Abstract

This study investigates whether investors react to disclosures of sustainable development. The study further examines if the legislative change has affected investors’ perception on sustainability disclosure via the corporate governance mechanism. With the recent legislative change in Korea, the gender quota may have negatively impacted corporate governance due to tokenism. In this study, we employ a natural experiment and event study with the 72 largest Korean firms listed in the stock market. Findings indicate that firms with female directors experience significant abnormal returns around event days, and that the firms meeting the minimal gender quota requirement indicate insignificant abnormal returns. This implies that firms with female directors provide better governance with diversity in the boardroom. However, the benefits from gender diversity become weak when tokenism is applied to them. The study makes several contributions to the governance and sustainability literature by providing additional evidence on tokenism. Findings have implications about the relationship between corporate governance and sustainable development for academia and practitioners.

1. Introduction

Gender diversity in the boardroom has been the center of debate in corporate governance in recent years. Prior studies and existing theories argue that gender diversity generally improves corporate governance. According to resource dependence theory, gender diversity on a board enhances the firm’s legitimacy, access to external sources, and communication with diverse opinions [1,2]. Empirical evidence shows that the presence of female directors enhances compliance with the social principles adopted by a firm [3]. Corporate governance also plays a vital role in the context of sustainability practices [4,5,6]. The authors in [7] discussed that firms utilize corporate governance mechanisms to engage more in sustainable development. However, in [7], the authors also found that the relationships between corporate social responsibility and firm-level variables are often misspecified or misled by omitted variables. Thus, this study aims to provide a new approach to examine issues with sustainable development goals. This study investigates whether investors react to disclosures of sustainable development. The study further examines if legislative changes in corporate governance affect the investors’ perception of sustainability disclosure.

The Korean government has mandated a board gender quota beginning in 2022. The gender quota law was passed in early 2020 and was supposed to be effective in July 2020, but exempted until July 2022. Many Korean firms started hiring female directors in March 2020, for which shareholder meetings first took place after the passing of the gender quota bill. Given that female directors on the board generally improve corporate governance [8], this study supports prior studies and evidence that firms with female directors provide value-relevant sustainability disclosures. However, tokenism predicts that female directors may be considered to be tokens when the firms only meet the minimal requirements to maintain compliance laws [9]. The legislative changes in Korea provide a natural experiment where this study is able to examine the effects of gender diversity requirements on corporate governance and eventually on the value relevance of sustainable development.

According to resource dependence theory, female directors are more sensitive to health and environmental concerns, and more engaged in social activities than men are [10,11]. Therefore, it is generally assumed that gender diversity enhances the engagement of sustainable activities via governance mechanisms. Although existing theories state that firms benefit from board diversity in their sustainable development, others claim that investors may view female directors as tokens when the firm meets only the minimal requirements in hiring the female directors by the law [12,13,14]. This is explained by “tokenism”, referring to a skewed imbalance of members in an organization where members of one group are dominant, while the other group is considered to be the tokens until the minority reaches a certain level in an organization [13,14]. So, the legislative change in Korea presents a unique opportunity to test tokenism regarding gender diversity.

We collected 101 sustainability reports (72 firms) for firms with total assets of more than KRW 2 trillion in 2020 and 2021 through the Repository of Korea’s Corporate Filings (electronic database for corporate filings). Firms holding more than KRW 2 trillion (equivalent to about USD 2 billion) will have the quota law enforced in coming years. We collected the disclosure dates and ran the event study to examine the value relevance of sustainability disclosure and the effects of the new gender quota law on such value relevance. Firms with female directors experience abnormal returns around event days [15,16,17]. This implies that firms with female directors provide better governance with diversity in the boardroom. Nonetheless, benefits from gender diversity become weak when tokenism is applied to them [9]. Cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) with a 3-day window show more robust evidence supporting the prediction.

