What Influences Attitudes and Confidence in Teaching Physics and Technology Topics? An Investigation in Kindergarten and Primary-School Trainee Teachers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Background and Prior Research on “General Knowledge”

1.2. Theoretical Background and Prior Research on “Vocational Interest”

1.3. Theoretical Background and Prior Research on the “Big-Five” Personality Traits

1.4. Research Rationale, Aims and Questions of This Study

- ▪

- How did trainee teachers assess their confidence in teaching physics and technology, and what were their self-assessments in regard to teaching other topics in social and natural sciences? How did they rank by popularity physical and technical teaching topics in a series of natural and social sciences topics? Which characteristics of general knowledge, vocational interest, and personality were related to trainee teachers’ confidence and attitudes towards teaching physics and technology?

- ▪

- How and what aspects of general knowledge, vocational interest, and personality did trainee teachers who favoured teaching physics and technology differ from trainee teachers who did not? Which subgroup-specific relationships were found in the subsamples?

- ▪

- How and what aspects of general knowledge and personality did trainee teachers with an interest profile typical for kindergarten and primary-school teachers differ from trainee teachers with an interest profile that was considered more suitable for physics and technology teaching? Which subgroup specific relationships were found in the subsamples?

- ▪

- Which of the assumed influence factors (general knowledge, vocational interest, and personality) could accurately predict trainee teachers’ confidence? Were there differences in those influences depending on the group affiliations?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Measuring Instruments

