Ibiza (Spain) World Heritage Site: Socio-Urban Processes in a Touristified Space

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. World Heritage Cities: Midway between Heritagization and Tourism Promotion

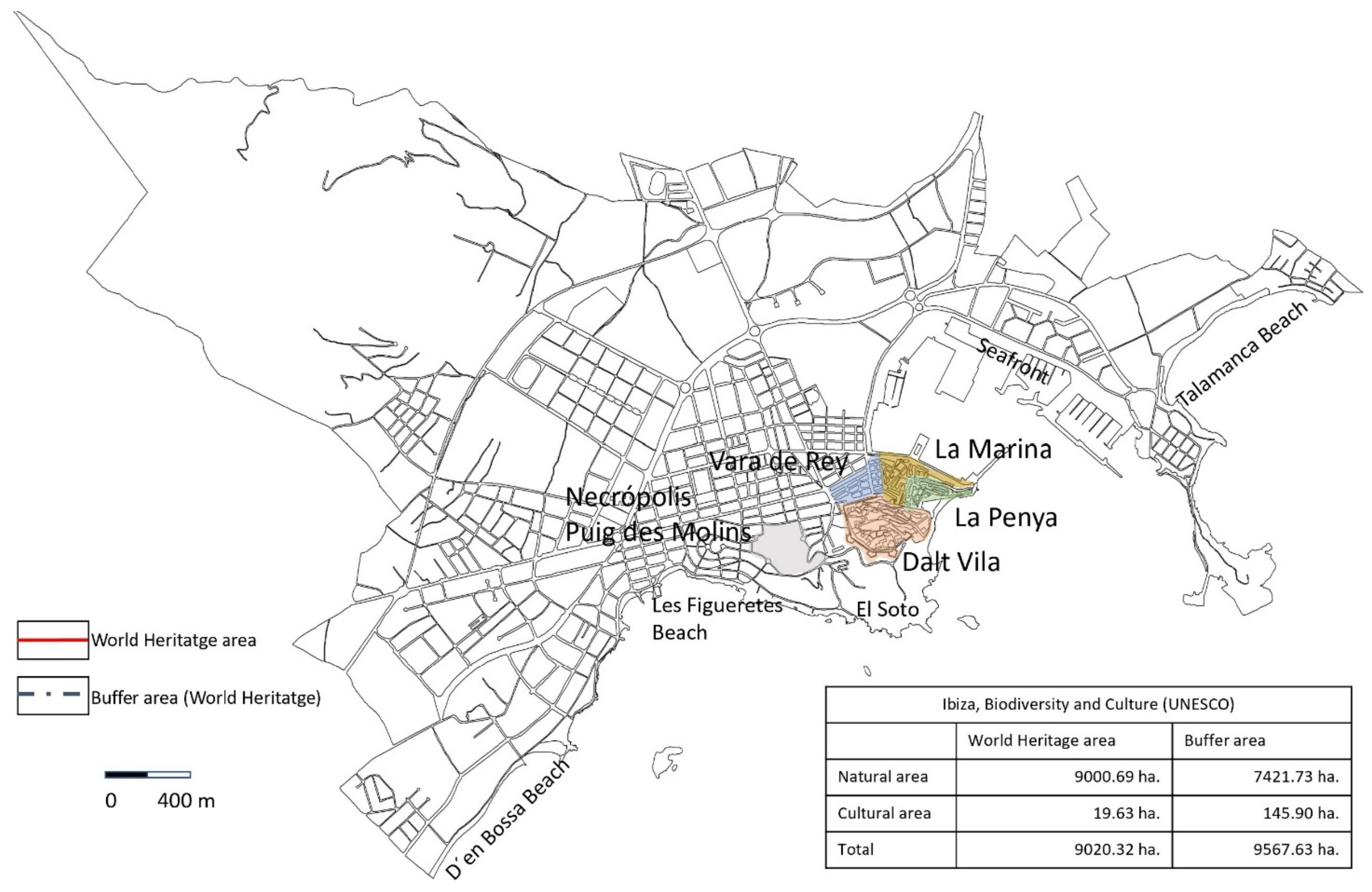

2.2. Dalt Vila’s Rich Heritage: A Strong Point in Ibiza’s Candidacy as a World Heritage Site

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Urbanization Process, Urban Structure, and Refurbishment Plans in Ibiza: A Summary

4.2. A Museumized City: Salient Interventions to Dalt Vila’s Heritage following the World Heritage Site Declaration

- To promote and fund the execution of work and the provision of services and infrastructure in general, together with suitable means of transport and communication networks relating to the World Heritage declaration.

