Perception of the Impacts of Tourism by the Administrations of Protected Areas and Sustainable Tourism (Un)Development in Slovakia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Environmental Impacts of Tourism

2.2. Social Impacts of Tourism

2.3. Economic Impacts of Tourism

3. Materials and Methods

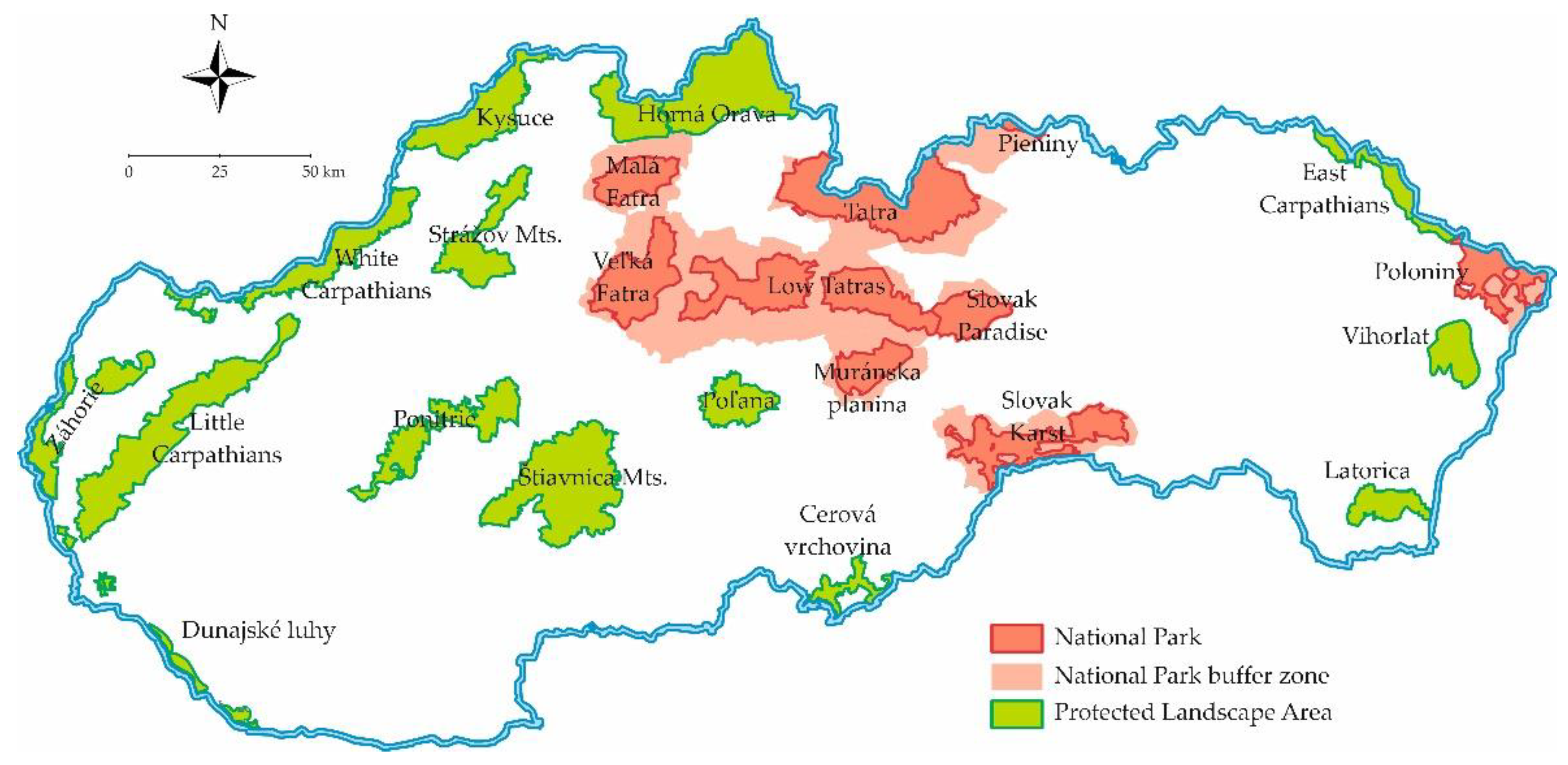

3.1. Nature Protection in Slovakia

3.2. Data Collection

- Tourism protects and preserves the natural and cultural heritage. (En1);

- Tourism increases the aesthetic value of the area. (En2);

- Tourism educates and interprets the values of natural and cultural heritage to visitors. (En3);

- Tourism informs local people about the value of natural and cultural heritage. (En4);

- Tourism provides greater care for the environment. (En5);

- Tourism reduces the diversity of flora and fauna. (En6);

- Tourism disrupts and destroys natural habitats. (En7);

- Tourism causes a conflict of interest in doing business using natural resources. (En8);

- Tourism decreases water and air quality. (En9);

