Abstract

This article covers the current research vacuum on how Guatemala partially conducts forest preservation through community concessions. Our paper starts its analysis by synthesizing the private property-rights approach environmentalist theory and the community concession theory. It is argued that the shared common private property as a community arrangement can turn conflicts into potential opportunities for the involved parties to solve the existing environmental problems by win-win games. Based on the above theoretical views, our study extends the scope to the modern and democratic municipals’ forest preservation in Guatemala, as previous research mainly focused on how the Guatemalan traditional indigenous communities have conducted forest preservation. Our empirical results show that the in-force forest concessions in the Maya Biosphere Reserve have achieved the Guatemalan government’s forest conservation target in recent years. However, as the Guatemalan forest concession arrangements are just usufructs and the state still owns forest titles, the current Guatemalan forest concession could reverse the result of the limited, decentralized forest reform. In this regard, we suggest that Guatemala state should privatize all these forests to the concessions’ communities and firms. If the results are positive, we propose the Guatemalan government further apply the decentralization forest policy to the whole country.

1. Introduction

As a third-wave democracy, Guatemala has suffered an internal armed conflict of considerable magnitude like other republics in Latin America [1]. Since its democratization, the country has been unable to find a clear direction toward the long-awaited economic development [2,3]. Despite the above problems, Guatemala still has highlights in environmental protection affairs. Although it lacks economic growth [4], the community-based rural, peripheral, and indigenous world conducts successful forest conservation and provides highly qualified agricultural and forest exportations [5]. The community identity plays a vital role in Guatemala’s environmental protection issues [6,7].

This article aims to cover the current research vacuum on how Guatemala partially conducts forest preservation through community concessions, as previous empirical research mainly focused on how the Guatemalan traditional indigenous communities have conducted forest preservation. We consider that the in-force forest concessions in the Maya Biosphere Reserve (RBM, for its acronym “Reserva de la Biósfera Maya” in Spanish) have achieved the Guatemalan government’s forest conservation target. It shows how forest concessions as community arrangements help local communities and local firms not only protect the forests, but also make their economy competitive.

Our paper starts its analysis by combining the private property-rights approach environmentalist (PAE) theory and the community concession (CC) theory. Wang et al. argued that the traditional top-down environmental policy assumes that central planning possesses or can acquire the relevant knowledge and prices to design a prosperous economy [8]. They considered that this assumption was initially challenged one hundred years ago by Ludwig von Mises [9] and later by the 1974 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences winner Fredrich A. Hayek [10]. He contended that a central body such as the government could not concentrate the relevant knowledge for economic success and the use of resources. In fact, knowledge is scattered among agents in society due to its very local, tacit, subjective, exclusive, and personal nature [11]. Additionally, prices and production are coordinated in the decentralized market economy [9]. This reasoning breaks with any top-down and centralized policy program, advocating a bottom-up and decentralized view of policymaking, respecting the latter initiative’s role in providing environmental protection and sustainability. Moreover, Wang et al. argued that many authors had approached the study of environmental issues based on this Hayekian approach [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Both theory and empirical evidence have shown how decentralized alternatives achieve environmental transformations and, conversely, how centralized policies fail to attain the expected and planned policy objectives.

The PAE theory defines environmentalism as the science that studies human beings’ relations with each other and their environment [15]. The PAE theory considers that the existing decentralized and spontaneous market process propelled by the creative entrepreneurship coordinates better with and adjusts better for the rest of the species and elements of the natural environment than the centralized planned economy [15].

The CC theory was developed during the second half of the 20th century by Vincent Ostrom [18] and the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences winner Elinor Ostrom [19]. The CC theory sees community concession as a polycentric reality and the third way between nationalization and privatization [18]. Elinor Ostrom’s work has been interpreted as a reaction to Garret Hardin’s The Tragedy of the Commons [20]. The latter’s work recommended privatization as an easy, viable, and quick solution to the famous tragedy of the commons. Vincent and Elinor Ostrom react against this claim, arguing that, in some situations, community property management may be more effective—and more beneficial and legitimate—than simply privatization itself. Based on the contribution of the community concession approach, this paper discusses concessions as usufructs for community use. Although the Ostroms did not consent that the community arrangement could be a potential private property, we consider that the CC theory can cooperate with the PAE criteria if the concession is treated as a transition towards a shared private property. Moreover, we reckon that as the state still owns forest titles, the current Guatemalan forest concession could reverse the result of the limited, decentralized forest reform.

The article is organized in the following structure. Section 2 provides our research methodology and background. Section 3 studies the modern forest concession institutions in the Maya Biosphere Reserve (RBM). Section 4 shows our research results. Section 5 is our discussion of future research proposals. Section 6 is the conclusion.

2. Research Methodology and Background

This section introduces our research methodology and background. Section 2.1 provides the fundamental theoretical tools we use in this research: the private property-rights approach environmentalist theory and the community concession theory. Section 2.2 provides the fundamental concepts involving forest conservation. Section 2.3 reviews previous research on the Guatemalan communities’ forest management. Section 2.4 illustrates Guatemala’s centralized political institution and its failed rationalization of land policy. Section 2.5 reviews Guatemala’s traditional indigenous communities’ forest arrangements.

2.1. Property-Rights Approach Environmentalist Theory and the Community Concession Theory

2.1.1. Private Property-Rights Approach Environmentalist Theory

The PAE theory, also named free-market environmentalism, has been continuously developed by the Austrian school economists represented by Ludwig von Mises, Fredrich von Hayek, and Jesús Huerta de Soto since the early 20th century. It defines environmentalism as the science that studies human beings’ relations with each other and their environment [15]. The PAE theory considers that the entrepreneurship-based market process coordinates better with and adjusts better for the rest of the species and elements of the natural environment than the centralized planned economy [15].

The PAE theory considers three fundamental problems with any centrally planned environmental policy. The first is the impossibility of economic calculation through central planning. The exact identification of private property rights gives the property owner the incentive to protect the environment in which he lives and sue anyone who violates his property’s environment. In contrast, the lack of private property generates the tragedy of the commons, and the environment is polluted without the incentive to protect it [13,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. When property rights are violated, human beings cannot act as they want because the necessary information and price signals are disturbed. Therefore, even the most radical environmentalists cannot ensure that their centrally planned proposals would not cause even more environmental damage [15].

Secondly, nationalizing natural resources as public property prevents economic calculation and undermines entrepreneurship [15]. As the market economy’s driving force [28,29], based on price signals, the entrepreneurs make better decisions and allocate resources more efficiently to protect the environment than the central planning of governments. However, when natural resources are nationalized, it becomes impossible for entrepreneurs to make economic calculations. Therefore, the related environmental-friendly products might not be produced due to the missing role of entrepreneurship.

Thirdly, zero-sum games are created through public policies and legislative decisions, while the market might solve these problems. Governmental orders substitute voluntary contracts and actions [15,30,31,32]. Conflicts might be solved by voluntary negotiations. However, state legislation might cause the unexpected “one party wins, and the other loses” consequence. Furthermore, incomprehensible legislation could cause the inefficiency of resource allocation through interventionism and regulation. Then, there is no way for the consumers and producers to internalize the costs and benefits of environmental protection-related production, and a zero-sum game is created by state legislation.

