The Economies of Identities: Recognising the Economic Value of the Characteristics of Territories

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Review

3. Methodological Approach

4. Results

4.1. Exploring the Economies of Identities

Conceptualizing the Identities of Territories

- They are discursively constructed through the selection of certain characteristics of a specific area. In each moment, territorial agents select those characteristics that are compatible with their interests and ignore others [74]. Those characteristics that are used to represent a territory are usually called identity markers [75];

- Identities are constantly changing, and they are cumulative [76]. They combine different elements, and although history and the past are considered valuable resources for representing a territory, elements associated with the present and their perceived future are also part of the identity discourses [77];

- They reflect the existing power geometries, as the prevailing identity narratives are those defined by those groups which have more power. In this sense, they are contested, contradictory and multiple [78];

- As identities are modelled by events and political strategies and are instrumentalized for different purposes, they must be analysed considering their social, economic, and political contexts.

4.2. Illustrative Case Studies

4.2.1. The Way of Saint James

- Strategies: In 1985 the historical centre of Santiago de Compostela was designated as World Heritage Site by UNESCO; in 1987 the French route of the Way of Saint James was declared the first European Cultural Route and in 1993 integrated the World Heritage Site list by UNESCO. In parallel the Galician Regional Government created a brand called “Xacabeo” through which powerful promotional campaigns based on cultural programmes aimed at leveraging the Way in the Holy Years (whenever the patron saint’s day (25 July) falls on a Sunday) were carried out [104]. Relevant investments and efforts were channelled to monuments and cultural facilities along the route to improve its heritage value and to raise the attraction capacity of this touristic product, as it is described in Lois González et al. [102]. Together with the applied certification schemes and the recovery investments done, campaigns promoting the city of Santiago and its pilgrimage routes were run, inside and outside borders, through social media channels, cinema, textbooks, advertising, exhibitions and conferences. All these initiatives contributed to position the Way as the main European pilgrimage route [105].

- Narratives: To the construction of the Camino as a touristic destination identity-based narratives composed by tangible and intangible assets deeply rooted in the places through which it passes through were essential. The analysed texts revealed that the Camino is presented as being deeply associated with the cultural values of its territories, as having an ancient origin and as being authentic. As might be expected, references to pilgrimage and to the apostle are transversal to narratives from different sources. Its importance as place of cultural exchange between the Iberian Peninsula and the rest of Europe is also referred in the studied narratives. The following sentences taken from the first paragraphs of the studied texts are representative of the existent alignment among narratives from different stakeholders:

“The Route of Santiago de Compostela is an extensive interconnected network of pilgrimage routes in Spain whose ultimate destination is the tomb of the Apostle James the Greater in Santiago de Compostela, in Galicia.”UNESCO

“The Camino de Santiago (Way of St James) originated as a medieval pilgrimage and ever since people have taken up the challenge of the Camino and walked to Santiago de Compostela.”Lonely Planet (p. 154)

“The Camino de Santiago or Way of Saint James, is the Europe’s oldest pilgrimage route and also the most travelled. We propose seven different and unique experiences along the seven historic itineraries that make up The Way.”Turgalicia

“Since the Middle Ages, people of all origins and conditions have often walked towards Santiago de Compostela along the Jacobean routes. They advance bringing us their culture, their language and their idiosyncrasy. Leaving us, therefore, his mark, but also receiving something from us.”Xacobeo Strategic Plan

