Taneyan Lanjang Shared Home Gardens and Sustainable Rural Livelihoods of Ethnic Madurese in Madura Island, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

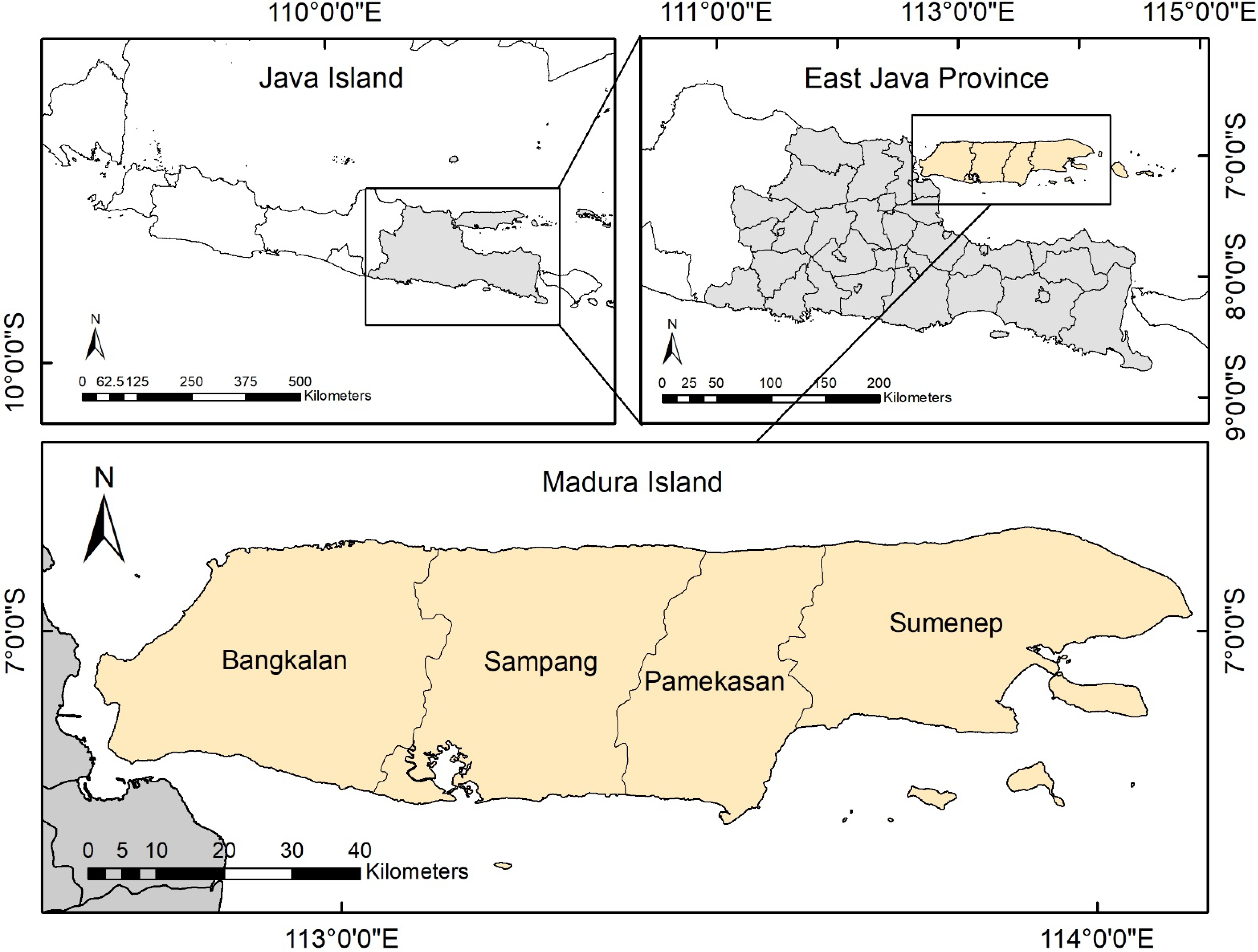

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Description of Participants, TLs, and SHGs

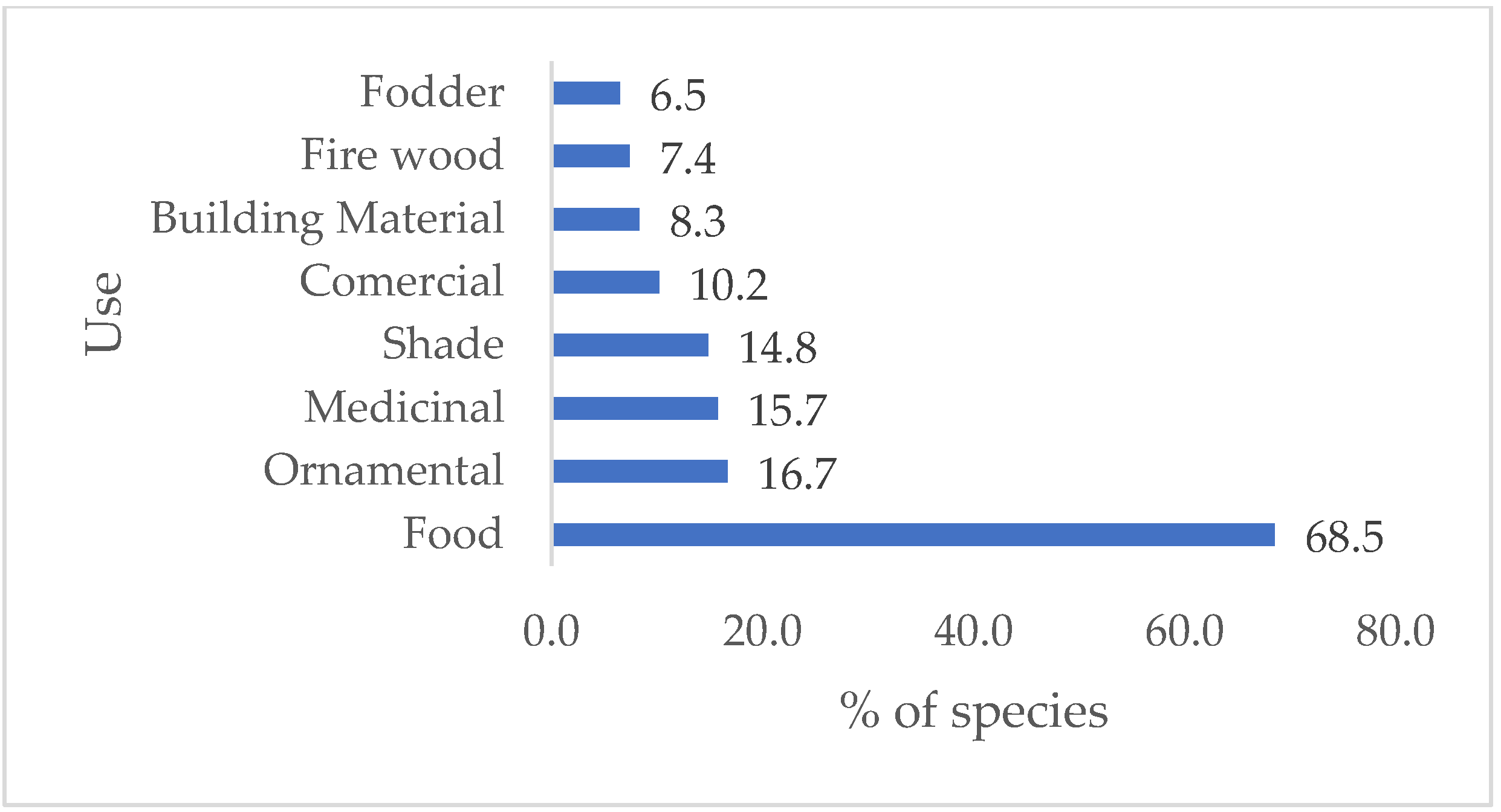

3.2. SHG Plant Species’ Major Use Categories

“The banana tree is a plant that is simple to cultivate, produces fruit all year that tastes delicious. Usually, we consume bananas from our family garden.”(Male, 50).

