Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine how residents in Novi Sad (The European Capital of Culture 2022) perceive the influence of cultural involvement and place attachment on their attitude toward tourism, and how this affects their support for tourism development. In order to investigate the relationships between these factors, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used. The proposed model was tested, and the findings show significant relationships between residents’ cultural involvement, place attachment, perceived positive and negative impacts of tourism (economic, socio-cultural, environmental), and support for tourism development. The findings of the study could assist tourism planners not only in Novi Sad but also in other urban destinations.

1. Introduction

Numerous studies have been conducted in recent years to assess inhabitants’ attitudes and perceptions of the influence of tourism development in their local communities [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Tourism development, in particular, has a multitude of economic, sociological, and environmental consequences for the host destination and its inhabitants [15]. Because the local community is a vital stakeholder in the tourism sector, it is difficult to establish sustainable tourism development without their cooperation [9]. Regarding the theories used to describe this concept, the social exchange theory (SET) has been one of the most commonly employed [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Ap (1992) was the first to use SET in the tourism literature to describe the interactions between locals and the effects of tourism. Residents, according to the previous findings, are more likely to support tourism growth if they feel the advantages will exceed the risks [6,22,25].

The success of tourist expansion at a location is dependent on how local inhabitants view and support tourism’s advantages from the host community’s perspective. It is important to prioritize the comprehension of the expectations and goals of communities before planning and growing tourism [26]. While urban destinations increasingly see tourism as an essential instrument for restoring and rejuvenating economic growth, tourism planners must pay special attention to place-based attitudes and local population expectations [21,27]. The attitude of inhabitants toward tourism development is critical because a harmonious relationship between visitors and residents has a substantial impact on visitors’ satisfaction with the location [28]. Moreover, pleasant and kind hospitality may increase the destination’s attractiveness and promote a memorable and satisfying journey for guests. Understanding how communities perceive the consequences of tourism can shed light on how to maximize benefits while avoiding costs [24].

As mentioned above, scholars have observed that communities favor tourism development when they expect more positive tourist-related advantages, yet most research has ignored the influence of cultural features on inhabitants’ sentiments [11].

This study intends to address the current research gap in previous studies by investigating citizens’ opinions of tourism development from the standpoint of cultural involvement.

Besides this, place attachment has also been studied in the tourism context as a factor influencing inhabitants’ attitudes toward tourism development. There is a little research on how place attachment affects citizens’ perspectives of the benefits of tourism development, as well as their support of it [6,9,24,27,29,30].

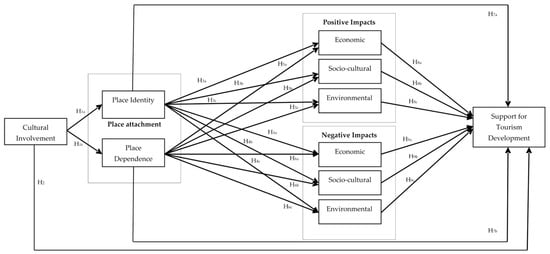

Based on current evidence, this study established a model to analyze the effect of citizens’ place attachment and cultural involvement on their attitude toward tourism, which ultimately influences their support for tourist growth. The primary goal of this study is to determine whether people’s cultural involvement influences their sense of place and willingness to support tourism-related development. The second objective is to find out if residents’ opinions of the tourism impacts and their supportive behavior are influenced by place attachment. Last but not least, this study tries to find out if locals’ opinions on the tourism impacts influence their support for tourism growth (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed model of research.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Impact of Cultural Involvement on Place Attachment and Attitudes toward Tourism Development

A range of scholars is interested in learning more about how people establish relationships with locations. For example, anthropology aims to comprehend the cultural significance of places in everyday life [31]. Cultural participation is based on the distinctive culture of the residents’ living environment, and adds to the spiritual world of the inhabitants. Cultural participation, in this sense, encapsulates a certain cultural community life area that might impact a resident’s spiritual wellbeing and so promote a better connection with the place of living [11]. According to Rapacciuolo et al. [32], cultural involvement, for instance, is the second-best predictor of psychological wellbeing after (the presence or absence of) serious disorders, and it has a far higher influence than characteristics like income, age, gender, or career. Individuals’ emotional, social, or mental participation with culture-related activities, events, or performances, through which residents are exposed to traditional cultures and festivals, is referred to as ‘cultural involvement’ in this study. Residents who are more familiar with the local culture and local cultural activities are more likely to identify with their destination. Furthermore, according to Spennemann [33], cultural heritage has an important role in shaping community identity and the perception of place attachment, which can also positively impact personal and community mental health. On the other hand, according to self-confidence theory, greater knowledge may boost residents’ pride and confidence in their own culture, encouraging them to welcome visitors as a way of sharing their local cultural activities and events with others [34].

