Abstract

In recent decades, the interest in social innovation and nature-based solutions has spread in scientific articles, and they are increasingly deployed for cities’ strategic planning. In this scenario, participatory approaches become pivotal to engaging the population and stakeholders in the decision-making process. In this paper, we reflect on the first year’s results and the strengths and weaknesses—of the participatory activities realized in Lucca to co-design and co-deploy a smart city based on human–animal relationships in the framework of the European project Horizon 2020 (IN-HABIT). Human–animal bonds, as nature-based solutions, are scientifically and practically underestimated. Data were collected on the activities organized to implement a public–private–people partnership in co-designing infrastructural solutions (so-called Animal Lines) and soft nature-based solutions to be implemented in the city. Stakeholders actively engaged in mutual discussions with great enthusiasm, and the emergent ideas (the need to improve people’s knowledge of animals and develop a map showing pet-friendly services and places and the need for integration to create innovative pet services) were copious and different while showing many connections among the various points of view. At the same time, a deeper reflection on the relationships among the participatory activities and institutionally integrated arrangements also emerged.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the interest in social innovation has been growing among different stakeholdersaround the world, including researchers, academic institutions and policymakers [1,2], and several authors [3,4,5,6,7,8,9] have tried to define the concept from diverse point of views, though with the same outlook [10]. As underlined by the European Commission, social innovation is meant to “empower people, and drive change” in the sense that it leads to social change that produces sustainable solutions and social inclusion [11] and becomes a relevant tool to achieve a more participative and collective thinking.

Since the process of social innovation is, in many cases, based on participation, participatory approaches become pivotal to engage the population and stakeholders [12,13,14]. Indeed, participatory approaches have the objective of engaging people and promoting expression and communication of different groups of interest through open and democratic practices by considering all their viewpoints [15,16,17].

In the context of social innovation, the main expected outcome from the participatory modes of governance is to facilitate the implementation of sustainable development [18].

With regard to social innovation in the urban context, concepts such as nature-based solutions (NBS) are also increasingly implemented in cities’ strategic planning.

The term nature-based solutions is a wide concept that is increasingly spreading to mitigate the impacts of climate change, to conserve biodiversity and to improve human health and quality of life [19]. The definition of nature-based solutions given by the European Commission in 2016 is, “solutions that are inspired and supported by nature, which are cost-effective, simultaneously provide environmental, social and economic benefits and help build resilience. Such solutions bring more, and more diverse, nature and natural features and processes into cities, landscapes and seascapes, through locally adapted, resource-efficient and systemic interventions.” (https://ec.europa.eu/info/research-and-innovation/research-area/environment/nature-based-solutions_en, accessed on 18 May 2022).

The increasing debate on nature-based solutions is always seen as an essential part of cities’ development toward creating more sustainable landscapes [20] but also for their contribution in improving the wellbeing of the population [21]. As reported by different authors [22,23,24,25], indeed, the NBS concept includes various types of approaches aimed at the implementation of natural elements in urban areas with the goal of adapting to both climate change and other societal challenges.

The term “nature-based solutions” itself includes the main objective that these are aimed at achieving, namely, the creation of out-and-out concrete solutions to address societal challenges [26].

Nature-based solutions in urban environments have attracted increasing interest in recent years, with experiments in many urban areas to mitigate climate effects and increasing urban density in order to improve local wellness. Most of the reports and works on NBSs usually refer to solutions that are based on the use of plants to improve human wellbeing and mental health [27,28,29]. While the impact of animals on human psychological wellbeing is reported in many case studies, what is missing are nature-based solutions, which refers to the role of animals as NBS themselves and the enhancement of human–animal relationships (hum–animal) as a tool to increase the quality of life in cities. In the meantime, most urban areas are experiencing a growing presence of animals, both in families and cities [30,31,32,33]. The presence of animals (mainly pets) besides humans is still an unexplored topic, both from the social and economic points of view. The term “pet economy” has been recently introduced to elucidate the economic impact of such increasing human–animal interaction in the society. From the philosophical viewpoint, the debate between animal citizenship [34] and a more abolitionist approach [35] is also emerging. By following this societal trend, the Italian constitution recently introduced the rights of animals as part of citizenship rights.

One of the few articles that refer to animals as NBS is that of Danby and Grajfoner [36], in which they tried to critically analyze the human–equine touristic experiences and how they can be recognized as nature-based solutions for mutually enhancing psychological wellbeing. From this study, the authors could deduce how the nonhumans are a fundamental part of nature-based solutions to increase human wellbeing and mental health thanks to an active mutually agreed relationship between humans and nonhumans formed within natural spaces.