“The mango tree is a plant that grows well in dry, low-fertility areas like Madura. You will find mango trees in some home gardens in Madura Island.”(Male, 45).

“Because of the hot weather in Madura, we use mango trees not only to harvest their fruit but also to provide shade to make our home cooler.”(Male, 55).

“We are used to consuming a mixture of rice and corn as a staple food, so we decided to plant corn in our garden.”(Female, 50).

“Apart from rice, we eat maize, cassava, and sweet potatoes as staple foods. Cassava is dried, stored and used as reserve food, especially when our rice or corn reserves are running low.”(Female, 36).

“In our garden, we grow peanuts, but we only eat a small fraction of them. We usually sell them in the neighborhood market, and the stems and leaves are used as fodder.”(Female, 54).

“Moringa is a very common vegetable in our daily food consumption. This plant is easy to grow and we believe it is good for our health.”(Female, 54).

“Sometimes we use shoeblack plants to feed our goats. I remember one time when I was sick and could not find any forage. My wife trimmed those plants and fed them to our goats.”(Male, 38).

“We cultivate Javanese long pepper for a traditional medicine called ‘jamu’. It is a commercial commodity, quite expensive, and we usually sell it to middlemen.”(Male, 42).

“We cultivate curcuma, galanga, and ginger near the outdoor bathroom, utilizing the wastewater for irrigation. We use those plants as a source of traditional medicine for our family.”(Male, 42).

“The most used construction material in our settlement is bamboo from our garden.”(Male, 55).

“Bamboo shoots are cooked as a vegetable with spices (onion, garlic, and chili) and coconut milk. It is tasty.”(Female, 37).

3.3. Local Knowledge and Management Practice of SHG

“Industrial fertilizers are expensive and sometimes difficult to obtain. We use them for the main crops in the fields. On the other hand, we prefer to use compost for the plants in our garden.”(Male, 42).

“Fencing is necessary not only as a barrier and protection, but also as a source of healthy food. For example, the sweet leaf plant is a nutritious food for breastfeeding mothers.”(Female, 30).

“Our religion states that men are leaders (in charge of women) and must be responsible for their families and respect women. We handle heavy work, but we still cooperate with each other in various activities.”(Male, 65).

“The men tend to the primary crops in the fields, while the women tend to our garden. However, men will still perform some of the heavy activities, i.e., land preparation and the pruning of high-growing plants.”(Female, 50).

“In daily life, we attempt to be submissive to our spouses, even in the management and utilization of the garden.”(Female, 43).

3.4. SHG Functions and Services to Rural Livelihoods

- Provision of daily food nutritionThe primary function of the SHG is to produce food as a supplement to the daily nutrition in rural areas. The total production from the farm fields and the SHG can supply food for a whole year and provide rural households with cereals, tubers, vegetables, fruits, and spices. We noted that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the respondents felt no worry about their daily food because they had enough food in storage (both from their farm fields and the SHG). In accordance with previous studies [104,105,106,107], the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on household income. Households reduced expenditure on food by utilizing their SHGs. This is in line with previous studies [108], which found that home gardens played an important role in advancing food and nutritional security during and after the COVD-19 pandemic. Madurese farmers grow rice and corn as the most important staple crops. Rice is harvested from paddy fields and kept as grain—it is never sold. When the rice supply gets low, they grind it. Dried corn with husks is hung in the kitchen or the storeroom. Food provisioning was the most frequently mentioned ecosystem service, especially in rural areas [109]. Most families depend on their home garden for food. Thus, they grow plants that can meet their basic needs, thereby reducing their daily food expenses.

“Despite the fact that we are in a COVID-19 pandemic, we are not concerned about food shortages. We have rice and corn (from the fields), as well as other food crops in our SHG.”(Male, 43).

“Our family prefers to eat eggs and poultry that we raise ourselves because they taste better and we also save money. We are pleased to be able to provide for the family’s nutritional needs using garden produce, both plants and livestock.”(Female, 43).

“We bought less veggies (carrots, potatoes, and cabbage) and replaced them with moringa, cassava leaf, and young jackfruit, which we can harvest from our SHG to save money during the pandemic.”(Female, 32).

“We do not have to worry about becoming hungry because of COVID-19 at any moment. We can take cassava, taro, sweet potato, or corn from our garden if we are hungry, and then boil or fry them.”(Male, 67).

- 2.

- Additional income and saving systemThe home garden represents an integrated production system for family income [110]. We found that ethnic Madurese women sell cereals, tubers, fruits, vegetables, and chili peppers grown in their SHG at the nearest traditional market to get additional income. The income from food sales was only a supplemental source of income for all rural households, not a major one. An SHG can contribute 10% to 15% of the monthly household income, which agrees with the findings of a previous study conducted in Jenggolo Village, Malang, East Java [30]. However, in the latter instance, the contribution to the household income from such sales was greater.

“We were short on cash at the time and our extended family needed immediate assistance, so we decided to sell the bamboo in the garden.”(Male, 62).

“My child entered college last year and it was rather expensive. Fortunately, we had cows to sell. Yes, raising a cow is a great way to save money that may be put to good use at any moment.”(Male, 62).

- 3.

- Agrobiodiversity reservoirSHGs can be considered agrobiodiversity reservoirs on a micro-regional scale and are important areas for in-situ and on-farm conservation [111]. Home gardens play an important role in biodiversity conservation, especially for local traditional crop varieties. Local crop varieties are grown in SHGs by Madurese farmers to conserve seeds and for other reasons as well (preferences). For example, we recorded local varieties of Zea mays L., Allium cepa L., and Cucumis sativus L. in the SHGs. Most farmers (75%) do not accept hybrid varieties. They believe that local varieties are tastier: the maize is sweeter, the onion has a stronger scent, and the cucumbers are crunchier. Rural communities have a tradition of exchanging seeds, which also contributes to the richness of genetic diversity (local variety conservation).

“We prefer to plant a local variety (of Madurese corn), both in the fields and in the garden. It tastes better, even though it is smaller than hybrid varieties, and we want to preserve it.”(Male, 62)

“The strong scent of Sumenep shallots and the crispness of yellow cucumbers are my favorites. We are attempting to conserve both of these local types, which are becoming increasingly rare. I am out of seeds at the moment, so I have asked my brother to plant some in the garden.”(Female, 50).

- 4.

- Fuel storageSHGs produce firewood that is commonly used for cooking in TLs. Rural households use subsidized liquid gas for cooking, but they prefer to use firewood in their daily lives; liquid gas is only used for simple cooking activities, such as boiling water for making coffee or tea. The ethnic Madurese strictly use firewood for cooking during religious activities and festival celebrations. Several cultural and religious activities are held in TLs [37]; the more activities, the more firewood is needed.

“I often cook using firewood, which reduces expenses for buying LPG (liquid petroleum gas).”(Female, 50).

“Several species of trees in the garden provide both fuel and animal fodder. We frequently cook using leftover animal feed.”(Male, 40).