An effective relationship or link between people and certain locations is defined as ‘place attachment’ [35]. Some researchers define place attachment as any connection a person has—positive or negative—with a certain location [35,36]. Place attachment is a term used by environmental psychologists to describe the bond that exists between people and their surroundings [37]. Backlund and Williams [38] found that the concept of place attachment consists of two dimensions: place identity, which relates to a psychological or subjective connection to a place, and place dependence, which denotes a functional engagement with a place [39]. This dimensionality is well acknowledged in both tourism management studies [7,11,39,40] and environmental psychology [41,42,43,44]. Despite the fact that place identity and place dependence are two the most-often-explored dimensions of place attachment, the scales and items used to assess them differ greatly. Williams and Vaske’s [44] final scale, for example, has five items to assess place identity and five items to assess place dependence. White et al. [45] use five items for place identity and four items for place dependence, whereas Ispas et al. [46] employs nine items to measure place identity and five to measure place dependence. The scales used in this research were derived by Boley et al. [47], based on original studies [42,44,48,49] conducted on seven samples in four countries (United States, Cape Verde, Nigeria, and Poland). Boley et al. [47] presented a final scale that is reliable in different cultures. The aforementioned scale is appropriate for the analysis of residents’ attitudes in Novi Sad because it is a multicultural city with around twenty different nations and national or ethnic groups living in it, each with their own distinct culture [50].

As reported by Besculides et al. [51] residents can prosper from tourism in one of two ways. To begin with, tourism exposes the host to various cultures, which can lead to positive outcomes such as tolerance and understanding. Second, expressing local culture to tourists increases one’s understanding of what it means to live in a community, resulting in increased identification, pride, togetherness, and support. On the basis of this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Cultural involvement has a positive effect on place attachment (place identity).

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Cultural involvement has a positive effect on place attachment (place dependence).

Hypothesis 2.

Cultural involvement has a positive effect on residents’ attitudes toward tourism development.

2.2. The Effect of Place Attachment on Perceived Tourism Impacts and Support for Tourism Development

For this study, place identification theories served as the conceptual framework for the place attachment construct. Therefore, place dependency and place identity are masured as dimensions of place attachment [52]. Self-identification has a significant impact on how people behave in the context of a tourism destination. Place identity influences local attitudes toward tourism and support for tourism, and self-identification has an important role in this relationship [22]. According to Wang and Chen [21], the sense of place at the tourism site was crucial in shaping inhabitants’ attitudes toward tourism. According to some researchers, the better the feeling of a place of a tourist location, the more likely inhabitants are to have a favorable attitude toward tourism [20,29,53]. Eusébio et al. [7] performed a study on Boa Vista Island, Cape Verde, and discovered that locals’ place attachment positively influenced how they perceived the tourist growth. Gursoy, Jurowski and Uysal [18] discovered that when residents perceive a greater need for larger investments in local economy, they prefer to highlight the positive effects of tourism while neglecting the negative effects. Residents’ attachment to a community is regarded as being connected to their willingness to support tourism development in their community [54]. According to Mason and Cheyne [55], inhabitants are more inclined to support tourism if they believe the tourist sector is compatible with their place identities, and a location is more likely to be addressed by people who have a high level of participation in the tourism industry. People are more likely to support the growth of their community if they care about it [56]. Based on very scarce literature regarding the link between place attachment, residents’ perceptions of tourist impacts, and attitudes toward tourism development, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3a (H3a).

Place attachment (place identity) has a positive effect on residents’ perceptions of positive economic impacts;

Hypothesis 3b (H3b).

Place attachment (place identity) has a positive effect on residents’ perceptions of positive socio-cultural impacts;

Hypothesis 3c (H3c).

Place attachment (place identity) has a positive effect on residents’ perceptions of positive environmental impacts;

Hypothesis 4a (H4a).

Place attachment (place identity) has a negative effect on residents’ perceptions of negative economic impacts;

Hypothesis 4b (H4b).

Place attachment (place identity) has a negative effect on residents’ perceptions of negative socio-cultural impacts;

Hypothesis 4c (H4c).

Place attachment (place identity) has a negative effect on residents’ perceptions of negative environmental impacts;

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

Place attachment (place dependence) has a positive effect on residents’ perceptions of positive economic impacts;

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

Place attachment (place dependence) has a positive effect on residents’ perceptions of positive socio-cultural impacts;

Hypothesis 5c (H5c).

Place attachment (place dependence) has a positive effect on residents’ perceptions of positive environmental impacts;

Hypothesis 6a (H6a).

Place attachment (place dependence) has a negative effect on residents’ perceptions of negative economic impacts;

Hypothesis 6b (H6b).

Place attachment (place dependence) has a negative effect on residents’ perceptions of negative socio-cultural impacts;

Hypothesis 6c (H6c).

Place attachment (place dependence) has a negative effect on residents’ perceptions of negative environmental impacts;

Hypothesis 7a (H7a).

Place attachment (place identity) has a positive effect on residents’ support for tourism development;

Hypothesis 7b (H7b).

Place attachment (place dependence) has a positive effect on residents’ support for tourism development.

2.3. Perceived Tourism Impacts and Their Effect on Support for Tourism Development

Tourism may have both beneficial and harmful consequences. Residents consider these effects while forming opinions on tourism [8]. Their attitudes will decide whether or not they favor tourism growth [57]. According to the relevant research, tourism has generally recognized economic, socio-cultural, and environmental implications [16,18,57,58].

