Association between Internal Control and Sustainability: A Literature Review Based on the SOX Act Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

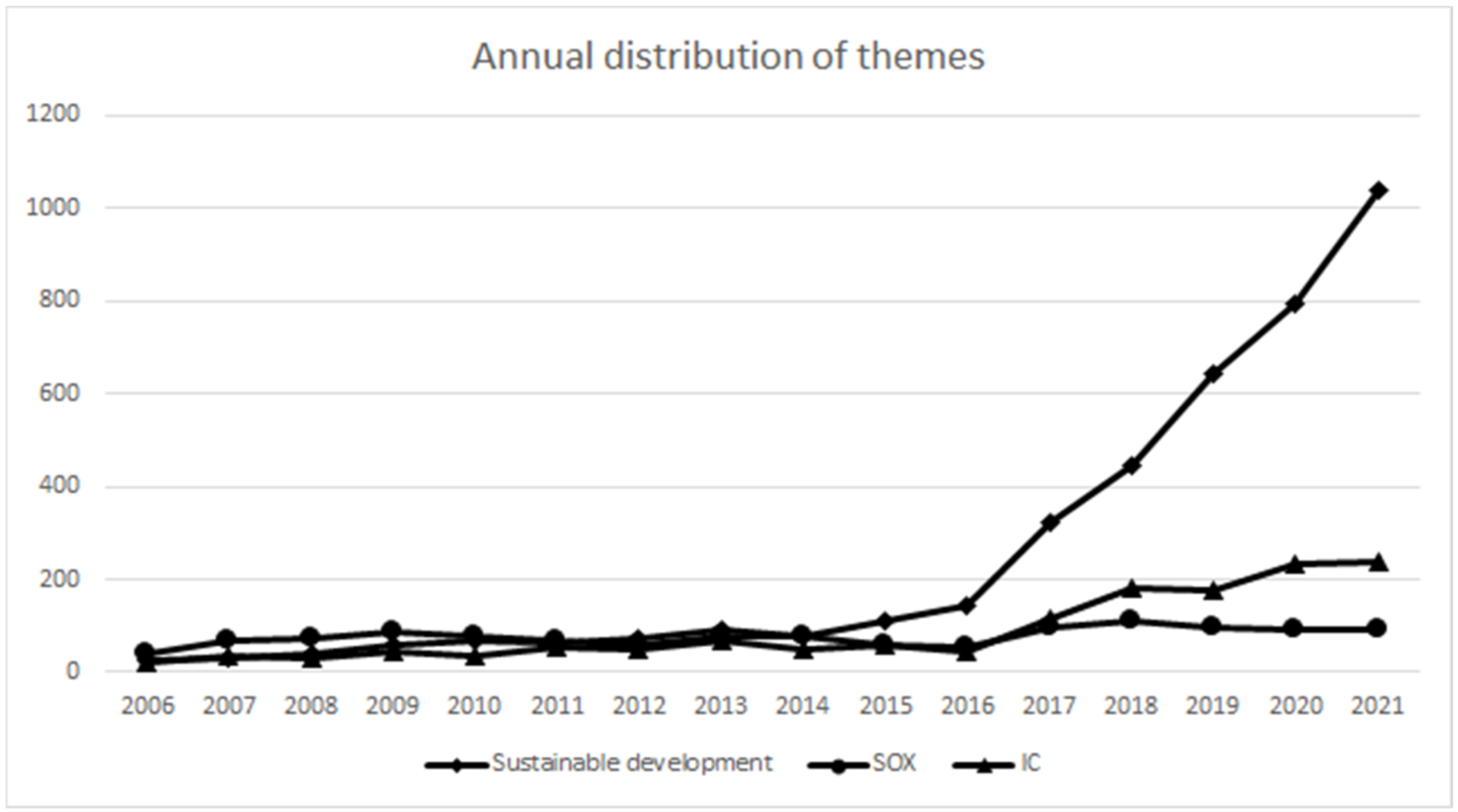

3. Results

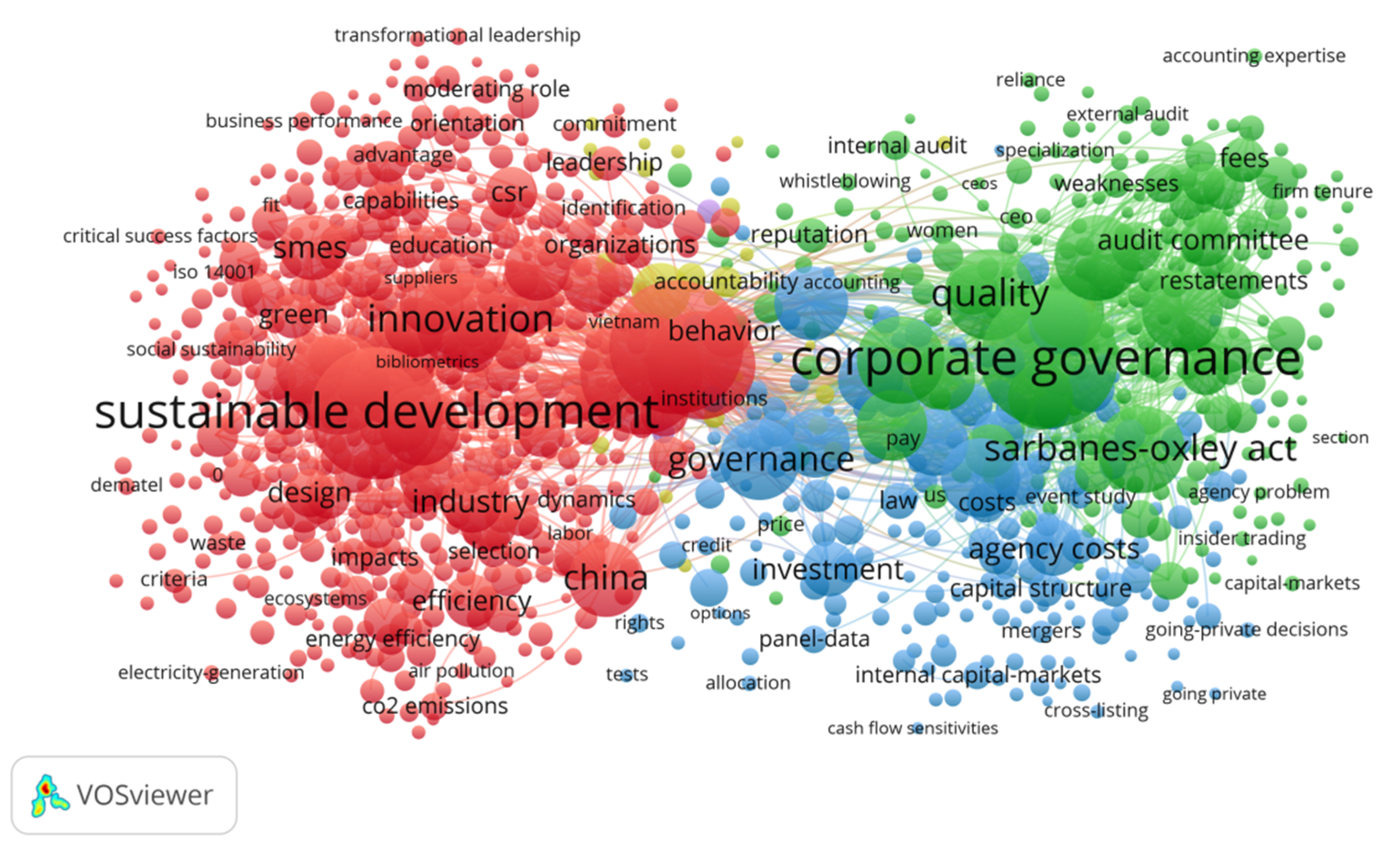

3.1. Determinants of Enterprise Sustainable Development

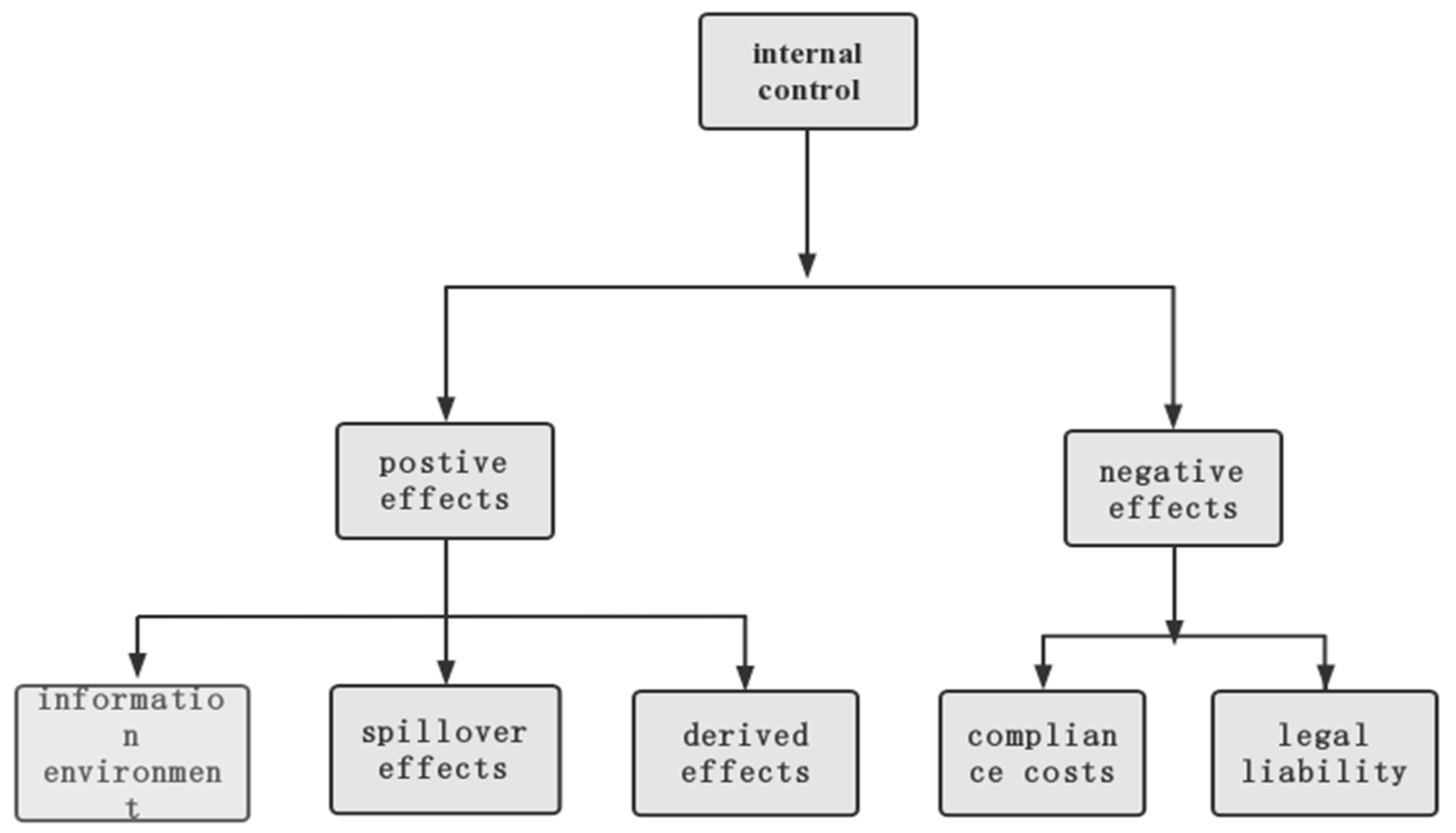

3.2. Economic Consequences of Internal Control in the SOX Act Framework

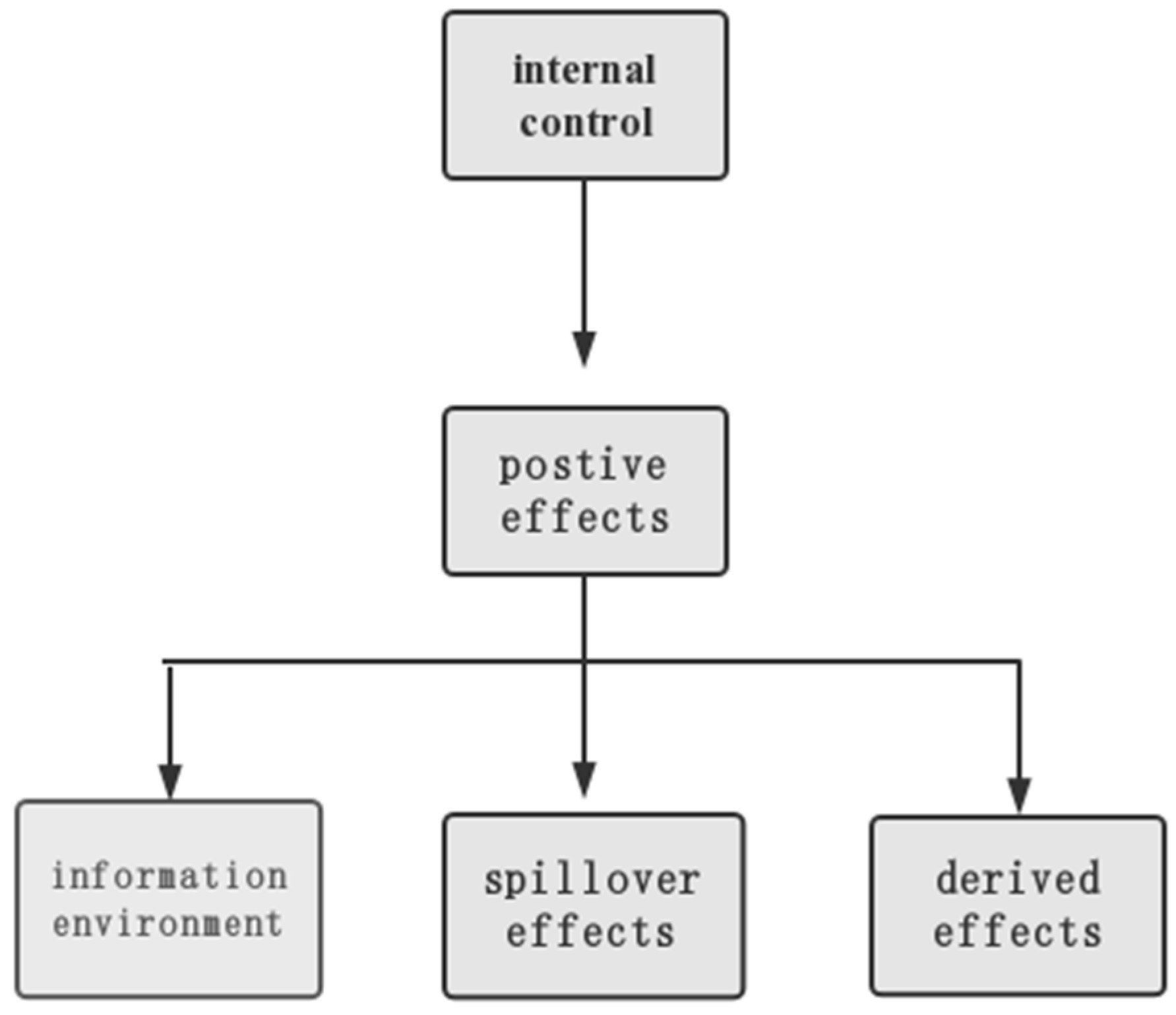

3.2.1. Positive Consequences

- (1)

- Financial information quality and information transparency

- (2)

- Positive evidence of the SOX Act derivation effects

- (3)

- Positive evidence of the SOX Act spillover effects

3.2.2. Negative Consequences

- (1)

- Negative evidence of the SOX Act and high compliance costs

- (2)

- Negative evidence of the SOX Act and legal liability

3.3. Analysis at Different Country Levels

3.3.1. The Impact of Internal Controls in the SOX Act Framework on the Sustainable Development of U.S. Enterprises

3.3.2. The Impact of Internal Control on the Sustainable Development of Chinese Enterprises under the SOX Act Framework

- Positive evidence of the SOX Act’s impact on the information environment

- 2.

- Positive evidence of SOX derivation effects

- 3.

- Positive evidence of SOX spillover effects

3.3.3. The Impact of Internal Control under the SOX Act Framework on the Sustainable Development of Enterprises in Other Countries

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suh, C.J.; Lee, I.T. An empirical study on the manufacturing firm’s strategic choice for sustainability in SMEs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Towards the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.H. Internal control: Nature and structure. Account. Res. 2009, 12, 70–75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, T.; Zuo, Y.; Sun, F.; Lee, J.Y. Customer concentration, economic policy uncertainty, and sustainable enterprise innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, M.E.; Melero-Polo, I.; Vázquez-Carrasco, R.; Cambra-Fierro, J. Sustainability and business outcomes in the context of SMEs: Comparing family firms vs. non-family firms. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Bu, H.; Sun, H. The Impact of On-the-Job Consumption on the Sustainable Development of Enterprises. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, M.A.; Lin, J.; Rehman, R.U.; Ahmad, M.I.; Ali, R. Does capital structure mediate the link between CEO characteristics and firm performance? Manag. Decis. 2019, 7, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S.; Zardini, A. Is sustainability a competitive advantage for small businesses? An empirical analysis of possible mediators in the sustainability–financial performance relationship. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.S. Social responsibility, green accounting implementation, and sustainable development of heavy polluters. Financ. Account. Newsl. 2019, 815, 12–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Cheng, Y.; Su, X. Research on the sustainability of the enterprise business ecosystem from the perspective of boundary: The china case. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masocha, R.; Fatoki, O. The impact of coercive pressures on sustainability practices of small businesses in South Africa. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masocha, R.; Fatoki, O. Social Sustainability Practices on Small Businesses in Developing Economies: A Case of South Africa. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degong, M.; Ullah, F.; Khattak, M.S.; Anwar, M. Do international capabilities and resources configure a firm’s sustainable competitive performance? Research within Pakistani SMEs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Weng, Y.C.; Wang, F. The effect of the internal control regulation on reporting quality in China. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2021, 21, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, J.H.; Shepardson, M.L. Do SOX 404 Control Audits and Management Assessments Improve Overall Internal Control System Quality? Account. Rev. 2016, 91, 1513–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.M.; Liu, C.L.; Chen, S.S. Internal control quality and investment efficiency. Account. Horiz. 