Sustainability Strategies and Contractual Arrangements in the Italian Pasta Supply Chain: An Analysis under the Neo Institutional Economics Lens

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the main goals that characterize collective sustainability strategies promoted by pasta factories along the Italian pasta supply chain?

- (2)

- Do the variety of collective sustainability goals promoted by pasta factories correspond to contractual terms and incentives that, in turn, differently impact on allocation of property and decision rights?

- (3)

- Do companies with higher level of collective sustainability commitment tend to adopt contractual mechanisms characterized by a higher level of centralization of control over strategic sustainable investment and decision rights?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Literature Review

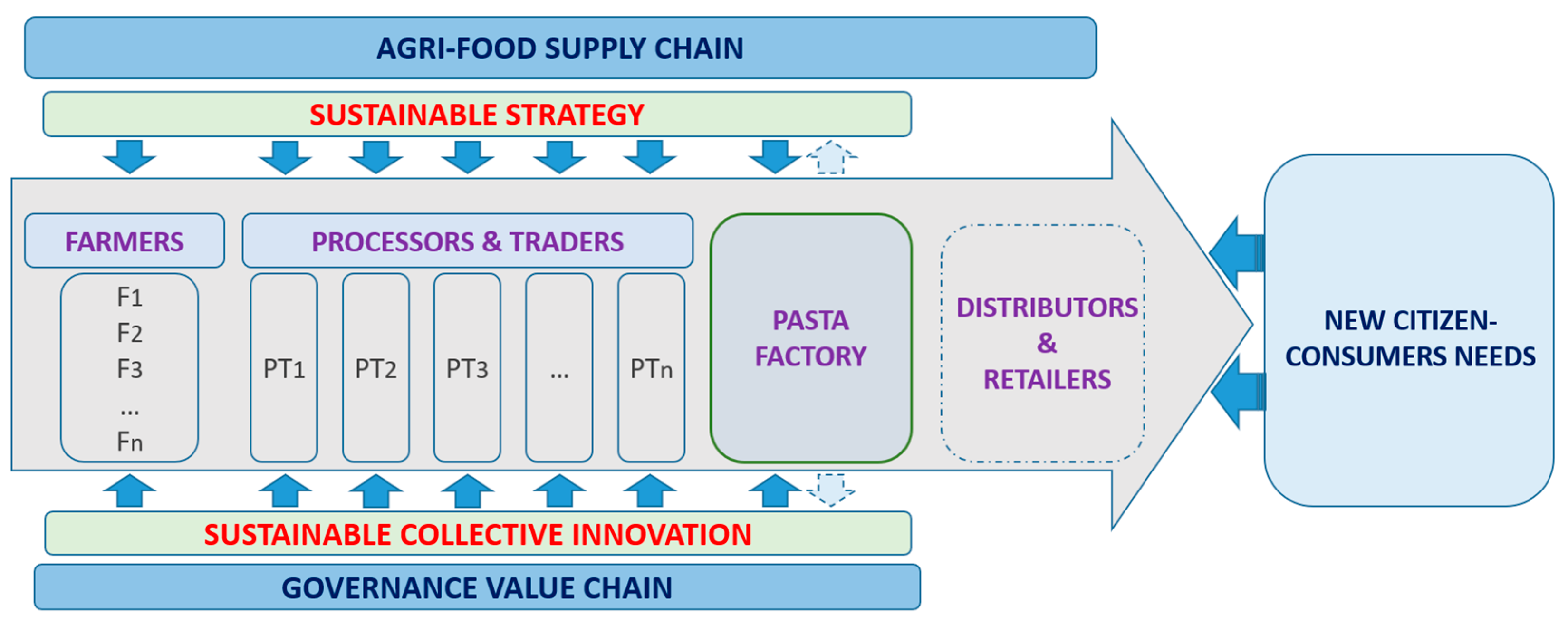

2.2. Conceptual Framework

3. Materials and Methods

- First, we detected which were the characteristics of the sustainability strategies promoted by the Italian pasta factories, in terms of specific objectives pursued based on available documentations (leaflets, company website, and publications) that were scrupulously fact-checked by means of open interviews with stakeholders and key informants. As a result, we identified, specified and associated each case with at least one of the 17 SDGs of the UN;

- As second step, we classified pasta factories according to the width of their sustainability commitments (that is, the number and typology of SDGs to which they intend to contribute) in order to identify literal and theoretical replications of our multiple embedded case study;

- The third step entailed the analysis of the relationships between different level of sustainability commitments and types of contracts used in order to govern transactions between pasta producers and durum wheat producers. Thus, we carefully explored and classified the variety of contractual clauses at stake and their functions related to the type of incentives they provided;

