Sustainable Development Goals and 2030 Agenda—Survey on Awareness, Knowledge and Attitudes of Italian Teachers of Public Mandatory Schools, 2021

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. National Policy on Sustainability and Education

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

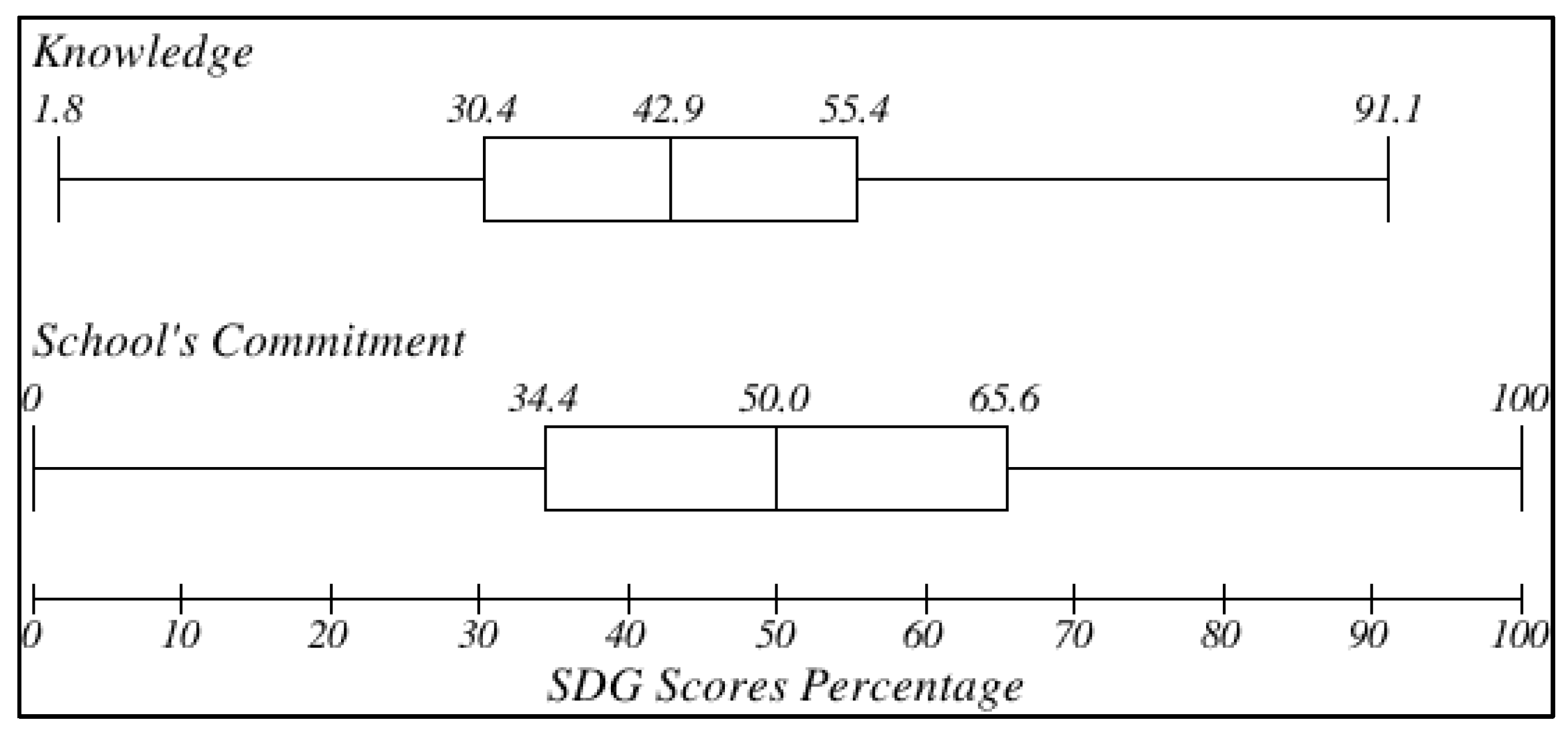

3.2. Knowledge

3.3. Sources of Information

3.4. Attitudes

3.5. Schools’ Commitment to Integrating Sustainability into Didactic Activities

3.6. Scores and Association

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Transforming Our World—Literacy for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000234253 (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- UN. Indicators of Sustainable Development: Guidelines and Methodologies—Third Edition. 2017. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/natlinfo/indicators/guidelines.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Sachs, J.D. From Millennium Development Goals to Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet 2012, 379, 2206–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Council resolution A/HRC/35/23 on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Physical and Mental Health in the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2017. Available online: https://www.right-docs.org/doc/a-hrc-res-35-23/ (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- World Health Organization. WHO Regional Committee for Europe resolution EUR/RC66/R4. Towards a Roadmap to Implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in the WHO European Region. 2016. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/319096/66rs04e_SDGs_160763.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- World Health Organization. WHO Regional Committee for Europe Resolution EUR/RC66/R7. Action Plan for Sexual and Reproductive Health: Towards Achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in the WHO European Region—Leaving No One Behind. 2016. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/319114/66rs07e_SRH_160767.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- World Health Organization. Sixty-Sixth World Health Assembly, 2013. World Health Assembly Resolution WHA66.11. Health in the Post-2015 Development Agenda. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA66-REC1/WHA66_2013_REC1_complete.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- World Health Organization. Sixty-Seventh World Health Assembly, 2014. World Health Assembly Resolution WHA67.14. Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_14-en.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- World Health Organization. Sixty-ninth World Health Assembly, 2016. World Health Assembly Resolution WHA69.1. Strengthening Essential Public Health Functions in Support of the Achievement of Universal Health Coverage. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_R1-en.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- World Health Organization. Sixty-Ninth World Health Assembly, 2016. World Health Assembly Resolution WHA69.11. Strengthening Synergies between the World Health Assembly and the Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_11-en.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Kickbusch, I.; Hanefeld, J. Role for academic institutions and think tanks in speeding progress on sustainable development goals. BMJ 2017, 358, 3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Waage, J.; Yap, C.; Bell, S.; Levy, C.; Mace, G.; Pegram, T.; Unterhalter, E.; Dasandi, N.; Hudson, D.; Kock, R.; et al. Governing the UN Sustainable Development Goals: Interactions, infrastructures, and institutions. Lancet 2015, 3, E251–E252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations General Assembly—Resolution 57/254 United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. 2002. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/a57r254.htm (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Plan of Implementation of the World Summit on Sustainable Development. 2002. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/WSSD_POI_PD/English/WSSD_PlanImpl.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Ministero Dell’ambiente e Della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare—Strategia Nazionale per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile. Available online: http://ricerca-delibere.programmazioneeconomica.gov.it/media/docs/2017/E170108Allegato1.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Sterling, S. Sustainable Education—Re-Visioning Learning and Change; Schumacher Society Briefing No. 6; UIT Cambridge Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Framework for the Implementation of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) beyond 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/sites/default/files/40_c23_framework_for_the_implementation_of_esd_beyond_2019.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Education for Sustainable Development Goals—Learning Objectives (2017). Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Shulman, L.S. Knowledge and teaching—Foundation of the new reform. Harv.Educ.Rev. 1987, 57, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Sustainable Development Begins with Education. How Education can Contribute to the Proposed Post-2015 Goals. 2014. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/2275sdbeginswitheducation.