1. Introduction

In the past few years there has been an increasing amount of research focusing on ‘generation rent’, referring to a high share of young people for whom the rental sector is the only realistic tenure choice for independent living in the long term. Existing research on ‘generation rent’ focuses mainly on Anglo-Saxon, and to some extent, Western European, Mediterranean [

1,

2,

3], and Asian countries [

4,

5,

6]. Analysis that focuses on Central and Eastern Europe is scarce. Some research exists on certain aspects of young people’s housing careers covering Central and Eastern Europe, such as the time of home leaving, the use of mortgage loans in home acquisition [

7,

8,

9], or semi-independent living [

10,

11], but this literature does not focus on the specific role of rental housing in young people’s housing careers.

The emergence of ‘generation rent’ can be discussed in the framework of general social and economic changes, such as the increased flexibility and decreased stability of the labor market [

6,

10], as well as changing welfare models [

12]. It can also be put in a youth sociology perspective, emphasizing the role of housing in the transition between youth and adulthood [

2,

6,

10] and the increasingly non-predictable and non-linear nature of such a transition [

10,

13], which makes settling down problematic [

13], as well as highlighting young people’s specific situation in the housing market due to their economic vulnerability and inexperience, among other issues [

12,

14]. The appearance of such a ‘generation rent’ can also be discussed in a housing sociology framework. Here, housing market trends are emphasized, such as increased property prices, the decreased availability of mortgage loans, and the shrinking of the social rental sector in many countries [

12,

15], with the parallel increase in the private rental sector [

16] and the emergence of new housing forms, such as new types of co-housing [

6,

17,

18]. However, some literature also points out that young people’s housing careers are set within specific housing systems and welfare regimes [

10,

11]. In addition, housing opportunities and their limitations are influenced by housing policies: states have a predominant role in influencing the attractiveness of specific tenures through housing policy measures [

7,

19] and shaping the regulatory framework and subsidies [

20]. In addition, the discursive framework of the housing policy has an effect on people’s perceptions of housing tenures and tenure choices [

21]. The above suggests that the emergence and specificities of a ‘generation rent’ may differ in different contexts.

The present analysis provides some insights into the applicability of the concept of ‘generation rent’ in one of the ‘super-homeownership’ housing regimes, with strong context dependencies. First, we define the concept of ‘generation rent’ and its main attributes. Then, we briefly present the current Hungarian housing and welfare regime that severely limits the opportunities for lower status young adults to find suitable housing. In the following, we analyze young people’s housing according to three aspects: trends in young people’s housing tenure, based on data from the Central Statistical Office and on our survey data of 2017; young people’s attitudes towards different tenure forms, presenting differences between young people with different housing experiences; and their housing career plans. The article also discusses the applicability of the concept of ‘generation rent’ and its specificities in relation to the Hungarian context.

The paper’s focus is on the period before the COVID-19 outbreak. In the meantime, several changes have occurred influencing housing choice and opportunities, including the collapse of overtourism and the connected short-term touristic rental market, leading to increased supply in the private rental market, and, albeit temporarily, decreasing property price and private rent level, as well as decreasing job opportunities in the tourism and hospitality industry, which affected young people’s income generation opportunities. However, an examination of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on housing choices is out of scope of the present study; we concentrate on the situation before 2019, and will cover the changes caused by the pandemic in future publications.

2. Materials and Methods

The findings are based on Housing Survey data of the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, and a survey conducted by the authors in 2017. The sample is comprised of 800 households residing in Budapest. Households were selected with random household sampling, and respondents were household members in the 18–35 age group.

Since different housing paths are actually implemented in certain, localized housing and labor markets [

22], a specific location was selected for our study. As the center of economic activities, as well as tertiary education in the country, combined with tourism, Budapest experiences the highest pressure on the housing market, resulting in the highest property and rental prices in the country, but also the widest supply of available properties.

The main issues covered by the questionnaire included past and present housing experiences, circumstances of leaving the parental home, perceptions and attitudes regarding different housing tenures, and housing career prospects and plans.

Our research hypothesis was that even though the role of the private rental sector is increasing in the housing trajectories of young people, acquiring housing property is still of great importance among young people, reflecting Hungary’s strongly ownership-oriented housing regime and public discourse, while the chances of acquiring such property are limited, and socially disparate. Moreover, we hypothesized that the acceptance of rental housing as a longer-term housing solution is discernible among young people. Thereby the term ‘generation rent’ is applicable in the Hungarian context; however, the development of a Hungarian ‘generation rent’, their housing experiences, and housing career plans, is strongly contingent upon the Hungarian housing regime context.

Generation Rent: Definitional Issues

The term ’generation rent’ appeared in the international housing literature relatively recently, in the 2010s [

23], and as it touched upon a recent social trend with a strong socio-economic impact, it soon received significant media attention, especially in the UK. In October 2011, only a few months after the publication of the first comprehensive report on young people’s difficulties in purchasing property [

23], ‘generation rent’ was listed as a buzzword by Macmillan Dictionary [

24]. Perhaps due to its relative novelty and its popularity outside scientific discourse, the way the phrase is used is still somewhat ambiguous.

The literature is consistent in that ‘generation rent’ refers to the phenomenon of young people living in the rental sector in a high proportion. However, it is not clear how high such a share should be in order to label a cohort as ‘generation rent’, and what should be the basis of comparison: earlier generations’ tenure structure, current older generations’ tenure, [

25], or alterations from the total populations’ tenure structure?

There is also a question concerning whether ‘generation rent’ should be explored as a static or dynamic phenomenon. Some studies focus on young people’s actual housing tenure (e.g., [

26]), whereas others apply a dynamic perspective and explore young people’s specific housing trajectories (e.g., [

23,

27,

28]). The latter recognize ‘generation rent’ as a currently young generation which might proceed to further phases in life without accessing homeownership, thereby potentially experiencing situations in life which earlier were thought to be experienced in an owner occupied home, such as child raising (see, e.g., [

29]).

The definition of young people may also differ somewhat, ranging from mid-teenagers (see, e.g., [

28]), or using the legal age of adulthood as a lower end of the scale (18 years as used in [

17]) up to 30 years [

12] or the mid-30s [

30]. Some scholars emphasize the heterogeneity of such a young group in terms of age, differentiating between younger and older cohorts [

27,

28,

30].

In the present article, we will explore the housing tenure of young people aged 18–35, compared both to earlier young generations’ tenure and to older generations’ tenure in order to outline the differences.

