1. Introduction and Study Context

Perhaps the most significant question from the supply side of tourism and on the part of local destination societies is whether incoming tourism growth may foster both further development of the local/regional/national tourism industry and, more importantly, overall development at the local level and beyond. This question, purposefully or inadvertently, implicates issues of sustainability. As such, this question has been extensively addressed by tourism and development researchers for decades, since the end of the 1980s, while more recent research efforts aim at refining and/or expanding relevant theory and epistemology [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

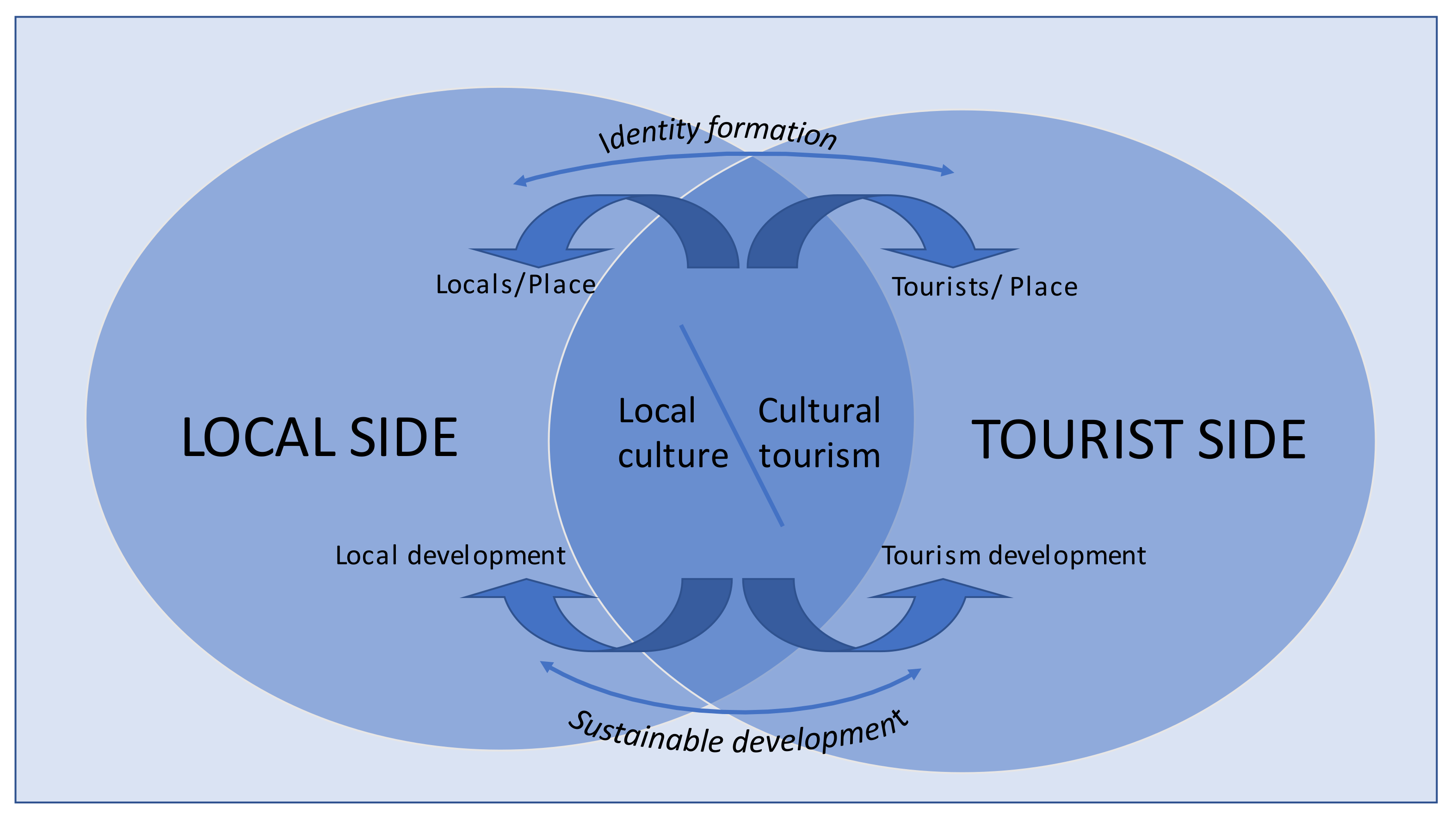

The multifold and contested relationship of tourism to development has been approached from various standpoints, on the basis of the threefold scheme of economy–society–environment, which has recently been enriched and enhanced with the cultural dimension [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The cultural dimension of sustainability issues, resource uses, practices, demands and interests, etc., including tourism prospects and repercussions, adds a further level of analysis and operationalization to the three pillars of ‘sustainability’, the bases on which tourism values, processes and choices may be negotiated and effectuated. Furthermore, culture itself represents the most basic and integrative societal parameter at any destination, encapsulating all manner of human life and thought and its derivative products, practices, meanings, symbols, representations, etc. Cultural tourism addresses all of the latter as points, areas, discourses and experiences of tourist attraction, rendering them tourism products [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The significance of culture for tourism and concern about the cultural impacts of tourism have been explicitly expressed by various sides [

