Exploring Customers’ Experiences with P2P Accommodations: Measurement Scale Development and Validation in the Chinese Market

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Customer Experience

2.2. P2P Accommodations and Experiences

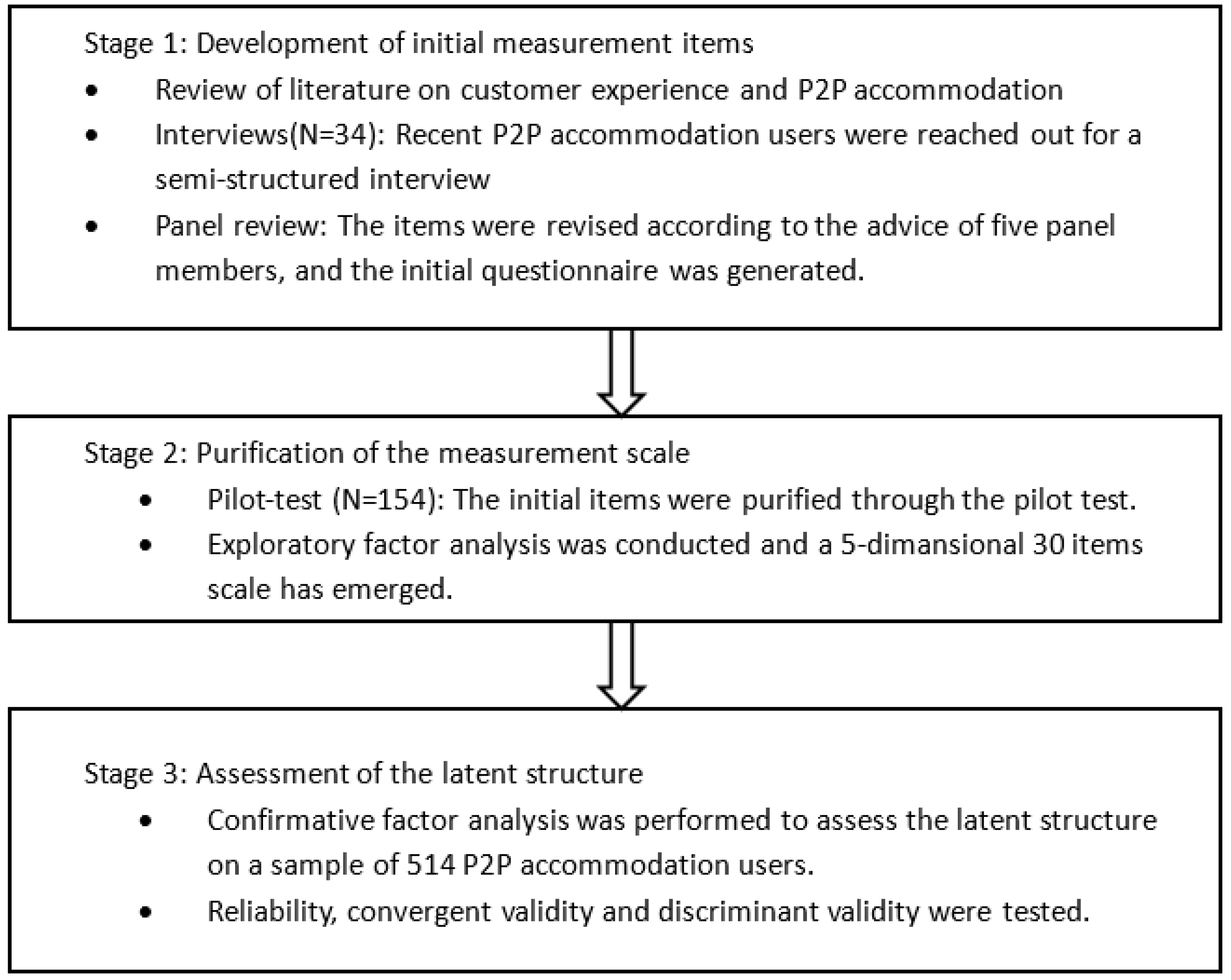

3. Methodology

3.1. Step 1—In-Depth Interviews

3.2. Step 2—Questionnaire Development

3.3. Step 3—Pilot Study

3.4. Step 4—Main Survey

3.4.1. Demographic Profile of Main Survey

3.4.2. Travel- and Accommodation-Related Information

3.4.3. Measurement Model of Customer Experience

3.4.4. Reliability and Validity of Customer Experience Measurement Scale

4. Theoretical Implications

5. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zervas, G.; Proserpio, D.; Byers, J.W. The Rise of the Sharing Economy: Estimating the Impact of Airbnb on the Hotel Industry. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Airbnb. About Us. Available online: https://press.airbnb.com/about-us/ (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Guttentag, D.; Smith, S.; Potwarka, L.; Havitz, M. Why Tourists Choose Airbnb: A Motivation-Based Segmentation Study. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Jin, X. What do Airbnb users care about? An analysis of online review comments. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Mittal, B.; Newman, B.I. Customer Behavior: Consumer Behavior and Beyond; Dryden Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Ma, L.; Jiang, R. A cross-cultural study of English and Chinese online platform reviews: A genre-based view. Discourse Commun. 2019, 13, 342–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China State Information Center. 2018 Chinese Sharing Accommodation Development Report. Available online: http://www.sic.gov.cn/News/568/9241.htm (accessed on 18 May 2018).