- Lastly, we scrutinized incentives in order to comparatively investigate whether and how different width of sustainability commitments differently impacted the centralization/decentralization of decision and property rights among pasta factories and farmers.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Case Studies and Contracts under Analysis

4.2. Analysis and Classification of Sustainable Strategies of Italian Pasta Factories

4.3. Analysis and Classification of Contractual Attributes and Functions

4.4. Impacts of Collective Sustainable Commitments on Decision and Property Rights

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAOSTAT. 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/ (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Chandio, A.A.; Jiang, Y.; Rehman, A.; Rauf, A. Short and long-run impacts of climate change on agriculture: An empirical evidence from China. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Str. 2020, 12, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, C.; Lerro, M.; Stanco, M.; Marotta, G. Do consumers like food product innovation? An analysis of willingness to pay for innovative food attributes. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 1413–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerro, M.; Vecchio, R.; Nazzaro, C.; Pomarici, E. The growing (good) bubbles: Insights into US consumers of sparkling wine. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2371–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, G.; Nazzaro, C. Public goods production and value creation in wineries: A structural equation modelling. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1705–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System. Communication from the EU Commission, COM. 2020. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/publication/communication-com2020381-farm-fork-strategy-fair-healthy-environmentally-friendly-food_en (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- European Commission. The Future of Food and Farming. Communication from the EU Commission, COM. 2017. Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/en/our-work/opinions-information-reports/opinions/future-food-and-farming-communication (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Cacchiarelli, L.; Sorrentino, A. Pricing strategies in the Italian retail sector: The case of pasta. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frascarelli, A.; Ciliberti, S.; Magalhães de Oliveira, G.; Chiodini, G.; Martino, G. Production Contracts and Food Quality: A Transaction Cost Analysis for the Italian Durum Wheat Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancino, B.; Blasi, E.; Rappoldt, A.; Pascucci, S.; Ruini, L.; Ronchi, C. Partnering for sustainability in agri-food supply chains: The case of Barilla Sustainable Farming in the Po Valley. AFE 2019, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ageron, B.; Gunasekaran, A.; Spalanzani, A. Sustainable supply management: An empirical study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 140, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.; Kunz, N.; Reiner, G. Sustainable global agrifood supply chains: Exploring the barriers. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mangla, S.K.; Luthra, S.; Rich, N.; Kumar, D.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Enablers to implement sustainable initiatives in agri-food supply chains. Inte. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 203, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stanco, M.; Nazzaro, C.; Lerro, M.; Marotta, G. Sustainable Collective Innovation in the Agri-Food Value Chain: The Case of the “Aureo” Wheat Supply Chain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; John, G. Strategic fit in industrial alliances: An empirical test of governance value analysis. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard, C. The economics of hybrid organizations. JITE 2004, 160, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, G. Trust, contracting, and adaptation in agri-food hybrid structures. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2010, 1, 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Principato, L.; Ruini, L.; Guidi, M.; Secondi, L. Adopting the circular economy approach on food loss and waste: The case of Italian pasta production. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 144, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingale, S.; Guarnaccia, P.; Timpanaro, G.; Scuderi, A.; Matarazzo, A.; Bacenetti, J.; Ingrao, C. Environmental life cycle assessment for improved management of agri-food companies: The case of organic whole-grain durum wheat pasta in Sicily. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, A.; Cini, E. Challenges and opportunities in wheat flour, pasta, bread, and bakery product production chains: A systematic review of innovations and improvement strategies to increase sustainability, productivity, and product quality. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Thornton, P.K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Palmer, J.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Pradhan, P.; Barrett, C.B.; Benton, T.G.; Hall, A.; Pikaar, I.; et al. Articulating the effect of food systems innovation on the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e50–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Pearson, P. Final Report MEI Project about Measuring Eco-Innovation; UM Merit: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 10, p. 2. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/env/consumptioninnovation/43960830.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Cuerva, M.C.; Triguero, A.; Córcoles, D. Drivers of green and non-green innovation: Empirical evidence in low-tech SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 68, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triguero, A.; Fernández, S.; Sáez-Martinez, F.J. Inbound open innovative strategies and eco-innovation in the Spanish food and beverage industry. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 15, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabadán, A.; Triguero, Á.; Gonzalez-Moreno, Á. Cooperation as the secret ingredient in the recipe to foster internal technological eco-innovation in the agri-food industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triguero, A.; Córcoles, D. Understanding innovation: An analysis of persistence for Spanish manufacturing firms. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A. Sustainability marketing research: Past, present and future. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 30, 1186–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesidou, E.; Demirel, P. On the drivers of eco-innovations: Empirical evidence from the UK. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frondel, M.; Horbach, J.; Rennings, K. What triggers environmental management and innovation? Empirical evidence for Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 66, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Segarra-Oña, M.D.V.; Peiró-Signes, A.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J. Identifying variables affecting the proactive environmental orientation of firms: An empirical study. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2013, 22, 873–880. [Google Scholar]