3. Results

3.1. The Hungarian Context: Housing Regime

3.1.1. Super-Homeownership Tenure Structure with an Emerging, yet Insecure, Private Rental Sector

The Hungarian housing system is characterized by a ’super-homeownership’ tenure structure [

31]; 86% of the population lives in owner-occupied housing, and 14% in public housing (mainly owned by local governments), or in private rental housing [

32,

33]. The relatively small private rental sector presents affordability and security problems due to the state’s laissez-faire approach towards regulating the sector, the lack of an effective system of dispute resolution and law enforcement [

34,

35,

36,

37], and not unrelated to the above, the high prevalence of informality. Nevertheless, the size of the sector and its significance in housing trajectories is on the rise. Between 2003 and 2015, the proportion of the private rental sector (PRS) increased from 2.5% to 6% [

35,

36], and while between 1996 and 2003, 11% of households that were mobile in the housing market moved to private rental housing, this proportion tripled to 28% between 2005 and 2015. Among those planning to change dwellings, such an increase was even more predominant: the proportion of those planning to move to PRS increased from 2% to 13% [

36]. Many choose PRS because they have no chance (no assets, state subsidy, or intergenerational transfer) to enter the housing market [

38]. Meanwhile, the profile of the sector is changing. In addition to a more traditional overrepresentation of higher income households, lower income households are increasingly overrepresented in the PRS [

39].

3.1.2. Homeownership-Oriented, Better-Off Focused Policy Framework

Housing policies tend to favor homeownership over renting since Hungary changed from socialism to a market economy in 1989/1990. First, a ‘right to buy’ scheme for sitting tenants was introduced, followed by the development of a subsidized housing finance system from the early 2000s [

40]. The dominance of state-subsidized mortgages ended with the proliferation of foreign currency loans in 2004. The mortgage loan to GDP ratio increased dramatically, by 22%, over ten years (2000—2%; 2009—24%). Hungary was hit hard by the great financial crisis (GFC) in 2008 due its large share of foreign currency loans [

41]. After the crisis, stricter lending rules were introduced (e.g., the withdrawal of foreign currency loans, and maximization of the percentage of income that can be spent on loan repayment) [

8]. However, no reconsideration of government policies in terms of tenure-orientation took place as a reaction to the GFC [

32].

Since the mid-2010s, the ownership orientation of government policies became even more prominent, with major subsidy schemes linked to the government’s flagship political agenda to increase fertility rates. In 2016 the so-called ‘Family Home Creation Allowance’—an already existing subsidy scheme supporting the home acquisition of households with existing, or committed children—was significantly extended, with especially high subsidies (non-refundable subsidies and state subsidized mortgages) available for newly constructed housing for households with three children (existing, or committed). The scheme was further developed in the following years, especially in terms of the widening availability of the subsidized mortgage scheme, but its logic persisted—available subsidies are dependent on the number of children, and the type of housing, with the purchase of new housing eligible for more subsidy. Since the mid-2010s, promoting the acquisition of newly constructed housing is supported by further policy measures, such as a decrease in value added tax (VAT), in the case of newly constructed housing properties, a VAT refund for self-initiated housing construction, and the simplification of the construction permit administration [

42]. Since 2019, the ownership-orientation of policies further increased with the introduction of a non-refundable subsidy for households with children (existing or committed) to buy and renovate property in depopulating rural areas (the so-called ‘Rural Family Home Creation Allowance’), and state-supported home equity loans (entitled ‘Baby Expecting Loan’) which became available for young people committed to having children; however, due to their timing, our survey could not reflect upon such developments.

As discussed above, major housing subsidy schemes are unavailable to households with no children, and/or not willing to contractually commit themselves to have children in the coming years.

In addition, such schemes are systematically less accessible, or are only accessible on a lower subsidy level, for lower status households with no savings and/or access to other forms of financial assets (e.g., intergenerational transfers), and a low and/or unstable income. In case of the Family Home Creation Allowance, some eligibility criteria systematically exclude certain low-status households (e.g., eligible applicants should possess a certain period of social security coverage, public work program employees are excluded from the scheme offering the highest amount of non-refundable subsidies); non-refundable subsidies require additional housing finance sources to acquire homeownership, which low-status households are less likely to have access to; those purchasing used flats—more realistic for households with fewer financial resources—are only eligible for lower subsidies; and in the case of state-subsidized loans, creditworthiness must be proved (and maximization of the monthly repayment/income ratio, discussed above, is applied). It should be noted that access to the non-refundable subsidy, introduced in 2019, for young households to buy and renovate property in depopulating rural areas is likely to differ somewhat from the above; however, this is not analyzed in the present study.

