Abstract

The aim of the paper is to critically evaluate the similarities and differences in the development of the temporal and spatial structure of shopping centers in the Czech and Slovak republics. We focused on the retail transformation and sustainable manifestations of the location and construction of shopping centers. We classified shopping centers according to their genesis, location in the city, and size of the gross leasable area. To analyze migration trends and geographic distribution characteristics of shopping centers in the capital cities of both countries (local level of analysis), we used spatial gravity and standard deviational ellipse. Generally, there is an analogous trend in the development of shopping centers in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, with a particular two- to four-year lag in Slovakia (west–east gradient). Despite this, we still perceive the demand for shopping centers in both countries as above average, and it is not declining. The construction of shopping centers, mainly in small towns, also indicates this trend. In Prague and Bratislava, the pattern of spatial expansion of shopping centers differs. Prague probably represents a more advanced phase of shopping center agglomeration. However, neither country has reached the state of clustering.

1. Introduction

Retail has become an inseparable part of urban residents’ everyday lives. Retail activities and consumers constitute an important element of the spatial organization of urban spaces [1]. Nowadays, it is almost impossible to imagine a city without a shopping zone, usually in the form of a shopping center. The shopping center phenomenon currently belongs to one of the most significant manifestations of urban retail globalization not only in post-socialist Europe, but also in many other countries of the world. The point is not just in the specific appearance of shopping centers, but mainly in the economic, social, and cultural impact they have on the city and society [2]. One of the most fundamental impacts that the existence of shopping centers has is their influence over the change of long-term patterns of shopping behavior and shopping habits with most population groups [3,4,5,6,7].

The term “shopping center” has been developing since the middle of the 20th century and it has often been linked with the USA. A wide range of diverse definitions for shopping center has evolved, frequently reflecting changes within this sector. In a simplified way, a shopping center may be defined as a building containing many outlets yet run as a single piece of real estate. Shopping centers have gradually developed into complex units (in terms of their size, type, function, and so forth), contributing to a fundamental modification of their original concept and identity [8]. A shopping center may be regarded as a certain spatial pattern of homogenous and heterogenous retailers who cluster together in one locality. On the one hand, it is a highly organized retail complex within a building or space composed of several retailers jointly providing customers with complex services. On the other hand, a shopping center is a type of commercial real estate used to integrate operations. Usually, it represents a mix of retail, services, catering, leisure time, amusement, and other combined forms of business [9]. There are diverse opinions regarding the term shopping center and its definitions. In this study, we operate with the definition arising from the International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC, New York, NY, USA), which considers a shopping center to be a collection of retail and other business facilities, which is planned, established, owned, and run as a single unit, typically with its own parking possibilities. The most frequent combination is a shopping gallery, and the primary tenant (magnet) is usually a hypermarket or a supermarket. It is necessary to point out that the minimum gross leasable area of the shopping center is 5000 m2 [10].

Compared to the tradition of shopping centers in developed economies dating back to the 1950s, the shopping center industry has grown rapidly in post-socialist Europe since the 1990s. The first large shopping centers appeared in Central and Eastern Europe in the mid-1990s. Major retail chains put forth their whole strength first in the capitals of Central and Eastern Europe, with an emergence delayed a few years of the shopping centers in the “secondary” cities. The investment decisions were made at the moment when the reversal of the existing commercial sector and purchasing power of populations were attributed to the economic transformation [11] (p. 149). Shopping centers became a symbol of transformation [12,13,14]. While post-socialist countries share many similarities in retail development with other European countries, there are some noticeable differences in spatial distribution or functional structure of shopping centers [15,16,17,18,19].

While many US or Western Europe markets have become saturated [20,21,22], markets in Central and Eastern Europe have not [23,24,25]. Shopping centers in post-socialist countries have become important elements in the urban landscape; however, lack of planning and vision led to chaotic development [2,26,27,28,29] with contrast to other countries (cf. [30,31,32]). There are key factors of the impact of shopping centers on the post-socialist city development, which refer to several elements [11]: (i) Establishing new principles of urban development, market globalisation, and internationalisation; (ii) intensive migrations from city cores into suburban areas; (iii) spatial stratification—place of residence depends on economic standing; (iv) city polycentrism—old urban core and newly formed suburban center created as a consequence of the emergence of shopping centers; (v) shopping centers as a place for socialisation and social activities; (vi) urban policy of new players, which uses plans to illegally facilitate construction of new shopping centers.

The location, size, and tenant mix of shopping centers in Central and Eastern countries do not differ from the Western models described by Guy [33]. The differences are in the rate at which globalization processes manifest themselves and in the adoption of purchasing habits. In the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the process of transition to shopping centers (for example, popularity as a place of shopping) took only a few years, in Western countries it took decades. There is also a difference in ownership. Currently, the majority of shopping centers in post-socialist countries belong to huge foreign commercial chains and relatively few stores belong to domestic owners [34].

Retailing is sometimes seen as the dark side of sustainability, as it promotes consumption on the one hand. However, on the other hand, retailing also has an important role in a sustainable society [35]. Urban sustainability relates to preserving balanced retail systems set into various facilities and shopping environments that can efficiently reflect the needs, wishes and desires of multiple types of consumers. Cities with a robust network of shopping centers that supply goods and services to the nearest area should be more sustainable than those without such a network [36]. Shopping centers can contribute to an effective urban zone’s operation and sustainability [37]. In fact, all sustainability pillars are included. To a great extent, the environmental dimension is related to the idea of purchases being made under one roof and access to services in one place, leading to reduced emissions. Moreover, many countries use retail impact assessment (RIA) tools while constructing new shopping centers, which can be considered sustainable [27].

However, shopping centers play an essential role also in social sustainability. Shopping centers are places where various generations of consumers meet and spend their free time [38,39,40]. Apart from restaurants and cafes, shopping centers include cinemas and various sports facilities. Families and communities spend more and more time there, which may support the sustainability of social capital [37]. Events at shopping centers can realize community functions such as increased social interaction and strengthen social bonds to a certain degree [41]. The economic sustainability of shopping centers is related not only to the economic benefit of the construction and operation of the shopping center itself, but also additional services or poverty reduction [42]. The shopping center is often linked with residential, administrative, or industrial functions in the given locality, which leads to the accumulation of funds at the local level [43,44,45].