- De Marchi, V. Environmental innovation and R&D cooperation: Empirical evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 614–623. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez-Martínez, F.J.; González-Moreno, A.; Díaz-García, C. Environmental orientation as a determinant of innovation performance in young SMEs. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2014, 8, 635–642. [Google Scholar]

- Rabadán, A.; González-Moreno, Á.; Sáez-Martínez, F.J. Improving firms’ performance and sustainability: The case of eco-innovation in the agri-food industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marotta, G.; Nazzaro, C. Responsabilità sociale e creazione di valore nell’impresa agroalimentare: Nuove frontiere di ricerca. Economia agro-alimentare. Franco Angeli Milano 2012, 1, 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Nazzaro, C.; Stanco, M.; Marotta, G. The Life Cycle of Corporate Social Responsibility in Agri-Food: Value Creation Models. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kunzik, P. National Procurement Regimes and the Scope for the Inclusion of Environmental Factors in Public Procurement. In The Environmental Performance of Public Procurement: Issues of Policy Coherence; OECD: Paris, France, 2003; pp. 193–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cholez, C.; Magrini, M.B.; Galliano, D. Exploring inter-firm knowledge through contractual governance: A case study of production contracts for faba-bean procurement in France. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 73, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamuloh, V.; Panwar, R.; Hagerman, S.M.; Gaston, C.; Kozak, R.A. Achieving Sustainable Development Goals in the global food sector: A systematic literature review to examine small farmers engagement in contract farming. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2019, 2, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beber, C.L.; Langer, G.; Meyer, J. Strategic actions for a sustainable internationalization of agri-food supply chains: The case of the dairy industries from Brazil and Germany. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayet, L.; Vermeulen, W.J.V. Supporting smallholders to access sustainable supply chains: Lessons from the Indian cotton supply chain. J. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montefrio, M.J.F.; Sonnenfeld, D.A.; Luzadis, V.A. Social construction of the environment and smallholder farmers’ participation in ‘low-carbon’, agro-industrial crop production contracts in the Philippines. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 116, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formentini, M.; Taticchi, P. Corporate sustainability approaches and governance mechanisms in sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1920–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vazquez-Brust, D.; Piao, R.S.; de Melo, M.F.D.S.; Yaryd, R.T.; Carvalho, M.M. The governance of collaboration for sustainable development: Exploring the “black box”. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberti, S.; Del Sarto, S.; Frascarelli, A.; Pastorelli, G.; Martino, G. Contracts to Govern the Transition towards Sustainable Production: Evidence from a Discrete Choice Analysis in the Durum Wheat Sector in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard, C. Finding our way in the jungle: Insights from organization theory. In It’s a Jungle Out There—The Strange Animals of Economic Organization in Agri-Food Value Chains; Martino, G., Karantininis, K., Pascucci, S., Dries, L.K., Codron, J.M., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 124–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ménard, C. Organization and governance in the agrifood sector: How can we capture their variety? Agribusiness 2018, 34, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism; The Free Press Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Iacoponi, L. Modelli di Adozione Delle Innovazioni e Sistemi Agricoli Locali. In Nuovi modelli di sviluppo dell’agricoltura e innovazione tecnologica; Iacoponi, L., Marotta, G., Eds.; INEA: Roma, Italy, 1995; pp. 63–118. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research Design and Methods, 6th ed.; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Herriott, R.E.; Firestone, W.A. Multisite Qualitative Policy Research: Optimizing Description and Generalizability. Edu. Res. 1983, 12, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iazzi, A.; Ligorio, L.; Vrontis, D.; Trio, O. Sustainable Development Goals and healthy foods: Perspective from the food system. Brit. Food J. 2021, 124, 1081–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peano, C.; Tecco, N.; Dansero, E.; Girgenti, V.; Sottile, F. Evaluating the sustainability in complex agri-food systems: The SAEMETH framework. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6721–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moggi, S.; Bonomi, S.; Ricciardi, F. Against food waste: CSR for the social and environmental impact through a network-based organizational model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naidoo, M.; Gasparatos, A. Corporate environmental sustainability in the retail sector: Drivers, strategies and performance measurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicarelli, V.; Bux, C. Food waste measurement toward a fair, healthy and environmental friendly food system: A critical review. Br. Food J. 2020, 12, 2907–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimbo, F.; Russo, C.; Di Fonzo, A.; Nardone, G. Consumers’ environmental responsibility and their purchase of local food: Evidence from a large-scale survey. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 1853–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranieri, S.; Orsi, L.; Banterle, A.; Ricci, E.C. Sustainable development and supply chain coordination: The impact of corporate social responsibility rules in the European Union foo industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovleva, N.; Vazquez-Brust, D.A. Multinational mining enterprises and artisanal small-scale miners: From confrontation to cooperation. J. World Bus. 2018, 53, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ciliberti, S.; Martino, G.; Frascarelli, A.; Chiodini, G. Contractual arrangements in the Italian durum wheat supply chain: The impacts of the “Fondo grano duro”. Econ. Agro-Aliment. Food Econ. 2019, 21, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricome, A.; Chaïb, K.; Ridier, A.; Képhaliacos, C.; Carpy-Goulard, F. The role of marketing contracts in the adoption of low-input production practices in the presence of income supports: An application in South-western France. J. Agr. Resour. Econ. 2016, 41, 347–371. [Google Scholar]

