree to which stakeholder claims call for immediate attention). As universities undertake fundamental and applied research in sciences and humanities to improve our understanding of life [19] the faculty derive their legitimacy from the provision of viable solutions to emerging issues through their research activities, as expected of their profession. Being the agents of change, HEIs drive forward sustainability through problem-oriented real-world research, and by integrating sustainability into research, and educating future decision-makers [8]. Moreover, HEIs have been considered important in achieving the 2030 agenda [15] through their major activities, including teaching, research, operations, and community outreach [7]. This creates an urgency for faculty members to direct their research activities in order to assist HEIs in achieving the 2030 agenda. However, such activities have been hindered by the lack of funding opportunities and access to the technology as required by the faculty to undertake sustainability research. Here involves the power attribute of the stakeholders’ salience. The faculty are lacking their perceived power to influence the managers and other relevant resource providers to obtain financial and technological resources to meet their objectives. In this situation, their urgent and legitimate claims with low power make them dependent stakeholders [71], where they are dependent on universities and other funding authorities and agencies to carry out their will.

5.2. Contradictions between University and Faculty in Sustainability Research and Teaching

We identified two contradictions that mainly came from the resources the university used and the object of faculty in sustainability. Contradiction #3 defines the way in which courses on offer relating to sustainability are insufficient, while contradiction #4 describes a reward system for faculty that does not cover research outcomes in sustainability. We specify these as follows.

Students, being one of the main stakeholders, should have their considerable part in academic research. They should have enough concepts and understanding in their respective areas to contribute to knowledge creation in terms of research activities in their domain. Certain academic tools, such as relevant courses, play their part in imparting such kinds of concepts and developing their understanding as a base for the required research output. Faculty (e.g., P1, P3, P4, P5, P7, P10) have pointed out that the university does not offer enough courses to teach sustainability at different degree levels (contradiction #3 between university’s tool and faculty’s object), which is required for enabling the students to grasp the concepts and help in resolving sustainability-related issues.

For the academic side, we must work on offering some quality courses, to introduce some new courses. I think this is one possibility to make students have sustainability concepts (Excerpt from the interview of P5).

Professors feel that there should be some courses on sustainability to be taken by the students as a credit requirement. These courses should include concepts related to SDGs so that students may have a holistic understanding of the sustainability framework. The absence of such courses encumbers the students’ knowledge creation abilities as well as their abilities to collaborate with the community for a synergistic outcome.

We can have some courses on the sustainable environment for the students to have more understanding of the SDGs, what they can do to help, and what they can do to get connected with the international community on the issues (Excerpt from the interview of P4).

According to the faculty, students have a limited inclination toward academic research on sustainability during the pursuit of their degrees. However, this may be fixed to a certain extent by at least offering some seminar courses.

In general, a reward system is an effective mechanism used by organizations to persuade their members to increase their efforts towards their objectives. The faculty members at this university (e.g., P1, P4, P5, P6, P7, P8, P9, P10, P11) feel that there is a lack of appreciation or recognition for the scientific work on sustainability (contradiction #4 between the university’s tool and the faculty’s object). The university does not offer any incentives to motivate faculty to work together on sustainability-related issues. These faculty members think that some kind of reward would be a tool to motivate them to direct their efforts towards sustainability-related work.

There should be a kind of reinforcement to increase motivation. We must take those kinds of steps. Otherwise, we won’t get enough response. That’s not only for Taiwan but for the universities around the world, because professors are lazy (Excerpt from the interview of P8).

According to P6, SDGs should be linked with the approval of science projects, graduate theses, and the students’ evaluation system. They emphasize the need to make it mandatory for faculty and students to include sustainability-related elements in their research projects. They even accentuate making it part of the students’ evaluation process as well as the faculty promotion system.

We have to make it mandatory like if you don’t select it, you cannot submit a science project, you cannot submit a thesis. Don’t keep it just as a suggestion, or keep it as an option for them. No. Whenever they submit a project, a thesis, or a proposal, ask them to check out the checklist. Then maybe a few years later, everybody will know that they have to do it. But currently, nobody asked us to do this (Excerpt from the interview of P6).