Findings in this study contribute threefold to the corporate governance and sustainability literature. First, the evidence in this study is consistent with resource dependence theory. We confirm that firms benefit from corporate governance in their sustainable development [18]. Second, the study highlights the legislative change to examine the differential effect of corporate governance on the value relevance of sustainability reports [9]. Lastly, we provide a natural experiment and event study to tease out possible confounding effects on the results.

2. Prior Literature and Hypothesis Development

There are many studies examining the effects of governance on sustainability developments or vice versa. In particular, gender equality or inequality on boards has been the center of discussion in the context of corporate governance. However, empirical research is rarely conducted due to the limited setting of such experiments. With the recent legislative change in Korea, we posit the following research questions [19,20]: Do firms benefit from gender diversity for the value of sustainable development? If so, are there effects of legislative changes on the benefits from gender composition in boards?

Prior studies examined the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability in various settings. Although corporate governance measures are standardized in the literature, the definitions of corporate sustainability are described in the following terms: social responsibility, corporate sustainability, sustainability developments, etc. [21,22]. One stream of governance research focuses on the relationship between corporate governance and sustainability performance. The authors in [23] examined the relationship between corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance characteristics. They found that government ownership and audit committees positively impact the disclosure of corporate sustainability. This finding implies that good governance proxied by government ownership plays an important role in corporate sustainability reporting practices via governance mechanisms. The authors in [24] also support that good governance leads to better sustainability reporting. They found that governance variables such as board size, professionalism, and board designations have a positive influence on sustainability reporting. They argued that agency theory drives the positive relationship between them because agents expect managers to maximize the value of a firm. Other studies provide evidence on the reverse relation between corporate governance and sustainability reports. In [25], the authors investigated whether the quality of sustainability reports subsequently impacts corporate reputation. Assuming that the assurance of sustainability reports enhances the quality of the reports, the authors in [25] suggested that corporate reputation is driven by the quality of sustainability information. In [26], the authors investigated whether there were specific reasons for companies choosing to disclose sustainability information. They found that companies disclosing sustainability reports were motivated to enhance their corporate governance, particularly in the areas of reputation and legitimacy. The studies mentioned above generally found a positive relationship between governance and corporate sustainability reporting by focusing on the quantitative measure of corporate governance, namely, board size [27,28].

Another stream of the literature focuses on the qualitative measures of corporate governance, including board independence and diversity on the board. Early studies on diversity have claimed that companies benefit from diversity by meeting customer demand, enriching the understanding of the taste of marketplace, and improving the quality of products and services [29,30]. They generally paid attention to cultural diversity and its value. Board independence plays an essential role in governance because an independent director as a watchdog ensures that agents (managers) control the firms in the way desired by the principals. Therefore, it is assumed that independent directors lead to more and better corporate sustainability reporting by monitoring business activities [31]. In [32], the authors found that board diversity is positively associated with CSR performance. The authors in [33] also argued that gender diversity in the board of directors enhances CSR performance. Although there might be regional and industrial effects on the results, proponents of gender diversity argue that gender diversity adds values to a firm by leading to innovative thinking and signaling to investors about corporate governance [34]. In [34], the authors provided surveys with participants from multiple countries and industries to rule out the impacts of regions and industries. According to resource dependence theory, female directors are more sensitive to health and environmental concerns, and more engaged in social activities than men are [10,11]. Hence, it is an empirical question of whether gender diversity enforced by the government impacts sustainability reporting. As a result, we tested the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Firms with female directors are positively associated with the value of sustainable development disclosures.

