Abstract

It is well-acknowledged that organizational sustainability largely depends on employees’ innovative behavior, which is the same case with higher education institutions. This study aimed to explore the characteristics of and relationships between faculty members’ mastery goals and innovative behavior under the framework of achievement goal theory in the research context. Results from an anonymous questionnaire survey of 621 Chinese faculty members revealed a four-dimensional structure of mastery goals (task-approach goals, task-avoidance goals, learning-approach goals, and learning-avoidance goals) and a five-dimensional structure of innovative research behavior (opportunity exploration, generativity, formative investigation, championing, and application). The faculty members reported a high level of mastery goals for research and a moderate level of innovative research behavior respectively. Male faculty scored higher on opportunity exploration, formative investigation, championing, and application than their female counterparts. Innovative research behavior showed significantly positive associations with task-approach goals, negative associations with learning-approach goals, and no significant association with mastery-avoidance goals except the positive link of learning-avoidance goals to championing. These results have implications for understanding faculty research motivations and behaviors and effectively stimulating their innovativeness in research for sustainable development of higher education institutions.

1. Introduction

As a major source for organizational survival and sustainability [1], innovation could lead to changes in the organizations and the enhancement of competitiveness and professionalism [2]. This is especially true for innovation in research in higher educational institutions. Faculty members in higher education who are expected to publish a vast number of journal articles and conduct the most valuable research [3] are key resources for research [4]. Previous studies have demonstrated that their research innovation has been considered an essential factor closely related not only to their professional development [4,5] but also to the academic rankings of their institutions [6] and even to the national prosperity [7] and knowledge enhancement [8]. Such highlights emphasized the vital role of faculty members’ research innovation and the great need for higher education institutions to stimulate their members’ innovative behavior. However, it is also found that faculty members still face high levels of pressure and demanding research requirements set by their institutions [6], resulting in fewer and repetitive research outputs and several psychological issues, such as depression, emotional exhaustion, and low self-efficacy [9]. Thus, motivating their innovative behavior is of great significance [2] and has received great attention from policymakers, educators, and practitioners alike [10].

Innovative behavior is a multistage process involving the generation and implementation of new ideas or solutions and proved to be associated with several organizational and individual factors [11,12]. At the individual level, a recent review demonstrated that motivation was an important individual predictor of innovative behavior [13]. A highly motivated individual may exert great involvement in innovative behavior [14]. Thus, research motivation could predict research behaviors [6]. Of motivational theories, achievement goal theory has been used as a theoretical framework to interpret individuals’ driving for a particular activity in the achievement-related arena [15]. As research is a complex activity [9], involving multiple tasks evaluated differently for success, it constitutes an achievement-related motivational context for faculty members in which they learn new knowledge, compete with others, and strive for success [14]. As such, the research motivation of faculty members can be ideally explained under the guidance of achievement goal theory [14,16]. Achievement goal researchers also posit that different motivational mechanisms can be evoked by different achievement goals such as mastery goals and performance goals, resulting in different patterns of behavioral outcomes [17]. Accordingly, individual innovative behavior could be stimulated and regulated by different achievement goals [18].

Since the introduction of achievement goal theory into the study of teacher motivation, empirical studies have repeatedly reported its applications in various social–cultural settings [19]. In educational settings, exploration of the relationships between individual innovative behavior and achievement goals has been mainly undertaken in primary and secondary schools in Western societies, with a particular focus on teachers’ mastery goals (one class of achievement goals) and innovative behavior in teaching. There remain underexamined university faculty perceptions of mastery goals and their innovative behavior in both teaching and research [20]. Additionally, although individual innovative behavior has been theoretically considered a multistage process [11], it is often used as a unidimensional construct in empirical literature [21]. To increase the knowledge of faculty members’ innovative research behavior, there is a need to probe into the multiple stages of research behavior triggered by different research goals. Therefore, this study aims to explore characteristics of faculty-perceived mastery goals and innovative research behavior as well as the relationships between such goals and behaviors in mainland China, hoping to stimulate faculty members’ motivation and innovative behavior to the sustainable development of higher education institutions.

2. Literature

2.1. Mastery Goals

As one of the classic cognitive motivation theories, achievement goal theory reflects the purpose and reason for involvement in achievement-related activities [22] and provides a theoretical underpinning to explain achievement behaviors in different educational settings [23]. The classic distinction of achievement goals was made between mastery goals and performance goals. Mastery goals are directed at improving competence and mastering tasks, while performance goals are concerned with demonstrating competence relevant to others [24]. Based on the approach–avoidance distinction, Elliot and colleagues proposed a widely accepted 2 × 2 integrative model of four achievement goals [25,26]: mastery-approach goals, mastery-avoidance goals, performance-approach goals, and performance-avoidance goals [27,28].