- Tourism increases noise level. (En10);

- Tourism causes an increase in soil erosion. (En11);

- Tourism increases waste production. (En12);

- Tourism causes traffic congestion. (En13);

- Tourism causes the loss of natural landscape and agricultural land. (En14)

- Tourism creates new job opportunities. (Ec1);

- Tourism reduces the migration of local people. (Ec2);

- Tourism is an opportunity to engage in the entrepreneurial activities of local people. (Ec3);

- Tourism supports the development of crafts and local production of goods. (Ec4);

- Tourism supports protected areas with funds. (Ec5);

- Tourism uses the local workforce and its expertise. (Ec6);

- Tourism stimulates investment in public and civic infrastructure. (Ec7);

- Tourism improves the quality of life of local people. (Ec8);

- Tourism increases the cost of living of local people. (Ec9);

- Tourism causes leakage of profits outside the region. (Ec10);

- Tourism increases the cost of road maintenance, the transport system, and additional infrastructure. (Ec11);

- Tourism increases people’s participation in local development. (Ec12);

- Tourism contributes to the preservation of local traditions and customs. (S1);

- Tourism builds local patriotism. (S2);

- Tourism changes the image of the region into a more attractive one. (S3);

- Tourism displaces local people in favor of tourism development. (S4);

- Tourism causes stress to locals. (S5);

- Tourism reduces the cohesion of local communities. (S6);

- Tourism increases the interest of locals mainly in the economic perspective compared to the protection of the area. (S7);

3.3. Data Processing and Analysis

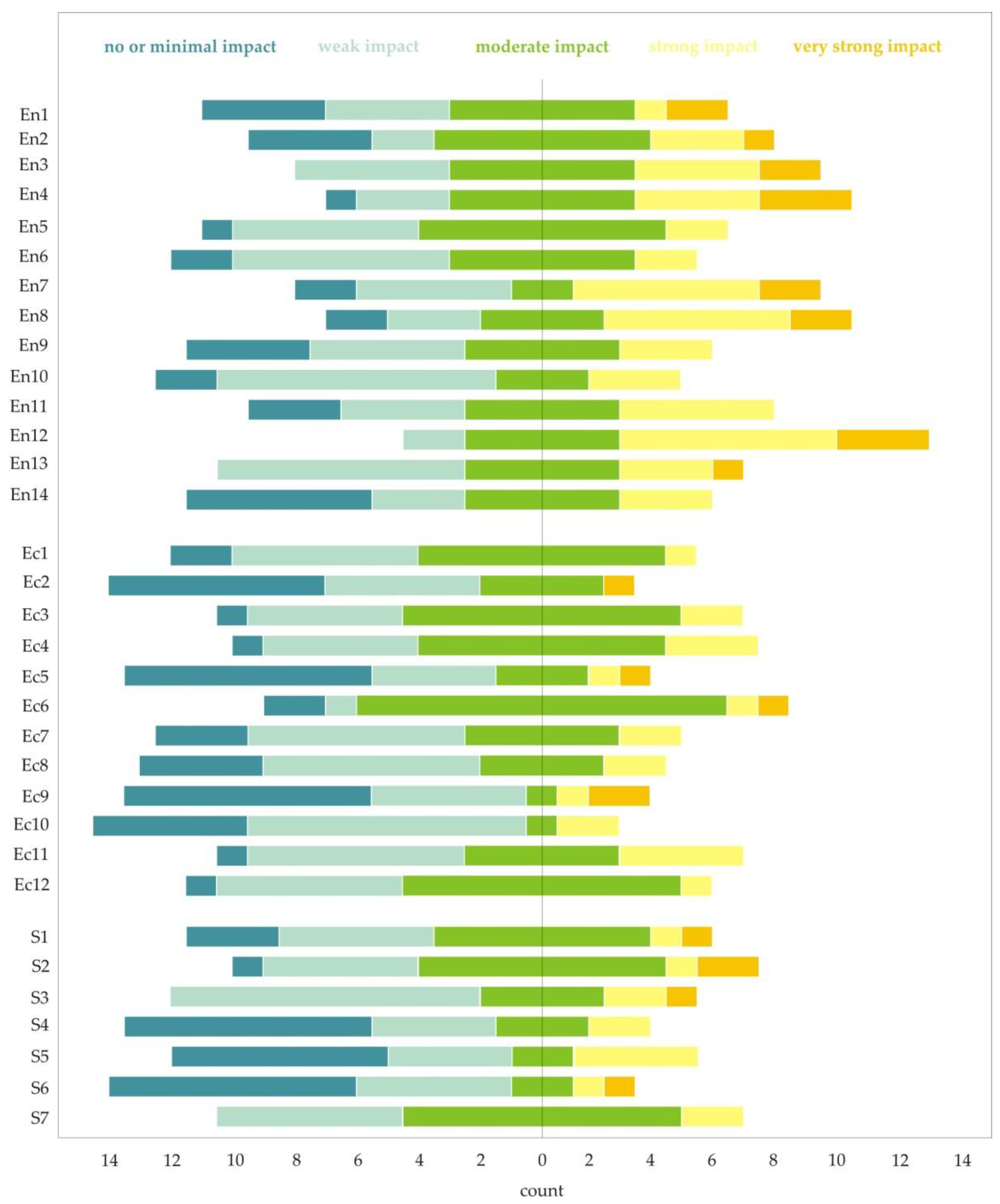

4. Results and Discussion

- Increase in waste production (88%);