The identification of innovative and integrated solutions to promote health and wellbeing in cities is the main aim of the European project Horizon 2020. This project actively involves local population and stakeholders in the creation of solutions and in decisional processes through different participatory approaches.

The case study presented in this paper refers to the European project Horizon 2020 concerning the city of Lucca, Italy. The project, called “IN-HABIT—INclusive Health and wellBeing In small and medium size ciTies”, involves four European cities—Cordoba (Spain), Riga (Latvia), Lucca (Italy) and Nitra (Slovakia)—and it aims at increasing inclusive health and wellbeing through the mobilization of existing undervalued resources (culture, food, human–animal bonds and environment).

The main objective in the Lucca case is to create the first human–animal (hum–an) smart city in Europe, with an integrated human–animal policy able to mobilize such resources in order to increase local wellness for less empowered people and for all citizens. The project intends to work on the different aspects of human–animal relationships to achieve innovative solutions on the topic. Starting from the recognition of the importance of this relationship for the wellbeing of citizens, it aims to build an integrated policy of actions in the different fields of intervention (urban planning, social field, culture, economic field, tourism, etc…).

From the beginning of the project, special attention was given to the involvement of people through participatory processes, since it is important that the solutions are co-designed, co-deployed and co-managed with and by local stakeholders. The process facilitated the co-design of innovative solutions to be introduced in the territory of Lucca

The aim of this work is to report as well as to reflect upon the first findings of one-year co-design activities organized along a participative path and to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the methodology implemented. The objective of this work is, moreover, to analyze and reflect on facilitating aspects and bottlenecks of the process carried out in order to understand how these will have to be overcome in the future to reach a better relationship between private and public subjects and to better align participatory processes with institutional adaptations.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology used in this case study has been the creation of public–private–people partnerships (PPPPs) involving active citizens and stakeholders of the city of Lucca.

The interest in public–private–people partnerships has increased over the last decade, and they are seen as instruments for coordinating and aligning the viewpoints and efforts from different sectors. Due to the active involvement of different socio-economic actors and public institutions [37], this methodology can be used to share information across different sectors [38] to solve defined shared problems. The aim of such partnerships is to empower citizens who can share their awareness of their territory [16], hence becoming co-designers, co-producers and co-evaluators [37]. The PPPPs model attempts to involve the whole community in the urban processes warranting the consideration of the contribution and the competencies of each stakeholder [37].

Therefore, the public–private–people partnerships (PPPPs) method is a fully fledged tool to involve people working together in the co-creation of new services, policies and innovation processes [39].

The process from which we obtained some preliminary research findings can be divided into two phases and two pillars (Table 1): an external participatory approach and an internal one, more closed inside the different parts of the municipality of Lucca. In the first pillar, two phases can be distinguished. In the first phase, different meetings were held aimed at co-designing in the city’s innovative infrastructures—the so-called “Animal Lines”; the second-phase meeting was dedicated to creating a dialog among participants on innovative “soft” solutions (Table 2).

Table 1.

Pillars and co-design areas in the overall participatory process in Lucca.

Table 2.

Pillar one: citizens’ participatory process in Lucca.

In the second pillar, in parallel with the first one, the process inside the public administration represented by Lucca municipality was also deployed, in order to facilitate the interface with the participatory activities (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pillar two: institutional participatory process in Lucca municipality.

The two phases of the two pillars are obviously interlinked.

In our study, the first phases of the two pillars were used to allow the city to co-design together with its community innovative infrastructures, solutions and services between political and research institutions and different stakeholders of the territory.

In pillar one phase one, the organization and development of the participatory process were mainly managed by the team of researchers of the University of Pisa (UNIPI) involved in the project with the help of the municipality of Lucca and Lucca Crea—the other two partners of the project.

Before starting with the meetings, some selection criteria to establish the actors to be involved were defined: 1. the PPPP scheme had to be properly represented with the involvement of people, private and public entities; 2. stakeholders should live in Lucca; 3. a gender, diversity, equity and inclusion approach should be considered; 4. stakeholders dealing with the theme of animals were required.

Since the use of the human–animal bond (“The human-animal bond is a mutually beneficial and dynamic relationship between people and animals that is influenced by behaviors essential to the health and wellbeing of both. This includes, among other things, emotional, psychological, and physical interactions of people, animals, and the environment.” (The American Veterinary Medical Association. The human–animal interaction and human–animal bond. Available at: https://www.avma.org/one-health/human–animal-bond, accessed on 18 May 2022) as a means of improving people’s inclusion and well-being is an innovative topic, especially if linked to the urban environment, the UNIPI team decided to organize various previous meetings with Lucca’s councilors of different departments (social policies, education, tourism, environment, public works). The aim of the meetings was to introduce the councilors to the project and to be able to increase awareness and to generate a common understanding around the topic and the possible features and applications (pillar two, phase one).