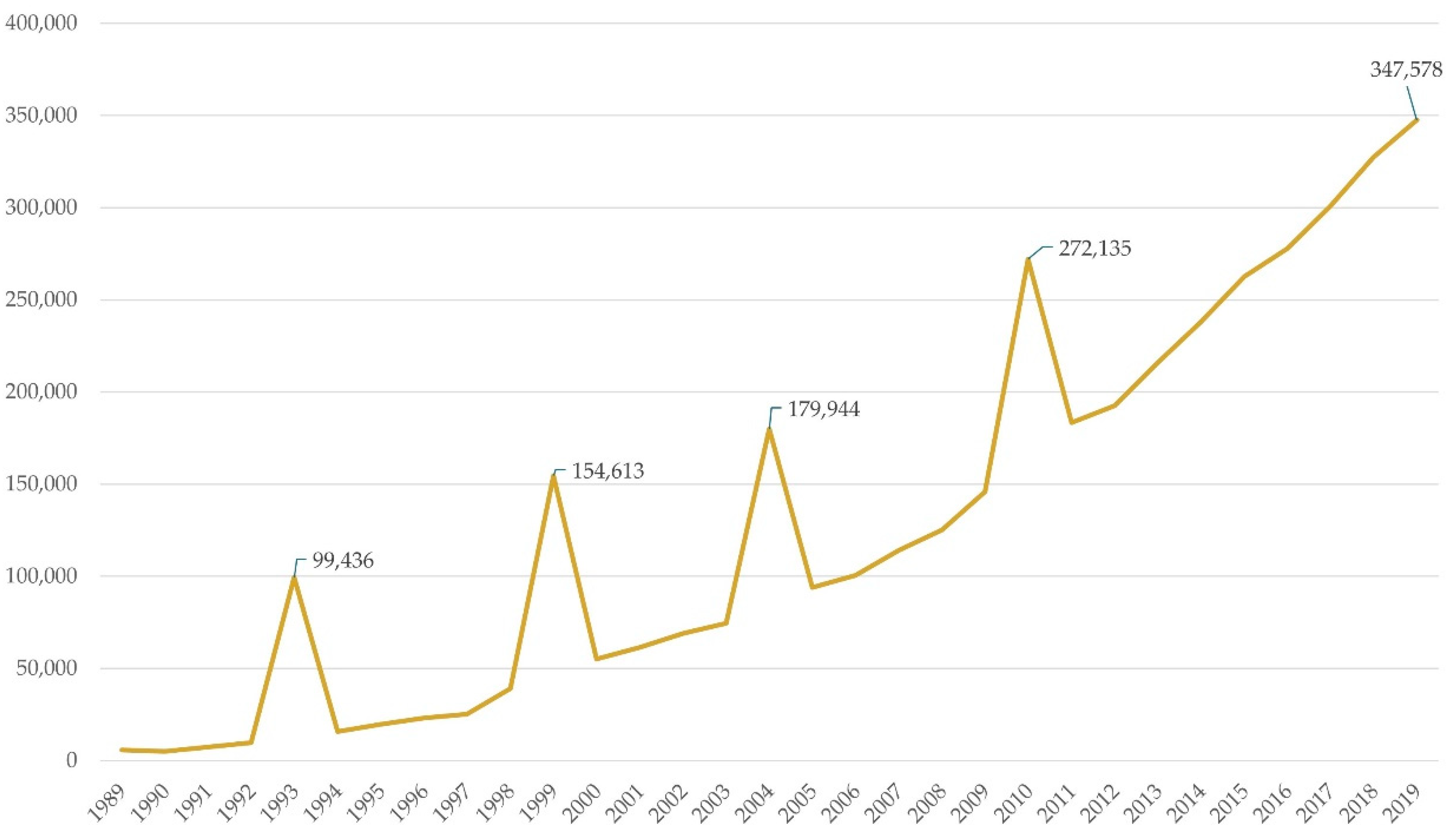

- Outcomes: The success of this route can be verified in the temporal evolution of the number of pilgrims arriving in Santiago. In 1989 there were 5760 requirements of compostelanas (Document which certifies the completion of the pilgrimage), in 1999 these number raised to 154,613 and in 2009 there were 145,877 registered requests, as it is showed in Figure 1. This figure reveal two phenomena. On the one hand, a continued steady increase in the number of pilgrims arriving to Santiago and, on the other hand, peaks of increase in certain years which correspond to the Compostela Holy Years. In 2019 the number of pilgrims arriving to Santiago de Compostela reached the 347,578 people (Pilgrim’s Office). Considering the data collected, in 2019 there were registrations of people from almost every country in the world, with Italy, German, United States, Portugal, France and United Kingdom being the most representative origins after Spain. In 2019 the French way, the one which links Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port in France, to Santiago de Compostela, was still the most important route, as it was chosen by 54,65% of the pilgrims, followed by the Portuguese inner-way, the one chosen by 20,82% of people arriving at Santiago. A recent study [106] revealed that each pilgrim bears the same economic impact as 2.3 domestic visitors and each euro spent by a pilgrim generates up to 18% of additional employment. This can be explained by the differences in the average stay, average expenditure, and the multiplier effect.