- Informing local people about the value of the natural and cultural heritage (76%);

- Education and interpretation of the values of natural and cultural heritage to visitors (71%);

- Causing a conflict of interest in doing business using natural resources (71%);

- Disruption and destruction of natural habitats (59%).

- Tourism causes a leakage of profits outside the region (18%);

- Tourism reduces the cohesion of local communities (24%);

- Tourism displaces local people in favor of tourism development (29%);

- Tourism supports protected areas with funding (29%);

- Tourism reduces local migration (29%).

- Tourism causes traffic congestion;

- Tourism causes a leakage of profits outside the region;

- Tourism increases the cost of road maintenance, transport systems, and additional infrastructure;

- Tourism displaces local people in favor of tourism development.

- -

- use of the natural heritage as an educational and training tool in geological and environmental sciences for the broadest parts of society;

- -

- contribute to the sustainable development of the territory and its immediate surroundings;

- -

- ensure an appropriate level of protection and preservation of the geopark content for future generations.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Budkowski, G. Tourism and environmental conservation: Conflict, coexistence, or symbiosis? Environ. Conserv. 1976, 3, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romeril, R. Tourism and the environment: Towards a symbiotic relationship. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 1985, 25, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, P. Nie je ochrana ako ochrana. Alebo všetkého veľa škodí. In Príroda a Jej Ochrana v Priereze Času, Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference, Liptovský Mikuláš, Slovakia, 17–19 October 2017; Klinda, J., Žažová, H., Eds.; Slovenské múzeum ochrany prírody a jaskyniarstva: Liptovský Mikuláš, Slovakia, 2018; pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ložek, V. Dusledky poznání vývoje přírody a krajiny ČR v holocénu pro ochranu přírody. In Ochrana Přírody a Krajiny v ČR; Machar, I., Drobilová, L., Eds.; Palacký University Olomouc: Olomouc, Czech Republic, 2012; pp. 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zweckbronner, G. Mensch, Natur, Maschine im Spegeldreier Jahrhundert wenden. In Príroda a Jej Ochrana v Priereze Času, Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference, Liptovský Mikuláš, Slovakia, 17–19 October 2017; Urban, P., Ed.; Slovenské múzeum ochrany prírody a jaskyniarstva: Liptovský Mikuláš, Slovakia, 2000; pp. 84–85. [Google Scholar]

- The Benefits of Natural World Heritage: Identifying and Assessing Ecosystem Services and Benefits Provided by the World’s Most Iconic Natural Places. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2014-045.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2022).

- Buckley, R. Ecological indicators of tourist impacts in parks. J. Ecotour. 2003, 2, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eagles, P.F.J.; McCool, S.F.; Haynes, C.D. Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas: Guidelines for Planing and Management; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Spenceley, A.; Snyman, S.; Eagles, P.F.J. Guidelines for Tourism Partnerships and Concessions for Protected Areas: Generating Sustainable Revenues for Conservation and Development; Report to the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity and IUCN; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.cbd.int/tourism/doc/tourism-partnerships-protected-areas-web.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Koncul, N. Environmental Issues and Tourism. Ekonomska Misao i Praksa 2007, 2, 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, R.E.; Anderson, L.E.; Pettengill, P. Managing Outdoor Recreation: Case Studies in the National Parks; CABI: Cambrige, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalič, T. Environmental Management of a Tourist Destination. A Factor of Tourism Competitiveness. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolvanen, A.; Kangas, K. Tourism, biodiversity and protected areas—Review from northern Fennoscandia. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 169, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, D. Tourism and the Less Developed Countries; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hillery, M.; Nancarrow, B.; Griffin, G.; Syme, G. Tourist perception of environmental impact. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 853–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.-F.; Spenceley, A.; Hvenegaard, G.; Buckley, R.; Groves, C. Tourism and Visitor Management in Protected Areas; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- GhulamRabbany, M.; Afrin, S.; Rahman, A.; Islam, F.; Hoque, F. Environmental effects of tourism. Am. J. Environ. Energy Power Res. 2013, 1, 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Lew, A.A. A framework of tourist attraction research. Ann. Tour. Res. 1987, 14, 553–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhanna, E. Sustainable Tourism Development and Environmental Management for Developing Countries. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2006, 4, 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R.; Pannell, J. Environmental impacts of tourism and recreation in national parks and conservation reserves. J. Tour. Stud. 1990, 1, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Plesník, J. Kategorie Mezinárodní unie na ochranu přírody pro chráněná území: Možnosti jejich turistického využit. Ochrana Přírody 2010. Available online: https://www.casopis.ochranaprirody.cz/zvlastni-cislo/kategorie-mezinarodni-unie-na-ochranu-prirody-pro-chranena-uzemi/ (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Rodríguez-López, N.; Diéguez-Castrillón, M.I.; Gueimonde-Canto, A. Sustainability and Tourism Competitiveness in Protected Areas: State of Art and Future Lines of Research. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhammar, H.; Li, W.; Molina, C.M.M.; Hickey, V.; Pendry, J.; Narain, U. Framework for Sustainable Recovery of Tourism in Protected Areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsoy, J.; Korir, J.; Yego, J. Environmental Impacts of Tourism in Protected Areas. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2012, 2, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pásková, M. Environmentalistika cestovního ruchu (Tourism Environmentalism). Czech J. Tour. 2012, 2, 77–113. [Google Scholar]

