How Collectivism Affects Organic Food Purchase Intention and Behavior: A Study with Norwegian and Portuguese Young Consumers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

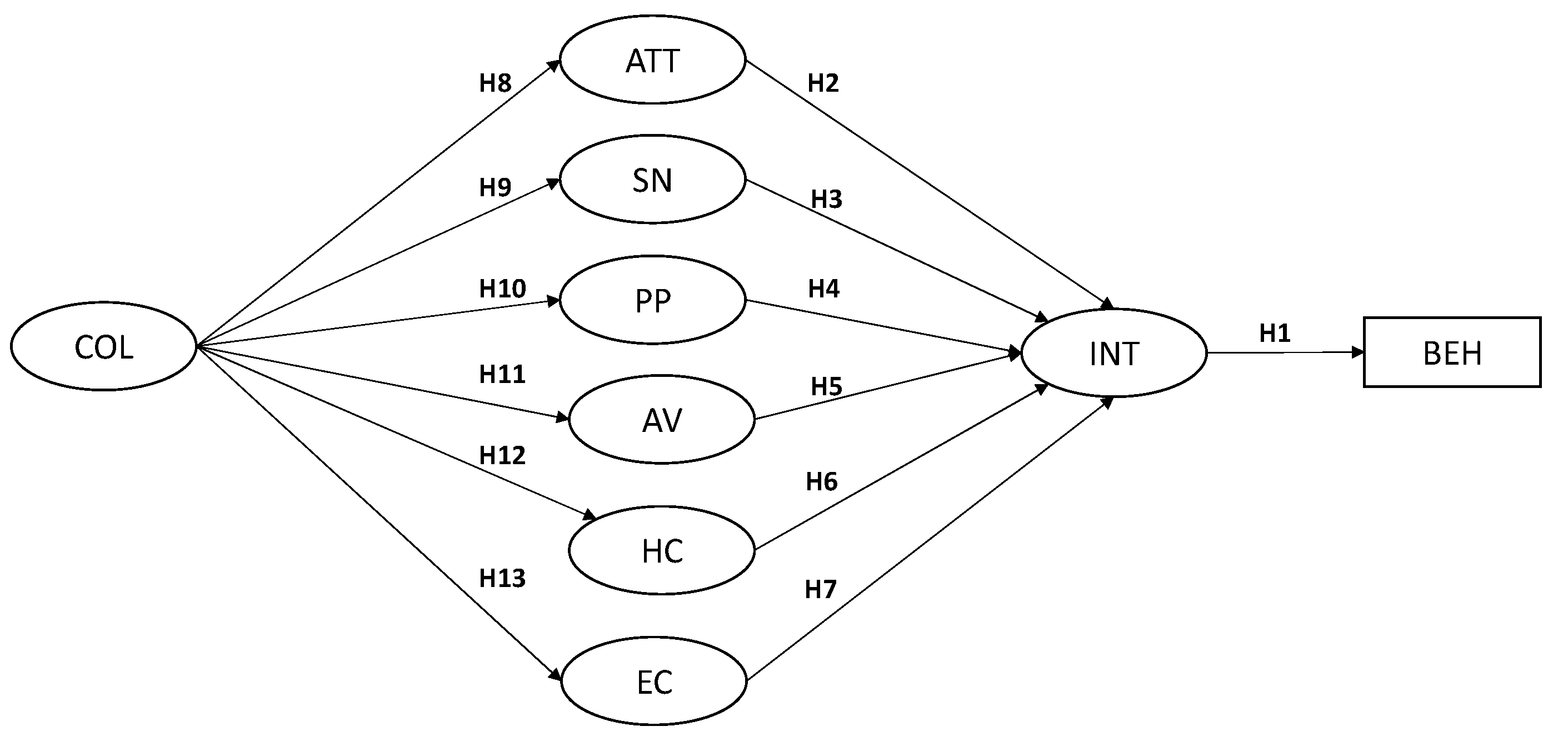

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. From Purchase Intentions to Behavior