The economic impacts, as identified by several researchers, include common and personal interests that contribute to the following: increased employment opportunities [55,59,60,61,62,63,64,65], income, and standard of living [5,58,59,60,62,63,64,65,66]; increased investment and development opportunities [58,59,60,61,63,64,65,66]; the creation of the possibility of new local businesses [67]; and the enhancement of the local and regional economies [59,60,62]. In addition to the positive ones, the researchers also identified negative economic impacts such as: increases in the price of goods and services, increases in tax revenues [58,60,66,67,68], and increases in real estate prices [69,70]. Previous research indicates the existence of both positive and negative socio-cultural implications of tourism on local communities. It identifies that tourism development contributes to the improvement of cultural connections between the local population and tourists [66], provides residents a chance to meet new people [15], increases the availability of recreational facilities [66], affects cultural identity [2], encourages various educational activities for children [5], and urges residents to be proud of their heritage [2,5]. On the other hand, increased tourism may cause overcrowded tourism facilities [15] and traffic jams on the roads [55,58,60,61], as well as a rise in the availability of narcotics, crime, prostitution, public alcohol drinking [5,58,63], stereotypes [71], and discrimination against tourists by residents [72]. In addition, from an ecological point of view, the development of tourism can contribute to negative phenomena such as increasing litter [58,59,60], noise pollution [58,59,60], and the overcrowding of recreational areas in the open [5,58], etc.

On the other hand, the environmental benefits of tourism development are the following: the conservation of natural areas and parks [59,60,63]; the restoration of historical buildings, roads, and public facilities [66]; and an increasing number of parks and other places for community recreation [64].

The empirical studies in the last 40 years show that citizens’ opinions of tourist impacts have been thoroughly examined, but with very different findings [56]. In general, locals acknowledge that all of the effects—economic, sociocultural, and environmental—have an impact on how they feel about tourism development, both favorable and unfavorable [65]. According to SET, locals’ attitudes toward tourism development are influenced by the appraisal of the perceived benefits and costs of travel, which affects both favorable and unfavorable attitudes towards travel. Many researchers have found that communities’ support for tourism development was significantly influenced by both positive and negative sentiments about tourism [20,22]. Furthermore, SET implies that good perceptions of effects lead to positive attitudes, but negative perceptions are likely to have a detrimental impact on attitudes [15]. The following hypotheses can be developed as a result:

Hypothesis 8a (H8a).

Residents’ perceptions of positive economic impacts have a positive effect on residents’ support for tourism development.

Hypothesis 8b (H8b).

Residents’ perceptions of positive socio-cultural impacts have a positive effect on residents’ support for tourism development.

Hypothesis 8c (H8c).

Residents’ perceptions of positive environmental have a positive effect on residents’ support for tourism development.

Hypothesis 9a (H9a).

Residents’ perceptions of negative economic impacts have a negative effect on residents’ support for tourism development.

Hypothesis 9b (H9b).

Residents’ perceptions of negative socio-cultural impacts have a negative effect on residents’ support for tourism development.

Hypothesis 9c (H9c).

Residents’ perceptions of negative environmental have a negative effect on residents’ support for tourism development.

3. Methodology

3.1. Location of the Study Area

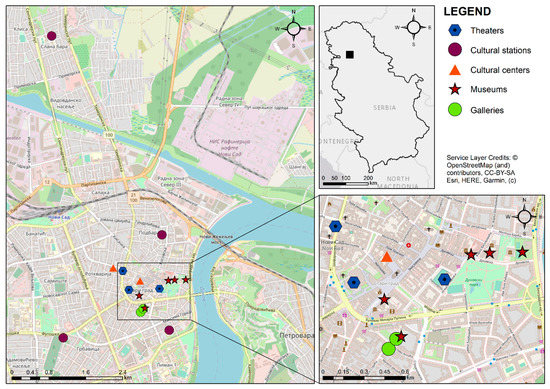

A survey was carried out in Novi Sad, the second largest city in Serbia and the capital of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina. Novi Sad, the Autonomous Province (AP) of Vojvodina’s political, administrative, academic, and cultural hub, is home to numerous esteemed regional cultural and artistic institutions, both urban and rural. Novi Sad submitted its candidacy for European Capital of Culture as a tolerant, international, multi-religious, and multicultural society [73]. Novi Sad has 9 city zones and 15 suburban areas with around 400,000 inhabitants. Many projects focus on bringing people of various national communities together and improving their status through art and culture. The goal in this sector is to promote the city’s variety, as well as intercultural cooperation and culture as a tool for addressing societal disputes.

Novi Sad won the most prestigious title in the sphere of culture in the European Union in 2016, the title of European Capital of Culture in 2022, with the slogan “For New Bridges”. Shortly afterwards, the Government of the Republic of Serbia deemed this project to be of national importance. The programme narrative of Novi Sad 2022 stems from the 4 New Bridges slogan: The Love Bridge, the Freedom Bridge, the Hope Bridge, and the Rainbow Bridge, which represent the establishment of a balance between available resources and the city’s attractions. Each bridge has two program arcs that answer critical concerns about the city’s current social context, legacy, and modern innovation in light of current European and global events [73]. Numerous spatial capacities have been expanded, new spaces have been built or new ones have been renovated—over 40,000 square meters of space for culture. The suburbs of the Petrovaradin fortress from the 17th century were renovated after 300 years. In the Almaški region, which is associated with modern development from the 18th century, the former silk factory was renovated into a new Svilara Cultural Station. This influenced this part of the city to be included as a protected cultural and historical entity in the “Faro Network” of the Council of Europe for Heritage Preservation.