Even though existing theories and prior evidence have asserted that firms benefit from board diversity in their performance and strategy, the authors in [35] suggested that the benefits from gender diversity may be threatened when certain conditions are met. In [35], the authors found that diversity may cause conflicts in decision making and impede achieving strategic changes. Others also claim that investors may view female directors as tokens when the firm meets only the minimal requirements of the law on hiring female directors [12]. This is explained by “tokenism”, referring to a skewed imbalance of members in an organization where members of one group are dominant, while members of the other are considered to be the tokens until the minority reaches a certain level (ex > 15%) in an organization [13,14]. Thus, in the setting where Korea mandates gender quota in the board of directors, we expect that the benefits from gender diversity may be offset by tokenism because investors may view female directors as tokens if the firms meet only the minimum or if the firms first hire a female director after the legislative process. In a similar experiment, the authors in [20] presented evidence that mandated gender diversity in the state of California negatively impacted the firm value, especially when there was a limited supply of female directors. Given the evidence of the prior literature and the first hypothesis [36,37], it is important to see if the benefits of board diversity are weakened by tokenism in this context. Accordingly, we posit the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Firms hiring female directors to meet the minimal requirements are not better in the value of sustainable development disclosures than firms without female directors are.

3. Research Design and Sample Selection

3.1. Legislative Change in Korea

The Democratic Party of Korea first proposed the gender quota bill on 1 October 2018. The bill requires firms of a specific total asset size to not hire board members of only one gender. With male dominance on the boards, this means that firms must hire at least one female director in their boards. The bill applies to public firms with assets worth more than KRW 2 trillion. As of 2022, more than 170 firms in the Korean stock market have been affected by this bill. As prior studies and existing theories suggest, gender diversity on boards is desired because it improves governance and consequently affects firm performance in various areas of business. The purpose of the bill is to mandate board diversity and thereby improve the governance of firms. The bill was passed in Congress in January 2020, and was enacted in July 2020. However, for the period of firm preparation, firms are exempted until July 2022. During the two years of preparation, nevertheless, the firms replaced their male directors with female directors when the incumbent directors’ tenure ended from shareholder meetings in 2020. In the Korean stock market, the fiscal years of most firms end in December, which means that their shareholder meetings must be conducted by the end of March every year. Therefore, March 2020 was officially the first season to hire female directors, and for them to be approved by shareholders under this legislative change. Table 1 describes the timeline of the legislative process of the mandatory gender quota.

Table 1.

Timeline of the legislative process for mandatory gender quota.

3.2. Sustainable Development Disclosure and Event Study

Sustainable development for firms is incorporated into the sustainability reports of the firms. Several firms regularly disclose their sustainability reports every year. Reports include contents of sustainable development (and their goals), the scope of the evaluation of such development, and quality assurance by external professionals. In Korea, about 100 sustainability reports are disclosed every year. They are usually disclosed around summer time because many Korean firms complete their fiscal year in December and their shareholder meetings in March. Thus, numerous firms disclose their sustainability reports during the nonpeak season from June to August, since such disclosures are still voluntary in practice.

The legislative change discussed in the prior section had real impacts on financial and nonfinancial reporting in early 2020. Although there is no legal enforcement until July 2022, it is generally assumed that composing the board of directors began in March 2020, when the firms had their first shareholder meetings since the passage of the bill. This timeline creates a natural experiment to test the investors’ perception (value relevance) on the sustainability reports disclosed by firms. Starting in March 2020, a number of firms began hiring a female director on their boards, and hiring female directors was a dominant issue of corporate governance. Thus, as we developed our hypotheses, we found that gender diversity influences the investors’ perception on sustainability reporting via the corporate governance mechanism.

We collected 101 sustainability reports (72 firms) for firms with total assets of more than KRW 2 trillion in 2020 and 2021 through the Repository of Korea’s Corporate Filings (electronic database for corporate filings). Appendix A presents the list of 72 firms disclosing sustainability reports. We collected the reports and their disclosure dates in order to examine the investors’ perception on the reports. Using the event study method [38], we investigated whether the disclosure events were valued by investors using three different samples. First, we estimated Equation (1) with equally weighted returns for the sample firms during the estimation period (−250 to −11 days).

where

Rjt = αj + βj Rmt + εjt

- Rit = return of firm i’s stock traded on day t;

- Rmt = return of the market’s stock traded on day t;

- αi = estimated individual firm constant;

- βi = estimated individual firm slope coefficient;

- εit = return residual for firm i on day t.