2020, 34, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, D.; Zhang, J.H.; Zhou, H. Internal controls, risk management, and cash holdings. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 64, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenard, M.; Petruska, K.; Pervaiz, A.; Bing, Y. Internal control weaknesses and evidence of real activities manipulation. Adv. Account. Inc. Adv. Int. Account. 2016, 33, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.M. Tax avoidance and the implications of weak internal controls. Contemp. Account. Res. 2016, 33, 449–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, G.; Li, Y.; Li, T.; Zheng, S.X. Internal control weakness, investment, and firm valuation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2018, 25, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, B.; Lian, Q.; Rupley, K.; Zhao, J. Industry contagion effects of internal control material weakness disclosures. Adv. Account. 2016, 34, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, P. The effect of SOX Section 404: Costs, earnings quality, and stock prices. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1163–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuz, C.; Triantis, A.; Wang, T.Y. Why do firms go dark? Causes and economic consequences of voluntary sec deregistrations. J. Account. Econ. 2008, 45, 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Dey, A.; Lys, T.Z. Corporate governance reform and executive incentives: Implications for investments and risk-taking. Contemp. Account. Res. 2013, 30, 1296–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargeron, L.L.; Lehn, K.M.; Zutter, C.J. Sarbanes-Oxley and corporate risk-taking. J. Account. Econ. 2010, 49, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, O.; Kashchena, N.; Staverska, T.O.; Chmil, H. Sustainable development of enterprises with the digitalization of economic management. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 2370–2378. [Google Scholar]