Of different achievement goals, mastery goals view challenges and failure as a chance to learn, and thus, generally have positive associations with work-related behaviors [19,23]. Reviews of studies have indicated that a finer distinction between these goals may help to clarify and shed light on the different effects on experience and behaviors [14,17]. Therefore, in terms of task/intrapersonal standards, researchers have identified mastery-approach goals into task-approach goals (striving to do well on a task) and learning-approach goals (trying to develop and grow the competencies), and mastery-avoidance goals into task-avoidance goals (striving to avoid doing poorly on a task) and learning-avoidance goals (trying not to lose the competencies or missing the opportunities to grow them) [14,27], and made preliminarily explorations between these goals and different achievement-related outcomes [14,29].

Although individuals are assumed to pursue a single goal, the multiple goal perspective is becoming more popular with recent researchers [24]. The extensive application of achievement goals to the research of teacher motivations has been conducted at different educational levels [16,23,29]. In universities, empirical research has shown that achievement goals, especially mastery goals, had strong associations with university teaching practices, such as help-seeking behavior [30] and teaching approach [19]. As achievement goals for research are different from those for teaching, faculty members thus have partly different motivations in both domains [14]. However, in comparison with existing work on achievement goals for teaching, much remained unknown about achievement goals for research in universities, especially under the perspective of multiple goals. Although recent research found that professional learning gains [14] and engagement in questionable research practices [16] were closely linked with learning goals and task goals for researchers under the multiple goal perspective, empirical supporting evidence is still needed to examine the relationships between different mastery goals and different research-related behaviors, particularly in a non-Western context.

2.2. Innovative Behavior

Innovative behavior is described as all individual behaviors that aim to generate, promote, or implement beneficial development of new products, technologies, or processes at all organizational levels [31], and it is of significance for the organizations to increase their competitiveness and for individuals to enhance their well-being [32]. So far, researchers have proposed different theoretical frameworks to conceptualize and operationalize the innovative processes [31,32,33].

Of these different operationalizations, the most comprehensive and broadly accepted is the five-factor multidimensional measurement developed by Kleysen and Street, including opportunity exploration (e.g., looking for opportunities), generativity (e.g., producing beneficial changes), formative investigation (e.g., formulating, experimenting, and evaluating ideas and solutions), championing (e.g., persuading, pushing, supporting challenging and risky tasks), and application (e.g., implementing or modifying ideas or solutions). Although this measure often showed unstable results of factor analysis in many studies, it still demonstrated good reliability and multidimensional constructs [21,31]. Recently, Steyn and de Bruin (2019) clearly distinguished the five factors of individual innovative behavior with a sample of over 3000 employees and proved this five-factor measure with good psychometric features [21].

A review of empirical studies revealed that innovative behavior was influenced by a number of individual and organizational factors [34], of which individual factors were found to be particularly remarkable [32,35]. In educational settings, a majority of studies regarding innovative behavior were conducted with school teachers [13], and their motivational factors were found to be significant in stimulating their innovative behavior [36]. Recently, some researchers began to relate motivational factors to the innovative behavior of faculty members and found positive links between faculty innovative behaviors and their mastery goals [20].

2.3. Relationships between Mastery Goals and Innovative Research Behavior

Achievement goals are developed to interpret individual behaviors in achievement situations and provide a theoretical underpinning to investigate motivational factors and individual innovative behavior [37]. Of different achievement goals, mastery goals have been found positive for achievement-related behaviors [24]. Individuals pursuing mastery goals have a preference for challenging and risky tasks [37], and they are likely to perform innovative behavior as it involves risks, errors, or even a high likelihood of failure [38]. Previous studies suggested that mastery-oriented individuals tend to cope with obstacles or resistance by putting more effort into and persisting in their innovative jobs [39].

In both business and educational settings, empirical studies have revealed that the innovative behavior of employees, school teachers, and faculty members displayed positive links with their perceptions of mastery goals [20,35,36]. Compared with employees and school teachers, faculty innovative behavior has been less investigated [20]. As research constitutes achievement-related contexts [14], empirical studies have proved that faculty research motivation and its relations to research-related attitudes and behaviors could be well-explained under the theoretical underpinning of achievement goal theory [16]. However, typically nil findings were reported for the task-avoidance goals and learning-avoidance goals, and sometimes even negative results were reported for learning-approach goals [14,29]. Of the limited empirical studies, individual innovative behavior and mastery goals were assessed in unidimensional measures even if the two constructs were theoretically multidimensional [11].