The university needs to have a proper reward system to promote the internalization of sustainability in the scholarly work of the faculty. However, the absence of such a system is a quaternary contradiction between the tools used by the university in promoting sustainability-related research and the internalization of sustainability by the faculty as an object of the research activity system. This tension between both activity systems is also an impediment to the internalization of sustainability in research.

Certain causes necessitate a proper reward mechanism to be in place at the university regarding sustainability-related work. The primary reason is that people at the university including faculty, students, and administration don’t believe that a certain activity is good or bad for the future. The mindset on sustainability is lacking among people on campus; therefore, they don’t feel motivated to put their efforts into working for sustainability. Most of the professors are busy and they feel it troublesome to bring such concepts into their existing domain of interest. Faculty, such as P1, point out that most of the faculty members like to be followers rather than to be pioneers. The situation identifies a lack of self-choice and motivation to adopt sustainability as their goals.

The contradictions #3 and #4 (in Figure 2) are quaternary tensions between the tools used by the university in supporting the object of the faculty. The curriculum-related tasks (regarding contradiction #3) such as curriculum design, course selection, and course evaluation lie under the division of curriculum in the office of academic affairs. Since the absence of sustainability-related courses is an obstacle for the faculty to internalize sustainability in their research, it is up to the university to design and offer such courses to cultivate sustainability-related concepts in the students directed at enhancing their inclination towards, and engagement in, sustainability projects. According to market signaling theory [78], one’s education credentials are considered as a signal for the ability and competence of that person to produce certain performance outcomes. Thus, the absence of such courses limits the signal for the faculty and administration to identify certain students with relevant knowledge and understanding to engage them with sustainability-related endeavors. Therefore, Chang and his colleague [26] emphasize the integration of SDGs and sustainability-related concepts into the curriculum of higher education.

Sustainability has been accepted as a global phenomenon for directing our current activities and actions towards a more favorable future. Therefore, all the actors in society, including HEIs, have been expected to adopt the concept of sustainability as a priority. In this regard, higher education is urged to play a significant role in sustainable development in all regions [11]. Moreover, society also demands that HEIs turn themselves into change agents and make certain interventions for sustainability [12,13]. However, sustainability-related research has not been conducted in HEIs systematically [23], which, according to faculty, is due to the absence of a reinforcement or reward system at the university (Contradiction # 4 in Figure 2). In the current case, the faculty feel busy with research activities in their domain of interest, and they feel it is cumbersome to make efforts in integrating the concept of sustainability in their research unless certain rewards are attached or expected in doing so. This shows that their endeavors towards internalization of sustainability in their research is contingent upon external drive. Such endeavors are termed as extrinsic aspirations [2], which are instrumental to the fulfillment of unmet needs. Ryan and his colleague further explain that such kinds of aspirations and goals are attached to the attainment of material goods, power, fame, maintaining attractiveness, and outer image. The self-determination theory [2] articulates that the way rewards systems are executed will have a predictable influence on the behaviors of the recipients and their motivation. Further, the reward administered to concede the employees’ accomplishments, or their achievements, will support the enhancement of their intrinsic motivation.

However, administrative support and the absence of structural units, such as committees, are major impediments to the implementation of SDGs in these institutions [113]. This is the evidence of the administration at universities being a salient stakeholder in the execution of sustainability in academic activities. When we look through the lens of the stakeholder theory of salience [71], the administration has the power as well as the legitimacy as vested by the university’s governance system, to decide about a portfolio of academic activities aligned with the contemporary needs. However, the administration has not felt the urgency of transforming the curriculum to orient students’ learning in sustainability subjects and establishing recognition incentive systems to boost faculty in shifting their research directions on sustainability.

5.3. Improper Resource Allocation from the University

Among other sources of income, the university is the major financial source for faculty to accelerate their research endeavors. However, faculty such as, P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, P8, P9, and P11, witnessed that the Office of Research and Development of their university had not yet taken any reasonable steps to allocate some finances for sustainability-related research (contradiction #5, between university tool and faculty tool). This can be witnessed in the words of P8 as follows.