- Choongo, P. A Longitudinal Study of the Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Performance in SMEs in Zambia. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoreaux, P.T. Does PCAOB inspection access improve audit quality? An examination of foreign firms listed in the United States. J. Account. Econ. 2016, 61, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFond, M.; Hung, M.; Carr, E.; Zhang, J. Was the Sarbanes–Oxley Act good news for corporate bondholders? Account. Horiz. 2011, 25, 465–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tong, P.; Zhao, C.; Wang, H. Research on the survival and sustainable development of small and medium-sized enterprises in China under the background of a low-carbon economy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, A. A bibliometric and content analysis of sustainable development in small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarango-Lalangui, P.; Álvarez-García, J.; Río-Rama, D.; De la Cruz, M. Sustainable practices in small and medium-sized enterprises in Ecuador. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantalo, C.; Caroli, M.G.; Vanevenhoven, J. Corporate social responsibility and SME’s competitiveness. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2012, 58, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, A.; Bititci, U. Change process: A key enabler for building resilient SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5601–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duygulu, E.; Ozeren, E.; Işıldar, P.; Appolloni, A. The sustainable strategy for small and medium-sized enterprises: The relationship between mission statements and performance. Sustainability 2016, 8, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Pardo, R.J.; Bhamra, T.; Bhamra, R. Sustainable product-service systems in small and medium enterprises (SMEs): Opportunities in the leather manufacturing industry. Sustainability 2012, 4, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Byard, P.; Francis, M.; Fisher, R.; White, G.R. Profiling the resiliency and sustainability of UK manufacturing companies. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2016, 27, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombiak, E.; Marciniuk-Kluska, A. Green human resource management as a tool for the sustainable development of enterprises: Polish young company experience. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacob, P.; Wong, L.S.; Khor, S.C. An empirical investigation of green initiatives and environmental sustainability for manufacturing SMEs. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sajjad, N.; Wang, Q.; Muhammad Ali, A.; Khaqan, Z.; Amina, S. Influence of transformational leadership on employees’ innovative work behavior in sustainable organizations: Test mediation and moderation processes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Avery, G. Sustainable leadership practices driving financial performance: Empirical evidence from Thai SMEs. Sustainability 2016, 8, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, A.A.; Brem, A. Sustainability in SMEs: Top management teams’ behavioral integration as a source of innovativeness. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Chang, A.Y.; Luo, W. Identifying key performance factors for sustainable development of SMEs–integrating QFD and fuzzy MADM methods. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Farracho, M.; Bosworth, R.; Kemp, R.P.M. The front-end of eco-innovation for eco-innovative small and medium-sized companies. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2014, 31, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przychodzen, J.; Przychodzen, W. Relationships between Eco-Innovation and Financial Performance—Evidence from Publicly Traded Companies in Poland and Hungary. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 90, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halila, F.; Tell, J. Creating synergies between SMEs and universities for ISO 14001 certification. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajan, M.P.; Shalij, P.R.; Ramesh, A.; Augustine, P.B.; Steenhuis, H.J. Lean manufacturing practices in Indian manufacturing SMEs and their effect on sustainability performance. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2017, 28, 772–793. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, C.; Chung, Y.; Chun, D.; Seo, H. Exploring the impact of complementary assets on the environmental performance in manufacturing SMEs. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7412–7432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.; Luca, C.; Sarno, D. The Influence of Cognitive Dimensions on the Consumer-SME Relationship: A Sustainability-Oriented View. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.M.; Kiel, D.; Voigt, K.I. What drives the implementation of Industry 4.0? The role of opportunities and challenges in the context of sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upstill-Goddard, J.; Glass, J.; Dainty, A.; Nicholson, I. Developing a sustainability assessment tool to aid organizational learning in construction SMEs. Assoc. Res. Constr. Manag. 2015, 9, 457–466. [Google Scholar]