Under the multiple goal perspective, there is a need to make a deeper exploration of different mastery goals for research of faculty members and how these different goals evoke the multiple stages of innovative research behavior to provide more supporting evidence for verifying the finer differentiation of mastery goals as well as exploring the relationships between different mastery goals and research-related behaviors. Therefore, based on the reviewed literature, this study aimed to explore the characteristics of and the relationships between faculty members’ mastery goals and their innovative behavior in the research context with a Chinese sample. Specifically, two research questions have been proposed: (1) What are the characteristics of faculty perceptions of their mastery goals for research and innovative research behavior? (2) What are the associations between faculty perceptions of their mastery goals for research and innovative research behavior?

3. Method

3.1. Participants

An online questionnaire survey was conducted based on an online platform Wenjuanxing. The participants were chosen by a convenient sampling approach. They were told the survey purpose and voluntarily and anonymously filled in the online questionnaire in January 2021 in Eastern China. A total of 621 out of 748 responses were valid, with an 83% valid response rate. Over three-quarters were female faculty members (n = 469, 75.5%). As for the teaching experience, approximately half of the participants (n = 305, 49.1%) had 10–20 years of teaching experience, 135 (21.7%) over 20 years, 93 (15%) 4–9 years, and 88 (14.2%) less than 3 years.

3.2. Instruments

There were two sections in this online questionnaire. Participants’ backgrounds were collected in the first section, covering gender and years of teaching experience. Two sets of measurements, mastery goals for research and innovative research behavior, were presented in the second section with 30 items in total.

3.2.1. Mastery Goals for Research

The 16-item measurement of mastery goals for research was adapted from Daumiller and Dresel’s (2020) faculty achievement goals for research. We translated all items into Chinese while slightly adapting the expressions of the items in the research context. The measurement items were preceded by a sentence stem saying, ‘In my current research activities…’. There were four subscales in mastery goals for research with four items each to measure: task-approach goals (for example, ‘…To accomplish the research requirements well is important to me’); task-avoidance goals (for example, ‘…my main concern is to avoid not fulfilling research assignments poorly’); learning-approach goals (for example, ‘…my main task is to further enhance my research competences’); and learning-avoidance goals (for example, ‘…my main task is to avoid not developing my research competences’). As the original scale of faculty achievement goals for research was assessed by an 8-point Likert scale, we adopted such an 8-point scale to assess mastery goals to maintain originality. The Likert scale ranged from 1 ‘completely disagree’ to 8 ‘completely agree’.

3.2.2. Innovative Research Behavior

The 14-item measurement for innovative research behavior was adapted from the five-factor measurement developed by Kleysen and Street in 2001, namely, opportunity exploration, generativity, formative investigation, championing, and application, and we slightly adapted it in the research context with a sentence stem of: ‘In your current research work, how often do you…’. Three items were included in opportunity exploration, e.g., ‘Look for research opportunities’; two items were in generativity, e.g., ‘Generate research ideas’; three items were in the formative investigation, e.g., ‘Test out research ideas’; three items were in the championing, e.g., ‘seeking support for research ideas’; three items were in the application, e.g., ‘Implement research activities’. Following the original 6-point Likert scale of innovative behavior, each item was scored from 1 ‘never’ to 6 ‘very often’.

3.3. Data Analysis

We used Mplus 8.3 to perform the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation model (SEM) with the maximum likelihood (ML) estimator and SPSS 23.0 to address reliability, descriptive statistics, cross-correlations, and the multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). CFA was used to assess the factorial structure. Differences in levels of mastery goals and innovative behavior across the demographic variables were then tested using MANOVA. SEM was constructed last to explore the relationships between mastery goals and innovative research behavior. Model fit was assessed with root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (<0.08), comparative fit index (CFI) (>0.90), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) (>0.90) [40] as well as Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC) (the smaller, the better) [41]. The effect sizes of correlations were interpreted with the following guidelines: small, 0.10 to <0.20; medium, 0.20 to <0.30; large, ≥0.30 [42].

4. Results

4.1. Construct Validity and Reliability

The measurement models are summarized in Table 1. We compared four measurement models of mastery goals for research (a one-factor model, an approach-avoidance model, a task-learning model, and a four-factor model) and two models of innovative research behavior (a one-factor model and a five-factor model) based on the literature reviewed. After comparing different model data, we found that the four-factor model of mastery goals (χ2 = 436.44, df = 98, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.075, TLI = 0.92, CFI = 0.93) was better than the other models, and the five-factor model of innovative research behavior (χ2 = 216.80, df = 67, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.060, TLI = 0.97, CFI = 0.98) was better than the one-factor model. Accordingly, we selected the four-factor mastery goals for research and the five-factor innovative research behavior for further analyses.