I think one particular item the university level can do is that they may put in some research funding for professors. It doesn’t have to be a very large amount, but a certain amount of research funding to be used by the participating professors. It would encourage and promote their participation in SDGs. I think that’s what the university level can do. But I’m wondering if the university authorities would put in this kind of money for supporting SDGs (Excerpt from the interview of P8).

Faculty feel that there is a need for allocating some funds by the university to attract their participation in sustainability-related work. It would enable the faculty to consider sustainability-related elements in their scholarly work. They also point out that the university needs to invest a certain amount to put things together in the area of sustainability. According to them, an allocation of such a budget may also enhance cross-disciplinary research.

University needs to provide some research funding for faculty to help them coordinate with professors from different fields (Excerpt from the interview of P11).

However, due to the absence of such a financial resource, the faculty is currently focusing on other research projects, backed by enough of a financial budget, to support their labs. Some of the faculty members, for example, P1, who are intrinsically motivated for sustainability-related research, try to seek alternative sources of finance to support their activities on sustainability research. The interview participants (e.g., P6) mentioned that most of the faculty members felt it cumbersome to do without allocating some funds. Therefore, they urge the university to allocate a certain amount of funding to channel their research activity towards sustainability in an organic manner.

There is tension between the activity systems of faculty and the university in terms of their tools directed at sustainability research. Thus, a quaternary contradiction exists between the tools of both activity systems (i.e., faculty and the university). Funding required by the faculty to be utilized as a tool to internalize sustainability research is expected by the university. However, the provision of funds by the university as a tool to promote research activities is not currently directed towards sustainability.

The major cause for this contradiction is not actually the university’s financial constraints. The university has been supporting a number of research projects each year. However, the university has not yet diverted its policy attention to prioritizing sustainability-related research in its financial budget. The university has finances as well as talents, but the budget needs to be redirected. In this connection, the issues related to sustainability will attain increased importance and priority on the basis of organizations’ decisions on where to allocate their slack institutional resources [114].

Moreover, organizations need to manage relationships with the stakeholders to understand what they consider valuable, so that the organizational resources would appropriately be allocated to meet their demands [112]. This process of managing stakeholders deals with the complex and broad aspects that help the organization to maintain justice in resource allocation [115], and the efficiency of this resource allocation can be increased through information about the stakeholders’ preferences [116]. Although faculty are the prominent stakeholders of their institutions [111], there is a more dispersed relationship of faculty with their institutions despite having high power in executing the organizational mission [117]. Administrative support is considered to be one of the major impediments to the implementation of sustainability in HEIs [113], and management in HEIs generally does not perceive sustainability as a priority [118]. Thus, the administrative role of optimizing resource allocation may be hampered by a lack of their perceived urgency, as proposed by the stakeholders’ theory of salience [71]. This shows how the institutionalization of sustainability has not been formally recognized in institutional planning, thereby limiting the resources that are allocated for its execution, whereas the prioritization of other projects hampers the integration of sustainability in higher education [118].

5.4. Lack of Awareness of Sustainability on Campus

Faculty, including P2, P6, P7, P9, P10, and P11, feel that there is a need to raise awareness of the major stakeholders such as faculty, students, government, and industry about the importance of sustainability (Contradiction #6, between tools and community). The university should take its part in making people understand the essence of sustainability and its possible effects on our future. There is a lack of activities to spread information about sustainability and the SDGs framework. The university needs to use certain effective tools to promote sustainability research. However, such programs are not currently prevailing in this university.

I have to say that act as a priest and give a talk, a speech or a good lecture to everyone at the university. Otherwise, if we use an email or website, nobody will visit. Because right now you see there is an information explosion. When you open your email or Facebook, a lot of information is there. It is not easy to justify what is important, and what is good for you because there is an information overload (Excerpt from the interview of P7).

