Applying Green Human Resource Practices toward Sustainable Workplace: A Moderated Mediation Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

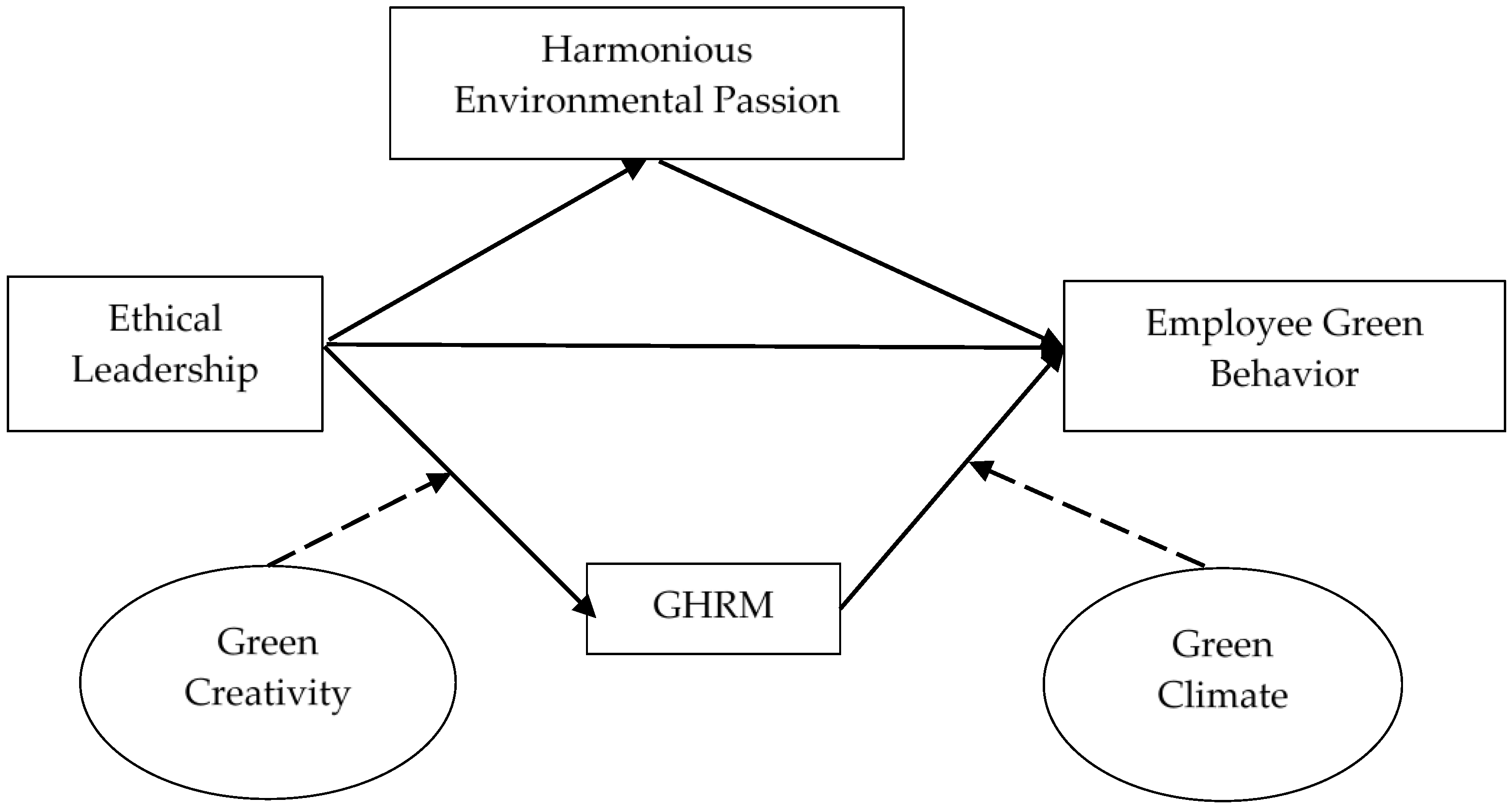

2.1. Ethical Leadership and Employee’s Green Behavior

2.2. Mediation of Harmonious Environmental Passion

2.3. Mediation of Green Human Resource Management

2.4. Moderation of Psychological Green Climate

2.5. Moderation of Green Creativity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Questionnaire and Measurements

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bansal, P.; DesJardine, M.R. Business sustainability: It is about time. Strateg. Organ. 2014, 12, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. The triple bottom line. In Environmental Management: Readings and Cases, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dillard, J.; Dujon, V.; King, M.C. Understanding the Social Dimension of Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf, L.; Benn, S. The corporation is ailing social technology: Creating a ‘fit for purpose’ design for Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, L.; Benn, S. Leadership for sustainability: An evolution of leadership ability. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.Y.; Cao, Y.; Mughal, Y.H.; Kundi, G.M.; Mughal, M.H.; Ramayah, T. Pathways towards Sustainability in Organizations: Empirical Evidence on the Role of Green Human Resource Management Practices and Green Intellectual Capital. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jamal, T.; Zahid, M.; Martins, J.M.; Mata, M.N.; Rahman, H.U.; Mata, P.N. Perceived Green Human Resource Management Practices and Corporate Sustainability: Multigroup Analysis and Major Industries Perspectives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Ramayah, T.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Sehnem, S.; Mani, V. Pathways towards sustainability in manufacturing organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of Green Human Resource Management. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 29, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, E.E.; Worley, C.G. Designing organizations for Sustainable Effectiveness. Organ. Dyn. 2012, 41, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Kusi, M.; Chen, Y.; Hu, W.; Ahmed, F.; Sukamani, D. Influencing mechanism of green human resource management and corporate social responsibility on organizational sustainable performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koberg, E.; Longoni, A. A systematic review of Sustainable Supply Chain Management in global supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 1084–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Green Human Resource Management and employee green behavior: An empirical analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, K.L.; Davis, M.C.; Russell, S.V.; Bretter, C. Employee green behavior: How organizations can help the environment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Carleton, E. Uncovering how and when Environmental Leadership Affects Employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2017, 25, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Islam, T.; Sadiq, M.; Kaleem, A. Promoting green behavior through ethical leadership: A model of green human resource management and environmental knowledge. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.-Y.; Ramayah, T.; Fawehinmi, O. Nexus between Green Intellectual Capital and green human resource management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zientara, P.; Zamojska, A. Green organizational climates and employee pro-environmental behaviour in the hotel industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1142–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Contrasting the nature and effects of environmentally specific and general transformational leadership. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, B.B.; Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting employee’s pro-environmental behavior through Green Human Resource Management Practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Qadeer, F.; Mahmood, F.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H. Ethical leadership and employee green behavior: A multilevel moderated mediation analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. On the Importance of Pro-Environmental Organizational Climate for Employee Green Behavior. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, H.; Segers, J.; van Dierendonck, D.; den Hartog, D. Managing people in organizations: Integrating the study of HRM and leadership. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 28, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Khan, M.M.; Ahmed, I.; Mahmood, K. Promoting in-role and extra-role green behavior through ethical leadership: Mediating role of green HRM and moderating role of individual green values. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 42, 1102–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Hussain, D.; Ahmed, I.; Sadiq, M. Ethical leadership and environment-specific discretionary behavior: The mediating role of Green Human Resource Management and moderating role of individual green values. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2021, 38, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Paillé, P.; Jia, J. Green Human Resource Management Practices: Scale Development and validity. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2017, 56, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, N.; Zill-E-Huma; Ali, R.; Huma, S.; Baig, A. The role of green human resource management practices and eco-innovation in enhancing the organizational performance. Vis. J. Bus. Perspect. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Ansari, N.; Raza, A.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H. Fostering employee’s pro-environmental behavior through Green Transformational Leadership, Green Human Resource Management and Environmental Knowledge. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 179, 121643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawehinmi, O.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Mohamad, Z.; Noor Faezah, J.; Muhammad, Z. Assessing the green behaviour of academics. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, N.Y.; Farrukh, M.; Raza, A. Green Human Resource Management and Employees Pro-environmental behaviours: Examining the underlying mechanism. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 28, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee Green Values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Hoang, H.T.; Phan, Q.P. Green Human Resource Management: A comprehensive review and future research agenda. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 41, 845–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Starik, M. Taoist leadership and employee green behaviour: A cultural and philosophical microfoundation of Sustainability. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 1302–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bormann, K.C.; Rowold, J. Ethical leadership’s potential and boundaries in organizational change: A moderated mediation model of employee silence. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 30, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Jianguo, D.; Ali, M.; Saleem, S.; Usman, M. Interrelations between ethical leadership, green psychological climate, and Organizational Environmental Citizenship Behavior: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, S.; Jiang, W.; Li, X.; Gao, H. Effect of employees’ perceived green HRM on their workplace green behaviors in oil and mining industries: Based on cognitive-affective system theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, G.C.; Fischer, T.; Gooty, J.; Stock, G. Ethical leadership: Mapping the terrain for concept cleanup and a future research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 2021, 32, 101471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saleem, M.; Qadeer, F.; Mahmood, F.; Han, H.; Giorgi, G.; Ariza-Montes, A. Inculcation of Green Behavior in employees: A multilevel moderated mediation approach. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021, 18, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omarova, L.; Jo, S.-J. Employee pro-environmental behavior: The impact of environmental transformational leadership and GHRM. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Ullah, K.; Khan, A. The impact of Green HRM on green creativity: Mediating role of pro-environmental behaviors and moderating role of ethical leadership style. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L.K.; Brown, M.; Hartman, L.P. A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Hum. Relat. 