This paper aims to assess the development and spatial expansion of shopping centers in the cities, taken as an example of post-socialist countries. The authors intend to identify trends and changes in the sustainable development of shopping centers in both countries by employing comparative and statistical analyses. An important sub-objective is to classify the shopping centers according to selected criteria, considering temporal and spatial aspects on the national level. As for the local level, it is an analysis of the shopping centers’ spatial distribution with selected qualitative elements in Prague and Bratislava, the capital cities, in various periods. The authors try to find out answers to the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the trends in the development of shopping centers on the national level within sustainable development?

RQ2: What are the differences among shopping centers in the Czech Republic and Slovakia according to various classification criteria?

RQ3: What are the trends in the development of shopping centers in a post-socialist city at the local level?

While much academic discussion focuses on the development of shopping centers, little attention is given to their development in post-socialist countries in terms of their sustainability. Is the development unplanned or are there any patterns of spatial organization at the local or national levels? Are such developments linear (or even exponential) or are they based on the life cycle of shopping centers in post-socialist countries as well? Have they already reached their peak or is there space for further development? If so, what development is going on and how will it progress in the future? How are shopping centers changing in these countries, are they copying Western trends or are there specifics that can be identified? At the national level, are shopping centers developing the same way everywhere, or can a certain time lag be discussed in terms of time diffusion trends? This study attempts to fill the research gap on shopping center development in post-socialist countries in relation to their life cycle with respect to their classification and sustainability. The findings can be helpful to shopping center managers and developers in terms of their sustainable development strategy. The study identifies spatial and localization factors that could be emphasized in the future when building sustainable shopping centers.

2. Data and Methods

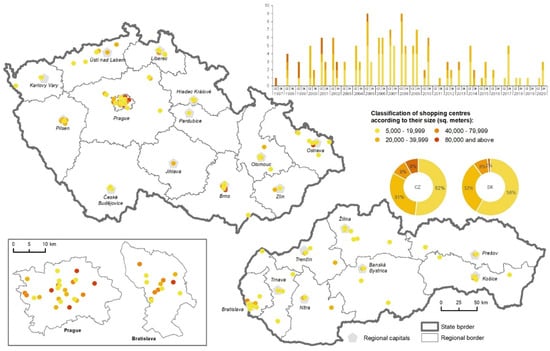

The research includes all shopping centers in the Czech and Slovak republics (Figure 1). The data was obtained from the authors’ internal database. The database comprising all shopping centers in both countries contains information on the opening day, GLA, tenant mix, parking places, and other indicators. The data was gathered continually (a regular survey of annual reports from shopping centers and developers.) and verified in the field research.

Figure 1.

Study area.

On the national level, the first group of methods is based on the description of temporal and spatial aspects of the shopping centers’ development in both countries [6,16,19,46,47]. The second group focuses on the classification of shopping centers in Czech and Slovak cities. The classifications, based on the typical methods of shopping center assessment, are made according to the following criteria: (i) Genesis on brownfields or greenfields, (ii) location in the city, (iii) size of the gross leasable area [6,33,48,49,50].

On the local level (the capitals of both countries), we used methods of spatial gravity and standard deviational ellipse to analyze the migration trends and spatial distribution characteristics of shopping centers [9,51]. As Shi et al. [9] (p. 95) noted, the spatial gravity of shopping centers is an important index for the measurement of shopping center distribution and is represented by points where the spatial forces of all the shopping centers in the region are in balance. We can explain the causes and characteristics of spatial change in shopping centers by studying their spatial gravity’s movement paths and speed. Attributes of the spatial distribution of shopping centers in Prague and Bratislava were calculated using standard deviational ellipse analysis in ArcGIS [52]. Standard deviational ellipse analysis was used to observe spatial directional trends of activities in the study area [53,54]. The ellipse method further advances the concepts of mean center and standard distance by identifying the directional variation of spatial spread captured by the standard distance. In other words, the stores are most spread out along the elongated axis than in other directions [55] (p. 57). A dataset usually describes a geographical phenomenon with certain directional differences. We can see the differences in the directions of expansion of shopping centers for a certain timeframe by comparing the slight differences in the standard deviational ellipses between different points in time [9] (p. 95).

The data was obtained from various sources as there is no integrated institutional source for shopping centers in the Czech Republic or Slovakia. The shopping centers and developers’ web pages were the elementary source from which the information was mainly taken. Professional articles published in topic-focused magazines represented the next source (Retail News, Moderní obchod (Modern Store), Retailmagazin.sk, Tovar a predaj (Goods and Sales), and so forth). The third source of information included statistical sources of national statistic authorities. The authors created this unique database by combining these sources.

3. Retail Transformation and Development of Shopping Centers in the Czech and Slovak Republics

In the middle of 20th century, the urban retail environment of market economies in Europe and Northern America brought new types of stores that could be summarized in several points [30]: (i) The existing establishments’ expansion; (ii) development and improvement of existing and hybrid formats; (iii) emergence of new types of establishments. It was caused by the increased consumption and consumers’ demand. After World War II, retail in post-communist countries, such as the Czech Republic and Slovakia, developed rather in isolation, without any influence of retail globalization trends [56]. The transition from a centrally planned economy to the market economy can be described as a slow process with gradual stabilization of the market.

At the beginning of the 1990s, there was the process of atomization in retail in both countries, which means that a wide range of business structures in this sector emerged and started very actively filling up the niches in the retail network. Retail atomization was characterized by decentralization and de-concentration of the existing structures [57,58]. This phase was followed by the internationalization of retail [59,60,61,62,63]. In this phase, which started in the second half of the 1990s, spatial-organizational concentration was initiated by national retail businesses in the Czech and Slovak markets [59]. The Central European market was hit by the second wave of internationalization when food and non-food foreign retail chains entered the market (for example, Delhaize Le Lion from Belgium, Ahold from Holland, or Billa from Germany). Only this phase of retail development initiated the emergence of shopping centers as a new phenomenon of shopping.

The arrival of foreign chains changed the existing development in retail. The number of stores grew, the business premises got modernized, and new forms of sale, types of retail units, and wholesale warehouses emerged [63]. Foreign companies found the Czech and Slovak markets were attractive, in particular, as a new sales area with a possibility of further expansion of activities beyond the local market [64,65]. The position of foreign companies operating in most post-socialist countries was dominant since the beginning, with little competition from local companies [66]. Domestic businesses suffered from financial and professional disadvantages (small capital, low level of professional management, or lack of experience), preventing them from developing within the large-scale retail sector. Domestic companies had a hard time resisting foreign competition and were forced to withdraw from the market [5,61].