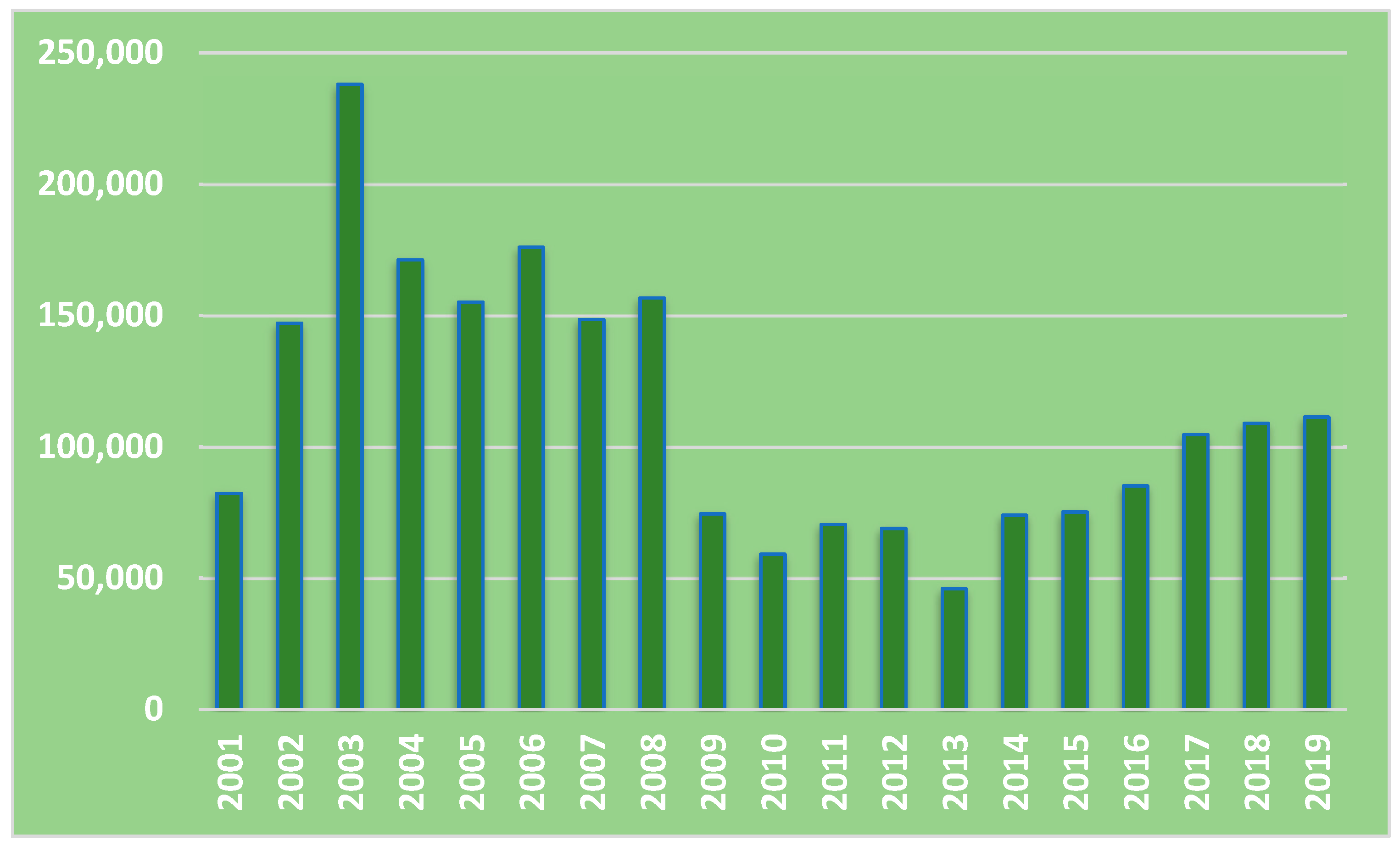

As a result of the developments in recent years, mortgages have picked up again [

8] (

Figure 1). In addition, the bias towards higher status households in housing-related central budget expenditures further increased. In 2015, before the introduction of a new set of measures to promote homeownership, 66% of central budget expenditures were non-socially targeted, which increased to over 90% in 2018 [

42].

In addition to the strong ownership orientation of policy measures, public policy discourse also strongly favors homeownership, and links the concept of ‘home’ with owner-occupied housing.

3.1.3. Property Market

The effect of housing policies on the Hungarian housing market is strong alongside market trends [

32,

43,

44,

45]. Improvements in the overall state of the economy, together with housing policy measures promoting homeownership, contributed to a sharp increase in housing market dynamics and property prices from 2014 on, subsequent to the decrease/stagnation following the GFC of 2008 [

8]. The number of housing transactions started to increase again in 2013, doubling by 2019. Housing prices started to rise from 2014 onward, up to 170%, according the nominal property price index, relative to 2015 (

Figure 2). In Budapest, the price of an average used dwelling more than doubled between 2015 and 2019, while the price of new dwellings increased by 72% [

44] (

Figure 3). According to real estate experts, in 2019, an average priced 50-square-meter apartment in Budapest costed 8.3 years of average income [

46].

3.1.4. Affordability Problems in the PRS

Along with a general increase in property prices, the spreading of short-term letting for tourist purposes, mainly through Airbnb, led to a rental price boom in the past few years (which was stopped by the outbreak of COVID-19 in early 2020, and began to increase again in 2022) (

Figure 4). Between 2011 and 2016, rental market prices increased by an average of 87% in Hungary. In the capital of Budapest, the rent for a specific private rental flat increased by 11–13% each year from 2016 on [

37,

47].

Private rentals became, by far, the least affordable sector of the housing market [

48,

49]. While the proportion of households with serious housing cost overburden—total housing costs (net of housing allowances) more than 40% of the total disposable household income—varied between 10 and 13% in the last years in the total population, the share was definitely higher among tenants paying market price rent (46.9%) [

33].

More and more households had to face serious hardship to achieve a socially accepted level of housing consumption [

39,

42]. Affordability problems are, however, not limited to the poorest strata of society; they also affect many (lower) middle-class households [

20,

49], especially those who live in rental apartments.

3.2. The Hungarian Context: Welfare Regime

The welfare regime in Hungary underwent frequent changes in the preceding decades, with a most recent turn towards a system explicitly increasing inequalities. Hungary’s welfare regime showed a mixed character following the 1989/1990 transition, including measures reflecting neoliberal, social democratic, as well as conservative principles. The welfare system was also highly volatile, as successive governments frequently undid their predecessors’ social policies [

50]. Initial responses to the 2008 great financial crisis by the then-governing socialist government included drastic welfare cuts. Since 2010, when the right-wing conservative Orbán government took over governance, a significant and comprehensive reshaping of the welfare system has been ongoing, with a mixture of neoliberal, étatist, and neoconservative components [

51]. Welfare measures in the newly emerging system direct sources to better-off households, while cutting benefits for vulnerable households and distributing them on a meritocratic basis. Thereby, instead of alleviating inequalities, the current welfare regime widens the gap between different social groups and increases the vulnerability of disadvantaged households [

51].

As part of this turn, the length and level of unemployment benefits were drastically cut, and linked to behavior tests, and activation policies for unemployed people were almost totally replaced by a compulsory public work program. In addition, in family policy, a reverse redistribution was introduced, including generous family tax credits only available for employed parents, while freezing, and thereby devaluating, the amount of the universal child allowance [

52,

53].

The rearrangement of measures to tackle housing affordability problems also reflects this shift. In 2015, the provision of the central normative housing benefit and debt management was discontinued. Instead, the provision of support to ease affordability problems, and the setting of eligibility criteria, were placed under the discretion of local governments, which may or may not provide such support within the framework of their so-called ‘settlement subsidies.’ The change resulted in a highly fragmented system of services, leaving more space for arbitrary decisions [

42,

54,

55,

56]. In addition, the availability of support dramatically worsened, so that housing benefits became unavailable in around one-quarter of Hungarian settlements (especially smaller settlements), the amount of sources allocated to such purposes fell (to 55% of former budget allocations in 2016 compared to 2014), and the number of recipients sharply declined (by 44%) [

55].