2003, 56, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Aquino, K.; Greenbaum, R.L.; Kuenzi, M. Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? an examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, A.; Alpaslan, C.M.; Green, S. A meta-analytic review of Ethical Leadership Outcomes and Moderators. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 139, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Donia, M.B.L.; Khan, A.; Waris, M. Do as I say and do as I do? The mediating role of psychological contract fulfillment in the relationship between ethical leadership and employee extra-role performance. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Den Hartog, D.N. Ethical leadership. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 409–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, M.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. Exploring the impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in public sector organizations: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 1405–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourigny, L.; Han, J.; Baba, V.V.; Pan, P. Ethical leadership and Corporate Social Responsibility in China: A multilevel study of their effects on trust and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, R.A.; Atan, T. The influence of ethical leadership on academic employees’ organizational citizenship behavior and turnover intention. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 583–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwepker, C.H.; Dimitriou, C.K. Using ethical leadership to reduce job stress and improve performance quality in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eluwole, K.K.; Karatepe, O.M.; Avci, T. Ethical leadership, trust in organization and their impacts on Critical Hotel employee outcomes. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmanesh, P.; Zargar, P. The Psychology of Trust [Working Title]. In Trust in Leader as a Psychological Factor on Employee and Organizational Outcome; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.-Z.; Kwan, H.K.; Yim, F.H.-K.; Chiu, R.K.; He, X. CEO ethical leadership and corporate social responsibility: A moderated mediation model. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Umrani, W.A. The impact of ethical leadership style on job satisfaction. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, V.; Wesselink, R.; Studynka, O.; Kemp, R. Encouraging sustainability in the workplace: A survey on the pro-environmental behaviour of University employees. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Environmental sustainability at work: A call to action. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 444–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.-M.; Phetvaroon, K. The effect of Green Human Resource Management on Hotel Employees’ eco-friendly behavior and environmental performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, A.; Salehzadeh, R.; Panahi, R.; Abolghasemian, S. Multiple pathways linking environmental knowledge and awareness to employees’ green behavior. Corp. Gov. 2018, 18, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. The relationship between pro-environmental attitude and employee green behavior: The role of motivational states and Green Work Climate Perceptions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 7341–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J. How green human resource management can promote Green employee behavior in China: A technology acceptance model perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luu, T.T. Green human resource practices and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: The roles of Collective Green crafting and environmentally specific servant leadership. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1167–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSuwaidi, M.; Eid, R.; Agag, G. Understanding the link between CSR and employee green behaviour. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzone, M.; Guerci, M.; Lettieri, E.; Huisingh, D. Effects of ‘green’ training on pro-environmental behaviors and job satisfaction: Evidence from the Italian Healthcare Sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Pro-environmental organizational culture and climate. In The Psychology of Green Organizations; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 322–348. [Google Scholar]