Globally, the first phase of the PPPPs method began in February 2021 and ended in May 2021.

In pillar one, seven specific co-creation workshops were designed to stimulate the discussion around innovative business solutions linked to the different themes. Due to COVID-19 pandemic, these meetings were held mostly online, with only one in person. About 80 stakeholders took part in the meeting during this phase, and they were citizens, professionals—pet-care sector and educators—and associations.

During the first workshops aimed at introducing the IN-HABIT project to Lucca’s citizens, the concept vision of the project, the main topics and a proposal for future actions and solutions to be deployed were presented. These events were crucial to engage different stakeholders: active citizens, stakeholders from different fields of interest and, through the help of social tables of marginality and disability, people at risk of exclusion.

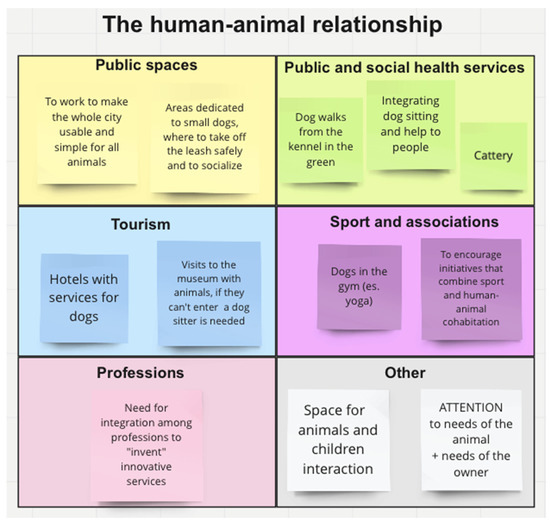

During the following workshops, participants shared their opinions about the human–animal bond and what kind of sustainable innovative solutions could be developed to improve the quality of this interaction. To encourage participants in the discussion and development of the innovative ideas, the workshops were held with the help of specific tools, such as a virtual board (Figure 1)—which worked in place of traditional post-it notes—and an online app called “Mentimeter” to ask the participants some ice-breaking questions. The aim of these meetings was to collect opinions and suggestions to make Animal Lines as much as suitable as possible to the needs of the territory and accessible to everyone.

Figure 1.

Virtual board and some of the ideas that emerged during the meeting.

In parallel with the external participatory process, within the Lucca municipality, the project of the Animal Lines was accompanied, technically facilitated and prepared according to the results of the workshops. The facilitation process focused on the suitable intervention areas (belonging to the Lucca municipality and not yet finalized for other purposes), the budget that could be allocated in accordance with the research project, as well as the suitable architectural solutions from the human–animal point of view.

The last meeting of this phase, held in person, linked the two phases of the two pillars and consisted of an ecological walk in the selected suitable areas where the two main infrastructures of the Animal Lines are going to be built. During the eco-walk, additional suggestions from participants were also collected to finalize the project.

The second phase of the process started in January 2022 and, as researchers thought it would have been more productive to have separate discussions on different topics, a methodology of work in five separated thematic groups was chosen. The selected topics for these groups were: (1) Social sector; (2) Professionals (pet care); (3) Tourism sector; (4) Citizen; (5) Education.

A workshop was held. The online meeting was led by the researchers of the University of Pisa. The three-hour workshop was attended by 50 people, and it was divided into three parts: (a) Plenary session with a small introduction to again present the project and to explain the organization of the meeting; (b) Discussion on the topics—division of participants into working groups; (c) Plenary session with presentation of results of the discussions in each group.

Each room for the groups was moderated by a researcher from the University of Pisa accompanied by another person (from the University of Pisa or the Municipality of Lucca) who took the minutes of the discussion. The activity allowed researchers of the University of Pisa to collect ideas about possible solutions to be implemented in the city and ways of developing them.

In parallel, and soon after, in the second pillar, direct meetings with each political sector of the municipality were organized to better match the coherence between the emerging soft solutions as well as the existing policies and organization. The objective of this action was to translate the old schemes for public intervention into the new ones.

3. Results

The overall designed methodology fit adequately with the process and was favorably received by participants. The PPPPs approach allowed us to understand the main features and needs of the territory and to fix the most important aspects to be considered in the design of the “Animal Lines”—the infrastructural solutions of the project. It also managed to bring together different stakeholders to start discussing the main actions to be implemented in the territory. Most of the starting efforts were devoted to the external participatory process, but in the meantime, and soon after, it emerged clearly that without an internal animation and a negotiation process within the municipality, the effectiveness of the overall process could be penalized (pillar two), and the PPPP itself could move on with difficulties and asymmetries.

