The Role of the Cultural and Creative Industries in Sustainable Development of Small Cities in Latvia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background, Research Question, and Purposes

1.2. What Are Cultural and Creative Industries?

1.3. What Is Sustainable Development of a Small City and Its Challenges?

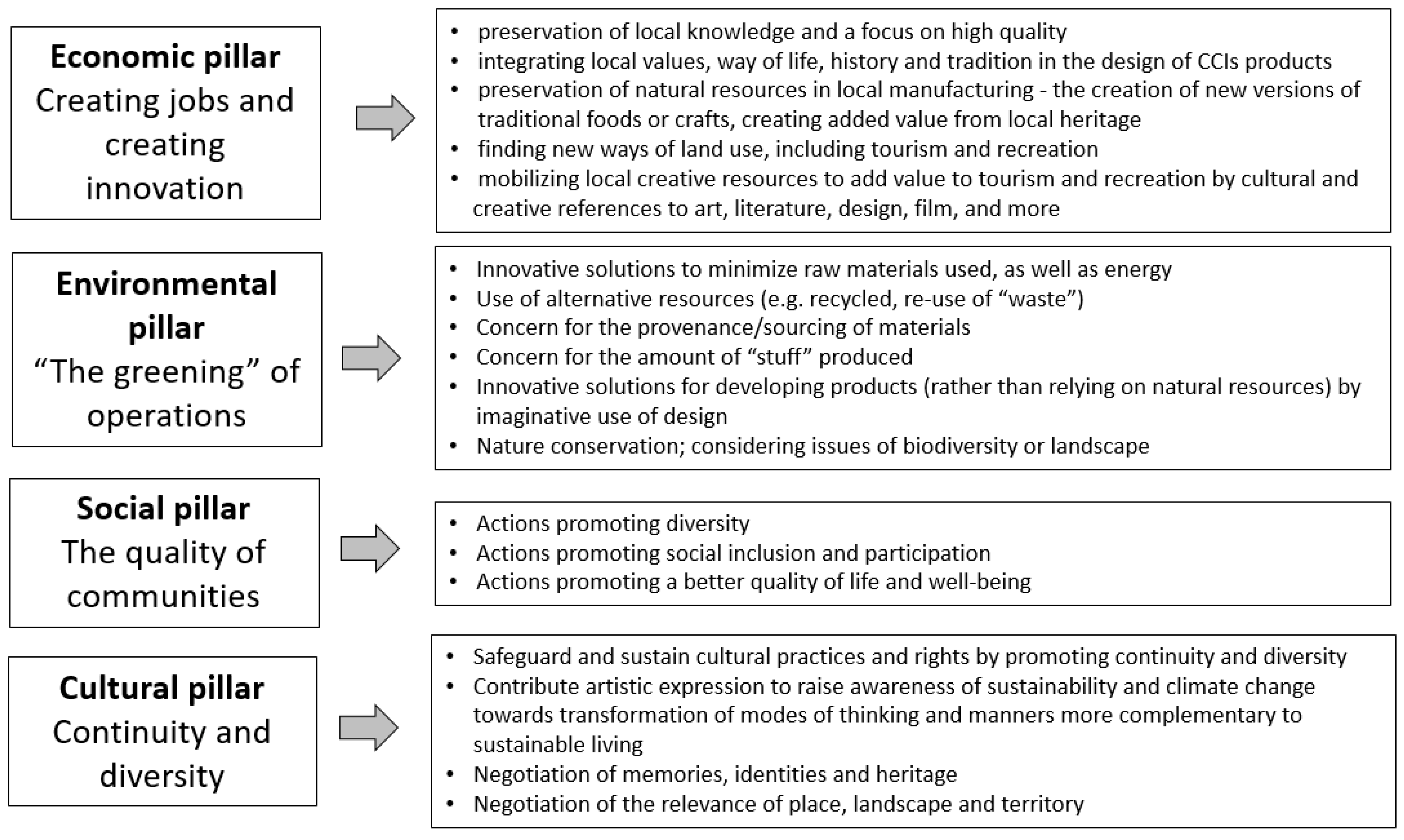

1.4. The Role of CCIs in Sustainable Development

2. Research Methods

- Riga is the capital city of the Republic of Latvia;

- Cities of the Republic of Latvia are divided into State cities and municipality towns;

- The State cities are Daugavpils, Jelgava, Jekabpils, Jurmala, Liepaja, Ogre, Rezekne, Riga, Valmiera, and Ventspils;

- Towns are determined in Annex to the Law, and according to the Annex, Cēsis is the administrative center of Cēsis municipality. There are two towns in Cēsis municipality: the town of Cēsis and the town of Ligatne.