2.2. Main Cognitive Determinants of Purchase Intentions

2.3. The Role of Health Consciousness and Environmental Concerns on Organic Food Purchase Intention

2.4. The Integration of Cultural Dimensions: Collectivism

3. Method

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias

4.2. Descriptive Analysis, Validity Indicators, and Goodness of Fit

4.3. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

4.4. Evaluation of Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

4.4.1. Test of Hypotheses

4.4.2. Comparison between Portugal and Norway

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

6.2. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items 1 | Adapted from |

|---|---|---|

| Collectivism | COL1 Individuals should sacrifice self-interest for the group. COL2 Individuals should stick with the group even through difficulties. COL3 Group welfare is more important than individual rewards. COL4 Group success is more important than individual success. COL5 Individuals should only pursue their goals after considering the welfare of the group. COL6 Group loyalty should be encouraged even if individual goals suffer. | Yoo et al. [77] |

| Health consciousness | HC1 I choose food carefully to ensure good health. HC2 I think of myself as a health-conscious consumer. HC3 I often think about health issues. | Tarkiainen and Sundqvist [9] |

| Environmental concern | EC1 Humans are severely abusing the environment. EC2 Humans must maintain the balance with nature in order to survive. EC3 Human interferences with nature often produce disastrous consequences. | Yadav and Pathak [11] |

| Attitude | ATT1 Buying organic foods is a good idea. ATT2 Buying organic foods is a wise choice. ATT3 I like the idea of buying organic foods. ATT4 Buying organic foods would be pleasant. | Yadav and Pathak [11] |

| Subjective norm | SN1 People who are important to me think that I should purchase organic foods. SN2 People who are important to me would want me to purchase organic foods. SN3 People whose opinions I value prefer that I purchase organic foods. SN4 My friends’ positive opinion influences me to purchase organic foods. | Paul et al. [78] |

| Perceived price | PP1 Organic foods are expensive. 3 PP2 The price of organic foods is in accordance with its benefits. PP3 The price for organic foods is fair. 2 | Singh and Verma [7] |

| Availability | AV1 Organic foods are always sufficiently available. AV2 It is easy to find organic foods. 2 AV3 It is easy to have access to organic foods. 2 | Tarkiainen and Sundqvist [9] |

| Purchase intention | INT1 I intend to buy organic products in the near future. INT2 I plan to buy organic foods in the future. INT3 I will make an effort to buy organic foods in the future. | Lee et al. [79] |

| Behavior | BEH How many times have you bought organic food in the last month? | Developed for this study |