The pension system was also rearranged, as a result of which, although the overall substitution rate improved, current pension levels became more dependent on labor market position and income and less dependent on compensation mechanisms based on solidarity [

52,

53].

At present, the Hungarian pension system relies mostly on a pay-as-you-go state pillar, with a small voluntary pillar (the private pillar was practically eliminated during the rearrangement of the pension system by the Orbán government in 2010–2011). Although the substitution rate of Hungarian pensions is not unfavorable [

57], due to the low purchasing power of Hungarian incomes, the purchase power of pensions is limited, as seen in the average European Union comparison [

58], with a mean consumption expenditure of 60% of the EU average in PPS ([

59] reference year: 2015). In the current Hungarian housing regime, this makes mortgage-free homeownership a more affordable and secure option, compared to other tenure forms [

36,

60]. However, in the current Hungarian housing regime, it is not characteristic for Hungarian households to downsize their housing consumption in older age; housing mobility research shows that the number of inhabited flats does not significantly increase for the over-50s cohort [

61,

62]; therefore, over-consumption of housing is frequent among older age groups, which leads to affordability problems, and imposes barriers to an asset-based welfare model [

12].

3.3. Is There a ‘Generation Rent’ in Hungary?

3.3.1. Trends of Young People’s Housing Tenure

The tenure structure of young adults has changed dramatically between 1999–2015 and is increasingly different from that of previous decades: the share of the PRS in younger households’ tenure structure (households with a household head aged up to 35 years) is rapidly increasing, with a parallel decrease in homeownership. While a realignment of the tenure structure, with a somewhat increasing PRS and decreasing owner-occupation rate, is a general trend in the Hungarian housing system, such changes are significantly more pronounced in the case of younger households. According to Housing Surveys of the Central Statistical Office [

36], the proportion of those living in private rentals multiplied by 2.6 between 1999 and 2015 in Hungary, from 3.1% to 8.1% of the total population. Among young households, the change was more dramatic (1999—10.2%; 2003—14.3; 2015—30.3%), while fewer people were affected among households with heads older than 35 years (1999—1.8%; 2015—4.9%) (

Figure 5). This change was accompanied by a similar decrease in the proportion of young households living in owner-occupied housing (1999—83.1%; 2003—81.1%; 2015—66.4%). Public rental housing plays a marginal role in all age groups, as the proportion of apartments reduced significantly and became extremely low (3%) [

63,

64].

The share of households living in private rentals among young households was the highest in Budapest in 2015 (37.7%). According to our survey (2017), 43.3% of the sample of young Budapest residents lived in PRS at some stage of their lives.

3.3.2. Attitudes concerning Rental and Owner-Occupied Housing

The mindset of young adults reflects the strong homeownership-orientation of the Hungarian society. Among the first words that came to mind for young respondents thinking about homeownership, ‘goal’ is the word that stands out. Other commonly used words referred to financing of homeownership (credit) and stability (safety, no rent) (

Figure 6). In contrast, the first words about rental apartments refer mainly to affordability problems (cost/expensive) and instability (state-owned/not mine).

According to our survey, 82.1% of young people think that tenants live in a rental apartment because they cannot afford to buy their own apartment, and only less than one in five believe that tenants choose this tenure because it suits their current life situation. Although the share is lower (65%) among those living in PRS, it is still high enough to signal attitudes towards private rental.

Young people with different housing experiences—those who currently reside in owner-occupied housing, and those who currently reside as tenants—show somewhat different attitudes towards renting and owner-occupation as tenure forms.

Tenants generally have more positive attitudes concerning rental housing. (

Figure 7.) They accept rental housing as a potentially long-term housing solution in a significantly higher proportion than young people in owner-occupied housing. They were also more likely to see advantages of rental housing, such as that renting opens up opportunities to live in apartments not available for them via purchase. They were more likely to accept tenancy as a suitable tenure form for young people before having children, and agree to that it is sufficient to purchase housing when they already know where they want to settle.

The importance of housing property is generally more pronounced among those who currently live in owner-occupied housing: they agreed more strongly that housing property provides security, and only owner-occupied housing provides a stable basis for child-raising (

Figure 8). Meanwhile, they are more likely to perceive tenancy as a vulnerable situation, as well as a financial loss (‘paying rent is lost money’). Interestingly, while those in the owner-occupied sector were more likely to think that obtaining housing property by the age of 35 is a sign of success in life, compared to tenants, such a statement did not generally receive high support among young people.

3.3.3. Housing Career Plans

On average, Hungarian young adults expect to get their own property by the age of 30. The 19–25-year-olds are more optimistic, feeling that they will be able to achieve this goal by the age of 27, while the 26–29-year-olds are already pushing the deadline to around the age of 34 [

58]. The main sources of property purchases are savings (58%), the different types of housing savings (64%), and housing loans (53%). Young people living in the capital and big cities, as well as those with higher education and a regular income, are more open to borrowing [

38]. Meanwhile, a significant proportion of young people do not have substantial savings that could be mobilized to buy a property. In addition to savings, having family support (40%) seems to be an essential requirement to obtain a property. On average, half of the amount spent on the purchase of a property comes from family help. Those who could not count on family support took on a larger loan (

Figure 9), but still spent a smaller amount on the purchase or had to go into the PRS [

38]. To obtain a larger loan, young people often have to take out multiple loans from different types of sources (i.e., personal and student loans) [

59]. Student loans in Hungary can be spent on any expense, without restriction. The majority of students spend 50% of their student loans on housing [

60].

In the survey, we asked young owners about the housing finance sources they used when they bought their housing property, as well as tenants about what housing finance resources they can count on for buying housing property in the future. Among owners, the proportion of those who could count on non-refundable family help is more than twice as high (37.2%) as among tenants; only 15.8% of the latter can count on such help with a future purchase. The same applies to refundable family loans (owners—47.8%; tenants—24.6%). Compared to state subsidies, bank loans play a more important role in the home purchase portfolio of young families. Among both owners and tenants, the proportion of those who (would) take out bank loans is almost twice as high compared to those who count on government support. (owners–60.9% and 32.5%; tenants—66.1% and 38.5%, respectively) (

Figure 10).