After we ran Equation (1), we estimated the coefficients on α and β using the following equation.

We calculated the abnormal returns during the testing period (−5 to +5) for individual firm i on each day (AR). In addition, we also measured the average abnormal returns for the portfolio on each day using the following equations AAR). Thus, AAR is the portfolio average of abnormal returns for 101 observations on each day. For example, the first column of Table 2 on Day −4 indicates 0.00158. This is the mean of abnormal returns on Day −4 for 101 observations. The subsequent columns are subsets of the overall sample with 101 observations. Accordingly, the second column presents the means of abnormal returns on each day for group without female directors (obs = 49).

Table 2.

Individual day returns.

Then, we also calculated the cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) for specific windows using the following equations.

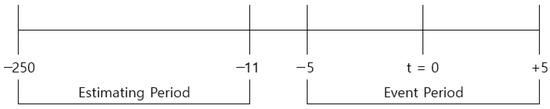

We partitioned our sample into subgroups and calculated the CAR for each group. Figure 1 presents the specific timeline for the estimation and testing periods to estimate the above equations. Accordingly, the first row of Table 3 indicates the cumulative abnormal returns of 3-day window between Days −1 and +1 for each group. For example, the third column in the first row in Table 3 presents 0.00448, which indicates the average CAR for the group with female directors (obs = 52).

Figure 1.

Estimating and event periods.

Table 3.

Cumulative abnormal returns for windows and groups.

4. Empirical Results

Abnormal Returns on Event Dates

To test H1, we estimated the abnormal returns on pre- and postevent dates. Assuming that the expected returns were zero (0) without events, significant abnormal returns on event dates indicate that the investors reacted to the events. Thus, we interpreted this as a value relevance of information about sustainable development. Table 2 displays the abnormal returns on the event window between 5 pre-event days and 5 postevent days. We partitioned our sample into four different groups: (1) firms without female directors (female = 0), (2) firms with female directors (female = 1), (3) firms with female directors during the period of the legislative change (first = 1), and (4) firms with female directors even before the legislative change (first = 0). Group 1 (female = 0) represents firms with relatively poor governance because the firms have not hired any female directors even after the legislative changes had been completed. Group 2 (female = 1) includes firms with female directors before and after the legislative changes. Thus, we created subgroups within Group 2, namely, Groups 3 and 4. Group 3 consists of firms first hiring female directors during the legislative changes.

Conversely, Group 4 includes firms with female directors before the legislative changes. Thus, Group 3 represents firms considered to be tokens following tokenism because they meet only the minimal requirements of the law since the legislative changes. On the other hand, Group 4 had the best governance out of the four groups because they hired female directors well before the legal requirements. As a result, the difference between Groups 3 and 4 provides meaningful evidence in this study.

On the basis of prior studies and existing theories, firms should benefit from good governance on their boards. The disclosure of sustainability development is perceived to be value-relevant by investors if there are significant returns on event dates. We expect that firms with female directors (female = 1) provide better governance than that of firms without female directors; thus, firms with female directors had significantly positive returns on event dates. Table 2 investigates whether female directors serving on the board affect the value relevance of the disclosure of sustainability reports. The table provides the returns of individual days at pre- and postevent dates (disclosure dates). We carefully collected the information of firms disclosing sustainability reports by teasing out other events (i.e., earnings announcements) or confounding effects (conference calls etc.). The first column presents the daily abnormal returns of all firms in the sample. Days −2 and +1 showed significant abnormal returns, but they were in opposite directions (negative). Although we expected positive returns around the event date, we interpreted our results as being affected by Group 2 or 3, where poor governance was expected. Only Group 4 presented a significant positive abnormal return on an event day (Day 0), and the magnitude of return was relatively high and significant at a 1% level. This implies that firms with incumbent female directors provide better governance, and investors perceive them similarly. The first group, on the other hand, indicates negative and significant abnormal returns around event days (Days 0 and +1). It also confirms that firms without female directors may provide poor governance, and investors may penalize them when the sustainability reports are disclosed. In sum, abnormal daily returns around the event days provide only preliminary evidence that investors generally view disclosures as value-relevant. Nevertheless, investors may perceive them in different ways. The following section provides further evidence on the cumulative abnormal returns around event days.