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development—A Roadmap. 2020. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802 (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Ministero Dell’istruzione, Dell’università e Della Ricerca; Ministero dell’Ambiente, Della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare. Protocollo D’intesa R.0000020.06-12-2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.mite.gov.it/sites/default/files/archivio/allegati/trasparenza_valutazione_merito/protocollo_miur-mattm.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Gazzetta Ufficiale Della Repubblica Italiana. DPCM 11 Feb 2014 n.98. 2014. Available online: https://www.istruzione.it/allegati/2014/DPCM_98_2014.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Ministero Dell’istruzione, Dell’università e della Ricerca; Ministero Dell’ambiente, della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare. Carta sull’Educazione ambientale e lo Sviluppo Sostenibile. 2016. Available online: https://www.mite.gov.it/sites/default/files/archivio/allegati/educazione_ambientale/documento_tavolo2_svilupposostenibile_rev7.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- MIUR. ASviS. Piano per l’Educazione alla Sostenibilità. 2017. Available online: https://asvis.it/public/asvis/files/sostenibilita_slide_def.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Scuola 2030–Educazione per la Creazione di Valore. Available online: https://scuola2030.indire.it/ (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- MIUR. Linee Guida per L’insegnamento Dell’educazione Civica. 2020. Available online: https://www.miur.gov.it/documents/20182/0/ALL.+Linee_guida_educazione_civica_dopoCSPI.pdf/8ed02589-e25e-1aed-1afb-291ce7cd119e?t=1592916355306 (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Gazzetta Ufficiale Della Repubblica Italiana (GU Serie Generale n.195 21-08-2019). Legge 20 Agosto 2019, n.92. 2019. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2019/08/21/19G00105/sg (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- MIUR. L’Educazione Civica—Un Percorso per Formare Cittadini Responsabili. Available online: https://www.istruzione.it/educazione_civica/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- MATTM. MIUR. Linee Guida Educazione Ambientale. 2014. Available online: https://www.mite.gov.it/sites/default/files/archivio/allegati/LINEE_GUIDA.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Salas-Zapata, W.A.; Rìos-Osorio, L.A.; Cardona-Arias, J.A. Knowledge, attitudes and Practice of Sustainability: Systematic Review 1990–2016. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2018, 20, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghorbani, S.; Jafari, S.E.M.; Sharifian, F. Learning to be: Teachers’ competences and practical solutions: A step towards sustainable development. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2018, 20, 20–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richter-Beuschel, L.; Bögeholz, S. Student teachers’ knowledge to enable problem-solving for sustainable development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benner, A.D.; Thornton, A.; Crosnoe, R. Children’s exposure to sustainability practices during the transition from preschool into school and their learning and socioemotional development. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2017, 21, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gough, A. Achieving “sustainability education” in primary schools as a result of the Victorian Science in Schools Research Project. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2004, 20, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N.; Boeve-de Pauw, J. The effectiveness of education for sustainable development revisited—A longitudinal study on secondary students’ action competence for sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 405–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Education for Sustainable Development Policy Dialogue: EFA ESD Dialogue: Educating for a Sustainable World, Paris 2008. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000178044 (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Maros, M.; Korenkova, M.; Fila, M.; Levicky, M.; Schoberova, M. Project-based learning and its effectiveness: Evidence from Slovakia. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulla, M.A. The effectiveness of the Project-Based Learning (PBL) approach as a way to engage students in learning. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaniotto, C.; Battistella, C.; Brunelli, L.; Ruscio, E.; Agodi, A.; Auxilia, F.; Baccolini, V.; Gelatti, U.; Odone, A.; Prato, R.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals and 2030 Agenda: Awareness, Knowledge and Attitudes in Nine Italian Universities, 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sustainability Literacy Test (SULITEST) of the Higher Education Sustainability Initiative (HESI). 2016. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/partnership/?p=9551 (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Ministero Dell’istruzione—Ministero dell’Università e Della Ricerca (MIUR). Focus “Principali dati Della Scuola—Avvio Anno Scolastico 2019/2020”. Available online: https://www.miur.gov.it/documents/20182/0/Principali+dati+della+scuola+-+avvio+anno+scolastico+2019-2020.pdf/5c4e6cc5-5df1-7bb1-2131-884daf008088?version=1.0&t=1570015597058 (accessed on 4 December 2021).