3.1. Results of the First Phase

The first phase is the most relevant part of the process and led to more detailed results, as planned already in the research project.

In pillar one (external process), from the discussion emerged the idea of promoting meetings to increase awareness among citizens on animals’ wellbeing linked to the urban environment and the need for integration between different professions to create innovative pet services. A specific workshop was devoted to asking people to imagine what could be the two different scenarios (a positive and a negative one) in the future after the IN-HABIT project, and interesting opinions emerged.

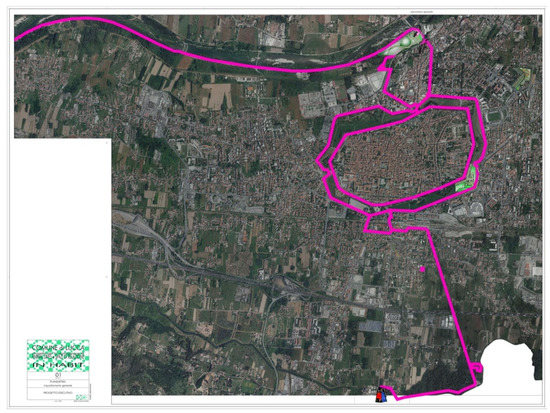

As mentioned, this first phase of the process was dedicated to the co-design of the so-called “Animal Lines”—a path that would link the old city center (corresponding to the city’s ancient walls and the under-utilized surrounding green areas) with Lucca’s suburbs and peri-urban areas. Different areas accessible to people and their pets are planned to be built along the path.

The participative process within the community helped in gathering the information, needs and ideas about what to implement inside the areas, what materials to use to create an accessible place and how to make the areas comfortable for both people and their pets.

In connection with the internal process at municipality level, the external participatory activities identified a route that goes from the “Parco Fluviale del Serchio” from the north, arrives in the city passing through the urban walls and the “Spalti” (green areas that surround the walls) and then goes south to the “San Concordio” district and the “Acquedotto Nottolini”, a path with both naturalistic–environmental and monumental value (Figure 2). Along this route, simple interventions will be implemented to adapt the existing cycle paths or pedestrian paths to become more pet friendly.

Figure 2.

Animal Lines path (in purple lines).

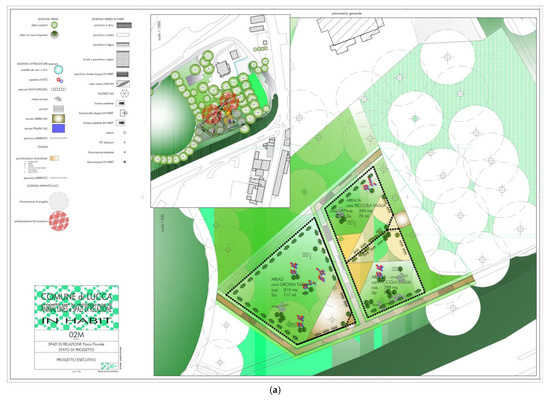

The project also provides for the creation of spaces where the human–animal relationship and, consequently, social relations and inclusion of the most fragile subjects would be facilitated. They will not simply be fenced areas for the traditional “walking” of dogs but spaces also equipped with benches and shade, where relationships between humans and their pets, but also with other people and other animals, can be fostered.

According to what emerged in the participative process and with the support of the technical and administrative process held in pillar two, Animal Lines will have areas where it will be possible to carry out activities (Figure 3a,b) such as animal-assisted interventions (AAI)—especially aimed at categories of people with special needs—and sports activities with pets. Since the areas will be equipped with facilities that could also be used by people with disabilities, activities in collaboration with professionalism in the pet field for educational events and more could be performed.

Figure 3.

(a) Boards of the two areas along Animal Lines: the “Parco Fluviale” area. (b) Boards of the two areas along Animal Lines: the area behind the old hospital.

The areas that will be built were all chosen based on their accessibility (presence of a car park area, accessibility for people with disabilities) and their proximity to the path of the Animal Lines.

All interventions were designed in such a way as to minimize the environmental impact using natural materials. At this stage (May 2022), a public call was launched by the municipality, and the selection of builders for the deployment is ongoing.

3.2. Results of the Second Phase

The second phase was very useful to start exploring the ideas presented and thinking about their development, though at a very early stage. These ideas will be further explored by working groups over the next years, according to a cumulative process, and they will become the subject of further works. Table 4 presents the most relevant ideas that emerged during the first meeting.

Table 4.

Ideas that emerged during the meeting from each working group and subjects to be involved.