There is a need to organize workshops or campaigns to harness maximum efforts from the stakeholders to internalize sustainability into their research. On the other hand, many faculty and students have already been working on sustainability-related issues, but they are unaware of relating and documenting it as sustainability-related work. The university is currently using the means of the internet, such as its website, to provide awareness and to document the research work on sustainability. However, the university is expected to put more effort on reaching out to the stakeholders to educate them for greater output. Thus, there is a secondary contradiction (contradiction #6 in Figure 2) in the university’s activity system i.e., among the tools used by the university to involve and engage its community towards sustainability research.

In this context, it is evident that there is an information asymmetry [77] between the university and its community regarding sustainability. Information asymmetry is a condition where different people have knowledge of different things [75]. In other words, information asymmetry arises when different actors hold different types of market knowledge [76]. The selection of a solution to reduce or exploit an information asymmetry is reliant upon the intent and motivation of focal actors [119]. However, creating a feasible environment between the organizations and their employees regarding information (such as training, and employee participation) has not been focused on by most organizations as a performance-enhancing practice [119]. Previous research [77,78] has revealed that information asymmetry linked with unobservable attributes can be curtailed through information signals. Such signals may be in the form of certain actions undertaken by managers and their organizations [119]. Therefore, there is a need for communication in the form of a specific or a public statement to influence the stakeholders [120]. Thus, a similar kind of communication or information sharing is also required in this university to reduce the information asymmetry between the university and its stakeholders (especially faculty) regarding sustainability-related work. However, certain structural barriers impede the process of involving employees possessing some specialized knowledge [121] and widens the gap between the organization and its stakeholders [122]. Such strategic barriers to information sharing hamper the delivery of perfect information to the organization’s stakeholders [119]. Therefore, it is favorable to resolve the information asymmetry by the focal actor through some pre-commitments, i.e., by demonstrating some truthful, and serious actions to the other actors [123]. However, there is a lack of such actions at this university (as identified by the faculty) that can be caused by the lack of perceived urgency, as articulated by stakeholders’ theory of salience [71], in the university administration for sustainability-related work.

5.5. University Lacks Mandate and a Clear Direction toward Sustainability

Taking the university as the subject of the activity toward a sustainability objective, we identified two contradictions: #7, which speaks to the university as an object that does not have a clear direction toward sustainability; and #8, speaking to community and a division of labor, that the university lacks a mandate from the higher administration.

Faculty e.g., P1, P2, P3, and P10, identified how the university does not have comprehensive thinking on sustainability. Currently, the university does not have a common goal that complies with sustainability and thus does not have a set direction for sustainability-related research (contradiction #7, on the university’s object). The faculty members also point out that there is a need for a clear direction in terms of some vivid topics for different disciplines to work together so that the concept of sustainability can be adopted in academic research synergistically.

The majority of the people know the issue that sustainability is important for our future, for our offspring, or our sons, daughters, grandsons, and granddaughters. And what we are doing now is their future. If you care about them, you should do something about it. So, the university is now in charge of the whole society. Then, it has to take major actions to call for a direction. And I will say that the progress is still slow (Excerpt from the interview of P2).

Moreover, the research activities are fragmented due to a lack of a clear direction from the university’s side. It shows that there is tension within the object of the university’s activity system (contradiction #7 in Figure 2), forming a primary contradiction. Therefore, the university is required to set a direction and strive to put things into perspective, so that people can realize the concept of sustainability and generate new ideas.

We found in this study that there is a need for a common goal by the university that would provide the faculty with a unified direction to work on sustainability, synergistically. Goals are generally considered as essential tools for employees’ motivation and performance in organizations. The importance of goal setting based on four underlying mechanisms [124] that; (i) they provide a direction and attention toward goal-relevant activities, (ii) they have an energizing function, (iii) they have the ability to affect persistence, and (iv) they influence actions by leading the arousal, discovery, and use of task-relevant knowledge and strategies. Moreover, the concept of management by objectives (MBO) [125] postulates the process of formulating specific objectives by the organizations, conveying these to organizational members, and deciding how to achieve those objectives. Since goals provide direction for the managers in planning and developing strategies, and directing organizational activities [126], almost every modern organization considers the formulation of specific goals as part of their systems thinking and strategic planning [127]. However, the faculty in this study identified that there is a lack of a specific common goal or direction with respect to directing academic and other activities towards sustainability. The university administration has the power and the legitimacy to set direction in order to channel the organizational activities on a specific pathway to achieve sustainability given its particular context. However, the lack of management’s perceived urgency [71] for sustainability-related work, is one of the factors that impede the specific goals setting for the university.