Table 1.

Measurement models of mastery goals for research and innovative research behavior.

As can be seen from Table 2, Cronbach alpha coefficients of all measures ranged from 0.86 to 0.96, displaying good internal consistency. The standardized factor loadings were between 0.76 to 0.97, all statistically significant (p < 0.001). The average variance extracted of the measurement was over 0.50, and the composite reliability of the measurement was over 0.70, suggesting a good convergent validity of each subscale [43]. Additionally, the correlations of each factor were lower than the value of the square root of average variance extracted [43], indicating a good discriminate validity.

Table 2.

Construct validity, factor loadings, internal consistency, correlations, and descriptive statistics (N = 621).

4.2. Descriptive Analysis and Cross-Correlations

The means and their standard deviations of mastery goals for research and innovative research behavior are shown in Table 2. We used the midpoint of the Likert scales as the referent and mean scores that were more than the midpoint were considered as high. Accordingly, the mean scores of four mastery goals were much higher on an 8-point Likert scale (4.5 as the midpoint). The mean scores of five innovative behavior factors were around its average score of 3.5 (on a Likert scale of 6-point). Specifically, the faculty-perceived mean score for learning-approach goals (M = 7.28, SD = 1.10) was the highest among the four mastery goals, and that of task-avoidance goals (M = 6.59, SD = 1.47) was the lowest. The mean score of championing (M = 3.39, SD = 1.21) was below the average of 3.5, ranking the lowest among the five innovative behaviors. As for the correlation matrix, the four mastery goals for research and the five innovative research behaviors were significantly and positively correlated with each other, with effect sizes ranging from 0.11 to 0.90.

4.3. Comparison of Differences

The differences in the demographic variables were analyzed through the conduct of MANOVA. Results showed that differences across each group were significant statistically with a p-value less than 0.001. However, the global effect size of years of teaching experience (partial η2 = 0.02) was very small and had no statistical significance. Gender exhibited a significant statistically effect (F (9, 553) = 2.26, p < 0.05, Wilk’s λ = 0.97) with a small effect size 0.04.

Tests of between-subjects effects showed that male and female faculty differed significantly only in innovative research behavior but not their mastery goals. Through estimated marginal means, Table 3 indicates that mean scores of male faculty were significantly higher than those of female faculty in opportunity exploration, formative investigation, championing, and application.

Table 3.

Gender differences in innovative research behavior (N = 621).

4.4. SEM

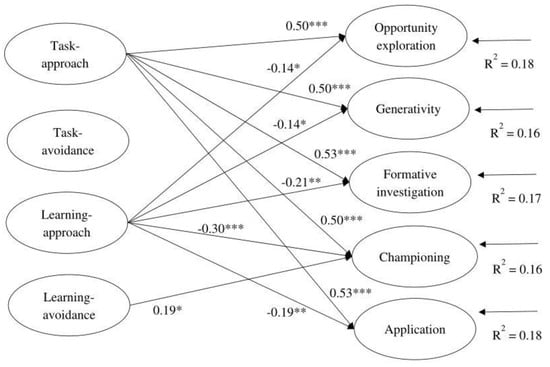

Our last set of analyses examined the associations between faculty-perceived mastery goals for research and their innovative research behavior. We used SEM to construct a model, which assumed that mastery goals for research (independent variables) and innovative research behavior (dependent variables) were closely linked. Figure 1 of the SEM results reveals that the structural model of the relationships between mastery goals for research and their innovative research behavior showed acceptable model fit indices (χ2 = 1564.93, df = 369, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.072, TLI = 0.94, CFI = 0.95), explaining substantial amounts of variance of innovative research behavior from 0.16 to 0.18. Generally, task-approach goals were more powerful in explaining different aspects of innovative behavior and were significantly and positively associated with each innovative research behavior (p < 0.001, β ≥ 0.50). Learning-approach goals were significantly and negatively associated with championing (p < 0.001, β = −0.30), formative investigation (p < 0.01, β = −0.21), application (p < 0.01, β = −0.19), opportunity exploration (p < 0.05, β = −0.14), and generativity (p < 0.05, β = −0.14). Mastery-avoidance goals (including task-avoidance goals and learning-avoidance goals) displayed no significant association with innovative research behavior except the positive link of learning-avoidance goals to championing (p < 0.05, β = 0.19).