- To promote the coordination of investment by public authorities into the necessary work or the provision of services and infrastructure.

- To promote cultural initiatives and projects aimed at the conservation of historical heritage.

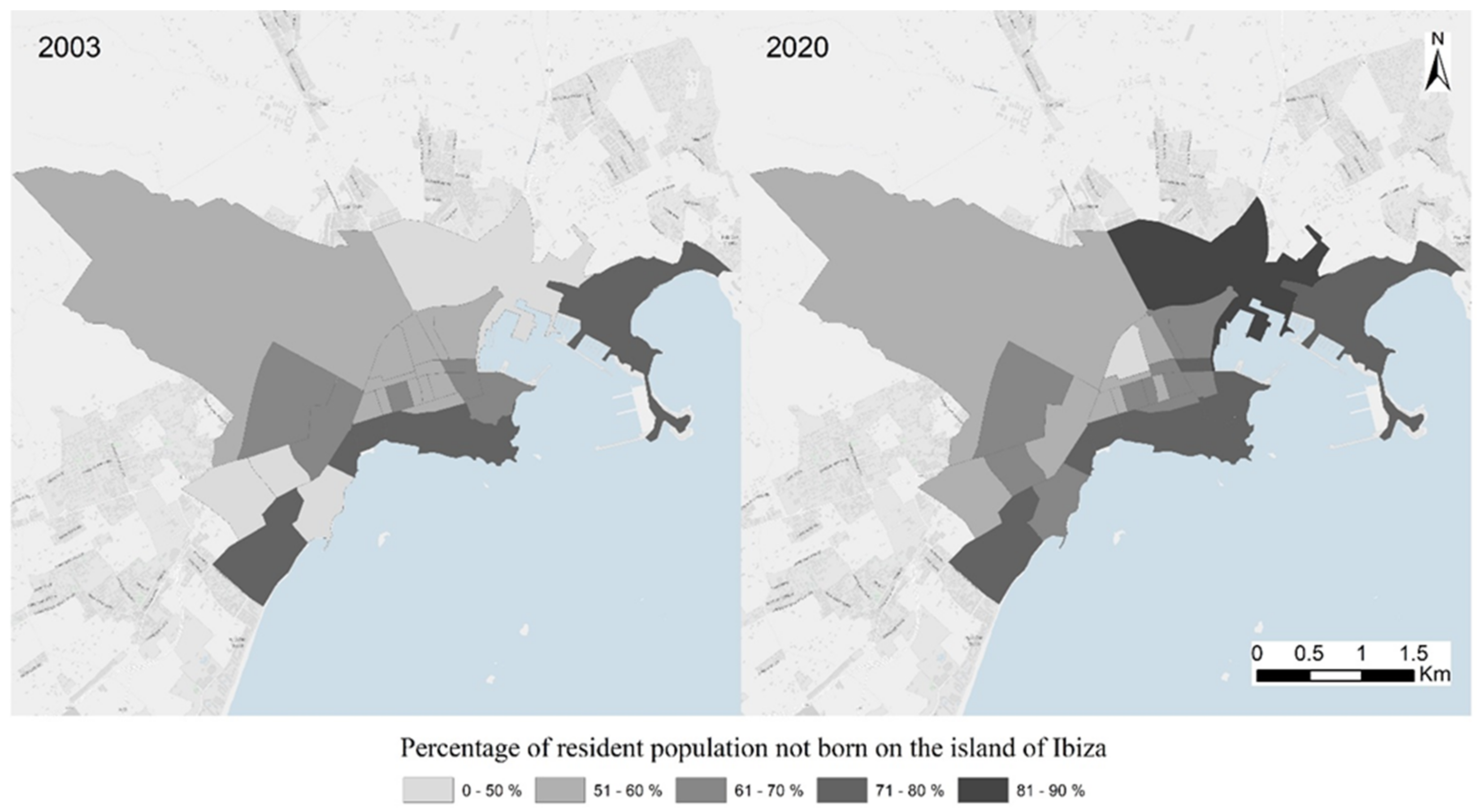

4.3. The Population’s Drift Away from the Old City: Gentrification

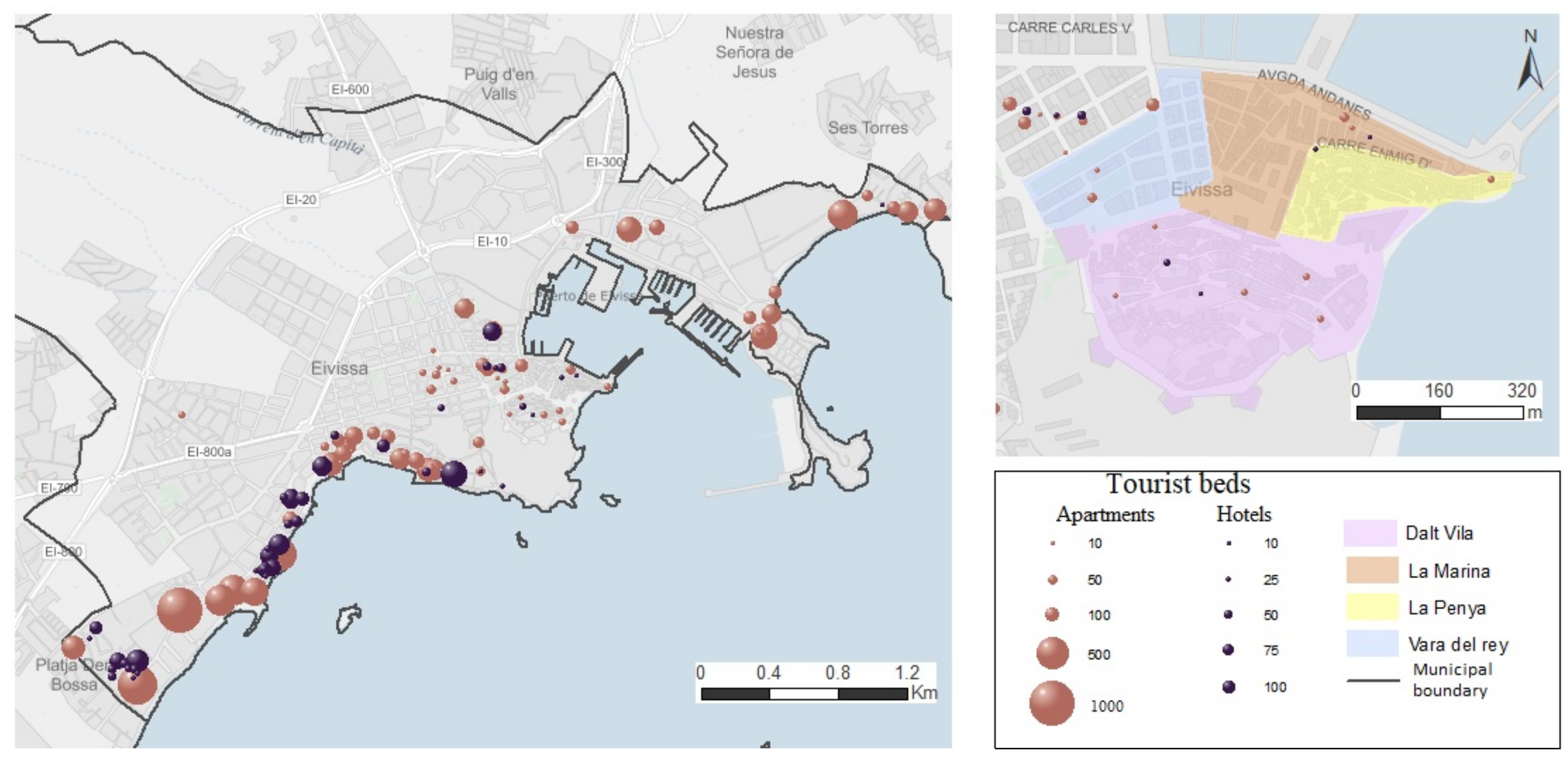

4.4. A Holiday City: Little Available Accommodation in an Area Dedicated to Complementary Leisure Services

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- González-Pérez, J.M.; Santos, X.M. Historical Cities and Tourism in Spain. In Tourism and Urban Transformation; Du, G., Ed.; Rikkyo University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2007; pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez-Salom, M.; de la Calle-Vaquero, M.; Fernández-Tabales, A.; García-Hernández, M.; Lois-González, R.C.; Mínguez-García, C.; Navalón-García, R.; Jurado, E.N.; Troitiño-Torralba, L. Diccionario de Turismo; Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hackworth, J.; Smith, N. The Changing State of Gentrification. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2001, 92, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Morales, E. Gentrification. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Studies; Anthony, M.O., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- González-Pérez, J.M. The dispute over tourist cities. Tourism gentrification in the historic Centre of Palma (Majorca, Spain). Tour. Geogr. 2019, 22, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. The New Urban Frontier. Gentrification and the Revanchist City; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, D.R.; Fainstein, S.S. The Tourist City; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.; Tallon, A. Geographies of gentrification and tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism Geographies; Wilson, J., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011; pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Gravari-Barbas, M.; Guinand, S. (Eds.) Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropo-Lises. International Perspectives; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Huning, S.; Novy, J. Tourism as an Engine of Neighborhood Regeneration? In Some Remarks Towards a Better Understanding of Urban Tourism beyond the ‘Beaten Path’; CMS Working Paper Series; Center for Metropolitan Studies: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 1–19. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.544.6506&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Gotham, K. Tourism gentrification: The case of New Orleans’ Vieux Carré (French Quarter). Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, L. Gentrification and social mixing: Towards an inclusive urban renaissance? Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 2449–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cócola, A. Tourism and commercial gentrification. In Proceedings of the RC21 International Conference, Urbino, Italy, 27–29 August 2015; Available online: https://www.rc21.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/E4-C%C3%B3cola-Gant.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- González-Pérez, J.M. A new colonisation of a Caribbean city. Urban regeneration policies as a strategy for tourism development and gentrification in Santo Domingo’s Colonial City. In Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises. International Perspectives; Gravari-Barbas, M., Guinand, S., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bures, R.M.; Cain, C. Dimensions of Gentrification in a Tourist City. In Proceedings of the 2008 Meeting of the Population Association of America, New Orleans, LA, USA, 17–19 April 2008; Available online: https://paa2008.princeton.edu/papers/81623 (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Gladstone, D.; Preau, J. Gentrification in tourist cities: Evidence from New Orleans before and after Hurricane Katrina. Hous. Policy Debate 2008, 19, 137–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzfed, M. Playing for/with Time: Tourism and Heritage in Greece and in Thailand. In Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises. International Perspectives; Gravari-Barbas, M., Guinand, S., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 233–253. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, N.; Takamitsu, J. Changing Spaces in Historical Places. In Tourism, Cultural Heritage and Urban Regeneration; Wise, N., Takamitsu, J., Eds.; Springer: Berin, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Farstad, M.; Rye, J.F. Second home owners, locals and their perspectives on rural development. J. Rural. Stud. 2013, 30, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallent, N. The Social Value of Second Homes in Rural Communities. Hous. Theory Soc. 2014, 31, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom, C.; Novy, J. Protest and Resistance in the Tourist City; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guttentag, D. Airbnb: Disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 1192–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaan, R. Airbnb, Rising Rent, and the Housing Crisis in Los Angeles. 2015. Available online: http://www.laane.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/AirBnB-Final.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Stulberg, A. How much does Airbnb impact rents in NYC? The Real Deal New York. 2015. Available online: http://therealdeal.com/2015/10/14/how-much-does-airbnb-impact-nyc-rents/ (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Lee, D. How Airbnb Short-Term Rentals Exacerbate Los Angeles’s Affordable Housing Crisis: Analysis and Policy Recommendations. Harv. Law Policy Rev. 2016, 10, 229–253. [Google Scholar]

