Financing Sustainable Development, Which Factors Can Interfere?: Empirical Evidence from Developing Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Development Financing Resources

2.2. Effects of Sustainable Development Financing Resources on Sustainability

2.2.1. The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) on Sustainable Development

2.2.2. Impact of Remittances (REMIT) on Sustainable Development

2.2.3. Effect of Official Development Assistance (ODA) on Sustainable Development

2.2.4. Impact of International Trade (TRADE) on Sustainable Development

2.2.5. Impact of Domestic Credit to Private Sector (CREDIT) on Sustainable Development

2.2.6. Impact of External Debt (DEPT) on Sustainable Development

3. Econometric Methodology and Data

3.1. Data: Source and Description

3.2. Unit Root Test in Panel

3.3. Panel Cointegration Tests

3.4. Presentation of the Model

4. Empirical Results and Discussions

5. Diagnostics Tests

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

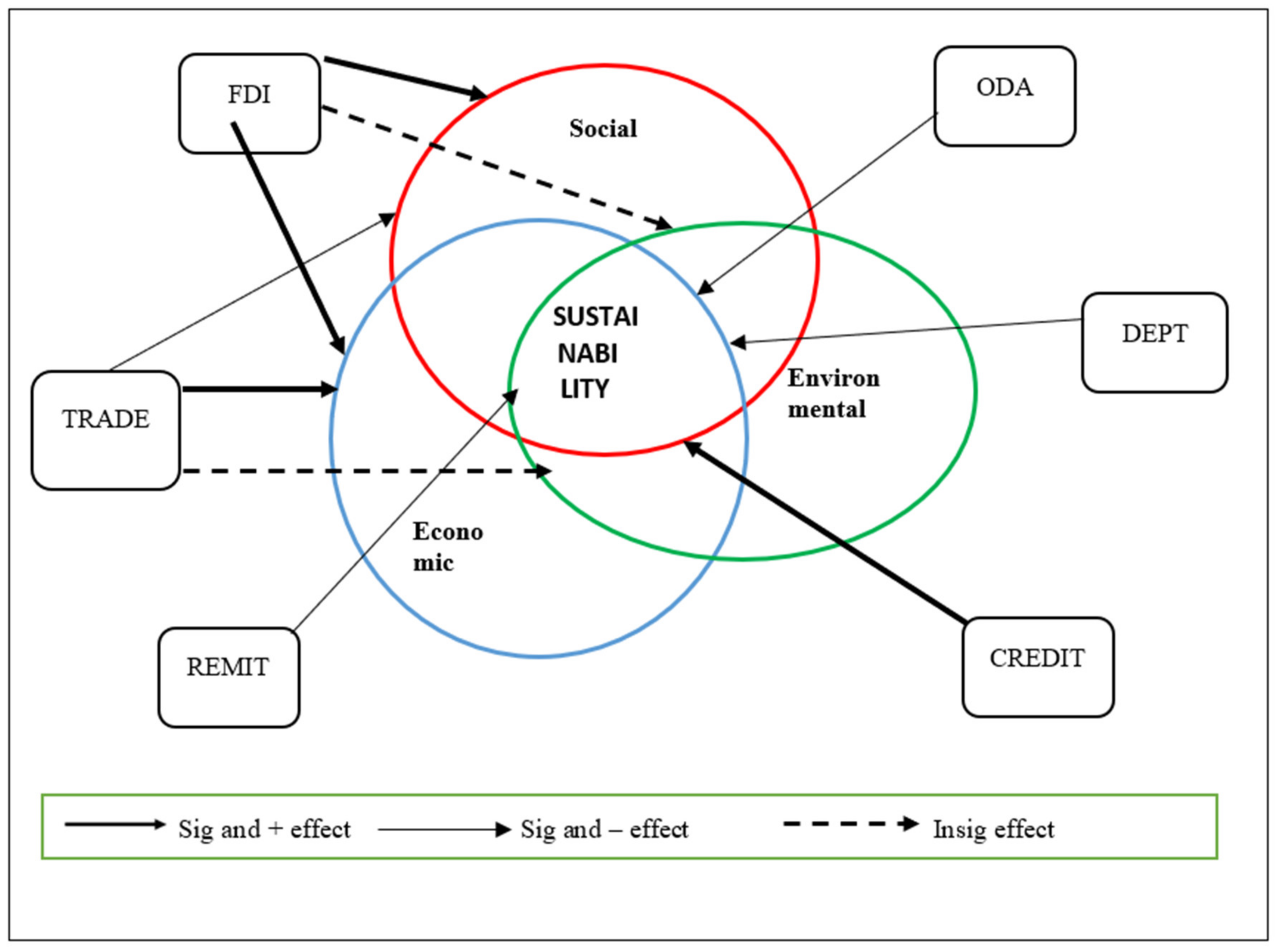

- (i)