Figure 1.

Significant regression path of SEM (N = 621), Note: Goodness-of-fit indices: χ2 = 1564.93, df = 369, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.072, TLI = 0.94, CFI = 0.95; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

5. Discussion

Our study contributes to the literature on the sustainable development of faculty members’ motivation and innovative behavior in the research context by revealing the characteristics of mastery goals and innovative behavior and verifying their relationships. Results from the survey data validated the adapted scales assessing the multidimensional structures of mastery goals and innovative research behaviors with a sample of Chinese faculty. Meanwhile, the results revealed the unique characteristics of faculty-perceived mastery goals and innovative behaviors and clarified the multiple relationships between them in the research context. These results offer new insight into the understanding of sustainable development of faculty members’ psychological state and behavior in the research context.

5.1. Characteristics of Mastery Goals for Research and Innovative Research Behavior

Concerning the validation of the adapted scales, four-factor mastery goals, consisting of task-approach goals, learning-approach goals, task-avoidance goals, and learning-avoidance goals, provide an applicable framework for conceptualizing faculty-perceived mastery goals for research, which is consistent with Daumiller and Dresel’s (2020) study with German faculty. As for innovative behavior, although it was well acknowledged as a multistage construct, the majority of previous studies failed to support the original five-factor structure [31,44]. Steyn and de Bruin (2019) provided preliminary evidence for the five-factor structure with a sample of over 3000 employees from different occupations in South Africa. The results of our study further added empirical support for the multistage construct of innovative behavior and validated the scale of faculty innovative research behavior in the Chinese context.

Descriptive results revealed some characteristics of Chinese faculty-perceived mastery goals for research. The mean scores of four mastery goals were significantly higher than the midpoint (4.5), which suggested that Chinese faculty perceived their competence improvement and task fulfillment as the main sources of their research achievement. This result was consistent with Daumiller and Dresel’s (2020) findings on German faculty. Additionally, Chinese faculty scored the highest on learning-approach goals (M = 7.28, SD = 1.10), which suggests that they focus more on improving their research-related competence. However, German faculty reported higher mean scores for both task-approach goals (M = 7.24, SD = 0.80) and learning-approach goals (M = 7.25, SD = 0.86) than that of other goals, indicating that they perceived competence development and tasks as equally important; that is, both the improvement of their research ability and the better completion of research-related tasks are significant for them. This slight difference between our study and that of Daumiller and Dresel might be related to the participants of the two studies. Our participants were full-time faculty members whereas their study involved both faculty members and doctoral students. In Germany, unlike educational systems in other countries, doctoral students need to fulfill their research requirements and take up positions of teaching undergraduate courses [29]; thus, they are often considered researchers and academic staff [14], and their assignments and responsibilities make them more learning-oriented and task-oriented.

This study also revealed some characteristics of innovative research behavior. First, faculty reported moderate levels of innovative research behavior in general, indicating that they occasionally participated in innovative research-related activities. This finding might be related to the overwhelming number of research tasks Chinese faculty undertake and the assessment requirements they have to fulfill. Studies have indicated that when confronted with those tasks and requirements, they may not want to follow the significant but time-consuming research issues, but adopt available practices, paradigms, and approaches [45,46]. Thus, what they generate may be low-quality or old-fashioned research outcomes or discoveries [45,46]. Our results also showed the mean score of championing was the lowest of the five factors of innovative behaviors, indicating that the frequency of faculty seeking support for challenging and risky research tasks was lower than that of other research activities. This is possibly due to the faculty’s willingness to keep friendly social relations in the research context [4]. Since a social process occurred during the innovation development [47], pushing forward and supporting a new idea for change may meet resistance from people who want to avoid the insecurity of changes and keep preferences for well-established paradigms [39]. The resistance could be perceived as interpersonal conflict [48]. Consequently, to avoid conflict and maintain a harmonious social relationship with people around them, faculty may be less likely to push new ideas into implementation or get support for challenging and risky research tasks.

Furthermore, MANOVA revealed some significant differences between different genders among faculty members. We found that the means scores of male faculty in the four factors of innovative research behavior, namely, formative investigation, application, opportunity exploration, and championing, were higher than those of female counterparts, indicating that female faculty may be less proactive in exploring, investigating, promoting, and implementing new ideas than male counterparts. The results might be related to the specific context faced by faculty members. In higher education institutions, much more pressure was undertaken on female faculty members due to the demanding research requirements and greater teaching workload, as well as the higher social expectations of family responsibilities and parenting [46]. Therefore, they would feel insecurity, uncertainty, and anxiety, and not have enough time to produce high-quality research output or novel discoveries, but stick to mainstream research topics and methods [45], leading to low participation in innovative research-related activities.

