How Live Streaming Interactions and Their Visual Stimuli Affect Users’ Sustained Engagement Behaviour—A Comparative Experiment Using Live and Virtual Live Streaming

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Can visual stimuli that convey emotions (e.g., emojis) influence the emotional connection between users of live streaming?

- Can the social engagement behaviour of live streaming users influence their intention of continuous engagement?

- Will the form of the anchor make a difference to the influencing factors identified?

2. Literature Review

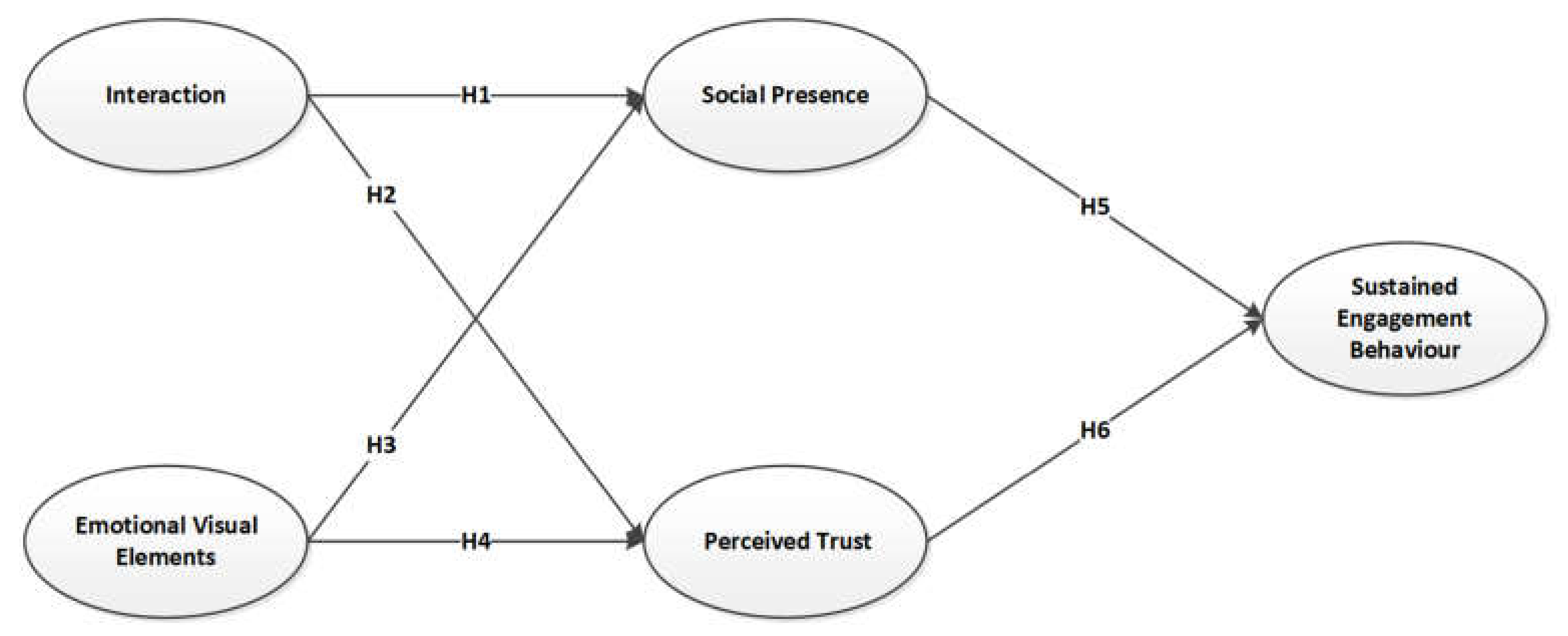

3. Hypothesis Development

4. Research Method

4.1. Experimental Design

4.2. Sample Selection

5. Results

5.1. Measurement Models

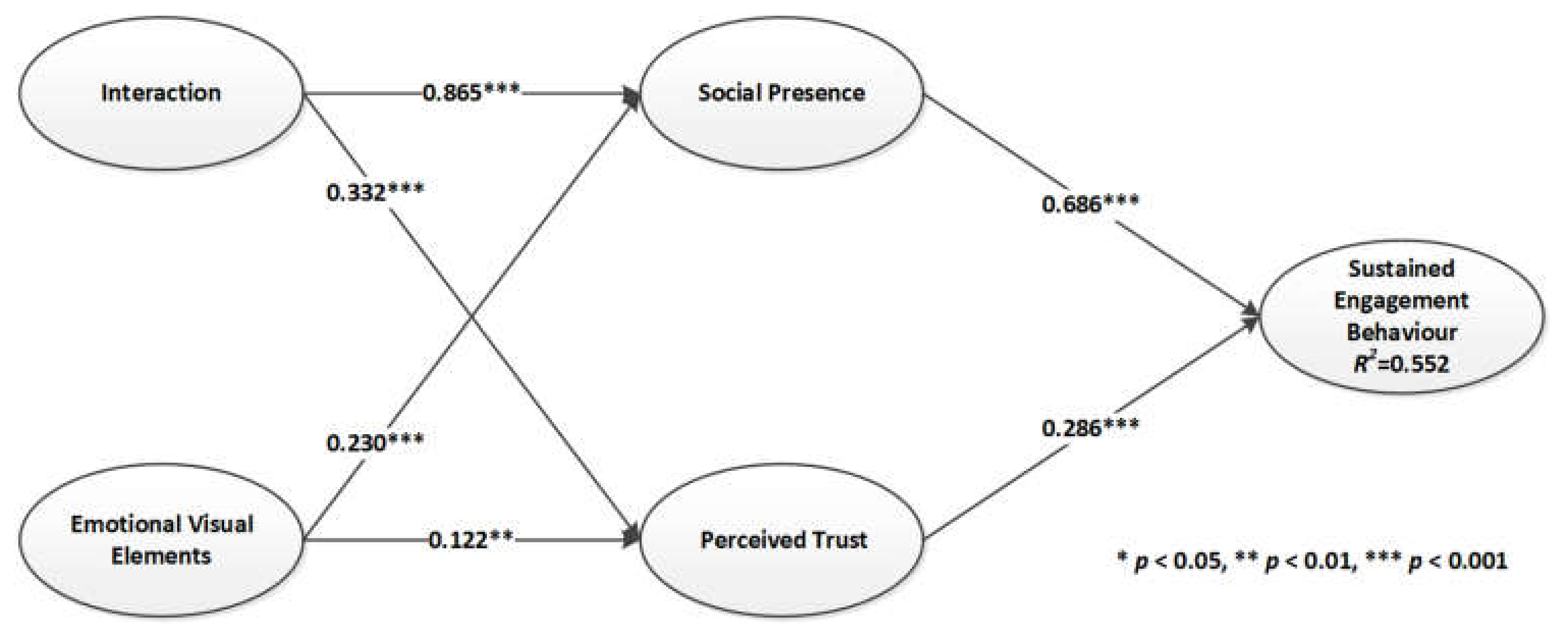

5.2. Structural Model

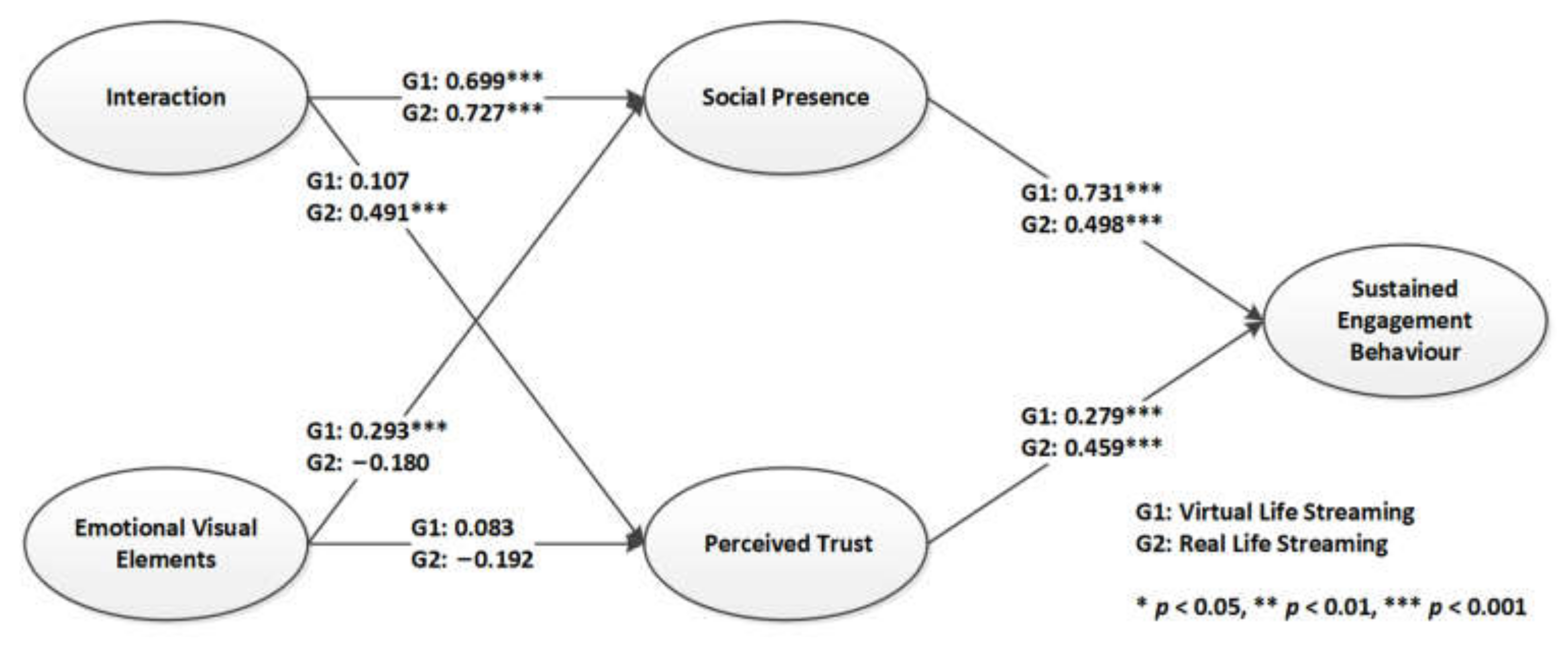

5.3. Multi-Group Analysis

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.2. Limitation and Future Work