Most interviewed young people are planning to pursue owner-occupied housing in their future housing careers. Owner-occupied housing appears as a housing career goal, even for low-income young people with realistically weak chances for home acquisition. Some of them plan to take the non-refundable state subsidy for home purchase or construction (only available for households with children, and couples who contractually commit themselves to undertake having children); however, the lack of other sources of financing may divert their housing careers to economically less advantaged areas, with lower property prices. Many of them explicitly expressed that they view state subsidies as supports targeted for the better-off. Meanwhile, the rental sector, including (mostly) the PRS, is present as a longer-term housing solution in the housing career plans of some young people. Among young residents in the PRS, 44% found it somewhat or totally imaginable that they will rent for longer periods, perhaps even decades.

Disparities between young people in terms of home acquisition chances are shown by the fact that children of non-owners are less likely to possess housing property. Of those whose parents are homeowners, 37.5% are homeowners themselves. Out of those whose parents are not homeowners, this rate is 25% (

Figure 11).

In investigating ’generation rent,’ the changing patterns of youth-adulthood transition should also be considered. The process of the transition to adulthood has lengthened. Lately, more and more people are living with their parents, even in their twenties and thirties [

65,

66]. The proportion of these young people (aged 18–34) in Hungary increased by 12% between 2005 (50%) and 2019 (62%) [

67]. The main reasons are lengthened study time, deferred family formation, unstable or poor job market opportunities or poor financial situation, and lack of family financial support. Young people’s financial independence and leaving the parental home (at 26.2 years on average) are closely related to the time at which they take up employment [

68,

69,

70]. At the same time, employment is not always enough to start an independent life, if the salary is insufficient for rent and housing costs, or if a mortgage deposit has to be saved. To stay home could mean to save money [

71]. For this reason, it is likely that the size of the ‘generation rent’ would be even larger, if we include young adults living with parents without any chance to enter private rental housing (affordability problems) or social housing (availability). Under such circumstances, moving out of the parental home could increase the risk of falling into poverty [

72]. Therefore, the remaining options for low income young households include family-based arrangements and ultimately, when all other solutions fail, the predominantly institutionalized care system for homeless people. Low-status households often fluctuate between inadequate housing solutions in these segments of the housing market, without realistic chances to obtain adequate housing.

With the lack of a sufficiently operating social housing sector, the private rental sector is one of the only options for many households. [

34] The accumulation of low-income households, including low income young households, in the private rental sector is one of the reasons behind the expansion of this sector. The increasing need for housing opportunities in the PRS by low income households (including young households) contributes to the growth of a ‘low-end’ segment of the private rental housing market, with sometimes extreme inadequacy problems and very poor price-to-value ratio (‘usury tenements,’ as labelled by Ámon and Balogi [

73]).

4. Discussion

Trends in young people’s housing tenure show an increasing role of the PRS compared to earlier young generations’ housing tenure, as well as older generations’ tenure structure. Moreover, rental housing appears as a potential long-term solution in the attitudes of young people, especially those who currently reside in the PRS.

Meanwhile, homeownership appears as a goal in most Hungarian young people’s housing career plans, reflecting the strongly ownership-oriented policy of the government and public discourse. Many low-income young people pursue this goal, even though their chances to obtain homeownership, especially owner-occupied housing offering adequate housing conditions, are poor; thereby, such a housing career plan seems to reflect a ‘fallacy of choice’ [

27].

The housing regime plays an important part in the development of a Hungarian ‘generation rent’. Intergenerational transfers play a major role in the housing trajectories of young Hungarians; therefore, social inequalities reproduce across generations [

38,

43,

74]. Such inequalities are amplified by the uneven access to state subsidies, given that a major subsidy scheme’s eligibility criteria is linked to the possession of a predefined date of social security, non-refundable subsidies require additional housing finance sources to acquire homeownership—which low-status households are less likely to be able to obtain— the level of subsidies available for used housing—the only realistic option for households with limited resources—are lower compared to those for new housing, and state-subsidized loans are only available for creditworthy households.

As a result, higher status young people have better chances for accessing the ownership sector right after leaving the family home, or moving on to the owner-occupied sector after the PRS. Meanwhile, young people without intergenerational support, along with low income (due to lack of access to the labor market, precarious employment situations, and/or employment in poorly paid sectors) have systematically poorer chances to access state subsidies and obtain owner-occupied housing, especially in areas with good labor market opportunities and thus, higher property prices [

38].

In addition to the development of a Hungarian ‘generation rent’, housing policies also affect the housing experiences of PRS residents. Loose regulation and the lack of an effective system of dispute resolution and law enforcement leads to severe tenure security and affordability problems. Meanwhile, there is no comprehensive system of housing benefits to support the running costs of housing. Placing the regulation and provision of housing benefits—to support households in covering the running costs of housing—on local governments drastically decreased the availability and increased inequalities in accessing such support, amplifying the vulnerability of affected low income households. Housing benefits for the running costs of housing became unavailable in around one-quarter of Hungarian settlements, especially smaller ones, the amount of sources allocated for such purposes, and the number of recipients dramatically declined, and a highly fragmented system developed, with more opportunity for arbitrary decisions [

55]. In order to reduce tenure security and affordability risks, many households turn to family and friend networks; therefore, ‘generation rent’ households in Hungary often live in the intersection of housing market segments, coordinated by market and reciprocity mechanisms [

15]. Such hybrid housing arrangements may take several forms. However, the involvement of family relations tends to prolong dependency on the family, thus affecting youth to adulthood transition. Such hybrid housing forms may be classified as semi-independent housing [

10], where de-cohabitation does not run parallel to de facto residential independence.

In addition, young people from different social backgrounds access different segments of the rental sector, with low-status young people often having access only to the ‘low-end’ segment of the market. Therefore, we need to pay more attention in future research to the internal heterogeneity of ‘generation rent’ in terms of social status, the factors behind housing choices, and housing outcomes in the rental sector, especially the private rental sector.

While the PRS appears in the planned housing trajectories of many young people from different social backgrounds, factors behind this vary. While higher status young households may choose the PRS as a longer-term housing option to achieve more freedom and flexibility, low-status young households may end up in the PRS because of the lack of any other housing solutions [

73].

Meanwhile, the increasing ownership-orientation of housing policies and the fact that they obtained center stage in the government’s ’better-off’ focused family policy (which became the flagship political issue promoted by the Orbán government) is likely to have a socially disproportionate effect on young households’ housing trajectories. Such an effect will also be mediated by the development of property prices, which are not unrelated to the increasing amount of government subsidies in the housing market. As a result, housing disparities between better-off young households able to access adequate owner-occupied housing and low-status young households, without such a chance is likely to increase. The PRS, and specifically the lower end of the PRS, remains the only option for independent living for many of the lower-status young households.