4.2.2. Douro Valley

- Strategies: Douro has currently different types of certifications schemes for its territory and products. Douro’s terroir (term used to refer to the unique configurations of environmental conditions in a vineyard (microclimate, topography and soil) considered fundamental to the taste and character of the product [95]) is the basis for the existence of two designations of origin of wine: Port Wine and Douro. The characteristics that guarantee the authenticity of this landscape and are recognised by the UNESCO are also protected by the Portuguese law, under a special protection zone (Zona Especial de Protecção (ZEP)) designation. Moreover, this area is integrated in the Douro International Natural Park, an area of about 860 km2, along the banks of the river, a cross-border natural protected area between Portugal and Spain. The singularity of Douro’s territory relies on the fact that it is considered an example of integration between the human activity and nature, and it testifies the joint development of geographical and historical factors [111].

- Narratives: The analysed narratives about Douro show a strong convergence in the discourses about this territory: elements such as wine, landscape and the river are present in all the analysed territorial descriptions. We have identified that independently from the nature of the narratives, from territorial planning documents to travel guides or to heritage certification documentation, the association of the Douro Valley with these elements is constant, as it can be verified in the following quotes taken from the first paragraphs of each source:

“Wine has been produced by traditional landholders in the Alto Douro region for some 2000 years. Since the 18th century, its main product, port wine, has been world famous for its quality. This long tradition of viticulture has produced a cultural landscape of outstanding beauty that reflects its technological, social and economic evolution.”UNESCO

“This UNESCO World Heritage region is hands down one of Portugal’s most evocative landscapes, with mile after swoon-worthy mile of vineyards spooling along the contours of its namesake river and marching up terraced hillsides. Go for the food, the fabulous wines, the palatial quintas, the medieval stone villages and the postcard views on almost every corner.”Lonely Planet (p. 513)

“Departing from Porto, where the river flows into the sea and where the Douro wines (table wines and Port wine), produced on its hillsides, also end up, there are various ways to get to know this cultural landscape, listed as a World Heritage Site: by road, by train, on a cruise boat and even by helicopter.”Turismo de Portugal

“The Alto Douro Vinhateiro, where a wine has been produced since the 18th century, the port wine, generating an high creation of wealth, has promoted the development of a cultural landscape of enormous natural beauty and which reflects many social, economic and technological developments”ITDS Douro