- Dasborough, M.T.; Hannah, S.T.; Zhu, W. The generation and function of moral emotions in teams: An Integrative Review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dansereau, F.; Graen, G.; Haga, W.J. A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership within formal organizations. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1975, 13, 46–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xue, J.; Li, R.; Chen, H.; Wang, T. Environmentally specific transformational leadership and employee’s pro-environmental behavior: The mediating roles of environmental passion and autonomous motivation. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.K. I second that emotion: Effects of emotional contagion and affect at work on leader and Follower Outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmanesh, P.; Zargar, P.; Esenyel, V.; Vehbi, A. Linking spiritual leadership and boundary-spanning behavior: The bright side of workplace spirituality and self-esteem. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 215824402110407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Chen, X.; Zou, Y.; Nie, Q. Environmentally specific transformational leadership and team pro-environmental behaviors: The roles of pro-environmental goal clarity, pro-environmental harmonious passion, and power distance. Hum. Relat. 2020, 74, 1864–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choong, Y.-O.; Ng, L.-P.; Tee, C.-W.; Kuar, L.-S.; Teoh, S.-Y.; Chen, I.-C. Green work climate and pro-environmental behaviour among academics: The mediating role of Harmonious Environmental Passion. Int. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 26, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umrani, W.A.; Channa, N.A.; Yousaf, A.; Ahmed, U.; Pahi, M.H.; Ramayah, T. Greening the workforce to achieve environmental performance in Hotel Industry: A serial mediation model. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusliza, M.-Y.; Norazmi, N.A.; Jabbour, C.J.; Fernando, Y.; Fawehinmi, O.; Seles, B.M. Top management commitment, corporate social responsibility and Green Human Resource Management. Benchmarking 2019, 26, 2051–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooi, L.W.; Liu, M.-S.; Lin, J.J.J. Green Human Resource Management and Green Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Do Green Culture and green values matter? Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 43, 763–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C.; Austin, W.G.; Worchel, S. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In Organizational Identity: A Reader; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Chew, I.K.H.; Spangler, W.D. CEO Transformational Leadership and Organizational Outcomes: The mediating role of human–capital-enhancing human resource management. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbeiss, S.A. Re-thinking ethical leadership: An interdisciplinary integrative approach. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Can ethical leadership inhibit workplace bullying across East and west: Exploring cross-cultural Interactional Justice as a mediating mechanism. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, N.; Nik Mahmood, N.H.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Ramayah, T.; Noor Faezah, J.; Khalid, W. Green Human Resource Management for organisational citizenship behaviour towards the environment and environmental performance on a university campus. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzi, M.; Mayer, D.M.; Greenbaum, R.L. Creating an ethical organizational environment: The relationship between ethical leadership, ethical organizational climate, and unethical behavior. Pers. Psychol. 2019, 73, 43–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, D.; Lyu, C.; Zhang, H. Does seeing “Mind acts upon mind” affect green psychological climate and Green Product Development Performance? The role of matching between green transformational leadership and individual Green Values. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Parker, S.L.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Bridging the gap between Green Behavioral Intentions and employee green behavior: The role of Green Psychological Climate. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 996–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Organisational Sustainability Policies and employee green behaviour: The mediating role of work climate perceptions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Biswas, S.R.; Abdul Kader Jilani, M.M.; Uddin, M.A. Corporate Environmental Strategy and voluntary environmental behavior—mediating effect of psychological green climate. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zibarras, L.D.; Coan, P. HRM practices used to promote pro-environmental behavior: A UK survey. Int. J. Hum. Resour. 2015, 26, 2121–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Jamshed, S.; Nisar, Q.A.; Nasir, N. Green HRM, psychological green climate and pro-environmental behaviors: An efficacious drive towards environmental performance in China. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, Measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, A. Creativity and innovation through LMX and personal initiative. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2018, 31, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Donia, M.B.L.; Shahzad, K. Impact of corporate social responsibility attributions on employees’ creative performance: The mediating role of psychological safety. Ethics Behav. 2019, 29, 490–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vasconcellos, S.L.; Garrido, I.L.; Parente, R.C. Organizational creativity as a crucial resource for Building International Business Competence. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. The Social Psychology of Creativity: A componential conceptualization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. Motivating creativity in organizations: On doing what you love and loving what you do. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1997, 40, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, A. Linking transformational leadership, creativity, innovation, and innovation-supportive climate. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 2277–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. The determinants of Green Product Development Performance: Green Dynamic Capabilities, Green Transformational Leadership, and green creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, A.; Farrukh, M.; Lee, J.-K.; Jahan, S. Stimulation of employees’ green creativity through green transformational leadership and management initiatives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, T.A.; Farooq, R.; Talwar, S.; Awan, U.; Dhir, A. Green inclusive leadership and Green Creativity in the tourism and hospitality sector: Serial mediation of green psychological climate and work engagement. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1716–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muisyo, P.K.; Su, Q.; Hashmi, H.B.; Ho, T.H.; Julius, M.M. The role of Green HRM in driving hotels’ green creativity. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 1331–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, F.; Wang, X. How green transformational leadership affects green creativity: Creative process engagement as intermediary bond and Green Innovation strategy as Boundary Spanner. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liu, H.; Chin, T.; Hu, D. The continuous mediating effects of GHRM on employees’ green passion via transformational leadership and green creativity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huo, W.; Li, X.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Yan, J. Commitment to human resource management of the top management team for Green Creativity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amabile, T.M.; Pratt, M.G. The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning. Res. Organ. Behav. 2016, 36, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasifoglu Elidemir, S.; Ozturen, A.; Bayighomog, S.W. Innovative behaviors, employee creativity, and Sustainable Competitive Advantage: A moderated mediation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cooke, F.L.; Schuler, R.; Varma, A. Human Resource Management Research and Practice in Asia: Past, present and future. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Renwick, D. Guest editorial. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seles, B.M.; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.; Jabbour, C.J.; Latan, H.; Roubaud, D. Do environmental practices improve business performance even in an economic crisis? Extending the win-win perspective. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 163, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Available online: https://lebanon.un.org/en/142648-climate-change-lebanon-threat-multiplier (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- World Bank. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country/LB (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G. Simultaneous factor analysis in several populations. Psychometrika 1971, 36, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.; Calantone, R.J. Common beliefs and reality about PLS. Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in International Marketing. Adv. Int. Mark. 2009, 20, 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- AbouAssi, K. The Third Wheel in Public Policy: An overview of ngos in Lebanon. In Public Administration and Policy in the Middle East; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 215–230. [Google Scholar]