- 5.

- Livestock shelterLivestock is an essential part of ethnic Madurese culture, especially cattle. The SHG plays an important role in providing fodder for family-raised livestock in the TLs. Pennisetum purpureum Schumach. (elephant grass) is the plant most commonly used as fodder for cattle. Corn stalks, both dry and fresh, are also used as fodder. On the other hand, livestock manure that is kept also produces organic fertilizer.Cattle are the most important livestock raised by households in TLs. Every household has a minimum of two cattle. This finding is in line with the previous research by Nugroho [112]. The motives for keeping cattle are saving, manure production, income, social status, and cultural values [113]. Usually, parents give cattle to their daughters when they get married as capital for setting up their new life. Small ruminants, such as goats and sheep, are also kept by the ethnic Madurese. They will sell cattle, goats, or sheep if they have a large expenditure, for example, school fees, a wedding ceremony, tobacco planting capital, the Feast of Sacrifice, etc. Chickens, ducks, and swans are also kept in the TLs and mainly consumed for self-sufficiency. A small number of eggs are sold in a traditional market for additional income. Additionally, some birds are raised as a hobby (pigeons, love birds).

“For the Madura tribe, cows are a specific type of cattle. My in-laws’ family gave me a cow when I got married.”(Female, 50).

- 6.

- Social and cultural servicesTLs and SHGs are used for daily activities, spatial arrangement, health, enjoyment, personal satisfaction, and social satisfaction [30]. Drying agriculture products, washing and drying clothes, raising livestock, playing, doing carpentry, and other activities are conducted daily in the TLs. Products from the TL and SHG play an important role in traditional festival celebrations and religious activities. Madurese people’s marriages, funerals, festivals, and religious ceremonies must be carried out in their TL. SHG products are used for various ceremonies, especially fruit, chickens, and eggs. We note that families conserve and maintain their TL because they need a large space for reunions with their extended family and use products from their SHG during those events. SHG products are also shared with others, such as neighbors and guests who visit the TL. As a result, the SHG also contributes to the community′s social network [114]. All of our respondents stated that they feel happiness when they share with others.

“In Islam, we are encouraged to give charity. The fruit I harvest from my garden is shared with my neighbors and relatives outside the village. This is a banana harvest from the garden. Please eat it and take it home. It feels very good when we can share and believe that God will give us more.”(Male, 63).

- 7.

- Regulating servicesStudies on ecosystem services and environmental benefits of SHGs highlight various regulating services they offer [30,114,115]. Some plant species that are found in most SHGs are used for providing shade: Cananga odorata (Lam.) Hook. f. & Thomson, Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam (jackfruit), Dalbergia latifolia Roxb. (rosewood), Dimocarpus longan Lour. (longan), Hibiscus tiliaceus var. abutiloides (Willd.) Hochr., Lannea coromandelica (Houtt.) Merr., Mangifera indica L., Muntingia calabura L. (cotton candy berry), Nephelium lappaceum L. (hairy lychee), Persea americana Mill. (avocado), Pterocarpus indicus Willd. (Burmese rosewood), Samanea saman (Jacq.) Merr. (rain tree), Swietenia macrophylla King. (big leaved mahogany), Syzygium aqueum (Burm. f.) Alston (water apple), Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels (black plum), and Tamarindus indica L. (tamarind). These plants are easy to grow and resistant to strong gusts of wind, as their branches and twigs do not break easily. Multipurpose species often form the core of the SHG and create microclimates and soil conditions favorable for the cultivation of many other species [115].

“Plants that have grown up have lush leaves that are very comfortable to shelter under and feel the fresh wind. It is better when you can enjoy the fruit and eat it with your family under a tree.”(Male, 63).

4. Conclusions

- It is necessary to improve education, especially for the youth, to explain how important SHGs are. The younger generations can promote and develop tourism in TLs and SHGs to provide economic benefits;

- Given the traditional nature of SHG management, the low productivity of SHGs, and the opportunity tourism development provides, the local government and the university in Madura Island can help to protect the TLs and SHGs and improve the productivity of plant species, specifically those with high economic value, by providing trainings, extension activities, and establishing an SHG related institution.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Plant Taxon (Species) | Family | English Name | Vernicular Name | Utilization * | RF ** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | Madurese | Ctg | PU | (%) | |||

| Adenium obesum (Forssk.) Roem. & Schult. | Apocynaceae | Desert rose | Kamboja | Kamboja | Or | Fl | 2 |

| Allium cepa L. | Liliaceae | Onion | Bawang merah | Bhabang merah | Fd, Cm | Tu | 5 |

| Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. | Asphodelaceae | Aloe vera | Lidah buaya | Jhilê bhâjê | Md, Or | Le | 5 |

| Alpinia galanga (L.) Willd. | Zingiberaceae | Siamese ginger | Lengkuas | Laos | Fd | Rz | 20 |

| Amaranthus sp. | Amaranthaceae | Amarant/spinach | Bayam | Tarnya’ | Fd | Le | 10 |

| Amorphophallus oncophyllus Prain ex Hook.f. | Araceae | Konjac | Porang | Subeg Leres | Fd | Tu | 38 |

| Anacardium occidentale L. | Anacardiaceae | Cashew | Jambu Mente | Jâmbhu Monyet | Fd, Cm | Fr, Se | 33 |

| Annona muricata L. | Annonaceae | Soursop | Sirsak | Sarkajhê | Fd | Fr | 10 |

| Annona squamosa L. | Annonaceae | Sugar apple | Srikaya | Sorkajeh | Fd | Fr | 8 |

| Arachis hypogaea L. | Fabaceae | Peanut/groundnut | Kacang tanah | Kacang tana | Fd, Cm, Fo | Se | 62 |

| Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson ex F.A.Zorn) Fosberg | Moraceae | Breadfruit | Sukun | Sokon | Fd | Fr | 10 |

| Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. | Moraceae | Jackfruit | Nangka | Nangkah | Fd, Sh | Fr | 35 |

| Averrhoa bilimbi L. | Oxalidaceae | Bilimbi | Belimbing wuluh | Blimbhing Buluh | Fd, Md | Fr | 4 |

| Averrhoa carambola L. | Oxalidaceae | Star fruit | Belimbing | Bhlimbhing | Fd | Fr | 8 |

| Bambusa glaucescens (Willd.) Merr. | Poaceae | Bamboo | Bambu | Pêrreng | Fd, BM, FW, Cm | Tb, St | 75 |

| Basella rubra L. | Basellaceae | Malabar spinach | Binahong | Kandula | Md | Le | 5 |

| Borassus flabellifer L. | Palmae | Palmira | Lontar, Siwalan | Ta’al | Fd | Fr | 4 |

| Bougainvillea spp. | Nyctaginaceae | Paper flower | Bugenvil | Bunga kertas | Or | Fl | 6 |

| Caladium bicolor (Aiton) Vent. | Araceae | Caladium | Keladi | Kembhâng tales | Or | Le | 8 |

| Cananga odorata (Lam.) Hook.f. & Thomson | Annonaceae | Perfume tree | Kenanga | Kenanga | Or, Sh | Fl | 4 |

| Canarium ovatum Engl. | Burseraceae | Walnut | Kenari | Kenari | Fd | Fr | 3 |

| Capsicum annum L. | Solanaceae | Cayenne pepper | Cabai besar | Cabbhi rajhê | Fd | Fr | 13 |

| Capsicum frutescens L. | Solanaceae | Chili pepper | Cabai Rawit | Cabbhi keni’ | Fd, Cm | Fr | 69 |