In the “active citizenship” group, the need to improve people’s knowledge about animals, both pets and wild, emerged first. This could be realized through different actions with the involvement of schools organizing meetings and playful activities for students aimed at understanding the correct human–animal relationship. Focusing on the improvement of awareness of pets, during the meeting, citizens spoke about the possibility of organizing educational activities for those who want to acquire a dog, well-defined itineraries for those who want to walk with their pet and different types of educational events in the spaces of the Animal Lines. With regard to wild animals, the idea emerged of involving biologists and wildlife experts to organize field trips to learn about local wildlife and workshops open to citizens to understand the ethology of animals. Some other interesting ideas proposed by the citizens’ group focused on improving the public spaces for pet management, also through the creation of a dog-sitters network through voluntary action and specific projects for the elderly, people with mobility difficulties, etc. The connection among the activities and pivotal physical points, such as Animal Lines but also public kennels, schools and neighboring farms, was also pointed out.

The group on tourism was very motivated and, during the meeting, defined the steps needed to develop a map showing pet-friendly services and places with a logo to identify them. They thought about a primary check of the facilities—for example accommodation facilities, restaurants, cultural institutes—near the path of the Animal Lines, which already are pet friendly/or willing to join the network. As a second step, the need emerged to define the basic requirements that the facilities must have to request the logo created to have this service recognized. As a further action, people discussed involving schools or graphic designers by profession to create the specific logo.

The group on social aspects focused the discussion on the theme of pets and elders, and different ideas emerged. They spoke about the possibility of inviting dog educators to work together with associations in support of animals and associations in support of the elderly to create new types of home care services, extending the range of activities also to animals but also focusing on nursing homes and the possibility of opening access to animals. In addition to this, other applications of the innovative NBS for young people without families, NEETs and children with autism were also discussed.

The group working on education focused on the theme of animals in schools and educational events aimed at raising awareness about animals and how to approach them in schools. The idea from the group was introducing the animal and then talking about it together. People discussed the possibility of organizing these events with animals in flesh and blood, but if it becomes difficult to bring animals into schools, the activity could perhaps be executed through playing with an image or a soft toy. The need to involve high schools as a tool for implementing certain initiatives, such as school-work alternation projects or the creation of specific routes for tourists or citizens with animals, also emerged, aiming at increasing positive attitudes to voluntary activities in youngsters. To meet this need, educators considered several actions to make students protagonists, for example, creating partnerships between the school and tourism sectors but also collaborations with museums.

Professionals of pet care discussed together the opportunity to implement different types of services, such as dog sports incentives and services for non-dog species, as well as creating a platform of pet-friendly services and organizing educational projects for various ages. From their point of view, this goal could be achieved by identifying properly the areas and type of intervention, organizing open days, demonstrations and fairs, and promoting actions through digital communication and advertising.

After such participatory meeting, the complexity in the possible human–animal nature-based solutions emerged. On the one hand, it enabled the political actors to see the topic as capable of attracting societal attention and political consensus. On the other hand, some technical doubts about how to support the emerging ideas from the municipality point of view started to arise, especially among the technical staff. To avoid any possible clash, the internal process of animation was supported by the municipality in order to avoid and reduce any possible routinary barriers and to facilitate the organization of converging ideas between the existing policies and practices and the new emerging solutions, also in an integrated way.

4. Discussion

The case study focused on diverse elements, such as the social innovation process in order to mobilize unexpected resources, such as animal nature-based solutions, as well as the process held to organize a PPPP on a specific topic. In such an arena for discussion, the co-design process should be understood as an overview of different and mutually interacting dimensions, internally (to the administration) and externally, between it and the other local, private and people components.

In the external pillar, during the participatory processes, all the proposed ideas were discussed by different stakeholders, taking into consideration the needs of their city (the lack of knowledge and education of citizens on animals, the need to improve public spaces for pet management, etc.) and some possible innovative solutions able to resolve the emerging challenges. This process was aligned with the internal municipality support, which was able to facilitate the external process by offering clear technical solutions able to accommodate the participatory game. From this point of view, the PPPP was accommodated, according to the two pillars, in quite a synchronic and effective way.

From the first phase of the process, from both pillars, the evident result emerged in the co-design of the Animal Lines’ project, which is now in the phase of deployment.

During the co-design meeting of the second phase (pillar one), the people actively interacted, and with the moderators’ support, they discussed their ideas for innovative solutions on the topic. Although in this second phase, the participation of various stakeholders was split into five working groups on different topics, many ideas turned out to be common, providing evidence of real connections between the various groups and topics within the project.

All the innovative ideas elaborated by various stakeholders provided a clear definition of the needs of the territory and a convergence of solicitations on the same initiatives that could therefore arouse integrations between the various groups of interest.