2.3.1. The Nature–Human–Society Questionnaire (In German: Natur–Mensch–Gesellschaft Fragebogen, i.e., NMG Questionnaire)

2.3.2. General Knowledge Test (In German: Bochumer Wissenstest, i.e., BOWIT)

2.3.3. General Interest Structure Test, Revised (In German: Allgemeiner Interessen-Struktur-Test, Revised, i.e., AIST-R)

2.3.4. Big Five Inventory 10 (BFI-10)

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

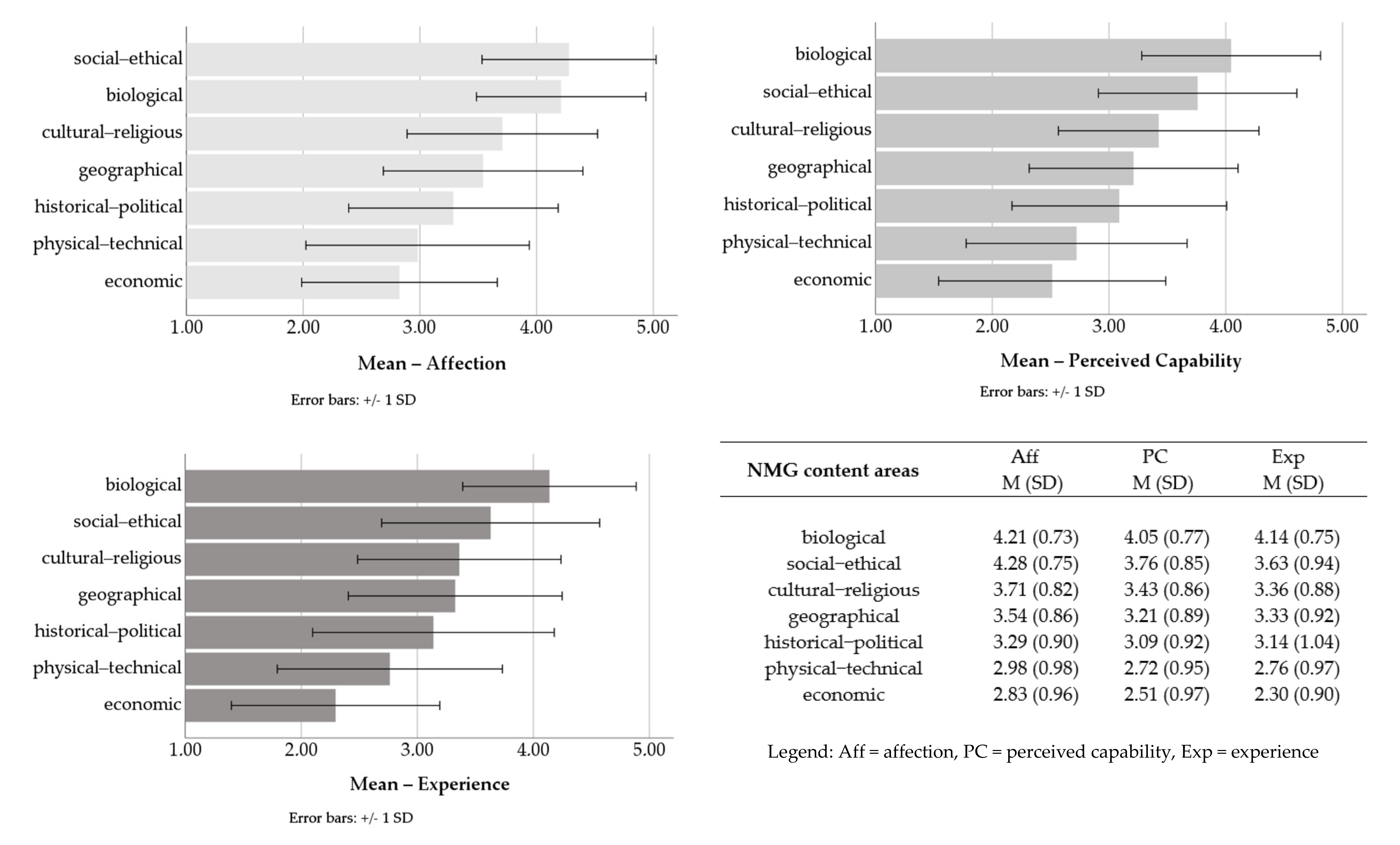

3.1.1. The Samples’ Affection, Perceived Capability, and Experience Regarding Different NMG-Content Areas: Results of the NMG Questionnaire