- Zhang, G.; Wang, R.; Cheng, M. Peer-to-peer accommodation experience: A Chinese cultural perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, B.J.; Beck, J.A.; Kim, S.; Cha, J. Identifying the Dimensions of the Guest’s Hotel Experience. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2009, 50, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giritlioglu, I.; Jones, E.; Avcikurt, C. Measuring food and beverage service quality in spa hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.; Wang, S.; Tang, C. Understanding the normative expectations of customers toward Buddhism-themed hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1409–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, D.A.; Collins, M.D.; Nale, R.D.; Barr, P.B. Measuring service quality in mid-scale hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Mattila, A.S. Why do we buy luxury experiences?: Measuring value perceptions of luxury hospitality services. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1848–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Qiu, H.; Wang, P.; Lin, P.M.C. Exploring customer experience with budget hotels: Dimensionality and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mody, M.; Suess, C.; Lehto, X. Using segmentation to compete in the age of the sharing economy: Testing a core-periphery framework. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 78, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Rahman, Z. Brand Experience Anatomy in Hotels: An Interpretive Structural Modeling Approach. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2016, 58, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Tang, L.; Bosselman, R. Measuring customer perceptions of restaurant innovativeness: Developing and validating a scale. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S. Measuring tourists’ meal experience by mining online user generated content about restaurants. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 19, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, A.; Pyun, K. Developing a scale measuring customers’ servicescape perceptions in upscale hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 32, 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings, and Fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, C.; Spiller, N.; Noci, G. How to Sustain the Customer Experience. Eur. Manag. J. 2007, 25, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Schwager, A. Understanding customer experience. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashley, C. Studying Hospitality: Insights from Social Sciences1. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2008, 8, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Vajic, M. The Contextual and Dialectical Nature of Experiences; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Carù, A.; Cova, B. Revisiting Consumption Experience: A more humble but complete view of the concept. Mark. Theory 2016, 3, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaSalle, D.; La Salle, D.; Britton, T. Priceless: Turning Ordinary Products into Extraordinary Experiences; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson, B.J.; Beck, J.A.; Kim, S.; Cha, J. Service Quality as a Component of the Hospitality Experience: Proposal of a Conceptual Model and Framework for Research. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2010, 13, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Lemon, K.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Roggeveen, A.; Tsiros, M.; Schlesinger, L.A. Customer Experience Creation: Determinants, Dynamics and Management Strategies. J. Retail. 2009, 85, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential Marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, A.R.; Okumus, F.; Wang, Y.; Kwun, D.J.-W. An epistemological view of consumer experiences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ozanne, L.K. A systematic review of peer-to-peer (P2P) accommodation sharing research from 2010 to 2016: Progress and prospects from the multi-level perspective. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2018, 27, 649–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D. Progress on Airbnb: A literature review. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019, 10, 814–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Zach, F. Identifying salient attributes of peer-to-peer accommodation experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sthapit, E.; Jiménez-Barreto, J. Exploring tourists’ memorable hospitality experiences: An Airbnb perspective. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jeong, M. What makes you choose Airbnb again? An examination of users’ perceptions toward the website and their stay. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Schuckert, M.; Law, R.; Chen, C.-C. Be a “Superhost”: The importance of badge systems for peer-to-peer rental accommodations. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Back, K.-J.; Choi, Y.; Lee, J.-S. Exploring Airbnb service quality attributes and their asymmetric effects on customer satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, D.-Y. The effect of hedonic and utilitarian values on satisfaction and loyalty of Airbnb users. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1332–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D. Airbnb: Disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 1192–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuqair, S.; Pinto, D.C.; Mattila, A.S. Benefits of authenticity: Post-failure loyalty in the sharing economy. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Li, M.; Law, R. Experiencing P2P accommodations: Anecdotes from Chinese customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulauskaite, D.; Powell, R.