Contradiction #8 (Figure 2) denotes a secondary contradiction between community and division of labor in the university’s activity system. It is evident from the interviews that administrative involvement is lacking in the promotion of sustainability research in this university. Being the main actors of academic research, faculty, such as P4, P6, P8, and P10, opine that if the university wants it in an efficient and effective manner, the involvement of top management is necessary.

It must be top-down. Professors are busy, professors are lazy, and professors refuse or react without reason. So, it must be top-down. Top-down is when the university wants you to do it. And if you don’t do it, you’re going to lose something. It must be top-down, but exactly what we are doing now is not in that manner (Excerpt from the interview of P4).

According to them, faculty, as human beings, try to secure a comfortable position. When they are given an option to include certain new things in their routine, they refuse to do so. Therefore, the faculty themselves feel that the president and vice president should be active in promoting sustainability so that the activity system of the faculty would become more productive. This means that a proper division of labor, in a top-down manner, is missing in the university’s activity system between the administration and faculty.

The top-down approach involves the organizational executives to formulate and implement plans, middle management to coordinate and internally manage the change, and non-managerial employees to play their role in embedding the change [128]. If the change is necessary, it is critical for the senior executives to initiate, favor, and drive it forward [129]. The top-down approach has achieved its importance for the organizations with regard to the popularity of transformational leadership theory [130], which prescribes that the involvement of higher executives can bring change in their organizations [128]. They can do so by realizing a need for change, crafting a vision, and implementing the change to the whole organization [131]. This kind of change is brought about by the transformational leaders by means of inspiration, support, and empowerment of their employees and by developing a hierarchy that is supportive to modify the existing culture [132,133]. Therefore, the involvement of leadership is required to engage people in taking actions and working around a shared vision [25] because leadership with a purpose along with a governance process assures engagement and brings about innovation towards a sustained change [134]. The academic mission is key for engaging the university with sustainability-related work. However, the university administration is currently focusing on improving the quality of existing common indicators of university ranking proposed by the ranking agencies [135]. They have not yet conceptualized the inclusion of the emerging sustainability indicators as part of their organizational policies, which is hampering the administrative involvement in internalizing sustainability in its organizational activities. Despite having the power and legitimacy to do so, the lack of perceived urgency is hampering administrative involvement in terms of conceiving and setting a unified direction to be followed by faculty and other relevant stakeholders and to internalize the sustainability in their academic and professional endeavors.

5.6. Conflict between the Government’s Policy and Sustainability

Government is an important actor associated with the faculty’s research activity system. The government sets certain preferences for the country, and through its ministries, it provides funding to foster research and innovation in the areas of preference. The policies and activities of government are some of the determinants of setting research direction for the researchers in the country. The faculty in the domains of energy and environment, including P2, P3, and P4, point out that the government did not care much about the emission reduction and climate change issues (contradiction #9 on object, in Figure 2). Moreover, it focuses more on economic goals than on sustainability goals and the future of mankind.

Our government is not taking sustainability seriously. They are burning coal to generate electricity and they are polluting our environment. They think that if you try to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, it will reduce economic growth. The government will always be hesitating that if I push too hard, it’s going to affect the economic goals of the nation. And next time, I will lose the election. (Excerpt from the interview of P2).