17]. Furthermore, in the current turbulent and transitional times for tourism, issues of sustainability, growing environmental awareness and cultural sensitivity, realizations by destination regions of the precious resources they possess and their vulnerability [

18], as well as changing market demands, become especially poignant, pressing and pivotal for tourism and destinations in general, calling for renewed scientific investigation and deciphering of trends, attitudes, needs, challenges and prospects. Indicatively, “climate change is calling for a transformational and regenerative approach to cultural tourism where the priorities focus on building resilient and adaptive communities and heritage places” [

17] (p. 8).

In this context, this paper explores the cultural tourism perceptions, practices, concerns and prospects held among local residents, tourists and business representatives in the case of the Cycladic Islands, specifically three sites (Andros, Syros and Santorini), aiming to analyze the variable interrelationships between culture and tourism in the development primarily of cultural tourism and secondarily in overall local sustainability. The archipelago of the Cyclades was selected as our case study since it is one of the most significant tourism destinations in Greece while it also features a rich current and past cultural heritage.

The theoretical framework partly relies on the seminal work by Soini and Birkeland [

10] on cultural sustainability, and the methodological approach was an on-site intensive questionnaire survey, effectuated in the context of the SPOT Horizon 2020 EU project, on cultural tourism in the Cyclades, based on the principles of overall sustainability and Europeanization. The concept and framework of cultural sustainability is employed to discuss and contextualize our findings on the variable interrelationships between culture and tourism in these islands, with an emphasis on the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats in the development of cultural tourism and its contribution to local sustainability, from a bottom-up destination perspective.