3.1.2. The Samples’ General Knowledge: The Results of BOWIT

3.1.3. The Samples’ Vocational Interests: The Results of AIST-R

3.1.4. The Samples’ Personality Traits: Results of BFI-10

3.2. Correlations

3.2.1. NMG Physical–Technical Scores and General Knowledge (BOWIT)

3.2.2. NMG Physical–Technical Scores and Vocational Interests (AIST-R)

3.2.3. NMG Physical–Technical Scores and Personality Traits (BFI-10)

3.2.4. Correlations Separated by the Sub-Samples with and without Physics and Technology as Favoured Content to Teach

3.2.5. Correlations Separated by the Interest-Profile Groups SAE and SI

3.3. Group Differences and Discriminant Analysis

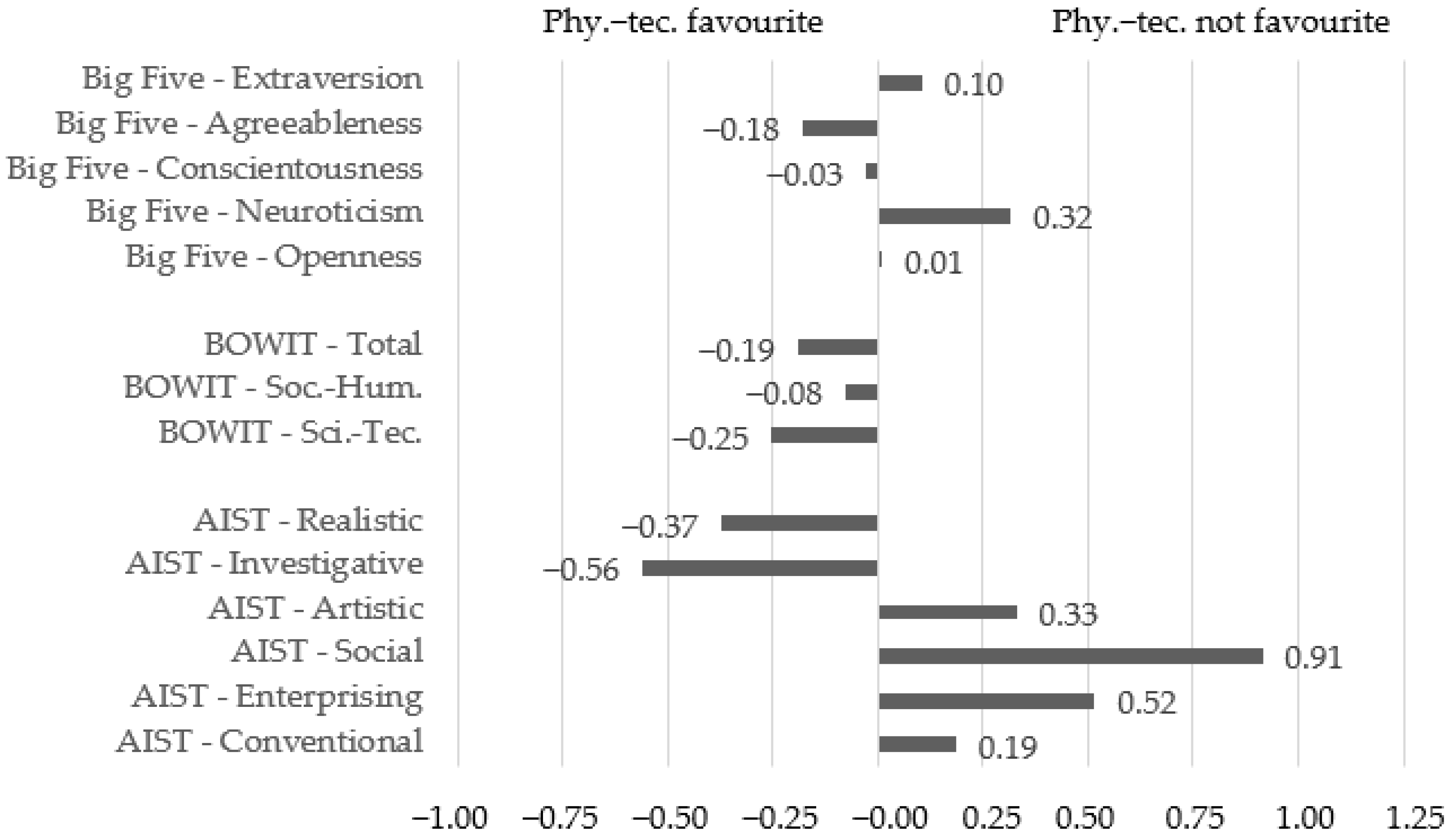

3.3.1. Differences between Groups with and without Physics and Technology as Favourite Content to Teach

3.3.2. Discriminant Analysis: Allocation to the Groups with and without Physics and Technology as Favoured Content to Teach

3.3.3. Differences between the SAE and SI Interest-Profile Groups

3.4. Linear Regression Analyses: Which Variables Are Able to Predict Whether Anyone Has a High or Low Perceived Capability in the Physical–Technical Area?