- Inskeep, E. Tourism Planning: An Integrated and Sustainable Development Approach; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mieczkowski, Z. Environmental Issues of Tourism and Recreation; University Press of America: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, V.T.C. Sustainable tourism: A marketing perspective. In Tourism Sustainability: Principles to Practice; Stabler, M.J., Ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1997; pp. 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, C.P. Social impact assessment: The state of the art updated. SIA Newsl. 1977, 29, 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Sheldon, P.; Var, T. Resident Perception of the Environmental Impacts of Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1987, 14, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, R.; Long, P.T.; Gustke, L.D. The effect of tourism development on objective indicators of local quality of life. In Tourism: Building Credibility for a Credible Industry, Proceedings of the 22nd Annual TTRA Conference, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–13 June 1991; Travel and Tourism Research Association: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 1991; pp. 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Lankford, S.V.; Howard, D.R. Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurowski, C.; Uysal, M.; Williams, D.R. A Theoretical Analysis of Host Community Resident Reactions to Tourism. J. Travel Reserach 1997, 36, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.; Vogt, C. The Relationship between Residents’ Attitudes toward Tourism and Tourism Development Options. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.K.; Masud, M.M.; Akhtar, R.; Hossain, M.M. Impact of community participation on sustainable development of marine protected areas: Assessment of ecotourism development. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M. A study on the actual conditions of Korean outbound tourism and recommendations for its improvements. Study Tour. 1993, 17. Available online: https://scholar.google.sk/scholar?hl=sk&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=A+study+on+the+actual+conditions+of+Korean+outbound+tourism+and+recommendations+for+its+improvements&btnG= (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Ap, J.; Crompton, J. Residents’ Strategies for Responding to Tourism Impacts. J. Travel Res. 1993, 32, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, S.; Martin, S. Community Attachment and Attitudes Towards Tourism Development. J. Travel Res. 1994, 32, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T.; Kuščer, K. Can overtourism be managed? Destination management factors affecting residents’ irritation and quality of life. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lickorish, L.J.; Jefferson, A.; Bodlener, J.; Jenkins, C.L. Developing Tourism Destinations—Policies and Perspectives; Longman: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C. Recreation Tourism—A Social Science Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D. Impacts of Tourism on Residents’ Leisure: Concepts and a Longitudinal Case Study of Spey Valley, Scotland. J. Tour. Stud. 1993, 4, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, G.; Williams, A.M. Critical Issues in Tourism: A Geographical Perspective; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pásková, M. Udržitelnost Rozvoje Cestovního Ruchu; Gaudeamus: Hradec Králové, Czech Republic, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Doxey, G.V. A causation theory of visitor-resident irritants: Methodology and research inferences. In The Impact of Tourism: Sixth Annual Conference Proceedings of the Travel Research Association; TTRA: San Diego, CA, USA, 1975; pp. 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Telfer, D.J.; Sharpley, R. Tourism and Development in the Developing World; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.; Ashley, C. Tourism and Poverty Reduction: Pathways to Prosperity; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Obradović, S.; Tešin, A.; Milošević, D. Residents’ perceptions of and satisfaction with tourism development: A case study of the Uvac Special Nature Reserve, Serbia. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 21, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunt, P.; Courtney, P. Host Perceptions of Sociocultural Impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 493–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks for Biodiversity: Policy Guidance Based on Experience in ACP Countries; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1999.