- The European Commission. Education and Training—Monitor 2019—Italy. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/education/files/document-library-docs/et-monitor-report-2019-italy_en.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Lazzarini, B.; Pérez-Foguet, A.; Boni, A. Key characteristics of academics promoting Sustainable Human Development within engineering studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ULSF (Association of University Leaders for a Sustainable Future) The Talloires Declaration—10 Point Action Plan. 1990. Available online: http://ulsf.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/TD.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Vare, P. A Rounder Sense of Purpose: Developing and Assessing Competences for Educators of Sustainable Development. Form@ re 2018, 18, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Polo, F.; Sánchez-Martín, J.; Corrales-Serrano, M.; Espejo-Antúnez, L. What Do University Students Know about Sustainable Development Goals? A Realistic Approach to the Reception of this UN Program Amongst the Youth Population. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leal Filho, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Misfud, M.; Àvila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeteiro, U.M.; Vargas, V.R.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flores, R.C. Representaciones sociales del medio ambiente. Perf. Educ. 2008, 30, 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zamora-Polo, F.; Sánchez-Martín, J. Teaching for a Better World. Sustainability and Sustainable Development Goals in the Construction of a Change-Maker University. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The European Commission. Education Policy Outlook—Italy. 2017. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/education/Education-Policy-Outlook-Country-Profile-Italy.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Boon, H. Beliefs and education for sustainability in rural and regional Australia. Educ. Rural. Aust. 2011, 21, 37–54. [Google Scholar]