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurement Items

| Construct | Item | References |

|---|---|---|

| INT | When watching a live-stream, I will exchange and share opinions with the streamer or other audiences. | [5,18] |

| When watching a live-stream, I interacted with other viewers using the hashtags related to the live streaming. | ||

| When watching a live-stream, I posted my feelings in real-time online conversation. | ||

| When watching a live-stream, I will answer questions from the anchor and other viewers. | ||

| EVE | The interactive content in the live interface is visually appealing. | [41] |

| The interactive content in the live interface is visually pleasing. | ||

| The interactive content in the live interface is visually cheerful. | ||

| The interactive content in the live interface is visually interesting. | ||

| PTR | Promises made by this live streaming are likely to be reliable. | [20,48] |

| I do not doubt the honesty of this live streaming. | ||

| Based on my experience with this live streaming, I know it is honest. | ||

| I feel that this live streaming is trustworthy. | ||

| SPR | When I participate in a live-streaming chat, I feel emotionally connected with users I am chatting with. | [6,48] |

| There is a sense of human contact on this live streaming. | ||

| There is a sense of sociability on this live streaming. | ||

| There is a sense of human warmth on this live streaming. | ||

| SEB | I feel more attached to my favorite live-streaming channels than other channels. | [6] |

| I will continue to watch my favorite live-streaming channel. | ||

| I will increase the amount of time I spend watching my favorite live-streaming channel. | ||

| I consider myself to be a committed fan of my favorite live-streaming channel. |