We can see this, for example, in both citizens and education groups, where the need to improve the knowledge and education of citizens on animals (both pet and wild), to sensitize children and school students of all grades to the human–animal relationship and the right behavior towards specific pets, has emerged. This idea, in some ways, also came out in the pet care group, with the need for educational projects addressed to targets of various ages, including children in schools with the involvement of teachers. Among the target groups of these projects, elderly people could also be included and, as another proof of connection, also in the social group, various stakeholders opened the discussion about the creation of processes that would facilitate new services in collaboration with dog educators.

Another common idea between two different groups of stakeholders was the need for specific services for tourists that emerged both in the education and tourism groups. The education group thought about partnerships between schools and the tourism sector to create specific routes for tourists or citizens with animals. At the same time, in the tourism sector group, speaking about the development of a map showing pet-friendly services and places with a logo to identify pet-friendly services, the idea of involving schools in the creation of the logo emerged.

In addition to this, a participatory process might run the risk of being frustrated when it does not match with a parallel process among the public actors. To avoid such a risk, an internal animation in the municipality took place to better facilitate and align the technical and political councilors of the diverse sectors involved to the new path. This part of the process is still ongoing in order to give legs to the process and to move on from ideas to their possible application in connection between the public sector, private sector and ordinary citizens in the organization of an ever increasing partnership able to mobilize the new topic and to increase wellness in Lucca city.

The case study in Lucca showcases, to a great degree, during such a particular period, a set of factors that can reveal potential enablers and obstacles in the activation of PPPPs and of participatory processes of co-design in the territory.

The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly represented one main obstacle. This situation heavily conditioned the whole process; it led to the postponement of some events, and it forced the organization of several activities through a virtual modality. It can be easily stated how participatory processes require in-person operating methods to achieve the best possible outcome, and therefore, the complication in the organization of meetings in person slowed down and invalidated the process to a considerable extent. The ability to adapt to the pandemic situation and the new habits it generated allowed us to adapt the processes according to the new virtual modalities though.

While not without difficulties, the activities, mainly online, were held in a relaxed atmosphere, and they turned out to be productive, bringing to light many points of view and several useful outcomes, also thanks to a strong methodological support and tools. The declarations of the participants and the numerous outcomes derived from the discussion indicate that the proposed method, even not in a classic situation, effectively facilitated experience sharing among the participants.

In addition to this part of the process, our experience opens up a point of reflection on the feasibility of innovative PPPPs without specific attention given to the internal changes in public administrations. Normally, most of the attention is given to the involvement of the private sector and ordinary citizens, often taking for granted the co-operation of the public entities. The process seems to be more complex, as the ability to introduce new ideas and concepts might collide with existing ones, and this occurs more often when routines are more consolidated, as in the public offices. From this point of view, specific attention should be paid to two aspects.

The first one is related to the political evidence of the innovative solutions at stake. This can be lower when the topic at stake is more innovative, such as for human–animal solutions. From this point of view, the success of participatory processes might reinforce the political use of the new topic, and this might ensure the political support for the whole process. Without this step, the participatory process might be frustrated, and it can become a useless exercise, with many nice but not yet applicable ideas.

On the other hand, still inside the administration, the political support might not be enough without the active, and sometimes pro-active, engagement of the technical staff. The achievement of this outcome is not an easy task, but it can be facilitated by translating the new topic and the emerging solutions into existing tasks for the different areas of the public administration. From this point of view, a process that is seen as lateral and sometimes as an extra effort for the technical staff might become facilitated with the achievement of specific goals, such as new services and health improvement for the social sector, new market niches for tourism and local businesses, innovative activities for schools and educational processes, emerging activities for the overall citizens and people. To facilitate such an outcome, strong facilitation should be ensured to negotiate, share, define converging paths and to translate the old into the new practices. When this occurs, an alignment between the public sector, private sector and the general public can emerge, although after many efforts and risks of vicious circles. In such a perspective, the alignment between participation, politicians and technical staff might lead to new integrated policies. Such alignment, in the case of the Lucca IN-HABIT process, is still a possible perspective, although some fertile seeds seem to be in the ground.

The introduction of an innovative approach, such as nature-based solutions related to human–animal bonds, emerged as particularly demanding in terms of awareness raising among diverse stakeholders, both at the administrative level as well as in Lucca city. The research topic, therefore, represented a challenge to be overcome. Firstly, it is necessary to have an adequate “sub-layer” of actors available to become involved and to review their values and priorities in order to change their own behaviors. This can only be achieved through preliminary work of co-creating knowledge and raising awareness on the opportunities offered by the human–animal bond to improve the wellbeing and social inclusion.