- As an entrepreneur, are you interested in promoting the sustainable development of Cēsis city (municipality)?

- Do you believe that your company contributes to the sustainable development of Cēsis city (municipality)?

- Candle making;

- Sports and recreation;

- Linen product making;

- Recreation complex and event venue;

- A small porcelain factory.

3. Results

- There are not enough local resources in the municipality;

- I am not satisfied with the quality-price ratio of local resources.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Green Paper—Unlocking the Potential of Cultural and Creative Industries. 2010. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/1cb6f484-074b-4913-87b3-344ccf020eef/language-en (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- European Commission a New European Agenda for Culture. 2018. Available online: https://culture.ec.europa.eu/document/new-european-agenda-culture-swd2018-267-final (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Hall, K.J.; Daneke, G.A.; Lenox, M.J. Sustainable development and entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selada, C.; da Cunha, I.V.; Tomaz, E. Creative-based strategies in small and medium-sized cities: Key dimensions of analysis. Quaest. Geogr. 2012, 31, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collins, P.; Mahon, M.; Murtagh, A. Creative industries and the creative economy of the West of Ireland: Evidence of sustainable change? Creat. Ind. J. 2018, 11, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, J. Community resources for small city creativity? Rethinking creative economy narratives at the Blue Mountains Music Festival. Aust. Geogr. 2018, 49, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INTELI. Creative-Based Strategies in Small and Medium Sized Cities: Guidelines for Local Authorities. Final Output of the URBACT Project “Creative Clusters in Urban Areas of Low Density”. INTELI Technical Action Plan. 2011. Available online: https://urbact.eu/sites/default/files/import/Projects/Creative_Clusters/documents_media/URBACTCreativeClusters_TAP_INTELI_Final_01.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Luckman, S. Craft entrepreneurialism and sustainable scale: Resistance to and disavowal of the creative industries as champions of capitalist growth. Cult. Trends 2018, 27, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, K.; Ward, J. The art of the good life: Culture and sustainable prosperity. Cult. Trends 2018, 27, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, A.D.; Wojan, R.T.; Lambert, D.M. The rural growth trifecta: Outdoor amenities, creative class and entrepreneurial context. J. Econ. Geogr. 2011, 11, 529–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, A.J. Cultural-Products Industries and Urban Economic Development: Prospects for Growth and Market contestation in Global Context. Urban Aff. Rev. 2004, 39, 461–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A.; Cameron, G. Voices of Culture: The Role of Culture in Non-Urban Areas of the European Union; Goethe-Institut: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://voicesofculture.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/VoC-Brainstorming-Report-Role-of-Culture-in-Non-Urban-Areas-of-the-EU.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Wojan, T.R.; Nicols, B. Design, innovation, and rural creative places: Are the arts the cherry on top, or the secret sauce? PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kerrigan, S.; Hutchinson, S. Regional Creative Industries: Transforming the Steel City into a Creative City in Newcastle, Australia. Creat. Ind. J. 2016, 9, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, N. Cultural and creative work in rural and remote areas: An emerging international conversation. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2020, 27, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckman, S. Locating Cultural Work: The Politics and Poetics of Rural, Regional and Remote Creativity, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1349347117. [Google Scholar]

- Kunda, I.; Tjarve, B.; Eglīte, Ž. Creative Industries in Small Cities: Contributions to Sustainability. In Economic Science for Rural Development, Proceedings of the 22nd International Scientific Conference, Jelgava, Latvia, 11–14 May 2021; LLU: Jelgava, Latvia, 2021; Volume 55, pp. 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towse, R. Cultural economics, copyright and the cultural industries. Soc. Econ. Cent. East. Eur. 2000, 22, 107–134. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41468494 (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Caves, R.E. Creative Industries: Contracts between Art and Commerce, 1st ed.; Harvard University Press: London, UK, 2000; pp. 47–49. ISBN 0-674-00164-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, S. From cultural to creative industries, theory, industry and policy implications. Media Int. Aust. 2002, 102, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, S. Creative Industries as a Globally Contestable Policy Field. Chin. J. Commun. 2009, 2, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flew, T. Beyond Ad Hocery: Defining Creative Industries. Presented at Cultural Sites, Cultural Theory, Cultural Policy. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Cultural Policy Research (ICCPR), Wellington, New Zealand, 23–26 January 2002; Available online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/256/ (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Hesmondhalgh, D. The Cultural Industries; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 9780761954521. [Google Scholar]