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.; Morrison, A.M. Living like a local: Authentic tourism experiences and the sharing economy. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 19, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.M.C.; Fan, D.X.F.; Zhang, H.Q.; Lau, C. Spend less and experience more: Understanding tourists’ social contact in the Airbnb context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockyer, T. Business guests’ accommodation selection: The view from both sides. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2002, 14, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Zhang, G. When Western hosts meet Eastern guests: Airbnb hosts’ experience with Chinese outbound tourists. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belarmino, A.; Koh, Y. A critical review of research regarding peer-to-peer accommodations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M. Airbnb Boss Reveals Plans to Crack Asia Market. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-41023684 (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Guttentag, D.A.; Smith, S.L.J. Assessing Airbnb as a disruptive innovation relative to hotels: Substitution and comparative performance expectations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 64, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker, J.-M.; Klein, K.; Wetzels, M. Hierarchical Latent Variable Models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for Using Reflective-Formative Type Models. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J.M. Grounded Theory in Practice; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G., Jr. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getty, J.M.; Thompson, K.N. The Relationship Between Quality, Satisfaction, and Recommending Behavior in Lodging Decisions. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 1995, 2, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner, M.J. Servicescapes: The Impact of Physical Surroundings on Customers and Employees. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemes, M.D.; Gan, C.; Ren, M. Synthesizing the Effects of Service Quality, Value, and Customer Satisfaction on Behavioral Intentions in the Motel Industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2011, 35, 530–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.-J.; Liang, R.-D. Effect of experiential value on customer satisfaction with service encounters in luxury-hotel restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Cheng, M.; Wang, J.; Ma, L.; Jiang, R. The construction of home feeling by Airbnb guests in the sharing economy: A semantics perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Mak, B.; Jones, D. A Model of Customer Satisfaction and Retention for Hotels. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2006, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Park, S. When guests trust hosts for their words: Host description and trust in sharing economy. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Pesonen, J. Drivers and barriers of peer-to-peer accommodation stay—An exploratory study with American and Finnish travellers. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 703–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, A.; Crawford, A. Network hospitality in the share economy. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2444–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Miao, L.; Hanks, L.; Line, N.D. Peer-to-peer interactions: Perspectives of Airbnb guests and hosts. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, A.J.; Siggs, A. An Exploration of the Experiential Nature of Boutique Accommodation. J. Travel Res. 2016, 44, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Vijver, F.; Hambleton, R.K. Translating tests. Eur. Psychol. 1996, 1, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, M.Y.; Foxall, G.R. A Spanish translation of Mehrabian and Russell’s emotionality scales for environmental consumer psychology. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2002, 2, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall International: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Walls, A.R. A cross-sectional examination of hotel consumer experience and relative effects on consumer values. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Gursoy, D.; Chen, L. Conceptualizing home-sharing lodging experience and its impact on destination image perception: A mixed method approach. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cova, B.; Dalli, D.; Zwick, D. Critical perspectives on consumers’ role as ‘producers’: Broadening the debate on value co-creation in marketing processes. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, A. Collectivism and commitment in Chinese people: Romantic attachment in vertical collectivism. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2017, 45, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring Experience Economy Concepts: Tourism Applications. J. Travel Res. 2017, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmuth, D.; Weisler, A. Airbnb and the rent gap: Gentrification through the sharing economy. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2018, 50, 1147–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tan, K.P.-S.; Li, X. Antecedents and consequences of home-sharing stays: Evidence from a nationwide household tourism survey. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhua. Chinese Leaders Underline Rural Vitalization, High-Quality Development. Available online: http://english.www.gov.cn/news/top_news/2018/03/09/content_281476071711268.htm (accessed on 9 March 2018).