- Mermet, A.C. Tourism gentrification in time of crisis: The case of 101 Reykjavik. In Tourism and Gentrification in Contemporary Metropolises. International Perspectives; Gravari-Barbas, M., Guinand, S., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 52–74. [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete, D. Turismo y Gentrificación en ciudades patrimoniales Mexicanas: Exclusiones socia-les a través de las transformaciones urbanas y arquitecturales en Sitios Patrimonio de la Humanidad. An. Bras. Estud. Turísticos ABET 2018, 8, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Smith, M. A critical evaluation of the global accolade The significance of World Heritage Site status for Maritime Greenwich. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2002, 82, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, T.; Zhang, T.; Fujiki, Y. The social and cultural impact of tourism development on world heritage sites A case of the Old Town of Lijiang, China, 2000–2004. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2006, 97, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Sichenze, A.; Macaione, I.; Insetti, M. The discovery of the nature-city and the regenerative strategies. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2006, 97, 104–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, A.; Pulido, J.I. El impacto del turismo en los Sitios Patrimonio de la Humanidad. Una revisión de las publicaciones científicas de la base de datos Scopus. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2015, 13, 1247–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Calle, M.; Del Río, I. La dialéctica turismo y medio ambiente en las ciudades históricas: Una propuesta interpretativa. Ería 1996, 47, 249–266. [Google Scholar]

- Troitiño, M.Á. Las ciudades españolas Patrimonio de la Humanidad. Problemática y su realidad actual. In Patrimonio Cultural de la Humanidad. Una Aproximación Geográfica; López, A., Na-ranjo, J., Eds.; Ayuntamiento de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain, 1996; pp. 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. Tourism on the Greek Islands: Issues of peripherality, competitiveness and development. Int. J. Tour. Res. 1999, 1, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A. La Triple Murada de l’Eivissa Àrab; Institut d’Estudis Eivissencs: Ibiza, Spain, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A. La Ciutat i Badia d’Eivissa; Mediterrània: Ibiza, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ramón, J. Els Monuments Antics de les Illes Pitiüses; Consell Insular d’Eivissa i Formentera: Ibiza, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cervera, L. El Triple Recinte de l’Eivissa Àrab; Mediterrània: Ibiza, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cervera, L. Els Carrers de Dalt Vila. Eivissa. La vila nova. El Buró de Santa Llúcia; Mediterrània: Ibiza, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barberán, S.; Torres, M.; Cervera, L. Esglésies d’Eivissa i Formentera; Mediterránia: Ibiza, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Prats, E. Història d’Eivissa i Formentera; Diario de Ibiza: Ibiza, Spain, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Julbe, F.; Pascuet, R. Introducción al Análisis Histórico de la Ciudad de Ibiza (De la Ciudad Púnica a 1912); Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de las Islas Baleares: Ibiza, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Posadas, E.J. La Real Fuerza de Ibiza; Imprenta Ibosim: Ibiza, Spain, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tur, A. Murades. In Enciclopèdia d’Eivissa i Formentera; Cirer, F., Ed.; Consell Insular d’Eivissa i Formentera: Ibiza, Spain, 2004; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, A. Palearo, Giovan Giacomo–el Fratín. In Enciclopèdia d’Eivissa i Formentera; Cirer, F., Ed.; Consell Insular d’Eivissa i Formentera: Ibiza, Spain, 2006; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, J.R.; Azpelicueta, M.C.; Serra, A. Ibiza, biodiversidad y cultura. Evolución y potencial turístico de un emplazamiento patrimonio mundial. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2015, 1, 109–133. [Google Scholar]

- Sansano, C. Eivissa, destí turístic. La seva realitat i la seva oferta cultural i museística. In Turisme Cultural: Anàlisi, Diagnòstic i Perspectives de Futur; Agència d’Estratégia Turística Illes Balears: Palma, Spain, 2020; pp. 149–172. [Google Scholar]

- Troitiño, M.Á. El turismo cultural en las ciudades españolas Patrimonio de la Humanidad. In Turismo Cultural: El Patrimonio Histórico como Fuente de Riqueza; Herrero, L.C., Ed.; Fundación del Patrimonio Histórico de Castilla y León: Valladolid, Spain, 2000; pp. 11–138. [Google Scholar]