- Caust, J. Putting the “art” back into arts policy making: How arts policy has been “captured” by the economists and the marketers. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2003, 9, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesmondhalgh, D.; Pratt, A.C. Cultural industries and cultural policy. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2005, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oakley, K.; O’Connor, J. The Cultural Industries: An Introduction from Culture to Creativity—And Back Again? In Routledge Companion to the Cultural Industries, 1st ed.; Oakley, K., O’Connor, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; Available online: http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/205962/4/205962.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Defillippi, R.; Grabher, G.; Jones, C. Introduction to Paradoxes of Creativity: Managerial and Organizational Challenges in the Cultural Economy. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Fraser, I.; Fillis, I. Creative futures for new contemporary artists: Opportunities and barriers. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2018, 20, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kunda, I.; Zemīte, I.; Laķe, A. Cultural Entrepreneurship: Negotiating Paradoxes in New Cultural Product Development. Int. J. Interdiscip. Cult. Stud. 2021, 16, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, A.; Heinze, A. Entrepreneurship in the Cultural and Creative Industries: Insights from an Emergent Field. A J. Entrep. Arts 2016, 5, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, G.; Cimattia, B.; Melosia, F. A Proposal for the Evaluation of Craftsmanship in Industry. In Procedia CIRP, Proceedings of the 13th Global Conference on Sustainable Manufacturing—Decoupling Growth from Resource Use, Ho Chi Minh City Binh Duong, Vietnam, 16–18 September 2015; Seliger, G., Kohl, H., Mallon, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 40, pp. 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Throsby, D. Economic and Culture; Cambrige University Press: Cambrige, UK, 2001; ISBN 978-0521586399. [Google Scholar]

- Klamer, A. Doing the Right Thing: A Value Based Economy; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-909188-92-1. [Google Scholar]

- Towse, R. Human Capital and Artists’ Labour Markets. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture, 1st ed.; Ginsburgh, V.A., Throsby, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 865–892. ISBN 0-444-50870-8. [Google Scholar]

- WIPO. World Intellectual Property Indicators 2020. Geneva: World Intellectual Property Organization. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_941_2020.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Daubeuf, C.; Pratt, A.; Airaghi, E.; Pletosu, T. Enumerating the Role of Incentives in CCI Production Chains. (CICERONE Report D3.2). Zenodo. 2020. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4015932 (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor. Available online: https://composite-indicators.jrc.ec.europa.eu/cultural-creative-cities-monitor (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Bonifacio, G.T.; Drolet, J.L. Introduction. In Canadian Perspectives on Immigration in Small Cities; Bonifacio, G.T., Drolet, J.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; p. 5. ISBN 978-3-319-40423-3. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlić, M.; Vojković, L.; Vojković, G. Small City Like Smart City—Proposal for Town of VIS. In Proceedings of the 26th Geographic Information Systems Conference and Exhibition “GIS ODYSSEY 2019”, Split, Croatia, 2–6 September 2019; pp. 199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Zainudin, N.; Lau, J.L.; Munusami, C. Micro-Macro. Measurements of Sustainability. In Affordable and Clean Energy. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikdar, S.K. Macro, Meso & Micro Aspects of Sustainability. In Proceedings of the Tardis Workshop, Estes Park, CO, USA, 3–4 June 2014; Available online: http://tardis.tugraz.at/wiki/lib/exe/fetch.php?media=tardis2014_18_sikdar.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- Viswanathan, M.; Jung, K.; Venugopal, S.; Minefee, I.; Jung, I.W. Subsistence and Sustainability: From Micro-Level Behavioral Insights to Macro-Level Implications on Consumption, Conservation, and the Environment. J. Macromarketing 2014, 34, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, K.; Dessein, J. Culture-Sustainability Relation: Towards a Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duxbury, N.; Kangas, A.; de Beukelaer, C. Cultural policies for sustainable development: Four strategic paths. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2017, 23, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojnik, J.; Ruzzier, M.; Konecnik Ruzzier, M. Transition towards Sustainability: Adoption of Eco-Products among Consumers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CHCfE Consortium. Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe. 2015. Available online: http://blogs.encatc.org/culturalheritagecountsforeurope//wp-content/uploads/2015/06/CHCfE_FULL-REPORT_v2.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Dessein, J.; Soini, K.; Fairclough, G.; Horlings, L. (Eds.) Culture in, for and as Sustainable Development. Conclusions from the COST Action IS1007 Investigating Cultural Sustainability; University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2015; ISBN 978-951-39-6177-0. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Černevičiūtė, J.Ū.; Strazdas, R.; Kregždaitė, R.E.; Tvaronavičienė, M. Cultural and creative industries for sustainable postindustrial regional development: The case of Lithuania. J. Int. Stud. 2019, 12, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, E.; Townsend, L. The Contribution of the Creative Economy to the Resilience of Rural Communities: Exploring Cultural and Digital Capital. Sociol. Rural. 2015, 56, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, R.; Miller, T. Greening cultural policy. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2017, 23, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikmane, E.; Lake, A. Critical Review of Sustainability Priorities in the Heritage Sector: Evidence from Latvia’s Most Visited Museums. Eur. Integr. Stud. 2021, 15, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4129-6099-1. [Google Scholar]