| Carica papaya L. | Caricaceae | Papaya | Pepaya | Kates | Fd | Fr, Le, Fl | 49 |

| Catharanthus roseus (L.) G.Don | Apocynaceae | Periwinkle | Tapak dara | Tapak dara | Or | Fl | 3 |

| Ceiba pentandra (L.) Gaertn. | Bombacaceae | Kapok-tree | Kapuk Randu | Kapo | Cm, FW | Fr, Tb | 2 |

| Chrysophyllum cainito L. | Sapotaceae | Star apple/caimito | Kenitu | Menitu | Fd | Fr | 2 |

| Citrus amblycarpa (Hassk.) Ochse | Rutaceae | Java lime | Jeruk limau | Jhêrruk bujhel | Fd | Fr | 13 |

| Citrus aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle | Rutaceae | Key lime | Jeruk Nipis | Jhêrruk peccel | Fd | Fr | 13 |

| Citrus hystrix DC. | Rutaceae | Kaffir lime | Jeruk purut | Jhêrruk porot | Fd | Fr, Le | 11 |

| Citrus paradisi Macfad. | Rutaceae | Grapefruit/pomelo | Jeruk Bali | Jhêrruk Bali | Fd | Fr | 7 |

| Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck | Rutaceae | Sweet orange | Jeruk Manis | Jhêrruk Manes | Fd | Fr | 12 |

| Cocos nucifera L. | Arecaceae | coconut | Kelapa | Nyior | Fd, BM, FW | Fr, Tb | 41 |

| Codiaeum variegatum (L.) Rumph. ex A.Juss. | Euphorbiaceae | Croton | Puring | Karoton | Or | Le | 8 |

| Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott | Araceae | Taro | Talas | Talês | Fd | Tu, St | 47 |

| Cosmos caudatus Kunth | Asteraceae | Wild cosmos | Kenikir | Knikir | Fd | Le | 28 |

| Cucumis sativus L. | Cucurbitaceae | Cucumber | Mentimun | Temon | Fd, Cm | Fr | 4 |

| Cucurbita maxima Duchesne | Cucurbitaceae | Pumpkin | Labu kuning | Labuh | Fd | Fr | 4 |

| Curcuma longa L. | Zingiberaceae | Turmeric | Kunyit | Konyek | Fd, Md | Rz | 63 |

| Curcuma rotunda L. | Zingiberaceae | Fingerroot | Kunci | Konceh | Fd, Md | Rz | 46 |

| Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb | Zingiberaceae | Javanese turmeric | Temulawak | Temo labek | Md | Rz | 51 |

| Curcuma zedoaria (Christm.) Roscoe | Zingiberaceae | Zedoary | Kunyit Putih | Konyek pote | Md | Rz | 45 |

| Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf | Poaceae | Lemongrass | Serai | Sereh | Fd, Md | Le | 45 |

| Dalbergia latifolia Roxb. | Fabaceae | Rosewood | Kayu Sono | Kaju Sono | BM, Sh, FW | Tb | 5 |

| Dimocarpus longan Lour. | Sapindaceae | Longan | Kelengkeng | Klèngkèng/Khmer | Fd, Sh | Fr | 13 |

| Dracaena angustifolia (Medik.) Roxb. | Asparagaceae | Soap tree | Pandan suji | Pandhen Sojih | Fd | Le | 13 |

| Durio zibethinus L. | Malvaceae | Durian | Durian | Dhurian | Fd | Fr | 13 |

| Dypsis lutescens (H.Wendl.) Beentje & J.Dransf. | Arecaceae | Butterfly palm | Palem | Palem | Or | Le | 7 |

| Euphorbia milii Des Moul. | Euphorbiaceae | Crown of thorns | Bunga Euporbia | Seribu duri | Or | Fl | 8 |

| Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L. | Malvaceae | Chinese hibiscus, shoeblack plant | Bunga Sepatu | Kembhâng sepatu | Or, Fo | Fl | 47 |

| Hibiscus sabdariffa L. | Malvaceae | Roselle | Rosella | Rosella | Fd, Or | Fl | 3 |

| Hibiscus tiliaceus var. abutiloides (Willd.) Hochr. | Malvaceae | Sea hibiscus | Waru | Beruh | BM, Sh, FW | Tb | 8 |

| Hylocereus undatus (Haw.) Britton & Rose | Cactaceae | Dragon fruit | Buah Naga | Buah Naga | Fd | Fr | 5 |

| Impatiens balsamina L. | Balsaminaceae | Rose balsam | Bunga pacar air | Pacar kuku | Or | Fl | 7 |

| Ipomoea aquatica | Convolvulaceae | Water spinach | Kangkung | Kangkung | Fd | Le | 13 |

| Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam. | Convolvulaceae | Sweet potato | Ubi jalar | Sabbrêng longghê | Fd | Tu | 61 |

| Ixora coccinea L. | Rubiaceae | Jungle geranium | Asoka | Kembhâng Soka | Or | Fl | 3 |

| Jasminum sambac (L.) Aiton | Oleaceae | Jasmine | Melati | Malate | Or | Fl | 16 |

| Jatropha multifida L. | Euphorbiaceae | Coral plant | Bunga betadine | Penisilin | Md | Le | 1 |

| Kaempferia galanga L. | Zingiberaceae | Aromatic ginger | Kencur | Kencor | Md | Rz | 43 |

| Lagenaria leucantha (Duchesne) Rusby | Cucurbitaceae | Calabash | Labu air | Labuh Lente | Fd | Fr | 2 |

| Lannea coromandelica (Houtt.) Merr. | Anacardiaceae | Indian ash tree | Kayu jaran | Ki jaran | BM, Sh, FW | Tb | 6 |

| Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit | Fabaceae | White leadtree | Lamtoro | Lantoro | Fd, Fo | Se, Le | 3 |

| Luffa acutangula (L.) Roxb. | Cucurbitaceae | Oyong/gambas | Oyong | Langkèr | Fd | Fr | 2 |

| Manilkara zapota (L.) P.Royen | Sapotaceae | Sapodilla | Sawo | Sabu manila | Fd | Fr | 88 |

| Mangifera indica L. | Anacardiaceae | Mango | Mangga | Pao | Fd, Cm, Sh | Fr | 76 |

| Manihot esculenta Crantz | Euphorbiaceae | Cassava | Singkong | Sabbrêng kaju | Fd | Tu | 13 |

| Morinda citrifolia | Rubiaceae | Indian mulberry | Mengkudu | Koddhu’ | Md | Fr | 3 |

| Moringa oleifera Lam. | Moringaceae | Moringa | Kelor | Marongghi | Fd | Le | 73 |

| Morus alba L. | Moraceae | White mulberry | Murbei | Murbei | Fd | Fr | 4 |

| Muntingia calabura L. | Muntingiaceae | Cotton candy berry | Kersen | Kersen baleci | Fd, Sh | Fr | 33 |

| Musa spp. | Musaceae | Banana | Pisang | Geddeng | Fd | Fr | 98 |

| Nephelium lappaceum L. | Sapindaceae | Hairy lychee | Rambutan | Rambutan | Fd, Sh | Fr | 4 |

| Ocimum basilicum L. | Lamiaceae | Sweet basil | Kemangi | kemangék | Fd | Le | 3 |

| Opuntia spp | Cactaceae | Prickly pear | Kaktus | kaktus | Or | St | 1 |

| Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb. | Pandanaceae | Screwpine | Pandan wangi | Pandhen Ro’om | Fd | Le | 13 |