5. Conclusions

Our article examined whether ’generation rent,’ a concept developed in a Western context, more specifically, in Anglo-Saxon housing literature, is applicable to understand young people’s housing tenure experiences and prospects in a significantly different setting. Our context is contemporary Hungary, with its ‘super-homeownership’ housing system, policies, and policy discourse.

The available data suggest that the concept can be applied in the Hungarian context: trends in young people’s housing tenure show a significantly increased role of the PRS compared to earlier young generation’s housing tenure, and the tenure structure of other age groups, and the role of rental housing as a potentially long-term housing solution is present in young people’s attitudes concerning housing. Meanwhile, young people’s housing career plans reflect the strong ownership-orientation of the Hungarian housing regime and public discourse: most interviewed young people pursue owner-occupied housing in their future housing careers, including low-income young people with realistically weak chances of home acquisition.

The development, housing experiences, as well as housing career plans of ‘generation rent’ in Hungary, are strongly influenced by the specific welfare regime and housing system context. Along with the strong role of intergenerational transfers, public housing policies contribute to the development of a ‘generation rent’ in Hungary through different mechanisms, such as the development of a system of housing subsidies systematically more accessible for higher status households and a lack of policy measures to develop a well-functioning social housing sector. Housing policies influence the housing experiences of a Hungarian ‘generation rent’ through tenure insecurity and affordability problems caused by the loose regulation of the rental sector, the lack of an effective system of dispute resolution and law enforcement, as well as a lack of a comprehensive system of housing benefits.

Further development of a ‘generation rent’ in Hungary, in the sense of a generation which might proceed to later life stages without access to homeownership [

29], is also likely to be context-specific. Due to the laissez-faire regulation of the rental sector and the lack of an effective system of legal support, landlords often discriminate against households with children, as they perceive them as risky tenants, which narrows the opportunities for such households in the PRS and may push them out to other sectors of the housing market.

It seems that there is an internal heterogeneity of ‘generation rent’, with different housing trajectories, especially in the private rental sector. Therefore, in future research, we need to pay more attention to the internal heterogeneity of ‘generation rent’ in terms of social status, the factors behind housing choices, and housing outcomes in the rental sector, especially the PRS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and L.K.; methodology, A.C.; formal analysis, A.C. and L.K.; investigation, A.C.; resources, A.C.; data curation, A.C. and L.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C. and L.K.; writing—review and editing, A.C. and L.K.; visualization, A.C. and L.K.; supervision, A.C.; project administration, A.C.; funding acquisition, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office—NKFIH-K109333. The research was carried out in cooperation with CSS and the Metropolitan Research Institute, Budapest, Hungary. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 956082 RE-DWELL,

https://www.re-dwell.eu/, accessed on 13 July 2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Center for Social Sciences.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The survey data presented in this study are stored at the Digital Repository Center of the Center for Social Sciences (Hungarian Academy of Sciences Center of Excellence, Eötvös Loránd Research Network), which archives the data of research projects conducted at the center (

http://openarchive.tk.mta.hu, accessed on 13 July 2022).

Acknowledgments

The word cloud was prepared with the help of Botond Palaczki.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bricocoli, M.; Sabatinelli, S. House Sharing amongst Young Adults in the Context of Mediterranean Welfare: The Case of Milan. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2016, 16, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filandri, M.; Bertolini, S. Young People and Home Ownership in Europe. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2016, 16, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, A. Rental Subsidy and the Emancipation of Young Adults in Spain. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2016, 16, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.J.; Hoekstra, J.S.C.M.; Elsinga, M.G. The Changing Determinants of Homeownership amongst Young People in Urban China. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2016, 16, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Castro Campos, B.; Yiu, C.Y.; Shen, J.; Liao, K.H.; Maing, M. The Anticipated Housing Pathways to Homeownership of Young People in Hong Kong. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2016, 16, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald, R. ‘Generation Rent’ and Intergenerational Relations in The Era of Housing Financialisation. Crit. Hous. Anal. 2018, 5, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, M.; Gibas, P.; Boumová, I.; Hájek, M.; Sunega, P. Reasoning behind Choices: Rationality and Social Norms in the Housing Market Behaviour of First-Time Buyers in the Czech Republic. Hous. Stud. 2017, 32, 517–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csizmady, A.; Hegedüs, J.; Nagy, G. The Effect of GFC on Tenure Choice in a Post-Socialist Country—The Case of Hungary. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2017, 17, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellandini-Simányi, L.; Banai, A. The Conformity-Risk Paradox: Why Increasingly Risky Mortgages Are Acquired By Increasingly Risk-Averse Consumers. ACR N. Am. Adv. 2017, 45, 809–811. [Google Scholar]

- Arundel, R.; Ronald, R. Parental Co-Residence, Shared Living and Emerging Adulthood in Europe: Semi-Dependent Housing across Welfare Regime and Housing System Contexts. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 19, 885–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandic, S. Home-Leaving and Its Structural Determinants in Western and Eastern Europe: An Exploratory Study. Hous. Stud. 2008, 23, 615–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, K. Young People, Homeownership and Future Welfare. Hous. Stud. 2012, 27, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoolachan, J.; McKee, K.; Moore, T.; Soaita, A.M. ‘Generation Rent’ and the Ability to ‘Settle down’: Economic and Geographical Variation in Young People’s Housing Transitions. J. Youth Stud. 2017, 20, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.T.O. Intergenerational Family Support for ‘Generation Rent’: The Family Home for Socially Disengaged Young People. Hous. Stud. 2019, 34, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedüs, J. Understanding Housing Development in New European Member States—A Housing Regime Approach. Crit. Hous. Anal. 2020, 7, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald, R.; Kadi, J. The Revival of Private Landlords in Britain’s Post-Homeownership Society. New Political Econ. 2018, 23, 786–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, I.; Powell, R.; Sanderson, E. Putting the Squeeze on ‘Generation Rent’: Housing Benefit Claimants in the Private Rented Sector—Transitions, Marginality and Stigmatisation. Sociol. Res. Online 2016, 21, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyák, L. Rákóczi Collective—Alternatives to Individual Homeownership 2017. Available online: https://cooperativecity.org/2017/10/03/rakoczi-collective/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Kemeny, J. The Myth of Home-Ownership: Private versus Public Choices in Housing Tenure; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1981; ISBN 978-0-7100-0634-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pósfai, Z.; Jelinek, C. Reproducing Socio-Spatial Unevenness Through the Institutional Logic of Dual Housing Policies in Hungary. In Regional and Local Development in Times of Polarisation; Lang, T., Görmar, F., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 197–223. ISBN 9789811311895. [Google Scholar]