References

- IFOAM. IFOAM EU Annual Report 2019; IFOAM: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Renub Research. Organic Food and Beverage Market. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5459135/organic-food-and-beverage-market-global-forecast (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Fleșeriu, C.; Cosma, S.A.; Bocăneț, V. Values and Planned Behaviour of the Romanian Organic Food Consumer. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dorce, L.C.; da Silva, M.C.; Mauad, J.R.C.; Domingues, C.H.D.F.; Borges, J.A.R. Extending the theory of planned behavior to understand consumer purchase behavior for organic vegetables in Brazil: The role of perceived health benefits, perceived sustainability benefits and perceived price. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 91, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikiene, G.; Mandravickaitė, J.; Bernatonienė, J. Theory of planned behavior approach to understand the green purchasing behavior in the EU: A cross-cultural study. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 125, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleki, R.; Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J. What drives Malaysian consumers’ organic food purchase intention? The role of moral norm, self-identity, environmental concern and price consciousness. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2019, 9, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Verma, P. Factors influencing Indian consumers’ actual buying behaviour towards organic food products. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, P.; Tarafder, T.; Pearson, D.; Henryks, J. Intention-behaviour gap and perceived behavioural control-behaviour gap in theory of planned behaviour: Moderating roles of communication, satisfaction and trust in organic food consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 81, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkiainen, A.; Sundqvist, S. Subjective norms, attitudes and intentions of Finnish consumers in buying organic food. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Tran, A.T.; Nguyen, N.T. Organic Food Consumption among Households in Hanoi: Importance of Situational Factors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Intention to purchase organic food among young consumers: Evidences from a developing nation. Appetite 2016, 96, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalco, A.; Noventa, S.; Sartori, R.; Ceschi, A. Predicting organic food consumption: A meta-analytic structural equation model based on the theory of planned behavior. Appetite 2017, 112, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.F.; Barbosa, B.; Cunha, H.; Oliveira, Z. Exploring the Antecedents of Organic Food Purchase Intention: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: Green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food: A review and research agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooij, M.; Hofstede, G. Cross-cultural consumer behavior: A review of research findings. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2011, 23, 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Boobalan, K.; Nawaz, N.; Harindranath, R.M.; Gajenderan, V. Influence of Altruistic Motives on Organic Food Purchase: Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, M.I.; Sarwar, H.; Ahmed, R. “A healthy outside starts from the inside”: A matter of sustainable consumption behavior in Italy and Pakistan. Bus. Ethic-Environ. Responsib. 2021, 30, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paço, A.; Alves, H.; Shiel, C.; Filho, W.L. A multi-country level analysis of the environmental attitudes and behaviours among young consumers. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2013, 56, 1532–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sreen, N.; Purbey, S.; Sadarangani, P. Impact of culture, behavior and gender on green purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Norway. Available online: http://data.oecd.org/norway.htm (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- OECD. Portugal. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/portugal.htm (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- Boobalan, K.; Nachimuthu, G.S. Organic consumerism: A comparison between India and the USA. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Attitudes of Europeans towards the Environment; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, X.; Ploeger, A. Explaining Chinese Consumers’ Green Food Purchase Intentions during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. Foods 2021, 10, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Tan, B.; Lau, T. Antecedents of Consumers’ Purchase Intention towards Organic Food: Integration of Theory of Planned Behavior and Protection Motivation Theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Wang, M.; Gong, S. Understanding the Antecedents of Organic Food Purchases: The Important Roles of Beliefs, Subjective Norms, and Identity Expressiveness. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le, M.H.; Nguyen, P.M. Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Norm Activation Model to Investigate Organic Food Purchase Intention: Evidence from Vietnam. Sustainability 2022, 14, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Azjen, I. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Leyva-Hernández, S.N.; Toledo-López, A.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. Purchase Intention for Organic Food Products in Mexico: The Mediation of Consumer Desire. Foods 2021, 10, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, N.; Nguyen, B.K.; Greenland, S. Sustainable Food Consumption: Investigating Organic Meat Purchase Intention by Vietnamese Consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Li, C.; Khan, A.; Qalati, S.A.; Naz, S.; Rana, F. Purchase intention toward organic food among young consumers using theory of planned behavior: Role of environmental concerns and environmental awareness. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 796–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Huque, S.M.R.; Hafeez, M.H.; Shariff, M.N.M. The role of subjective norms in theory of planned behavior in the context of organic food consumption. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1561–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavite, H.J.; Mankeb, P.; Suwanmaneepong, S. Community enterprise consumers’ intention to purchase organic rice in Thailand: The moderating role of product traceability knowledge. Br. Food J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenidou, I.E.; Stavrianea, A.; Bara, E.-Z. Generational Differences toward Organic Food Behavior: Insights from Five Generational Cohorts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hansmann, R.; Baur, I.; Binder, C.R. Increasing organic food consumption: An integrating model of drivers and barriers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 123058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Wang, X.; Nasiri, A.; Ayyub, S. Determinant factors influencing organic food purchase intention and the moderating role of awareness: A comparative analysis. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 63, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanti, R.K.; Burns, A.C. The Antecedents of Preventive Health Care Behavior: An Empirical Study. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1998, 26, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, S. Role of consumer health consciousness, food safety & attitude on organic food purchase in emerging market: A serial mediation model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, F.; Madureira, T.; Veiga, J. The Organic Food Choice Pattern: Are Organic Consumers Becoming More Alike? Foods 2021, 10, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska-Solis, J.; Barska, A. Exploring the Preferences of Consumers’ Organic Products in Aspects of Sustainable Consumption: The Case of the Polish Consumer. Agriculture 2021, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.M.; Phan, T.H.; Nguyen, H.L.; Dang, T.K.T.; Nguyen, N.D. Antecedents of Purchase Intention toward Organic Food in an Asian Emerging Market: A Study of Urban Vietnamese Consumers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Pham, T.L.; Dang, V.T. Environmental Consciousness and Organic Food Purchase Intention: A Moderated Mediation Model of Perceived Food Quality and Price Sensitivity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hofstede, G. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGrawHill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beugelsdijk, S.; Kostova, T.; Roth, K. An overview of Hofstede-inspired country-level culture research in international business since 2006. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2017, 48, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cho, Y.-N.; Thyroff, A.; Rapert, M.I.; Park, S.-Y.; Lee, H.J. To be or not to be green: Exploring individualism and collectivism as antecedents of environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. The many dimensions of culture. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2004, 18, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Luchs, M.G.; Miller, R.A. Consumer responsibility for sustainable consumption. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Consumption; Reisch, L., Thøgersen, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 254–267. [Google Scholar]