- Beaumont, N. Ecotourism and the Conservation Ethic: Recruiting the Uninitiated or Preaching to the Converted? J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 317–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeppel, H.; Muloin, S. Conservation Benefits of Interpretation on Marine Wildlife Tours. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2008, 13, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, P.L.; Selin, S.; Cerveny, L.; Bricker, K. Outdoor Recreation, Nature-Based Tourism, and Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perdue, R.; Long, P.; Allen, L. Resident Support for Tourism Development. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.; Clark, M. An Exploratory Examination of Urban Tourism Impact, with Reference to Residents Attitudes in the Cities of Canterbury and Guildford. Cities 1997, 14, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Nyaupane, G.P. Exploring the nature of tourism and quality of life perceptions among residents. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comerio, N.; Strozzi, F. Tourism and its economic impact: A literature review using bibliometric tools. Tour. Econ. 2019, 25, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.R.; Hafer, H.R.; Long, P.T.; Perdue, R.R. Rural residents’ attitude toward recreation and tourism development. J. Travel Res. 1993, 31, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, R. Community-driven tourism planning and residents’ preferences. Tour. Manag. 1993, 14, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, C. Host perceptions of impacts: A comparative tourism study. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.; Lawton, L. Resident perceptions in the urban-rural fringe. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 349–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapper, R.; Cochrane, J. Forging Links between Protected Areas and the Tourism Sector: How Tourism Can Benefit Conservation; UNEP: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.D.; Snepenger, D.J.; Akis, S. Residents’ perceptions of tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korca, P. Resident attitudes toward tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 695–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C.A.; Stronza, A. Stage-based tourism models and resident attitudes towards tourism in an emerging destination in the developing world. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act No. 543/2002 Coll. on Nature and Landscape Protection. Available online: https://www.zakonypreludi.sk/zz/2002-543 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- State Nature Conservancy. Prehľad Chránených Území Národnej Sústavy k 31. 12. 2021. Available online: http://www.sopsr.sk/news/file/prehlady-2022/Prehlady_CHU_k_31._12._2021%20-%20b.doc (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Škodová, M.; Mazúrek, J. Chránené Územia Slovenska; Faculty of Natural Sciences, Matej Bel University in Banská Bystrica: Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vološčuk, I.; Švajda, J. Ohrozenie Prírodných Systémov a Vývoj Koncepcií Ochrany Prírody. Monografické Štúdie o Národných Parkoch; Vydavateľstvo Technickej Univerzity vo Zvolene: Zvolen, Slovakia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Plesník, J. Chráněná území: Přerůstá skutečně kvantita v kvalitu? Ochrana Přírody. 2008. Available online: https://www.casopis.ochranaprirody.cz/mezinarodni-ochrana-prirody/chranena-uzemi/ (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Kozel, R.; Mynářová, L.; Svobodová, H. Moderní Metody a Techniky Marketingového Výzkumu; GRADA Publishing: Prague, Czech Republic, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 22, 140–155. [Google Scholar]

- Sahai, H.; Ageel, M.I. The Analysis of Variance: Fixed, Random and Mixed Models; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Canteiro, M.; Córdova-Tapia, F.; Brazeiro, A. Tourism impact assessment: A tool to evaluate the environmental impacts of touristic activities in Natural Protected Areas. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviano, M.; Di Nauta, P.; Montella, M.M.; Sciarelli, F. The Cultural Value of Protected Areas as Models of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- D’Arco, M.; Lo Presti, L.; Marino, V.; Maggiore, G. Is sustainable tourism a goal that came true? The Italian experience of the Cilento and Vallo di Diano National Park. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Conservation implications of COVID-19: Effects via tourism and extractive industries. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 247, 108640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiezik, M.; Niňajová, I.; Švajda, J.; Elexová, Ľ. Koncept Prírodného Turizmu v Slovenských Podmienkach; Aevis: Snina, Slovakia, 2019; Available online: https://www.aevis.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/koncept_prirodneho_turizmu_v2_final-1.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Job, H.; Mayer, M. Forstwirtschaft versus Waldnaturschutz: Regionalwirtschaftliche Opportunitätskosten des Nationalparks Bayerischer Wald. Allg. Forst Und Jagdztg. 2012, 183, 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Job, H.; Mayer, M.; Woltering, M.; Müller, M.; Harrer, B.; Metzler, D. The Regional Economic Impact of Bavarian Forest National Park; Nationalparkverwaltung Bayerischer Wald: Gragenau, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andries, D.M.; Arnaiz-Schmitz, C.; Díaz-Rodríguez, P.; Herrero-Jáuregui, C.; Schmitz, M.F. Sustainable Tourism and Natural Protected Areas: Exploring Local Population Perceptions in a Post-Conflict Scenario. Land 2021, 10, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinner, J.; Fuentes, M.M.; Randriamahazo, H. Exploring social resilience in Madagascar’s marine protected areas. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nyaupane, G.P.; Poudel, S. Linkages among biodiversity, livelihood, and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1344–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.T.; Nyaupane, G.P. Protected areas, wildlife-based community tourism and community livelihoods dynamics: Spiraling up and down of community capitals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development (accessed on 9 April 2022).