- Walliman, N. Social Research Methods; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 9781412910620. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L. Research Methods in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; ISBN 978-0415102353. [Google Scholar]

- Kroplijs, A.; Raščevska, M. Kvalitatīvās Pētniecības Metodes Sociālajās Zinātnēs; Izdevniecība RaKa: Riga, Latvia, 2010; ISBN 9789984461410. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valtenbergs, V.; Fermin, A.; Grisel, M.; Servillo, L.; Vilka, I.; Livina, A.; Berzkalne, L. Challenges of Small and Medium-Sized Urban Areas (SMUAs), Their Economic Growth Potential and Impact on Territorial Development in the European Union and Latvia. Available online: https://www.varam.gov.lv/sites/varam/files/final_report_4.3.-24_nfi_inp-002_.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Law on Administrative Territories and Populated Areas. Entered into Force on 23 June 2020. Available online: https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/315654 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Official Statistics Portal—Official statistics of Latvia. Available online: https://stat.gov.lv/en (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- British Council Mapping the Creative Industries: A Toolkit. 2010. Available online: https://creativeconomy.britishcouncil.org/media/uploads/files/English_mapping_the_creative_industries_a_toolkit_2-2.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Lazzeretti, L.; Boix, R.; Capone, F. On the Concentration of Creative Industries in Specialized Creative Local Production Systems in Italy and Spain: Patterns and Determinants. EUNIP 2010. In Proceedings of the European Network on Industrial Policy International Conference, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Faculty of Economics, Reus, Spain, 9–11 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Malmqvist, J.; Hellberg, K.; Mollas, G.; Rose, R.; Shevlin, M. Conducting the Pilot Study: A Neglected Part of the Research Process? Methodological Findings Supporting the Importance of Piloting in Qualitative Research Studies. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- In, J. Introduction of a pilot study. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2017, 70, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Teijlingen, E.R.; Hundley, V. The importance of pilot studies. Soc. Res. Update 2001, 35. Available online: https://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU35.html (accessed on 8 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Ghazaly, N.H. A Reliability and Validity of an Instrument to Evaluate the School-Based Assessment System: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. (IJERE) 2016, 5, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzog, M.A. Considerations in Determining Sample Size for Pilot Studies. Res. Nurs. Health 2008, 31, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, J.; Fahlman, D.; Arscott, J.; Guillot, I. Pilot Testing for Feasibility in a Study of Student Retention and Attrition in Online Undergraduate Programs. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2018, 19, 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, S.; Michael, W.B. Handbook in Research and Evaluation, 3rd ed.; EdITS: San Diego, CA, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0912736327. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, R. What sample size is “enough” in internet survey research? Interpers. Comput. Technol. Electron. J. 1998, 6, pp. 1–10. Available online: http://cadcommunity.pbworks.com/f/what%20sample%20size.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2021).