References

- Ma, L.; Gao, S.; Zhang, X. How to Use Live Streaming to Improve Consumer Purchase Intentions: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.; Jung, C.; Kim, H.; Jung, J. Impact of viewer engagement on gift-giving in live video streaming. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, H. The computer-mediated communication network: Exploring the linkage between the online community and social capital. New Media Soc. 2010, 12, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Chen, L.Y.; Su, Q.L. Understanding the impact of social distance on users’ broadcasting intention on live streaming platforms: A lens of the challenge hindrance stress perspective. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 41, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-C. What drives live-stream usage intention? The perspectives of flow, entertainment, social interaction, and endorsement. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Choe, M.-J.; Zhang, J.; Noh, G.-Y. The role of wishful identification, emotional engagement, and parasocial relationships in repeated viewing of live-streaming games: A social cognitive theory perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Shen, C.; Li, J.; Shen, H.; Wigdor, D. More Kawaii than a Real-Person Live Streamer: Understanding How the Otaku Community Engages with and Perceives Virtual YouTubers. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 7 May 2021; p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.H. The Research on Applying Artificial Intelligence Technology to Virtual YouTuber. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics, Automation and Artificial Intelligence (RAAI), Hong Kong, China, 21–23 April 2021; pp. 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, R.M.M.I.; Olsen, G.D.; Pracejus, J.W. Affective Responses to Images in Print Advertising: Affect Integration in a Simultaneous Presentation Context. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Stoel, L.; Lennon, S.J. Cognitive, affective and conative responses to visual simulation: The effects of rotation in online product presentation. J. Consum. Behav. 2008, 7, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, A.; Adolphs, R. Emotion Perception from Face, Voice, and Touch: Comparisons and Convergence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2017, 21, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fiore, A.M.; Yu, H. Effects of imagery copy and product samples on responses toward the product. J. Interact. Mark. 2001, 15, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.H.; Tseng, T.H. Playfulness in mobile instant messaging: Examining the influence of emoticons and text messaging on social interaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, T.E. Uses and Gratifications Theory in the 21st Century. Mass Commun. Soc. 2000, 3, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheung, G.; Huang, J. Starcraft from the stands: Understanding the game spectator. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–11 May 2011; pp. 763–772. [Google Scholar]