- Clapham, D. Housing Pathways: A Post Modern Analytical Framework. Hous. Theory Soc. 2002, 19, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugg, J. Young People and Housing: The Need for a New Policy Agenda. Available online: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/young-people-and-housing-need-new-policy-agenda (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Blackwell, A.; Park, A. The Reality of Generation Rent: Perceptions of the First Time Buyer Market; The British Library: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, K. Definition of Generation Rent, BuzzWord from Macmillan Dictionary. Available online: https://www.macmillandictionary.com/buzzword/entries/generation-rent.html (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Rugg, J.; Quilgars, D. Young People and Housing: A Review of the Present Policy and Practice Landscape. Youth Policy 2015, 114, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, P.A. Private Renting After the Global Financial Crisis. Hous. Stud. 2015, 30, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, K. Briefing No 6. Young People, Homeownership and the Fallacy of Choice; University of St Andrews: St Andrews, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, K.; Hoolachan, J. Housing Generation Rent: What Are the Challenges Facing Housing Policy in Scotland? University of St Andrews: St Andrews, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Santos, R. Homes Fit for Families—The Case for Stable Private Renting. Available online: https://england.shelter.org.uk/professional_resources/policy_and_research/policy_library/policy_briefing_homes_fit_for_families_-_the_case_for_stable_private_renting (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Lennartz, C.; Arundel, R.; Ronald, R. Younger Adults and Homeownership in Europe Through the Global Financial Crisis: Young People and Homeownership in Europe Through the GFC. Popul. Space Place 2016, 22, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedüs, J.; Teller, N. Managing Risks in the New Housing Regimes of the Transition Countries-The Case of Hungary. In Home Ownership: Getting in, Getting from, Getting Out, Part II; Doling, J., Elsinga, M.G., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 175–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hegedüs, J. Social Housing in Post-Crisis Hungary,: A Reshaping of the Housing Regime under ‘Unorthodox’ Economic and Social Policy. Crit. Hous. Anal. 2017, 4, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distribution of Population by Tenure Status, 2018 (%). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Distribution_of_population_by_tenure_status,_2018_(%25)_SILC20.png (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Hegedüs, J.; Horváth, V.; Lux, M. Central and East European Housing Regimes in the Light of Private Renting. In Private Rental Housing in Transition Countries; Hegedüs, J., Lux, M., Horváth, V., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2018; pp. 387–411. ISBN 978-1-137-50709-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lakásviszonyok az Ezredfordulón [Housing Conditions at the Turn of the Millennium]; KSH (Central Statistical Office, Hungary): Budapest, Hungary, 2005.

- Dóra, I.; Hegedüs, J.; Horváth, Á.; Sápi, Z.; Somogyi, E.; Székely, G. Miben Élünk? A 2015. Évi Lakásfelmérés Főbb Eredményei [What Do We Live in? Main Results of the Housing Survey 2015; KSH (Central Statistical Office, Hungary): Budapest, Hungary, 2016.

- Kováts, B. A Magánbérlakás-Rendszer Szabályozása Magyarországon. [Regulation of the Private Rental Housing System in Hungary]. In A Megfizethető Bérlakásszektor Felé; Habitat for Humanity Hungary—Solid Ground: Budapest, Hungary, 2017; pp. 8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, J.; Szemzo, H.; Elsinga, M.; Hegedüs, J.; Teller, N. Owner-Occupation, Mortgages and Intergenerational Transfers: The Extreme Cases of Hungary, and the Netherlands. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2012, 12, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedüs, J. Housing Privatization and Restitution in Post-Socialist Countries. In Social Housing in Transition Countries; Hegedüs, J., Lux, M., Teller, N., Eds.; Routledge Studies in Health and Social Welfare; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 33–49. ISBN 978-0-415-89014-4. [Google Scholar]

- József, H.; Teller, N. Escape into Homeownership in: Homeownership beyond Asset and Security. In Homeownership Beyond Asset and Security; Elsinga, M., Decker, P., Teller, N., Toussaint, J., Eds.; Housing and Urban Policy Studies; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 133–172. [Google Scholar]

- Átol, D.; Kováts, B.; Kőszeghy, L. Éves Jelentés a Lakhatási Szegénységről 2015 [Annual Report on Housing Poverty]; Annual Report on Housing Poverty; Habitat for Humanity Hungary: Budapest, Hungary, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Átol, D.; Bozsik, B.; Kováts, B.; Kőszeghy, L. Éves Jelentés a Lakhatási Szegénységről 2016 [Annual Report on Housing Poverty]; Annual Report on Housing Poverty; Habitat for Humanity Hungary: Budapest, Hungary, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pósfai, Z.; Gál, Z.; Nagy, E. Financialization and Inequalities: The Uneven Development of the Housing Market on the Eastern Periphery of Europe. In Inequality and Uneven Development in the Post-Crisis World; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 167–190. [Google Scholar]

- Egy Lakás átlagos Négyzetméterára Régió és Településtípus Szerint [Ezer Forint] [Average Price per Square Meter by Statistical Region and Settlement Type (Thousand HUF)]. Available online: https://www.ksh.hu/stadat_files/lak/hu/lak0025.html (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Fellner, Z.; Bereczki, Á.; Kovalszky, Z.; Winkler, S. Lakáspiaci Jelentés 2018. [Housing Market Report]; Magyar Nemzeti Bank: Budapest, Hungary, 2018; Volume 5, ISSN 2498-6704. [Google Scholar]