2.1.2. The Community Concession Theory

The CC theory sees community concession as a polycentric reality and a third way between complete nationalization of the resource and privatization [18]. It was developed during the second half of the 20th century by the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics winner Elinor Ostrom [19] and her husband Vincent Ostrom [18]. Their works have been interpreted as a reaction to Garret Hardin’s The Tragedy of the Commons [20]. The latter’s work recommended privatization as an easy, viable, and quick solution to the famous tragedy of the commons. Vincent and Elinor Ostrom challenged this claim by pointing out that, in some situations, common-pool resources (CPR) management may be more effective, beneficial, and legitimate than privatization itself.

The CC theory considers that the rules of local governance and institutions could turn potential conflicts into opportunities by applying the 1974 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences winner Fredrich A. Hayek’s insight on the function of local knowledge [33,34]. E. Ostrom argued that any scientific knowledge has its limitation as any constricted model cannot fully explain the diversity of CPR problems [19] (p. 24). Therefore, it is essential to study how different local and self-organizations solve conflicts without top-down planning [19] (pp. 24–25).

Furthermore, the CC theory emphasizes the importance of empirical studies on how the community arrangements solve environmental-related problems [19,34]. E. Ostrom herself stressed the importance of community arrangements in developing countries [35,36]. Peter Boettke contended that E. Ostrom “has demonstrated in a variety of historical circumstances and within a diversity of institutional environments how individuals can craft rules so that they can live better together in their communities and realize the gains from social cooperation under the division of labor” [33]. Some excellent and widely cited cases of E. Ostrom’s studies include the mountain grazing in Switzerland and irrigation systems in Spain. She argued that it was local internal rules and monitoring arrangements that disciplined temptations to violate community rules, ensuring robust conformity to those rules of governing the CPR [19] (pp. 58–102, cited by Boettke [33]).

Therefore, it is the community arrangements that turn conflicts into potential opportunities for both parties to solve the existing environmental problems by win-win games. The Hardinian “tragedy of the commons” then could be solved. Interestingly, in his later work, Hardin changed his mind, recognizing that the tragedy of the commons could be managed and avoided [37]. Although he did not mention the role of private property or the concept of local knowledge directly, he recognized that the common pool could be managed well by its group owners if there is an advance in the scientific capacity of common good management.

2.1.3. The Common Grounds of the Two Norms

Although the CC theory treats the common good criteria as a third way to solve the dilemma between the government solution and the pure private-property approach, it is still considered that the CC theory cooperates with the PAE criteria. In the first place, private ownership is the first common ground between the above two norms. The private-property approach economist Ludwig von Mises defined private ownership as “full control of the services that can be derived from a good” [28] (p. 678). Hence, once a person can fully restrain on a particular property, he is the de facto owner of this property. Walter Block reckoned that private property right does not mean that only a single individual has control over a definite resource [38]. He argued that if a common good is fully controlled by a group of the pool users, it is considered a jointly owned private property by these users. Boettke further emphasized that E. Ostrom’s common-pool resources theory cooperates with the private property approach [33]. He argued that what Ostrom has demonstrated [39] is: the rules in use determine practice rather than the rules in form. Therefore, the function of private property could be served by different forms of rules. Furthermore, although some types of common-pool resources are owned by the state as the so-called “public goods,” if in practice, the group of users of this property has full control of the services derived from it, this common-pool good is the de facto private property. In this regard, we consider that both the PAE criteria and the CC theory cooperate with each once the common-pool joint users have full control of this common property.

Secondly, in environmental protection teams, both the PAE and CC recognize the role of decentralized political institutions and oppose the nationalization of natural resources and the conflicts caused by legislative decision-making. The PAE criteria shown in Section 2.1.1 above implies that central planning institutions cannot acquire the relevant knowledge and prices to design a prosperous economy. If the central planning bodies cannot coordinate knowledge and prices, it might create discoordination or even zero-sum games among the involved parties as the conflicts could have been solved by them without the central government’s intervention. The above argumentation discontents with any top-down and centralized policy program, advocating a bottom-up and decentralized view of policymaking. Therefore, both theories opposed the economic inefficiency caused by nationalizing natural resources and precluding the zero-sum games created by legislative bodies. Hence, the above insights cooperate with the CC’s proposal on decentralization and community arrangements.

2.1.4. The Guatemalan Community Concession: A Step towards a Jointly Owned Private Property

Our above analysis has shown that the CC theory and the PAE criteria can cooperate with each other if the community has full control of this jointly owned property. However, as we have illustrated above, E. Ostrom’s proposal does not exclude another scenario of CC: the community can only make some limited decisions for the common good, if the state still regards the common property as its “public good”. The Guatemalan CC case that we analyze in this paper matches the traditional public-good scenario CC. Due to the Guatemalan Forest Law [40], the forest concession is defined as a usufruct through which the state authorizes the use of its partial territories to an individual, a company, or a community. This usufruct arrangement does not refer to the privatization of property to an individual or an enterprise, but a kind of rent for the local community to manage the natural resource in a sustainable way. In this regard, we consider that the current Guatemalan forest concession is a transitional step towards a jointly owned private property.

2.2. Key Concepts Involving Forest Conservation

This section provides some key concepts related to forest conservation. Forest conservation (forest preservation) is defined as “the practice of planting and maintaining forested areas for the benefit and sustainability of future generations” [41]. The concept also aims at a quick shift in the composition of tree species and age distribution. In forestry, forest protection is defined as a concept “concerned with the prevention and control of damage to forests arising from the action of people or livestock, of pests and abiotic agents” [42]. Therefore, forests can be preserved sustainably for future generations by preventing and controlling forest damage. In our case, although the Guatemalan state’s National Council of Protected Areas (CONAP) did not provide a clear definition of what is reforestation or the improvement of forest condition, it can be assumed from the same document that the concept refers to the natural regeneration of forests to the places that did not have it before the regrowth process [43]. Forest degradation (forest loss or deforestation) is defined as a condition “when forest ecosystems lose their capacity to provide important goods and services to people and nature” [44].

2.3. Previous Research on the Guatemalan Communities Forest Management

Previous research has studied Guatemala’s communities’ forest management, providing a substantial base for further analysis. Pacheco et al. pointed out that spontaneous indigenous societies had started to protect forests in the later 19th century in Latin American countries [45]. Veblen argued that Guatemala’s forest degradation accelerated in the 1930s and the 1940s due to planned development projects and colonization [46]. On the other hand, he argued that the indigenous communities conducted forest preservation better as they were far from cities, and the forest was in inaccessible areas. Hess studied Guatemala’s traditional indigenous forest conservation, arguing the venerability and forest degradation of these institutional arrangements [47]. He discussed that the overuse of carpentry livelihoods, the state regulations, and the lack of management capacity prevent the aboriginal communities from efficiently managing their forest conservation. He proposed the necessity of educating the indigenous communities on how to allocate natural resources in an eco-friendly way. Although the author cited two of E. Ostrom’s works on ecological protection [35,36], he did not apply Ostrom’s CC theory to the case of Guatemalan forest preservation.