| Passiflora edulis Sims | Passifloraceae | Passionfruit | Markisa | Markisa | Fd | Fr | 2 |

| Pennisetum purpureum Schumach. | Poaceae | Elephant grass | rumput gajah | Rêbbhê ghêjhê | Fo | Le, St | 8 |

| Persea americana Mill. | Lauraceae | Avocado | Alpukat | Apokat | Fd, Sh | Fr | 12 |

| Phaseolus aureus Roxb. | Fabaceae | Mung bean | Kacang Hijau | Arta’ | Fd, Fo | Se | 23 |

| Phoenix dactylifera L. | Arecaceae | Date palm | Kurma | Korma | Fd | Fr | 1 |

| Piper betle L. | Piperaceae | Betel pepper | Sirih | Sêrre | Md | Le | 28 |

| Piper retrofractum Vahl | Piperaceae | Javanese long pepper | Cabe jamu | Cabbhi jhêmo | Md, Cm | Fr | 65 |

| Pluchea indica (L.) Less. | Compositae | Indian pulchea | Beluntas | Beluntas | Fd, Md | Le | 13 |

| Psidium guajava L. | Myrtaceae | Guava | Jambu Biji | Jhêmbhu bighi | Fd | Fr | 19 |

| Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (L.) DC | Fabaceae | Winged bean | Kecipir | Kecêpêr | Fd | Fr | 1 |

| Pterocarpus indicus Willd. | Fabaceae | Burmese rosewood | Angsanah | Sana Kembhâng | BM, Sh | Tb | 5 |

| Punica granatum L. | Lythraceae | Pomegranate | Delima | Dhalima | Fd | Fr | 8 |

| Rosa spp. | Rosaceae | Rose | Mawar | Kembhâng Mawar | Or | Fl | 13 |

| Salacca zalacca (Gaertn.) Voss | Arecaceae | Snake fruit | Salak | Salak | Fd | Fr | 15 |

| Samanea saman (Jacq.) Merr. | Fabaceae | Rain tree | Kayu hujan | Kaju ojhân | BM, Sh, FW | Tb | 8 |

| Sandoricum koetjape (Burm.f.) Merr. | Meliaceae | Cotton fruit | Kecapi | Sentol | Fd | Fr | 1 |

| Sansevieria trifasciata Prain | Asparagaceae | Snake plant | Lidah mertua | Mandafika | Or, Md | St | 15 |

| Sauropus androgynous Merr | Phyllanthaceae | sweet leaf | Katuk | Kelakor | Fd | Le | 15 |

| Sechium edule (Jacq.) Sw. | Cucurbitaceae | Chayote | Labu siam | Manisah | Fd | Fr | 6 |

| Sesbania grandiflora (L.) Pers. | Fabaceae | Vegetable hummingbird | Turi | Toroi | Fd, Fo | Fl, Le | 35 |

| Solanum lycopersicum L. | Solanaceae | Tomato | Tomat | Tomat | Fd, Cm | Fr | 10 |

| Solanum melongena L. | Solanaceae | Eggplant | Terong | Têrrong | Fd | Fr | 33 |

| Sonchus arvensis L. | Asteraceae | Perennial sowthistle | Tempuyung | Tempuyung | Or | Rz | 27 |

| Spondias cytherea Sonn | Anacardiaceae | Golden apple | Kedongdong | Kedundung | Fd | Fr | 13 |

| Swietenia macrophylla King | Meliaceae | Big leaved mahogany | Mahoni | Mahoni | BM, Sh, FW | Tb | 6 |

| Syzygium aqueum (Burm.f.) Alston | Myrtaceae | Water apple | Jambu Air | Jhembuh Klampo’ | Fd, Sh | Fr | 48 |

| Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels | Myrtaceae | Black plum | Jamblang | Duwet | Fd, Sh, FW | Fr | 10 |

| Tamarindus indica L. | Fabaceae | Tamarind | Asem | Accem/komancer | Fd | Fr, Sh | 7 |

| Tectona grandis L.f. | Lamiaceae | Teak | Jati | Jhâte | BM, Cm | Tb | 32 |

| Vigna sinensis L. | Fabaceae | Long bean | Kacang panjang | Otok | Fd, Fo | Fr, Le | 13 |

| Zea mays L. | Poaceae | Corn | Jagung | Jâghung | Fd, Fo | Fr | 78 |

| Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Zingiberaceae | Ginger | Jahe | Jhâi | Fd, Md | Rz | 46 |

References

- Ferdous, Z.; Datta, A.; Anal, A.K.; Anwar, M.; Khan, A.S.M.M.R. Development of home garden model for year round production and consumption for improving resource-poor household food security in Bangladesh. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2016, 78, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galhena, D.H.; Freed, R.; Maredia, K.M. Home gardens: A promising approach to enhance household food security and wellbeing. Agric. Food Secur. 2013, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresco, L. Homegarden Systems: Agricultural Characteristics and Challenges; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Calvet-Mir, L.; Riu-Bosoms, C.; González-Puente, M.; Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Reyes-García, V.; Molina, J.L. The Transmission of Home Garden Knowledge: Safeguarding Biocultural Diversity and Enhancing Social–Ecological Resilience. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2016, 29, 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Hernández, M.; Denmead, L.H.; Clough, Y.; Raffiudin, R.; Tscharntke, T. Cultural homegarden management practices mediate arthropod communities in Indonesia. J. Insect Conserv. 2016, 20, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, T.; Bosseva, Y.; Chervenkov, M.; Dimitrova, D. Enough to feed ourselves!—Food plants in bulgarian rural home gardens. Plants 2021, 10, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muliawati, E.S.; Budiastuti, M.T.S.; Suprayogo, D.; Sutrisno, J. Agrobiodiversity in the rural home gardens as the food reserve for climate change adaptation (Case study: Samin sub-watershed, Central Java, Indonesia). Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 24, 759–767. [Google Scholar]