- Agan, Y.; Acar, M.F.; Borodin, A. Drivers of environmental processes and their impact on performance: A study of Turkish SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 51, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crals, E.; Vereeck, L. The affordability of sustainable entrepreneurship certification for SMEs. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2005, 12, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, K.; Hay, D.; Khlif, H. Internal control in accounting research: A review. J. Account. Lit. 2018, 42, 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, J.; Gao, Y.; Cheng, Q. The Analysts’ Information Environment Changes Following the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the Global Settlement; Working paper; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, B.W.; Krishnan, J.; Li, D. Auditor reporting under Section 404: The association between the internal control and going concern audit opinions. Contemp. Account. Res. Forthcom. 2013, 30, 970–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.T.; Ge, W.; McVay, S. Accruals quality and internal control over financial reporting. Account. Rev. 2007, 82, 1141–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamuro, J.; Beatty, A. How Does Internal Control Regulation Affect Financial Reporting? J. Account. Econ. 2010, 49, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, B.W.; Li, D. Internal controls and conditional conservatism. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 975–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Li, C.; McVay, S. Internal control and management guidance. J. Account. Econ. 2009, 48, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arping, S.; Sautner, Z. Did sox section 404 make firms less opaque? evidence from cross-listed firms. Contemp. Account. Res. 2013, 30, 1133–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Strong, N.; Zhu, Z. Did fair regulation disclosure, SOX, and other analyst regulations reduce security mispricing? J. Account. Res. 2014, 52, 733–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.A.; Wilford, A.L. An analysis of multiple consecutive years of material weaknesses in internal control. Account. Rev. 2012, 87, 2027–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Increased disclosure requirements and corporate governance decisions: Evidence from chief financial officers in the pre-and-post Sarbanes-Oxley periods. J. Account. Res. 2010, 48, 885–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Li, C.; McVay, S.; Ashbaugh-Skaife, H. Does ineffective internal control over financial reporting affect a firm’s operations? Evidence from firms’ inventory management. Account. Rev. 2015, 90, 529–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donelson, D.C.; Ege, M.S.; McInnis, J.M. Internal control weaknesses and financial reporting fraud. Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2017, 36, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Chung, K. The effect of commercial banks’ internal control weaknesses and loan loss reserves and provisions. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2016, 12, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Dhaliwal, D.; Zhang, Y. Does investment efficiency improve after disclosing material weaknesses in internal control over financial reporting? J. Account. Econ. 2013, 56, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggi, B.; Mitra, S.; Hossain, M. Earnings quality: Internal control weaknesses and industry-specialist audits. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2015, 45, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowdell, D.; Herda, D.; Notbohm, A. Do management reports on internal control over financial reporting improve financial reporting? Res. Account. Regul. 2014, 26, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Jaggi, B.; Hossain, M. Internal control weaknesses and accounting conservatism: Evidence from the post–Sarbanes–Oxley period. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2013, 28, 152–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. Internal control weakness disclosure and firm investment. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2016, 31, 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, M.; Ziebart, D.A. Did Japanese-SOX have an impact on earnings management and earnings quality? Manag. Audit. J. 2015, 30, 482–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thuneibat, A.; Al-Rehaily, A.; Basodan, Y. The impact of internal control requirements on the profitability of Saudi shareholding companies. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2015, 25, 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Richardson, G.; Salterio, S. Direct and indirect effects of internal control weaknesses on accrual quality: Evidence from a unique Canadian regulatory setting. Contemp. Account. Res. 2011, 28, 675–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myllymäki, E.R. The association between Section 404 material weaknesses and financial reporting quality is persistent. Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2014, 33, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallemore, J.; Labro, E. The importance of the internal information environment for tax avoidance. J. Account. Econ. 2015, 60, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.F.; Chang, M.L. Do auditor-provided tax services improve the relation between tax-related internal control and book-tax differences? Asia-Pac. J. Account. Econ. 2016, 23, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvinen, T.; Myllymäki, E. Real earnings management before and after reporting SOX 404 material weaknesses. Account. Horiz. 2016, 30, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevzner, M.; Gaynor, G. The impact of internal control weaknesses on firms’ cash policies. Int. J. Account. Audit. Perform. Eval. 2016, 12, 396–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.D.; Lu, W.; Qu, W. Internal control weakness and accounting conservatism in China. Manag. Audit. J. 2016, 31, 688–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Dey, A.; Lys, T.Z. Real and accrual-based earnings management in the pre-and post-Sarbanes-Oxley periods. Account. Rev. 2008, 83, 757–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, A.; Lin, J.; Pinsker, R. Do material weaknesses in information technology-related internal controls affect firms’ 8-K filing timeliness and compliance? Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2016, 22, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsif, V.; Raghunandan, K.; Rama, D.V. Internal control reporting and audit report lag: Further evidence. Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2012, 31, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunandan, K.; Rama, D.V. SOX Section 404 material weakness disclosures and audit fees. Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2006, 25, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, C.E.; Wilkins, M.S. Evidence on the audit risk model: Do auditors increase audit fees due to internal control deficiencies? Contemp. Account. Res. 2008, 25, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.C.; Pott, C.; Wömpener, A. Internal control and risk management regulation on earnings quality: Evidence from Germany. J. Account. Public Policy 2014, 33, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneish, M.D.; Billings, M.B.; Hodder, L.D. Internal control weaknesses and information uncertainty. Account. Rev. 2008, 83, 665–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbaugh-Skaife, H.; Collins, D.W.; Kinney, W.R., Jr.; LaFond, R. The effect of SOX internal control deficiencies on firm risk and cost of equity. J. Account. Res. 2009, 47, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.M.; Moerman, R.W. Financial reporting quality on debt contracting: Evidence from internal control weakness reports. J. Account. Res. 2011, 49, 97–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.; Church, B.K. The effect of auditors’ internal control opinions on loan decisions. J. Account. Public Policy 2008, 27, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.B.; Song, B.Y.; Zhang, L. Internal control weakness and bank loan contracting: Evidence from SOX Section 404 disclosures. Account. Rev. 2011, 86, 1157–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, E.; Hayes, R.M.; Wang, X. The Sarbanes–Oxley Act and firms’ going-private decisions. J. Account. Econ. 2007, 44, 116–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Wu, J.S.; Zimmerman, J. Unintended consequences of granting small firms exemptions from securities regulation: Evidence from the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. J. Account. Res. 2009, 47, 459–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J. The goals and promise of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. J. Econ. Perspect. 2007, 21, 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmstrom, B.; Kaplan, S. US corporate governance: What’s right and what’s wrong? J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2003, 15, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroszner, R. The economics of corporate governance reform. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2004, 16, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, R.; Gao, X.; Jia, Y. Internal control and internal capital allocation: Evidence from internal capital markets of multi-segment firms. Rev. Account. Stud. 2017, 22, 251–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettredge, M.L.; Li, C.; Sun, L. The impact of SOX Section 404 internal control quality assessment on audit delay in the SOX era. Audit. J. Pract. Theory 2006, 25, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintoki, M.B. Corporate boards and regulation: The effect of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act and the exchange listing requirements on firm value. J. Corp. Financ. 2007, 13, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. The Sarbanes–Oxley act and cross-listed foreign private issuers. J. Account. Econ. 2014, 58, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.C.; Sun, H.L.; Tang, A.P. Effect of SEC enforcement actions on forced turnover of executives: Evidence associated with SOX provisions. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2021, 76, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, I.X. Economic consequences of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002. J. Account. Econ. 2007, 44, 74–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvak, K. The effect of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act on non-US companies cross-listed in the US. J. Corp. Financ. 2007, 13, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, B.; Matson, D. Strategies of resistance to internal control regulation. Account. Organ. Soc. 2008, 33, 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassar, G.; Gerakos, J. Determinants of hedge fund internal controls and fees. Account. Rev. 2010, 85, 1887–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Liu, J.; Xu, N. Internal control, property rights, and executive compensation performance sensitivity. Account. Res. 2011, 10, 42–48. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chi, G.; Zhu, J.; Wang, L. A study on the integrated management of hidden corruption in executives’ joint prevention and control—An empirical test based on the relationship between internal control and performance appraisal system. J. Manag. 2022, 3, 122–143. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, N.Y.; Anderson, A.; Bonaparte, I.; Tang, A.P. Internal control material weakness and real earnings management. In Parables, Myths and Risks; Emerald Publishing Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 2017; Volume 20, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X.; Kaplan, S.E.; Lu, W.; Qu, W. The role of voluntary internal control reporting in earnings quality: Evidence from China. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2020, 16, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.G.; Chen, H.W. Internal control, institutional environment, and stock liquidity. Econ. Res. Suppl. 2013, 1, 132–143. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Xu, N.; Shi, S.H. The “double-edged sword” role of internal control: A study of budget execution and budget slack. Manag. World 2015, 12, 130–145. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.F.; Lin, B.; Song, L. The role of internal control in corporate investment: Efficiency promoter or inhibitor? Manag. World 2011, 2, 81–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.G.; Zheng, J.; Wang, S.Z. Internal control and corporate value: An empirical analysis of A-shares in Shanghai and Shenzhen. Financ. Econ. Res. 2007, 4, 132–143. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Huang, W.; Chan, K.C.; Chen, T. Social trust and internal control extensiveness: Evidence from China. J. Account. Public Policy 2022, 41, 106940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.J.; Matkin, D.S.; Marlowe, J. Internal control deficiencies and municipal borrowing costs. Public Budg. Financ. 2017, 37, 88–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.F.; Lee, G.; Qin, B. Whistleblowing allegations, audit fees, and internal control deficiencies. Contemp. Account. Res. 2021, 38, 32–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enomoto, M.; Yamaguchi, T. Empirical evidence from Japan is evidence of discontinuities in earnings and earnings change distributions after j-sox implementation. J. Account. Public Policy 2017, 36, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizaki, R.; Takano, Y.; Takeda, F. Information content of internal control weaknesses: The evidence from Japan. Int. J. Account. 2014, 49, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st-century business john Elkington. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golusin, M.; Ivanović, O.M. Definition, characteristics, and state of the indicators of sustainable development in countries of Southeastern Europe. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2009, 130, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viesi, D.; Pozzar, F.; Federici, A.; Crema, L.; Mahbub, M.S. Energy efficiency and sustainability assessment of about 500 small and medium-sized enterprises in Central Europe. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragija, M.; Vašiček, V.; Hladika, M. Internal Audit and Control Trends in the Public Sector of Transition Countries. In Proceedings of the 5th International Scientific Conference “Entrepreneurship and Macroeconomic Management: Reflections on the World in Turmoil”, Pula, Croatia, 24–26 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Malesios, C.; Skouloudis, A.; Dey, P.K.; Abdelaziz, F.B.; Kantartzis, A.; Evangelinos, K. Impact of small-and medium-sized enterprises sustainability practices and performance on economic growth from a managerial perspective: Modeling considerations and empirical analysis results. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 960–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Influencing Factor | Sample | Research Method | Country | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Enterprise Characteristics (nine studies) | |||||