- Theoretically, our analysis states the efficiency of development assistance, external debt, and remittances in reducing carbon emissions. However, our empirical study shows the failure of those variables in increasing economic growth and supporting human development in the case of the developing countries;

- (ii)

- Foreign direct investment can simultaneously achieve economic growth and advance social development, but it leads to environmental degradation in the developing countries. Trade openness plays a central role in promoting economic growth in both the short- and long-term; nevertheless, it inhibits human development. Both foreign direct investment and trade have no influence on the environmental quality;

- (iii)

- Contrary to our a priori expectation, domestic credit to the private sector does not significantly contribute to economic growth, but it produces a significant impact on human development. Therefore, an increase in the domestic credit to the private sector promotes human development. Although, theoretically, financial development, measured by using domestic credit to the private sector could improve the environmental performance by decreasing carbon emissions via technological development, and research and development (R&D), our study shows that domestic credit to the private sector leads to an increase in carbon dioxide emissions. Credit to the private sector through energy consumption, economic growth, and technological progress leads to higher environmental damage by contributing to an increase in carbon emissions. In effect, it helps households and firms to have funding that, respectively, permits households to buy equipment that demands energy, and firms to improve their current activities and acquire energy-demanding machines and equipment that could contribute to the growth of carbon emissions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Goals Number | Goals |

| 1 | No Poverty: End poverty in all its forms everywhere |

| 2 | Zero Hunger: End hunger, achieve food security and improve nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture |

| 3 | Good Health and Well-being: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-beingat all ages |

| 4 | Quality Education: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education andpromote lifelong learning opportunities for all |

| 5 | Gender Equality: Achieve gender equality and empower all women andgirls |

| 6 | Clean Water and Sanitation: Ensure availability and sustainablemanagement of water and sanitation for all |

| 7 | Affordable and Clean Energy: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all |

| 8 | Decent Work and Economic Growth: Promote sustained, inclusive andsustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all |

| 9 | Industry, innovation and infrastructure: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation. |

| 10 | Reduce Inequality: By 2030, reduce to less than 3 per cent the transaction costs of migrant remittances and eliminate remittance corridors with costs higher than 5 per cent |

| 11 | Sustainable Cities and Communities: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. |

| 12 | Responsible Consumption and Production: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns |

| 13 | Climate Action: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts on the environment |

| 14 | Life Below Water: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development. |

| 15 | Life on Land: Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss |

| 16 | Peace and Justice Strong Institutions: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build efficient, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels. |

| 17 | Partnership to achieve the Goal: Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize Global Partnership for Sustainable Development. |