- de Morais, L.H.L.; Pinto, D.C.; Cruz-Jesus, F. Circular economy engagement: Altruism, status, and cultural orientation as drivers for sustainable consumption. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-T. Consumer characteristics and social influence factors on green purchasing intentions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2014, 32, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareklas, I.; Carlson, J.R.; Muehling, D.D. “I Eat Organic for My Benefit and Yours”: Egoistic and Altruistic Considerations for Purchasing Organic Food and Their Implications for Advertising Strategists. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Shrum, L. The recycling of solid wastes: Personal values, value orientations, and attitudes about recycling as antecedents of recycling behavior. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, J.B.; Verma, J. Structure of collectivism. In Growth and Progress in Cross-Cultural Psychology; Kağitçibaşi, Ç., Ed.; Swets North America: Berwyn, IL, USA, 1987; pp. 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J.; Chadee, D.; Tikoo, S. Culture, product type, and price influences on consumer purchase intention to buy personalized products online. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samarasinghe, R. The influence of cultural values and environmental attitudes on green consumer behaviour. J. Behav. Sci. 2012, 7, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of green purchase behavior: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and PCE. In Advances in Consumer Research; Menon, G., Rao, A.R., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Duluth, MN, USA, 2005; Volume 32, pp. 592–599. [Google Scholar]

- Arısal, I.; Atalar, T. The Exploring Relationships between Environmental Concern, Collectivism and Ecological Purchase Intention. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 235, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Understanding green purchase: The influence of collectivism, personal values and environmental attitudes, and the moderating effect of perceived consumer effectiveness. Seoul J. Bus. 2011, 17, 66–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Andover, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Banville, D.; Desrosiers, P.; Genet-Volet, Y. Translating Questionnaires and Inventories Using a Cross-Cultural Translation Technique. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2000, 19, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melović, B.; Dabić, M.; Rogić, S.; Đurišić, V.; Prorok, V. Food for thought: Identifying the influential factors that affect consumption of organic produce in today’s youth. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1130–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, I.; Phau, I. Attitudes towards environmentally friendly products: The influence of ecoliteracy, interpersonal influence and value orientation. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2011, 29, 452–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.H.; Nguyen, T.N.; Phan, T.T.H.; Nguyen, N.T. Evaluating the purchase behaviour of organic food by young consumers in an emerging market economy. J. Strat. Mark. 2019, 27, 540–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, P.D. Multiple imputation for missing data—A cautionary tale. Sociol. Methods Res. 2000, 28, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Zagata, L. Consumers’ beliefs and behavioural intentions towards organic food. Evidence from the Czech Republic. Appetite 2012, 59, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokthi, E.; Thoma, L.; Saary, R.; Kelemen-Erdos, A. Disconfirmation of Taste as a Measure of Trust in Brands: An Experimental Study on Mineral Water. Foods 2022, 11, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N.; Lenartowicz, T. Measuring Hofstede’s five dimensions of cultural values at the individual level: Development and validation of CVSCALE. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2011, 23, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hsu, L.-T.; Han, H.; Kim, Y. Understanding how consumers view green hotels: How a hotel’s green image can influence behavioural intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants’ Characteristics | Total Sample | Norway | Portugal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Age | 18–21 | 412 | 45.2 | 197 | 42.0 | 215 | 48.0 |

| 22–26 | 424 | 46.3 | 235 | 50.2 | 189 | 42.2 | |

| 27–30 | 80 | 8.5 | 36 | 7.8 | 44 | 9.8 | |

| Gender | Female | 630 | 68.8 | 309 | 66.0 | 321 | 71.7 |

| Male | 286 | 31.2 | 159 | 44.0 | 127 | 28.3 | |

| Highest Education Level Completed | High school | 531 | 58.0 | 299 | 63.9 | 232 | 51.8 |

| Graduate | 329 | 35.9 | 160 | 34.2 | 169 | 37.7 | |

| Postgraduate | 56 | 6.1 | 9 | 1.9 | 47 | 10.5 | |

| Occupation | Student | 401 | 43.8 | 108 | 23.1 | 293 | 65.4 |

| Part-time job | 448 | 48.9 | 360 | 76.9 | 88 | 19.6 | |

| Full-time job | 67 | 7.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 67 | 15.0 | |