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Appleton, K. Student teacher’s Confidence to Teach Science: Is more science knowledge necessary to improve self-confidence? Int. J. Sci. Educ. 1995, 17, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D.H. Durability of Changes in Self-Efficacy of Preservice Primary Teachers. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2006, 28, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, T. The Beliefs of Preservice Primary Teachers Towards Science and Science Teaching. Sch. Sci. Math. 2000, 100, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, O.S. Science Interest and Confidence Among Preservice Elementary Teachers. J. Elem. Sci. Educ. 1999, 11, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendergast, E.; Lieberman-Betz, R.G.; Vail, C.O. Attitudes and Beliefs of Prekindergarten Teachers Toward Teaching Science to Young Children. Early Child. Educ. J. 2017, 45, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, N.; Lankes, E.-M.; Steffensky, M. Vorstellungen von pädagogischen Fachkräften zum Lernen von Naturwissenschaften. In Lernen und Lehren im Sachunterricht: Zum Verhältnis von Konstruktion und Instruktion; Giest, H., Heran-Dörr, E., Archie, C., Eds.; Klinkhardt: Bad Heilbrunn, Germany, 2012; pp. 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Van Aalderen-Smeets, S.; van der Molen, J.W.; Asma, L.J.F. Primary Teacher’s Attitudes Toward Science: A New Theoretical Framework. Sci. Educ. 2012, 35, 577–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacieminoglu, E. Elementary School Students’ Attitude Toward Science and Related Variables. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2016, 11, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pahl, A. Teaching Physics in Kindergarten and Primary School: What do Trainee Teachers Think of This? GIREP Springer Book 2022. accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, K. How Do Beginning Primary School Teachers Cope with Science? Toward an Understanding of Science Teaching Practice. Res. Sci. Educ. 2003, 33, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.M.; Dragsted, S.; Evans, R.H.; Sørensen, H. The Relationship Between Changes in Teacher’s Self-efficacy Beliefs and the Science Teaching Environment of Danish First-Year Elementary Teachers. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2004, 15, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlen, W.; Holroyd, C. Primary Teachers’ Understanding of Concept of Science: Impact on Confidence and Teaching. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 1997, 19, 19–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencze, L.; Hodson, D. Changing Practice by Changing Practice: Toward More Authentic Science and Science Curriculum Development. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1999, 36, 521–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleickmann, T. Professionelle Kompetenz von Primarschullehrkräften im Bereich des naturwissenschaftlichen Sachunterrichts. Z. Grund. 2015, 8, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Slupina, M.; Klingholz, R. Bildung von klein auf sichert Zukunft. Warum frühkindliche Förderung entscheidend ist; Berlin Institut für Bevölkerung und Entwicklung: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wößmann, L. Efficiency and Equity of European Education and Training Policies. Int. Tax Public Financ. 2008, 15, 199–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K.; Shumow, L.; Lietz, S. Science Education in an Urban elementary School: Case Studies of Teacher Beliefs and Classroom Practices. Sci. Educ. 2001, 85, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazempour, M. I can’t Teach Science! A Case Study of an Elementary Pre-Service Teachers’ Intersection of Science Experience, Beliefs, Attitude, and Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2014, 9, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acatech; Koerber Stiftung. MINT-Nachwuchsbarometer 2021; Gutenberg Beuys Feindruckerei: Hannover, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Akademien der Wissenschaften Schweiz. MINT-Nachwuchsbarometer Schweiz—Das Interesse von Kindern und Jugendlichen an naturwissenschaftlich-technischer Bildung. Swiss Acad. Rep. 2014, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lück, G. Naturwissenschaften im frühen Kindesalter. Untersuchungen zur Primärbegegnung von Kindern im Vorschulalter mit Phänomen der unbelebten Natur; Lit: Münster, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Smorti, M.; Tschiesner, R.; Farneti, A. Grandparents-grandchildren relationship. Procedica Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 895–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.; Vaughan, G. Social Psychology, 4th ed.; Prentice-Hall: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stangor, C.; Jhangiani, R.; Tarry, H. Principles of Social Psychology, 1st international ed.; BCampus OpenEd: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, C.H. Self Concept Content. In Encyclopaedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 4682–4685. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrake, R. Confidence as Motivational Expressions of Interest, Utility, and other Influences: Exploring Under-Confidence and Over-Confidence in Science Students at Secondary School. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 76, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bong, M.; Skaalvik, E.M. Academic Self-concept and Self-efficacy: How different are they really? Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 19, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, E.; Ng, P.; Hui, C.; Cai, L. How Do Teacher Affective and Cognitive Self-Concepts Predict Their Willingness to Teach Challenging Students? Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2019, 44, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Green, J. The Causal Ordering of Self-concept and Academic Motivation and its Effect on Academic Achievement. Int. Educ. J. 2006, 7, 534–546. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy—The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Abood, M.H.; Alharbi, B.H.; Mhaidat, F.; Gazo, A.M. The Relationship between Personality Traits, Academic Self-Efficacy and Academic Adaption among University Students in Jordan. Int. J. High. Educ. 2020, 9, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Larkin, K.C. Relation of Self-Efficacy to Inventoried Vocational Interests. J. Vocat. Behav. 1989, 34, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senler, B.; Sungur-Vural, S. Pre-Service Science Teacher’s Teaching Self-Efficacy in Relation to Personality Traits and Academic Self-Regulation. Span. J. Psychol. 2013, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tschiesner, R.; Pahl, A. Trainee Teachers’ Preferences in the Subject ‘Human-Nature-Society’: The Role of Knowledge. ICERI Proc. 2019, 12, 3167–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, E.; Fraenz, C.; Schlüter, C.; Friedrich, P.; Voelkle, M.C.; Hossiep, R.; Güntürkün, O. The Neural Architecture of General Knowledge. Eur. J. Personal. 