The space and the square around the oldest professional theater in Serbia were renovated. Then, not far from the Danube, the industrial zone was transformed into the Creative District, which is a unique center of youth and contemporary creativity. Moreover, a network of cultural stations was developed, as a new and unique model in culture. Eight new and renovated buildings were converted into cultural stations (Svilara, Barka, Mlin, Eđšeg, Bukovac Cultural Station, Rumenka Cultural Station, Cultural Caravan (mobile cultural station), and Liman–Chinatown Cultural Station—Figure 2). Finally, fellow citizens were engaged through the project “New Places” by proposing new locations and spaces that should be intended for socializing and culture, and which would then be arranged for that purpose [73].

Figure 2.

Map of Novi Sad with the locations of the cultural sites. Source: Google Earth, July 2022; https://d-maps.com/, accessed on 8 June 2022, modified by Marija Cimbaljević and Dajana Bjelajac.

3.2. Questionnaire Development

The questionnaire used in this study consisted of two parts. The first part measured the main sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, including age, gender, educational level, employment status, family status, residents’ period of living in Novi Sad and its suburban settlements, and the part of the city in which they live. The second part consisted of ten rating scales that present the key components of the study model: cultural involvement, place attachment as measured with two scales (place identity and place dependence), perceived tourism positive impacts (economic, socio-cultural and environmental), perceived tourism negative impacts (economic, socio-cultural and environmental), and residents’ support for tourism. For perceived positive and negative socio-cultural impacts, the researchers used ten statements developed from the existing literature [5,57,58,60,61,63,64,66,74]. Perceived positive and negative economic impacts were measured using ten items [5,56,57,58,60,64,65,66,67,70]. Six statements represented perceived positive and negative environmental impacts [5,57,58,59,61,63,64,66,67,74,75]. In order to assess cultural involvement, five items were selected from previous studies [11,76]. Place identity and place dependence were measured by the Abbreviated Place Attachment Scale (APAS) adjusted by Boley et al. [47] based on previous studies [42,44,48,49]. The authors used six items for each construct. Support for tourism was measured using a six-item scale derived from Nukoo and Ramkissoon [23] and Nukoo and So [77]. All of the items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), (Supplementary Materials).

3.3. Data Collection

A self-administered survey was distributed to find out how residents perceive tourism effects: economic, sociocultural, and environmental. Using a convenience sampling technique, the data were gathered from January to May 2022. Residents of Novi Sad over the age of 18 were the target population. For the data collection, the online survey and standard paper and pen survey were combined. The online questionnaire was distributed through individual emails, mailing lists, and social media platforms, and posted on the website of the Foundation “Novi Sad—European Capital of Culture”. A total of 579 residents answered the questionnaire. Due to numerous missing values, a total of 42 questionnaires were excluded from the analysis. Finally, 537 valid questionnaires were processed using R and RStudio (lavaan, semPlot, and semTools packages), which were used for the CFA (Confirmatory Factorial Analysis) and SEM analyses.

4. Results

4.1. Study Sample

The sample consisted of 537 residents of Novi Sad. There was a higher number of males in the sample (54.4%), while the average age of the sample was 33.41 years (age range 18–72). There was also the highest number of those who have finished faculty or college (41.9%). Married residents were predominant in the sample (37.4%), followed by those who are in a relationship (27.7%). Most of the respondents have incomes in the range 45,001–70,000 RSD (47.3%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The sample characteristics (N = 537).

From the total number of respondents, 61.6% live in Novi Sad and its suburban areas, while (38.4%) live in suburban settlements. It is important to mention that 33.89% had lived in Novi Sad from the birth, 15.83% had lived in Novi Sad for up to 30 years, 14.15% had lived in Novi Sad for up to 20 years, 23.09% had lived in Novi Sad for up to 10 years, and 13.04% had lived in Novi Sad for up to 5 years.

Based on the t-test of the independent samples, it was determined that statistically significant differences in the attitudes of the respondents in relation to the part of the city in which the respondents live (two groups: suburban settlements and the city of Novi Sad) exist only in the negative environmental impacts factor, in that the respondents from NS gave a significantly higher score compared to the respondents from suburban settlements (t = 3.536; p = 0.000; Novi Sad M = 2.726; Suburban M = 2.356). This means that the respondents from Novi Sad are more affected, that is, they perceive the negative impacts of tourism (environmental) more strongly than those who live in the suburbs, which is logical because they face problems such as traffic jams, noise, pollution, an increased amount of garbage, and crowding in parks and recreation areas.

4.2. Measurement Model Validity—Confirmatory Factorial Analysis (CFA)

Confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA) was used to estimate the latent components measurement model and test it for construct validity and reliability. The initial model fit indices showed satisfactory results, except RMSEA and SRMR, which were above the limit value of 0.08 (CFI = 0.958, TLI = 0.953, RMSEA = 0.107, SRMR = 0.099); consequently, possible model flaws were revealed. Consequently, the modification indices were consulted. Beaujean [78] states that a “troublingly large” residual is “>0.1”; thus, five items in total with high residuals were excluded (Table 2). Therefore, a model with a satisfactory fit was established (CFI = 0.989, TLI = 0.976, RMSEA = 0.078, SRMR = 0.052).

Table 2.

CFA results.

The average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were used to assess the scale’s reliability. Furthermore, AVE was used to access convergent validity. Convergent validity is achieved when all item-to-factor loadings are significant and the AVE score is higher than 0.50 within each dimension [79]. The composite reliability values for the latent factors exceeded the recommended minimum value of 0.7 [80,81]. According to the data shown in Table 2, all of the dimensions had AVE values greater than 0.50 and CR values greater than 0.70, which shows good convergent validity. The findings revealed that each factor’s Cronbach’s alpha values were higher than 0.70, with a radius spanning from 0.809 to 0.902 [82].