- Hilvert-Bruce, Z.; Neill, J.T.; Sjöblom, M.; Hamari, J. Social motivations of live-streaming viewer engagement on Twitch. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, C.W.; Young, S.M. Consumer Response to Television Commercials: The Impact of Involvement and Background Music on Brand Attitude Formation. J. Mark. Res. 1986, 23, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Hwang, Y.; Kim, S.; Biocca, F.A. How social media engagement leads to sports channel loyalty: Mediating roles of social presence and channel commitment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 46, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.C.; Byon, K.K.; Jang, W.; Ma, S.M.; Huang, T.N. Esports Spectating Motives and Streaming Consumption: Moderating Effect of Game Genres and Live-Streaming Types. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N.; Sims, J.; Zadeh, A.H.; Richard, M.-O. A social commerce investigation of the role of trust in a social networking site on purchase intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 71, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blattberg, R.C.; Sen, S.K. Market Segmentation Using Models of Multidimensional Purchasing Behavior: A new segmentation strategy designed to provide better information to the marketing decision maker. J. Mark. 1974, 38, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.S.; Anderson, R.; Ponnavolu, K. Customer loyalty in e-commerce: An exploration of its antecedents and consequences. J. Retail. 2002, 78, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Day, G.S. A Two-Dimensional Concept of Brand Loyalty. In Mathematical Models in Marketing: A Collection of Abstracts; Funke, U.H., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1976; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, A.S.; Basu, K. Customer Loyalty: Toward an Integrated Conceptual Framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1994, 22, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Martell, M. Does attitudinal loyalty influence behavioral loyalty? A theoretical and empirical study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2007, 14, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthi, L.; Raj, S.P. An Empirical Analysis of the Relationship between Brand Loyalty and Consumer Price Elasticity. Mark. Sci. 1991, 10, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Qi, Y.; Li, X. What affects the user stickiness of the mainstream media websites in China? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 29, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulk, J.; Steinfield, C.W.; Schmitz, J.; Power, J.G. A Social Information Processing Model of Media Use in Organizations. Commun. Res. 1987, 14, 529–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piller, F.T.; Walcher, D. Toolkits for idea competitions: A novel method to integrate users in new product development. R&D Manag. 2006, 36, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruikemeier, S.; van Noort, G.; Vliegenthart, R.; de Vreese, C.H. Getting closer: The effects of personalized and interactive online political communication. Eur. J. Commun. 2013, 28, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brockmyer, J.H.; Fox, C.M.; Curtiss, K.A.; McBroom, E.; Burkhart, K.M.; Pidruzny, J.N. The development of the Game Engagement Questionnaire: A measure of engagement in video game-playing. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.-H. Do Users Experience Real Sociability through Social TV? Analyzing Parasocial Behavior in Relation to Social TV. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2016, 60, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Kwon, S.J. The Effects of Customers’ Mobile Experience and Technical Support on the Intention to Use Mobile Banking. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D. E-commerce: The role of familiarity and trust. Omega 2000, 28, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.W. Consumer trust in B2C e-Commerce and the importance of social presence: Experiments in e-Products and e-Services. Omega 2004, 32, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-H.; Ju, T.L.; Yen, C.-H.; Chang, C.-M. Knowledge sharing behavior in virtual communities: The relationship between trust, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations. Int. J. Hum. Comput. 2007, 65, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Chang, Y.S. Towards understanding members’ interactivity, trust, and flow in online travel community. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2005, 105, 937–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Rashid, R.M.; Wang, J. Investigating the role of social presence dimensions and information support on consumers’ trust and shopping intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schau, H.J.; Muñiz, A.M.; Arnould, E.J. How Brand Community Practices Create Value. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.-P.; Turban, E. Introduction to the Special Issue Social Commerce: A Research Framework for Social Commerce. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Wu, S. The impacts of technological environments and co-creation experiences on customer participation. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Harper, F.M.; Drenner, S.; Terveen, L.; Kiesler, S.; Riedl, J.; Kraut, R.E. Building Member Attachment in Online Communities: Applying Theories of Group Identity and Interpersonal Bonds. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 841–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenburg, P.M.; Peter, J.; Schouten, A.P. Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.-H.; Choi, S.M. MINI-lovers, maxi-mouths: An investigation of antecedents to eWOM intention among brand community members. J. Mark. Commun. 2011, 17, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, M.; Spears, R. Paralanguage and social perception in computer-mediated communication. J. Organ. Comput. 1992, 2, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogg, B.J. Persuasive technology: Using computers to change what we think and do. Ubiquity 2002, 2002, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riegelsberger, J.; Sasse, M.A.; McCarthy, J.D. Shiny happy people building trust? Photos on e-commerce websites and consumer trust. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 5–10 April 2003; pp. 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanein, K.; Head, M. Manipulating perceived social presence through the web interface and its impact on attitude towards online shopping. Int. J. Hum. Comput. 2007, 65, 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Chen, L.; Wen, C.; Prybutok, V.R. Co-viewing Experience in Video Websites: The Effect of Social Presence on E-Loyalty. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2018, 22, 446–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, W.; Khani, A.H.; Schultz, C.D.; Adam, N.A.; Attar, R.W.; Hajli, N. How social presence drives commitment and loyalty with online brand communities? The role of social commerce trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.K.; Chiu, P.-Y.; Lee, M.K.O. Online social networks: Why do students use facebook? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.B.; Cho, H. The impact of consumer trust on attitudinal loyalty and purchase intentions in B2C e-marketplaces: Intermediary trust vs. seller trust. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G.; O’Connor, P.; El-Haddad, R. Examining an integrated model of green image, perceived quality, satisfaction, trust, and loyalty in upscale hotels. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 934–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wei, K.K.; Zhang, J. Understanding customer satisfaction and loyalty: An empirical study of mobile instant messages in China. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2010, 30, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribbink, D.; van Riel, A.C.R.; Liljander, V.; Streukens, S. Comfort your online customer: Quality, trust and loyalty on the internet. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2004, 14, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Advances in International Marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Wang, J.J.; Zhao, P.J.; Chen, K.; Wu, L.B. Factors affecting the willingness of agricultural green production from the perspective of farmers’ perceptions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 140289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M. Multigroup Analysis in Partial Least Squares (PLS) Path Modeling: Alternative Methods and Empirical Results. Advances in International Marketing. In Measurement and Research Methods in International Marketing; Sarstedt, M., Schwaiger, M., Taylor, C.R., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; Volume 22, pp. 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch-Sijtsema, P.M.; Haapamäki, J. Perceived enablers of 3D virtual environments for virtual team learning and innovation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Hjorth, L. Live-streaming, games and politics of gender performance: The case of Nüzhubo in China. Convergence 2019, 25, 807–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.-K.; Choi, H.-J. Broadcasting upon a shooting star: Investigating the success of Afreeca TV’s livestream personal broadcast model. Int. J. Web Based Communities 2017, 13, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.; Ditton, T. At the Heart of It All: The Concept of Presence. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 1997, 3, JCMC321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obst, P.; Zinkiewicz, L.; Smith, S.G. Sense of community in science fiction fandom, Part 2: Comparing neighborhood and interest group sense of community. J. Community Psychol. 2002, 30, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heo, J.; Kim, Y.; Yan, J.Z. Sustainability of Live Video Streamer’s Strategies: Live Streaming Video Platform and Audience’s Social Capital in South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Measure | Category | Total | Group 1 | Group 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Percent | N | Percent | N | Percent | ||