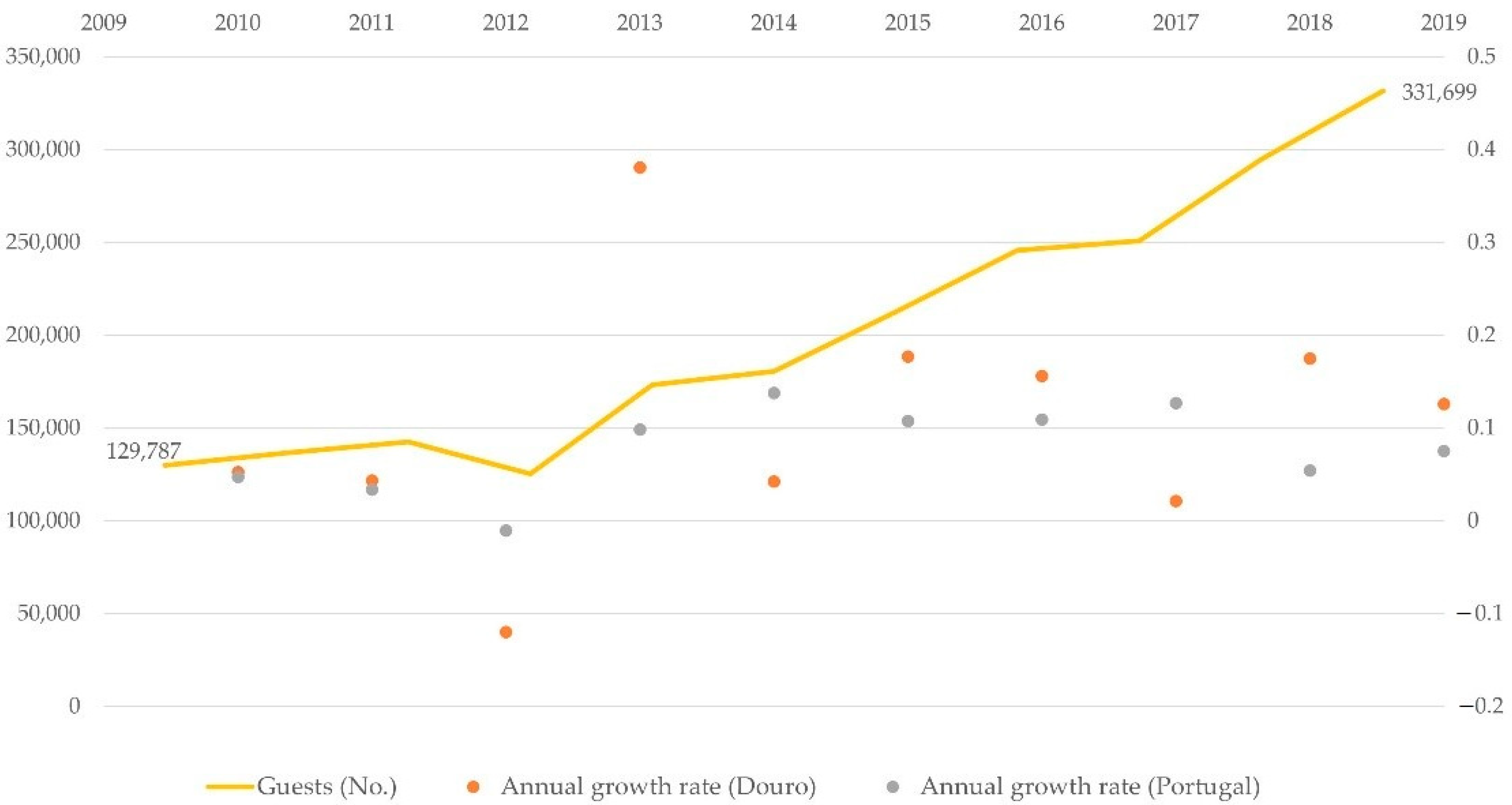

- Outcomes: Facing serious socioeconomic problems such as depopulation and ageing [92], this territory has put its distinct territorial resources at the service of regional development. Keeping wine culture in the centre of the action, new economic functions and usages have been created around this phenomenon, revealing the multiple nature of the economic values of the identities. The efforts done to protected and promote this territory have positioned Douro both as a wine region and a tourist destination. The Douro valley is considered an outstanding example of a traditional European wine-producing region [89] and is currently one of the most important wine regions in Portugal, being responsible for about 1/3 of the total Portuguese wine exports [112]. The results of the development of Douro as a wine producing region are showed in Table 1. Although between 2007 and 2019 variations in the volume of wine production and its sales in euros were registered, the average price per litre of the wine increased 27% in this period. According to the same source, between 2011 and 2019 the number of official wine producers in Douro increased from 785 to 1121.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.; Thrift, N. Cultural-Economy and Cities. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2007, 31, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anholt, S. Competitive Identity—The New Brand Management for Nations, Cities and Regions; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 9780230500280. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.J. The Cultural Economy of Cities. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1997, 21, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capello, R. Interpreting and Understanding Territorial Identity. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2019, 11, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Regional Planning and the Mobilization of ‘Regional Identity’: From Bounded Spaces to Relational Complexity. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1206–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnychuk, A.; Gnatiuk, O. Regional Identity and the Renewal of Spatial Administrative Structures: The Case of Podolia, Ukraine. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2018, 26, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholte, J.A. Globalization. A Critical Introduction; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 9780333977026. [Google Scholar]