By applying Ostrom’s CC theory [19], Elias and Wittman argued that local institutions (including NGOs) played an important role in the management and administration of communal forest resources inside the indigenous communities [48]. However, they discovered that the lack of funding and the unclearness of property titles had impeded forest conservation. On the other hand, they criticized Guatemala’s centralized political institutions, since the 1996 Forest Laws [40] provide very limited space for decentralization. They reckoned that the Law only assigns responsibilities to municipalities, but is not linked to other decentralization initiatives, such as the more general decentralization laws (The Decentralization Law [49] and The Municipal Code [50]) passed in 2002. These laws require the implementation of urban and rural development councils. In another paper, Elias reckoned that the indigenous peoples have the right to control the collective natural resource management, proposing to create new governance policies to respect the collective groups [51]. Wittman and Geisler further warned that the current Guatemalan political decentralization actually centralized political power at the local level, generating corruption and weakening successful village-level forest governance structures and local livelihoods [52]. By using the quantitative method, Priebe et al. discovered [53] that in some higher population and road densities areas, deforestation and reforestation rates increased with a net forest cover growth after the forest management decentralization since 1996. They also argued that the number of employees dedicated to forestry activities is the most significant social variable in reforestation efforts during the post-decentralization era. Reddy claimed that the local indigenous forest management is the de facto common private property [54]. While the above literature provides us with many insightful observations on the local indigenous arrangements of forest and natural resource protection in Guatemala, there is still a lack of relevant research on modern communities’ arrangements for forest preservation. This affair then becomes the focus of our paper.

2.4. Guatemala’s Centralized Political Institution with a Failed Forest Nationalization

Guatemala is considered a highly centralized presidential republic. Its constitution has defined its centralist and unitary political features since its democratization in 1985 [55]. For fiscal policy, the Guatemalan central government has an important decision-making role. Article 257 of the Constitution requests its central government’s executive branch to distribute only 10% of its annual general budget to its 340 municipalities [55]. In other words, 90% of the state income is consumed by the central government [56].

Guatemala’s forest policy also reflects the country’s centralist political institutions. It has a high degree of forest nationalization and concentration [56]. Its 2002-03 National Forest Inventory estimated that the possession of Guatemala’s forests was: 34% of national property, 8% of municipal property, 38% of private property, 15% of communal property, and 5% not determined [57]. Furthermore, 77% of smallholders (with less than 7 hectares per person) work on only 15% of productive land [57]. Therefore, the smallholders only own around 30% of the country’s whole land.

The above forest policy features are deeply embedded in its long-standing history of the interventionist natural-resource policy. The model can even be traced back to the 19th century after its independence in 1821. The Guatemalan ecologist Prado-Córdova considered that the country’s land policy was being shaped by the decision-making of the country’s ruling vested interest groups at the beginning of the Guatemalan independence [56]. In the name of privatization during the last quarter of the 19th century, these groups acquired the aboriginals’ lands by forces and political mandate, confiscating them as their private properties [41]. The Catholic Church accumulated and expropriated lands through legislative justification, utilizing the lands by forced peasant labors. Among them, most laborers were the indigenous people [56]. Therefore, Guatemala’s land policy results from state-interventionist policy and power games, not the normative privatization. The latter standard should be executed based on voluntary actions instead of state coercion [11].

However, Guatemala continued its state-interventionist land reform, no matter whether in the name of privatization or nationalization. In 1952, President Jacobo Árbenz and his government carried out the famous Guatemalan Agrarian Reform (Decree 900). The reform planned to favor a more equitable land distribution to local farmers (mostly the indigenous people) through a state coercive land redistribution policy. Due to Decree 900, any uncultivated land larger than 673 acres (2.72 km2) was taken by the government. If the estate was between 672 acres (2.72 km2) and 224 acres (0.91 km2) in size, only those with less than two-thirds of the cultivated area would be confiscated [58] (pp. 149–164). Landlords would receive government bonds (equal to the values of the confiscated land calculated through the landowner’s tax return in 1952) as compensation (pp. 149–164). The local governments would set up a government committee to decide the redistribution to laborers (pp. 149–164). Of the nearly 350,000 pieces of private land, only 1,710 were confiscated (pp. 149–164). However, not only did Decree 900 spark domestic discontent in Guatemala, but it also eventually led to the CIA’s involvement as the U.S. government worried about the consequence of the communism-based land reform (pp. 222–225). The Árbenz government was overthrown in 1954 by a U.S.-led coup, while Decree 900 and the land reform were canceled.

It is argued that the 1952 Agrarian Reform caused conflicts between Guatemalan social classes and has caused long-run consequences for the country till today, influencing its environmental policies. Guatemalan sociologist Torres-Rivas argued that land reform was one of the triggers for the 30-year Civil War (1960–1996) [59]. The World Bank considered that the 19th land reform, Decree 900, and the upcoming Civil War created barriers for a large party of the Guatemalan citizens to receive the benefits of globalization: they could not use natural capital and resources that existed in their communities as both the state and a small group of elites have controlled the majority of land resources [60]. Therefore, most Guatemalans did not participate in the decision-making regarding the use of natural capital and did not receive the benefits of the ecological protection goal proposed by the Guatemalan government [60]. To get more opinions, we interviewed two Guatemalan specialists who thoroughly studied the country’s land policy. Historian Rodrigo Fernández reckoned that the above policies have led to unclear land ownership, increasing social conflict, and political instability. As property titles are not settled, different individuals and interest groups have been contesting to obtain the titles, causing a zero-sum game due to public legislative decision-making. Ecologist Óscar Rojas believed the conflicting land policies have ecological consequences. Deforestation in Guatemala has been ramped up because of the tragedy of the commons or the transformation of the rural sector (from agriculture to extensive livestock farming), resulting in uncontrolled resource use.

2.5. The Traditional Indigenous Communities’ Forest Arrangements

Apart from the above unsuccessful land nationalization, as we have mentioned in Section 2.3, several traditional indigenous communities conduced forest conservation even before the independence of Guatemala. To better compare the conventional indigenous forest preservation model and the modern communities’ arrangements, this section introduces the well-studied case of Totonicapán shortly, an executive department in the west of the country [46,47,48,51,52,53,54]. Totonicapán is one of the Guatemalan departments with the lowest territorial extension in the country (1061 km2), the highest population density (256 inhabitants/km2), and the highest rate of smallholding [61]. Furthermore, it is a department with the highest percentage of forest cover (60%), respecting its territorial extension [61].

Totonicapán had become a bottom-up forest preservation case even when it was still a part of the Spanish Crown. In the era of the Spanish Conquest, it was one of the most densely settled areas in Middle America [46] The local cantons bought the exploitation and conservation rights from the Spanish Kingdom in 1811, ten years before the Guatemalan independence. Since that time, instead of the central authority, it is the cantons (through a Board of Directors) that control sustainability and regulate the exploitation of the resource [62]. The whole forest consisted of more than 220 km2 [63], being considered a well-protected forest area compared with many regions in Middle America [46]. Since 1985, Guatemala’s democratic constitution (see its Articles 66, 67, 68, and 69 [55]) also recognizes the indigenous people’s autonomy inside their settled executive departments. This recognition protects the indigenous heritage from a legal perspective.