| Question | Knowledge Level | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Limited | Fair | Good | Very Good | ||||||

| N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | |

| SDGs and 2030 Agenda | 25 | 6.0 | 70 | 16.8 | 129 | 31.0 | 157 | 37.6 | 36 | 8.6 |

| Ecological footprint | 23 | 5.5 | 55 | 13.2 | 106 | 25.4 | 189 | 45.3 | 44 | 10.6 |

| Greenhouse effect | 2 | 0.5 | 36 | 8.6 | 112 | 26.9 | 185 | 44.4 | 82 | 19.6 |

| Resilience | 13 | 3.1 | 66 | 15.8 | 116 | 27.8 | 168 | 40.3 | 54 | 12.9 |

| Social gradient | 114 | 27.4 | 123 | 29.5 | 99 | 23.7 | 76 | 18.2 | 5 | 1.2 |

| Determinants of health | 87 | 20.9 | 101 | 24.2 | 120 | 28.8 | 89 | 21.3 | 20 | 4.8 |

| Green Gross Domestic Product | 121 | 29.0 | 148 | 35.5 | 98 | 23.5 | 47 | 11.3 | 3 | 0.7 |

| Human Development Index (HDI) | 91 | 21.8 | 115 | 27.6 | 114 | 27.3 | 74 | 17.8 | 23 | 5.5 |

| Index of Sustainable Economic welfare (ISEW) | 102 | 24.5 | 139 | 33.3 | 87 | 20.9 | 76 | 18.2 | 13 | 3.1 |

| Equitable and sustainable well-being (BES) | 49 | 11.8 | 114 | 27.3 | 122 | 29.3 | 111 | 26.6 | 21 | 5.0 |

| Brundtland Report (1987) | 253 | 60.7 | 92 | 22.1 | 46 | 11.0 | 16 | 3.8 | 10 | 2.4 |

| Kyoto Protocol (1997) | 26 | 6.2 | 103 | 24.7 | 146 | 35.0 | 107 | 25.7 | 35 | 8.4 |

| Paris Agreement on climate change (2015) | 27 | 6.5 | 105 | 25.2 | 141 | 33.8 | 113 | 27.1 | 31 | 7.4 |

| Doughnut Economy | 231 | 55.4 | 113 | 27.1 | 47 | 11.3 | 23 | 5.5 | 3 | 0.7 |

| OVERALL | 1164 | 19.9 | 1380 | 23.6 | 1483 | 25.4 | 1431 | 24.5 | 380 | 6.5 |

| Question | Source of Information | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Knowledge about the Topic | Specific Training/ Event | Television | Newspapers/Magazines/Books | Internet | ||||||

| N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | |

| SDG and 2030 Agenda | 34 | 8.2 | 139 | 33.3 | 90 | 21.6 | 194 | 46.5 | 278 | 66.7 |

| Ecological footprint | 44 | 10.6 | 99 | 23.7 | 83 | 19.9 | 202 | 48.4 | 235 | 56.4 |

| Greenhouse effect | 6 | 1.4 | 92 | 22.1 | 153 | 36.7 | 295 | 70.7 | 250 | 60.0 |

| Resilience | 53 | 12.7 | 113 | 27.1 | 77 | 18.5 | 193 | 46.3 | 209 | 50.1 |

| Social gradient | 203 | 48.7 | 19 | 4.6 | 59 | 14.2 | 90 | 21.6 | 129 | 30.9 |

| Determinants of health | 151 | 36.2 | 49 | 11.8 | 82 | 19.7 | 128 | 30.7 | 153 | 36.7 |