2019, 33, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonitz, V.S.; Armstrong, P.I.; Larson, L.M. Geschlechterunterschiede im Allgemeinwissen—die Folge geschlechtsspezifischer Berufsinteressen. In Allgemeinbildung in Deutschland: Erkenntnisse aus dem SPIEGEL-Studentenpisa-Test; Trepte, S., Verbeet, M., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; pp. 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- Hossiep, R.; Schulte, M. Bochumer Wissenstest; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell, R.B. Intelligence: Its Structure, Growth, and Action; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell, R.B. Theory of Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence: A Critical Experiment. J. Educ. Psychol. 1963, 54, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossiep, R.; Schulte, M.; Frieg, P. Was ist Wissen—und wie lässt es sich messen. In Allgemeinbildung in Deutschland: Erkenntnisse aus dem SPIEGEL-Studentenpisa-Test; Trepte, S., Verbeet, M., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman, P.L.; Rolfhus, E. The Locus of Adult Intelligence: Knowledge, Abilities, and Nonability Traits. Psychol. Aging 1999, 14, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, P.L. A Theory of Adult Intellectual Development: Process, Personality, Interests, and Knowledge. Intelligence 1996, 22, 227–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, P.L.; Beier, M.E. Knowledge and Intelligence. In Handbook of Understanding and Measuring Intelligence; Wilhelm, O., Ed.; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Woolfolk, A. Pädagogische Psychologie, 10th ed.; Pearson Studium: München, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Renner, W.; Maier, M.J. Deutschland klügste Köpfe: Was die Herkunft und Hauptfach über das Allgemeinwissen aussagen. In Allgemeinbildung in Deutschland: Erkenntnisse aus dem SPIEGEL-Studentenpisa-Test; Trepte, S., Verbeet, M., Eds.; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; pp. 177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, A.; Giesen, H. Leistungsvoraussetzungen und Studienbedingungen bei Studierenden verschiedener Lehrämter. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht 1993, 40, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ineson, E.M.; Jung, T.; Hains, C.; Kim, M. The Influence of Prior Subject Knowledge, Prior Ability and Work Experience on Self-Efficacy. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2013, 12, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.; Byrne, B.M.; Shavelson, R.J. A Multifaceted Academic Selfconcept: Its Hierarchical Structure and its Relation to Academic Achiecement. J. Educ. Psychol. 1988, 80, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Das Konzept der Selbstwirksamkeit. In Selbstwirksamkeit und Motivationsprozesse in Bildungsinstitutionen; Jerusalem, M., Hopf, D., Eds.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2002; pp. 28–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Interest and Effort in Education (1913); Classical Reprint; Kessinger Publishing: Whitefish, MT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cattel, R.B. The Description of Personality: Basic Traits Resolved Into Clusters. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1943, 38, 476–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, C.L.; Hakel, M.D. Toward an understanding of adult intellectual development: Investigating within-individual conver-gence of interest and knowledge profiles. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, C.; Eder, F. Allgemeiner Interessen-Struktur-Test mit Umwelt-Struktur-Test (UST-R); Revision; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.L. Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of Vocational Personalities and Work Environments, 3rd ed.; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, Ukraine, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Krapp, A.; Hidi, S.; Ann Renninger, K. Interest, Learning, And Development. In The Role of Interest in Learning and Development; Renninger, K.A., Hidi, S., Krapp, A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Prediger, D.J. Dimensions Underlying Holland’s Hexagon: Missing Link Between Interests and Occupations? J. Vocat. Behav. 1982, 21, 259–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, F.; Bergmann, C. Das Personen-Umwelt-Modell von J. L. Holland: Grundlagen—Konzepte—Anwendungen. In Berufliche Interessen. Beiträge zur Theorie von J. L. Holland; Tarnai, C., Hartmann, F.G., Eds.; Waxmann Verlag: Münster, Germany, 2015; pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Klusmann, U.; Trautwein, U.; Lüdtke, O.; Kunter, M.; Baumert, J. Eingangsvoraussetzungen beim Studienbeginn: Werden die Lehramtskandidaten unterschätzt? Z. Pädagogische Psychol. 2009, 23, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henoch, J.R.; Klusmann, U.; Lüdtke, O.; Trautwein, U. Who Becomes a Teacher? Challenging the “Negative Selection” Hypothesis. Learn. Instr. 2015, 36, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookhart, S.M.; Freeman, D.J. Characteristics of Entering Teacher Candidates. Rev. Educ. Res. 1992, 62, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaub, K.; Karbach, J.; Biermann, A.; Friedrich, A.; Bedersdorfer, H.-W.; Spinath, F.M. Berufliche Interessensorientierung und kognitive Leistungsprofile von Lehramtsstudierenden mit unterschiedlichen Fachkombinationen. Z. Pädagogische Psychol. 2012, 26, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, A.; Behrendt, S.; Nickolaus, R. Interessenstrukturen von Studierenden und damit verbundene Potentiale für die Gewinnung von Lehramtsstudierenden. J. Tech. Educ. 2018, 6, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerster, F. Personale Voraussetzungen von Grundschullehramtsstudierenden: Eine Untersuchung zur prognostischen Relevanz von Persönlichkeitsmerkmalen für den Studien- und Berufserfolg; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Sheu, H.-B. The Self-Efficacy-Interest Relationship and RIASEC Types: Which Is Figure and Which Is Ground? Comment on Armstrong and Vogel. J. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 57, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuutila, K.; Tabola, A.; Tuominen, H.; Kupiainen, S.; Pásztor, A.; Niemivirta, M. Reciprocal Predictions Between Interest, Self-Efficacy, and Performance During a Task. Front. Educ. 2020, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krapp, A. Interest, Motivation and Learning: An Educational-Psychological Perspective. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 1999, 14, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.W.; Jackson, J.J. Sociogenomic Personality Psychology. J. Personal. 2008, 76, 1523–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McCrae, R.; Costa, P.T. A Five-Factor Theory of Personality. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 2nd ed.; Pervin, L.A., John, O.P., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Stemmler, G.; Hagemann, D.; Amelang, M.; Spinath, F.M. Differentielle Psychologie und Persönlichkeitsforschung, 8th ed.; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2016; pp. 293–307. [Google Scholar]