| Constructs | Indicators | Loadings | Alpha | Rho A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Leadership | EL1 | 0.786 | 0.811 | 0.823 | 0.820 | 0.631 |

| EL2 | 0.814 | |||||

| EL3 | 0.903 | |||||

| EL4 | 0.779 | |||||

| EL5 | 0.778 | |||||

| EL6 | 0.780 | |||||

| EL7 | 0.781 | |||||

| Employee Green Behavior | EGB1 | 0.819 | 0.863 | 0.880 | 0.874 | 0.738 |

| EGB2 | 0.831 | |||||

| EGB3 | 0.822 | |||||

| EGB4 | 0.813 | |||||

| EGB5 | 0.812 | |||||

| GHRM | GHRM1 | 0.843 | 0.885 | 0.873 | 0.844 | 0.588 |

| GHRM2 | 0.865 | |||||

| GHRM3 | 0.883 | |||||

| GHRM4 | 0.781 | |||||

| GHRM5 | 0.783 | |||||

| Green Climate | GC1 | 0.884 | 0.803 | 0.835 | 0.821 | 0.712 |

| GC2 | 0.876 | |||||

| GC3 | 0.743 | |||||

| GC4 | 0.779 | |||||

| GC5 | 0.778 | |||||

| Green Creativity | GCR1 | 0.855 | 0.811 | 0.809 | 0.834 | 0.709 |

| GCR2 | 0.861 | |||||

| GCR3 | 0.873 | |||||

| GCR4 | 0.798 | |||||

| GCR5 | 0.781 | |||||

| Harmonious Environmental Passion | HEP1 | 0.892 | 0.813 | 0.827 | 0.811 | 0.714 |

| HEP2 | 0.874 | |||||

| HEP3 | 0.822 | |||||

| HEP4 | 0.789 | |||||

| HEP5 | 0.782 | |||||

| HEP6 | 0.823 |

| EL | GHRM | GC | GCR | HEP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL | |||||

| GHRM | 0.611 | ||||

| GC | 0.750 | 0.436 | |||

| GCR | 0.748 | 0.499 | 0.526 | ||

| HEP | 0.711 | 0.422 | 0.510 | 0.564 | |

| EGB | 0.575 | 0.466 | 0.487 | 0.502 | 0.514 |

| Effects | Relations | Β | t-Statistics | Ƒ2 | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | |||||

| H1 | EL → EGB | 0.314 | 5.231 *** | 0.123 | Supported |

| Mediation | |||||

| H2 | EL → HEP → EGB | 0.115 | 2.872 ** | 0.031 | Supported |

| H3 | EL → GHRM → EGB | 0.133 | 2.206 * | 0.023 | Supported |

| Interaction | |||||

| H4 | GHRM × GC → EGB | 0.148 | 2.338 * | 0.043 | Supported |

| H5 | EL × GCR → GHRM | 0.143 | 2.678 ** | 0.048 | Supported |

| Control Variables | |||||

| Gender → EGB | 0.148 | 2.360 * | |||

| Age → EGB | 0.106 | 2.176 * | |||

| Experience → EGB | 0.122 | 2.245 * | |||

| R2HEP = 0.31/Q2HEP = 0.19 R2GHRM = 0.37/Q2GHRM = 0.24 R2EGB = 0.39/Q2EGB = 0.29 SRMR: 0.026; NFI: 0.924 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chreif, M.; Farmanesh, P. Applying Green Human Resource Practices toward Sustainable Workplace: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159250

Chreif M, Farmanesh P. Applying Green Human Resource Practices toward Sustainable Workplace: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159250

Chicago/Turabian StyleChreif, Maya, and Panteha Farmanesh. 2022. "Applying Green Human Resource Practices toward Sustainable Workplace: A Moderated Mediation Analysis" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159250

APA StyleChreif, M., & Farmanesh, P. (2022). Applying Green Human Resource Practices toward Sustainable Workplace: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Sustainability, 14(15), 9250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159250