- Bisley, N. Rethinking Globalization; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, D. Territory; Harlow; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, D. Territory. A Short Introduction; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2005; ISBN 9781405118316. [Google Scholar]

- Paasi, A. Territory. In A Companion to Political Geography; Agnew, J.A., Mitchell, K., Toal, G., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Painter, J. Rethinking Territory. Antipode 2010, 42, 1090–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonsich, M. Territory and Territoriality. In The International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment, and Technology; Richardson, D., Castree, N., Goodchild, M.F., Kobayashi, A., Liu, W., Marston., R.A., Hoboken, N.W., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 196–208. ISBN 9780080449104. [Google Scholar]

- Raffestin, C.; Butler, S.A. Space, Territory, and Territoriality. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2012, 30, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Examining the Persistence of Bounded Spaces: Remarks on Regions, Territories, and the Practices of Bordering. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2022, 104, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, D. Territory and Territoriality. In Handbook on the Geographies of Regions and Territories; Paasi, A., Harrison, J., Jones, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Billig, M. Banal Nationalism; Sage: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Vainikka, J. Revendications Narratives sur des Régions: Chercher des Identités Spatiales Parmi Les Mouvements Populaires en Finlande. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2012, 13, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlouw, K. Transforming Identity Discourses to Promote Local Interests during Municipal Amalgamations. GeoJournal 2018, 83, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barel, Y. Le Social et Ses Territoires. In Espaces, Jeux et Enjeux; Auriac, F., Brunet, R., Eds.; Fayard-Diderot: Paris, France, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ohmae, K. The Borderless World: Power and Strategy in the Interlinked Economy; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggie, J.G. Territoriality and Beyond: Problematizing Modernity in International Relations. Int. Organ. 1993, 47, 139–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badie, B. La Fin des Territoires. Essai sur le Désordre International et sur L’utilité Sociale du Respect; Fayard: Paris, France, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelesness; Pion Limited: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, T. The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 1981; ISBN 0415255341. [Google Scholar]

- Vertova, G. The Changing Economic Geography of Globalization; Vertova, G., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; Volume 49, ISBN 9780415353984. [Google Scholar]

- Flew, T. Globalization, Neo-Globalization, and Post-Globalization: The Challenge of Populism and the Return of the National. Glob. Media Commun. 2020, 16, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; Rodriguez-Pose, A.; Tomaney, J. Local and Regional Development; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 2006005421. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N. Beyond State-Centrism? Space, Territoriality, and Geographical Scale in Globalization Studies. Theory Soc. 1999, 28, 39–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birstow, G. Critical Reflections on Regional Competitiveness; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 9780415471596. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinelli, C. Competition, Cooperation and Co-Opetition: Unfolding the Process of Inter-Territorial Branding. Urban Res. Pract. 2013, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J. Economic Geography: The Great Half-Cetury. Camb. J. Econ. 2000, 24, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morretta, V. Territorial Capital in Local Economic Endogenous Development. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2021, 13, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Thrift, N. Living in the Global. In Globalisation, Institutions and Regional Development in Europe; Amin, A., Thrift, N., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E. Neither Global nor Local: “Glocalization” and the Politics of Scale. In Spaces of Globalization; Cox, K.R., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 137–166. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, A. Modernity al Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization; Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Radil, S.M.; Castan Pinos, J.; Ptak, T. Borders Resurgent: Towards a Post-Covid-19 Global Border Regime? Space Polity 2021, 25, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J. The Constitution of the City Economy, Society, and Urbanization in the Capitalist Era; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 9783319612270. [Google Scholar]