| Gender | Male | 139 | 57.92% | 73 | 60.83% | 66 | 55.00% |

| Female | 101 | 42.08% | 47 | 39.17% | 54 | 45.00% | |

| Age | 18–25 | 77 | 32.08% | 41 | 34.17% | 36 | 30.00% |

| 26–35 | 74 | 30.83% | 35 | 29.17% | 39 | 32.50% | |

| 36–45 | 61 | 25.42% | 33 | 27.50% | 28 | 23.33% | |

| 46–55 | 26 | 10.83% | 9 | 7.50% | 17 | 14.17% | |

| 56–65 | 2 | 0.83% | 2 | 1.67% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Over 65 | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Education | College | 74 | 30.83% | 41 | 34.17% | 33 | 27.50% |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 127 | 52.92% | 56 | 46.67% | 71 | 59.17% | |

| Post Graduate Degree | 39 | 16.25% | 23 | 19.17% | 16 | 13.33% | |

| Viewing Live streaming Frequency (per week) | 1–3 | 10 | 4.17% | 7 | 5.83% | 3 | 2.50% |

| 4–6 | 119 | 49.58% | 55 | 45.83% | 64 | 53.33% | |

| 7–10 | 50 | 20.83% | 31 | 25.83% | 19 | 15.83% | |

| > 10 | 61 | 25.42% | 27 | 22.50% | 34 | 28.33% | |

| Construct | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained Engagement Behaviour (SEB) | 0.952 | 0.965 | 0.874 |

| Social Presence (SPR) | 0.934 | 0.953 | 0.834 |

| Perceived Trust (PTR) | 0.936 | 0.955 | 0.840 |

| Interaction (INT) | 0.893 | 0.926 | 0.759 |

| Emotional Visual Elements (EVE) | 0.968 | 0.972 | 0.921 |

| SEB | SPR | PTR | INT | EVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEB.1 | 0.944 | 0.642 | 0.294 | 0.805 | −0.535 |