- Gifawesen, S.T.; Tola, F.K.; Duguma, M.S. Review on Role of Home Garden Agroforestry Practices to Improve Livelihood of Small Scale Farmers and Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation. J. Plant Sci. 2020, 8, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersum, K.F. Diversity and change in homegarden cultivation in Indonesia. In Tropical Homegardens: A Time-Tested Example of Sustainable Agroforestry; Kumar, B.M., Nair, P.K.R., Eds.; Springer Science: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naigaga, H.; Ssekandi, J.; Ngom, A.; Sseremba, G.; Mbaye, M.S.; Noba, K. Ethnobotanical knowledge of home garden plant species and its effect on home garden plant diversity in Thies region of Senegal. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 23, 7524–7536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palestina-González, M.I.; Carranza-Cerda, I.; López-Reyes, L.; Torres, E.; Silva-Gómez, S.E. Sustainability assessment of traditional agroecosystems in the high region of yaonáhuac, puebla, mexico. Environments 2021, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milow, P.; Ramli, M.R.; Chooi, O.H. Preliminary survey on plants in home gardens in Pahang, Malaysia. J. Biodivers. 2010, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, L.N.; Watson, J.W.; Hue, N.N.; De, N.N.; Minh, N.V.; Chu, P.; Sthapit, B.R.; Eyzaguirre, P.B. Agrobiodiversity conservation and development in Vietnamese home gardens. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003, 97, 317–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammohan, A.; Pritchard, B.; Dibley, M. Home gardens as a predictor of enhanced dietary diversity and food security in rural Myanmar. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patalagsa, M.A.; Schreinemachers, P.; Begum, S.; Begum, S. Sowing seeds of empowerment: Effect of women’s home garden training in Bangladesh. Agric. Food Secur. 2015, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S. Gender role in home garden management in the indigenous community: A case study in Bandarban hill district, Bangladesh. Int. J. Soc. For. 2012, 5, 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M.; Geiger, K.; Singhakumara, B.M.P.; Ashton, M.S. Quantitatively characterizing the floristics and structure of a traditional homegarden in a village landscape, Sri Lanka. Agrofor. Syst. 2019, 93, 1439–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, D.; García, N. Food plants in home gardens of the Middle Magdalena basin of Colombia. Caldasia 2017, 39, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyé-Mengual, E.; Gasperi, D.; Michelon, N.; Orsini, F.; Ponchia, G.; Gianquinto, G. Eco-efficiency assessment and food security potential of home gardening: A case study in Padua, Italy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agize, M.; Demissew, S.; Asfaw, Z. Indigenous knowledge on management of home gardens and plants in loma and Gena Bosa Districts (Weredas) of Dawro Zone, Southern Ethiopia: Plant biodiversity conservation, sustainable utilization and environmental protection. Int. J. Sci. Basic Appl. Res. 2013, 10, 63–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mathewos, M.; Hundera, K.; Biber-Freudenberger, L. Planting fruits and vegetables in homegarden as a way to improve livelihoods and conserve plant biodiversity. Agriculture 2018, 8, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Serrano, V.; McLaren, B.; Carrasco, J.C.; Alday, J.G.; Fiallos, L.; Amigo, J.; Onaindia, M. Traditional ecological knowledge and medicinal plant diversity in Ecuadorian Amazon home gardens. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 17, e00524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangjang, S.; Arunachalam, A. Role of traditional home garden systems in Northeast India. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2009, 8, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Salako, V.K.; Fandohan, B.; Kassa, B.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Idohou, A.F.R.; Gbedomon, R.C.; Chakeredza, S.; Dulloo, M.E.; Kakaï, R.G. Home gardens: An assessment of their biodiversity and potential contribution to conservation of threatened species and crop wild relatives in Benin. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2014, 61, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birol, E.; Bela, G.; Smale, M. The role of home gardens in promoting multi-functional agriculture in Hungary. EuroChoices 2005, 4, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumari, J.; Prabha, V.S.; Rayan, E.J.; Raj, T.L.S.; Antony, S.B. Floristic Diversity Assessment of Home Garden in Palayamkottai Region of Tirunelveli District, Tamil Nadu a Means of Sustainable Biodiversity Conservation. Int. J. Trend Sci. Res. Dev. 2019, 3, 1484–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvet-Mir, L.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Reyes-García, V. Beyond food production: Ecosystem services provided by home gardens. A case study in Vall Fosca, Catalan Pyrenees, Northeastern Spain. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 74, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Woo, S.Y.; Kwak, M.J.; Lee, J.K.; Leti, S.; Soni, T. Assessment of the diverse roles of home gardens and their sustainable management for livelihood improvement in West Java, Indonesia. Forests 2019, 10, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soemarwoto, O.; Conway, G.R. The Javanese homegarden. J. Farming Syst. Res. 1991, 2, 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Nurlaelih, E.E.; Hakim, L.; Rachmansyah, A.; Antariksa, A. Landscape services of home garden for rural household: A case study of Jenggolo village Malang regency. Agric. Soc. Econ. J. 2019, 19, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dzulkarnain, I. Diversity relationship based on local wisdom in Madura. In Proceedings of the UMM International Conference on Pure and Applied Research (UMM-ICOPAR), Malang, Indonesia, 21–22 August 2015; pp. 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- Maningtyas, R.T. Study of Traditional Settlement Landscape Design. Master’s Thesis, Bogor Agriculture University, Bogor, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maningtyas, R.T.; Gunawan, A. Taneyan lanjhang, study of home garden design based local culture of Madura. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 91, 12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rumi, U.; Atiqullah, A. Kobhung, gender, and religion: Husband and wife power relations in Madurese culture. Harmoni 2019, 18, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzulkarnain, I. The high cost of a Madurese civilization: The false love of Madura culture (Madura reflection after two years of Suramadu bridge). Kariman 2013, 1, 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Umam, S.; Pratama, A.A. The values of Islamic education in enmaen tradition toward Madurese in Suka Maju village, Sungai Ambawang district. Karsa J. Soc. Islam. Cult. 2019, 27, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, F.; Sirajul, A. The ethno-ethics of tanean lanjheng: Business ethos construction of a Madurese Muslim family. Lisan Al-Hal J. Pengemb. Pemikir. Dan Kebud. 2020, 14, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayatillah, Y. The relationship comparation of tanèyan lanjháng in Madura community. J. Ilm. Pendidik. Pancasila Dan Kewarganegaraan 2017, 2, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Febrianto, R.; Wulandari, L.; Santosa, H. Landscape agriculture expression and settlement patterns of the farmer in east Madura. Rev. Urban. Archit. Stud. 2016, 14, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzia, L.; Ari, I.R.D.; Hariyani, S. Characteristics of the taneyan lanjhang settlement in the district of Labang, Madura (case study in Jukong and Labang village). Arsit. E-J. 2009, 2, 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Dewi, F.P.R.; Antariksa. Surjono Conservation of taneyan lanjhang housing patterns in settlements in Lombang village, Sumenep regency. Arsit. E-J. 2008, 1, 94–109. [Google Scholar]

- Safeyah, M.; Elviana, E.; Takarini, N.; Sutejo, A. The changes of the spatial pattern of tanean lanjang in kampung batik Tanjung Bumi. Tesa Arsit. 2018, 16, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tulistyantoro, L. The Meaning Space of Tanean Lanjang in Madura. Dimens. Inter. 2005, 3, 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Noer, K.U. Land, marriage and social exclusion: The case of Madurese exile widow. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 65, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srilestari, R.N. Thermal comfort and Madurese traditional house in Sumenep. J. Archit. Environ. 2005, 4, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kehlenbeck, K.; Maass, B.L. Crop diversity and classification of homegardens in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. Agrofor. Syst. 2004, 63, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paembonan, S.A.; Millang, S.; Dassir, M.; Ridwan, M. Species variation in home garden agroforestry system in South Sulawesi, Indonesia and its contribution to farmers’ income. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 157, 12004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyoutami, E.; Rismawan, R.; Joshi, L. Local knowledge and management of simpukng (forest gardens) among the Dayak people in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 2054–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahu, A.A.; Hidayat, K.; Ariyadi, M.; Hakim, L. Ethnoecology of Kaleka: Dayak’s agroforestry in Kapuas, Central Kalimantan Indonesia. Res. J. Agric. For. Sci 2013, 1, 2320–6063. [Google Scholar]