- Troitiño, M.A.; Troitiño, L. Turismo y patrimonio en Castilla y León: Las ciudades Patrimonio de la Humanidad (Ávila, Salamanca y Segovia) como destinos turísticos de referencia. Polígonos 2009, 19, 145–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurrea, R.; Herrera, M. 10 anys Eivissa Patrimoni de la Humanitat 1999–2009; Ajuntament d’Eivissa: Ibiza, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vallès, R. Dalt Vila. In Enciclopèdia d’Eivissa i Formentera; Felip Cirer Costa, D., Ed.; Consell Insular d’Eivissa i Formentera: Ibiza, Spain, 2000; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- González-Pérez, J.M.; Yrigoy, I. Fluxos migratorios internacionais e patróns de localización espacial da poboación estranxeira nas cidades das Illes Balears: Palma e Eivissa. In Envellecemento Demográfico e Despoboamento. Estudos en Homenaxe a Julio Hernández Borge e José Manuel López Andión; Lois, R.C., Patiño, C.A., Durán, F.R., Eds.; Universidad de Santiago de Compostela: Santiago, Spain, 2021; pp. 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- González-Pérez, J.M.; Yrigoy, I. Descubriendo la ciudad de Ibiza. Desigualdad urbana y segregación étnica. In Nuevas Fronteras y Nuevos Horizontes en la Geografía Ibérica: Políticas y Transformaciones Territoriales; AGE and Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 2022; pp. 741–753. [Google Scholar]

- Górczyńska, M.; Lees, L.; Bang Shin, H.; López-Morales, E. Global gentrifications. Uneven development and displacement. Urban Res. Pract. 2016, 9, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julbe, F. Introducción al análisis histórico de la ciudad de Ibiza. In Introducción al Análisis Histórico de la Ciudad de Ibiza (de la Ciudad Púnica a 1912); Pascuet, R., Ed.; Collegi Oficial d´Arquitectes de Balears: Ibiza, Spain, 2011; pp. 11–70. [Google Scholar]

- González-Pérez, J.M. Les Ciutats de les Balears. Processos d´urbanització i Urbanism; Lleonard Muntaner: Palma, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Consell d’Eivissa. Diagnóstic Territorial Previ a la Revisió del Pla Territorial Insular d´Eivissa. Informes Sectorials, Recursos Ambientals i Patrimonials; Consell Insular d´Eivissa: Ibiza, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, R.; Barjuán, J.; Roig, S.; Pallejá, S.; Ferrán, A.; Giro, M.; Jover, A.; Mira, E.; Tur, F.; Cardona, J.M.; et al. Pla especial de protecció i reforma interior de sa Penya, la Marina i Vara de Rei. In Eivissa, Patrimoni de la Humanitat; Julbe, F., Ed.; Collegi Oficial d´Arquitectes de Balears: Ibiza, Spain, 2003; pp. 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- García, R. Plan Especial de protección y Reforma Interior de Dalt Vila y es Soto. In Eivissa, Patrimoni de la Humanitat; Julbe, F., Ed.; Collegi Oficial d´Arquitectes de Balears: Ibiza, Spain, 2003; pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yrigoy, I. Rent gap reloaded: Airbnb and the shift from residential to touristic rental housing in the Palma Old Quarter in Mallorca, Spain. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 2709–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yrigoy, I. Airbnb en Menorca: ¿Una nueva forma de gentrificación turística? Localización de la vivienda turística, agentes e impactos sobre el alquiler residencial. Scr. Nova 2017, 21, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Su, W. Is the World Heritage just a title for tourism? Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Tsaur, J.R.; Yang, C. Does world heritage list really induce more tourists? Evidence from Macau. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcotte, P.; Bourdeau, L. Is the World Heritage label used as a promotional argument for sustainable tourism? J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 2, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soccalia, G.; Cinàa, G. Heritage Policies in the Neoliberal Arena. Spaces of Exclusion and Gentrification in Urban World Heritage Sites. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2020, 11, 282–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpaci, J. Winners and losers in restoring Old Havana. In Cuba in Transition; Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy: Miami, FL, USA, 2000; pp. 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpaci, J. Reshaping Habana Vieja: Revitalization, Historic Preservation, and Restructuring in the Socialist City. Urban Geogr. 2000, 21, 724–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpaci, J. La transformación de los centros históricos latinoamericanos y el proceso de globalización. Rev. Geogr. 2002, 1, 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpaci, J.; Segre, R.; Coyula, M. Havana: Two Faces of the Antillean Metropolis; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baily, N. The Challenge and Response to Global Tourism in the Post-modern Era: The Commodification, Reconfiguration and Mutual Transformation of Habana Vieja, Cuba. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 1079–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K. Gentrification: What it is, why it is, and what can be done about it. Geogr. Compass 2008, 2, 1697–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtenberg, E.; Currents, R. Gentrification in Cuba? The Contradictions of Old Havana; NACLA Report on the Americas; NACLA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- González-Pérez, J.M. (Ed.) Ciudades en Transición. Procesos Urbanos y Políticas de Rehabilitación en Contextos Diferenciados: Centro Histórico de La Habana y Ciudad Colonial de Santo Domingo; Universitat de les Illes Balears: Palma, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Buzenot, L.; González-Pérez, J.M. La ville coloniale de Santo-Domingo (République Dominicaine), entre patrimonialisation et gentrification. Études Caribéennes 2018, 39–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landorf, C. Managing for sustainable tourism: A review of six cultural World Heritage Sites. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Related Monument | Promoted by | Current Use |