Table 3 presents the cumulative abnormal returns for each group of interest. In the event study, we generally focused on the 3-day and 2-day windows of pre- and post- event period. The 3-day CAR for firms without female directors (female = 0) was −0.00813 and statistically significant. This implies that investors viewed the disclosure of sustainability reports negatively when the board of directors did not include any female directors. The CARs for other windows of Group 1 also indicate significant negative signs, which provides consistent results with the group of the possibility of poor governance. CARs for firms with female directors presented positive signs for most windows, but they are not yet statistically significant. This is consistent with the aforementioned predictions that, in the subgroup first hiring female directors due to legislative changes, the directors are considered to be tokens [9]. Therefore, investors may negatively view disclosures by this group. Nonetheless, firms with continuing female directors experience higher cumulative abnormal returns than those of most other groups. This is not an unexpected result, since existing theories support the notion that firms should benefit from sustainable development, and female directors may enhance this benefit as a proxy for good governance.

Table 4 provides the hypothesis tests using one-tailed Kruskal–Wallis test [41]. The Kruskal–Wallis test is a nonparametric test comparing two or more samples. It is similar to one-way analysis of variance in parametric tests. Since most event studies do not assume a normal distribution of the residuals, the test is often used to test whether the abnormal returns of one group are greater than those of the other group [42]. The table presents the chi-squared test and its applicable p-value in each column. The first column compares two groups, Female = 1 and Female = 0, where we investigated the effect of female directors on CARs via the governance mechanism. Statistics indicate significant CARs around event days, especially for Day 0 and the 3-day window (−1, +1). In particular, the first column on the second row presents a chi squared of 5.3375 with a p-value of 0.0209. This means that the average CARs for the group with female directors (Female = 1) were greater than those for the group without female directors (Female = 0), and the difference between the two (Female = 1 > Female = 0) was statistically significant at the 5% level. This is consistent with our prediction that firms with female directors deliver better governance. Thus, investors positively react to the sustainability development disclosed by the firms. The second column compares two groups within the female-director group. It provides evidence that firms with continuing female directors report higher CARs on disclosure dates than those of firms with female directors first hired during the legislative changes. This provides evidence for our second hypothesis and supports the existing theory of tokenism.

Table 4.

Kruskal–Wallis test to compare groups.

Are firms with female directors first hired during the legislative changes (considered to be tokens) better than firms without female directors? The third column of Table 4 presents statistics to test if firms with female directors first hired during the legislative changes reported higher CARs on disclosure dates than those of firms without female directors. All windows in the third column indicate nonsignificant statistics. Therefore, the results confirm that even firms with female directors are not better off in their governance if they hire female directors to meet the minimal requirements by the law. This result is consistent with the existing theory of tokenism.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

With the increasing importance of sustainability, a number of scholars and practitioners are paying considerable attention to sustainability development [6]. Sustainability reports encompass the context of sustainability development, and investors evaluate these contents. Furthermore, corporate governance plays an essential role in sustainable development [4,43]. Thus, prior studies and existing theories generally support that corporate governance affects the practice of sustainable development in various aspects [29]. With the legislative change in Korea, it is an excellent opportunity to construct a natural experiment on the effect of corporate governance change on investors’ perception of sustainable development. This study investigates whether investors react to disclosures of sustainable development. The study further examines if an environmental change in corporate governance affects the investors’ perception of sustainability disclosure.

Using a natural experiment opportunity in Korea, this is, to the best of our knowledge, the first empirical study to examine the benefits of disclosure for sustainability information, and the effect of external shocks on corporate governance. We found that firms with female directors experience abnormal returns around event days. This implies that firms with female directors provide better governance with diversity in the boardroom. Nonetheless, the benefits from gender diversity become weak when tokenism is applies to them [9]. Cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) with a 3-day window show even more robust evidence supporting the prediction.