- Roca, Z.; Oliveira-Roca, M.N. Affirmation of Territorial Identity: A Development Policy Issue. Land Use Policy 2007, 24, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. Geographical Perspectives on Finnish Nationalidentity. GeoJournal 1997, 43, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. The Institutionalization of Regions: A Theoretical Framework for Understanding the Emergence of Regions and the Constitution of Regional Identity. Fennia 1986, 164, 105–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Wang, H. Traditional Literature Review and Research Synthesis. In The Palgrave Handbook of Applied Linguistics Research Methodology; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2018; pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, J.; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the Experience Economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.K.; Lee, W. Country-of-Origin Effects on Consumer Product Evaluation and Purchase Intention: The Role of Objective versus Subjective Knowledge. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2009, 21, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xunta de Galicia. Plan Estratégico del Xacobeo 2021. 2019. Available online: https://xacobeo2021.caminodesantiago.gal/es/institucional/plan-estratexico-do-xacobeo-2021 (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Turgalicia. Plan Director 2021–2023. Galicia Destino Seguro. 2021. Available online: https://www.turismo.gal/canle-institucional/turismo-de-galicia/a-axencia/plan-director-21-23-galicia-destino-seguro?langId=es_ES (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Comunidade Intermunicipal do Douro Estratégia Integrada de Desenvolvimento Territorial Da Região Do Douro (2014–2020). 2015. Available online: https://www.norte2020.pt/sites/default/files/public/uploads/programa/EIDT-99-2014-01-020_Douro.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Turismo de Portugal. Estratégia Turismo 2027; Turismo de Portugal: Lisboa, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lonely Planet. Spain and Portugal’s Best Trips; Lonely Planet Publications: Fort Mill, SC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Camagni, R.; Capello, R. Regional Competitiveness and Territorial Capital: A Conceptual Approach and Empirical Evidence from the European Union. Reg. Stud. 2013, 47, 1383–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capello, R. Cohesion Policies and the Creation of a European Identity: The Role of Territorial Identity*. JCMS 2020, 56, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, D.; Scott, A.J. Cultural Industries and the Production of Culture; Routledge Studies in International Business and the World Economy; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2004; ISBN 2004001844. [Google Scholar]

- Nogué, J.; de San Eugenio Vela, J. Geographies of Affect: In Search of the Emotional Dimension of Place Branding. Commun. Soc. 2018, 31, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, J.; Çakmak, E.; Dinnie, K. The Competitive Identity of Brazil as a Dutch Holiday Destination. Place Branding Public Dipl. 2011, 7, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Shen, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhong, X. Creating a Competitive Identity: Public Diplomacy in the London Olympics and Media Portrayal. Mass Commun. Soc. 2013, 16, 869–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Tomaney, J. What Kind of Local and Regional Development and for Whom? Reg. Stud. 2007, 41, 1253–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Hatch, M.J.J. The Dynamics of Place Brands: An Identity-Based Approach to Place Branding Theory. Mark. Theory 2013, 13, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raagmaa, G. Regional Identity in Regional Development and Planning 1. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2002, 10, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R. Territorial Capital, Competitiveness and Regional Development. In Handbook of Regions and Competitiveness; Huggins, R., Thompson, P., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 232–244. [Google Scholar]

- Nogué, J.; de San Eugenio Vela, J. The Visual Landscape’s Contribution to Generating Territorial Brands. Bol. Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2017, 2017, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, K.; Beunen, R.; Oliveira, E. Spatial Planning and Place Branding: Rethinking Relations and Synergies. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 1274–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guex, D.; Crevoisier, O. A Comprehensive Socio-Economic Model of the Experience Economy: The Territorial Stage. In Spatial Dynamics in the Experience Economy; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, J.; Pine, J. Authenticity: What Consumers Really Want; Harvard Business Press: Harvard, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bessière, J. Local Development and Heritage: Traditional Food and Cuisine as Tourist Attractions in Rural Areas. Sociol. Rural. 1998, 38, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, L.; Udall, D.; Franklin, A.; Kneafsey, M. Place-Based Pathways to Sustainability: Exploring Alignment between Geographical Indications and the Concept of Agroecology Territories in Wales. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development. AND-International Study on Economic Value of EU Quality Schemes, Geographical Indications (GIs) and Traditional Specialities Guaranteed (TSGs); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Paasi, A. Region and Place: Regional Identity in Question. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2003, 27, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, Z.; Mourão, J.C. Territorial Identity and Sustainable Development: From Concept to Analysis. Campus Soc. Rev. Lusófona Ciênc. Sociais 2004, 1, 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Haartsen, T.; Groote, P.; Huigen, P.P.P. Claiming Rural Identities: Dynamics, Contexts, Policies; Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Légaré, A. The Reconstruction of Inuit Collective Identity: From Cultural to Civic. The Case of Nunavut; Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International; Western University: London, ON, Canada, 2007; pp. 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Terlouw, K.; van Gorp, B. Layering Spatial Identities: The Identity Discourses of New Regions. Environ. Plan. A 2014, 46, 852–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, K. A Place Called Nunavut: Multiple Identities for a New Region; Barkhuis: Eelde, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, C. Ruimte Voor Identiteit: De Productie en Reproductie van Streekidentiteiten in Nederland. Ph.D. Thesis, Rjiksuniversiteit Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaney, J. Keeping a Beat in the Dark: Narratives of Regional Identity in Basil Bunting’s Briggflatts. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2007, 25, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlouw, K. Rescaling Regional Identities: Communicating Thick and Thin Regional Identities. Stud. Ethn. Natl. 2009, 9, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hague, C.; Jenkins, P. Place Identity, Participation and Planning; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; ISBN 0203646754. [Google Scholar]