- Seegers, P.; Bergerhoff, J.; Knappe, S. Fachkraft 2020: 7. und 8. Erhebung zur wirtschaftlichen und allgemeinen Lebenssituation der Studierenden in Deutschland; Studitemps GmBH, Maastricht University, Eds.; Studitemps: Köln, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, D. The Personality of Physicists Measured. Am. Sci. 1994, 82, 324–325. [Google Scholar]

- Koschmieder, C.; Weissenbacher, B.; Pertsch, J.; Neubauer, A. The Impact of Personality in the Selection of Teacher Students: Is There More to it Than the Big Five? Eur. J. Psychol. 2018, 14, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Usslepp, N.; Hübner, N.; Stoll, G.; Spengler, M.; Trautwein, U.; Nagengast, B. RIASEC Interests and the Big Five Personality Traits Matter for Life Success—But do they Already Matter for Educational Track Choices? J. Personal. 2020, 8, 1007–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.M.; Rottinghaus, P.J.; Borgen, F.H. Meta-Analyses of Big Six Interests and Big Five Personality Factors. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, G.D.; Jones, E.M.; Holland, J.L. Personality and Vocational Interests: The Relation of Holland’s Six Interest Dimensions to Five Dimensions of Personality. J. Couns. Psychol. 1993, 40, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bipp, T. Persönlichkeit—Ziele—Leistung. Der Einfluss der Big Five auf das zielbezogene Leistungshandeln. Phd Thesis, Technische Universität, Dortmund, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smidt, W.; Kammermexer, G.; Roux, S.; Theisen, C.; Weber, C. Career Success of Preschool Teachers in Germany—The Significance of the Big Five Personality Traits, Locus of Control, and Occupational Self-Efficacy. Early Child Dev. Care 2018, 188, 1340–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Döring, N.; Bortz, J. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl, A.; Tschiesner, R.; Adamina, M. The ‘Nature-Human-Society’-Questionnaire for Kindergarten and Primary School Trainee Teachers: Psychometric Properties and Validition. ICERI Proc. 2019, 12, 3196–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B.; Kemper, C.J.; Klein, M.C.; Beierlein, C.; Kovaleva, A. Eine kurze Skala zur Messung der fünf Dimensionen der Persönlichkeit. 10 Item Big Five Inventory (BFI-10). Methoden Daten Anal. 2013, 7, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.R. Language and Individual Differences: The Search for Universals in Personality Lexicons. In Review of Personality and Social Psychology; Wheeler, L., Ed.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1981; pp. 141–165. [Google Scholar]