Furthermore, the faculty feel that the government’s emphasis on certain sources of energy, such as fossil fuel and renewable energy, is not a viable strategy. Since fossil fuel is not environmentally friendly, and renewable sources are unstable and non-reliable sources of energy, the government should set its direction to adopt sustainable alternatives as sources of energy. This direction would cascade down to open venues for researchers to offer alternative yet sustainable and innovative solutions thereof. Accordingly, researchers have been focusing on the use of nuclear energy as an effective source of clean energy but claim that the government is planning to phase out nuclear energy. It is evident that there is a disbalance in the government’s objectives toward a better future for the country, i.e., they care more about economic growth rather than a sustainable future for mankind. Thus, this study finds that there is a primary contradiction in the object of the government’s activity system.

Although economic growth, clean energy, and climate action are the components of 17 SDGs proposed by the United Nations in 2015, all the countries are expected to keep an optimized balance in formulating and pursuing their strategies to achieve these goals. However, faculty have reported that the government focuses much more on economic growth (SDG 8) than on clean energy (SDG 7) and climate action (SDG 13) with a political intent to indicate a visible performance of their policies and strategies. Thus, the political intent in devising strategies is considered a major cause of disbalance or tension in the object of the government’s activity system towards sustainability.

In universities, the largest amount of their budget is based on ‘negotiated funding formulas,’ e.g., the size of staff and number of students, or performance-based funding approaches, and in this way, universities compete for research funding based on their outstanding research proposals to achieve a certain set of objectives [136]. However, these approaches vary across the countries [137]. HEIs are given a niche to organize research environments to produce and diffuse knowledge that would tangibly contribute to the economy, society, and environment [138]. These kind of research activities are generally supported by the government through provision of a certain amount of funding. However, there is a challenge for the government to make balanced decisions on how to optimally promote growth and development as well as simultaneously foster environmental protection and alleviate climate change [139]. Activities to promote economic development lead to emissions in turn, and at the same time, activities and efforts to lessen emissions, and the impacts of climate change, are costly [140]. In this scenario, it is difficult to pursue both economic development and environmental protection, as the economic development produces negative externalities and consumes and depreciates the resources that otherwise may be utilized for environmental protection [139]. However, research shows that economic development and environmental protection can simultaneously be pursued through certain approaches, such as smart growth [141,142], for example, the allocation of priority funding directed towards fostering compact communities. The faculty in this study report that the government is still focusing more on economic development than on environment and climate change. This approach affects the government’s support for the academic contribution in the area of environment and climate change. The government can optimize its policies via smart growth approaches. The government has power and legitimacy as per the stakeholders model of salience [71] to align its policies. However, the lack of perceived urgency from the government to put more efforts for environmental protection and mitigating climate change has been hindering the enhancement of knowledge creation on sustainability.

6. Discussions

The importance of the involvement of HEIs in supporting sustainability has been widely illuminated in the previous literature. Being the leaders in education, research, and innovation, universities are considered as cornerstone in the sustainable development through their strategies in terms of education and research [13,18]. In this way, an increasing number of universities are trying to align their research and activities with the concept of sustainability [19]. However, recent studies [23] report that sustainability-related research has not been systematically conducted in HEIs through administrative efforts. Therefore, by interviewing eleven faculty members at a research university, this study presents a way in which sustainability can be internalized in academic research and innovation. This study found tensions (contradictions) within, and between, the activity systems to delineate the causes that explain why only few researchers have been able to internalize sustainability in their research. This study identified the directions of reconfiguring service systems to enhance the internalization of sustainability in research at HEIs. From the study of practices and plans of faculty members (the main stakeholders of research and innovation activities at HEIs) in the internalization of sustainability in their scholarly research, we conclude the following propositions.