5.2. Relationships between Mastery Goals for Research and Innovative Research Behavior

Consistent with the literature, our SEM results revealed positive relationships between task-approach goals and all five factors of innovative research behavior with strong effect sizes, indicating that faculty striving to fulfill the requirements of research tasks were more likely to carry out innovative research-related activities. According to achievement goal theory, individuals who consider task-based goals as their pursuit may deem the task as the evaluative reference for competence and require minimal cognitive processing to discern the extent to which one has completed a task [15]. Thus, individuals could receive immediate and ongoing feedback directly during task involvement and keep engaged in the task [15]. In addition, a full commitment to and immersion in the task may be promoted by individuals who pursue approach-based goals, and accordingly, individuals striving for task-approach goals are more likely to facilitate engagement in the task [24]. For faculty whose primary task is to conduct research [49], those pursuing task-approach goals are constantly engaged in research-related tasks, such as making new knowledge public, developing new research designs, producing high-quality publications, or applying for research funding and projects [50]. Accordingly, it might be possible for faculty who focus on better completion of research tasks to get involved in innovative activities in their research to improve their research productivity and fulfill research requirements.

Contrary to expectations, our results showed that learning-approach goals had negative associations with all the five factors of innovative research behavior, even though faculty scored learning-approach goals the highest of the four mastery goals. Theoretically speaking, learning-approach goals were more positive to achievement-related outcomes, such as achievement behaviors and attitudes; in practice, the relationships between learning-approach goals and achievement-related outcomes are often controversial because learning-approach goals are context-based and less process-oriented [15,29]. Upon closer examination, Daumiller and Dresel’s (2020) study with German faculty reported positive relationships between professional learning in the domain of research and learning-approach goals for research whereas Janke and his colleagues (2019) revealed that learning-approach goals of university researchers were negatively related to questionable research practices. The results of this study found that faculty who wanted to develop their research competence were unwilling to get involved in innovative research-related activities and provided empirical evidence to support the fact that the research behaviors of Chinese faculty members negatively correlated to their learning-approach goals. This discrepancy probably was because of the nature of learning-approach goals. Based on the intrapersonal standard, learning-approach goals were more separable from task engagement in that individuals would compare their current competence to a mental representation at another point in time [24]. Therefore, although Chinese faculty perceived learning-approach goals as an important aspect of motivation for research, they would still prefer to focus on developing and growing their own research competence rather than take risks to innovate in research.

We also revealed that mastery-avoidance goals had no significant association with the five factors of innovative research behavior, except that learning-avoidance goals were positively linked with championing. Similarly, existing studies have also indicated no significant relationships between research-related outcomes and mastery-avoidance goals, such as professional learning, research affections, and fraudulent research behavior [14,16]. The insignificant relationship may result from the valence of avoidance goals. Focused on failure, avoidance-based goals tend to prevent full investment in the tasks because of the perceived anxiety and threat caused by the possibility of failure [15,51]. Thus, mastery-avoidance goal pursuit, including task-avoidance and learning-avoidance goals, may move away from innovative behavior which involves uncertainty and failure. Furthermore, the positive link of learning-avoidance goals to championing indicated that faculty who feared that they might not develop their research competence were more likely to seek support for their research tasks. This was probably because the improvement of faculty research competence needs more external support from social networks, such as more mentoring and closer connections to colleagues [4,52]. Future research may further investigate possible relationships between mastery-avoidance goals and achievement-related outcomes to provide more empirical evidence.

6. Limitations

This study explored the characteristics of the faculty-perceived mastery goals for research and their innovative research behavior and their relationships in mainland China. Several limitations remain for future considerations. First, this study was a cross-sectional and exploratory design, which makes it insufficient to verify the causal relationships between the two variables explored in this study. Therefore, a longitudinal design is expected in future research to document faculty-perceived mastery goals and provide a closer examination of the directions of relationships. Second, as a preliminary study, one of our research aims is to explore the general characteristics of Chinese faculty members’ mastery goals for research and their innovative research behavior. We did not further explore the differences in faculty perceptions that might be caused by institutional factors. Future research may use multilevel analysis to deal with the nested data. Third, this study used a self-rated questionnaire for all variables which cannot inevitably rule out subjective experiences and source bias. Accordingly, relevant measures are needed to be taken to address such bias for future research.