|---|---|---|

| Restoration of Can Botino Palace (2006) | Ibiza City Council and Ibiza World Heritage Consortium | Administrative use and the main seat of Ibiza City Council. |

| Dominican church and monastery (2014) | Ibiza City Council and Ibiza World Heritage Consortium | Administrative use (municipal offices), religious use (liturgical services in the church), and cultural use (exhibitions in the chapterhouse organized by the Contemporary Art Museum). |

| Restoration and archaeological follow-up of the Casa de la Curia (old courthouse) (2007) | Ibiza World Heritage Consortium | First, it was used as an interpretation centre for the city walls and then as a tourist information office; since 2007, it has housed the Madina Yabisa Interpretation Centre, which focuses on the period of Moslem rule. |

| Intervention at the armoury and old warehouses to extend the Contemporary Art Museum (2012) | Spanish Ministry for Culture, Ibiza City Council, and Ibiza World Heritage Consortium | Cultural facilities and Ibiza Contemporary Art Museum. |

| Restoration of Ibiza’s Renaissance city walls under the Master Plan (2001–2003) | Ibiza City Council | Public leisure purposes and image-related uses. |

| Restoration of the San Pere (2007) and San Jaume (2008) bulwarks | Ibiza World Heritage Consortium, and the Balearic Government | Cultural use: San Pere is used for concerts (upper embankment) and for informative historical material about Dalt Vila (City Wall Interpretation Centre), and San Jaume is used as a vantage point and as a setting for museumizing Dalt Vila. The casemates of both bulwarks both contain exhibition spaces. |

| Restoration of San Jordi Bulwark (2015–2016) | Spanish Ministry of Public Works and Ibiza City Council | Public space and vantage point. |

| Restoration of San Bernat Bulwark (2011–2012) | Spanish Ministry of Public Works and Ibiza City Council | Public space and museumized casemates. |

| Interventions at various points in Dalt Vila (2003–2007) | Ibiza World Heritage Consortium | Public space, cultural facilities, and varying museumization initiatives. |

| Intervention towards the castle’s infrastructure (2007) | Ibiza World Heritage Consortium | Maintenance operations. |

| Restoration of Portal Nou gate (2008–2009) | Spanish Ministry of Public Works and Ibiza City Council | Public space, cultural facilities, and entry gate to Dalt Vila’s walled area. |

| Reform and restoration of Portal de Ses Taules gate (2008–2009) | Spanish Ministry of Public Works and Ibiza City Council | Public space, cultural facilities, and main entry gate to Dalt Vila’s walled area. |

| Restoration of the arsenal of Santa Lucía Bulwark (2014) | Ibiza City Council | Cultural facilities and multipurpose space for exhibitions and other cultural events. |

| Construction of a block of council houses on Santa Creu street (2009) | Ibiza City Council | Municipal exhibition room on ground floor. |