- Huang, J.; Hsu, C.H.C. The Impact of Customer-to-Customer Interaction on Cruise Experience and Vacation Satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2009, 49, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Author(s), Year | Research Field | Name of the Scale | Dimensions of the Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knutson et al., 2009 [9] | hotels | guest’s hotel experience | environment, accessibility, driving benefit, incentive |

| Giritlioglu et al., 2014 [10] | Spa hotels | food and beverage service quality | assurance and employee knowledge, healthy and attractive food, empathy, tangibles, responsiveness of service delivery, reliability |

| Hung, 2015 [11] | Buddhism-themed hotels | normative expectations | reflection of Buddhism culture in the hotel environment and among the staff, ties with the Buddhism community, extent of Buddhism in the hotel design, worship/meditation considerations |

| Rauch et al., 2015 [12] | mid-scale hotels | service quality | service product, service delivery, service environment |

| Yang and Mattila, 2016 [13] | luxury hospitality industry | luxury hospitality values | functional value, hedonic value, symbolic value, and financial value |

| Ren et al., 2016 [14] | budget hotel | customer experience | tangible-sensorial experience, staff relational/interactional experience, aesthetic perception, location |

| Mody, Suess, and Lehto, 2019 [15] | hotels and Airbnb | accommodation experiencescape | entertainment, education, escapism, esthetics, serendipity, localness, communitas, personalization |

| Khan and Rahman, 2017 [16] | luxury hotel | hotel brand experience | hotel location, hotel stay and ambience, hotel staff competence, hotel website and social media, guest-to-guest experience |

| Kim et al., 2018 [17] | restaurant | customer perceptions of restaurant innovativeness | menu innovativeness, technology-based service innovativeness, experiential innovativeness, promotional innovativeness |

| Jia, 2019 [18] | restaurant | tourists’ meal experience | feeling, price, food, place, time, service |

| Lockwood and Pyun, 2020 [19] | upscale hotels | customers’ servicescape perceptions | aesthetic quality, functionality, atmosphere, spaciousness, and physiological conditions |

| Dimensions | Sample Quotes |

|---|---|

| 1. Physical environment | |

| Clean, tidy, hygienic |

| Spacious room, suite room, entire house; nice for family stay |

| Well-furnished, kitchen, washing machine, speedy WIFI, recreational facilities |

| “The washing supplies were good-quality branded products” |

| “The room key used a password, which made me feel safe” |

| Stylish and unique; exquisite design |

| “The room design was the same as shown online”; “The room was not as spacious as shown online” |

| 2. Location | |

| Located in a central area; close to train station/attractions; convenient transportation and access |

| Natural and quiet surroundings |

| Supermarket or local market nearby; local food restaurants |

| 3. Sensory perceptions | |

| Feel at home; warm, homelike feelings |

| Atmosphere with literature and art; full of artistic ambiance |

| “Soft lighting makes me feel cozy and relaxed” |

| “The room is equipped with an aroma diffuser, and it was turned on before we arrived” |

| 4. Service quality | |

| “There was no service staff to clean the room for us, and we needed to take the garbage out ourselves” |

| Pick-up service is provided |

| “The service staff were very friendly and polite; they smiled and greeted us whenever encountered” |