The discriminant validity was determined by comparing the square root of each AVE to the correlation coefficients for each construct. The square roots of the AVE values were greater than the correlation values in the case of each construct, which demonstrated discriminant validity [79] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Discriminant validity assessment.

Moreover, we tested our study for the common method bias (CMB) issue. CMB happens when variations in responses are caused by the instrument rather than the actual predispositions of the respondents that the instrument attempts to uncover. One of the ways to test if CMB is of concern is Harman’s single factor score, in which all of the items (measuring latent variables) are loaded into one common factor. If the total variance for a single factor is less than 50%, it suggests that CMB does not affect the data [83]. In this study, we tested CMB with Harman’s single factor score, and revealed that the items of latent variables load into a single factor and explain 41.13% of the total variance, meaning that CMB is not of concern for this study.

4.3. Results of the Path Model

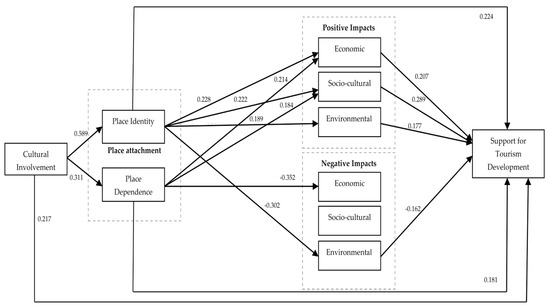

Firstly, the model’s validity was examined, and it showed satisfactory fit indexes (CFI = 0.951; TLI = 0.946; RMSEA = 0.053; SRMR = 0.074). The fit indices were adequate for addressing each latent factor’s postulated interrelationships in the proposed model (Table 4). Cultural involvement regading Place identity (β = 0.589, p < 0.000), Place dependence (β = 0.311, p < 0.000) and Support for tourism development (β = 0.217, p < 0.000) indicated significant and positive impact, thus supporting H1a, H1b, and H2. Place identity had a significant positive effect on perceived positive economic (β = 0.228, p < 0.000) and socio-cultural impacts (β = 0.222, p < 0.000), environmental impacts (β = 0.189, p < 0.000) and support for tourism development (β = 0.224, p < 0.000), so H3a, H3b, H3c and H7a can be confirmed. Place identity did not have a significant negative effect on negative economic (β = −0.061, p = 0.137) or negative socio-cultural impacts (β = −0.055, p = 0.129), which didn’t confirm H4a and H4b. H4c was supported, indicating that place identity had a significant negative effect on negative environmental impacts (β = −0.302, p < 0.000). Further, place dependence indicated a significant positive impact on perceived positive economic (β = 0.214, p < 0.000) and socio-cultural impacts (β = 0.184, p < 0.000), and support for tourism (β = 0.224, p < 0.000), and a significant negative impact on negative environmental impacts (β = −0.352, p < 0.000), which confirmed hypotheses H5a, H5b, H7a and H6a. Place dependence was not found to positively affect positive environmental impacts (H5c) (β = 0.016, p = 0.178), and was not found to negatively affect perceived negative socio-cultural (β = −0.029, p = 0.165) or environmental impacts (β = −0.031, p = 0.149), so H5c, H6b and H6c cannot be confirmed. The perceived positive economic (β = 0.207, p < 0.001), socio-cultural (β = 0.289, p < 0.000) and environmental (β = 0.177, p < 0.000) impacts of tourism had a significant positive effect on support for tourism, thus supporting H8a, H8b and H8c. Perceived negative environmental impacts (β = −0.162, p < 0.000) had a significant negative effect on support for tourism development. These results supported H9c. Negative economic (β = −0.031, p = 0.152) and socio-cultural (β = −0.057, p = 0.128) impacts were not found to negatively affect support for tourism; thus, we rejected H9a and H9b. The results of the path model are shown in Table 4 and Figure 3.

Table 4.

The results of model (standardized regression weights).

Figure 3.

The results of the path model based on standardized regression weights.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The following are the key conclusions and debates based on empirical studies of data from Novi Sad’s inhabitants. As hypothesized, the findings indicate a positive relationship between cultural involvement, place attachment (place identity and place dependence), and support for tourism. Because the host culture is an important component in the tourist setting, and because cultural participation is a more long-lasting and internal motivating factor, it was crucial to investigate whether residents’ level of involvement in cultural activities impacts their place attachment and their attitude towards tourism development. Cultural involvement is one strategy to encourage residents to connect with their culture and traditions. It is supposed that residents will therefore have a stronger feeling of belonging and identity, which will inspire them to support sustainable tourism growth in their town [11].