Given that female directors on the board generally improve corporate governance [8,44,45], this study supports prior studies and evidence. However, tokenism predicts that female directors may be considered to be tokens when firms only meet the minimal requirements by compliance laws [9]. The findings in this study are consistent with predictions in prior studies and theories. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate whether mandated diversity in the boardroom improves corporate governance, as the legislative actions intended. Thus, the study provides meaningful insights into the literature of corporate governance and sustainable development.

This study also provides some implications to practitioners and academia. For practitioners, it is essential to integrate gender diversity in the boardroom, but gender diversity should simultaneously work in the projected way of improving corporate governance. Even if prior evidence and some theories suggest that having a female director in the boardroom positively impacts corporations in various aspects, such as performance and governance, it may not be the case when we mandate gender diversity in the boardroom by law. It is particularly important for practitioners and legislators to consider tokenism, which can be applied to these phenomena. The current study also delivers critical implications for academia. As prior studies and evidence presented mixed results on research regarding gender diversity, our findings confirmed that gender diversity does not always work positively for corporations. The authors in [20] and authors in other studies demonstrated that gender diversity may not be the best practice when it meets some conditions and is mandated by the law. It is also possible that research settings in prior studies were affected by omitted variables [45]. The current study supports the existing theory of tokenism, and future studies should consider different contexts of sustainable business when conducting their research.

This study contributes threefold to the corporate governance and sustainability literature. First, the evidence in this study is consistent with resource dependence theory suggesting that firms benefit from corporate governance [18]. Second, the study highlights the legislative change to examine the differential effect of corporate governance on the value relevance of sustainability reports [9,46]. Lastly, we provided a natural experiment and event study to tease out any confounding effects on the results.

Even if this study has meaningfully contributed to the literature, we offer some suggestions for future research. The study used a small sample of events with which generalization may be hindered. Due to the nature of voluntary disclosures, sustainability reports are only disclosed by large firms. Thus, why firms disclose sustainability reports and how the reports affect various aspects of the firms’ business are open questions. Future research should examine these unresolved questions.

Author Contributions

W.-K.L. (first author) collected the data and conducted the statistical analysis. C.-K.P. (corresponding author) developed the research ideas and research design. Both authors contributed to the writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are publicly available with the sources mentioned in the text.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dongguk University and Dongguk Business School for their generous research support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. List of Companies in the Sample

| No. | Company Name | No. | Company Name |

| 1 | Doosan Co., Ltd. | 37 | Samsung Life Insurance Co., Ltd. |

| 2 | SK Hynix Inc. | 38 | KT & G Corporation |

| 3 | Hyundai Engineering & Construction Co., Ltd. | 39 | Doosan Enerbility Co., Ltd. |

| 4 | Hanwha Corporation | 40 | LG Display Co., Ltd. |

| 5 | SK Networks Co., Ltd. | 41 | SK Inc. |

| 6 | Hanwha Investment & Securities Co., Ltd. | 42 | Naver Corporation |

| 7 | Posco Chemical Co., Ltd. | 43 | Kakao Corporation |

| 8 | Lotte Fine Chemical Co., Ltd. | 44 | Korea Gas Corporation |

| 9 | Hyundai Steel Co., Ltd. | 45 | Ncsoft Corporation |

| 10 | Hansol Holdings Co., Ltd. | 46 | Hyundai Doosan Infracore Co., Ltd. |

| 11 | Sebang Co., Ltd. | 47 | Posco International |

| 12 | Lotte Corporation | 48 | LG Household & Health Care Co., Ltd. |

| 13 | Lotte Chilsung Beverage Co., Ltd. | 49 | LG Chem Co., Ltd. |

| 14 | Posco Holdings Inc. | 50 | Shinhan Financial Group |

| 15 | Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. | 51 | Hyundai Rotem Co., Ltd. |