Four factors are considered the most important reasons why Totonicapán has been conducting forest conservation more efficiently [46]. First, interpersonal relationships are face-to-face there. As the indigenous people generally recognize one another or each family, the absence of anonymity has incentivized the locals’ respect for the established communal forest boundaries. Second, as a powerful special interest group, the carpenters acknowledged that if all of the forests in Totonicapán were transformed into pasture or agricultural land, there would be no other local natural resource as an alternative. Therefore, they encourage the indigenous communities to maintain vigilance over the communal forest use and punish those who cut wood illegally. Third, in general, the Totonicapán indigenous population is willing to retain its independent identity and control the local affairs as much as possible. The motivation for self-sufficiency encourages the maintenance of traditional forest resource exploitation. Fourth, the decision-making in the Totonicapán department is decentralized. This structure helps the local indigenous communities negotiate their common interest more efficiently.

The forest management structure of the Baquiax faction of Totonicapán is an excellent example. The Guatemalan State has recognized the Baquiax faction as a form of autonomous community organization since 1953. Unlike other democratic administrative divisions in Guatemala, family lineages (with paternal kinship ties) make the decision-making of forest conservation in Baquiax. Their governing roles include: (1) the use and defense of forests; (2) strengthening forestry administration; and (3) monitoring forestry activities [61]. Furthermore, the Baquiax faction has only a few members who make executive decisions on the Board of Natural Resources Directors (Junta de Condueños in Spanish). The Board aims to protect forest resources and construct sustainable forest exploitation that benefits the 48 cantons in Totonicapán. As of 2007, there were 44 members of the Board, including 14 women and 30 men [61]. The limited members in the Board have shortened the policymaking process with fewer arguments and more efficiency [61].

Women play important roles in the community decision-making process. In the case above, the proportion of female Board members was almost half of the male ones. Moreover, in the Baquiax faction, 14 of the 44 community owners of the forest are women [61]. Some of them have become the top leaders of the indigenous environmental protection organizations in the last 20 years. In 2012, Andrea Ixíu, an indigenous activist and communicator, was elected as the Board’s first female president. The above facts have shown clearly that the Baquiax faction, as a traditional indigenous institution, respects the female leadership even though it does not implement the modern concept of gender equality.

As we have discussed above, the social-political organizations of Totonicapán are the result of an indigenous institutional evolution through three centuries [48,64]. They have conducted forest preservation in an efficient way inside the indigenous communities. However, their success is not reproducible for the rest of Guatemala’s Hispanic population who live in the modern democratic institutions. These institutions are hardly exportable as the indigenous world enjoys a particular evolution and institutions that have favored their community’s natural resources management. More applicable institutional arrangements should be discussed to solve the forest conservation matter in Guatemala’s modern democratic institutions.

3. The Modern Forest Concession Institutions: The Case of Maya Biosphere Reserve

Compared with the traditional indigenous forest preservation arrangements discussed above, it is necessary to pay attention to the modern forest concession institutions in Guatemala. As they are based on constitutional and democratic mechanisms, their model could be applied to other Guatemalan executive departments and even other Latin American countries who are facing similar forest conservation challenges. This section discusses RBM as Guatemala’s modern forest concession institution. Section 3.1 introduces Guatemala’s state regulations on forest concessions. Section 3.2 shows the active and inactive concessions within the RBM. Section 3.3 and Section 3.4 separately deal with RBM’s forest degradation and conservation. This section provides some essential and previously undisclosed official data related to the RBM forest that the official CONAP provided to us in October 2019.

3.1. Guatemala’s State Regulations on Forest Concessions

This subsection introduces Guatemala’s state regulations on its forest preservation purposes, its regulated forest types, and its state regulatory body. As we have discussed in Section 2.3, as a result of a decentralization movement, two laws were passed in 2002 to authorize the decentralized use of land: (1) The Decentralization Law [49] and (2) The Municipal Code [50]. Even though the decentration of power is limited, as we have shown above, these regulations still allow Guatemala’s local communities to conduct forest preservation with their autonomy.

Our research also considers that Forest Law (1996) [40] addresses more legal clauses related to forest concessions. As the Law is strongly connected with the current communities’ roles in forest preservation, it is crucial to provide a detailed introduction. Article 3 of the Law defines forest concession as “a political power that the State grants to the Guatemalans, individual or juridical, so that—at their own risk—they carry out forest exploitation in state-owned forests, with the rights and obligations agreed upon in their granting” [40]. Therefore, this concession arrangement is a usufruct that the Guatemalan state authorizes the use of state lands to a specific individual, company, or community.

The Forest Law also defines the purpose of forest concession as the following [40]:

- Reduce forest degradation and advance the agricultural frontier by increasing land use due to its vocation without omitting the characteristics of soil, topography, and climate.

- Promote reforestation and provide the forest products that the Guatemalan state requires.

- Increase the productivity of existing forests, subject them to rational and sustained management according to their biological and economic potential; promote the use of industrial systems and equipment that help reach the most significant added value to forest products.

- Support, promote, and encourage public and private investment in forestry activities to increase forest resources’ production, marketing, diversification, industrialization, and conservation.

- Conserve the country’s forest ecosystems by developing programs and strategies that promote compliance with the respective legislation.

- Improve the communities’ living standards by increasing the provision of goods and services from the forest to meet the needs of firewood, housing, rural infrastructure, and food.

Moreover, the Forest Law regulates two types of communities’ forest exploitation in Article 1 [40]. The first type is the commercial use of the forest. The Law allows this wood category to obtain monetary benefits by selling the communities’ forest products. The second type is non-commercial use. The Law classifies the non-commercial use of the forest as (a) for scientific research and technological development purposes and (b) for families’ energy consumption (i.e., fuel, fence posts, and constructions). The regulation will determine the maximum permissible volumes. The maximum volumes are five cubic meters of standing wood, while the volumes can be increased if the regulations are modified.

Article 5 and Article 30 of the Law indicate that the National Forest Institute (INAB) is a governmental regulatory body that grants concessions, monitors their operation, and suppresses the forest concessions if the communities’ contracts are not fulfilled. Due to the Articles, the Guatemalans can get the concessions through the following three ways: (1) the community that they live in, (2) their enterprises, and (3) as an individual who wishes to obtain it [40]. The above institutions must request concessions from the National Forest Institute (INAB). Once the INAB approves the concession request, the above identities can obtain the usufruct of the forest.

The concession monitoring period carried out by INAB will take place at least once a year. Furthermore, due to Article 30, the concessions will last between 25 and 50 years [40]. The same article also indicates that the Guatemalan state should send inspectors to the communities to review whether the concessions’ forests are well protected each year. If the communities do not match the state regulations, their usufruct will be canceled.