- John, O.P.; Donahue, E.M.; Kentle, R.L. The Big Five Inventory; Versions 4a and 54; Institute of Personality and Social Research, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bühner, M. Einführung in die Test- und Fragebogenkonstruktion, 2nd ed.; Pearson: München, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus, K.; Erichson, B.; Plincke, W.; Weiber, R. Multivariate Analysemethoden. Eine anwendungsorientierte Einführung; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bortz, J.; Schuster, C. Statistik für Human- und Sozialwissenschaftler, 7th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bühner, M.; Ziegler, M. Statistik für Psychologen und Sozialwissenschaftler, 2nd ed.; Pearson: Hallbergmoos, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gashemi, A.; Zahediasl, S. Normality Tests for Statistical Analysis: A Guide for Non-Statisticians. Int. J. Endocrinololgy Metab. 2012, 10, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An Analysis of Variance of Normality. Biometrika 1965, 52, 561–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasch, D.; Guiard, V. The Robustness of Parametric Statistical Methods. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 46, 175–208. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, B.S.; Kozolowski, S.W.J. Goal Orientation and Ability: Interactions Effects on Self-Efficacy, Performances, and Knowledge. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fuchs, H.U.; Corni, F.; Pahl, A. Embodied Simulations of Forces of Nature and the Role of Energy in Physical Systems. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschiesner, R.; Farneti, A. Clowning Training to Improve Working Conditions and Increase the Well-being of Employees. In Arts-Based Research, Resilience and Well-Being across the Lifespan; McCain, L., Barton, G., Garvis, S., Sappa, V., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2000; pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity and the Life Cycle; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

| Total Sample (n = 196) | Phy.–Techn. not Favourite (n = 147) | Phy.–Techn. Favourite (n = 49) | Interest Profile SAE (n = 65) | Interest Profile SI (n = 67) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMG—physical–technical | Aff | PC | Exp | Aff | PC | Exp | Aff | PC | Exp | Aff | PC | Exp | Aff | PC | Exp |

| Big5—Extraversion | −0.10 | −0.14 * | −0.14 * | −0.10 | −0.11 | −0.15 + | −0.04 | −0.14 | −0.06 | −0.15 | −0.29 * | −0.22 + | 0.08 | −0.06 | −0.12 |

| Big5—Agreeableness | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.09 | −0.14 + | −0.04 | −0.13 | 0.01 | −0.13 | −0.06 | −0.30 * | −0.06 | −0.15 | −0.17 | −0.13 | −0.25 * |

| Big5—Conscientiousness | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.16 | −0.13 | −0.12 | −0.17 | −0.02 |

| Big5—Neuroticism | −0.11 | −0.20 ** | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.15 + | −0.02 | −0.30 * | −0.22 | −0.18 | −0.21 + | −0.21 + | −0.08 | −0.13 | −0.23 + | −0.05 |