| 16 | Nh Investment & Securities Co., Ltd. | 52 | LG Electronics Inc. |

| 17 | Samsung Electro-Mechanics Co., Ltd. | 53 | Lotte Himart Co., Ltd. |

| 18 | Hanssem Co., Ltd. | 54 | Mirae Asset Life Insurance Co., Ltd. |

| 19 | Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering Co., Ltd. | 55 | Hyundai Glovis Co., Ltd. |

| 20 | Hanwha Solutions Corporation | 56 | Hana Financial Group |

| 21 | Oci Co., Ltd. | 57 | Hanwha Life Insurance Co., Ltd. |

| 22 | Hyundai Mipo Dockyard Co., Ltd. | 58 | SK Innovation Co., Ltd. |

| 23 | S-Oil Corporation | 59 | KB Financial Group Inc. |

| 24 | LG Innotek Co., Ltd. | 60 | Kolon Industries Inc. |

| 25 | Lotte Chemical Corporation | 61 | BNK Financial Group |

| 26 | Hyundai Wia Co., Ltd. | 62 | DGB Financial Group |

| 27 | SKC Co., Ltd. | 63 | JB Financial Group |

| 28 | Hanwha Aerospace Co., Ltd. | 64 | Mando Corporation |

| 29 | Halla Corporation | 65 | Doosan Bobcat Inc. |

| 30 | Samsung Securities Co., Ltd. | 66 | Hyundai Electric & Energy Systems Co., Ltd. |

| 31 | Samsung SDS Co., Ltd. | 67 | Hyundai Construction Equipment Co., Ltd. |

| 32 | SK Gas Co., Ltd. | 68 | Hanwha Systems Co., Ltd. |

| 33 | Coway Co., Ltd. | 69 | Hyosung Advanced Materials Corporation |

| 34 | Industrial Bank of Korea | 70 | Hyundai Autoever Corporation |

| 35 | Kt Corporation | 71 | Woori Financial Group |

| 36 | LG Uplus Corporation | 72 | Hyundai Energy Solutions Co., Ltd. |

References

- Gao, H.; Lin, Y.; Ma, Y. Sex discrimination and female top managers: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Stanford Business Books; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Isidro, H.; Sobral, M. The effects of women on corporate boards on firm value, financial performance, and ethical and social compliance. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crifo, P.; Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Mottis, N. Corporate Governance as a Key Driver of Corporate Sustainability in France: The Role of Board Members and Investor Relations. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 1127–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Caracuel, J.; Guerrero-Villegas, J. How Corporate Social Responsibility Helps MNEs to Improve their Reputation. The Moderating Effects of Geographical Diversification and Operating in Developing Regions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Villegas, J.; Sierra-Garcia, L.; Palacios-Florencio, B. The role of sustainable development and innovation on firm performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1350–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Correlation or misspecifcation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.; Minguez-Vera, A. Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm financial performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 83, 435–451. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, R. Men and Women of the Corporation; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Salancik, G.; Pfeffer, J. A Social Information Processing Approach to Job Attitudes and Task Design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1978, 23, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.; Huse, M. The Contribution of Women on Boards of Directors: Going beyond the Surface. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2010, 18, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rixom, J.; Jackson, M.; Rixom, B. Mandating Diversity on the Board of Directors: Do Investors Feel That Gender Quotas Result in Tokenism or Added Value for Firms? J. Bus. Ethics 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, J.; Perez, A. Tokenism. In V. Sociology of Work: An Encyclopaedia; Smith, Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 883–884. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, L. Tokenism and Women in the Workplace: The Limits of Gender-Neutral Theory. Soc. Probl. 1988, 35, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosan, C. Disclosure Level and the Cost of Equity Capital. Account. Rev. 1997, 72, 323–349. [Google Scholar]