| Green Gross Domestic Product | 198 | 47.5 | 21 | 5.0 | 64 | 15.4 | 100 | 24.0 | 127 | 30.5 |

| Human Development Index | 141 | 33.8 | 41 | 9.8 | 69 | 16.6 | 154 | 36.9 | 149 | 35.7 |

| Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW) | 162 | 38.9 | 53 | 12.7 | 50 | 12.0 | 127 | 30.5 | 162 | 38.9 |

| Equitable and sustainable well-being (BES) | 94 | 22.5 | 70 | 16.8 | 82 | 19.7 | 180 | 43.2 | 204 | 48.9 |

| Brundtland Report (1987) | 292 | 70.0 | 19 | 4.6 | 34 | 8.2 | 55 | 13.2 | 73 | 17.5 |

| Kyoto Protocol (1997) | 42 | 10.1 | 72 | 17.3 | 159 | 38.1 | 245 | 58.8 | 218 | 52.3 |

| Paris Agreement on climate change (2015) | 40 | 9.6 | 64 | 15.4 | 164 | 39.3 | 233 | 55.9 | 224 | 53.7 |

| Doughnut Economy | 292 | 70.0 | 17 | 4.1 | 35 | 8.4 | 51 | 12.2 | 80 | 19.2 |

| OVERALL | 1752 | 30.0 | 868 | 14.8 | 1201 | 20.6 | 2247 | 38.5 | 2491 | 42.7 |

| Question | Attitudes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I Do Not Think It Should Be Taught in School | It Should Be Taught in Designated Hours | It Could Be Taught in Lessons of the Subject I Teach, but for Personal Culture | It Could Be Taught in Lessons of the Subject I Teach, as Integral Part | |||||

| N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | |

| SDG and 2030 Agenda | 6 | 1.4 | 162 | 38.9 | 52 | 12.5 | 197 | 47.2 |

| Ecological footprint | 4 | 0.9 | 158 | 37.9 | 62 | 14.9 | 193 | 46.3 |

| Greenhouse effect | 8 | 2.0 | 166 | 39.8 | 58 | 13.8 | 185 | 44.4 |

| Resilience | 34 | 8.2 | 149 | 35.7 | 98 | 23.5 | 136 | 32.6 |

| Social gradient | 44 | 10.6 | 192 | 46.0 | 80 | 19.2 | 101 | 24.2 |

| Determinants of health | 25 | 6.0 | 198 | 47.5 | 69 | 16.5 | 125 | 30.0 |

| Green Gross Domestic Product | 42 | 10.1 | 205 | 49.2 | 64 | 15.3 | 106 | 25.4 |

| Human Development Index (HDI) | 35 | 8.4 | 180 | 43.2 | 61 | 14.6 | 141 | 33.8 |

| Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW) | 30 | 7.2 | 195 | 46.8 | 56 | 13.4 | 136 | 32.6 |

| Equitable and sustainable well-being (BES) | 21 | 5.0 | 182 | 43.6 | 62 | 14.9 | 152 | 36.5 |

| Brundtland Report (1987) | 73 | 17.5 | 206 | 49.4 | 67 | 16.1 | 71 | 17.0 |

| Kyoto Protocol (1997) | 32 | 7.7 | 172 | 41.2 | 65 | 15.6 | 148 | 35.5 |

| Paris Agreement on climate change (2015) | 22 | 5.3 | 174 | 41.7 | 70 | 16.8 | 151 | 36.2 |

| Doughnut Economy | 70 | 16.8 | 206 | 49.4 | 71 | 17.0 | 70 | 16.8 |

| OVERALL | 446 | 7.6 | 2545 | 43.6 | 935 | 16.0 | 1912 | 32.8 |

| Item | School Committment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Minimum | Moderate | Good | Very Good | ||||||

| N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | N. | % | |

| Sustainable food production and consumption | 23 | 5.5 | 98 | 23.5 | 121 | 29.0 | 130 | 31.2 | 45 | 10.8 |

| Recycling and waste reduction | 9 | 2.2 | 50 | 12.0 | 93 | 22.3 | 184 | 44.1 | 81 | 19.4 |