| Refurbishment of a building on San Ciriac street (2006) | Ibiza City Council and Balearic Government | Headquarters of Ibiza City Council’s workshop school. |

| Redesign and extension of Ibiza Contemporary Art Museum (2007–2012) | Ibiza World Heritage Consortium, Spanish Ministry for Culture, and Ibiza City Council | An exhibition space housing remains of the old Punic city found at San Joan Bulwark and part of the cemetery of the old Moslem city. |

| Refurbishment of Ibiza and Formentera Archaeological Museum (2011–2012) | Spanish Ministry for Culture and Sport and Ibiza City Council | Exhibition space: the museum stands in a group of early medieval buildings under Plaza de la Catedral made up of the former Chapel of San Salvador, the Universitat (municipal corporation), and the casemate of the Santa Tecla Bulwark. It belongs to the Spanish Ministry for Culture and is run by the Balearic Government. |

| Reforms to the Diocesan Museum (1999–2006) | Ibiza World Heritage Consortium and the Bishopric | Cultural use: the museum is in the sacristy and chapterhouse of Ibiza Cathedral. |

| Creation of Puget Museum (2007) | Spanish Ministry for Culture and Ibiza City Council | Cultural use: the museum stands in a mansion known as Can Comasema. It is co-run by the Ibiza City Council and the Spanish Ministry for Culture. |

| The transfer of the Historical Archives and Newspaper Library to Can Botino (2008) | Ibiza City Council | Cultural use: for depositing and consulting archival records. |

| Refurbishment of the castle and Almudaina (2008–2022) | Spanish Ministry for Industry, Tourism, and Trade (Turespaña) | Parador Nacional de Turismo (state-run hotel), tourism facilities, and use as hotel. |

| Archaeological work in the subsoil of Dalt Vila (2018) | Ibiza City Council and Balearic Government | Archaeological excavations supervised by the Ibiza City Council’s Heritage Department. |

| Restoration of Casa Broner (La Penya district) (2012) | Ibiza City Council and Balearic Government | Multipurpose space for cultural exhibitions and acts. |

| Refurbishment of the military headquarters (2011) | Spanish Ministry of Defence, Spanish Ministry for Culture, Balearic Government, and Ibiza Island Council | The seat of the University of the Balearic Islands, the Ibiza Sound and Image Archives, and the Ibiza and Formentera Advanced Studies Centre. |

| Population (2020) | % Foreign Population (2020) | % Population over 64 Years Old (2020) | Total no. of Homes (2011) | % First Homes (2011) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palma | 24,194 | 20.77 | 15.99 | 12,855 | 76.37 |

| Maó | 921 | 18.78 | 20.41 | 535 | SD * |

| Ibiza | 2042 | 40.06 | 13.22 | 1670 | 65.56 |

| Total (Beds) | Decade of Inauguration | Category (*) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | H: GH-1 * TA: 1 | H: 2–3 * TA: 2 | H: 5 * TA: 3 | |||

| Dalt Vila | Hotels | 5 (102) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Apartments | 2 (18) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Holiday homes | 2 (6) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| La Penya | Hotels | 1 (23) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Apartments | 1 (23) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Holiday homes | 1 (2) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| La Marina | Hotels | 3 (81) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Apartments | 1 (14) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Holiday homes | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Vara de Rei | Hotels | 3 (75) | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Apartments | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Holiday homes | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Historic centre | Hotels | 12 (281) | 1 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| Apartments | 4 (55) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| Holiday homes | 3 (8) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Pérez, J.M.; Novo-Malvárez, M. Ibiza (Spain) World Heritage Site: Socio-Urban Processes in a Touristified Space. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159554

González-Pérez JM, Novo-Malvárez M. Ibiza (Spain) World Heritage Site: Socio-Urban Processes in a Touristified Space. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159554

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Pérez, Jesús M., and Margarita Novo-Malvárez. 2022. "Ibiza (Spain) World Heritage Site: Socio-Urban Processes in a Touristified Space" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159554

APA StyleGonzález-Pérez, J. M., & Novo-Malvárez, M. (2022). Ibiza (Spain) World Heritage Site: Socio-Urban Processes in a Touristified Space. Sustainability, 14(15), 9554. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159554