3. Research Design and Methodology

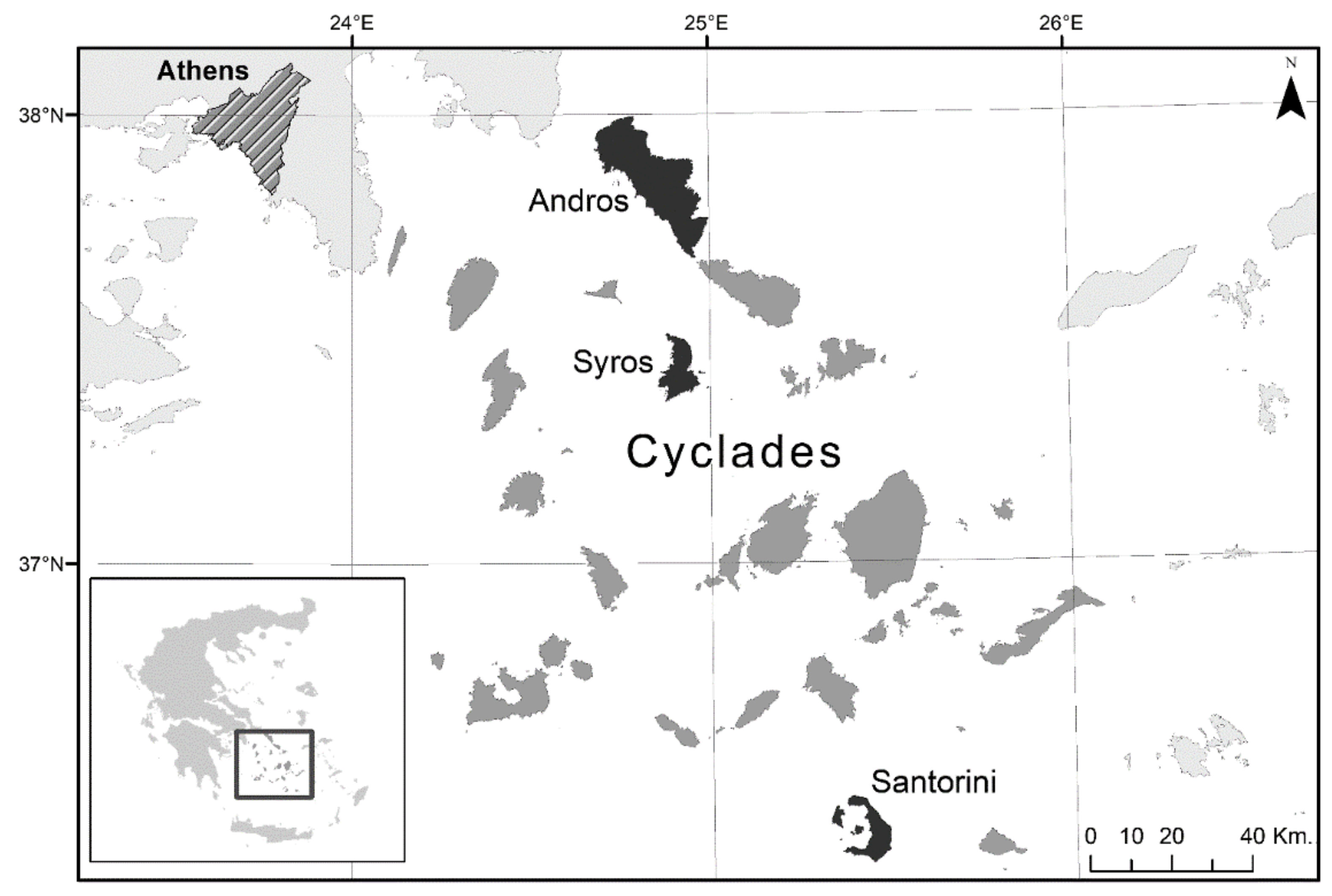

First and foremost, the objective of this paper was to explore cultural tourism perceptions, practices, concerns and prospects among local residents, tourists and business representatives, in the case of the Cycladic Islands (

Figure 2), in order to analyze the variable interrelationships between culture and tourism in the development of cultural tourism. Secondarily, this paper aimed to discuss these interrelationships in the context and towards the prospect of overall local sustainability. The Cyclades, especially the islands of Mykonos and Santorini, are among the most world-renowned global tourism destinations in Greece [

36,

50,

52]. They are highly competitive with other top global destinations, while offering “a truly exotic experience at a price better or equal to a holiday in Europe” [

53]. Besides their strong 3Ss (sea–sand–sun) allure, they also boast striking natural/environmental assets, great landscape diversity and rich cultural traditions and heritage, dating back to antiquity [

53,

54]. Indicatively, foreign tourist hotel stays in the Cycladic islands have been gradually growing, reaching more than 768,000 arrivals in 2018 [

55]. The Cyclades have been selected as our case study area on the basis of their striking presence in the global tourism industry as 3Ss (sea–sand–sun) destinations, but also for their distinctive cultural competitive edge, which has not yet been developed to its full potential. At the same time, these islands are extremely dependent on tourism, thus representing a good case study for issues of overall, as well as cultural, local sustainability.

The concept and framework of ‘cultural sustainability’ was employed to analyze our findings on the variable interrelationships between culture and tourism, with an emphasis on the role of these interrelationships in the development of cultural tourism and overall local sustainability, from a bottom-up perspective. For the purposes of our study, three extensive and in-depth questionnaires (one for local residents, one for tourists and one for business representatives) were constructed in order to address the main research questions, which were as follows:

Research Question 1 (RQ1). What role does culture play in tourism in the Cyclades, and vice versa?

Research Question 2 (RQ2). What are the implications of cultural tourism for local (cultural) sustainability?

The research questions were addressed through the respondents’ personal perceptions, opinions, experiences, etc. regarding these issues. Specifically, the questionnaires were organized for the field survey in the context of the SPOT Horizon 2020 EU project, focusing more generally on cultural tourism and Europeanization, aiming towards sustainable development benefitting host communities and regional economies (SPOT Proposal Part A, p. 3,

http://www.spotprojecth2020.eu, accessed on 18 July 2021). Informed consent was obtained for such work with the human subjects of our study according to EU ethics requirements, in the context of the SPOT project, from the Mendel University Committee of Ethics (coordinating institution of SPOT). The survey was conducted by the authors through on-site visits to the islands of Andros, Syros and Santorini, which were the three sites of our case study (the Cycladic Islands, Greece) during the period of July 2020 to September 2020.