References

- Wironen, M. Sustainable Development and Modernity: Resolving Tensions through Communicative Sustainability. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Omri, A.; Euchi, J.; Hasaballah, A.-H.; Al-Tit, A. Determinants of environmental sustainability: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 203–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awdeh, A. Financing for Development in the MENA Region. Middle East. J. Econ. Financ. 2018, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development; Report Number A/RES/69/313; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Magnus, B.; Lipsey, R.E.; Zejan, M. Is fixed investment the key to economic growth? Q. J. Econ. 1996, 111, 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Greenaway, D.; Kneller, R. Firm heterogeneity, exporting and foreign direct investment. Econ. J. 2007, 117, 134–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdouli, M.; Hammami, S. Investigating the causality links between environmental quality, foreign direct investment and economic growth in MENA countries. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanek, G.F. Aid, foreign private investment, savings and growth in less developed countries. J. Political Econ. 1973, 81, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoneman, C. Foreign capital and economic growth. World Dev. 1975, 3, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothgeb, J.M. Contagion at the Sub-War Stage: Siding in the Cold War. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci 1982, 6, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, W.J.; Boswell, T. Dependency, disarticulation, and denominator effects: Another look at foreign capital penetration. Am. J. Sociol. 1996, 102, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, L. Foreign Direct Investment and Growth: Does the Sector Matter? Working Paper; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, I.; Vu, T.B. Capital Account Liberalisation and FDI. N. Am. J. Econ. Fin. 2007, 18, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Manufacturing FDI and Economic Growth: Evidence from Asian Economies. Appl. Econ. 2009, 41, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, G.; Long, C. Did foreign direct investment put an upward pressure on wages in China? IMF Econ. Rev. 2011, 59, 404–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, X. Does foreign direct investment lead to lower CO2 emissions? Evidence from a regional analysis in China. Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 2016, 58, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastratović, R. Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Agriculture of Developing Countries. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2019, 63, 620–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula, R.; Dunning, J.H. Industrial Development, Globalisation and Multinational Enterprises: New Realities for Developing Countries. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2000, 28, 141–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamazian, A.; Chousa, J.P.; Vadlamannati, K.C. Does higher economic and financial development lead to environmental degradation? Evidence from BRIC countries. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazienza, P.; De Lucia, C.; Vecchione, V.; Palma, E. Foreign Direct Investments, Environmental Sustainability, and Strategic Planning: A Local Perspective. Chin. Bus. Rev. 2011, 10, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, K.; Eastin, J. Do Developing Countries Invest Up? The Environmental Effects of Foreign Direct Investment from Less-Developed Countries. World Dev. 2012, 40, 2221–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Public Action and the Quality of Life in Developing Countries. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 1981, 43, 287–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. From Income Inequality to Economic Inequality. South. Econ. J. 1997, 64, 384–401. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Mortality as an Indicator of Economic Success and Failure. Econ. J. 1998, 108, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Inequality Re-Examined; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chamarbagwala, R.; Ramaswamy, S.; Wunnava, P.V. The Role of Foreign Capital in Domestic Manufacturing Productivity: Empirical Evidence from Asian Economies. Appl. Econ. 2000, 32, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Gani, A. The effects of foreign direct investment on human development. Glob. Econ. J. 2004, 4, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranis, G. Economic Growth and Human Development. World Dev. 2000, 28, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Globalisation, Inequality and Global Protest. Development 2002, 45, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Financing for Development Post-2015: Improving the Contribution of Private Finance; The European Parliament Directorate-General for External Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Prabal, K.; Dilip, R. Impact of remittances on household income, asset and human capital: Evidence from Sri Lanka. Migr. Dev. 2012, 1, 163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Iheke, O.R. The effect of remittances on the Nigerian economy. Int. J. Sustain. Dev 2012, 1, 614–621. [Google Scholar]

- Baldé, Y. The impact of remittances and foreign aid on savings/investment in Sub Saharan Africa. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2011, 23, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziani, A. The Monetary Theory of Production; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rittenberg, L.; Tregarthen, T. Principles of Economics, 1st ed.; Flat World Knowledge: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; Available online: www.flatworldknowledge.com (accessed on 27 April 2022).

- Herendeen, J.B. Issues in Economics: An introduction; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, W.C.; Sprinkle, R.L. Applied International Economics, 4th ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Report Number A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R., Jr.; Page, J. Do international migration and remittances reduce poverty in developing countries? World Dev. 2005, 33, 1645–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodon, Q.; Diego, A.U.; Gabriel, G.K.; Diana O., R.; Corinne, S. Migration and Poverty in Mexico’s Southern States; Regional Studies Program, Office of the Chief Economist for Latin America and the Caribbean; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, O.; Taylor, J.E.; Yitzhaki, S. Remittances and Inequality. Econ. J. 1986, 96, 722–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Khan, Z.; Rahman, Z.U.; Khattak, S.I.; Khan, Z.U. Can innovation shocks determine CO2 emissions (CO2e) in the OECD economies? A new perspective. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2019, 30, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Bhattarai, B.; Ahmed, S. Aid, Growth, Remittances and Carbon Emissions in Nepal. Energy J. 2019, 40, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj, T. Official development assistance (ODA), public spending and economic growth in Ethiopia. J. Econ. Int. Financ. 2012, 4, 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.J.; Jang, J.Y. Analysis of ICT ODA on African Economic Growth. J. Korean Assoc. Afr. Stud. 2012, 37, 189–217. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, H.R.; Woo, M.J.; Kang, M.G. A Study on the effect of ODA’s aids and urbanization on developing countries’ economic growth through panel analysis. J. Korea Plan. Assoc. 2014, 49, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.Y. Effectiveness of Korean Official Development Assistance. Int. Bus. Rev. 2016, 20, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; Park, H.N.; Lee, S.W.; Lim, H.B. An Empirical study on the aid effectiveness of official development assistance and its implications to Korea. J. Korean. Reg. Dev. Assoc. 2016, 28, 177–198. [Google Scholar]