- Flores, M.P.; Parra, M.C. Indicadores de capacidad de carga del turismo. TuryDes Rev. De Investig. En Tur. Y Desarro. Local 2010, 3. Available online: https://www.eumed.net/rev/turydes/08/fapm.htm (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Maldonado-Oré, E.M.; Custodio, M. Visitor environmental impact on protected natural areas: An evaluation of the Huaytapallana Regional Conservation Area in Peru. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 31, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transport, Construction and Regional Development of the Slovak Republic. Stratégia Rozvoja Cestovného Ruchu do Roku. 2020. Available online: https://www.mindop.sk/ministerstvo-1/cestovny-ruch-7/legislativa-a-koncepcne-dokumenty/koncepcne-dokumenty/strategia-rozvoja-cestovneho-ruchu-do-roku-2020 (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Carpathian Convention. Available online: http://www.carpathianconvention.org/ (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Hsu, C.-H.; Lin, H.-H.; Jhang, S. Sustainable Tourism Development in Protected Areas of Rivers and Water Sources: A Case Study of Jiuqu Stream in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Yang, Z.; Gao, H.; Tao, H.; Xu, M. Does PPP Matter to Sustainable Tourism Development? An Analysis of the Spatial Effect of the Tourism PPP Policy in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Matteis, F.; Notaristefano, G.; Bianchi, P. Public—Private Partnership Governance for Accessible Tourism in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). Sustainability 2021, 13, 8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gúčik, M.; Gajdošík, T.; Lencséosová, Z. Udržateľný cestovný ruch. In 5. Mezinárodní Kolokvium o Cestovním Ruchu; Holešinská, A., Ed.; Masaryk University: Brno, Czech Republic, 2014; pp. 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zamfir, A.; Corbos, R.-A. Towards Sustainable Tourism Development in Urban Areas: Case Study on Bucharest as Tourist Destination. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12709–12722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanguay, G.A.; Rajaonson, J.; Therrien, M.C. Sustainable Tourism Indicators: Selection Criteria for Policy Implementation and Scientific Recognition. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 862–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Šaparnienė, D.; Mejerė, O.; Raišutienė, J.; Juknevičienė, V.; Rupulevičienė, R. Expression of Behavior and Attitudes toward Sustainable Tourism in the Youth Population: A Search for Statistical Types. Sustainability 2022, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Zhen, S.; Mei, L.; Jiang, H. Ecotourism Practices in Potatso National Park from the Perspective of Tourists: Assessment and Developing Contradictions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinello, S.; Butturi, M.A.; Gamberini, R.; Martini, U. Indicators for sustainable touristic destinations: A critical review. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, in press. [CrossRef]

| Protected Area | Tourism Form | Environmental Impacts | Social Impacts | Economic Impacts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| Malá Fatra NP | hard | 2/5 | 8/9 | 2/4 | 4/4 | 4/8 | 3/3 |

| Slovak Karst NP | soft | 4/5 | 4/9 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 3/8 | 0/3 |

| Pieniny NP | hard | 5/5 | 8/9 | 2/4 | 2/4 | 5/8 | 2/3 |

| Veľká Fatra NP | soft | 3/5 | 3/9 | 4/4 | 1/4 | 6/8 | 1/3 |

| Nízke Tatry NP | hard | 4/5 | 9/9 | 4/4 | 3/4 | 6/8 | 2/3 |

| Tatra NP | hard | 2/5 | 6/9 | 2/4 | 3/4 | 3/8 | 2/3 |

| Eastern Carpathians PLA | soft | 3/5 | 7/9 | 1/4 | 1/4 | 3/8 | 0/3 |

| Horná Orava PLA | hard/soft | 4/5 | 9/9 | 3/4 | 2/4 | 8/8 | 1/3 |

| Vihorlat PLA | soft | 3/5 | 4/9 | 2/4 | 1/4 | 1/8 | 0/3 |

| Latorica PLA | soft | 3/5 | 2/9 | 3/4 | 1/4 | 4/8 | 1/3 |

| Záhorie PLA | soft | 0/5 | 1/9 | 4/4 | 1/4 | 4/8 | 0/3 |

| Poľana PLA | soft | 0/5 | 1/9 | 2/4 | 1/4 | 1/8 | 1/3 |

| Biele Karpaty PLA | soft | 5/5 | 3/9 | 4/4 | 2/4 | 7/8 | 2/3 |

| Kysuce PLA | soft | 3/5 | 5/9 | 1/4 | 0/4 | 3/8 | 0/3 |

| Ponitrie PLA | hard | 5/5 | 5/9 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/8 | 1/3 |

| Strážovské vrchy Mts. PLA | soft | 3/5 | 6/9 | 1/4 | 0/4 | 7/8 | 0/3 |

| Cerová vrchovina PLA | soft | 3/5 | 4/9 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/8 | 0/3 |