| Household | 1 person | 287 | 31.3 | 232 | 49.6 | 55 | 12.3 |

| 2–3 people | 376 | 41.0 | 166 | 35.5 | 210 | 46.9 | |

| 4–5 people | 234 | 25.5 | 61 | 13.0 | 173 | 38.6 | |

| >5 people | 19 | 2.1 | 9 | 1.9 | 10 | 2.2 | |

| Responsible for purchasing groceries for the household | Yes | 506 | 55.2 | 369 | 78.8 | 137 | 30.6 |

| No | 410 | 44.8 | 99 | 21.2 | 311 | 69.4 | |

| Construct | Items | Portugal (N = 448) | Norway (N = 468) | Total Sample (N = 916) | Factor Loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D | Mean | S.D | Mean | S.D | Skewness | Kurtosis | Initial | Revised | ||

| COL | COL1 | 2.94 | 0.94 | 3.05 | 0.96 | 3.00 | 0.95 | −0.11 | −0.26 | 0.586 | 0.579 |

| COL2 | 3.99 | 0.85 | 3.57 | 0.88 | 3.78 | 0.89 | −0.48 | −0.03 | 0.386 | (*) | |

| COL3 | 3.40 | 0.96 | 3.32 | 0.86 | 3.36 | 0.91 | −0.24 | −0.08 | 0.781 | 0.777 | |

| COL4 | 3.23 | 0.98 | 3.21 | 0.94 | 3.22 | 0.96 | −0.21 | −0.22 | 0.762 | 0.791 | |

| COL5 | 3.01 | 0.98 | 2.89 | 0.96 | 2.95 | 0.97 | −0.02 | −0.30 | 0.567 | (*) | |

| COL6 | 3.13 | 0.99 | 2.94 | 0.91 | 3.03 | 0.95 | −0.08 | −0.25 | 0.531 | (*) | |

| HC | HC1 | 3.75 | 0.86 | 3.65 | 0.91 | 3.69 | 0.89 | −0.60 | 0.35 | 0.692 | 0.699 |

| HC2 | 3.86 | 0.83 | 3.50 | 0.97 | 3.68 | 0.92 | −0.55 | 0.10 | 0.834 | 0.847 | |

| HC3 | 3.94 | 0.89 | 3.32 | 1.02 | 3.62 | 1.01 | −0.47 | −0.32 | 0.539 | (*) | |

| EC | EC1 | 4.48 | 0.72 | 3.87 | 0.87 | 4.17 | 0.86 | −0.84 | 0.29 | 0.724 | 0.723 |

| EC2 | 4.51 | 0.71 | 3.97 | 0.80 | 4.23 | 0.80 | −0.85 | 0.42 | 0.601 | 0.602 | |

| EC3 | 4.58 | 0.66 | 3.42 | 0.93 | 3.99 | 1.00 | −0.71 | −0.19 | 0.815 | 0.816 | |

| ATT | ATT1 | 4.08 | 0.78 | 3.66 | 0.89 | 3.86 | 0.86 | −0.62 | 0.51 | 0.796 | 0.82 |

| ATT2 | 3.88 | 0.85 | 3.60 | 0.96 | 3.74 | 0.92 | −0.63 | 0.51 | 0.779 | 0.805 | |

| ATT3 | 3.88 | 0.88 | 3.50 | 0.98 | 3.68 | 0.95 | −0.71 | 0.51 | 0.781 | (*) | |

| ATT4 | 4.01 | 0.81 | 3.70 | 0.87 | 3.85 | 0.86 | −0.63 | 0.55 | 0.741 | 0.738 | |

| SN | SN1 | 2.67 | 1.03 | 1.87 | 0.99 | 2.26 | 1.08 | 0.45 | −0.59 | 0.829 | 0.828 |

| SN2 | 2.54 | 0.99 | 2.11 | 1.06 | 2.32 | 1.05 | 0.30 | −0.65 | 0.871 | 0.872 | |

| SN3 | 2.65 | 0.97 | 2.09 | 1.03 | 2.36 | 1.04 | 0.21 | −0.69 | 0.891 | 0.891 | |

| SN4 | 2.75 | 1.05 | 2.17 | 1.06 | 2.45 | 1.09 | 0.23 | −0.85 | 0.551 | 0.55 | |

| PP | PP1 | 1.83 | 0.72 | 1.91 | 0.80 | 1.87 | 0.76 | 0.56 | −0.13 | 0.365 | (*) |

| PP2 | 2.95 | 0.89 | 2.71 | 0.88 | 2.83 | 0.89 | −0.15 | −0.21 | 0.768 | 0.901 | |

| PP3 | 2.81 | 0.93 | 2.73 | 0.93 | 2.77 | 0.93 | −0.05 | −0.34 | 0.744 | 0.623 | |

| AV | AV1 | 2.71 | 0.82 | 3.01 | 0.89 | 2.86 | 0.87 | 0.05 | −0.22 | 0.582 | 0.581 |

| AV2 | 2.90 | 0.88 | 3.36 | 0.90 | 3.14 | 0.92 | −0.01 | −0.63 | 0.815 | 0.815 | |

| AV3 | 2.79 | 0.88 | 3.43 | 0.84 | 3.12 | 0.92 | −0.15 | −0.42 | 0.852 | 0.852 | |

| INT | INT1 | 3.98 | 0.86 | 3.01 | 1.04 | 3.48 | 1.07 | −0.50 | −0.21 | 0.87 | 0.873 |