- Givens, S.E.; Musil, C.M. Pilot Study. In Encyclopedia of Nursing Research, 4th ed.; Fitzpatrick, J.J., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 9780826133045. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.C.; Whitehead, A.L.; Jacques, R.M.; Julious, S.A. The statistical interpretation of pilot trials: Should significance thresholds be reconsidered? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doody, O.; Doody, C.M. Conducting a pilot study: Case study of a novice researcher. Br. J. Nurs. 2015, 24, 1074–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blythe LaGasse, A. Pilot and feasibility studies: Application in music therapy research. J. Music Ther. 2013, 50, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morgan, D.L.; Krueger, R.A. The Focus Group Kit, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0761907602. [Google Scholar]

- Lindlof, T.R.; Taylor, B.C. Qualitative Communication Research Methods, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; ISBN 0-7619-2494-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cities, Culture, Creativity: Leveraging Culture and Creativity for Sustainable Urban Development and Inclusive Growth. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2021. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377427 (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Commission staff working document - Accompanying document to the Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on a European agenda for culture in a globalizing world - Inventory of Community actions in the field of culture COM (2007) 242 final 2007. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/9ee27c14-8399-46af-a784-d7bd40ca532e/language-mt (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Alvedalen, J.; Boschma, R. A critical review of entrepreneurial ecosystems research: Towards a future research agenda. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 887–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boorsma, M. A strategic logic for arts marketing: Integrating customer value and artistic objectives. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2006, 12, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, P.A. Strategic Entrepreneurship, 4th ed.; Perason Education Limited: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0273706427. [Google Scholar]

- Tol, R.J.J. The Economic Impacts of Climate Change. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2018, 12, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tilley, F.; Young, W. Sustainability Entrepreneurs: Could They Be the True Wealth Generators of the Future? Greener Manag. Int. 2009, 55, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ngwakwe, C. Sustainable Product Innovation and Consumer Demand in EU Market for Sustainable Products. Acta Univ. Danubius. Œconomica 2020, 16, 32–42. Available online: https://dj.univ-danubius.ro/index.php/AUDOE/article/view/407 (accessed on 25 October 2021).

| Research Questions | Methods Employed | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| RQ1: Is there an interrelation between CCIs and the four pillars of sustainability in small cities? RQ2: What are the practices that CCIs use and which may be considered contributions to sustainability? | Content analysis (of mass media publications on CCIs in Cēsis County) n = 517 | Tentatively identify CCI initiatives/businesses whose actions correspond to the theoretically derived typology (Figure 1) as an entry point for the use of other methods. (RQ2) |

| A pilot survey (of CCI entrepreneurs) 30% of total sample size | Identify numerical values of perceived overall CCI contribution to sustainability, and the frequency of practices corresponding to the theoretically derived typology (Figure 1). (RQ1, RQ2) | |

| Semi-structured qualitative interviews with CCI entrepreneurs n = 21 | Get deeper into CCI informants’ perceptions of the various sustainability-related practices carried out and identify their correspondence to the theoretically derived typology (Figure 1). (RQ1, RQ2) | |

| Focus group discussion with CCI entrepreneurs | Get deeper into informants’ perceptions of the various sustainability-related practices carried out and identify their correspondence to the theoretically derived typology (Figure 1); expand on the pilot survey data. (RQ1, RQ2) |

| Indicators | Cēsis Municipality | Cēsis City |

|---|---|---|

| Population (beginning of 2021) | 41,161 | 14,815 |

| Territory (km2) | 2668.13 | 19.28 |

| Economically active enterprises of CCIs (2019) | 198 | … |

| Share of CCIs (% of all enterprises) | 5 | … |

| NACE | Economic Activity |

|---|---|

| C15 | Manufacture of leather and related products |

| C16 | Manufacture of wood and of products of wood and cork, except furniture, manufacture of articles of straw and plaiting materials |

| C18 | Printing and reproduction of recorded media |

| C31 | Manufacture of furniture |

| J58 | Publishing activities |

| J59 | Motion picture, video and television program production, sound recording and music publishing activities |

| J60 | Programming and broadcasting activities |

| M71 | Architectural and engineering activities, technical testing and analysis |

| M73 | Advertising and market research |

| N79 | Travel agency, tour operator and other reservation service and related activities |

| R90 | Creative, arts and entertainment activities |

| R91 | Libraries, archives, museums and other cultural activities |

| R93 | Sports activities and amusement and recreation activities |

| Questions and Answers | Relative Weights (α) | Total Points (TP) | Final Points (FP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Do You use local resources in Your business? | 2.87 | ||

