Traditional Knowledge and Modern Motivations for Consuming Seaweed (Limu) in Samoa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Context

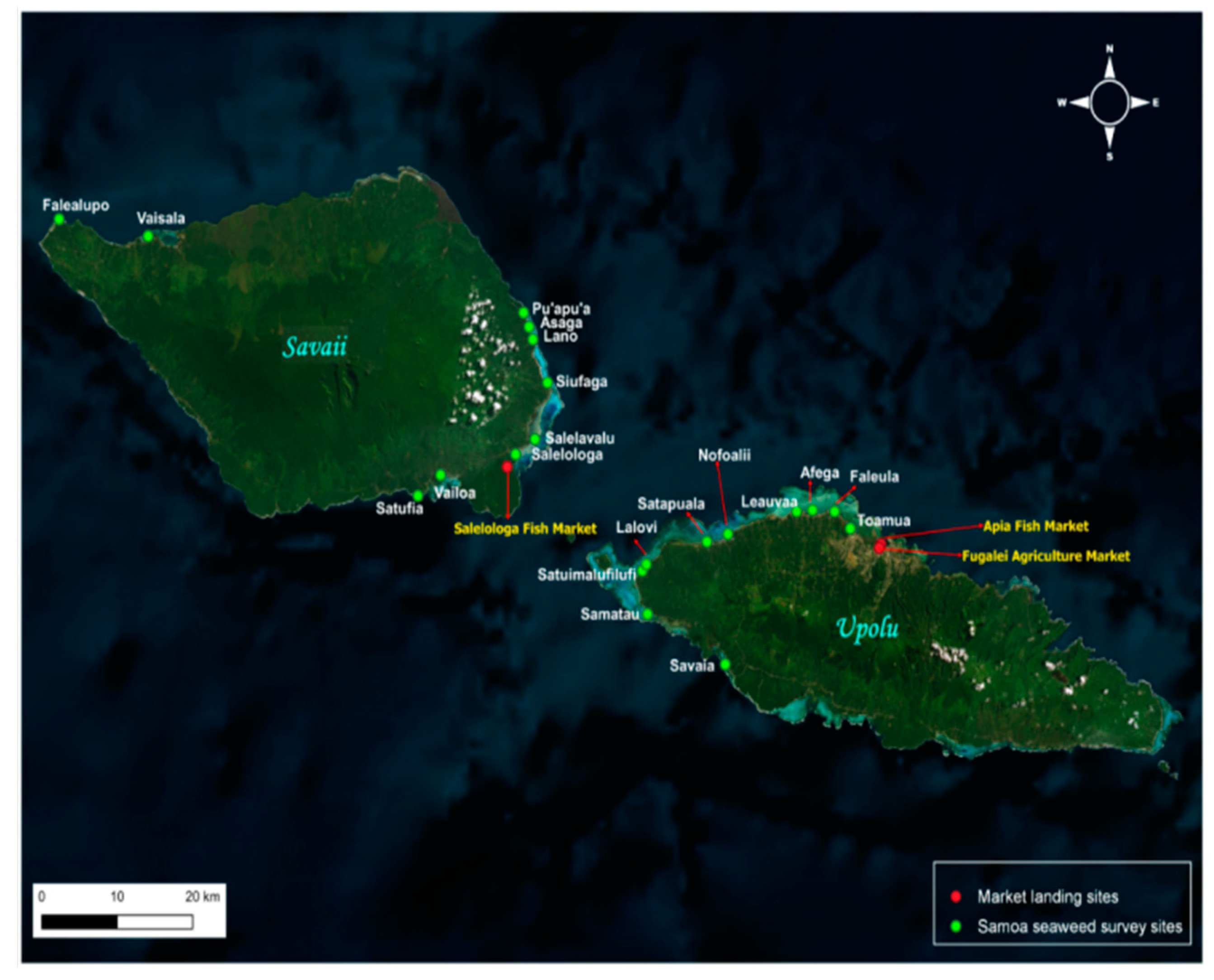

2.2. Selection of Villages

2.3. Selection of Participants

2.4. Survey Instruments

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participation Characteristics