When working on an innovative project, such as the IN-HABIT, with the prospect of developing new policies and services, the role of public administrations becomes decisive and, above all, their effectiveness in making the innovations that emerge from the participatory process concrete and operational becomes crucial. When the steps, times and efforts of public administrations do not move at the same pace as societal demands and solutions emerging from participatory exercises, the risk of a slowdown of the process and of dissatisfaction and alienation of citizens grows, and this generates frustration for further social innovation processes.

5. Conclusions

Social innovation, nature-based solutions and PPPPs are emerging as useful topics to face the emerging challenges in our society. In our work, all the three were applied to the introduction of human–animal bonds in order to increase the enhancement of public health in public spaces in cities. Animal nature-based solutions, Animal Lines—as innovative public infrastructures—and soft human–animal solutions were co-designed, and they are going to be co-deployed in Lucca via participatory methods.

The aim of this work is related to the first findings of one-year participative co-design activities from the Lucca case. According to this path, stakeholders actively participated with a great enthusiasm in the participative process. This can be seen as proof of how public involvement is a crucial point in the new governance development. It is able to define new solutions and activities when rightly mobilized toward facilitating methods. From this point of view, the number and the variety of ideas were copious and different, even if showing many connections between the various groups of interest. Diversity, interconnection and practicability might be seen as indicators of the effectiveness of the participatory process. At the same time, participation might not offer real innovation without administration—political and technical—engagement. From this point of view, the research action process might find the aim of the researchers as being able to push the process when bottlenecks arise. The political engagement as well as the involvement of the public technical staff might generate bottlenecks when they work asynchronously with the participatory process. Emphasis should be placed on this aspect in order to avoid any risks of failure within the social innovation processes, especially when the topics are far from the mainstream, as in the Lucca case. The leadership of the process needs to be well aware and motivated regarding the risks and possible paths to achieve suitable solutions.

From a methodological point of view, the main outcome of our reflection is related to the demand to link participative methodologies to internal public institutional and political changes in order to move forward to innovative policies’ design. This is particularly true for well innovative topics, such as nature-based solutions rooted in the promotion of the human–animal bond to support the quality of life in challenging cities and society.

Author Contributions

The research group was coordinated by F.D.I. with the support of C.M. Conceptualization, G.G. and C.B. (Carmen Borrelli); Methodology, G.G., C.B. (Carmen Borrelli), R.M., M.R., F.R., C.B. (Carlo Bibbiani) and F.D.I.; Writing—original draft, G.G.; Writing—review and editing, G.G., C.B. (Carmen Borrelli), R.M., M.R., F.R. and F.D.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 869227.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Pisa (protocol No. 30/2021-24 September 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants and partners in the study, Simurg Ricerche for the help in the facilitation of the participatory processes and the architect Diletta Moretti for the project’s design of the “Animal Lines”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Audretsch, D.B.; Eichler, G.M.; Schwarz, E.J. Emerging Needs of Social Innovators and Social Innovation Ecosystems. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2022, 18, 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, R.; Tuertscher, P.; van de Ven, A.H. Perspectives on Innovation Processes. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2013, 7, 775–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bignetti, L.P. As Inovações Sociais: Uma Incursão Por Ideias, Tendências e Focos de Pesquisa. Ciências Sociais Unisinos 2011, 47, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonifacio, M. Social Innovation: A Novel Policy Stream or a Policy Compromise? An EU Perspective. Eur. Rev. 2014, 22, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatfield, A.T.; Reddick, C.G. Smart City Implementation Through Shared Vision of Social Innovation for Environmental Sustainability: A Case Study of Kitakyushu, Japan. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2016, 34, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; Martinelli, F.; González, S.; Swyngedouw, E. Introduction: Social Innovation and Governance in European Cities: Urban Development Between Path Dependency and Radical Innovation. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2007, 14, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.; Caulier-Grice, J.; Mulgan, G. The Open Book of Social Innovation; The Young Foundation/Nesta: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 9781848750715/1848750714. [Google Scholar]