| Big5—Openness | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.09 | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.11 | −0.11 |

| BOWIT—Total | 0.15 * | 0.15 * | 0.17 * | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.39 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.39 ** | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.02 | 0.32 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.31 * |

| BOWIT—Soc.–Hum. | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.03 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.39 ** | 0.21 | 0.21 | −0.19 | −0.19 | −0.11 | 0.28 * | 0.23 + | 0.18 |

| BOWIT—Sci.–Tec. | 0.19 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.23 * | 0.12 | 0.15 + | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.44 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.25 * | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.26 * | 0.32 ** | 0.31 * |

| AIST-Realistic | 0.56 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.53 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.45 ** | 0.40 ** | ||||||

| AIST-Investigative | 0.66 *** | 0.53 *** | 0.53 *** | 0.60 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.74 *** | 0.43 ** | 0.50 *** | ||||||

| AIST-Artistic | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.19 * | 0.20 * | 0.06 | −0.06 | 0.01 | ||||||

| AIST-Social | 0.01 | −0.10 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.18 | ||||||

| AIST-Enterprising | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.16 | 0.20 | −19 | ||||||

| AIST-Conventional | 0.17 * | 0.11 | 0.14 * | 0.21 * | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.28 * | ||||||

| ANOVA F, (df) | R2/Radj2 | Predictors | b | Tolerance | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | 24,345 ***, (5) | 0.39/0.38 | AIST—Realistic | 0.33 *** | 0.546 | 1.831 |

| (n = 196) | AIST—Investigative | 0.25 ** | 0.521 | 1.918 | ||

| Big 5—Extraversion | −0.17 ** | 0.925 | 1.081 | |||

| Big 5—Neuroticism | −0.16 * | 0.901 | 1.109 | |||

| BOWIT—Sci.-Tec. | 0.13 * | 0.935 | 1.069 | |||

| Phy.–tec. | 17,318 ***, (5) | 0.33/0.31 | AIST—Realistic | 0.32 *** | 0.492 | 2.031 |

| not favourite | AIST—Investigative | 0.30 ** | 0.449 | 2.226 | ||

| (n = 147) | Big 5—Neuroticism | −0.07 | 0.925 | 1.082 | ||

| BOWIT—Sci.-Tec. | 0.05 | 0.911 | 1.097 | |||

| AIST—Artistic | 0.01 | 0.833 | 1.200 | |||

| Phy.–tec. favourite | 12,080 ***, (2) | 0.35/0.32 | AIST—Realistic | 0.40 ** | 0.951 | 1.051 |

| (n = 49) | BOWIT—Sci.-Tec. | 0.35 ** | 0.952 | 1.051 | ||

| Interest profile SAE | 5655 **, (2) | 0.15/0.13 | Big 5—Extraversion | −0.34 ** | 0.963 | 1.039 |

| (n = 65) | Big 5—Neuroticism | −0.27 * | 0.963 | 1.039 | ||

| Interest profile SI | 4706 *, (2) | 0.13/0.10 | BOWIT—Sci.-Tec. | 0.28 * | 0.946 | 1.057 |

| (n = 67) | Big 5—Neuroticism | −0.17 | 0.946 | 1.057 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pahl, A.; Tschiesner, R. What Influences Attitudes and Confidence in Teaching Physics and Technology Topics? An Investigation in Kindergarten and Primary-School Trainee Teachers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010087

Pahl A, Tschiesner R. What Influences Attitudes and Confidence in Teaching Physics and Technology Topics? An Investigation in Kindergarten and Primary-School Trainee Teachers. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010087

Chicago/Turabian StylePahl, Angelika, and Reinhard Tschiesner. 2022. "What Influences Attitudes and Confidence in Teaching Physics and Technology Topics? An Investigation in Kindergarten and Primary-School Trainee Teachers" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010087

APA StylePahl, A., & Tschiesner, R. (2022). What Influences Attitudes and Confidence in Teaching Physics and Technology Topics? An Investigation in Kindergarten and Primary-School Trainee Teachers. Sustainability, 14(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010087