- Hospers, G.-J. Four of the Most Common Misconceptions about Place Marketing. J. Town City Manag. 2011, 2, 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- McSweeney, B. Identity and Security: Buzan and the Copenhagen School; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerbauer, K. From Image to Identity: Building Regions by Place Promotion. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2011, 19, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaps, F.; Herrmann, S. Analyzing Cultural Markers to Characterize Regional Identity for Rural Planning. Rural. Landsc. Soc. Environ. Hist. 2018, 5, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, A. Illuminationg Regional Identity: An Interdisciplinary Exploration in Saskatchewan. Bachelor’s Thesis, Thompson Rivers University, Kamloops, BC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, C.; Huigen, P.; Groote, P. Analysing Regional Identities in the Netherlands. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2010, 101, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerbauer, K. Supranational Identities in Planning. Reg. Stud. 2017, 52, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gorp, B.; Terlouw, K. Making News: Newspapers and the Institutionalisation of New Regions. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2017, 108, 718–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. The Resurgence of the ‘Region’ and ‘Regional Identity’: Theoretical Perspectives and Empirical Observations on Regional Dynamics in Europe. Glob. Reg. Reg. Glob. 2009, 35, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitjar, R.D. Measuring Regionalism: Content Analysis and the Case of Rogaland in Norway. Reg. Fed. Stud. 2005, 15, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, R.; Go, F. Place Branding. Glocal, Virtual and Physical Identities, Constructed, Imagined and Experienced; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 9780230247024. [Google Scholar]

- Kalandides, A.; Kavaratzis, M.; Boisen, M.; Mueller, A.; Schade, M. Symbols and Place Identity: A Semiotic Approach to Internal Place Branding—Case Study Bremen (Germany). J. Place Manag. Dev. 2012, 5, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, H. Balancing between Thick and Thin Regional Identities. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2014, 7, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusman, I.; Lois-González, R. BuildingP Common Identities to Promote Territorial Development in the North of Portugal. In New Metropolitan Perspectives, Proceedings of the NMP 2020, Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, Online, 26–28 May 2020; Bevilacqua, C., Calabrò, F., della Spina, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1918–1927. [Google Scholar]

- Terlouw, K. Local Identities and Politics: Negotiating the Old and the New; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781138209251. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, L.A. Using the Past to Construct Territorial Identities in Regional Planning: The Case of Mälardalen, Sweden. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Solla, X.; Trillo Santamaría, J.M. Tourism and Nation in Galicia (Spain). Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 22, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronczyk, M. Branding the Nation: The Global Business of National Identity; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; ISBN 9780199752164. [Google Scholar]

- Semian, M.; Chromý, P.; Chromy, P. Regional Identity as a Driver or a Barrier in the Process of Regional Development: A Comparison of Selected European Experience. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. Nor. J. Geogr. 2014, 68, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquinelli, C. The Limits of Place Branding for Local Development: The Case of Tuscany and the Arnovalley Brand. Local Econ. 2010, 25, 558–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, S. Territory, Authority, Rights. From Medieval to Global Assemblages; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780691136455. [Google Scholar]