7. Conclusions and Practical Implications

Our study adapted achievement goal orientation theory as a theoretical framework to study faculty research motivation and their research behavior through investigating and revealing some characteristics of and the relationships between different mastery goals and multiple stages of innovative research behavior. Results from an anonymous questionnaire survey of 621 Chinese faculty members revealed a high level of mastery goals for research and a moderate level of innovative research behavior. Male faculty scored higher on opportunity exploration, formative investigation, championing, and application than their female counterparts. Innovative research behavior showed significantly positive associations with task-approach goals, negative associations with learning-approach goals, and no significant association with mastery-avoidance goals except the positive link of learning-avoidance goals to championing. Our results provide significant implications for the understanding of faculty research motivations and the promotion of their innovative behavior for their sustainable development in the research context.

First, the complex relationships between mastery goals and innovative behavior underscore the significance to understand the two constructs comprehensively. Administrators or policymakers may consider the multidimensionality of mastery goals for research and finely differentiate mastery goals based on task standards and intrapersonal standards when they formulate research-related policies and design sustainable professional development programs aimed at stimulating faculty research motivation. For example, they may consider setting definite task-oriented research assignments in terms of task goals and stimulating faculty members’ professional learning and improving their research competence through clear research objectives. Concerning innovative behavior, practical strategies to promote faculty innovation for research might be devised and implemented in correspondence to specific stages, such as seeking research opportunities, generating research ideas, looking for research support, and so on, rather than from an overall perspective.

Second, the positive relationships between task-approach goals and innovative research behavior indicate the need for faculty members to be encouraged to innovate in research through sustainable task-oriented research assignments. The positive link of learning-avoidance goals to championing indicated that providing adequate social support would help to stimulate faculty members to innovate in research-related activities. Faculty may also be encouraged to share ideas and collaborate in research groups to make full use of the social support from administrators and colleagues alike. Additionally, the negative relationships between learning-approach goals and innovative behavior indicated that faculty may be encouraged to conduct research activities directed at personal learning and provided with sufficient research support in sustainable research environments, such as training and autonomy, to alleviate their anxiety, uncertainty, and insecurity when faced with research challenges and risks.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Visualization, C.G. Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the High-level Cultivation Project of Shandong Women’s University under Grant No. 2021GSPSJ09.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Participants Ethics Committee of Shandong University, China.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lee, W.R.; Choi, S.B.; Kang, S.-W. How leaders’ positive feedback influences employees’ innovative behavior: The mediating role of voice behavior and job autonomy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Qing, C.; Jin, S. Ethical leadership and innovative behavior: Mediating role of voice behavior and moderated mediation role of psychological safety. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-F.; Shin, J.-C. The research–teaching nexus among academics from 15 institutions in Beijing, Mainland China. High. Educ. 2015, 70, 375–394. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Factors that Motivate Academic Staff to Conduct Research and Influence Research Productivity in Chinese Project 211 Universities; University of Canberra: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, M.; Li, L. Early career researchers’ perceptions of collaborative research in the context of academic capitalism on the Chinese Mainland. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 1474–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupnisky, R.H.; Hall, N.C.; Pekrun, R. Faculty enjoyment, anxiety, and boredom for teaching and research: Instrument development and testing predictors of success. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 1712–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, H.M.G.; Richardson, P.W. Motivation of higher education faculty: (How) it matters! Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 100, 101533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. Teacher–researcher role conflict and burnout among Chinese university teachers: A job demand-resources model perspective. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 44, 903–919. [Google Scholar]