- Lakáspiaci Árindex 2010–2021 [Housing Market Price Index]. Available online: https://www.ksh.hu/stadat_files/lak/hu/lak0013.html (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Lakbérindex-Számítás 2015–2020 [Rent Index Calculation]. Available online: https://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/stattukor/lakberindex_szamitas/index.html (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Hegedüs, J.; Somogyi, E. A lakások megfizethetősége és a társadalmi egyenlőtlenségek [Affordability of housing and social inequalities]. In Miben Élünk? A 2015. Évi Lakásfelmérés Részletes Eredményei [What Do We Live in? Detailed Results of the 2015 Housing Survey]; KSH (Central Statistical Office, Hungary): Budapest, Hungary, 2018; pp. 6–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jelinek, C. Költségvetési kiadások és közolitikai változások [Budget expenditure and public policy changes]. In Éves Jelentés a Lakhatási Szegénységről 2019. [Annual Report on Housing Poverty]; Habitat for Humanity Hungary: Budapest, Hungary, 2020; pp. 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tomka, B.; Szikra, D. Social Policy in East Central Europe: Major Trends in the 20th Century. In PostCommunist Welfare Pathways: Theorizing Social Policy Transformations in Central and Eastern Europe; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009; pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Szikra, D. Democracy and Welfare in Hard Times: The Social Policy of the Orbán Government in Hungary, between 2010 and 2014. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2014, 24, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szikra, D. Távolodás Az Európai Szociális Modelltől—A Szegénység Társadalompolitikája. [Distancing from the European Social Model—The Social Policy of Poverty]. Magy. Tudomány 2018, 179, 858–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szikra, D. Welfare for the Wealthy: The Social Policy of the Orbán-Regime, 2010–2017; Analysis; Fridriech Ebert Stiftung: Budapest, Hungary, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Czirfusz, M.; Jelinek, C.S. Lakhatási Közpolitikák, és a Lakhatás Megfizethetősége az Elmúlt Három Évtizedben [Housing Policies and the Affordability of Housing in the Last Three Decades]. In Éves Jelentés a Lakhatási Szegénységről 2021. [Annual Report on Housing Poverty]; Habitat for Humanity Hungary: Budapest, Hungary, 2022; Available online: https://habitat.hu/sites/lakhatasi-jelentes-2021/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2021/11/FINAL_Habitat_EvesJelentes_2021-3_20211109.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Kopasz, M.; Gábos, A. A Szociális Segélyezési Rendszer 2015. Márciusi Átalakításának Hatása a Települési Önkormányzatok Magatartására [The Impact of the March 2015 Reform of the Welfare System on the Behavior of Local Government]. In Társadalmi Riport 2018; Kolosi, T., Tóth, I.G., Eds.; Tárki Zrt: Budapest, Hungary, 2018; pp. 328–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kováts, B. Rezsitámogatás-csökkentés. [Reduction of utility cost subsidies]. Esély 2015, 6, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Szikra, D. A Magyar Nyugdíjrendszer a Rendszerváltás Óta. [The Hungarian Pension System since the Change of Regime]. In Magyar Társadalom- és Szociálpolitika (1990–2015) [Hungarian Social Policy]; Ferge, Z., Ed.; Osiris: Budapest, Hungary, 2017; pp. 215–254. [Google Scholar]

- Aggregate Replacement Ratio for Pensions (Excluding Other Social Benefits) by Sex—EU-SILC Survey. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ilc_pnp3/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Mean Consumption Expenditure by Socio-Economic Category of the Reference Person. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/HBS_EXP_T131__custom_2990379/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Hegedüs, J.; Horváth, V.; Tosics, N. Economic and Legal Conflicts between Landlords and Tenants in the Hungarian Private Rental Sector. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2014, 14, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- József, H. Lakásmobilitás a magyar lakásrendszerben [Housing mobility in the Hungarian housing system]. Stat. Szle. 2001, 79, 934–954. [Google Scholar]

- Csizmady, A.; Kőszeghy, L.; Győri, Á. Lakásmobilitás, Társadalmi Pozíciók És Integrációs Csoportok [Housing Mobility, Social Positions and Integration Groups]. Socio. Hu 2019, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Háztartások Életszínvonala, 2019 [Standard of Living of Households]. Available online: https://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/idoszaki/hazteletszinv/2019/index.html#ahztartsokfogyasztsikiadsainaknagysgaszerkezete (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Miből Vesznek Lakást a Fiatalok? [From What Source do Young People Buy Housing?]. Available online: https://piacesprofit.hu/tarsadalom/mibol-vesznek-lakast-a-fiatalok/ (accessed on 27 June 2022).

- Billari, F.C.; Liefbroer, A.C. Towards a New Pattern of Transition to Adulthood? Adv. Life Course Res. 2010, 15, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzinga, C.H.; Liefbroer, A.C. De-Standardization of Family-Life Trajectories of Young Adults: A Cross-National Comparison Using Sequence Analysis: Dé-Standardisation Des Trajectoires de Vie Familiale Des Jeunes Adultes: Comparaison Entre Pays Par Analyse Séquentielle. Eur. J. Popul. 2007, 23, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Share of Young Adults Aged 18-34 Living with Their Parents by Age and Sex—EU-SILC Survey. Available online: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?lang=en&dataset=ilc_lvps08 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Murinkó, L. Pathways, Background and Outcomes of the Transition to Adulthood in the Early 2000s in Hungary. Demogr. Engl. Ed. 2020, 61, 59–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medgyesi, M.; Nagy, I. Fiatalok életkörülményei Magyarországon és az EU országaiban 2007 és 2012 között [Life circumstances of the youth in Hungary, and the EU countries between 2007 and 2012]. In Társadalmi Riport 2014; Kolosi, T., Tóth, I.G., Eds.; Tárki Zrt: Budapest, Hungary, 2014; pp. 303–323. [Google Scholar]

- Gazsó, T. Munkaerő-piaci helyzetkép. [Labor market report]. In Magyar Ifjúság 2012. Tanulmánykötet; Székely, L., Ed.; Kutatópont: Budapest, Hungary, 2013; pp. 127–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ayllón, S. Youth Poverty, Employment, and Leaving the Parental Home in Europe. Rev. Income Wealth 2015, 61, 651–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aassve, A.; Iacovou, M.; Mencarini, L. Youth Poverty and Transition to Adulthood in Europe. Demogr. Res. 2006, 15, 21–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ámon, K.; Balogi, A. A Magánbérleti Piac Alsó Szegmense [The Lower Segment of the Private Rental Market]. Available online: https://www.habitat.hu/mivel-foglalkozunk/lakhatasi-jelentesek/lakhatasi-jelentes-2018/alberletek-also-szegmense/ (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Hegedüs, J.; Somogyi, E.; Teller, N. Lakáspiac És Lakásindikátorok. [Housing Market and Housing Indicators]. In Társadalmi Riport 2018 [Social Report]; Kolosi, T., Tóth, I.G., Eds.; Tárki Zrt: Budapest, Hungary, 2018; pp. 309–327. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).