- Antonsich, M.; Holland, E.C. Territorial Attachment in the Age of Globalization: The Case of Western Europe. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2014, 21, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, X.M.; Lopez, L. Tourism Policies in A WHC: Santiago de Compostela (Spain). Int. J. Res. Tour. Hosp. (IJRTH) 2015, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lois González, R.C.; Castro Fernández, B.M.; Lopez, L. From Sacred Place to Monumental Space: Mobility Along the Way to St. James. Mobilities 2015, 11, 770–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusman, I.; Lopez, L.; Lois González, R.C.; Santos, X.M. The Challenges of the First European Cultural Itinerary: The Way of St. James. Almatour. J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 2017, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi, J.L. Xacobeo: The International Press’ Perception of the Way of St James (2009–2017). Methaodos Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2019, 7, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscarelli, R.; Lopez, L.; González, R.C.L. Who Is Interested in Developing the Way of Saint James? The Pilgrimage from Faith to Tourism. Religions 2020, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.F.; Riveiro, D. Estudio del Impacto Socioeconómico del Camino de Santiago; Universidad de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Solla, X.M.; Lois González, R.C. El Camino de Santiago en el Contexto de los Nuevos Turismos. Estud. Tur. 2011, 189, 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lois González, R.C. The Camino de Santiago and Its Contemporary Renewal: Pilgrims, Tourists and Territorial Identities. Cult. Relig. 2013, 14, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoza-Medina, X.; Lois González, R.C. Improving the Walkability of the Camino. In The Routledge International Handbook of Walking; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 390–402. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, J. A Situação Actual Do Sector Do Vinho Do Porto No Plano Empresarial. In História do Douro e do Vinho do Porto. O Vinho do Porto e o Douro no Século XX e Início do Século XXI; Guichard, F., Roudié, P., Pereira, G.M., Eds.; Afrontamento: Porto, Portugal, 2019; pp. 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, A.M.; Frazão-Moreira, A. Importance of Local Knowledge in Plant Resources Management and Conservation in Two Protected Areas from Trás-Os-Montes, Portugal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazenda, N.; da Silva, F.N.; Costa, C. Douro Valley Tourism Plan: The Plan as Part of a Sustainable Tourist Destination Development Process. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2010, 2, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, R.F.; Brito, C.M. Mutual Influence between Firms and Tourist Destination: A Case in the Douro Valley. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2014, 11, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lois González, R.; Santos, X. Tourists and Pilgrims on Their Way to Santiago. Motives, Caminos and Final Destinations. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2014, 6825, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Production (Litres) | Sales (Euros) | Average Price (Euros) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 131,752,869 | 498,771,604 | 3.8 |

| 2009 | 112,960,747 | 444,229,451 | 3.9 |

| ∆ 07/09 | −0.14 | −0.11 | 0.04 |

| 2011 | 111,281,371 | 455,589,128 | 4.1 |

| ∆ 09/11 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| 2013 | 111,357,571 | 482,314,384 | 4.3 |

| ∆ 11/13 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| 2015 | 115,487,955 | 508,650,708 | 4.4 |

| ∆ 13/15 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| 2017 | 122,195,264 | 553,524,763 | 4.5 |

| ∆ 15/17 | 0.06 | 0,09 | 0.03 |

| 2019 | 118,711,162 | 569,689,479 | 4.8 |

| ∆ 17/19 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gusman, I.; Sandry, A. The Economies of Identities: Recognising the Economic Value of the Characteristics of Territories. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8429. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148429

Gusman I, Sandry A. The Economies of Identities: Recognising the Economic Value of the Characteristics of Territories. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8429. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148429

Chicago/Turabian StyleGusman, Inês, and Alan Sandry. 2022. "The Economies of Identities: Recognising the Economic Value of the Characteristics of Territories" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8429. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148429

APA StyleGusman, I., & Sandry, A. (2022). The Economies of Identities: Recognising the Economic Value of the Characteristics of Territories. Sustainability, 14(14), 8429. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148429