- Aprile, K.T.; Ellem, P.; Lole, L. Publish, perish, or pursue? Early career academics’ perspectives on demands for research productivity in regional universities. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 40, 1131–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daumiller, M.; Stupnisky, R.; Janke, S. Motivation of higher education faculty: Theoretical approaches, empirical evidence, and future directions. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 99, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 580–607. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K.B.; Ullah, S.M.E.; Choi, S.B. The mediated moderating role of organizational learning culture in the relationships among authentic leadership, leader-member exchange, and employees’ innovative behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurlings, M.; Evers, A.T.; Vermeulen, M. Toward a model of explaining teachers’ innovative behavior. Rev. Educ. Res. 2015, 85, 430–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daumiller, M.; Dresel, M. Researchers’ achievement goals: Prevalence, structure, and associations with job burnout/engagement and professional learning. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elliot, A.J.; Murayama, K.; Pekrun, R. A 3 × 2 achievement goal model. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 103, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janke, S.; Daumiller, M.; Rudert, S.C. Dark pathways to achievement in Science: Researchers’ achievement goals predict engagement in questionable research practices. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2018, 10, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulleman, C.S.; Schrager, S.M.; Bodmann, S.M.; Harackiewicz, J.M. A meta-analytic review of achievement goal measures: Different labels for the same constructs or different constructs with similar labels? Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 422–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runhaar, P.; Sanders, K.; Yang, H. Stimulating teachers’ reflection and feedback asking: An interplay of self-efficacy, learning goal orientation, and transformational leadership. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 1154–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yin, H.; Wang, W. Exploring the relationship between goal orientations for teaching of tertiary teachers and their teaching approaches in China. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2015, 16, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yean, T.F.; Johari, J.; Yahya, K.K. Contextualizing work engagement and innovative work behaviour: The mediating role of learning goal orientation. Eur. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, R.; de Bruin, G. The structural validity of the innovative work behaviour questionnaire: Comparing competing factorial models. South. Afr. J. Entrep. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.R. An Achievement goal theory perspective on issues in motivation terminology, theory, and research. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butler, R. Teachers’ achievement goal orientations and associations with teachers’ help seeking: Examination of a novel approach to teacher motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Dweck, C.S.; Yeager, D.S. Handbook of Competence and Motivation: Theory and Application; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot, A.J.; Church, M.A. Hierarchical model of approach and avoidance, achievement motivation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 72, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Harackiewicz, J.M. Approach and avoidance achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: A mediational analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; McGregor, H.A. A 2 × 2 achievement goal framework. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.B.; Moon, K.S.; Park, S. When is a performance-approach goal unhelpful? Performance goal structure, task difficulty as moderators. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2021, 22, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, J.; Janke, S.; Daumiller, M.; Dresel, M.; Dickhäuser, O. No learning without autonomy? Moderators of the association between university instructors’ learning goals and learning time in the teaching-related learning process. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2020, 83, 101937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daumiller, M.; Dickhauser, O.; Dresel, M. University instructors’ achievement goals for teaching. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kleysen, R.F.; Street, C.T. Toward a multi-dimensional measure of individual innovative behavior. J. Intellect. Cap. 2001, 2, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukes, M.; Stephan, U. Measuring employee innovation: A review of existing scales and the development of the innovative behavior and innovation support inventories across cultures. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, J.; Den Hartog, D. Measuring innovative work behaviour. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2010, 19, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cui, T.; Cai, S.; Ren, S. How and when high-involvement work practices influence employee innovative behavior. Int. J. Manpow. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.; Kim, T. An integrative literature review of employee engagement and innovative behavior: Revisiting the JD-R model. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runhaar, P.; Bednall, T.; Sanders, K.; Yang, H. Promoting VET teachers’ innovative behaviour: Exploring the roles of task interdependence, learning goal orientation and occupational self-efficacy. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2016, 68, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janssen, O.; Yperen, N.W.V. Employees’ goal orientations, the quality of leader-member exchange, and the outcomes of job performance and job satisfaction. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 368–384. [Google Scholar]

- Hirst, G.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Zhou, J. A cross-level perspective on employee creativity: Goal orientation, team learning behavior, and individual creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.A.; Buckley, F. Work engagement antecedents, the mediating role of learning goal orientation and job performance. Career Dev. Int. 2011, 16, 684–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- van de Schoot, R.; Lugtig, P.; Hox, J. A checklist for testing measurement invariance. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 9, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, G.E.; Szodorai, E.T. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 102, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, A.W.; Turek, D. Innovativeness in organizations: The role of LMX and organizational justice. The case of Poland. Synerg. Int. J. Synerg. Res. 2013, 2, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, M.; Lu, G. What price the building of world-class universities? Academic pressure faced by young lecturers at a research-centered university in China. Teach. High. Educ. 2017, 22, 957–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Su, Y.; Ru, X. Perish or publish in China: Pressures on young Chinese scholars to publish in internationally indexed journals. Publications 2016, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Messmann, G.; Mulder, R.H. Innovative work behaviour in vocational colleges: Understanding how and why innovations are developed. Vocat. Learn. 2010, 4, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Innovative behaviour and job involvement at the price of conflict and less satisfactory relations with co-workers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2003, 76, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.A. Research vs. non-research universities: Knowledge sharing and research engagement among academicians. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, G. The human dimensions of the research agenda: Supporting the development of researchers throughout the career life cycle. High. Educ. Q. 2005, 59, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yin, H. Teacher motivation: Definition, research development and implications for teachers. Cogent Educ. 2016, 3, 1217819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yin, H.; Wang, W. The effect of tertiary teachers’ goal orientations for teaching on their commitment: The mediating role of teacher engagement. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 36, 526–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).