| Service staff are conscientious and responsive |

| 5. Guest–host relations | |

| “Our flight was delayed, and the host waited for us until midnight”; “We booked the room online successfully, but the host said no room was available when we arrived” |

| “The host didn’t appear”; “The host lived upstairs and greeted us every day” |

| Warmly welcomed by the host; “The host prepared lemon pie for us as a welcome dessert” |

| The host gives travel advice and recommends restaurants; the host helps us book tickets |

| “We chatted with the host and shared personal stories”; “The host took us to the local market” |

| The host cares about the guests; the host takes care of guests like family |

| 6. Interaction with peer guests | |

| Review other guests’ comments; ask for other guests’ advice |

| Enjoy a barbecue; cook meals together; outdoor activities |

| Chat and share travel experiences; share personal stories and make friends |

| 7. Local cultural experiences | |

| The host cooks local food for the guests |

| Live with local people; the host speaks the local dialect |

| The room contains local cultural elements |

| Items Derived from the Literature and/or Interviews | Literature (Examples) | Interview | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The exterior of the property is visually appealing. | Bitner (1992) [55], Clemes et al. (2011) [56] | √ |

| 2 | The design of the room is visually appealing. | Wu and Liang (2009) [57]; Clemes et al. (2011) [56]; Zhu et al. (2019a) [58] | √ |

| 3 | The room is clean and sanitary. | Wu and Liang (2009) [57] | √ |

| 4 | The room is spacious. | Lyu et al. (2019) [42]; Guttentag et al. (2018) [3] | √ |

| 5 | The layout of the room feels good. | Bitner (1992) [55] | √ |

| 6 | The room facilities (e.g., TV and air-conditioning) are in good condition. | Clemes et al. (2011) [56]; Lyu et al. (2019) [42]; Zhu et al. (2019a) [58] | √ |

| 7 | The room is quiet. | Bitner (1992) [55]; Clemes et al. (2011) [56] | √ |

| 8 | The use of the free WIFI is smooth. | Ren et al. (2016) [14] | √ |

| 9 | The area surrounding the property is good. | Knutson et al. (2009) [9]; Zhu et al. (2019a) [58] | √ |

| 10 | The location is convenient. | Tussyadiah and Zach (2017) [34];Guttentag et al. (2018) [3] | √ |

| 11 | There are multiple choices for living facilities nearby. | Zhu et al. (2019a) [58] | √ |

| 12 | The lighting makes me feel comfortable. | Wu and Liang (2009) [57]; Clemes et al. (2011) [56] | √ |

| 13 | The room smells good. | Bitner (1992) [55] | √ |

| 14 | I feel relaxed staying at the property. | Lyu et al. (2019) [42]; Sim et al. (2006) [59] | √ |

| 15 | I feel cozy staying at the property. | Tussyadiah and Zach (2017) [34]; Guttentag et al. (2018) [3] | √ |

| 16 | I feel safe staying at the property. | Lyu et al. (2019) [42]; Guttentag and Smith (2017) [49]; Tussyadiah and Park (2018) [60] | √ |

| 17 | It is smooth to make a reservation through Airbnb. | Guttentag and Smith (2017) [49] | √ |

| 18 | The room is the same as shown online. | Tussyadiah and Park (2018) [60] | √ |

| 19 | I feel comfortable making a reservation on Airbnb. | Guttentag and Smith (2017) [49]; Tussyadiah and Pesonen (2018) [61]; Tussyadiah and Park (2018) [60] | √ |

| 20 | The host contacts me on his/her own. | - | √ |

| 21 | The host can provide information I need. | Tussyadiah and Zach (2017) [34]; Wiles and Crawford (2017) [62] | √ |

| 22 | My check-in process is smooth. | Guttentag and Smith (2017); Zhu et al. (2019a) [58] | √ |

| 23 | The food offered by the host tastes good. | Wiles and Crawford (2017); Zhu et al. (2019a) [58] | √ |

| 24 | The service provided by the host caters to my needs. | Tussyadiah and Zach (2016) [34] | √ |