In about half of the first decade of this century, the Czech and Slovak retail gradually developed in a highly competitive sector. Later, not all retail chains remained in it [67]. K-mart (Detroit, MI, USA) left both markets as early as in 1996, and the stores were taken over by Tesco (London, UK). In 2005, the network of Julius Meinl supermarkets was sold to Ahold (Zandan, The Netherlands) in the Czech Republic. One year later, Carrefour (Boulogne, Billancourt, France; the operation was terminated in 2018 in Slovakia) left the Czech market and sold its hypermarkets to its competitor—Tesco, a British retail chain. In 2007, Delvita (Delhaize Le Lion, Anderlecht, Belgium), a discount Belgian retail chain, left the Czech market, and the stores were taken over by Billa (Vienna, Austria); a similar transaction was realized in Slovakia two years earlier. One of the last significant changes in Slovakia was the withdrawal of Ahold (Zandan, The Netherlands). In the Czech Republic, about fifty loss-making stores of Spar (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) were taken over by Ahold in 2014, and Ahold became number one in the Czech Republic. Arrivals and withdrawals of foreign retailers were developing similarly in Slovakia; however, some aspects were different from the Czech Republic, and sometimes also with a different time diffusion.

The experts rank Czech and Slovak retail markets as very competitive and saturated, and therefore it is challenging, even for large international companies, to stay on the market. Thus, the consolidation phase will probably include withdrawals of other large companies from the market in the near future. By gaining their market positions, the concentration tendency in the sector will further strengthen, and other large chains will grow stronger [5,61]. For several years, there have been rumors that Tesco (London, UK) would withdraw from Central Europe; however, such information was recently declared untrue by the company management.

The transformation of the Czech and Slovak retail network was initiated by developing individual large-scale market concepts that represent innovation in the sector and the area [68]. If we leave aside the operational and organizational structures of retail before 1990 represented by regional networks defined at an administrative principle (called “Pramen” and “Jednota”), then the first signs of the emergence of new network structures within Czech and Slovak market retail could be noticed in the first phase of transformation—atomization [59,61,69].

At the beginning of the 1990s, the first foreign companies (for example, Ahold, Delvita) entered the Czech and Slovak retail markets (in a limited scope). They started building their retail network by acquiring the existing stores that met their own company requirements in terms of technology and space. The actual development of new large-scale sale concepts was realized in the second development phase (internationalization) when the largest food and non-food supranational retail groups gradually entered Central Europe [59,61,70].

In connection with the arrival of foreign retail chains on the Czech and Slovak markets, a phase of retail network development realized by building large-size retail units was initiated. Specific networks of large-size operation units were created that gradually started dominating the market [59,62,71]. Similarly, network retail structures were being formed in other Central European countries [25], in Poland [66] or Hungary [23].

A typical feature of the development in the Czech and Slovak markets was a temporal sequence of the development process in individual large-scale market concepts. During such development, the consumer population gradually accepted almost all modern large-scale stores. The development of a retail network was established on the construction of a modern network with a broad spectrum of large-size stores, which can be divided into individual subphases [59,61,70]:

Subphase 1: Dynamic development in supermarkets network (1995 → in the Czech Republic, and 1996 → in Slovakia);

Subphase 2: Dynamic development in discounts network (1997 → in the Czech Republic, and 2004 → in Slovakia);

Subphase 3: Dynamic development in hypermarkets network (1998 → in the Czech Republic, and 1999 → in Slovakia);

Subphase 4: Dynamic development in shopping centers network (2000 → in the Czech Republic and Slovakia).

Globalization trends in retail in both countries belong to the most evident features of social-economic transformation after 1989. This is, among other things, the result of neglecting the space for meeting consumers’ (sale) needs in the period of centrally planned economics compared to market economies [56]. The rapid spread of new and large shopping formats, in the form of shopping centers, in post-socialist Central and Eastern Europe is marked as a “retail revolution” [71]. It is not uncommon in Czech Republic and Slovakia, as in other countries, for shopping centers to be characterized by ‘Gruen effect’ [72], which is based on the disorientation of customers and loss of concentration in the surrounding environment (lighting, stores layout, music). As a result, the customer is distracted (loses track of time and place), which will result in their spending more money, which determines the success of shopping centers. Gruen’s centers were designed to serve the civic, cultural, and social needs of new suburban communities and were intended to be developed alongside apartments, office buildings, theatres, etc. [73].

The development of shopping centers in the Czech Republic and Slovakia needs to be understood in a broader space-related context. Shopping centers are among the preferred shopping options in the whole of Europe. This fact is proved by the density of shopping centers based on the size of their gross leasable area (m2) per 1000 inhabitants of a country (Figure 2), which reaches above-average values in many post-communist countries (Slovenia, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia). Vice-versa, the values in some countries are below the average (Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, and so forth), where a mass development of shopping center construction can be expected in the future [74]. In any case, these are values that should be taken into account for whole countries. The values of large, metropolitan cities and the rest of the country may vary. While the development of shopping centers was delayed in Eastern Europe (mainly after 1995, or as the case may be, after 2000) compared to Western Europe, the current state shows rapid adaptation of consumers to this shopping format, in which case, their development, in terms of the retail life cycle, has not reached the maturity phase, yet.

Figure 2.

The density of shopping centers in selected European countries in 2018. Source: according to [74].

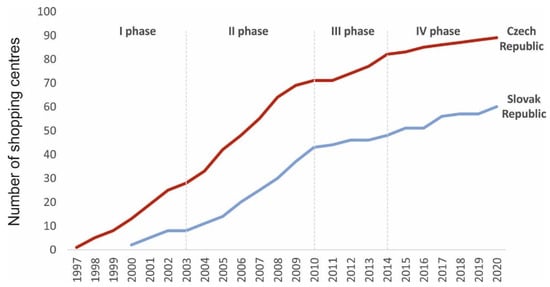

During 30 years of the contemporary development of retail, 89 shopping centers have emerged in the Czech Republic and 60 shopping centers in Slovakia. The development of shopping centers in the Czech Republic and Slovakia may be divided into four phases. The first initial phase relates to the opening of the first shopping centers till 2003. The first shopping center in the Czech Republic was opened in 1997, and three years later in Slovakia (Figure 3). The first phase of shopping center construction developed more intensively in the Czech Republic, where 31.5% of all shopping centers were established by 2003. In Slovakia, the development of shopping center construction was less dynamic; 13.3% of the existing shopping centers were opened by 2003 (comparatively, shopping centers in the Czech Republic began to develop earlier). The initial phase of shopping center development was also the first stage of opening the operation (launch/innovation) in the life cycle of shopping centers [75] in both countries. This phase’s typical features include very few shopping centers operating in the given area, thus low competition. Demand for shopping centers exceeded supply in both countries.