- Burnside, C.; Dollar, D. Aid, policies, and growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 847–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, K.B.; Enos, J.L. Foreign assistance: Objectives and conse-quences. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1970, 18, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momita, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Otsuka, K. Has ODA contributed to growth? An assessment of the impact of Japanese ODA. Jpn. World Econ. 2019, 49, 61–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluk, G.; Mert, M. Fossil & renewable energy consumption, GHGs (greenhouse gases) and economic growth: Evidence from a panel of EU (European Union) countries. Energy 2014, 74, 439–446. [Google Scholar]

- Jebli, M.B.; Youssef, S.B. The environmental Kuznets curve, economic growth, renewable and non-renewable energy, and trade in Tunisia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoundi, Z. CO2 emissions, renewable energy and the environmental Kuznets curve, a panel cointegration approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.Y.; Kim, J.S. Investigating the environmental Kuznets curve for Annex I countries using heterogeneous panel data analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 10039–10054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Choi, G.; Lee, E.; Jin, T. The impact of official development assistance on the economic growth and carbon dioxide mitigation for the recipient countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 41776–41786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Definition of ODA. Official Development Assistance-Definition and Coverage; Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2016: Taking on Inequality; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Human Development Report 2005—International Cooperation at A Crossroads—Aid, Trade and Security in An Unequal World; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2005.

- Stern, N. The Stern Review: The Economics of Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.P. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress; The Commission: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UNU-IHDP & UNEP. Inclusive Wealth Report 2012. Measuring Progress toward Sustainability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.W.; Atkinson, G.D. Capital Theory and the Measurement of Sustainable Development: An Indicator of “Weak” Sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 1993, 8, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H. Beyond Growth; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, K.; Clemens, M. Genuine Savings Rates in Developing Countries. World Bank Econ. Rev. 1999, 13, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development—An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, R. Financial Development and Economic Growth: Views and Agenda. J. Econ. Lit. 1997, 35, 688–726. [Google Scholar]

- King, R.G.; Levine, R. Finance and growth: Schumpeter might be right. Q. J. Econ. 1993, 108, 717–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriades, P.; Hussein, K. Does financial development cause economic growth? Time series evidence from sixteen countries. J. Dev. Econ. 1996, 51, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioja, F.; Valev, N. Does one size fit all?: A reexamination of the finance and growth relationship. J. Dev. Econ. 2003, 74, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A.; Hansen, B. Residual-based Tests for Cointegration in Models with Regime Shifts. J. Econom. 1996, 10, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olowofeso, E.O.; Adeleke, A.O.; Udoji, A.O. Impact of private sector credit on economic growth in Nigeria. CBN J. Appl. Stat. 2015, 6, 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, F.; Riaz, K. CO2 emissions and financial development in an emerging economy: An augmented VAR approach. Energy Policy 2016, 90, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, A.K.; Masih, M. CO2 Emissions and Financial Development: Evidence from the United Arab Emirates Based on an ARDL Approach; MPRA Paper 2017, No. 82054; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz, M.; Solarin, S.A.; Mahmood, H.; Arouri, M. Does financial development reduce CO2 emissions in the Malaysian economy? A time-series analyses. Econ. Model. 2013, 35, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Levine, R. Finance, inequality and the poor. J. Econ. Growth 2007, 12, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abosedra, S.; Shahbaz, M.; Nawaz, K. Modeling causality between financial deepening and poverty reduction in Egypt. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 126, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhrifi, A. Financial development and the “growth-inequality-poverty” triangle. J. Knowl. Econ. 2014, 6, 1163–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilian, H.; Kirkpatrick, C. Does financial development contributed to poverty reduction. J. Dev. Stud. 2005, 41, 636–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo, M.N. Is financial development a spur to poverty reduction? Kenya’s experience. J. Econ. Stud. 2010, 37, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Brid, J.; Pérez, E. Balance-of-payments-constrained growth in Central America: 1950–1996. J. Post Keynes. Econ. 1999, 22, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, G.S.; Kyophilavong, P.; Sydee, N. The casual nexus of banking sector development and poverty reduction. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2012, 2, 304–311. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, G.S.; Shahbaz, M.; Arouri, M.; Teulon, F. Financial development and poverty reduction nexus: A cointegration and causality analysis in Bangladesh. Econ. Model. 2014, 36, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyejide, T.; Soyede, A.; Kayode, M.O. Nigeria and the IMF; Heinemann Book Nigeria Ltd.: Ibadan, Nigeria, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Adebusola, A.A.; Sheu, S.A.; Elijah, O.A. The Effects of External Debt Management on Sustainable Economic Growth and Development: Lessons from Nigeria; MPRA Paper 2007, No. 2147; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, A.; Lin, C.F.; Chu, C.S.J. Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite sample properties. J. Econ. 2002, 108, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, K.S.; Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y. Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J. Econom. 2003, 115, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitung, J. The local power of some unit root tests for panel data. Adv. Econom. 2000, 15, 161–177. [Google Scholar]