- Rahu, A.A.; Hidayat, K.; Ariyadi, M.; Hakim, L. Management of Kaleka (traditional gardens) in Dayak community in Kapuas, Central Kalimantan. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2014, 3, 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Sujarwo, W.; Caneva, G. Ethnobotanical study of cultivated plants in home gardens of traditional villages in Bali (Indonesia). Hum. Ecol. 2015, 43, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darma, I.D.P.; Sutomo, S.; Hanum, S.F.; Iryadi, R. Plant conservation based on tri mandala concept on homegarden at Pakraman Penge village, Baru village, Marga district, Tabanan regency, Bali. J. Trop. Biodivers. Biotechnol. 2020, 5, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silalahi, M.; Nisyawati, N. The ethnobotanical study of edible and medicinal plants in the home garden of Batak Karo sub-ethnic in north Sumatra, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2018, 19, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swandayani, R.E.; Hakim, L.; Indriyani, S. Home garden of Sasak people in Sajang village, Sembalun, East Lombok, Indonesia. Int. J. Res. Stud. Agric. Sci. 2016, 2, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, L.; Kee, H. Home garden of local community in Pancasila village for biodiversity conservation and ecotourism sites development in Tambora Geopark, Sumbawa Island. J. Trop. Life Sci. 2018, 8, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hakim, L.; Nakagoshi, N. Plant species composition in home gardens in the Tengger highland (East Java, Indonesia) and its importance for regional ecotourism planning. Hikobia 2007, 15, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pamungkas, R.N.; Indriyani, S.; Hakim, L. The ethnobotany of homegardens along rural corridors as a basis for ecotourism planning: A case study of Rajegwesi village, Banyuwangi, Indonesia. J. Biodivers. Environ. Sci. 2013, 3, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim, L.; Pamungkas, N.R.; Wicaksono, K.P.; Soemarno, S. The conservation of Osingnese traditional home garden agroforestry in Banyuwangi, East Java, Indonesia. Agrivita 2018, 40, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoellah, O.S.; Schneider, M.; Nugraha, L.M.; Suparman, Y.; Voletta, C.T.; Withaningsih, S.; Parikesit; Heptiyanggit, A.; Hakim, L. Homegarden commercialization: Extent, household characteristics, and effect on food security and food sovereignty in Rural Indonesia. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochana, T. Madurese people: An anthropological review. Hum. J. Ilm. Ilmu-Ilmu Hum. 2012, 11, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Pandiangan, D.; Silalahi, M.; Dapas, F.; Kandou, F. Diversity of medicinal plants and their uses by the Sanger tribe of Sangihe Islands, North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2019, 20, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rifai, M.A. Madurese Man: Demenor, Behavior, Work Ethic, Appearance, and Outlook on Live as Imaged by the Proverb; Pilar Media: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2007; ISBN 9793921463. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayah, N.; Ramli, M. Need of cognitive-behavior counseling model based on local wisdom to improve meaning of life of Madurese culture junior high school students. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res. 2017, 128, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- BPS (Indonesia Statistic Government Office). East Java Province in Figures 2021; BPS-East Java Province: Surabaya, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- BPS (Indonesia Statistic Government Office). Bangkalan Regency in Figures 2021; BPS-Statictics of Bangkalan Regency: Bangkalan, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- BPS (Indonesia Statistic Government Office). Sampang Regency in Figures 2021; BPS-Statictics of Sampang Regency: Sampang, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- BPS (Indonesia Statistic Government Office). Pamekasan Regency in Figures 2021; BPS-Statictics of Pamekasan Regency: Pamekasan, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- BPS (Indonesia Statistic Government Office). Sumenep Regency in Figures 2021; BPS-Statictics of Sumenep Regency: Sumenep, Indonesia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vogl, C.R.; Vogl-Lukasser, B.; Puri, R.K. Tools and methods for data collection in ethnobotanical studies of homegardens. Field Methods 2004, 16, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, C. Cuban home gardens and their role in social-ecological resilience. Hum. Ecol. 2009, 37, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, B.N.; Medley, K.E. Home gardenscapes as sustainable landscape management on St. Eustatius, Dutch Caribbean. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Plantlist. The Plantlist Database. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden. 2021. Available online: http://www.theplantlist.org/ (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Idohou, R.; Fandohan, B.; Salako, V.K.; Kassa, B.; Gbèdomon, R.C.; Yédomonhan, H.; Kakaï, R.L.G.; Assogbadjo, A.E. Biodiversity conservation in home gardens: Traditional knowledge, use patterns and implications for management. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2014, 10, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Luo, B.; La, B.; Chen, R.; Liu, F.; Long, C. Homegarden agroecosystems managed by Salar people on Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pala, N.A.; Sarkar, B.C.; Shukla, G.; Chettri, N.; Deb, S.; Bhat, J.A.; Chakravarty, S. Floristic composition and utilization of ethnomedicinal plant species in home gardens of the Eastern Himalaya. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonen, T.; Giday, M.; Kelbessa, E. Ethnobotanical study of homegarden plants in Sebeta-Awas District of the Oromia Region of Ethiopia to assess use, species diversity and management practices. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefera, Y.; Babu, A.; Bizuayehu, B. Homegarden plant use and their traditional management practice in Bule Hora district, West Guji Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Agric. Res. Technol. 2019, 21, 556168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapsari, L.; Masrum, A.; Lestari, D.A. Diversity of bananas (Musa spp.) in Madura island, East Java: Exploration and inventory. J. Biodivers. Environ. Sci. 2015, 6, 256–264. [Google Scholar]

- Kilwinger, F.B.M.; Rietveld, A.M.; Groot, J.C.J.; Almekinders, C.J.M. Culturally embedded practices of managing banana diversity and planting material in central Uganda. J. Crop Improv. 2019, 33, 456–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwardi, A.B.; Navia, Z.I.; Harmawan, T.; Syamsuardi, S.; Mukhtar, E. The diversity of wild edible fruit plants and traditional knowledge in West Aceh region, Indonesia. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2019, 7, 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Wakhidah, A.Z.; Sari, I.A. Ethnobotany of home garden in West Kaliurang, Pakem, Sleman, Yogyakarta. J. EduMatSains 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sari, F.M.W.; Adi, A.C. Food Security and Coping Strategy of Households on the Gili Labak Isolated Island, Sumenep Regency Madura. Media Gizi Indones. 2018, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, E.; Stacey, N.; Sunderland, T.C.H.; Adhuri, D.S. Dietary diversity and fish consumption of mothers and their children in fisher households in Komodo District, eastern Indonesia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, S.B.; Bajagain, A. Moringa: Alternative for the food security, climate resilience and livelihood improvement in Nepal. Int. J. Res. Granthalayah 2020, 8, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, A.; Goshu, D.; Gelaw, F.; Ademe, A. Food and nutrition security impacts of Moringa: Evidence from Southern Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 2020, 6, 1733330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milla, P.G.; Peñalver, R.; Nieto, G. Health benefits of uses and applications of moringa oleifera in bakery products. Plants 2021, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Z.; Islam, S.M.R.; Hossen, F.; Mahtab-Ul-Islam, K.; Hasan, M.R.; Karim, R. Moringa oleifera is a Prominent Source of Nutrients with Potential Health Benefits. Int. J. Food Sci. 2021, 2021, 6627265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.K.; Chowdhury, A.; Das, J.; Roy, A.; Hosen, S.Z. Pharmacological potentials of Moringa oleifera lam.: A Review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2012, 3, 305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Indonesia Ministry of Agriculture Directorate General of Horticulture. Strategic Planning of Horticulture Directorate General 2020–2024; Indonesia Ministry of Agriculture Directorate General of Horticulture: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leliqia, N.P.E.; Wardani, N.K.S.L.A. A review of phytochemical and pharmacological studies of Piper retrofractum Vahl. J. Pharm. Sci. Appl. 2021, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evizal, R. Development of pharmacognosy and agrotechnology of Java long pepper (Piper Retrofractum Vahl.). J. Agrotropika 2014, 18, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Widana, I.N.S. Etnobotani Tabia bun (Piper retrofractum Vhal.) (Kajian Teoritik). J. Emasains 2021, 10, 2124. [Google Scholar]