As can be seen, due to the bottom-up and decentralized nature of the legal architecture in force, the concessions provide the local communities initiatives to manage their forest as the communities’ members could receive the economic and non-economic benefits from their own working from the woods. However, it should be noticed that, as the communities’ members do not have full control of forests due to the usufruct nature of the concessions, we consider that the current Guatemalan forest concessions are a transitional step towards a pure common private property approach for forest preservation. This affair will be discussed more in Section 4.

3.2. The Active and Inactive Concessions within RBM

Table 1 shows the active and inactive concessions within the RBM. As of 2022, there have been 14 concessions in Guatemala. Each management unit (MU) belongs to its specific and unique concessionary organization. According to the Forest Law (see Section 3.2) and our field interview in the RBM, two groups of actors play essential roles in forest conservation, management, and timber harvest. The first group is the communities committed to the concessions. They are responsible for exploiting the forest and, at the same time, ensuring its sustainability. Among them, both local autonomous communities and private firms have the right to use the forest concessions. The second group is the Guatemalan government. It monitors the above communities every two years due to the concession regulations that we mentioned above.

Table 1.

Active and inactive concessions within the Mayan Biosphere Reserve.

The current general condition of each MU diversifies. Uaxactún has the largest total area of 83,558 hectares, while the MU San Miguel has the lowest total area of 7.039 hectares. La Ventanas has the biggest number of partners (the number of individuals who have participated in the concession unit), 340, and the management unit Río Chanchich has the least partners, which has a total of 21. The partner numbers of the MUs San Miguel, La Colorada, La Gloria, and Paxbán are not available.

Due to various reasons, such as the willingness to cooperate and economic factors, three MUs are not running currently. The management plan of La Pasadita was suspended, and the projects of San Miguel and La Colorada were canceled due to a breach of contract. The remaining 11 MUs are still running as of 2022. This result shows the success and effectiveness of the concession policy in general.

Among all of the MUs, the first contract started in 1997, and the last was initiated in 2002. As of 2022, all of the 14 MUs have been under the concession for at least 20 years. There are, in total, two types of concessions. In total, 12 of the 14 MUs belong to the community type, while only two belong to the industrial type. They are La Gloria of the BAREN Comercialand Paxbán of GIBOR. It is worth mentioning that both BAREN Comercial and Paxbán are private enterprises. In other words, both local communities, and private firms have the right to use forest lands. This dynamic shows the diversity of Guatemalan concessionary organizations. We argue that this is positive for the further development of the concessionary organizations.

3.3. The Control of Deforestation in the RBM

Table 2 shows the control of deforestation in the RBM from 1989 to 2017. The data show that the concessions granted have served to control deforestation in the RMB. It is calculated that during the period 2000–2010, deforestation in Guatemala took place at a rate of 1.2% of the forest mass, while in the RBM, it was 1.4% [65]. The deforestation rate in the RBM concession areas is less than the rest of the country. The average deforestation rate in the concession area forests has been only 0.024% [65]. Due to the Forest Law [40] and the CONAP report [66], this deforestation rate shows that these concessions, compared with the general forest condition in Guatemala and other areas of the RBM, have reached the Guatemalan state’s requirements of reducing forest degradation and conserving the country’s forest ecosystems. However, due to the lack of data, there have been no other quantitative method to show the specific economic benefits that the Forest Law requires. We consider this vacancy should be the scope analysis of further research.

Table 2.

Deforestation suffered in the RBM, 1989–2017.

As we have argued above, although the Guatemalan state monitors the forest concessions, the local communities play an essential role in forest conservation, management, and timber harvest. They are responsible for exploiting the forest and, at the same time, ensuring its sustainability. Among them, both local autonomous communities and private firms have the right to use the forest concessions. As Section 3.1 has shown, due to the Forest Law [40], the communities can use the wood to obtain monetary benefits by selling the communities’ forest products. Furthermore, they are also allowed to use the forest for scientific research, technological development, and families’ energy consumption (i.e., fuel, fence posts, and constructions). As autonomous communities and private enterprises have the above economic and non-economic incentives, they pay special attention to forest preservation.

3.4. Forest Conservation and its Economic Impacts in the RBM

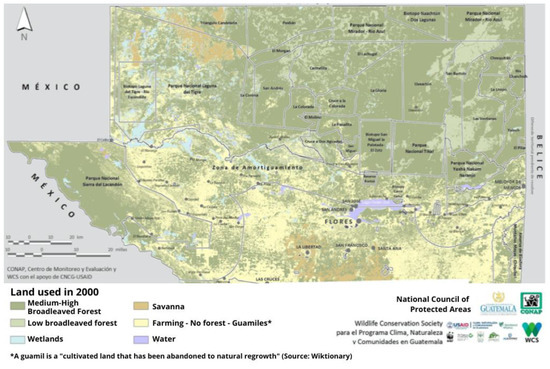

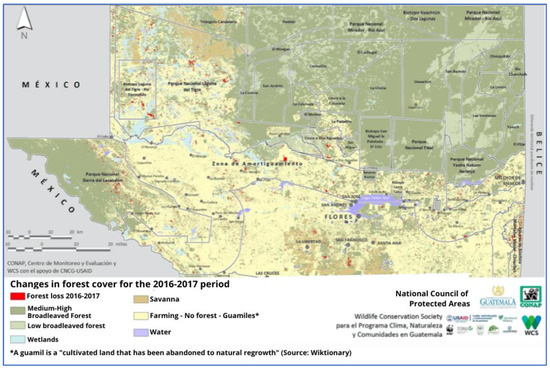

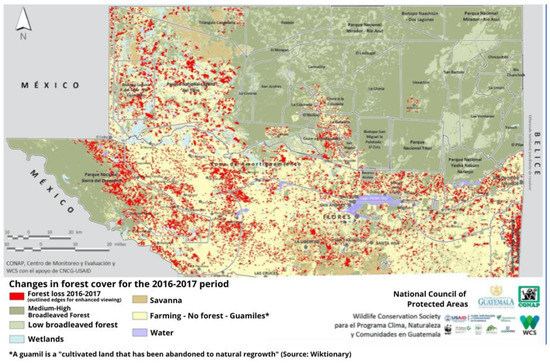

Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the forest conservation flux in the RBM from 2000 to 2017. The three maps include both the areas controlled by the concession units and the destruction of the other regions where concession policy is not applied. The concessions include the abovementioned MUs: Carmelita, Choquistán, La Unión, Las Ventanas, Chanchich River, San Andrés, Uaxactún, Yaloch, and Cruce de la Colorada. As the three maps in the three Figures show together, the official CONAP marked the above concessions as medium-high broadleaved forest (in green color). Due to the Forest Law [40] and the CONAP report [66], these concessions have reached the forest conservation target by the CONAP. These result show that these concessions have effectively conserved the existing forest mass in the area; therefore generalizing the future increasing economic opportunities for the citizens that inhabit there.

Figure 1.

Map 1: Forest cover in the Maya Biosphere Reserve in 2000. Source: Forest cover in the Maya Biosphere Reserve in 2016–2017. Source: Own translation from CONAP [43] (p. 44).

Figure 2.