Figure 3.

Development of shopping centers in Czech and Slovak republics (1997–2020).

During the second phase of the shopping center development (2004–2010), it is possible to observe a steep rise followed by a culmination of shopping center emergence and gradual stabilization of their number. During this phase, 48.3% of the current shopping centers emerged in the Czech Republic. Development in Slovakia might be marked as more intensive (Figure 3) since more than half of the current shopping centers (58.3%) were opened. In comparison with the life cycle of the shopping centers, many new shopping centers skipped the stage launch and began the stage of accelerated development [75]. Even despite the growing competition, the visits to the shopping centers increased, and their popularity grew in both countries.

The development of shopping center construction during the third phase in the Czech Republic was different from Slovakia. There was a decline in the construction of new shopping centers in both countries caused by the global economic crises [19], and there were also years when no new shopping centers opened. However, the reduction in the dynamics of the development of shopping centers came 1–2 years later in Slovakia, and the impact was more significant (Figure 3). Many shopping centers in the Czech Republic and Slovakia reached the maturity stage [76]. Shopping centers’ profits were slowing down (were decreasing) and some tenants left for another retail format; 12.4% of all shopping centers were established in the Czech Republic during this phase, and 8.3% of those in Slovakia. The downturn in shopping center construction did not mean that large-size retail stores of another format were not being built. A significant development was noticed, mainly in less populated cities, in various concepts of shopping centers and business promenades, as exemplified by retail park concepts such as Big Box, STOP SHOP, and so forth.

In the last phase of the development, there was a gradual growth of shopping centers in the Czech Republic (about one shopping center per year). Development in Slovakia was less linear than in the Czech Republic. Stagnation was observed in two years (Figure 3); however, there was also a significant growth in the number of shopping centers. During this phase, as many as 20% of Slovak shopping centers were established (in the Czech Republic, it was only 7.9%).

4. Classification of Shopping Centers (Spatio-Temporal Aspects)

There are many suggestions for classifying shopping centers provided by various authors [6,33,47,77]. In our study, we have chosen three elementary classification criteria: (i) According to their genesis in brownfields or greenfields, (ii) according to their localization within a city, and (iii) according to their size.

4.1. According to Their Genesis in Brownfields or Greenfields

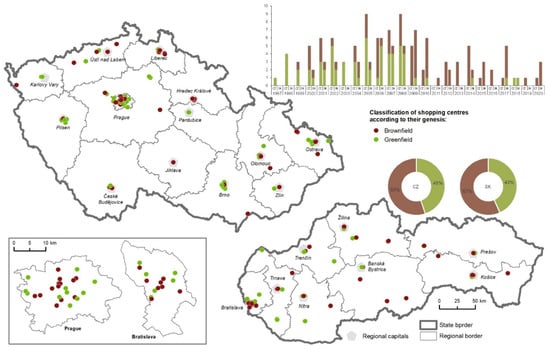

Shopping centers can be distinguished according to their genesis, whether they emerged in greenfields or brownfields (or, in other words, in the previously used land). At first, the development trend of the shopping centers was clearly in favor of greenfields. However, it changed in the last phase when the shopping centers were being constructed in brownfields [6,60]. The current situation in both countries is clearly in favor of the construction of shopping centers in brownfields, which we take as a very city-forming and sustainable way supported by the pressure from the public sector and residents towards developers. Developers themselves also became aware that the purchase power and demand lie in the city, in the center, and therefore they adjusted their investments accordingly (Figure 4). Differences in development in both countries are clearly visible by comparing the time sequences. While the construction of shopping centers in brownfields was prevailing as much as half of the period (since the first shopping center opened) in the Czech Republic (since 2009 very intensively), in Slovakia, it was only the last eight years (one-third of the period). Prevailing construction of the shopping centers in brownfields is typical for all urban categories in both countries (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Classification of shopping centers in the Czech and Slovak republics according to their genesis.

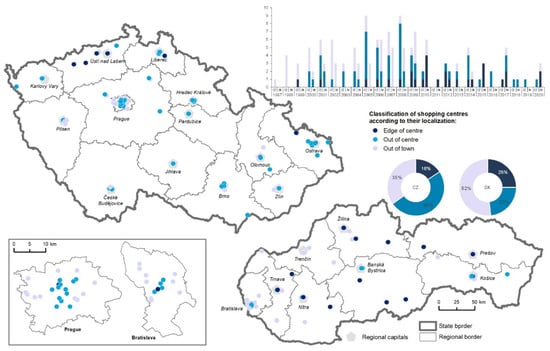

4.2. According to Their Localization

Localization of shopping centers within urban zones can also be regarded as a crucial element of a shopping center’s success [24,26,78]. It is also why the second classification criterion was the localization of shopping centers within basic morphogenetic urban zones [6,19]. The analysis reveals that the localization of the shopping centers is different in both countries, and it has its own specifics. While in the Czech Republic most shopping centers are from the group of “out of center” (49%), in Slovakia the shopping centers are from the group of “out of town” (52%). Moreover, there are the fewest “out of center” shopping centers out of all shopping center categories in Slovakia; in the Czech Republic the shopping centers are often in historic city centers. Localization of shopping centers in historical urban centers is more typical in less populated cities than in capitals (Figure 5). However, both countries have a common trend already lasting the entire decade: The shift of shopping center construction out from peripheral areas (beginning of development) to the city centers (construction in brownfields). Again, it is a trend supporting revival and social-economic sustainability of the city hub and inner-city areas [5,6]. However, the sustainability of a city focused on shopping opportunities cannot be tied only to shopping centers and their expansion. The sustainability of cities highly depends on the city center viability and shopping street resilience [79]. Development of shopping centers in the historic city center or inner city can lead to a conflict between retail zones (shopping streets vs. shopping centers). In post-socialist cities shopping centers predominate over shopping streets [80]. Urban sustainability has been associated with preserving balanced retail systems set in diverse facilities and shopping environments that are able to respond efficiently to the needs, wants, and desires of different types of consumers. Cities with an efficient network of centers that deliver goods and services to the vicinity should be more sustainable than those without such a network [36] (p. 4).