| Statements on Tourism Impact in Protected Areas | Importance | Average | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Environmental | Tourism protects and preserves the natural and cultural heritage | 4 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2.59 |

| Tourism increases the aesthetic value of the area | 4 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 2.71 | |

| Tourism educates and interprets the values of natural and cultural heritage to visitors | 0 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 3.18 | |

| Tourism informs local people about the value of natural and cultural heritage | 1 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3.29 | |

| Tourism provides greater care for the environment | 1 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 2.65 | |

| Tourism reduces the diversity of flora and fauna | 2 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 2.47 | |

| Tourism disrupts and destroys natural habitats | 2 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 3.06 | |

| Tourism causes a conflict of interest in doing business using natural resources | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3.18 | |

| Tourism decreases water and air quality | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2.41 | |

| Tourism increases noise level | 2 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2.41 | |

| Tourism causes an increase in soil erosion | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 2.71 | |

| Tourism increases waste production | 0 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 3.65 | |

| Tourism causes traffic congestion | 0 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2.82 | |

| Tourism causes the loss of natural landscape and agricultural land | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2.29 | |

| Economic | Tourism creates new job opportunities | 2 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 2.47 |

| Tourism reduces the migration of local people | 7 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2.00 | |

| Tourism is an opportunity to engage in the entrepreneurial activities of local people | 1 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 2.71 | |

| Tourism supports the development of crafts and local production of goods | 1 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 2.76 | |

| Tourism supports protected areas with funds | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2.00 | |

| Tourism uses the local workforce and its expertise | 2 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 2.88 | |

| Tourism stimulates investment in public and civic infrastructure | 3 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2.35 | |

| Tourism improves the quality of life of local people | 4 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2.24 | |

| Tourism increases the cost of living of local people | 8 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2.06 | |

| Tourism causes leakage of profits outside the region | 5 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2.00 | |

| Tourism increases the cost of road maintenance, the transport system, and additional infrastructure | 1 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 2.71 | |

| Tourism increases people’s participation in local development | 1 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 2.59 | |

| Social | Tourism contributes to the preservation of local traditions and customs | 3 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 2.53 |

| Tourism builds local patriotism | 1 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 2.88 | |

| Tourism changes the image of the region into a more attractive one | 0 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2.65 | |

| Tourism displaces local people in favor of tourism development | 8 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1.94 | |

| Tourism causes stress to locals | 7 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2.18 | |

| Tourism reduces the cohesion of local communities | 8 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.94 | |

| Tourism increases the interest of locals mainly in the economic perspective compared to the protection of the area | 0 | 6 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 2.76 | |

| Statements on Tourism Impact in Protected Areas | F | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Tourism protects and preserves the natural and cultural heritage | 0.041577 | 0.841169 |

| Tourism increases the aesthetic value of the area | 0.254825 | 0.621033 | |

| Tourism educates and interprets the values of natural and cultural heritage to visitors | 1.064909 | 0.318451 | |

| Tourism informs local people about the value of natural and cultural heritage | 1.509774 | 0.238103 | |

| Tourism provides greater care for the environment | 0.310688 | 0.585481 | |

| Tourism reduces the diversity of flora and fauna | 0.217263 | 0.647830 | |

| Tourism disrupts and destroys natural habitats | 1.077013 | 0.315808 | |

| Tourism causes a conflict of interest in doing business using natural resources | 0.619524 | 0.443483 | |

| Tourism decreases water and air quality | 1.500893 | 0.239424 | |

| Tourism increases noise level | 0.668689 | 0.426308 | |

| Tourism causes an increase in soil erosion | 3.448586 | 0.083051 | |

| Tourism increases waste production | 0.003853 | 0.951324 | |

| Tourism causes traffic congestion | 6.223529 | 0.024763 | |

| Tourism causes the loss of natural landscape and agricultural land | 2.147319 | 0.163465 | |

| Economic | Tourism creates new job opportunities | 0.011765 | 0.915064 |

| Tourism reduces the migration of local people | 0 | 1 | |

| Tourism is an opportunity to engage in the entrepreneurial activities of local people | 0.022480 | 0.882814 | |

| Tourism supports the development of crafts and local production of goods | 0.121872 | 0.731865 | |

| Tourism supports protected areas with funds | 0.162731 | 0.692346 | |

| Tourism uses the local workforce and its expertise | 1.055525 | 0.320521 | |

| Tourism stimulates investment in public and civic infrastructure | 1.941176 | 0.183845 | |

| Tourism improves the quality of life of local people | 0.929155 | 0.350366 | |

| Tourism increases the cost of living of local people | 6.257669 | 0.024432 | |

| Tourism causes leakage of profits outside the region | 5.543125 | 0.032599 | |

| Tourism increases the cost of road maintenance, the transport system, and additional infrastructure | 0.141176 | 0.712375 | |

| Tourism increases people’s participation in local development | 1.105151 | 0.30978 | |