| 25 | The host is present during my stay. | Lyu et al. (2019) [42]; Moon et al. (2019) [63] | √ |

| 26 | The host is hospitable. | Tussyadiah and Zach (2016) [34] | √ |

| 27 | The host is eager to help. | Tussyadiah and Zach (2016) [34] | √ |

| 28 | I enjoy communicating with the host. | Moon et al. (2019) [63] | √ |

| 29 | The host genuinely cares about me. | Tussyadiah and Zach (2017) [34]; Moon et al. (2019) [63] | √ |

| 30 | Reviews of the property posted on Airbnb are useful. | Liang et al. (2017) [37] | √ |

| 31 | I interact with other guests at this property. | Lin et al. (2019) [44] | √ |

| 32 | I share information with other guests. | Lin et al. (2019) [44] | √ |

| 33 | I enjoy interacting with other guests. | Wu and Liang (2009) [57]; Lin et al. (2019) [44] | √ |

| 34 | The room design contains local cultural elements. | McIntosh and Siggs (2005) [64] | √ |

| 35 | I feel involved in the local community when staying at this property. | Tussyadiah and Pesonen (2016) [61] | √ |

| 36 | The food provided by the host enables me to learn more about local cuisine. | Tussyadiah and Pesonen (2016) [61]; Guttentag et al. (2018) [3] | √ |

| 37 | Living with the local people helps me experience local culture and customs. | Tussyadiah and Pesonen (2016) [61]; Guttentag et al. (2018) [3] | √ |

| Dimensions and Items | Cronbach’s Alpha | Communalities | Factor Loading | Item-to-Total Correlation | Eigenvalue | Variance Explained % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Tangible—Sensory experience | 0.963 | 15.360 | 51.199 | |||

| Exterior design | 0.667 | 0.671 | 0.750 | |||

| Interior design | 0.839 | 0.865 | 0.763 | |||

| Cleanliness | 0.760 | 0.803 | 0.750 | |||

| Spaciousness | 0.602 | 0.669 | 0.704 | |||

| Layout | 0.793 | 0.793 | 0.796 | |||

| Facilities | 0.697 | 0.743 | 0.751 | |||

| Quietness | 0.563 | 0.600 | 0.673 | |||

| WIFI | 0.567 | 0.591 | 0.635 | |||

| Lighting | 0.760 | 0.721 | 0.759 | |||

| Smell | 0.718 | 0.751 | 0.757 | |||

| Relaxing feeling | 0.801 | 0.753 | 0.784 | |||

| Cozy feeling | 0.762 | 0.754 | 0.771 | |||

| 2 Host | 0.946 | 3.340 | 11.133 | |||

| Contacts guest on his/her own | 0.564 | 0.607 | 0.646 | |||

| Information provision | 0.660 | 0.589 | 0.731 | |||

| Check-in service | 0.590 | 0.511 | 0.726 | |||

| Presence during stay | 0.684 | 0.777 | 0.542 | |||

| Hospitality | 0.889 | 0.885 | 0.648 | |||

| Eager to help | 0.934 | 0.917 | 0.680 | |||

| Enjoyable communication | 0.913 | 0.888 | 0.718 | |||

| Cares about guest | 0.792 | 0.805 | 0.668 | |||

| 3 Cultural experience | 0.948 | 2.575 | 8.583 | |||

| Cultural elements | 0.730 | 0.600 | 0.770 | |||

| Feel involved in local community | 0.863 | 0.744 | 0.775 | |||

| Learn more about local food | 0.811 | 0.731 | 0.719 | |||

| Learn more about local culture | 0.881 | 0.776 | 0.759 | |||

| 4 Interaction with peer guests | 0.962 | 1.360 | 4.532 | |||

| Interact with peer guests | 0.921 | 0.899 | 0.530 | |||

| Share information | 0.885 | 0.886 | 0.501 | |||

| Enjoy interactions | 0.868 | 0.869 | 0.520 | |||

| 5 Location | 0.898 | 1.218 | 4.060 | |||

| Good surrounding environment | 0.714 | 0.636 | 0.615 | |||

| Convenient location | 0.837 | 0.834 | 0.515 | |||

| Living facilities | 0.769 | 0.800 | 0.533 |

| Residence Area | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 55 | 10.60% |