| INT2 | 3.76 | 0.92 | 2.96 | 1.09 | 3.35 | 1.09 | −0.38 | −0.32 | 0.891 | 0.894 | |

| INT3 | 3.64 | 0.94 | 3.02 | 0.99 | 3.32 | 1.02 | −0.41 | −0.18 | 0.85 | 0.845 | |

| BEH | BEH1 | 1.16 | 1.09 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.83 | n.a | n.a |

| Construct | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Availability | 0.80 | 0.58 | 0.76 | |||||||

| Collectivism | 0.76 | 0.52 | 0.03 | 0.72 | ||||||

| Health consciousness | 0.75 | 0.61 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.78 | |||||

| Environmental concern | 0.76 | 0.52 | −0.19 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.72 | ||||

| Attitude | 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.79 | |||

| Subjective norms | 0.87 | 0.64 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.80 | ||

| Perceived price | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.77 | |

| Intention | 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 0.41 | 0.87 |

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Intention → Behavior | 0.400 | 0.042 | 11.918 | 0.001 | 0.160 |

| H2: Attitude → Intention | 0.583 | 0.040 | 16.984 | 0.001 | 0.616 |

| H3: Subjective Norms → Intention | 0.305 | 0.026 | 10.574 | 0.001 | |

| H4: Perceived price → Intention | 0.156 | 0.037 | 4.258 | 0.001 | |

| H5: Availability → Intention | −0.007 | 0.045 | −0.240 | 0.810 | |

| H6: Health consciousness → Intention | 0.236 | 0.041 | 7.172 | 0.001 | |

| H7: Environmental concern → Intention | 0.222 | 0.039 | 7.192 | 0.001 | |

| H8: Collectivism → Attitude | 0.169 | 0.053 | 4.093 | 0.001 | - |

| H9: Collectivism → Subjective Norms | 0.258 | 0.067 | 6.289 | 0.001 | - |

| H10: Collectivism → Perceived price | 0.184 | 0.061 | 4.359 | 0.001 | - |

| H11: Collectivism → Availability | 0.035 | 0.038 | 0.851 | 0.395 | - |

| H12: Collectivism → Health consciousness | 0.061 | 0.051 | 1.426 | 0.154 | - |

| H13: Collectivism → Environmental concern | 0.219 | 0.051 | 4.996 | 0.001 | - |

| Comparison | χ2 (df) | Difference (from Base Model) | Standardized Estimate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 (df) | p | Norway | Portugal | |||

| Model | Unconstrained (Base Model) a | 1267.07 (482) | - | - | - | - |

| Constrained (All Variables) b | 1294.722 (495) | 27.653 (13) | 0.010 | - | - | |

| Path Name | Collectivism → Attitude | 1267.213 (483) | 0.144 (1) | 0.705 | 0.125 * | 0.207 ** |

| Collectivism → Subjective Norms | 1267.08 (483) | 0.011 (1) | 0.915 | 0.237 ** | 0.261 ** | |

| Collectivism → Perceived Price | 1267.195 (483) | 0.126 (1) | 0.723 | 0.187 ** | 0.164 ** | |

| Collectivism → Availability | 1269.013 (483) | 1.944 (1) | 0.163 | −0.007 | 0.125 * | |

| Collectivism → Health Consciousness | 1267.099 (483) | 0.03 (1) | 0.863 | 0.039 | 0.063 | |

| Collectivism → Environmental Concern | 1268.946 (483) | 1.877 (1) | 0.171 | 0.263 ** | 0.207 ** | |