| Yes (P = 5) | 0.20 | 2.64 | |

| Partly ( P = 3) | 0.55 | ||

| No (P = 0) | 0.25 | ||

| 2. Do You produce product with high value added? | |||

| Yes (P = 5) | 0.52 | 3.39 | |

| Partly (P = 3) | 0.26 | ||

| No (P = 0) | 0.22 | ||

| 3. Do You export Your products? | |||

| Yes (P = 5) | 0.44 | 2.59 | |

| Partly (P = 3) | 0.13 | ||

| No (P = 0) | 0.43 | ||

| Thematic Group of the Questions | Questions |

|---|---|

| Introduction—the purpose of the research and the use of the results | The focus group discussion is conducted within a study whose aim is to analyze the perceived contribution of creative industries to sustainable development of small cities. The focus of the research is Cēsis municipality. Your views will provide an opportunity to assess the contribution and trade-offs of sustainability in the creative industries. |

| Understanding sustainability |

|

| Environmental sustainability |

|

| Social sustainability |

|

| Cultural sustainability |

|

| Economic sustainability and trade-offs |

|

| Practices | Ec | En | Cul | Soc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creating a DIY style interior: furniture refurbished, recycled, upcycled, usability changed | x | x | ||

| Creating products that promote child development | x | x | ||

| Relocating a factory to reduce the long driving hours for employees, allowing more time together with their family | x | x | ||

| Creating a cozy environment, a home-like feeling | x | x | ||

| Creating a platform (a physical pop-up store) to promote the sales of local craftsperson products, providing a space with a DJ, artworks, paintings | x | x | x | |

| Producing premium segment solid wood chairs, requiring high-quality handiwork | x | x | ||

| Producing environmentally friendly garden furniture by using PET bottle caps, with innovative technology of production – each part having its own unique pattern | x | x | ||

| Providing a platform for the content of a conference to world—wide audiences | x | x | ||

| Producing more than a thousand different products, part subcontracted to small companies | x | |||

| Creating new products from carrot pomace mixed with other vegetables, seeds | x | x | ||

| Reusing paper boxes, packaging material for shipping | x | x | ||

| Creating eco pockets for dresses from fabric waste | x | x | ||

| Creating products with a symbolic motif of the place | x | x | ||

| Appreciating co-creation as a possibility of development | x | x | ||

| (Company) acting as a cultural ambassador of the region | x | x | ||

| Providing cultural supply (concerts, events, activities) free of charge for the locals | x | x | ||

| Appreciating community as a value | x | x | ||

| Cooperating with neighbors | x | x | ||

| Organizing thank-you concerts just for employees | x | x | ||

| Providing lunch for employees free of charge | x | x | ||

| Engaging a person with a functional disability to answer phone calls (physical distance 200 km) | x | |||

| Engaging school children to do service work and training them | x | x | ||

| Organizing a zero waste production process | x | x | ||

| Sorting waste and encouraging others to do so on site | x | |||

| Opening a Mini Zoo, animals fed by the company’s customers’ uneaten food | x | x | ||

| Using surpluses of materials for creative workshops for the locals | x | |||

| Giving access to surpluses of materials for personal use | x | |||

| Appreciating products as storytellers of the local history | x | x | ||

| Getting an inspiration from local cultural heritage to create dresses | x | x | ||

| Opening a local craftspersons’ shop | x | x | ||

| Appreciating the history of the place as a resource for tourism | x | x | ||

| Appreciating geographic location as a resource for tourism | x | x |

| Questions | Answers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| It Is Difficult to Answer | No | Yes | ||||

| Average value = 4.75 | |||||

| Average value = 4.25 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zemite, I.; Kunda, I.; Judrupa, I. The Role of the Cultural and Creative Industries in Sustainable Development of Small Cities in Latvia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159009

Zemite I, Kunda I, Judrupa I. The Role of the Cultural and Creative Industries in Sustainable Development of Small Cities in Latvia. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159009

Chicago/Turabian StyleZemite, Ieva, Ilona Kunda, and Ilze Judrupa. 2022. "The Role of the Cultural and Creative Industries in Sustainable Development of Small Cities in Latvia" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159009

APA StyleZemite, I., Kunda, I., & Judrupa, I. (2022). The Role of the Cultural and Creative Industries in Sustainable Development of Small Cities in Latvia. Sustainability, 14(15), 9009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159009