Consistent with previous research, the relationships between the place attachment dimensions and perceived positive impacts of tourism were found to be mostly significant, except for place dependence and environmental impacts. While place identity was found to have a significant impact on all three dimensions of positive impacts (economic, socio-cultural, and environmental), place dependence was found to have a significant impact on two dimensions (economic and socio-cultural). Residents who believe their town has a higher level of positive economic impact are more likely to appreciate it [5]. According to some scholars, citizens’ views of economic impacts affect their community connection [5,56,84]. People who are concerned about their town are more likely to see tourism as providing economic and cultural advantages to their community [56]. The type and strength of inhabitants’ place identification, as well as their attachment to the environment and surrounding landscape, may be crucial factors in effective cohabitation between residents and the tourist sector [84,85]. Positive impacts were also obtained between place attachment dimensions and support for tourism. As Ganji et al. [9] state, higher levels of community attachment among inhabitants resulted in a more favorable attitude toward tourism development. This shows that residents who are more devoted to the community are more inclined to support tourism development in places with intense tourism growth [69]. In addition to the above, this research confirmed two of the six assumed connections between place attachment dimensions and perceived negative influences of tourism. Such results are in line with other studies that state that residents have a stronger perception of tourism’s positive impacts compared to negative impacts [21,56]. Place dependence has a negative effect on negative economic impacts, while place identity has a negative effect on negative environmental impacts. People who care more about negative environmental effects are less likely to feel dedicated to or proud of their town. Residents may be concerned about the direct effects on their lives and communities, as tourist destinations are places where future generations will continue to dwell [86].

The findings, in particular, demonstrated favorable significant connections between all three dimensions of perceived positive impacts and support for tourism.

According to the findings, a more favorable perception of economic impacts leads to stronger support for future growth. This reflects the widespread perception of tourism as a tool for local economic development [15,18,24,87]. Similarly, the more positively citizens see its socio-cultural benefits, the more inclined they are to support tourism growth, which is in line with other studies [17,24,33]. Hypotheses H8C and H9C were also confirmed, which shows that the more (or less) the more favorable the population estimates the ecological consequences of tourism to be, the more (or less) they support development [24]. The findings show that when people believe that the beneficial effects of tourism are likely to outweigh the negative aspects, they are more likely to accept exchanges and, as a result, support tourism growth in their city, as confirmed by other research [21,56,70]. As is evident for Novi Sad, perceived socio-cultural impacts have the strongest effect, followed by economic and environmental impacts. This is not completely unexpected considering that, since 2018, great events have been held in Novi Sad—“Doček” (Welcome), two New Year’s Eve celebrations, and the Kaleidoscope of Culture, which should remain as the cultural legacy of the city and continue to be held after 2022. It is estimated that starting from 2017 until the end of 2022, over 5400 artists will participate in the programs. Thanks to these legacy projects for which the capital became famous, even before the title year in November 2021, Novi Sad received the award for the best European trend brand, which is awarded in Dresden. Thus, Novi Sad joined European metropolises such as Paris, Amsterdam, London, Oslo and Munich [88].

Finally, during the preparations for the European Capital of Culture, the first concert hall in the city’s history was built, which after almost 100 years became home to the Music and Ballet School, thus creating a unique model of synergy between the two institutions.

The major novelty of this study resides in the analysis of the effects of cultural involvement and place attachment on residents’ perceptions of tourism’s positive and negative impacts, and on the residents’ attitudes of support for tourism development. This study contributes to the current literature mainly as the first study to test such a complex model, encompassing mentioned relationships in one single model and a new study context. The study proposes a research instrument to ascertain these aspects, which other researchers may use to examine local inhabitants’ impressions of tourism in other geographical locations, particularly in urban areas. Furthermore, this is also the first study to test and confirm the influence of residents’ cultural involvement on place attachment. Moreover, this study, apart from confirming some relationships which have already been tested in the previous literature, also reveals some new results, especially regarding place attachment’s negative effect on negative economic and environmental impacts.

Further, this study provides tourism planners with useful information about residents’ opinions, assessments of the effects of tourism, and encouragement for the growth of tourism. These insights may be used by urban planners and developers to create communication strategies that address specific challenges presented by each group of respondents. This may assist them in acquiring more support, and may raise the likelihood of tourism development. These communication strategies may refer to communications with residents through various types of promotion of cultural events, and through highlighting the cultural investments and new projects in the city (especially due to receiving the EPK title). Moreover, as the perception of negative environmental impacts was the only factor to negatively affect support for tourism development, the communication should be directed towards the authorities (communal enterprises, the city council, the department for urbanism, etc.) on reducing/overcoming these causes in order to increase the residents’ tourism support. Foundation Novi Sad European Capital of Culture 2022 should communicate the importance of tourism for the development of the local community through various forms of promotion and advertising through various media—social networks, radio, and TV shows, etc. Communication strategies should also include certain educational programmes in order to familiarize residents with the importance of tourism for the development of the local community, and to strengthen their support for the city’s tourism development.

6. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

There are a few limitations of the study that should be pointed out. Firstly, the generalizability of the results is limited, as the data were collected through a convenient method. Some more precise findings could be obtained by using a stratified sample. Secondly, we only considered the effect of cultural involvement on place attachment, perceived tourism impacts, and support for tourism development. Some variables, such as cultural attitudes [12], can be considered as potential predictors. Furthermore, this study considered two dimensions of place attachment—place identity and place dependence. There are also other moderator factors to consider, such as socio-demographic data. Citizens working in the tourist sector, for example, may view the value of tourism more favorably and have a stronger tendency to support it than people who do not work in the sector. Another interesting topic the future research should address is the analysis of the changes brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic on place attachment, cultural involvement, and residents’ attitudes towards tourism development. Finally, the future research should put more emphasis on implicit measures of residents’ attitudes and impacts, as this could provide more accurate and sincere data.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su14159103/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B., T.P., S.K. and M.C.; methodology, I.B. and T.P.; formal analysis, I.B. and T.P.; investigation, M.B.Ž., T.L., B.Đ. and D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, T.P., I.B., S.K. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, B.Đ. and D.B.; visualization, M.B.Ž. and T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Provincial Secretariat for Higher Education and Scientific Research of the Vojvodina Province, Serbia, as the part of the project numbered 142-451-2615/2021-01/1.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a part of the project number 142-451-2615/2021-01/1, funded by the Provincial Secretariat for Higher Education and Scientific Research of the Vojvodina Province, Serbia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, C. Catalyst or barrier? The influence of place attachment on perceived community resilience in tourism destinations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tovar, C.; Lockwood, M. Social impacts of tourism: An Australian regional case study. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-García, F.; Peláez-Fernández, M.A.; Balbuena-Vazquez, M.; Cortés-Macias, R. Residents’ perceptions of tourism development in Benalmádena (Spain). Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rasoolimanesh, M.; Jaafar, M.; Kock, N.; Ahmad, G. The effects of community factors on residents’ perceptions toward World Heritage Site inscription and sustainable tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adongo, R.; Choe, J.C.; Han, H. Tourism in Hoi An, Vietnam: Impacts, perceived benefits, community attachment and support for tourism development. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2017, 17, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D. The role of place image dimensions in residents’ support for tourism development. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eusébio, C.; Vieira, A.L.; Lima, S. Place attachment, host–tourist interactions, and residents’ attitudes towards tourism development: The case of Boa Vista Island in Cape Verde. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 890–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.L.; Feng, X. Residents’ sense of place, involvement, attitude, and support for tourism: A case study of Daming Palace, a Cultural World Heritage Site. Asian Geogr. 2020, 37, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganji, S.F.G.; Johnson, L.W.; Sadeghian, S. The effect of place image and place attachment on residents’ perceived value and support for tourism development. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rua, S.V. Perceptions of tourism: A study of residents’ attitudes towards tourism in the city of Girona. J. Tour. Anal. Rev. De Análisis Turístico 2020, 27, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pan, L.; Hu, Y. Cultural involvement and attitudes toward tourism: Examining serial mediation effects of residents’ spiritual wellbeing and place attachment. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, M.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Taheri, B. Assessing the mediating role of residents’ perceptions toward tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, S.; Vujičić, D.M.; Čikić, J.; Šagovnović, I.; Stankov, U.; Zelenović Vasiljević, T. Impact of the European Capital of Culture Project on the Image of the City of Novi Sad—The Perception of the Local Community. Turizam 2021, 25, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šagovnović, I.; Pivac, T.; Kovačić, S. Examining antecedents of residents’ support for the European Capital of Culture project—event’s sustainability perception, emotional solidarity, community attachment and brand trust. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2022, 13, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Nunkoo, R.; Alders, T. London residents’ support for the2012 Olympic Games: The mediating effect of overall attitude. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.P. Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 665–690. [Google Scholar]

- Jurowski, C.; Uysal, M.; Williams, D.R. A theoretical analysis of host community resident reactions to tourism. J. Travel Res. 1997, 36, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Jurowski, C.; Uysal, M. Resident attitudes: A structural modeling approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pfister, R. Residents’ attitudes toward tourism and perceived personal benefits in a rural community. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Murray, I. Resident attitudes toward sustainable community tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, J. The influence of place identity on perceived tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Residents support for tourism: An identity perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkisoon, H. Developing a community support model for tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 964–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Biran, A.; Sit, J.; Szivas, E.M. Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceive tourism impacts. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M.; Kock, N.; Ramayah, T. A revised framework of social exchange theory to investigate the factors influencing residents’ perceptions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E.T.; Bosley, H.E.; Dronberger, M.G. Comparisons of stakeholder perceptions of tourism impacts in rural eastern North Carolina. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jiang, J.; Xu, S.; Guo, Y. Community participation and residents’ support for tourism development in ancient villages: The mediating role of perceptions of conflicts in the tourism community. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Uriely, N.; Reichel, A. The intensity of tourist-host social relationship and its effects on satisfaction and change of attitudes: The case of working tourists in Israel. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Nunkoo, R. City Image and Perceived Tourism Impact: Evidence from Port Louis. Mauritius. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2011, 12, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Geng, C.; Su, X. Antecedents of residents’ pro-tourism behavioral intention: Place image, place attachment, and attitude. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Ferguson, J. (Eds.) Culture, Power, Place: Explorations in Critical Anthropology; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 1997; p. 357. [Google Scholar]

- Rapacciuolo, A.; Perrone Filardi, P.; Cuomo, R.; Mauriello, V.; Quarto, M.; Kisslinger, A.; Savarese, G.; Illario, M.; Tramontano, D. The impact of social and cultural engagement and dieting on well-being and resilience in a group of residents in the metropolitan area of Naples. J. Aging Res. 2016, 2016, 4768420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spennemann, D.H. The Nexus between Cultural Heritage Management and the Mental Health of Urban Communities. Land 2022, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Xu, X.; Lu, L.; Gursoy, D. How cultural confidence affects local residents’ wellbeing. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 41, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernandez, B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Investigating the Effect of Festival Visitors’ Emotional Experiences on Satisfaction, Psychological Commitment, and Loyalty. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Backlund, E.A.; Williams, D.R. A quantitative synthesis of place attachment research: Investigating past experience and place attachment. In Paper Presented at the Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium; Bolton Landing: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, M.J.; Brown, G. Tourism experiences in a lifestyle destination setting: The roles of involvement and place attachment. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.D.; Brown, G.; Kim, A.K.J. Measuring resident place attachment in a World Cultural Heritage tourism context: The case of Hoi An (Vietnam). Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2059–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Raymond, C. The relationship between place attachment and landscape values: Toward mapping place attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2007, 27, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Brown, G.; Weber, D. The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Dwyer, L.; Firth, T. Effect of dimensions of place attachment on residents’ word-of-mouth behavior. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 826–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar]