- Dickey, D.A.; Fuller, W.A. Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with a 517 unit root. Econometrica 1981, 49, 1057–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.C.B.; Perron, P. Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 1988, 75, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, P.; Kalaivani, M. Exchange rate volatility and xport rowth in India: An ARDL bounds testing approach. Decis. Sci. Lett. 2013, 2, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pesaran, H.; Shin, Y. Chapter 11—An Autoregressive Distributed Lag Modelling Approach to Cointegration Analysis. In Econometrics and Economic Theory in the 20th Century the Ragnar Frisch Centennial Symposium; Strom, S., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 371–413. [Google Scholar]

- Nkro, E.; Uko, A. Autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) co-integration technique: Application and interpretation. J. Stat. Econom. Methods 2016, 5, 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, C. Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. J. Econ. 1999, 90, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P. Panel Cointegration: Asymptotic and Finite Sample Properties of Pooled Time Series Tests with an Application to the PPP Hypothesis. Econ. Theory 2004, 20, 597–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, J. Testing for error correction in panel data. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2007, 69, 709–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd, S.; Nedif Muse, A. Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Economic Growth in Ethiopia: Empirical evidence. Lat. Am. J. Trade Policy 2021, 10, 56–77. [Google Scholar]

- Caro, D.; Davis, S.J.; Bastianoni, S.; Caldeira, K. Global and regional trends in greenhouse gas emissions from livestock. Clim. Chang. 2014, 126, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Nasreen, S.; Abbas, F.; Omri, A. Does foreign direct investment impede environmental quality in high-, middle-, and low-income countries? Energy Econ. 2015, 51, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheng, V.; Sun, S.; Anwar, S. Foreign direct investment and human capital in developing countries: A panel data approach. Econ. Chang. Restruct. 2017, 50, 341–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayar, Y.; Remeikiene, R.; Androniceanu, A.; Gaspareniene, L.; Jucevicius, R. The Shadow Economy, Human Development and Foreign Direct Investment Inflows. J. Compet. 2020, 12, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyne, D. An empirical investigation of relationships between official development assistance (ODA) and human and educational development. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2008, 35, 202–221. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, J.A.; Romer, D. Does Trade Cause Growth? Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewer, J.; Hendrik Van den Berg, H. Does trade composition influence economic growth? Time series evidence for 28 OECD and developing countries. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2003, 12, 39–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S. An Econometric Analysis for CO2 Emissions, Energy Consumption, Economic Growth, Foreign Trade and Urbanization of Japan. Low Carbon Econ. 2012, 3, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawaid, S.T.; Waheed, A. Contribution of International Trade in Human Development of Pakistan. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2017, 18, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunmuyiwa, M.S. Does External Debt Promote Economic Growth? Curr. Res. J. Econ. Theory 2011, 3, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman, L.A.; Azeez, B.A. Effect of External Debt on Economic Growth of Nigeria. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 3, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ohiomu, S. External Debt and Economic Growth Nexus: Empirical Evidence from Nigeria. Am. Econ. 2020, 65, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bese, E.; Friday, H.S.; Ozden, C. The Effect of External Debt on Emissions: Evidence from China. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2021, 11, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghdoudi, K. Is the relationship between external debt and human development non-linear? A PSTR approach for developing countries. Econ. Bull. 2018, 38, 2194–2216. [Google Scholar]