Fieldwork, enriched by the researchers’ own participant observation, was conducted in three locations on Andros Island, between 25 July 2020 and 31 July 2020. The locations were selected as characteristic of the range of different conditions pertaining to tourism and culture on the island. This approach, based on the axes of tourism and urbanity, was decided upon in order to ensure a certain degree of representativeness vis-à-vis these conditions in each case; the same approach was subsequently followed for the other two islands. More specifically, we surveyed locations of both high and low tourist concentration/development, which included both urban and rural/small town locations, since urbanity also correlates with cultural heritage, cultural activities and certainly cultural tourism. For the island of Andros, these locations were: (a) the heavily touristic town of Batsi, (b) the capital of the island, Chora, and (c) the less touristic fishing village of Korthi. Altogether, 49 resident responses, 40 tourist responses and 47 business representatives’ responses were collected in Andros. The second part of the survey took place on the island of Syros between 30 August 2020 and 6 September 2020 and, following the same approach as before, residents were surveyed in (a) the highly touristic seaside resort of Galissas, (b) the capital city of Hermoupolis and (c) smaller inland towns/villages. In total, 44 resident responses, 13 tourist responses and 9 business representatives’ responses were obtained in Syros. The third part of the survey was conducted on the island of Santorini (Thira), between 17 September 2020 and 25 September 2020, specifically in (a) the heavily touristic town of Oia, (b) the capital of the island, Fira (Thera), and (c) the less touristic and more residential town of Emporio. In total, 40 resident responses, 18 tourist responses and 30 business representatives’ responses were collected there.

Our survey respondents were approached in person in central squares, local shops, hotel lobbies and grounds, cafes, bus/port stations, playgrounds and seaside promenades. Questionnaires were administered in written and/or electronic form, using Google Forms, whereas some respondents preferred on-the-spot completion in the form of an interview while the researcher read and filled out the questionnaire for them. We also employed intensive follow-up and email reminders to urge or remind our study participants to deliver the questionnaires. It must be noted that, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a considerable number of residents avoided contact with our research team members or refused to fill out printed questionnaires in order to avoid human contact and the exchange of materials (i.e., pens, printed questionnaires, etc.). Finally, the survey findings were organized, analyzed and manipulated with the aid of the descriptive statistics tool (Microsoft Excel Version 16.0, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Due to the small sample size of our survey participants, it was not possible to conduct correlational statistical analysis.

4. Results

In this section of the article, after a brief description of our interviewees’ profiles (

Table 1 and

Table 2) and the character of local tourism in the Cyclades, we present the output of our survey in the three Cycladic Island destinations, ordered by research question, under which we encompass all the pertinent questions addressed to each of the three groups: residents, tourists and business representatives. These constitute 10 closed-ended questions and 2 open-ended ones, the following: (1) “How does the area profit from cultural tourism?” (open-ended question addressed to the residents) and (2) “Are there, according to your opinion, any tourist facilities missing, which would improve the area as a tourist destination?” (open-ended question addressed to the tourists). We proceed to present the survey findings for each research question as conducted with the aid of descriptive statistical tests.

Due to their close proximity to and easy accessibility from the large urban metropolis of Athens, the Cyclades tend to attract a very high share of domestic tourism [

54,

56]. The majority of our respondents accordingly replied that the majority of visitors on the three islands were domestic tourists, while the second most important visitor group were international tourists arriving from the EU, followed by international tourists arriving from outside the EU. Andros and Syros tend to attract a great number of domestic tourists, followed by EU tourists. It is only the island of Santorini that seems to attract the majority of international tourists outside the EU.