| Social | Tourism contributes to the preservation of local traditions and customs | 1.075638 | 0.316106 |

| Tourism builds local patriotism | 2.800667 | 0.114945 | |

| Tourism changes the image of the region into a more attractive one | 0.003853 | 0.951324 | |

| Tourism displaces local people in favor of tourism development | 5.206643 | 0.037519 | |

| Tourism causes stress to locals | 2.931815 | 0.107439 | |

| Tourism reduces the cohesion of local communities | 4.053494 | 0.062384 | |

| Tourism increases the interest of locals mainly in the economic perspective compared to the protection of the area | 0.191816 | 0.667651 | |

| Text from the Examined Document | System Deficiencies, Valid Legislation of the Slovak Republic |

|---|---|

| Creating job positions in tourism | Guides: |

| Act no. 543/2002 Coll. on Nature and Landscape Protection: § 65a—guide activities in protected areas should be performed only by the SOP SR. | |

| Act 544/2002 Coll. On the Mountain Rescue Service limits the possibilities of escorting in mountain and alpine environments by introducing sections on mountain guides | |

| Act no. 170/2018 Coll. on Tours—guiding anywhere: guides in tourism must have a tied trade. | |

| Act 326/2005 Coll. on Forests—the consent of the owner in the protected areas for the permission of the guide. | |

| In cooperation with the Ministry of the Environment to address issues of sustainable tourism development | Insufficient influence of the Ministry of the Environment of the Slovak Republic on the functioning of state administration bodies for nature and landscape protection. |

| Creation of tourism products using the natural potential of the country with regard to the limits of areas requiring protection | Act no. 543/2002 Coll. on Nature and Landscape Protection does not allow movement outside the marked hiking trails from the third degree of protection, movement at night and sleeping in nature (consent of the nature protection authority—ambiguity of the system—which factor actually decides the given proceedings). |

| Geotourism and geoparks support | The majority of geosites are not listed in the national parks management plan, nor in their educational publications and promotional materials. |

| Conservation legislation rarely concerns geoconservation, due to a lack of awareness of geodiversity and recognition of the link between biotic and abiotic elements and processes. | The inventory of geosites in Slovakia does not identify their potential use for education or geotourism. |

| Elaboration of the methodology of the bearing capacities of individual regions and the creation of principles of development of sustainable tourism in protected areas. | Missing methodology for monitoring, zoning in protected areas, and setting limits, regulations as a basis for defining the visitor carrying capacity of localities—administrations of protected areas are only one of the organizational units of SOP SR, without land management, without real powers, and without its own budget, and undersized; lack of a concept for networking and cooperation between nature conservation institutions and tourism operators. |

| Text from the Tourism Development Strategy until 2020 | Shortcomings |

|---|---|

| Creation of job positions in tourism | Lack of support for job position creation, support for local craftsmen, and small and medium-sized enterprises. |

| Creation of tourism products focusing on soft tourism forms and typical local activities | Lack of interest in the use and protection of cultural heritage—a list of necessary activities for the repair and reconstruction of historic buildings, the goal of strengthening their attractiveness and making them accessible to the public. |

| Creation of tourism products using the natural potential of the territory with respect to the limits of areas requiring protection | Insufficient informing and educating visitors about the effects of their behavior on the environment and informing local people about the possibilities of conserving resources for future generations; |

| No or insufficient education for employees and the local population on sustainable tourism and cooperation between private and public sector entities and the local population. | |

| Elaboration of the methodology of the bearing capacities of individual regions and the creation of principles of development of sustainable tourism in protected areas. | No identification of problems of sustainable tourism development and activities to reduce or eliminate them. |

| Lack of focus on increasing the positive social, economic, and environmental impacts of tourism on the natural and cultural heritage and local people and eliminating negative impacts. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Štrba, Ľ.; Kolačkovská, J.; Kršák, B.; Sidor, C.; Lukáč, M. Perception of the Impacts of Tourism by the Administrations of Protected Areas and Sustainable Tourism (Un)Development in Slovakia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116696

Štrba Ľ, Kolačkovská J, Kršák B, Sidor C, Lukáč M. Perception of the Impacts of Tourism by the Administrations of Protected Areas and Sustainable Tourism (Un)Development in Slovakia. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116696

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠtrba, Ľubomír, Jana Kolačkovská, Branislav Kršák, Csaba Sidor, and Marián Lukáč. 2022. "Perception of the Impacts of Tourism by the Administrations of Protected Areas and Sustainable Tourism (Un)Development in Slovakia" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116696

APA StyleŠtrba, Ľ., Kolačkovská, J., Kršák, B., Sidor, C., & Lukáč, M. (2022). Perception of the Impacts of Tourism by the Administrations of Protected Areas and Sustainable Tourism (Un)Development in Slovakia. Sustainability, 14(11), 6696. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116696