| [5] | Ownership | 1000 | empirical study 2016 | US | Family businesses pay more attention to enterprise reputation, brand image, and other factors that affect the long-term development of enterprises. |

| [32] | Contact trade | 9843 | research study | Ecuador | To achieve the sustainable development of enterprises, the upstream and downstream enterprises must form a more consistent value standard. |

| [33] | Operating age | 1200 | empirical study 2007–2011 | Italy | The longer the business time frame, the more enterprises will achieve long-term development by actively fulfilling social responsibility. |

| [34] | Organization resilience | 232 | research study | US | Resilience is seen as a key organizational capacity for sustainable development. |

| [35] | Enterprise statement and strategy | 3034 | research study | Turkey | A clear corporate mission is conducive to achieving organizational goals, including sustainable development. |

| [36] | Information and communication technology | 16 | research study | Columbia | Information and communication technologies for product and service design increase opportunities for sustainable enterprise development. |

| [37] | Advanced manufacturing technology | 72 | empirical study 2009–2012 | UK | Advanced technologies in product and service design increase opportunities for sustainable development. |

| [38] | Human resource management | 150 | research study | Poland | Green human resource management is of positive significance to the sustainable development of organizations. |

| [4] | customer concentration | 13,437 | empirical study 2009–2017 | China | There is a significant inverted-U-shaped relationship between customer concentration and sustainable enterprise innovations. |

| Panel B: Manager Characteristics (seven studies) | |||||

| [39] | Managerial attitudes | 260 | research study | Malaysia | The positive attitudes of business managers towards green initiatives makes environmental sustainability a solid competitive tool for development. |

| [40] | Transformational leadership | 281 | research study | China | Transformational leaders achieve sustainable development by promoting their subordinates’ innovative work behaviors. |

| [41] | Sustainable leadership practice | 439 | research study | Thailand | Sustainable Leadership (SL) practices play an important role in corporate financial performance. |

| [42] | Top management team with behavior integration | 40 | research study | Iran | Behaviorally integrated top management teams promote interaction among professionals to form core competencies. |

| [12] | Organizational and entrepreneurial resilience | 222 | research study | South Africa | Improving organizational and entrepreneurial resilience contributes to building positive and sustainable performance relationships. |

| [7] | Managerial power | 179 | empirical study 2009–2015 | Pakistan | Managerial power enables managers to take actions in favor of the enterprise, thereby providing impetus for its development. |

| [6] | On-the-Job Consumption | 19,021 | empirical study 2008–2019 | China | Reasonable and excessive on-the-job consumption has positive and inhibitory effects, respectively, on the sustainable development of enterprises. |

| Panel C: Social Responsiveness (four studies) | |||||

| [8] | Social performance | 348 | empirical study 2015 | Italy | The sustainable development of enterprises depends largely on the enterprise’s views on national sustainable development strategies and their strengths. |

| [27] | Community responsibility | 153 | research study | Zambia | Corporate social responsibility has a positive impact on sustainable performance. |

| [43] | Social problem | — | normative study | the Netherlands | Improving the sustainability of SMEs in manufacturing requires a combination of social, environmental, and commercial issues. |

| [9] | Community responsibility | 15,094 | empirical study 2010–2017 | China | The good performance of corporate social responsibility can provide key resources for the strategy of enterprises and help the harmonious development of enterprises. |

| Panel D: Environmental Responsiveness (six studies) | |||||

| [44] | Eco-innovation | 42 | research study | the Netherlands | Ecological innovation capability may become a new source of competitive advantage for sustainable development. |

| [45] | Eco-innovation | 439 | empirical study 2006–2013 | Poland and Hungary | Ecological innovators have higher returns on assets and rights, lower retained earnings, a larger scale than other enterprises, and more free cash flow. |

| [11] | Environmental policy | 222 | research study 2017 | South Africa | Mandatory isomorphic pressures have a significant impact on all three dimensions of sustainable development, namely, economy, environment, and society. |

| [46] | Environmental management system | 9 | action research 1999–2004 | Sweden | Enterprises can use learning networks to overcome obstacles to the implementation of environmental management systems to achieve sustainable development. |

| [47] | Green innovation | 252 | research study | India | The adoption of green innovations is driven by economic and institutional pressures that create value for their social sustainability. |

| [10] | Business Ecosystem | — | case study | China | How to create a good business ecosystem and sustainable development is the main problem faced by enterprises. |