| SEB.2 | 0.919 | 0.656 | 0.237 | 0.796 | −0.491 |

| SEB.3 | 0.944 | 0.641 | 0.251 | 0.809 | −0.589 |

| SEB.4 | 0.932 | 0.626 | 0.281 | 0.800 | −0.560 |

| SPR.1 | 0.666 | 0.913 | 0.003 | 0.724 | −0.115 |

| SPR.2 | 0.643 | 0.916 | −0.016 | 0.736 | −0.085 |

| SPR.3 | 0.612 | 0.917 | 0.025 | 0.723 | −0.002 |

| SPR.4 | 0.582 | 0.907 | −0.017 | 0.695 | 0.001 |

| PTR.1 | 0.255 | −0.029 | 0.937 | 0.261 | 0.000 |

| PTR.2 | 0.294 | 0.063 | 0.916 | 0.275 | 0.013 |

| PTR.3 | 0.277 | −0.026 | 0.940 | 0.278 | −0.009 |

| PTR.4 | 0.211 | −0.019 | 0.873 | 0.254 | 0.044 |

| INT.1 | 0.822 | 0.738 | 0.257 | 0.916 | −0.337 |

| INT.2 | 0.743 | 0.662 | 0.282 | 0.855 | −0.281 |

| INT.3 | 0.767 | 0.691 | 0.264 | 0.893 | −0.303 |

| INT.4 | 0.651 | 0.653 | 0.212 | 0.816 | −0.226 |

| EVE.1 | −0.583 | −0.068 | 0.012 | −0.335 | 0.989 |

| EVE.2 | −0.550 | −0.036 | 0.013 | −0.309 | 0.966 |

| EVE.3 | −0.514 | −0.003 | 0.003 | −0.276 | 0.924 |

| SEB | SPR | PTR | INT | EVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEB | 0.935 | ||||

| SPR | 0.686 | 0.913 | |||

| PTR | 0.285 | −0.001 | 0.917 | ||

| INT | 0.859 | 0.788 | 0.292 | 0.871 | |

| EVE | −0.582 | −0.056 | 0.012 | −0.331 | 0.960 |

| Path Relationship | Original Sample | T Statistics | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPR -> SEB | 0.686 | 15.900 | 0.000 |

| PTR -> SEB | 0.286 | 9.795 | 0.000 |

| INT -> SPR | 0.865 | 36.175 | 0.000 |

| INT -> PTR | 0.332 | 4.307 | 0.000 |

| EVE -> SPR | 0.230 | 4.307 | 0.000 |

| EVE -> PTR | 0.122 | 2.786 | 0.005 |

| Path Coefficients-Diff (1–2) | p-Value Original 1-Tailed (1 vs. 2) | p-Value New (1 vs. 2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPR -> SEB | 0.233 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| PTR -> SEB | −0.180 | 0.986 | 0.027 |

| INT -> SPR | −0.028 | 0.618 | 0.764 |

| INT -> PTR | −0.584 | 1.000 | 0.001 |

| EVE -> SPR | 0.474 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| EVE -> PTR | 0.275 | 0.055 | 0.110 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, J.; Cao, C.; Xu, Q.; Ni, L.; Shao, X.; Shi, Y. How Live Streaming Interactions and Their Visual Stimuli Affect Users’ Sustained Engagement Behaviour—A Comparative Experiment Using Live and Virtual Live Streaming. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148907

Lv J, Cao C, Xu Q, Ni L, Shao X, Shi Y. How Live Streaming Interactions and Their Visual Stimuli Affect Users’ Sustained Engagement Behaviour—A Comparative Experiment Using Live and Virtual Live Streaming. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148907

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Jie, Cong Cao, Qianwen Xu, Linyao Ni, Xiuyan Shao, and Yangyan Shi. 2022. "How Live Streaming Interactions and Their Visual Stimuli Affect Users’ Sustained Engagement Behaviour—A Comparative Experiment Using Live and Virtual Live Streaming" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148907

APA StyleLv, J., Cao, C., Xu, Q., Ni, L., Shao, X., & Shi, Y. (2022). How Live Streaming Interactions and Their Visual Stimuli Affect Users’ Sustained Engagement Behaviour—A Comparative Experiment Using Live and Virtual Live Streaming. Sustainability, 14(14), 8907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148907