Map 2: Forest cover in the Maya Biosphere Reserve in 2016–2017. Source: Own translation from CONAP [43] (p. 46).

Figure 3.

Map 3: Forest cover in the period 2016–2017. Source: Forest cover in the Maya Biosphere Reserve in 2016–2017. Source: Own translation from CONAP [43] (p. 46).

As indicated, due to the Forest Law [40] and the CONAP report [66], these concessions have reached the Guatemalan state’s requirements of reducing forest degradation and conserving the country’s forest ecosystems, compared to the deforestation rate in other areas of the country. Table 1 and Figure 1 and Figure 2, when considered together, show that deforestation in the concession areas is almost invisible. The image shows a very different reality in the adjacent regions, which suffer the problems related to the land use, being victims, in some cases, of the tragedy of the commons. Together, the three maps show that other areas where concession policy is not applied have a growing tendency of forest destruction. In Figure 2 and Figure 3, the CONAP marked them as forest degradation areas (red color). The forest degradation areas also include the abovementioned two concessions, San Miguel and La Colorada, as concession policy has been canceled for breaching the usufruct contract.

Apart from the two canceled concessions that did not fulfill forest conservation targets, the rest have been conducting forest conservation efficiently and effectively. As the above data shows, community co-responsibility in resource management and the bottom-up dynamics promoted by the Guatemalan government have worked to fulfill its forest environmental protection objectives.

Furthermore, as we have indicated, the success of the concessions is not limited to forest preservation itself, but benefits the inhabitants there in general. As a result of the concession arrangements, inhabitants have created community forestry companies (EFC). These EFCs have gained importance by exploiting the forests responsibly. In addition to the wood exploitation to produce goods of high added value (for the manufacture of soils, etc.), the EFCs have diversified their activities by participating in active tourism and adventure.

Furthermore, the concessions also bring about incomes for the inhabitants living there. As of 2010, the income resulting from the forest community management represented between 11 and 63% of the revenue generated by the families living in the concessions. The average earnings that came directly from the forest represent 38% of the family income in the 292 owners in the area [65]. In this regard, the concession arrangements have positively helped the local inhabitants take their own initiative and responsibility to protect the forest area and make their own resource allocation.

As a result of the concession policy, the business and sustainable use of the forest—has also increased. It has generated some 58 million USD through 111 small and medium companies employing 8800 individuals [65]. This result shows that the concession policy not only helps to conserve forests but also is profitable. We consider that this outcome indicates that a more market-based institutional arrangement brings a better result than the traditional state planning that Guatemala has adopted since the 19th century. In this regard, we encourage the Guatemalan state to take action to expand the concession policy to the rest of the territories of the country.

In short, compared to other realities in Guatemalan territory, the current concession model in RBM has been conducted effectively. In addition, unlike the traditional, consuetudinary, and ancestral system that Totonicapán adopts (see Section 2.5), the RBM model allows both community and private firms to rule the forests. As mentioned in Section 2.4, the RBM is a system resulting from the Forest Law and the other relevant state regulations. As the institutional concession arrangements have been written as state statutes, they can be easier implemented throughout the country than any system that lacks the rule of law. The above institutional arrangements aim to promote community participation in public policy, enhance economic activities, and protect and even generate an asset in the rich natural territory in Guatemala.

4. Results

This article aims to cover the current research vacuum on how Guatemala partially conducts forest preservation through community concessions. Our paper starts its analysis with the synthesis of the private property-rights approach environmentalist (PAE) theory and the community concession (CC) theory. The PAE argues that as private ownership is the full control of a property, it provides the good’s owner with incentives to protect the environment. Therefore, the shared common property could also be a type of private property.

On the other hand, the CC theory emphasizes the importance of empirical studies on how the community arrangements solve environmental-related problems [19,34]. Due to CC theory, community arrangements can turn conflicts into potential opportunities for both parties to solve the existing environmental issues by win-win games. The Hardinian “tragedy of the commons” could be solved.

The Guatemalan CC case that we have analyzed in this paper matches the traditional public-good scenario CC. Due to the Guatemalan state Forest Law [40], the forest concession is defined as an usufruct through which the state authorizes the use of its partial territories to an individual, a company, or a community, part of its territory. Therefore, in our paper, forest concessions are considered usufructs for community use. It is not the traditional privatization to an individual or an enterprise, but a kind of rent for the local community, aiming to include the community in the sustainable management of the resource. In this regard, we consider that the current Guatemalan forest concession is a transitional step towards a jointly owned private property. Table 3 below summarizes the political institutions, forest policies, and communities’ wood arrangements in Guatemala. It shows that both the traditional indigenous settled department Totonicapán and the modern community concessions in RBM have efficiently conducted forest preservation.

Table 3.

Political institutions, forest policies, and communities’ forest arrangements in Guatemala.

5. Discussion and Proposals

The above analysis has shown the successful application of the community concession in protecting the Guatemalan forest and its sustainability. However, we consider that several aspects should be discussed and could be applied for further theoretical and empirical studies.

First, it is necessary to synthesize further the PAE criteria and the CC theory to make their application clear. Some of the traditional private property rights theories criticize the community concession approach as it seems the latter one is not a pure private property solution [12]. It is admitted that the CC criteria do not conduct traditional privatization when environmental issues are considered. However, given that entrepreneurship is the driving force of the market economy, both the communities and firms could take more initiatives when making decisions for the benefit or profit of their own organization under the community concession solution. The theoretical proposal also cooperates with the empirical results that our paper deal with, as two firms have participated in the concessions successfully.

We consider that the CC theory can help create a better community or firm-level decision-making process by respecting private property rights. In contrast, a further release of property titles to the community and firms in the mid-run would improve forest and environmental protection. This argumentation is based on the three principles of PAE theory that we have shown in Section 2.1, as Wang et al. argued [8]. The first is the impossibility of economic calculation through centrally planned government policy. The exact identification of private property rights gives the property owner the incentive to protect the environment in which he lives and sue anyone who violates his property’s environment. In contrast, the lack of private property generates the tragedy of the commons, and the environment is polluted without the incentive to protect it [13,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Therefore, as the state still holds the property titles of the forest or the land, they can legitimately intervene in the decision-making of the local communities and firms, making economic calculation impossible and revere the current result of forest and land preservation. Furthermore, as the state owns property titles, they could nationalize the woods or the land easier than conducting the policy under a pure private property right criterion. This result could prevent economic calculation and undermines entrepreneurship [15]. State ownership could still create a zero-sum scenario when the state wants to intervene in the local arrangements [15,30,31,32]. Conflicts might be solved by voluntary negotiations. However, state legislation might cause the unexpected “one party wins, and the other loses” consequence.

Secondly, based on the PAE principles, community arrangements could also be privately owned under a pure private property scenario. Furthermore, full protection and respect for private property rights will allow communities to compete with each other fairly and avoid cronyism, providing better forest protection and output mechanisms through market mechanisms. In this regard, further privatization of the existing state-title-based concession does not change the right of use but strengthens the private ownership. Therefore, the theoretical research needs to be further deepened, as the conflict between existing theories (the PAE and the CC) is not enough to provide better theoretical support for the announcement policy.