| Attitude → Intention | 1267.52 (483) | 0.451 (1) | 0.502 | 0.551 ** | 0.720 ** | |

| Subjective Norms → Intention | 1281.595 (483) | 14.526 (1) | 0.001 | 0.327 ** | 0.181 ** | |

| Perceived Price → Intention | 1270.441 (483) | 3.372 (1) | 0.066 | 0.174 ** | 0.100 * | |

| Availability → Intention | 1267.998 (483) | 0.929 (1) | 0.335 | 0.038 | 0.118 ** | |

| Health Consciousness → Intention | 1267.208 (483) | 0.138 (1) | 0.710 | 0.214 ** | 0.266 ** | |

| Environmental Concern → Intention | 1267.666 (483) | 0.597 (1) | 0.440 | 0.109 * | 0.072 | |

| Intention → Behavior | 1268.055 (483) | 0.986 (1) | 0.321 | 0.502 ** | 0.381 ** | |

| Path | Support to Hypothesis | Multi-Group Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Pt | Interpretation | ||

| Collectivism → Attitude | S | Sig. | Sig. | There is no difference across groups (Δ χ2 (df) = 0.144 (1), p > 0.05). |

| Collectivism → Subjective Norms | S | Sig. | Sig. | There is no difference across groups (Δ χ2 (df) = 0.011 (1), p > 0.05). |

| Collectivism → Perceived Price | S | Sig. | Sig. | There is no difference across groups (Δ χ2 (df) = 0.126 (1), p > 0.05). |

| Collectivism → Availability | R | N. Sig. | Sig. | The positive relationship between Availability and Collectivism is only significant for Portugal. The path does not differ across groups (Δ χ2 (df) = 1.944 (1), p > 0.05). |

| Collectivism → Health Consciousness | R | N. Sig. | N. Sig. | There is no difference across groups (Δ χ2 (df) = 0.03 (1), p > 0.05). |

| Collectivism → Environmental Concern | S | Sig. | Sig. | There is no difference across groups (Δ χ2 (df) = 1.877 (1), p > 0.05). |

| Attitude → Intention | S | Sig. | Sig. | There is no difference across groups (Δ χ2 (df) = 0.451 (1), p > 0.05). |

| Subjective Norms → Intention | S | Sig. | Sig. | The positive relationship between Subjective Norms and Intention is stronger for Norway. The path differs across groups (Δ χ2 (df) = 14.526 (1), p < 0.01). |

| Perceived Price → Intention | S | Sig. | Sig. | The positive relationship between Perceived price and Intention is stronger for Norway. The path does not differ across groups (Δ χ2 (df) = 3.372 (1), p > 0.05). |

| Availability → Intention | R | N. Sig. | Sig. | The positive relationship between Availability and Intention is only significant for Portugal. The path does not differ across groups (Δ χ2 (df) = 0.929 (1), p > 0.05). |

| Health Consciousness → Intention | S | Sig. | Sig. | There is no difference across groups (Δ χ2 (df) = 0.138 (1), p > 0.05). |

| Environmental Concern → Intention | S | Sig. | N. Sig. | The positive relationship between Environmental concern and Intention is not significant for Portugal. The path does not differ across groups (Δ χ2 (df) = 0.597 (1), p > 0.05). |

| Intention → Behavior | S | Sig. | Sig | There is no difference across groups (Δ χ2 (df) = 0.986 (1), p > 0.05). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roseira, C.; Teixeira, S.; Barbosa, B.; Macedo, R. How Collectivism Affects Organic Food Purchase Intention and Behavior: A Study with Norwegian and Portuguese Young Consumers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127361

Roseira C, Teixeira S, Barbosa B, Macedo R. How Collectivism Affects Organic Food Purchase Intention and Behavior: A Study with Norwegian and Portuguese Young Consumers. Sustainability. 2022; 14(12):7361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127361

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoseira, Catarina, Sandrina Teixeira, Belem Barbosa, and Rita Macedo. 2022. "How Collectivism Affects Organic Food Purchase Intention and Behavior: A Study with Norwegian and Portuguese Young Consumers" Sustainability 14, no. 12: 7361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127361

APA StyleRoseira, C., Teixeira, S., Barbosa, B., & Macedo, R. (2022). How Collectivism Affects Organic Food Purchase Intention and Behavior: A Study with Norwegian and Portuguese Young Consumers. Sustainability, 14(12), 7361. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127361