Figure 5.

Classification of shopping centers in the Czech and Slovak republics according to their localization in the city.

4.3. According to Their Size

The last selected classification criterion was the size of gross leasable area (GLA). Shopping centers were classified according to the ICSC methodology (Table 1). A typical feature for both countries is the construction of small shopping centers (more than half of all), and the least counted group includes very large shopping centers (Figure 6). Demand for very large shopping centers is higher in the Czech Republic than in Slovakia. Downsizing of GLA for newly opened shopping centers represents a sustainable trend in both countries. Shopping centers with a GLA of up to 40,000 m2 represent a more than 83% share in the Czech Republic; in Slovakia, it is 88%. An average GLA is relatively stable for Czech shopping centers; it remains at the level of 27,000 m2; it dropped from 22,000 to 20,000 m2 in the following five years in Slovakia [6].

Table 1.

International Standard for European Shopping Center Types.

Figure 6.

Classification of shopping centers in Czech and Slovak republics according to their size.

As already mentioned hereinabove, in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, the current trend and approach towards the localization of shopping centers in Europe are declining from large-size projects that can be found in peripheral urban areas. These localities that already have typical rural features are under pressure concerning the increased intensity of automobile transport and land encroachment, which are mostly perceived as unfavorable, and in terms of socio-economic and environmental aspects, unsustainable, not only by residents but also municipalities and cities’ representatives [5]. Reduction in the construction of large new centers is typical, in particular, for Western Europe. Restrictive policies can be found in Great Britain [81], and in Italy and France [82]. These claims have also been proved by the studies performed by [74], which observe trends in the modernization of the existing centers. Apart from the reasons stated above, the changes in construction are often caused due to the market saturation and changes in shopping preferences.

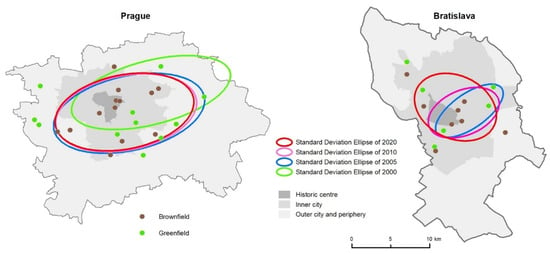

5. Change in the Direction of Spatial Expansion of Shopping Centers in Capitals of the Czech Republic and Slovakia

The analysis of the changes in directions of spatial expansion focuses on the capitals of both countries (Prague and Bratislava). The reason for this is the highest concentration of shopping centers is in these cities. Moreover, the development of shopping centers in Prague and Bratislava has the longest history.

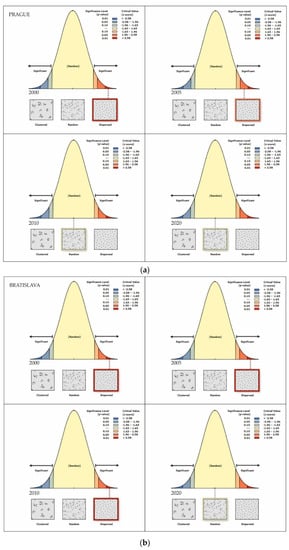

As seen in Figure 7, there are significant differences in the expansion of shopping centers in both cities. Prague is characterized by the initial development of shopping centers located further from the city center towards the east, which might be caused, besides other things, by a denser built-up area in the form of high-rise apartment buildings and housing estates, and thus a higher concentration of population. The given retail structure resulted from the post-socialism expansion of retail with the potential of developer development outside the city centers [12]. After 2000, the gravity center of shopping center development moved towards the city center, while the shopping centers were constructed in suburban zones in the west of the city. Moreover, the ratio of long and short axes of the ellipse decreased, which means that the spatial distribution of shopping centers in Prague is gradually moving towards the initial agglomeration development state (which has not occurred yet). The following phases of the development of shopping centers in Prague are similar in nature. There was no significant spatial expansion outside the city, or the inner city, and the center of gravity of shopping centers only changed slightly.

Figure 7.

Change in standard deviational ellipse and average nearest neighbor of shopping centers in (a) Prague and (b) Bratislava.

In Bratislava, the spatial expansion of shopping centers has different features. The initial phase was not analyzed since, by 2000, only two shopping centers had been established (for the SD ellipse analysis at least three shopping centers are needed). In the phase by 2005, the ellipsis has a north-east gradient, which is in line with urban development trends and sub-urbanization processes [83]. In the next phase (until 2010), the spatial expansion in Bratislava had similar features as in Prague. The spatial expansion lost its momentum and was concentrated more in the inner city up to the historical center [58]. However, the latest development of shopping centers in Bratislava is different from Prague. The emergence of new shopping centers in the western part of the city resulted in the change of spatial expansion of shopping centers in Bratislava (Figure 7).

The degree of spatial agglomeration of shopping centers, measured by the average distance to the nearest neighbor, has a different development in both cities. The analyses reveal that the first two phases of development of shopping centers in Prague are characterized by dispersion distribution of shopping centers in the city. After 2005, it is a random distribution. Bratislava, unlike Prague, reached the random distribution of shopping centers as late as in the last development phase. Neither in Prague nor in Bratislava has there occurred a phase with higher level of agglomeration in the development of spatial distribution of shopping centers that would indicate a clustering distribution pattern (cf. [9]). The nearest neighbor indices, or R values, of Prague’s/Bratislava’s shopping centers are 2.07/204.4 in 2000, 1.29/1.74 in 2005, 1.19/1.45 in 2010, and 1.10/1.16 in 2020, respectively.

6. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

The development of the urban retail environment has temporal-spatial rules that recur in a generalized form in all developed countries, including the Czech and Slovak republics. The very fast concentration of urban retail after 1990 was supported by a dynamic internationalization manifested through the entrance and rapid establishment of supranational chains with large-size concepts (supermarkets and hypermarkets). Just these new formats quickly gained the favor of consumers and became a favorite shopping format for many consumers in both countries [84,85,86]. This trend persists to this day. Shopping centers in both countries represent an independent urban retail development line. It took less than 25 years until shopping centers became a phenomenon in the Czech and Slovak republics, which changed consumers’ shopping behavior and the general economic and social habits through all generations. Dynamics of the market entrance, development, and popularity of shopping centers with all population groups overtook similar development in developed countries by about four decades.