- Federgruen, A.; Lall, U.; Şimşek, A.S. Supply chain analysis of contract farming. Manuf. Ser. Op. 2019, 21, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhue, R.E. Food quality: The design of incentive contracts. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2011, 3, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsellino, V.; Schimmenti, E.; Bilali, H.E. Agri-Food Markets towards Sustainable Patterns. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Zegher, J.F.; Iancu, D.A.; Lee, H.L. Designing contracts and sourcing channels to create shared value. M&SOM-Manuf. Serv. Op. 2017, 21, 271–289. [Google Scholar]

- Mellewigt, T.; Decker, C.; Eckhard, B. What drives contract design in alliances? Taking stock and how to proceed. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2012, 82, 839–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruben, R.; Zuniga, G. How standards compete: Comparative impact of coffee certification schemes in Northern Nicaragua. Supply Chain Manag. 2011, 16, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, J.D. The political economy of agroecology. J. Peasant Stud. 2021, 48, 274–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Schutter, O. The political economy of food systems reform. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2017, 44, 705–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard, C. Hybrids: Where are we? J. I. Econ. 2022, 18, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, A.; Brouwer, R. Testing participation constraints in contract design for sustainable soil conservation in Ethiopia. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 73, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Single | Multiple | ||

| Unit of analysis | Single (holistic) | Single holistic case study | Multiple holistic case study |

| Multiple (embedded) | Single embedded case study | Multiple embedded case study | |

| Functions and Types of Contractual Attributes | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control over Strategic Assets | Coordination of Production Decisions | Coordination of Decisions on Selling | Safeguard Clauses | ||||||||||||||

| Type of Case Study | Case Study ID | Contract ID | Identification of Cultivated Area—Location and Provenance | (Supply of) Durum Wheat Cultivar | Agricultural Practices (Production Specification) | Technical Assistance | Decision Support System | (Environmental, Social) Certification/Requirements | Quality Requirements | Pesticides Requirements (Acceptability Threshold) | Premium Price for Protein Content | Fixed Price | Modality of Payment | Modality of Delivery | Exclusivity | Non-Disclosure | Visit and Inspections |

| Literal replications | A | A1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| A2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| B | B1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| B2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| B3 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| B4 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| B5 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| C | C1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| C2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| D | D1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| Theoretical replications | E | E1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||

| E2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||

| F | F1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| F2 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

| G | G1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| H | H1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| I | I1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||

| J | J1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||

| K | K1 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciliberti, S.; Stanco, M.; Frascarelli, A.; Marotta, G.; Martino, G.; Nazzaro, C. Sustainability Strategies and Contractual Arrangements in the Italian Pasta Supply Chain: An Analysis under the Neo Institutional Economics Lens. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148542

Ciliberti S, Stanco M, Frascarelli A, Marotta G, Martino G, Nazzaro C. Sustainability Strategies and Contractual Arrangements in the Italian Pasta Supply Chain: An Analysis under the Neo Institutional Economics Lens. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148542

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiliberti, Stefano, Marcello Stanco, Angelo Frascarelli, Giuseppe Marotta, Gaetano Martino, and Concetta Nazzaro. 2022. "Sustainability Strategies and Contractual Arrangements in the Italian Pasta Supply Chain: An Analysis under the Neo Institutional Economics Lens" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148542

APA StyleCiliberti, S., Stanco, M., Frascarelli, A., Marotta, G., Martino, G., & Nazzaro, C. (2022). Sustainability Strategies and Contractual Arrangements in the Italian Pasta Supply Chain: An Analysis under the Neo Institutional Economics Lens. Sustainability, 14(14), 8542. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148542