3.2. Traditional Knowledge and Cultural Values of Seaweed

3.2.1. Knowledge of Seaweed Names

3.2.2. Cultural Values

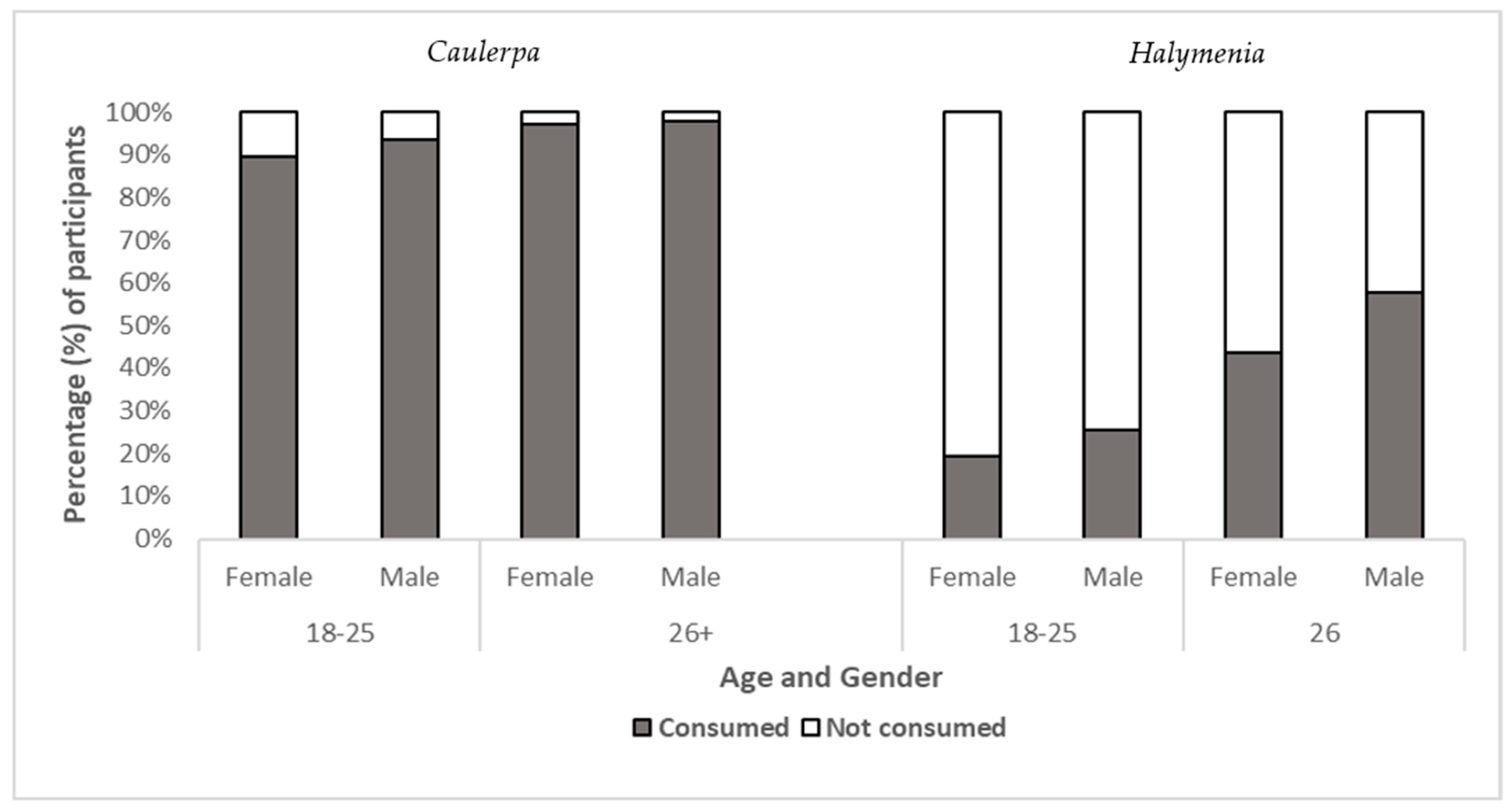

3.2.3. Utilisation and Inclusion of Seaweed in the Diet

3.3. Consumer Preferences

3.3.1. Motivators for Consuming Seaweed

3.3.2. Barriers to Consuming Seaweed

3.4. Perceived Health and Nutritional Benefits

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- South, G.R. Edible seaweeds of Fiji: An ethnobotanical study. Bot. Mar. 1993, 36, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohinejad, S.; Koubaa, M.; Barba, F.J.; Saljoughian, S.; Amid, M.; Greiner, R. Application of seaweeds to develop new food products with enhanced shelf-life, quality and health-related beneficial properties. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 1066–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L. Edible Seaweeds of the World, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, N.; Neveux, N.; Magnusson, M.; De Nys, R. Comparative production and nutritional value of “sea grapes”—The tropical green seaweeds Caulerpa lentillifera and C. racemosa. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 1833–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.; Bala, S.; South, G.; Lako, J.; Lober, M.; Simos, T. Supply chain and marketing of sea grapes, Caulerpa racemosa (Forsskål) J. Agardh (Chlorophyta: Caulerpaceae) in Fiji, Samoa and Tonga. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pickering, T. Advances in seaweed aquaculture among Pacific Island countries. J. Appl. Phycol. 2006, 18, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermid, K.J.; Martin, K.J.; Haws, M.C. Seaweed resources of the Hawaiian Islands. Bot. Mar. 2019, 62, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, G.M.; Ticktin, T.; Kelman, D.; Wright, A.D.; Tabandera, N. Contemporary Gathering Practice and Antioxidant Benefit of Wild Seaweeds in Hawai’i. Econ. Bot. 2014, 68, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanyonyi, S.; Du Preez, R.; Brown, L.; Paul, N.A.; Panchal, S.K. Kappaphycus alvarezii as a Food Supplement Prevents Diet-Induced Metabolic Syndrome in Rats. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayavel, K.; Martinez, J.A. In vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of two Hawaiian marine Limu: Ulva fasciata (Chlorophyta) and Gracilaria salicornia (Rhodophyta). J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 1494–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, I.A. The Uses of Seaweed as Food in Hawaii. Econ. Bot. 1978, 32, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, H.; Burkhart, S.; Paul, N.; Tiitii, U.; Tamuera, K.; Eria, T.; Swanepoel, L. Role of Seaweed in Diets of Samoa and Kiribati: Exploring Key Motivators for Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsey, B.; Swanepoel, L.; Underhill, S.; Aliakbari, J.; Burkhart, S. Dietary diversity of an adult Solomon Islands population. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhart, S.; Underhill, S.; Raneri, J. Realizing the Potential of Neglected and Underutilized Bananas in Improving Diets for Nutrition and Health Outcomes in the Pacific Islands. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanepoel, L.; Tioti, T.; Eria, T.; Tamuera, K.; Tiitii, U.; Larson, S.; Paul, N. Supporting Women’s Participation in Developing A Seaweed Supply Chain in Kiribati for Health and Nutrition. Foods 2020, 9, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, D.; Skallerud, K.; Paul, N. Who Eats Seaweed? An Australian Perspective. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2019, 31, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumari, P.; Trivedi, N.; Shukla, M.K.; Gupta, V.; Reddy, C.R.K.; Jha, B. Minerals, PUFAs and antioxidant properties of some tropical seaweeds from Saurashtra coast of India. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011, 23, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermid, K.J.; Stuercke, B. Nutritional composition of edible Hawaiian seaweeds. J. Appl. Phycol. 2003, 15, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulovich, R.; Umanzor, S.; Cabrera, R.; Mata, R. Tropical seaweeds for human food, their cultivation and its effect on biodiversity enrichment. Aquaculture 2015, 436, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macartain, P.; Gill, C.; Brooks, M.; Campbell, R.; Rowland, I. Nutritional Value of Edible Seaweeds. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SBS. Samoa Population and Housing Census 2016; Samoa Bureau of Statistics: Apia, Samoa, 2016.

- Birch, D.; Skallerud, K.; Paul, N. Who are the future seaweed consumers in a Western society? Insights from Australia. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.; Shannon, S. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaglehole, R.; Yach, D. Globalisation and the prevention and control of non-communicable disease: The neglected chronic diseases of adults. Lancet 2003, 362, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.; Adair, L.; Ng, S. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas García-Dorado, S.; Cornselsen, L.; Smith, R.; Walls, H. Economic globalization, nutrition and health: A review of quantitative evidence. Glob. Health 2019, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Globalization of Food Systems in Developing Countries: Impact on Food Security and Nutrition; Food and Agriculture Organisation: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, T. Lifestyle Diseases in Pacific Communities; Secretariat of the Pacific Community: Noumea, New Caledonia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, J.T. Globalisation, Urbanisation and Nutrition Transition in a Developing Island Country: A Case Study in Fiji; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schönfeld-Leber, B. Marine algae as human food in Hawaii, with notes on other Polynesian Islands. Ecol. Food Nutr. 1979, 8, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.T. Food, Society and Development; University of South Pacific: Suva, Fiji, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, P.; Thow, A.; Schuster, S.; Vizintin, P.; Negin, J. Access to a Nutritious Diet in Samoa: Local Insights. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2019, 58, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.; Dempewolf, H.; Armstrong, R.; Gallucci, K.; Tavana, N. Staple food choices in Samoa: Do changing dietary trends reflect local food preferences? Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2011, 9, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wright, A.; Hill, L. Rearshore Marine Resources of the South Pacific; International Centre for Ocean Development: Halifax, NS, Canada, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hough, G.; Sosa, M. Food Choice in Low Income Populations—A Review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.; Kalamatianou, S.; Drewnowski, A.; Kulkarni, B.; Kinra, S.; Kadiyala, S. Food Environment Research in Low- and Middle- Income Countries: A Systematic Scoping Review. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 19, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Mu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, B.; Raman, J.; Sui, Z. Double Burden of Malnutrition in the Asia-Pacific Region-A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbot, I.A.; Norris, J.N. Taxonomy of Economic Seaweeds: With Reference to Some Pacific and Caribbean Species; T-CSGCP-011; Scripps Institution of Oceanography: La Jolla, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, J.J. The problem of naming commercial seaweeds. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 32, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase-One Characteristics | Phase 1 n (%) | |