In both countries, shopping centers have grown significantly in the past two decades, but dynamics have varied over time and space. The expansion of shopping centers is fueled both by customer demand as well as by factors on the supply side. The reasons for the expansion of shopping centers in the Czech Republic and Slovakia can be summarized as [7,40,61,62,86,87,88,89,90]: (i) A rising standard of living of the population (mainly the middle class); (ii) a growing level of consumer mobility (possibility to travel for shopping on the outskirts of the city); (iii) shopping centers are now more than just places to purchase; they are also places for entertainment and leisure (the concept of retailtainment); (iv) competition in the shopping center market is still insufficient and the market is still not saturated; (v) neither in the Czech Republic nor in Slovakia is there effective regulation of shopping center development.

In general, we may observe analogic trends in the development of shopping centers in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, with a particular time lag of two to four years in Slovakia. This time shift in the space with the west–east gradient is called a wave diffusion and is evident in the retail in both countries [6,70,85,87]. However, we still perceive the demand for shopping centers in both countries as above average, and there is no decline in it. It is also evident from the plans for shopping center construction, mainly in small towns. On the local level (Prague and Bratislava), we may observe a different development. The spatial expansion of shopping centers has different patterns in various towns regarding spatial orientation and size. Due to the given diffusion in space, Prague is probably characterized by a more advanced phase of shopping center agglomeration. However, the state of clustering has not been reached in either country. It is a random spatial expansion with elements of shopping center agglomeration in the inner city (RQ3).

The trend of shopping center construction in both countries is to decrease the GLA. In terms of sustainability, it can be manifested by taking quality land for the shopping centers at the city’s outskirts, greenfield [91], and at the same time, by the efforts to locate smaller shopping centers in the inner city or its center, and construction based in the so-called brownfield [92]. In both countries, an increased share of construction of shopping centers in brownfields was noticed (RQ2). Taking advantage of such urban brownfields for tourism and leisure time activities could be an excellent possibility for the revival and sustainable development of urban localities [93]. Shopping centers localized in the previously used areas have been built, particularly in city centers and the inner city. Research conducted in Sweden confirmed that consumers’ out-of-town shopping would generate an excess of 60 per cent CO2 emissions, whereas downtown and edge-of-town shopping centers are comparable [94]. Moreover, brownfields can be transformed into greener and sustainable urban places [21] or redeveloped into more sustainable ones [95].

Another sustainable trend, in terms of society and environment (RQ1), is the relocation of the shopping centers’ construction from the outskirts to the inner city or city center [5,6]. This new model appears to be a more effective way to combine the desire for retail investment with the hope of maintaining sustainable cities [96] (p. 174). However, it is necessary to note that the shopping centers located in the historic city center can also have, and they do have, a negative impact on pushing away the tenants from the traditional shopping streets right in the city center. This trend can lead to the fall of neighbor retail regions and the loss of their economic viability [97,98]. In the Czech and Slovak republics, shopping centers have not been closed yet (with one exception in Prague, where the new tenants became furniture companies: XXX Lutz and Möbelix). However, such a negative trend often results from unsustainable decisions made by the shopping center management [99]. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the retail life cycle concept or shopping center life cycle, while evaluating the development of shopping centers as a part of urban retail [75]. Shopping centers in both countries are in the phase of growth, or in some cases, maturity (depending on the type of center); nevertheless, urban retail is undergoing a natural transformation. Therefore, this agenda represents a topic for future research of sustainable social and economic development of shopping centers in post-socialist countries.

There are several limitations in this paper. The first case study examines two countries that previously constituted a single republic. For several decades (before 1993), their economies were determined by uniform policies. Research from other countries (cities) may lead to different results. Another limitation is the analysis at the local level in the case of capitals. Cities with smaller populations may experience different developments. Last but not least, it is important to note the definition of shopping centers, which may vary.

Shopping centers have a significant impact on the transformation of cities in post-socialist countries and have led society towards a kind of homogenization, and the emergence of a consumer society. Both countries’ consumers have started adopting the consumption patterns of other cultures, sometimes without change, sometimes with the addition of local elements. However, society is inherently heterogeneous; not all consumers are unified under the influence of several international corporations. It is questionable what role shopping centers play in this process, which represents opportunities for future shopping center research in the context of sustainability.