- Omri, A.; Nguyen, D.K.; Rault, C. Causal interactions between CO2 emissions, FDI, and economic growth: Evidence from dynamic simultaneous-equation models. Econ. Model. 2014, 42, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdouli, M.; Hammami, S. The Impact of FDI Inflows and Environmental Quality on Economic Growth: An Empirical Study for the MENA Countries. J. Knowl. Econ. 2015, 8, 254–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaei, R.; Sameti, M. Official Development Assistance and Economic Growth in Iran. Int. J. Manag. Account. Econ. 2015, 2, 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, A.; Quinlivan, G. A Panel Data Analysis of the Impact of Trade on Human Development; Duquesne University, John F. Donahue Graduate School of Business: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Youssef, A.; Boubaker, S.; Omri, A. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Goals: The Need for Innovative and Institutional Solutions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 129, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omri, A.; Daly, S.; Rault, C.; Chaibi, A. Financial Development, Environmental Quality, Trade and Economic Growth: What Causes What in MENA Countries. Energy Econ. 2015, 48, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlin, C.; Pang, J. Are financial development and corruption control substitutes in promoting growth? J. Dev. Econ. 2008, 86, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Lean, H.H. Does financial development increase energy consumption? The role of industrialization and urbanization in Tunisia. Energy Policy 2012, 40, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, S. Does External Debt Affect Economic Growth: Evidence from Developing Countries; SBP Working Paper Series, No, 63; State Bank of Pakistan; Research Department: Karachi, Pakistan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, R.; Mustafa, U. External Debt Accumulation and Its Impact on Economic Growth in Pakistan. Pak. Dev. Rev. 2012, 51, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edo, S.; Osadolor, N.E.; Dating, I.F. Growing external debt and declining export: The concurrent impediments in economic growth of sub-Saharan African countries. Int. Econ. 2020, 161, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, P. Financing vs. Forgiving a Debt Overhang. J. Dev. Econ. 1988, 29, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borensztein, E. Debt overhang, credit rationing and investment. J. Dev. Econ. 1990, 32, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghdoudi, T.; Hakimi, A. Does external debt-poverty relationship confirm the debt overhang hypothesis for developing counties? Econ. Bull. 2017, 37, 653–665. [Google Scholar]

- Azam, M.; Shahbaz, M.; Kyophilavong, P.H.; Abbas, Q. External sources and economic growth-the role of foreign remittances: Evidence from Europe and Central Asia. J. Dev. Areas 2016, 50, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Measurement Units | Definitions | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | As measured by the GDP per capita | “GDP is the final value of the goods and services produced within the geographic boundaries of a country during a specified period of time, normally a year. GDP growth rate is an important indicator of the economic performance of a country”. The Economic Times, 18 April 2022 | WDI |

| CO2 emissions (CO2) | Is measured by the metric tons per capita | “Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a colourless, odourless and non-poisonous gas formed by combustion of carbon and in the respiration of living organisms and is considered a greenhouse gas. Emission means the release of greenhouse gases and/or their precursors into the atmosphere over a specified area and period of time”. OECD Glossary of statistical Terms, 1992 | WDI |

| Human Development Index (HDI) | Is measured by three main criteria: gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, life expectancy, and the level of knowledge/education. | “The Human Development Index (HDI) is a composite statistical index used to assess the rate of human development in a country”. The Economic Times, 18 April 2022 | UNDP |

| Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) | Foreign direct investment, net inflow (% of GDP) | “FDI is an investment made by a firm or individual in one country into business interests located in another country”. Economic Development and Revitalization | WDI |

| Remittances (REMIT) | As measured by remittances received (% of GDP) | “Remittances are largely personal transactions from migrants to their friends and families. They tend to be well-targeted to the needs of their recipients”. United Nations Development Programme | WDI |

| Official Development Assistance (ODA) | As measured by Net ODA received (% of GNI) | “(ODA) is defined as government aid designed to promote the economic development and welfare of developing countries. Loans and credits for military purposes are excluded”. OECD iLibrary | WDI |

| Trade (TRADE) | As measured by % of GDP | “Trade involves the buying and selling of goods and services, with compensation paid by a buyer to a seller, or the exchange of goods or services between parties”. Investopedia, 2021 | WDI |

| Domestic credit to the private sector (CREDIT) | As measured by % of GDP | “CREDIT refers to financial resources provided to the private sector, for example through loans, purchases of non-equity securities, and trade credits and other accounts receivable, that establish a claim for repayment”. Trading Economics, 2022 | WDI |

| External debt (DEPT) | Stocks of external debt, long-term (DOD, current US $) As measured by % of GDP | “DEPT is debt owed to nonresidents repayable in currency, goods, or services”. IGI Global, 2021 | WDI |

| Statistics | GDP | HDI | CO2 | FDI | REMIT | ODA | TRADE | CREDIT | DEBT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 3.58699 | 6.9647 | 2.313 | 3.3169 | 5.0860 | 1.8260 | 75.617 | 48.8004 | 23.8186 |

| Std. Dev | 3.24783 | 5.7804 | 2.269 | 2.7437 | 5.4466 | 2.6412 | 34.561 | 36.7542 | 1.31027 |