- Purwanti, E.; Mahmudati, N.; Faradila, S.F.; Fauzi, A. Utilization of plants as traditional medicine for various diseases: Ethnobotany study in SUmeNep, Indonesia. AIP Conf. Proc. 2020, 2231, 40024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadid, N.; Kurniawan, E.; Himayani, C.E.S.; Andriyani; Prasetyowati, I.; Purwani, K.I.; Muslihatin, W.; Hidayati, D.; Tjahjaningrum, I.T.D. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the Tengger tribe in Ngadisari village, Indonesia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathir, A.; Haikal, M.; Wahyudi, D. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used for maintaining stamina in madura ethnic, East Java, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2021, 22, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosoky, N.S.; Setzer, W.N. Chemical composition and biological activities of essential oils of curcuma species. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoellah, O.S.; Parikesit; Okubo, S.; Withaningsih, S.; Takeuchi, K.; Mizuno, K. Perceptions of owners on the roles and future of bamboo-tree gardens in the agricultural landscape of the Upper Citarum Basin, West Java-Indonesia. Agric. Sci. 2015, 6, 1333–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaneckas, K.; Adamavičiene, A.; Šarauskis, E.; Balandaite, J. The impact of intercropping on soil fertility and sugar beet productivity. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christanty, L.; Abdoellah, O. Traditional agroforestry in West Java: The pekarangan (homegarden) and kebun-talun (annual-perennial rotation) cropping systems. Tradit. Agric. Southeast Asia 1986, 6, 132–158. [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan, E. The local wisdom of pattern intercropping systems in East Java. Agrovigor 2009, 2, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Vávra, J.; Smutná, Z.; Hruška, V. Why i would want to live in the village if i was not interested in cultivating the plot? A study of home gardening in rural czechia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V.; Aceituno, L.; Vila, S.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Garnatje, T.; Jesch, A.; Lastra, J.J.; Parada, M.; Rigat, M.; Vallès, J.; et al. Home Gardens in Three Mountain Regions of the Iberian Peninsula: Description, Motivation for Gardening, and Gross Financial Benefits. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvet-Mir, L.; March, H.; Corbacho-Monné, D.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Reyes-García, V. Home garden ecosystem services valuation through a gender lens: A case study in the Catalan Pyrenees. Sustainability 2016, 8, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, J.A.; Leung, C.W. Food insecurity and COVID-19: Disparities in early effects for us adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, R.-F.; Liu, C.-F.; Gao, J.-J.; Wang, T.-Y.; Zhi, H.-Y.; Shi, P.-F.; Huang, J.-K. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on rural poverty and policy responses in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2946–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsahoryi, N.; Al-Sayyed, H.; Odeh, M.; McGrattan, A.; Hammad, F. Effect of COVID-19 on food security: A cross-sectional survey. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 40, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhwani, V.; Deshkar, S.; Shaw, R. COVID-19 lockdown, food systems and urban–rural partnership: Case of Nagpur, India. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, R. Home gardening and urban agriculture for advancing food and nutritional security in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Serrano, V.; Onaindia, M.; Alday, J.G.; Caballero, D.; Carrasco, J.C.; McLaren, B.; Amigo, J. Plant diversity and ecosystem services in Amazonian homegardens of Ecuador. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 225, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, A.R.; Sahoo, U.K.; Upadhyaya, K. Plant Diversity in the Indigenous Home Gardens in the Eastern Himalayan Region of Mizoram, Northeast India. Econ. Bot. 2016, 70, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peroni, N.; Hanazaki, N.; Begossi, A.; Zuchiwschi, E.; Lacerda, V.D.; Miranda, T.M. Homegardens in a micro-regional scale: Contributions to agrobiodiversity conservation in an urban-rural context. Ethnobiol. Conserv. 2016, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, T.R.; Koestiono, D.; Setiawan, B.; Nugroho, B.A. Upgrading value chain strategy for beef cattle in Madura Island, East Java. PalArch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt 2020, 17, 9495–9504. [Google Scholar]

- Widi, T.S.M.; Udo, H.M.J.; Oldenbroek, K.; Budisatria, I.G.S.; Baliarti, E.; van der Zijpp, A.J. Unique cultural values of Madura cattle: Is cross-breeding a threat? Anim. Genet. Resour. Génétiques Anim. Genéticos Anim. 2014, 54, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohri, H.; Lahoti, S.; Saito, O.; Mahalingam, A.; Gunatilleke, N.; Irham; Hoang, V.T.; Hitinayake, G.; Takeuchi, K.; Herath, S. Assessment of ecosystem services in homegarden systems in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam. Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 5, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, S.S.; Siebert, S.J.; Du Toit, M.J.; Barthel, S.; Mishra, S.; Cornelius, S.F.; Davoren, E. Garden ecosystem services of Sub-Saharan Africa and the role of health clinic gardens as social-ecological systems. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | <30 | 10.0 |

| 30–60 | 74.5 | |

| >60 | 15.5 | |

| Sex | Male | 63.4 |

| Female | 36.6 | |

| Status | Single | 10.0 |

| Married | 78.5 | |

| Widow/widower | 11.5 | |

| Education level | No education | 12.5 |

| Elementary school | 69.0 | |

| Junior high school | 9.5 | |

| Senior high school | 7.8 | |

| University | 1.3 | |

| Occupation | Farmer | 100.0 |

| Religion | Islam/Muslim | 100.0 |

| Family members | 1–4 | 80.5 |

| >4 | 19.5 | |

| <100 | 34.2 | |

| Monthly income (USD) | 100–145 | 65.8 |

| >145 | 34.2 | |

| No. | Element | Description, Function and Philosophy |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |  Roma (house) |

|

| 2 |  Kobung/langgar (mosque) |

|

| 3 |  Dapor (kitchen) |

|

| 4 |  Kandang (cage) |

|

| 5 |  Taneyan (yard) |

|

| 6 |  Natural/organic fence |

|

| 7 |  Warehouse |

|

| 8 |  Well and water reservoir |

|

| 9 |  Outdoor bathroom |

|

| Species | Occurrence No. | Relative Frequency/RF (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Musa spp. | 196 | 98.0 |

| Mangifera indica L. | 175 | 87.5 |

| Zea mays L. | 155 | 77.5 |

| Manihot esculenta Crantz | 152 | 76.0 |

| Bambusa glaucescens (Willd.) Merr. | 150 | 75.0 |

| Moringa oleifera Lam. | 145 | 72.5 |

| Capsicum frutescens L. | 138 | 69.0 |

| Piper retrofractum Vahl | 129 | 64.5 |

| Curcuma longa L. | 125 | 62.5 |

| Arachis hypogaea L. | 123 | 61.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Setiani, S.; Setiawan, E.; Huang, W.-C. Taneyan Lanjang Shared Home Gardens and Sustainable Rural Livelihoods of Ethnic Madurese in Madura Island, Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5960. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105960

Setiani S, Setiawan E, Huang W-C. Taneyan Lanjang Shared Home Gardens and Sustainable Rural Livelihoods of Ethnic Madurese in Madura Island, Indonesia. Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):5960. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105960

Chicago/Turabian StyleSetiani, Setiani, Eko Setiawan, and Wen-Chi Huang. 2022. "Taneyan Lanjang Shared Home Gardens and Sustainable Rural Livelihoods of Ethnic Madurese in Madura Island, Indonesia" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 5960. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105960

APA StyleSetiani, S., Setiawan, E., & Huang, W.-C. (2022). Taneyan Lanjang Shared Home Gardens and Sustainable Rural Livelihoods of Ethnic Madurese in Madura Island, Indonesia. Sustainability, 14(10), 5960. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105960