Author Contributions

F.K.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation; J.K.: supervision, validation, writing—review and editing; K.B.: formal analysis, data curation, visualization; M.N.: formal analysis, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under Contract No. APVV-20-0302 and grant VEGA 2/0113/19 and by Masaryk University under grant number MUNI/A/1210/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Erkip, F.; Kızılgün, Ö.; Mugan, G. The role of retailing in urban sustainability: The Turkish case. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2013, 20, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slach, O.; Nováček, A.; Bosák, V.; Krtička, L. Mega-retail-led regeneration in the shrinking city: Panacea or placebo? Cities 2020, 104, 102799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D. Shopping Tourism, Retailing and Leisure; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Spilková, J. Geografie Maloobchodu a Spotřeby: Věda o Nakupování; Karolinum: Prague, Czech Republic, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kunc, J.; Maryáš, J.; Tonev, P.; Frantál, B.; Siwek, T.; Halás, M.; Klapka, P.; Szczyrba, Z.; Zuskáčová, V. Časoprostorové Modely Nákupního Chování České Populace; Masarykova univerzita: Brno, Czech Republic, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Križan, F.; Kunc, J.; Bilková, K.; Barlík, P.; Šilhan, Z. Development and Classification of Shopping Centers in Czech and Slovak Republics: A Comparative Analysis. AUC Geogr. 2017, 52, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospěch, P. Urban or family-friendly? The presentation of Czech shopping centers as family-friendly spaces. Space Cult. 2017, 20, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, M.; Musa, Z.N. Towards defining shopping centres and their management systems. J. Retail. Leis. Prop. 2009, 8, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.S.; Wu, J.; Wang, S.Y. Spatio-temporal features and the dynamic mechanism of shopping center expansion in Shanghai. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 65, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J. One Step Closer to a Pan-European Shopping Center Standard. Illustrating the New Framework With Examples. Features Res. Rev. 2006, 13, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Vujisić, K.; Krklješ, M. The impact of shopping centres on the restructuring in the post-socialist cities with a particular focus on Podgorica. Facta Univ. Ser. Archit. Civil. Eng. 2020, 18, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommois, C. The retailing urban structure of Prague from 1990 to 2003: Catching up with the western cities. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2004, 11, 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Spilkova, J. The birth of the Czech mall enthusiast: The transition of shopping habits from utilitarian to leisure shopping. Geografie 2012, 117, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sýkora, L.; Bouzarovski, S. Multiple transformations: Conceptualising the post-communist urban transition. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebernik, D.; Jakovčić, M. Development of retail and shopping centres in Ljubljana. Dela 2006, 26, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovčić, M.; Rebernik, D. Comparative Analysis of Development of Retail and Shopping Centres after 1990 in Ljubljana and Zagreb. Hrvat. Geogr. Glas. 2008, 70, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kunc, J.; Križan, F.; Bilková, K.; Barlík, P.; Maryáš, J. Are there differences in the attractiveness of shopping centres? Experiences from the Czech and Slovak Republics. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2016, 24, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochmińska, A. Shopping centres as the subject of Polish geographical research. Geogr. Pol. 2016, 89, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikos, T.T. Changes in the retail sector in Budapest, 1989–2017. Reg. Stat. 2019, 9, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, J.D. Retail saturation: Inevitable or irrelevant? Urban Geogr. 2000, 21, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, P. Shopping centres in decline: Analysis of demalling in Lisbon. Cities 2019, 87, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burayidi, M.A.; Yoo, S. Shopping Malls: Predicting Who Lives, Who Dies, and Why? J. Real Estate Lit. 2021, 29, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, E. Winners and losers in the transformation of city centre retailing in East Central Europe. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2001, 8, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunc, J.; Tonev, P.; Szczyrba, Z.; Frantál, B. Shopping Centres and Selected Aspects of Shopping Behaviour (Brno, the Czech Republic). Geogr. Tech. 2012, 16, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kunc, J.; Križan, F. Changing European retail landscapes: New trends and challenges. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2018, 26, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, H.J. Restructuring Retail Property Markets in Central Europe: Impacts on urban space. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2007, 22, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilková, J. Retail Development and Impact Assessment in Czech Republic: Which Tools to Use? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 1469–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksić, M. Institutional obstacles in large-scale retail developments in the post-socialist period—A case study of Niš, Serbia. Cities 2016, 55, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthals Altes, W.K. Freedom of establishment versus retail planning: The European case. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, J.R. Retail Impact Assessment: A Guide to Best Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, D. The rise (and fall?) of national retail planning. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2002, 93, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, C. Planning for Retail Development: A Critical View of the British Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, C.M. Classifications of retail stores and shopping centres: Some methodological issues. GeoJournal 1998, 45, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudny, W. Manufaktura in Łódź, Poland: An example of a festival marketplace. Norsk. Geogr. Tidssk. 2016, 70, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, M.; Lundberg, C.; Ziakas, V. Episodic Retail Settings: A Sustainable and Adaptive Strategy for City Centre Stores. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Guimarães, P. Public policy for sustainability and retail resilience in Lisbon City Center. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydin, Y. Planning for Sustainability: Lessons from Studying Neighbourhood Shopping Areas. Plan. Pract. Res. 2019, 34, 522–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilková, J.; Radová, L. The formation of identity in teenage mall microculture: A case study of teenagers in Czech malls. Sociol. Cas. 2011, 47, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Križan, F.; Bilková, K.; Kunc, J.; Sládeková Madajová, M.; Zeman, M.; Kita, P.; Barlík, P. From school benches straight to retirement? Similarities and differences in the shopping behaviour of teenagers and seniors in Bratislava, Slovakia. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2018, 26, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunc, J.; Reichel, V.; Novotná, M. Modelling frequency of visits to the shopping centres as a part of consumer’s preferences: Case study from the Czech Republic. International J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.S.; Lo, S.M. Events as community function of shopping centers: A case study of Hong Kong. Cities 2018, 72, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduful, A.K. Economic impacts of shopping malls: The Accra (Ghana) case study. Cities 2021, 103371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, C.; Schnedlitz, P. Drivers of agglomeration effects in retailing: The shopping mall tenant’s perspective. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 1043–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanen, H.; Kohijoki, A.-M.; Saastamoinen, K. Profiling the ageing wellness consumers in the retailing context. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2016, 26, 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, J.; Maggioni, I.; Sands, S. Critical success factors of temporary retail activations: A multi-actor perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 40, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek-Mańkowska, S.; Križan, F. Shopping centres in Warsaw and Bratislava: A comparative analysis. Misc. Geogr. 2010, 14, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkip, F.; Ozuduru, B.H. Retail development in Turkey: An account after two decades of shopping malls in the urban scene. Prog. Plan. 2015, 102, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrudan, I.N. Definitions and classifications of shopping centers. Mark. Inf. Decis. 2011, 4, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, P. Shopping Environments; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dolega, L.; Reynolds, J.; Singleton, A.; Pavlis, M. Beyond retail: New ways of classifying UK shopping and consumption spaces. Environ. Plan. B 2021, 48, 132–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rišová, K.; Madajová Sládeková, M. Gender differences in a walking environment safety perception: A case study in a small town of Banská Bystrica (Slovakia). J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 85, 102723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rišová, K. Questioning gender stereotypes: A case study of adolescents walking activity space in a small Central European city. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 91, 102970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, A.A. Creating a GIS Application for Retail Facilities Planning in Jeddah City. J. Comput. Sci. 2011, 7, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rizwan, M.; Wan, W.; Gwiazdzinski, L. Visualization, spatiotemporal patterns, and directional analysis of urban activities using geolocation data extracted from LBSN. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, C.; Xiu, C.; Zhang, P. Location analysis of retail stores in Changchun, China: A street centrality perspective. Cities 2014, 41, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krásny, T. Retailing in Czechoslovakia. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 1992, 20, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczyrba, Z. Geografie Obchodu se Zaměřením na Současné Trendy v Maloobchodě; Univerzita Palackého: Olomouc, Czech Republic, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Križan, F.; Bílková, K.; Barlík, P.; Kita, P.; Šveda, M. Old and New Retail Environment in a Post-Communist City: Case Study from the Old Town in Bratislava, Slovakia. Ekon. Cas. 2019, 67, 879–898. [Google Scholar]