- Nyseth, T.; Hamdouch, A. The Transformative Power of Social Innovation in Urban Planning and Local Development. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phills, J.A.; Deiglmeier, K.; Miller, D.T. Rediscovering Social Innovation. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2008, 6, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos Figueiredo, Y.D.; Prim, M.A.; Dandolini, G.A. Urban Regeneration in the Light of Social Innovation: A Systematic Integrative Literature Review. Land Use Policy 2022, 113, 105873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fougère, M.; Segercrantz, B.; Seeck, H. A Critical Reading of the European Union’s Social Innovation Policy Discourse: (Re)Legitimizing Neoliberalism. Organization 2017, 24, 819–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauppenlehner-Kloyber, E.; Penker, M. Between Participation and Collective Action—From Occasional Liaisons towards Long-Term Co-Management for Urban Resilience. Sustainability 2016, 8, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McConnell, A.; Drennan, L. Mission Impossible? Planning and Preparing for Crisis. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2006, 14, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonyo, S.B.; Fleming, C.S.; Freitag, A.; Goedeke, T.L. Resident Perceptions of Local Offshore Wind Energy Development: Modeling Efforts to Improve Participatory Processes. Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathe, S. Integrating Participatory Approaches into Social Life Cycle Assessment: The SLCA Participatory Approach. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2014, 19, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marana, P.; Labaka, L.; Sarriegi, J.M. A Framework for Public-Private-People Partnerships in the City Resilience-Building Process. Saf. Sci. 2018, 110, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovan, W.R.; Murray, M.; Shaffer, R. Participatory Governance Planning, Conflict Mediation and Public Decision-Making in Civil Society, 2017th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal-Clayton, B.; Bass, S. Sustainable Development Strategies: A Resource Book; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 9781853839474. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Walters, G.; Janzen, C.; Maginnis, S. Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature): Gland, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-2-8317-1812-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tayefi Nasrabadi, M. How Do Nature-Based Solutions Contribute to Urban Landscape Sustainability? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; van den Bosch, M.; Lafortezza, R. The Health Benefits of Nature-Based Solutions to Urbanization Challenges for Children and the Elderly—A Systematic Review. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, C.; Brillinger, M.; Guerrero, P.; Gottwald, S.; Henze, J.; Schmidt, S.; Ott, E.; Schröter, B. Planning Nature-Based Solutions: Principles, Steps, and Insights. Ambio 2021, 50, 1446–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Collier, M.J.; Kendal, D.; Bulkeley, H.; Dumitru, A.; Walsh, C.; Noble, K.; van Wyk, E.; Ordóñez, C.; et al. Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Climate Change Adaptation: Linking Science, Policy, and Practice Communities for Evidence-Based Decision-Making. BioScience 2019, 69, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Hansen, R. Principles for Urban Nature-Based Solutions. Ambio 2022, 51, 1388–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortezza, R.; Chen, J.; van den Bosch, C.K.; Randrup, T.B. Nature-Based Solutions for Resilient Landscapes and Cities. Environ. Res. 2018, 165, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafortezza, R.; Sanesi, G. Nature-Based Solutions: Settling the Issue of Sustainable Urbanization. Environ. Res. 2019, 172, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond, C.M.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Kabisch, N.; Berry, P.; Breil, M.; Nita, M.R.; Geneletti, D.; Calfapietra, C. A Framework for Assessing and Implementing the Co-Benefits of Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Areas. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 77, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Jagt, A.P.N.; Smith, M.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Konijnendijk, C.C.; Giannico, V.; Haase, D.; Lafortezza, R.; Nastran, M.; Pintar, M.; Železnikar, S.; et al. Co-Creating Urban Green Infrastructure Connecting People and Nature: A Guiding Framework and Approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujcic, M.; Tomicevic-Dubljevic, J.; Grbic, M.; Lecic-Tosevski, D.; Vukovic, O.; Toskovic, O. Nature Based Solution for Improving Mental Health and Well-Being in Urban Areas. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, A. The More-than-Human City. Sociol. Rev. 2017, 65, 202–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, W.; Wiesel, I.; Maller, C. More-than-Human Cities: Where the Wild Things Are. Geoforum 2019, 106, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, P.; Brooks, A. Animals and Urban Gentrification: Displacement and Injustice in the Trans-Species City. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 45, 1490–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcari, P.; Probyn-Rapsey, F.; Singer, H. Where Species Don’t Meet: Invisibilized Animals, Urban Nature and City Limits. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2021, 4, 940–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S.; Kymlicka, W. Zoopolis: A Political Theory of Animal Rights; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0199673018. [Google Scholar]

- Francione, G.L.; Charlton, A. Animal Rights: The Abolitionist Approach; Exempla Press: Newark, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Danby, P.; Grajfoner, D. Human–Equine Tourism and Nature-Based Solutions: Exploring Psychological Well-Being through Transformational Experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2022, 46, 607–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniotti, C. The Public–Private–People Partnership (P4) for Cultural Heritage Management Purposes. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Lindkvist, C.M.; Temeljotov-Salaj, A. Barriers and Potential Solutions to the Diffusion of Solar Photovoltaics from the Public-Private-People Partnership Perspective—Case Study of Norway. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herselman, M.; Marais, M.; Pitse-Boshomane, M. Applying living lab methodology to enhance skills in innovation. In Proceedings of the eSkills Summit 2010, Cape Town, South Africa, 26–28 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).