| Min | −10.5065 | 0.4890 | 0.174 | −2.498 | 0.0204 | −0.644 | 22.105 | 6.31035 | 20.7315 |

| Max | 16.2256 | 33.473 | 9.979 | 14.257 | 21.802 | 16.342 | 200.38 | 160.124 | 27.2300 |

| Skewness | −0.19592 | 2.0251 | 1.618 | 1.3626 | 1.3309 | 2.2832 | 0.8438 | 1.42342 | 0.29716 |

| Kurtosis | 5.29677 | 7.6754 | 4.861 | 4.7597 | 4.0436 | 8.8366 | 3.2287 | 4.20183 | 2.74792 |

| JB | 80.0733 | 564.39 | 205.7 | 155.22 | 120.57 | 810.05 | 42.785 | 140.847 | 6.14718 |

| p-value JB | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.004 *** | 0.046 * |

| Obs | 354 | 354 | 354 | 354 | 354 | 354 | 354 | 354 | 354 |

| Variables | Level | 1st Difference | Integ Level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLC | IPS | LM | LLC | IPS | LM | ||

| GDP | −8.615 ** | −6.883 ** | −5.528 ** | 10.625 | 125.025 | −7.870 | I(0) |

| HDI | −3.703 ** | −0.512 | 0.093 ** | 54.243 | 31.490 | −9.339 | I(0) |

| CO2 | −3.539 | 2.633 | 0.057 | 55.183 *** | 52.531 *** | −14.610 | I(1) |

| FDI | −5.891 ** | −4.269 ** | −3.492 | 82.255 | 97.793 | −5.150 *** | I(0) |

| REMIT | −0.724 | −2.724 ** | −4.725 ** | 74.990 | 65.406 | −7.671 | I(0) |

| ODA | −4.705 ** | −3.410 | −4.005 *** | 89.551 *** | 100.145 *** | −7.108 * | I(0) |

| TRADE | −4.472 | −1.412 | −0.956 | 57.777 *** | 66.187 | −13.559 | I(1) |

| CREDIT | −2.739 *** | 1.498 | −0.573 | 51.044 | 35.449 *** | −6.876 | I(1) |

| LNDEBT | −2.987 ** | 1.282 | −1.198 | 64.961 *** | 46.473 *** | −7.968 *** | I(1) |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | t-Statistic | p-Value | t-Statistic | p-Value | t-Statistic | p-Value |

| Kao ADF | −2.926 * | 0.0035 | −1.7905 ** | 0.0476 | −4.4401 * | 0.000 |

| Pedroni ADF | −12.455 *** | 0.0000 | −12.244 *** | 0.0017 | −12.718 *** | 0.000 |