- Botosan, C.; Plumlee, M. A re-examination of disclosure level and the expected cost of equity capital. J. Account. Res. 2002, 40, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, A.; Taylor, D.; Ahmed, K. The value relevance of intellectual capital disclosures. J. Intellect. Cap. 2011, 12, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keasey, K.; Thompson, S.; Wright, M. Corporate governance, economic, management, and financial issues. Manag. Audit. J. 1998, 13, 390–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. KPMG International Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting. 2013. Available online: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2013/12/corporate-responsibility-reporting-survey-2013.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Greene, D.; Intintoli, V.; Kahle, K. Do board gender quotas affect firm value? Evidence from California Senate Bill No. 826. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 60, 101526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crifo, P.; Forget, V. The economics of corporate social responsibility: A frm level perspective survey. J. Econ. Surv. 2015, 29, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, R.; Zainuddin, Y.; Haron, H. The relationship between corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance characteristics in Malaysian public listed companies. Soc. Responsib. J. 2009, 5, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janggu, T.; Darus, F.; Zain, M.; Sawani, Y. Does Good Corporate Governance Lead to Better Sustainability Reporting? An Analysis Using Structural Equation Modeling. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 145, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clarke, J.; Gibson-Sweet, M. The use of corporate social disclosures in the management of reputation and legitimacy: A cross sectoral analysis of UK Top 100 Companies. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 1999, 8, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, T.; Beale, R. Developing Competency to Manage Diversity: Reading, Cases, and Activities; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dass, N.; Kini, O.; Nanda, V.; Onal, B.; Wang, J. Board expertise: Do directors from related industries help bridge the information gap? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2014, 27, 1533–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcker, D.; Richardson, S.; Tuna, I. Corporate governance, accounting outcomes, and organizational performance. Account. Rev. 2007, 82, 963–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, E. The Diversity Scorecard; Elsevier: Burlington, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Herring, C. Does diversity pay? Race, Gender, and the Business Case for Diversity. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 74, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jizi, M.; Salama, A.; Dixon, R.; Stratling, R. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: Evidence from the US Banking Sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harjoto, M.; Laksmana, I.; Lee, R. Board Diversity and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 641–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beji, R.; Yousfi, O.; Loukil, N.; Omri, A. Board Diversity and Corporate Social Responsibility: Empirical Evidence from France. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 173, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, S.; Wu, D.; Zhang, L. When Gender Diversity Makes Firms More Productive. Harvard Business Review, 11 February 2019. Available online: https://www.agec.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2019-HBR-research-when-gender-diversity-makes-firms-more-productive-hbr2019.pdf(accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Triana, M.; Miller, T.; Trzebiatowski, T. The Double-Edged nature of board gender diversity: Diversity, firm performance, and the power of women directors as predictors of strategic change. Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 609–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Torres, F.; Bustamante-Ubilla, M.; Santander-Ramirez, V.; Severino-Gonzalez, P. Diversity and governance: Is there really progress? Sustainability 2022, 14, 5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghuslan, M.; Jaffar, R.; Saleh, N.; Yaacob, M. Corporate governance and corporate reputation: The role of environmental and social reporting quality. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.; Lo, A.; MacKinlay, C.; Whitelaw, R. The Econometrics of Financial Markets. Macroecon. Dyn. 1998, 2, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.; French, K. The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns. J. Financ. 1992, 47, 427–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcoxon, F. Individual Comparisons by Ranking Methods. Biom. Bull. 1945, 1, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.; Wallis, W. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobisova, A.; Senova, A.; Izarikova, G.; Krutakova, I. Proposal of a methodology for assessing financial risks and investment development for sustainability of enterprises in Slovakia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cofey, B. Board composition and corporate philanthropy. J. Bus. Ethics 1992, 11, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirole, J. The Theory of Corporate Finance; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, Y.; Kang, S.; Zhu, Z. Gender Stereotyping by Location, Female Director Appointments and Financial Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisman-Razin, M.; Saguy, T. Reactions to tokenism: The role of individual characteristics in shaping responses to token decisions. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 46, 716–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).