| Female | Male | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–25 | 57 (18) | 63 (20) |

| >26 | 103 (32) | 97 (30) |

| Education | ||

| Primary education | 11 (7) | 22 (14) |

| Secondary education | 129 (81) | 123 (77) |

| Vocational/technical | 3 (2) | 4 (2) |

| University | 17 (10) | 11 (7) |

| Village groups | ||

| Aualuma | 73 (23) | 0 |

| Aumaga | 0 | 93 (29) |

| Village Council | 4 (1) | 60 (19) |

| Women’s Committee | 55 (17) | 0 |

| Youth (18–25 years) | 28 (9) | 7 (2) |

| Phase-Two Characteristics | Phase 2 n (%) | |

| Female | Male | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–34 | 89 (17) | 94 (18) |

| 35–44 | 52 (10) | 49 (10) |

| 45–59 | 73 (14) | 94 (18) |

| 60+ | 30 (5) | 42 (8) |

| Motivator | Percentage of Participants | Theme Description | Example Quotes (See Note on Code Below) |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | |||

| Healthy | 47 (217) | Participants were aware that eating seafood, including seaweed, is healthy. Participants spoke about general health associations, as well as specific health benefits including the prevention and treatment of diseases. Prevention of diseases such as asthma, diarrhoea, diabetes, thyroid gland diseases, gout, high blood pressure, immune system disorders, eyesight problems, white blood cell issues and brain cell damage. |

|

| Taste and sensory | 35 (160) | Participants spoke about the freshness and pleasant salty taste as motivators for them to eat seaweeds. The sensory properties of seaweeds, such as texture, smell and appearance, were motivators for consumption. |

|

| Familiarity | 13 (62) | Participants reported that familiarity from childhood and their awareness of seaweeds motivated them to eat seaweed. |

|

| Nutrition | 4 (16) | Participants identified nutrients and were aware of the nutritional benefits of seaweeds. |

|

| Availability | 1 (5) | Participants reported that the availability of seaweed locally increased their motivation to consume seaweed. |

|

| Barrier | Percentage of Participants | Theme Description | Example Quotes (See Note on Code Below) |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | |||

| Taste | 34 (30) | Participants reported that sour and spicy tastes limited their consumption of seaweeds. |

|

| Unavailability | 24 (21) | The unavailability of seaweeds, e.g., due to the distance of their residence from the sea, and the expensive price at the market prevented consumption of seaweeds. |

|

| Unfamiliarity | 21 (19) | Unfamiliarity with the seaweeds meant that participants did not eat seaweed. |

|

| Not properly cleaned | 10 (9) | Participants reported that seaweeds are not properly cleaned during preparation. |

|

| Allergy | 6 (5) | Participants noted that consuming seaweeds triggered allergies, stomach ache and hiccups. |

|

| Sensory | 6 (5) | Sensory aspects (smell) limited consumption. |

|

| Theme Description | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Healthy and nutritious food | 245 (48) |

| Strengthens body and bones; provides energy and fights fatigue; improves blood circulation and eyesight | 225 (44) |

| Improves thyroid function; helps with diabetes, breastfeeding, brain cells, body tissues and immune system | 38 (7) |

| Contains vitamins and proteins | 6 (1) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tiitii, U.; Paul, N.; Burkhart, S.; Larson, S.; Swanepoel, L. Traditional Knowledge and Modern Motivations for Consuming Seaweed (Limu) in Samoa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6212. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106212

Tiitii U, Paul N, Burkhart S, Larson S, Swanepoel L. Traditional Knowledge and Modern Motivations for Consuming Seaweed (Limu) in Samoa. Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):6212. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106212

Chicago/Turabian StyleTiitii, Ulusapeti, Nicholas Paul, Sarah Burkhart, Silva Larson, and Libby Swanepoel. 2022. "Traditional Knowledge and Modern Motivations for Consuming Seaweed (Limu) in Samoa" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 6212. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106212

APA StyleTiitii, U., Paul, N., Burkhart, S., Larson, S., & Swanepoel, L. (2022). Traditional Knowledge and Modern Motivations for Consuming Seaweed (Limu) in Samoa. Sustainability, 14(10), 6212. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106212