Thirdly, relevant empirical research should also be strengthened. We believe that further empirical research is reflected in the following aspects. (1) Our paper shows that the community concession policy has helped Guatemala conduct better forest conservation since the middle 1990s when the policy was adopted. However, the policy has not been applied in the rest of the country’s territories. The research on related policies should be deepened for the current community concessions. These policies should include a detailed analysis of state-interventionist policies and the community concessions. Our study only proposes a preliminary direction for policy research related to Guatemala, and the specific content must be deepened in future research. (2) The relevant empirical research should be extended to a broader range of countries, especially developing regions. Given the different economic conditions faced by developing countries and the characteristics of developing countries, it is necessary to examine the specific economic conditions of various developing countries and their gains and losses in forest and land protection policies separately.

Finally, it is both theoretically and empirically important to discuss how to understand the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) from the PAE-CC criteria, as it is an essential theoretical foundation for much previous mainstream environmental research [67,68,69]. The EKC argues that economic development initially detorts the environment while the society later perceives the importance of ecological protection, stating to reduce environmental degradation [70]. Although it is unnecessary to start protecting the environment after it has been polluted by human beings, whether the PAE-CC criteria could contribute to and modify the EKC to benefit further environmental economics studies remains a question. In the cases of Guatemala and other developing countries, it is necessary to study how to avoid environmental and forest degradation even when these countries start their initial steps of economic development. In this regard, the PAE-CC criteria can benefit the related research.

6. Conclusions

Based on the private property-rights approach environmentalist theory and the community concession theory, this paper discusses how community concessions (both local executive communities and private firms) as usufructs in RBM of Guatemala partially effectively conducted forest preservation. Previously, research studied how the traditional indigenous communities in Totonicapán have successfully conducted forest preservation. Our study extends the scope to Guatemala’s modern and democratic municipals’ forest preservation. Our empirical results show that the 11 in-force concessions in RBM had only 0.024% forest deforestation in recent years, which was the lowest rate in the whole country (while deforestation in Guatemala was at a rate of 1.2%) [65]. Due to the Forest Law [40] and the CONAP report [66], this deforestation rate shows that these concessions, compared with the general forest condition in Guatemala and other areas of the RBM, have reached the Guatemalan state’s requirements of reducing forest degradation and conserving the country’s forest ecosystems. However, due to the lack of data, there have been no other quantitative result to show the specific economic benefits that each concession can bring about. This vacancy should be the scope analysis of further research.

The concession arrangements also have generated business, and the sustainable use of the forest has also increased. It has generated some 58 million USD through 111 small and medium companies employing 8800 individuals [65]. Yet, as the accessible data are limited currently, we suggest that it is necessary to conduct more detailed quantitative studies on the Guatemalan forest concession arrangements. In contrast, the Guatemalan government should provide more transparency on forest data issues.

On the theoretical side, our research reckons that community property as a shared good could also be treated as a common private property if the owners could have full control of it. However, the Guatemalan forest concession arrangements are just usufructs, which means the state still owns the property. Therefore, the current Guatemalan forest concession arrangement is just a third way: neither traditional private ownership nor the state’s full planning of forest preservation. We argue that state ownership could reverse the result of the current and limited decentralized forest reform. As the state still holds the property titles of the forest or the land, they can legitimately intervene in the decision-making of the local communities and firms, making economic calculation impossible and revere the current result of forest and land preservation. Furthermore, as the state owns property titles, they could nationalize the woods or the land easier than conducting the policy under a pure private property right criterion. In this regard, we suggest that Guatemala state should privatize all of these forests to the current concessions’ communities and firms. If the results are positive, we propose the Guatemalan government further apply the decentralization forest policy to the whole country.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.F.L. and S.F.O.; methodology, E.F.L., S.F.O. and W.H.W.; software, E.F.L., S.F.O. and W.H.W.; validation E.F.L. and W.H.W.; formal analysis, E.F.L., S.F.O. and W.H.W.; investigation, E.F.L., S.F.O. and W.H.W.; resources, E.F.L., S.F.O. and W.H.W.; data curation, E.F.L., S.F.O. and W.H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, E.F.L. and S.F.O.; writing—review and editing, E.F.L., S.F.O. and W.H.W.; visualization, W.H.W.; supervision, E.F.L. and W.H.W.; project administration, W.H.W.; funding acquisition, W.H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Instituto de Estudios Políticos y Relaciones Internacionales at the Francisco Marroquin University funded this project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on the study by Wang et al. [8] on free-market environmentalism. We gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments of Guillermo Rodriquez del Valls and the three anonymous referees. Any remaining errors are the responsibility of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Huntington, S.P. Democracy’s third wave. J. Democr. 1991, 2, 12–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbsen de Maldonado, K. Guatemala: Danzando con las crisis económica y política. Rev. Cienc. Política 2010, 30, 335–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzalejos, J.; Fernández Luiña, E. América Latina: Una Agenda de Libertad 2018; FAES—Fundación para el Análisis y los Estudios Sociales: Madrid, Spain, 2018; ISBN 8492561424. [Google Scholar]

- PNUD. Informe de Desarrollo Humano Guatemala. Available online: https://desarrollohumano.org.gt/desarrollo-humano/calculo-de-idh/ (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Marroquín Gramajo, A.; Noel Alfaro, L. Protestant Ethic and Prosperity: Vegetable Production in Almolonga, Guatemala. In Political Economy, Neoliberalism, and the Prehistoric Economies of Latin America; Matejowsky, T., Wood, D.C., Eds.; Research in Economic Anthropology; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2012; Volume 32, pp. 85–107. ISBN 978-1-78190-059-8. [Google Scholar]

- Latinobaromero. Available online: http://www.latinobarometro.org/latOnline.jsp (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Azpuru, D.; Mariana, R.; Zechmeister, E. Cultura Política de la Democracia en Guatemala y en las Américas 2016–2017. Un Estudio Comparado sobre Democracia y Gobernabilidad; Instituto de Estudios Peruanos: Jesus Maria, Peru, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.H.; Moreno-Casas, V.; de Soto, J. A free-market environmentalist transition toward renewable energy: The cases of Germany, Denmark, and the United Kingdom. Energies 2021, 14, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Mises, L. Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis; Liberty Fund: Carmel, IN, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hayek, F.A. The use of knowledge in society. Am. Econ. Rev. 1945, 35, 519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta de Soto, J. Socialism, Economic Calculation and Entrepreneurship; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Block, W. Environmentalism and economic freedom: The case for private property rights. J. Bus. Ethics 1998, 17, 1887–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.L.; Baden, J.; Block, W.; Borcherding, T.; Chant, J.; Dolan, E.; Mc Fetridge, D.; Rothbard, M.N.; Smith, D.; Shaw, J.; et al. Economics and the Environment: A Reconciliation; Block, W., Ed.; The Fraser Institute: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.L.; Leal, D.R. Free Market Environmentalism; Revised Edition; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta de Soto, J. Entrepreneurship and the Theory of Free Market Environmentalism. In The Theory of Dynamic Efficiency; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cordato, R. Toward an Austrian theory of environmental economics. Q. J. Austrian Econ. 2004, 7, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.L. Resourceship: An Austrian theory of mineral resources. Rev. Austrian Econ. 2007, 20, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, V. Polycentricity; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rothbard, M.N. Law, property rights, and air pollution. Cato J. 1982, 2, 55–99. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, P. Monarchy, democracy and private property order how human rights have been violated and how to protect them a response to Hans H. Hoppe, F. A. Hayek, and Elinor Ostrom. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2019, 16, 177–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, E.W. The non-aggression principle: A short history. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2019, 16, 31–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, P. An Austrian school view on Eucken’s ordoliberalism. Analyzing the roots and concept of German ordoliberalism from the perspective of Austrian school economics. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2020, 17, 13–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, V.I.; Wang, W.H.; Zhu, H. Israel kirzner on dynamic efficiency and economic development. Procesos Merc. Rev. Eur. Econ. Política 2020, 17, 283–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämpe, J. Individual secession and extraterritoriality. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2013, 10, 195–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, H.-H. A realistic libertarianism. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2015, 12, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Mises, L. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics; Ludwig von Mises Institute: Auburn, AL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J.; Klein, P.G. Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment: A New Approach to the Firm; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; ISBN 9781139021173. [Google Scholar]