| Panel E: External Effect (five studies) | |||||

| [48] | Market circumstances | 3497 | empirical study 2007–2009 | South Korea | An effective market environment is conducive to the sustainable development of enterprises. |

| [11] | Regulatory pressure | 238 | research study | South Africa | Mandatory isomorphic pressures from governments, environmental pressure groups, and other stakeholders have a profound impact on enterprise sustainability. |

| [13] | Internationalization level | 304 | research study | Pakistan | International finance, international technology, international experience, and international networks have a positive impact on the sustainable competitive performance of enterprises. |

| [49] | Market conditions | 175 | research study | Italy | The customer’s cognition dimension of enterprise sustainability practice has a significant influence on the economic performance of SMEs. |

| [50] | Changes in the external environment | 476 | empirical study 2017 | Germany | Opportunities and challenges are closely related to the sustainable development of enterprises. |

| Authors | Association(s) Examined | Sample | Period | Country | Main Findings | Effect of IC on Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Internal Control and Financial Information Quality (ten studies) | ||||||

| [55] | Sarbanes–Oxley Act, GS and analysts’ information environment | 6590 | 1997–2006 | Columbia | SOX and the concurrent analyst regulations are associated with a temporary increase in the quality of common information. | Positive |

| [56] | Internal control and growing concern for audit opinions | 39,749 | 2004–2009 | Canada | Enterprises with serious internal control deficiencies face greater uncertainty. | Positive |

| [57] | Internal control and accrual quality | 705 | 2002–2005 | US | Internal control can improve the accrual quality of enterprises. | Positive |

| [58] | Internal control and financial reporting | 16,191 | 1986–1992 1995–2001 | US | Internal control can improve the quality of financial reporting. | Positive |

| [59] | Internal controls and conditional conservatism | 1098 | 2000–2001 2003–2005 | US | Internal control can improve robustness. | Positive |

| [60] | Internal control and management forecasts | 11,531 | 2004–2006 | US | Better internal controls are associated with more accurate management forecasts. | Positive |

| [61] | SOX Section 404 and corporate transparency | 1923 | 2001–2007 | EU-15 | The SOX Act helps to reduce information opacity. | Positive |

| [62] | Analyst regulations and capital market information environment | 459,546 | 1983–2011 | US | The implementation of SOX improves analyst precision and reduces enterprise information opacity. | Positive |

| [15] | Forced internal control and information quality | 213,072 | 2001–2007 | US | SOX-404-forced internal control audit improves the quality of accounting information. | Positive |

| [14] | Internal control regulation and reporting quality | 14,028 | 2008–2017 | China | C-SOX has a positive effect on reporting quality and triggers no side effects, harming firms’ long-term value. | Positive |

| Panel B: Internal Control and Governance Decisions (22 studies) | ||||||

| [63] | Major defects of internal control and cost of equity | 24,806 | 2004–2009 | US | Significant defects in internal control have a negative impact on the cost of equity. | Positive |

| [64] | Internal control disclosure requirements and CFO | 27,797 | 1997–2006 | US | Mandatory internal control disclosure under SOX can effectively judge executive governance decisions. | Positive |

| [65] | IC quality over inventory and firms’ inventory management | 8953 | 2004–2009 | US | Enterprises with high-quality internal controls have more inventory management. | Positive |

| [66] | IC weakness and corporate fraud | 14,093 | 2005–2010 | US | There is a strong positive association between material IC weakness and future fraud revelation. | Positive |

| [67] | IC weakness disclosures and loan reserves and provisions in the banking sector | 8167 | 2002–2013 | US | Loan reserves and provisions are higher in years of IC weakness disclosures. | Positive |

| [68] | Disclosure of IC weakness and investment efficiency | 5544 | 2004–2007 | US | After SOX IC weakness disclosures, enterprises’ investment efficiency improves significantly. | Negative |

| [69] | Internal control weaknesses and industry-specialist audits | 7172 | 2004–2008 | US | Earnings quality of IC weakness enterprises audited by Big 4 industry specialists is higher than those audited by Big 4 nonspecialists. | Positive |

| [70] | Management’s IC reports and reporting quality proxied by discretionary accruals | 2339 | 2004–2010 | US | Management reports on IC quality improve financial reporting quality even in the absence of attestation. | Positive |

| [71] | IC weakness and accounting conservatism | 3492 | 2004–2009 | US | ICW enterprises exhibit greater accounting conservatism in the post-SOX period than enterprises with effective internal controls (non-ICW). | Negative |

| [72] | Internal control weakness disclosure and firm investment | 16,555 | 2004–2012 | US | Enterprises that receive adverse auditor internal control opinions have significantly lower investments than enterprises that receive clean opinions. | Positive |

| [73] | IC weaknesses and earnings quality, and management | 60 | 2009–2010 | Japan | Accrual and real earnings management remain unchanged (increase) for enterprises not disclosing (disclosing) IC weaknesses following J-SOX. | Positive |

| [74] | Compliance with IC legislation on corporate profitability | 160 | 2011 | Saudi Arabia | Two components of the IC system (risk assessment and control of procedures) have a positive effect on corporate profitability. | Positive |

| [75] | IC weakness disclosures and discretionary accruals | 470 | 2006 | Canada | A positive and significant association exists between IC weakness disclosures and discretionary accruals. | Positive |

| [76] | IC weakness and misstatements in financial information | 5249 | 2005–2008 | US | IC weaknesses under SOX 404 are positively associated with misstatements in financial information. | Positive |

| [19] | Tax-related material IC weakness and firms’ corporate tax avoidance | 6696 | 2004–2009 | US | Tax-related internal controls represent an important underlying determinant of tax avoidance, with significant cash flow effects. | Positive |

| [77] | IC effectiveness and tax avoidance | 11,606 | 2004–2010 | US | Effective IC systems are negatively related to effective tax rates. | Positive |

| [78] | Auditor-provided tax services and the association between tax-related IC and book-tax differences | 3705 | 2005–2011 | US | Enterprises with significant defects in internal control have higher tax avoidance and earnings management activities. | Positive |

| [79] | Material IC weakness disclosures and real earnings management | 23,409 | 2004–2012 | US | Enterprises with material IC weaknesses engage in more manipulation of real activities. | Positive |

| [80] | IC weaknesses and firms’ greater savings of cash from internally generated cash flows | 10,214 | 2005–2010 | US | IC weaknesses are associated with stronger cash-to-cash-flow sensitivities and with a weaker impact of higher asset liquidity on stock liquidity. | Positive |

| [81] | IC weaknesses and accounting conservatism | 1059 | 2010–2011 | China | IC weaknesses have a negative effect on accounting conservatism. | Positive |