- White, D.D.; Virden, R.J.; Van Riper, C.J. Effects of place identity, place dependence, and experience-use history on perceptions of recreation impacts in a natural setting. Environ. Manag. 2008, 42, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispas, A.; Untaru, E.N.; Candrea, A.N.; Han, H. Impact of Place Identity and Place Dependence on Satisfaction and Loyalty toward Black Sea Coastal Destinations: The Role of Visitation Frequency. Coast. Manag. 2021, 49, 250–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; Strzelecka, M.; Yeager, E.P.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Aleshinloye, K.D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Mimbs, B.P. Measuring place attachment with the Abbreviated Place Attachment Scale (APAS). J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 74, 101577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Roggenbuck, J.W. Measuring place attachment: Some preliminary results. In Proceedings of the Paper Presented at the NRPA Symposium on Leisure Research, San Antonio, TX, USA, 20–22 October 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R.; Patterson, M.E.; Roggenbuck, J.W.; Watson, A.E. Beyond the commodity metaphor: Examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Census of Population, Households, and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia. 2011. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.rs/en-us/oblasti/popis/popis-2011/ (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Besculides, A.; Lee, M.E.; McCormick, P.J. Residents’ perceptions of the cultural benefits of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 29, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.S. How recreation involvement, place attachment and conservation commitment affect environmentally responsible behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-Garcia, M.-A.; Castellanos-Verdug, M.; Martin-Ruiz, D. Gaining resident’s support for tourism and planning. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.R.; Hafer, H.R.; Long, P.; Perdue, R. Rural residents’ attitudes toward recreation and tourism development. J. Travel Res. 1993, 31, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, P.; Cheyne, J. Residents’ attitudes to proposed tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 27, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Rutherford, D.G. Host attitudes toward tourism: An improved structural model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, R.R.; Long, P.T.; Allen, L. Resident support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.P. Residents’ perceptions research on the social impacts of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 610–616. [Google Scholar]

- Lankford, S.V.; Howard, D.R. Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J.; Crompton, J.L. Developing and testing a tourism impact scale. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunt, P.; Courtney, P. Host perceptions of sociocultural impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 493–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, A.J.; Snaith, T.; Miller, G. The social impacts of tourism: A case study of Bath, UK. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 647–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomljenovic, R.; Faulkner, B. Tourism and older residents in a Sunbelt Resort. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 27, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Gursoy, D.; Chen, J.S. Validating a tourism development theory with structural equation modeling. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.C.; Var, T. Resident attitudes toward tourism impacts in Hawaii. Ann. Tour. Res. 1986, 13, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akis, S.; Peristianis, N.; Warner, J. Residents’ attitudes to tourism development: The case of Cyprus. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northcote, J.; Macbeth, J. Limitations of resident perceptions surveys for understanding tourism social impacts: The need for triangulation. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 30, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, A.; Pizam, A. Social impacts of tourism on Central Florida. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A. Tourism’s impacts: The social costs to the destination community as perceived by its residents. J. Travel Res. 1978, 16, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.; Kayat, K. Residents’ perceptions of tourism impact and their support for tourism development: The case study of Cuc Phuong National Park, Ninh Binh province, Vietnam. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 4, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, W.T.S.; Tung, V.W.S. Assessing explicit and implicit stereotypes in tourism: Self-reports and implicit association test. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.; Tung, V.W.S. Residents’ discrimination against tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 88, 103060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Application Form, Novi Sad 2021. Available online: https://novisad2022.rs/en/documents/ (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Gu, M.; Wong, P.P. Residents’ perception of tourism impacts: A case study of homestay operators in Dachangshan Dao, North-East China. Tour. Geogr. 2006, 8, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Dyer, P. A longitudinal study of the residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts using data from the sunshine coast Australia. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2012, 10, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Pan, L.; Del Chiappa, G. Examining destination personality: Its antecedents and outcomes. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; So, K.K.F. Residents’ support for tourism: Testing alternative structural models. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beaujean, A.A. Latent Variable Modeling Using R: A Step-by-Step Guide; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, D.R.; McDonald, C.D.; Riden, C.M.; Uysal, M. Community attachment, regional identity and resident attitudes towards tourism. In 26th Annual Travel and Tourism Research Association Conference Proceedings; Travel and Tourism Research Association: Wheat Ridge, CO, USA, 1995; pp. 424–428. [Google Scholar]

- McCool, S.F.; Martin, S.R. Community attachment and attitudes toward tourism development. J. Travel Res. 1994, 32, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Fletcher, J.; Fyall, A.; Gilbert, D.; Wanhill, S. Tourism: Principles and Practice, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: Essex, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://novisad2022.rs (accessed on 15 May 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).