- Merino, J.B. Teoría del intercambio. Propuesta de una nueva teoría de los cambios interpersonales basada en tres elementos más simples. Rev. Procesos Merc. 2015, 12, 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettke, P.J.; Coyne, C.J.; Leeson, P.T. Institutional stickiness and the new development economics. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2008, 67, 331–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boettke, P. Economics and public administration. South. Econ. J. 2018, 84, 938–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettke, P. Is the only form of ‘reasonable regulation’ self regulation?: Lessons from Lin Ostrom on regulating the commons and cultivating citizens. Public Choice 2010, 143, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tabarrok, A. Elinor Ostrom and the Well-Governed Commons. Available online: https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2009/10/elinor-ostrom-and-the-wellgoverned-commons.html (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Elinor, O. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Background on the institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, H. Extensions of “The Tragedy of the Commons”. Science 1998, 280, 682–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Block, W.; Jankovic, I. Tragedy of the partnership: A critique of Elinor Ostrom. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2016, 75, 289–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 9781400831739. [Google Scholar]

- El Congreso de la República de Guatemala. Ley Forestal. 1996. Available online: http://www.sice.oas.org/investment/natleg/gtm/forestal_s.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Pawar, K.V.; Rothkar, R.V. Forest conservation & environmental awareness. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 11, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- General Multilingual Environment Thesaurus Forest Protection. Available online: https://www.eionet.europa.eu/gemet/en/concept/10706 (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegida. Monitoreo de la Gobernabilidad en la Reserva de la Biosfera Maya; Gobierno de la Republica de Guatemala: Guatemala, Guatemala, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature Deforestation and Forest Degradation. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/deforestation-and-forest-degradation (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Pacheco, P.; Ibarra, E.; Cronkleton, P.; Amaral, P. Políticas Públicas que Afectan el Manejo Forestal Comunitario. In Manejo Forestal Comunitario en América Latina: Experiencia, Lecciones Aprendidas y Retos Para el Futuro; Centro para la Investigación Forestal (CIFOR): Bogor Barat, Indonesia, 2008; pp. 201–230. [Google Scholar]

- Veblen, T.T. Forest preservation in the western highlands of Guatemala. Geogr. Rev. 1978, 68, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, K. Contextual vulnerability of the communal forests and population of Totonicapán, Guatemala. Espac. Desarro. 2018, 31, 117–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elías, S.; Wittman, H. State, Forest and Community: Decentralization of forest administration in Guatemala. In The Politics of Decentralization: Forests, Power, and People; Colfer, C.J.P., Capistrano, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 282–295. ISBN 9781138995109. [Google Scholar]

- Congreso de la República. Ley General de Descentralización; El Congreso de la República de Guatemala: Guatemala, Guatemala, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Congreso de la República. El Código Municipal; El Congreso de la República de Guatemala: Guatemala, Guatemala, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Elías, S. From communal forests to protected areas. Conserv. Soc. 2012, 10, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittman, H.; Geisler, C. Negotiating locality: Decentralization and communal forest management in the Guatemalan highlands. Hum. Organ. 2005, 64, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, P.M.E.; Evans, T.; Andersson, K.; Castellanos, E. Decentralization, forest management, and forest conditions in Guatemala. J. Land Use Sci. 2015, 10, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.P. Communal forests, political spaces: Territorial competition between common property institutions and the state in Guatemala. Sp. Polity 2002, 6, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constitución Política de la República. Constitución Política de la República; El Tribunal Constitucional de Guatemala: Guatemala, Guatemala, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Garoz, B.; Gauster, S.; Sigüenza, P.; Dür, J. Algunas Implicaciones e la Concentración de la Tierra para la Gestión de los Recursos Naturales y el Territorio de Guatemala. In Territorios; Instituto de Estudios Agrarios y Rurales: Guatemala, Guatemala, 2006; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Transparencia Forestal. 2012. Available online: http://www.transparenciaforestal.info/background/forest-transparency/33/la-medici-n-de-la-transparencia-del-sector-forestal (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Gleijeses, P. Shattered Hope: The Guatemalan Revolution and the United States, 1944–1954; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1991; ISBN 0691025568. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Rivas, E. Revoluciones sin Cambios Revolucionarios; F&G editores: Guatemala, Guatemala, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bank, W. Republic of Guatemala Country Environmental Analysis: Addressing the Environmental Aspects of Trade and Infrastructure Expansion; The World bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Huertas, I.A.G. Gestión Colectiva y su Incidencia en la Conservación y Utilización del Bosque Comunal, Parcialidad Baxquiax, Cantón Juchanep, Municipio de Totonicapán, Totonicapán. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala, Guatemala, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ixíu, A. Totonicapán, un Bosque. Plaza Pública. 2013. Available online: https://www.plazapublica.com.gt/content/un-bosque (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Gamazo, A.C. Totonicapán. El Poder Político de un Bosque. 7K. 2016. Available online: https://www.naiz.eus/en/hemeroteca/7k/editions/7k_ (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- López, R.T.; Hierro, P.G. Los Bosques Comunales de Totonicapán: Historia, Situación Jurídica y Derechos Indígenas; Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO-Guatemala): Guatemala, Guatemala, 2002; Volume 4, ISBN 9992266600. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, Ó.E. Concesiones Forestales Comunitarias–Experiencia Petén; ACOFOP: Guatemala, Guatemala, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas. Available online: https://www.conap.gob.gt/ (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Ferrari, M. Environmental policy stringency, technical progress and pollution haven hypothesis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, A.; Busato, F. Energy vulnerability around the world: The global energy vulnerability index (GEVI). J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 118691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Gatto, A. The puzzle of greenhouse gas footprints of oil abundance. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2021, 75, 100936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznets, S. Economic growth and income inequality. Am. Econ. Rev. 1955, 45, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).