| [16] | IC quality and investment efficiency | 20,437 | 2004–2008 | China | ICOFRs are more likely to make inefficient investments. | Positive |

| [17] | Internal controls, risk management, and cash holdings | 19,792 | 2007–2015 | China | Internal controls help companies shape reasonable cash policies that lead to value creation. | Positive |

| Panel C: Internal Control and Earnings Manipulation (five studies) | ||||||

| [82] | Implementation of SOX and earnings management | 8157 | 1987–2005 | US | The implementation of SOX reduces the earnings management of enterprises. | Positive |

| [18] | Material IC weakness disclosures and real earnings management | 7475 | 2004–2010 | US | There is a positive association between enterprises reporting IC weaknesses and real activities manipulation. | Positive |

| [19] | Internal control defects disclosed under SOX and corporate tax avoidance | 6696 | 2004–2009 | US | Significant reduction in corporate tax avoidance with significant tax-related internal control deficiencies. | Positive |

| [83] | Major defects of internal control and timeliness and compliance of company 8-K declaration | 118,808 | 2005–2010 | US | IC deficiencies reduce enterprises’ 8-K filing compliance and reporting timeliness. | Positive |

| [84] | Internal control reporting and audit report lags | 5678 | 2008–2009 | US | The improvement of SOX’s internal control quality can encourage enterprises to comply with laws and regulations. | Positive |

| Panel D: Internal Control and Other Stakeholders (ten studies) | ||||||

| [85] | SOX Section 404 material weakness disclosures and audit fees | 660 | 2003–2005 | US | Enterprises with internal control deficiencies are significantly more expensive than enterprises without internal control deficiencies. | Positive |

| [86] | Internal control defects and audit fees | 410 | 2003–2004 | US | Audit fees increase significantly after the disclosure of internal control deficiencies. | Positive |

| [87] | Permanently exempt from SOX 404 market reaction | 12,984 | 1994–2002 | Germany | The market reaction was negative when SOX 404 permanent immunity was granted to small enterprises. | Positive |

| [21] | Information disclosure and the same industry | 49,092 | 2005–2014 | US | Disclosures of corporate information with internal control deficiencies can lower shares in other enterprises in the same industry. | Positive |

| [20] | Internal control weakness, investment, and firm valuation | 1170 | 2004–2013 | US | Enterprises that disclose internal control deficiencies have poor market performance and low investor evaluation. | Positive |

| [88] | Internal control weaknesses and information uncertainty | 330 | 2004 | US | SOX requirements for establishing and improving internal controls have a positive impact on small and medium investors. | Positive |

| [89] | SOX internal control deficiencies, risks, and equity costs | 1053 | 2003–2005 | US | Internal control defects lead to concerns on the part ofof minority shareholders about the enterprise’s risk and the protection of legitimate rights and interests. | Positive |

| [90] | Financial report quality and debt contract | 2231 | 2002–2008 | US | Defects in internal control cause creditors to distrust financial information. | Positive |

| [91] | Auditor’s internal control opinions and creditors | 111 | experimental study | US | Enterprises where creditors are willing to accept better internal controls. | Positive |

| [92] | Internal control weakness and bank loan contracting | 1363 | 2005–2009 | US | Banks demand higher interest rates from borrowers when internal controls are inadequate. | Positive |

| Panel E: Internal Control and Compliance Costs (three studies) | ||||||

| [93] | Internal control system and operating costs | 470 going-private transactions | 1998–2005 | US | Strict compliance with the SOX Act and re-establishing internal sound controls could place a huge cost burden on enterprises. | Negative |

| [22] | SOX implementation and audit costs | 1499 | 2003–2004 | US | The increase in audit fees after SOX implementation is much larger than the increase in accrued quality. | Negative |

| [23] | SOX regulation and enterprise intent | 7249 | 1998–2004 | US | Enterprises choose to avoid SOX regulation by exiting secondary markets to reduce compliance costs. | Negative |

| Panel F: Internal Control and Social Response Cost (three studies) | ||||||

| [82] | SOX Act and corporate risk-taking | 14,604 | 1992–2006 | US | The SOX Act increases the cost of corporate responsibility and reduces risk appetite. | Negative |

| [25] | Sarbanes–Oxley and corporate risk-taking | 4342 | 1994–2006 | US, UK, Canada | SOX regulation significantly limits corporate risk-taking and innovation. | Negative |

| [94] | SOX liability avoidance and corporate behavior | 6946 | 1999–2001 2003–2005 | US | Enterprises obtain SOX exemptions by disclosing more bad news and reporting lower returns. | Negative |

| Country | Theoretical Framework and Scope | Scope of Responsibility of CPA | Scope of Practice | Empirical Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | A comprehensive internal control framework system under the COSO Committee | Audit and express an opinion on the effectiveness of management’s statement and audit and express an opinion on the effectiveness of internal control over financial reporting. | Internal Control over Financial Reporting | Positive and negative effects are combined [57,58] |

| China | Based on the comprehensive internal control framework system under the COSO Committee | An audit opinion on the effectiveness of the company’s internal control over overall reporting. | Comprehensive Internal Control | Positive impact [17,112] |

| Japan | Based on the comprehensive internal control framework system defined by the COSO Committee | The CPA is required to express an audit opinion only on the validity of the management’s statement, and is not permitted to express a separate audit opinion. | Internal Control over Financial Reporting | Positive impact [118,119] |

| United Kingdom | A comprehensive internal control framework system under the Turnbull Standard | Requires only a statement from the board of directors that it is responsible for the effectiveness of internal controls. | Internal Control over Financial Reporting | Positive Impact |

| Germany | Based on the comprehensive internal control framework system under the COSO standard | The audit opinion on the effectiveness of internal control must be provided to the supervisory board. | Comprehensive Internal Control | Positive effects [87] |

| Canada | A comprehensive internal control framework system under the integration of COSO and COCO standards | No CPA audit required. | Internal Control over Financial Reporting | Positive Impact |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, W.; Zhang, L.; Ge, C.; Chen, S. Association between Internal Control and Sustainability: A Literature Review Based on the SOX Act Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159706

Su W, Zhang L, Ge C, Chen S. Association between Internal Control and Sustainability: A Literature Review Based on the SOX Act Framework. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159706

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Wunhong, Liuzhen Zhang, Chao Ge, and Shuai Chen. 2022. "Association between Internal Control and Sustainability: A Literature Review Based on the SOX Act Framework" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159706

APA StyleSu, W., Zhang, L., Ge, C., & Chen, S. (2022). Association between Internal Control and Sustainability: A Literature Review Based on the SOX Act Framework. Sustainability, 14(15), 9706. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159706