| Resilient infrastructures and sustainable industrialisation | 89 | 21.3 | 126 | 30.2 | 114 | 27.3 | 77 | 18.5 | 11 | 2.7 |

| Energy conservation and diffusion of renewable energy sources | 61 | 14.6 | 111 | 26.6 | 99 | 23.8 | 109 | 26.1 | 37 | 8.9 |

| Entrepreneurial skills and competences in labour market | 93 | 22.3 | 116 | 27.8 | 117 | 28.1 | 76 | 18.2 | 15 | 3.6 |

| Fight against inequalities, poverty and social exclusion | 24 | 5.8 | 59 | 14.1 | 96 | 23.0 | 167 | 40.1 | 71 | 17.0 |

| Circular economy and correct choice of assets | 48 | 11.5 | 113 | 27.1 | 132 | 31.6 | 102 | 24.5 | 22 | 5.3 |

| Building of participatory, inclusive and pacific societies | 49 | 11.8 | 88 | 21.1 | 102 | 24.5 | 120 | 28.8 | 58 | 13.80 |

| OVERALL | 396 | 11.9 | 761 | 22.8 | 874 | 26.2 | 965 | 28.9 | 340 | 10.2 |

| Knowledge | |||

| Variables | Coefficient | Std. Err | p |

| Does the school where you are currently teaching favour education for sustainability and integration of sustainability in the didactic programmes? | +9.3 | 3.1 | 0.003 |

| Previous attendance of specific non-academic courses on SDGs | +9.2 | 1.6 | <0.001 |

| Bachelor’s degree vs. high school diploma | +8.1 | 2.1 | <0.001 |

| School region: South&Islands vs. Nord | +6.3 | 1.7 | <0.001 |

| Active citizenship projects vs. frontal lessons | +5.2 | 1.8 | 0.004 |

| Workshops vs. classroom-taught lessons | +4.9 | 2.4 | 0.04 |

| Age (years) | +0.25 | 0.09 | 0.003 |

| School level: High school vs. Kindergarten | −4.1 | 1.8 | 0.02 |

| School Commitment | |||

| Variables | Coefficient | Std. Err | p |

| Does the school where you are currently teaching favour education for sustainability and integration of sustainability in the didactic programmes? | +27.3 | 3.7 | <0.001 |

| Workshops vs. classroom-taught lessons | +16.2 | 2.9 | <0.001 |

| Active citizenship projects vs. classroom-taught lessons | +11.5 | 2.3 | <0.001 |

| Other initiatives vs. classroom-taught lessons | +10.5 | 4.3 | 0.015 |

| Testimonials/experiences vs. classroom-taught lessons | +7.9 | 3.7 | 0.035 |

| Indipendent school vs. public school | +8.8 | 3.7 | 0.017 |

| Gender: male vs. female | +6.4 | 2.7 | 0.017 |

| School level: Lower secondary school vs. Kindergarten | +5.1 | 2.1 | 0.016 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smaniotto, C.; Brunelli, L.; Miotto, E.; Del Pin, M.; Ruscio, E.; Parpinel, M. Sustainable Development Goals and 2030 Agenda—Survey on Awareness, Knowledge and Attitudes of Italian Teachers of Public Mandatory Schools, 2021. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127469

Smaniotto C, Brunelli L, Miotto E, Del Pin M, Ruscio E, Parpinel M. Sustainable Development Goals and 2030 Agenda—Survey on Awareness, Knowledge and Attitudes of Italian Teachers of Public Mandatory Schools, 2021. Sustainability. 2022; 14(12):7469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127469

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmaniotto, Cecilia, Laura Brunelli, Edoardo Miotto, Massimo Del Pin, Edoardo Ruscio, and Maria Parpinel. 2022. "Sustainable Development Goals and 2030 Agenda—Survey on Awareness, Knowledge and Attitudes of Italian Teachers of Public Mandatory Schools, 2021" Sustainability 14, no. 12: 7469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127469

APA StyleSmaniotto, C., Brunelli, L., Miotto, E., Del Pin, M., Ruscio, E., & Parpinel, M. (2022). Sustainable Development Goals and 2030 Agenda—Survey on Awareness, Knowledge and Attitudes of Italian Teachers of Public Mandatory Schools, 2021. Sustainability, 14(12), 7469. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127469