| Shanghai | 150 | 28.90% |

| Guangzhou | 175 | 33.70% |

| Shenzhen | 139 | 26.80% |

| Total | 519 | 100% |

| Demographic Variables | Description | No. | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 249 | 48.0 |

| Female | 270 | 52.0 | |

| Age | 18–22 | 59 | 11.4 |

| 23–27 | 149 | 28.7 | |

| 28–32 | 120 | 23.1 | |

| 33–37 | 110 | 21.2 | |

| 38–42 | 45 | 8.7 | |

| 43–47 | 24 | 4.6 | |

| >47 | 12 | 2.3 | |

| Marital status | Married | 212 | 40.8 |

| Single | 296 | 57.0 | |

| Other | 11 | 2.1 | |

| Occupation | College student | 33 | 6.4 |

| Manufacturing worker | 16 | 3.1 | |

| Sales | 49 | 9.4 | |

| Marketing/PR | 23 | 4.4 | |

| Service staff | 17 | 3.3 | |

| Administrator | 42 | 8.1 | |

| HR staff | 24 | 4.6 | |

| Finance staff | 45 | 8.7 | |

| Office clerk | 29 | 5.6 | |

| Technician | 64 | 12.3 | |

| Company managerial staff | 55 | 10.6 | |

| Teacher | 24 | 4.6 | |

| Consultant | 6 | 1.2 | |

| Professionals | 23 | 4.4 | |

| Other | 69 | 13.3 | |

| Education | Middle school or below | 25 | 4.8 |

| High school | 39 | 7.5 | |

| Vocational school | 26 | 5.0 | |

| High school diploma | 119 | 22.9 | |

| Undergraduate | 262 | 50.5 | |

| Postgraduate or above | 48 | 9.2 | |

| Annual income (RMB) | No income | 32 | 6.2 |

| <30,001 | 56 | 10.8 | |

| 30,001–60,000 | 119 | 22.9 | |

| 60,001–90,000 | 81 | 15.6 | |

| 90,001–120,000 | 92 | 17.7 | |

| 120,001–150,000 | 66 | 12.7 | |

| 150,001–180,000 | 26 | 5.0 | |

| >180,000 | 47 | 9.1 |

| Items | Descriptions | No. | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Travel purpose | Business | 64 | 12.3 |

| Tourism | 283 | 54.5 | |

| Family leisure | 146 | 28.1 | |

| Other | 26 | 5 | |

| Length of stay | 1–2 nights | 322 | 62 |

| 3–4 nights | 136 | 26.2 | |

| 5–6 nights | 46 | 8.9 | |

| 7–8 nights | 11 | 2.1 | |

| >8 nights | 4 | 0.8 | |

| Room rate (RMB) | <101 | 34 | 6.6 |

| 101–200 | 143 | 27.6 | |

| 201–300 | 123 | 23.7 | |

| 301–400 | 90 | 17.3 | |

| 401–500 | 68 | 13.1 | |

| 501–600 | 26 | 5 | |

| 601–700 | 9 | 1.7 | |

| >700 | 26 | 5 |

| Indices | Good | Acceptable |

|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | <3.0 | <5.0 |

| GFI | >0.95 | >0.90 |

| CFI | >0.95 | >0.90 |

| TLI | >0.95 | >0.90 |

| RMSEA | <0.05 | <0.08 |

| Measurement Model for CE | Item Statement | T-Value | Std FL | CR | AVE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangible and sensorial experience | 0.96 | 0.69 | |||||