| Westerlund | −2.506 * | 0.000 | −2.416 * | 0.007 | −2.612 * | 0.001 |

| Model 1: Dependent Variable: GDP | ||||

| Vbles | Coefficient | Standard Deviation | T-Statistic | Significance |

| D(FDI) | 0.369 | 0.005 | 3.112 | 0.113 |

| D(REMIT) | −0.640 | 0.042 | −2.015 | 0.786 |

| D(ODA) | −21.167 | 0.001 | 4.112 | 0.158 |

| D(TRADE) | 0.155 | 0.022 | 0.236 | 0.001 *** |

| D(CREDIT) | 0.083 | 0.005 | −5.378 | 0.414 |

| D(DEBT) | 1.810 | 0.007 | 1.258 | 0.229 |

| C | 32.501 | 0.080 | 1.357 | 0.000 *** |

| COINTEQ01 | −0.714 | 0.021 | 0.018 | 0.000 *** |

| R-squared 86.786 | ||||

| F-stat 7.567 | ||||

| DW Statistics 2.013 | ||||

| Model 2: Dependent Variable: CO2 | ||||

| Vbles | Coefficient | Standard Deviation | T-Statistic | Significance |

| D(FDI) | −0.098 | 0.001 | 2.168 | 0.030 ** |

| D(REMIT) | −0.935 | 0.081 | −3.287 | 0.416 |

| D(ODA) | −0.905 | 0.003 | 4.257 | 0.437 |

| D(TRADE) | −0.004 | 0.052 | 0.217 | 0.770 |

| D(CREDIT) | 0.025 | 0.002 | −0.214 | 0.504 |

| D(LNDEBT) | −0.397 | 0.006 | 3.175 | 0.579 |

| C | 2.767 | 0.052 | −2.578 | 0.000 *** |

| COINTEQ01 | −0.228 | 0.036 | 0.321 | 0.000 *** |

| R-squared 85.895 | ||||

| F-stat 7.368 | ||||

| DW Statistics 2.107 | ||||

| Model 3: Dependent Variable: HDI | ||||

| Vbles | Coefficient | Standard Deviation | T-Statistic | Significance |

| D(FDI) | −0.091 | 0.025 | 7.015 | 0.331 |

| D(REMIT) | 1.407 | 0.008 | −0.624 | 0.510 |

| D(ODA) | −5.709 | 0.061 | −8.267 | 0.400 |

| D(TRADE) | −0.019 | 0.005 | 5.024 | 0.121 |

| D(CREDIT) | −0.038 | 0.097 | 0.027 | 0.208 |

| D(LNDEBT) | 0.520 | 0.005 | −2.351 | 0.388 |

| C | 2.411 | 0.061 | 0.024 | 0.002 *** |

| COINTEQ01 | −0.159 | 0.034 | 2.157 | 0.004 *** |

| R-squared 87.998 | ||||

| F-stat 7.108 | ||||

| DW Statistics 2.004 | ||||

| Model 1: Dependent Variable: GDP | ||||

| Vbles | Coefficient | Standard Deviation | T-Statistic | Significance |

| FDI | 0.184 | 0.215 | 1.201 | 0.034 ** |

| REMIT | −0.161 | 1.092 | −4.621 | 0.023 ** |

| ODA | −0.442 | 0.302 | 3.312 | 0.081 *** |

| TRADE | 0.040 | 0.604 | −0.902 | 0.028 ** |

| CREDIT | 0.238 | 0.231 | 2.214 | 0.073 *** |

| DEBT | −1.793 | 1.701 | −0.802 | 0.064 *** |

| C | 24.421 | 0.032 | 1.708 | 0.032 |

| Model 2: Dependent Variable: CO2 | ||||

| Vbles | Coefficient | Standard Deviation | T-Statistic | Significance |

| FDI | 0.012 | 0.620 | −1.851 | 0.729 |

| REMIT | −0.488 | 0.401 | −0.271 | 0.057 *** |

| ODA | −0.921 | 1.091 | 2.032 | 0.099 *** |

| TRADE | −0.008 | 1.031 | −0.172 | 0.438 |

| CREDIT | −0.028 | 0.621 | 4.721 | 0.069 *** |

| DEBT | −0.141 | 0.817 | 2.025 | 0.537 |

| C | 9.625 | 1.015 | 2.581 | 0.084 *** |

| Model 3: Dependent Variable: HDI | ||||

| Vbles | Coefficient | Standard Deviation | T-Statistic | Significance |

| FDI | 0.250 | 2.041 | 2.651 | 0.026 ** |

| REMIT | −0.075 | 0.311 | −1.235 | 0.003 * |

| ODA | −0.406 | 1.692 | 8.027 | 0.074 *** |

| TRADE | −0.053 | 0.821 | −4.420 | 0.036 ** |

| CREDIT | 0.080 | 1.709 | 0.168 | 0.061 *** |

| DEBT | −0.319 | 1.957 | −5.182 | 0.078 *** |

| C | 2.411 | 1.487 | 0.194 | 0.088 *** |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | F-Statistics | Prob | F-Statistics | Prob | F-Statistics | Prob |

| Serial Correlation | 0.0706 | 0.925 | 0.0605 | 0.969 | 0.0704 | 0.934 |

| Heteroscedasticity | 0.387 | 0.981 | 0.331 | 0.974 | 0.314 | 0.925 |

| Normality | 2.852 | 0.483 | 2.547 | 0.521 | 2.702 | 0.361 |

| Ramsey RESE test | 0.298 | 0.264 | 0.307 | 0.352 | 0.415 | 0.251 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daly, S.; Benali, N.; Yagoub, M. Financing Sustainable Development, Which Factors Can Interfere?: Empirical Evidence from Developing Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9463. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159463

Daly S, Benali N, Yagoub M. Financing Sustainable Development, Which Factors Can Interfere?: Empirical Evidence from Developing Countries. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9463. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159463

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaly, Saida, Nihel Benali, and Manal Yagoub. 2022. "Financing Sustainable Development, Which Factors Can Interfere?: Empirical Evidence from Developing Countries" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9463. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159463

APA StyleDaly, S., Benali, N., & Yagoub, M. (2022). Financing Sustainable Development, Which Factors Can Interfere?: Empirical Evidence from Developing Countries. Sustainability, 14(15), 9463. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159463