- Szczyrba, Z. Maloobchod v ČR Po Roce 1989—Vývoj a Trendy se Zaměřením na Geografickou Organizaci; Univerzita Palackého: Olomouc, Czech Republic, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Spilková, J. Changing face of the Czech retailing in post-communist transformation: Risks of extreme polarisation under globalisation pressures. In Evolution of Geographical Systems and Risk Processes in the Global Context; Dostál, P., Ed.; Charles University, P3K: Prague, Czech Republic, 2008; pp. 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Križan, F.; Bilková, K.; Kita, P.; Siviček, T. Transformation of retailing in post-communist Slovakia in the context of globalization. E M Ekon. Manag. 2016, 19, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembošová, M.; Dubcová, A.; Nagyová, Ľ.; Cagáňová, D. Development of retail network on the example of three regional towns comparison in West Slovakia. Wirel. Netw. 2020, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitríková, J.; Marchevská, M.; Kozárová, I. Retail. Transformation and Changes in Consumer Behaviour in Slovakia since 1989; VUZF Publishing House “St. Grigorii Bogoslov”: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Drtina, T. The Internationalisation of Retailing in the Czechand Slovak Republics. Serv. Ind. J. 1995, 15, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simová, J. Internationalization in the process of the Czech retail development. E M Ekon. Manag. 2010, 13, 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wilk, W. Western European retail chains in the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia–similarities and differences. Misc. Geogr. 2006, 12, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S.; Davies, K.; Dawson, J.; Sparks, L. Categorizing patterns and processes in retail grocery internationalisation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2008, 15, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pražská, L.; Jindra, J. Retail. Management; Management Press: Prague, Czech Republic, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Starzyczná, H.; Steiner, J. Maloobchod v Českých Zemích v Proměnách let 1918–2000; Slezská Univerzita v Opavě: Karviná, Czech Republic, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Szczyrba, Z.; Kunc, J.; Klapka, P.; Tonev, P. Difúzní procesy v prostředí českého maloobchodu. Reg. Studia 2007, 1, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Garb, Y.; Dybicz, T. The retail revolution in post-socialist Central Europe and its lessons. In The Urban Mosaic of Post-Socialist Europe; Tsenkova, S., Nedović-Budić, Z., Eds.; Physica-Verlag Heidelberg: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, M.J. Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, M.S. Britain’s regional shopping centres: New urban forms? Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman & Wakefield. European Shopping Centre Development Report. 2017. Available online: http://www.cushmanwakefield.cz/en-gb/research-andinsight/2016/european-shopping-centre-development-report-november-2016 (accessed on 9 July 2021).

- Lowry, J.R. The life cycle of shopping centers. Bus. Horiz. 1997, 40, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, P.; Kita, J.; Križan, F.; Bilková, K.; Kunc, J. Marketing Spotreby; Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sikos, T.T.; Hoffmann, M. Typology of Shopping Centres in Budapest; J. Selye University Research Institute: Komárno, Slovakia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sikos, T. Key to the success of the outlet shopping centers located in optimal site. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2009, 58, 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ozuduru, B.H.; Varol, C.; Ercoskun, O.Y. Do shopping centers abate the resilience of shopping streets? The co-existence of both shopping venues in Ankara, Turkey. Cities 2014, 36, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, C.; Wood, S.; Floh, A. Adaptive resilience and the competition between retail and service agglomeration formats: An international perspective. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 1537–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, C.M. Controlling new retail spaces: The Impress of Planning Policies in Western Europe. Urban Stud. 1998, 35, 953–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, L. Retail Planning Policy in Italy. In Retail Planning Policies in Western Europe; Davies, R.L., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1995; pp. 144–159. [Google Scholar]

- Šveda, M.; Madajová, M.; Podolák, P. Behind the differentiation of suburban development in the hinterland of Bratislava, Slovakia. Sociol. Cas. 2016, 52, 893–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Večerník, J. Household Consumption in there Czech Republic: From Shopping Queues to Consumer Society. Pol. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 162, 153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kunc, J.; Tonev, P.; Szczyrba, Z.; Greplová, Z. Perspektivy nákupních center v České republice s důrazem na lokalizaci v urbánním prostředí. Urban Územní Rozv. 2012, 15, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Búzik, B.; Zeman, M. Hodnoty v regulácii spotrebiteľského správania. Sociológia 2020, 52, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczyrba, Z. Development of retail geographical structure in the Czech Republic: A contribution to the study of urban environment changes. Acta Univ. Palacki. Olomuc.-Geogr. 2010, 41, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Trembošová, M.; Dubcová, A.; Štubňová, M. The specifics of retail networks spatial structure in the city of Žilina. Geogr. Cassoviensis 2019, 13, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitríková, J.; Marchevská, M.; Kozárová, I.; Bezpartochnyi, M.; Britchenko, I.; Vazov, R. Current Shopping Trends in Slovakia. Young Sci. 2021, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembošová, M.; Dubcová, A.; Nagyová, Ľ.; Cagáňová, D. The Specifics of the Retail Network and Consumer Shopping Behaviour in Selected Regional Towns of West Slovakia. In Advances in Industrial Internet of Things, Engineering and Management; Cagáňová, D., Horňáková, N., Pusca, A., Cunha, P.F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 39–74. [Google Scholar]

- Spilková, J.; Šefrna, L. Uncoordinated new retail development and its impact on land use and soils: A pilot study on the urban fringe of Prague, Czech Republic. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantál, B.; Kunc, J.; Nováková, E.; Klusáček, P.; Martinát, S.; Osman, R. Location matters! Exploring brownfields regeneration in a spatial context (A case study of the South Moravian Region, Czech Republic). Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2013, 21, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navratil, J.; Krejci, T.; Martinat, S.; Pasqualetti, M.J.; Klusacek, P.; Frantal, B.; Tochackova, K. Brownfields do not “only live twice”: The possibilities for heritage preservation and the enlargement of leisure time activities in Brno, the Czech Republic. Cities 2018, 74, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carling, K.; Håkansson, J.; Jia, T. Out-of-town shopping and its induced CO2-emissions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunham-Jones, E.; Williamson, J. Dead and Dying Shopping Malls, Re-Inhabited. Archit. Des. 2017, 87, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newmark, G.L.; Plaut, P.O.; Garb, Y. Shopping travel behaviors in an era of rapid economic transition: Evidence from newly built malls in Prague, Czech Republic. Transport. Res. Rec. 2004, 1898, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.; Paiva, D. The death and life of shopping malls: An empirical investigation on the dead malls in Greater Lisbon. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2017, 27, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, P. The evolution of old shopping centres in the town centre of Braga, Portugal. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2018, 10, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, P. The resilience of shopping centres: An analysis of retail resilience strategies in Lisbon, Portugal. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2018, 26, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).