| CE1 | <--- | Tang | Exterior design | N/A | 0.783 | ||

| CE2 | <--- | Tang | Interior design | 12.734 | 0.884 | ||

| CE3 | <--- | Tang | Cleanliness | 11.92 | 0.842 | ||

| CE4 | <--- | Tang | Spaciousness | 10.679 | 0.775 | ||

| CE5 | <--- | Tang | Layout | 12.662 | 0.88 | ||

| CE6 | <--- | Tang | Facilities | 11.579 | 0.824 | ||

| CE7 | <--- | Tang | Quietness | 9.665 | 0.715 | ||

| CE8 | <--- | Tang | WIFI | 9.608 | 0.712 | ||

| CE12 | <--- | Tang | Lighting | 12.203 | 0.857 | ||

| CE13 | <--- | Tang | Smell | 12.172 | 0.855 | ||

| CE14 | <--- | Tang | Relaxing feeling | 12.713 | 0.883 | ||

| CE15 | <--- | Tang | Cozy feeling | 12.511 | 0.873 | ||

| Host | 0.92 | 0.59 | |||||

| CE16 | <--- | Host | Contacts guest on his/her own | N/A | 0.748 | ||

| CE17 | <--- | Host | Information provision | 10.924 | 0.843 | ||

| CE18 | <--- | Host | Check-in service | 11.081 | 0.854 | ||

| CE19 | <--- | Host | Presence during stay | 10.71 | 0.829 | ||

| CE20 | <--- | Host | Hospitality | 8.128 | 0.648 | ||

| CE21 | <--- | Host | Eager to help | 9.856 | 0.771 | ||

| CE22 | <--- | Host | Enjoyable communication | 9.912 | 0.775 | ||

| CE23 | <--- | Host | Cares about guest | 8.723 | 0.691 | ||

| Cultural experience | |||||||

| CE27 | <--- | Cult | Cultural elements | N/A | 0.976 | 0.93 | 0.77 |

| CE28 | <--- | Cult | Feel involved in local community | 40.006 | 0.98 | ||

| CE29 | <--- | Cult | Learn more about local food | 20.831 | 0.879 | ||

| CE30 | <--- | Cult | Learn more about local culture | 9.65 | 0.624 | ||

| Interaction with peer guests | 0.85 | 0.66 | |||||

| CE24 | <--- | Inte | Interact with peer guests | N/A | 0.491 | ||

| CE25 | <--- | Inte | Share information | 6.645 | 0.863 | ||

| CE26 | <--- | Inte | Enjoy interactions | 6.952 | 1.003 | ||

| Location | 0.9 | 0.76 | |||||

| CE9 | <--- | Loca | Good surrounding environment | N/A | 0.777 | ||

| CE10 | <--- | Loca | Convenient location | 12.62 | 0.929 | ||

| CE11 | <--- | Loca | Living facilities | 12.324 | 0.901 | ||

| Indicator | χ2 | df | χ2/df | GFI | TLI | CFI | IFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 1623.957 | 395 | 4.111 | 0.818 | 0.891 | 0.901 | 0.902 | 0.078 |

| Customer Experience | Tang | Host | Cult | Inte | Loca | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer experience | 1 | |||||

| Tang | 0.949 ** | 1 | ||||

| Host | 0.923 ** | 0.801 ** | 1 | |||

| Cult | 0.872 ** | 0.758 ** | 0.787 ** | 1 | ||

| Inte | 0.823 ** | 0.710 ** | 0.736 ** | 0.760 ** | 1 | |

| Loca | 0.833 ** | 0.786 ** | 0.716 ** | 0.660 ** | 0.621 ** | 1 |

| AVE | 0.69 | 0.59 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.76 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lyu, J.; Fang, S. Exploring Customers’ Experiences with P2P Accommodations: Measurement Scale Development and Validation in the Chinese Market. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148541

Lyu J, Fang S. Exploring Customers’ Experiences with P2P Accommodations: Measurement Scale Development and Validation in the Chinese Market. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148541

Chicago/Turabian StyleLyu, Jing, and Sha Fang. 2022. "Exploring Customers’ Experiences with P2P Accommodations: Measurement Scale Development and Validation in the Chinese Market" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148541

APA StyleLyu, J., & Fang, S. (2022). Exploring Customers’ Experiences with P2P Accommodations: Measurement Scale Development and Validation in the Chinese Market. Sustainability, 14(14), 8541. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148541