According to service science, anything is a potential resource that can be, in some way, used to realize value [143]. Service dominant logic recognizes two categories of resources i.e., operand resources that need some action to be taken upon to be valuable, and operant resources that have ability to act upon others to create value [40,42]. Although operand resources contribute to value co-creation, operant resources (e.g., knowledge, skills, competences, and organizational processes) are considered essential for the integration of resources for value co-creation [40,144]. In this way, faculty members at HEIs generally integrate operand resources (e.g., technological infrastructure and financial resources), and operant resources (e.g., their knowledge, skills, and expertise) to co-create value in terms of research and innovation. However, we have identified how faculty had limited resources such as technology and finances to undertake research projects on sustainability. They did not have proper access to the technology required to undertake sustainability-related research (contradiction #1 on tool). The faculty felt that due to limited access to the required technology, they could not produce viable solutions for sustainability-related issues. The acquisition of that technology is out of their affordability and to access the common technological facility provided by the university is also very expensive. Moreover, the faculty also faced financial constraints in conducting research on sustainability (contradiction #2 on tool) as their proposals on sustainability related work are seldom considered for approval by the funding agencies and authorities. In this situation, the faculty’s urgent and legitimate claims, but only low power to influence providers of financial and technological resources to work on sustainability make them dependent stakeholders [71], where they are dependent on university and other funding authorities and agencies to carry out their will. Consequently, there is a need for the faculty to curtail their dependency on direct funding for sustainability-related work by means of indirect sources of finances. For example, during our study, we found that some of the faculty with higher agency [145] and motivation [3] to work on sustainability used to re-deploy their slack resources from other promising projects in their fields of research to support their sustainability-related work. Therefore, it is recommended that the motivation of the employees should be enhanced, so that they would also strive to hunt other projects with sufficient resources and (re)integrate them to create value in terms of internalizing sustainability into their research. The conservation of resources theory [146] also ascribes that motivation directs humans to retain existing resources as well as to seek and pursue new resources. Based on these grounds, we propose Proposition 1 as follows.

Proposition 1.

Actors with high agency and motivation are more likely to integrate resources to create value in terms of internalizing sustainability.

Organizational inducements refer to the rewards and support provided by the organizations to the members to enhance their contribution to the organization [147]. One of the inducements an organization can provide is in monetary form in which the employees are paid when they perform their responsibilities [148]. The others are non-monetary inducements that are given in the form of training, career development, organizational support, etc. [149,150]. For instance, an organization may provide certain relevant training to its members, so that they are motivated and consequently contribute better to the organization because they recognize themselves as special members of that organization [151]. Students are important value co-creators at HEIs in terms of research and innovation. In this study, the faculty identified that sustainability-related courses have not yet been sufficiently included in their university’s curricula to develop students understanding about the concept of sustainability and to train them by imparting relevant skills (contradiction #3, between university’s tools and faculty’s objects), so that they would better align their academic activities and outcomes with sustainability. The university could redesign its curricula for graduate and undergraduate programs by including certain courses (even some seminar courses) on sustainability. Further, those courses could be made a compulsory requirement for awarding degrees. The university, especially in the division of curricula, could also offer some short-term certificate courses for interdisciplinary students, so that they would develop the necessary knowledge, skills, and expertise pertaining to sustainability. Moreover, the study found that there is a lack of mindset on sustainability among people at campus; thus, they don’t feel motivated to put their efforts into working for sustainability. Therefore, the completion of these degree courses and certificates (as inducements) would enhance the students’ self-confidence and motivation to internalize sustainability while the degrees and certificates (as educational credentials) would give a signal to the faculty, university, and their potential employers about the students’ ability and their competence to produce better performance outcomes, as suggested by signaling theory [78]. This study has also found that the university did not have any proper reward or incentives system in place to recognize scientific work on sustainability (contradiction #4 between the university’s tool and the faculty’s object). Consequently, the faculty felt it cumbersome to internalize the concept of sustainability into their research work and they preferred to remain with their respective domains of research. As design and execution of the reward systems in order to concede the employees’ accomplishments, or their achievements, have a predictable influence on their intrinsic motivation [2], the university could show some urgency [71] and reconfigure its service system to include monetary inducements, such as incentives, bonuses, cash awards etc., and non-monetary inducements such as periodic award competitions, promotion policies, etc., as tools to enhance the motivation of its employees to internalize sustainability in their research. Based on the above discussion, we conclude Proposition 2 as follows:

Proposition 2.

A university that provides more inducements to their organizational members are more likely to enhance their motivation to internalize sustainability.