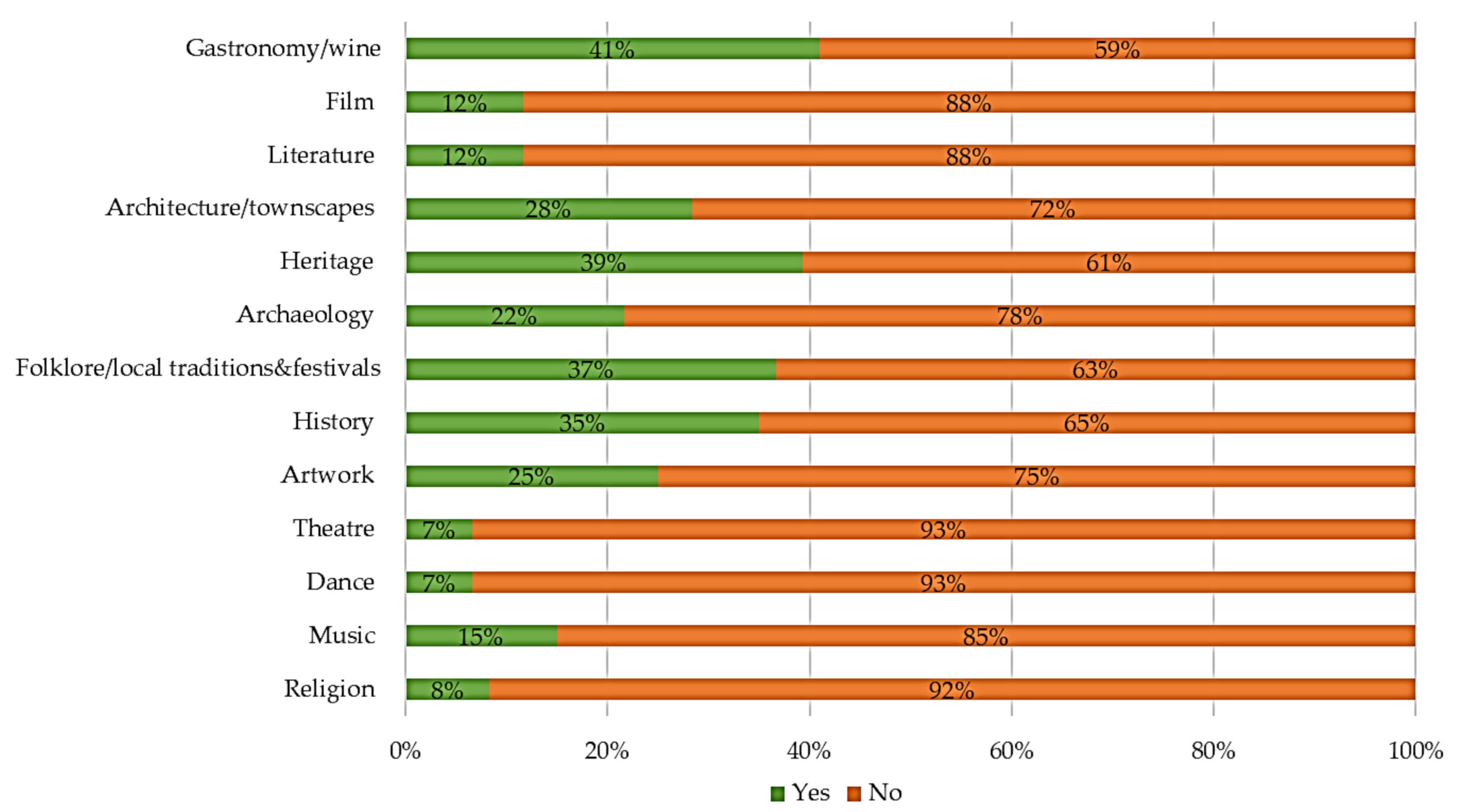

In regard to our businesses’ sample profile, the majority of businesses (85%) for all three islands were located within a radius of less than 2km of the main local cultural sites and attractions. About half (48%) of the businesses that participated in the questionnaire survey, on all three islands, were hotels and tourism resorts, followed by leisure centers and visitor-attraction types of business (27%), catering (9%) and ‘other’ types of business (16%) including tourist shops, travel agencies, museums/art galleries, etc. The majority of tourists attracted by these businesses were couples or lone travelers, and secondarily families. Special-interest tourism, the broadest and most inclusive tourism type/category, emerged as the third most important type of tourism for the surveyed businesses. Special-interest tourism in Andros referred mostly to hiking tourism, outdoor activities and the arts; in Santorini it referred to a broad variety of activities, with an emphasis on gastronomy/wine tourism; and in Syros it referred mostly to arts festivals attendance. As for the cultural services offered by the businesses in our sample, 41% of them provided gastronomy/wine, 39% offered heritage products/services, 37% provided folklore/local traditions, and the rest provided services, experiences, goods etc. in the sectors of history, architecture and art (

Figure 3). A total of 83% of businesses that charged an admission fee answered that the fee was less than 25 Euros, followed by 17% of them who stated that they charged a fee of 25–50 euros.

Generally speaking, the Cycladic islands feature small- and medium-scale tourism, as opposed to ‘industrial tourism’, meaning that they are not as heavily reliant on mass/package tourism (with the exception, perhaps, of Mykonos and Santorini), a trend also reflected in the locally supplied types of accommodation [

57,

58,

59]. The latter include family operations to a very high degree—some of which may also not be institutionalized. These trends are especially evident in our business sample profile, where 55% of businesses were reportedly family owned, which is very typical for the tourism industry in the Cyclades, but especially for the islands of Andros and Syros. When destinations, such as Santorini, gain more international popularity and tourism investments, they also tend to attract more privately-owned businesses (39% of our business sample) or to become part of an international hotel chain (3% of our business sample). The growth and development of all other sectors of local development in the Cyclades (such as primary-sector activities, services, culture, gastronomy, etc.) tend to follow that of tourism, which is the main source of income for the whole region.

Research Question 1 (RQ1). What role does culture play in tourism in the Cyclades, and vice versa?

4.1. Tourist Motivations to Visit the Area

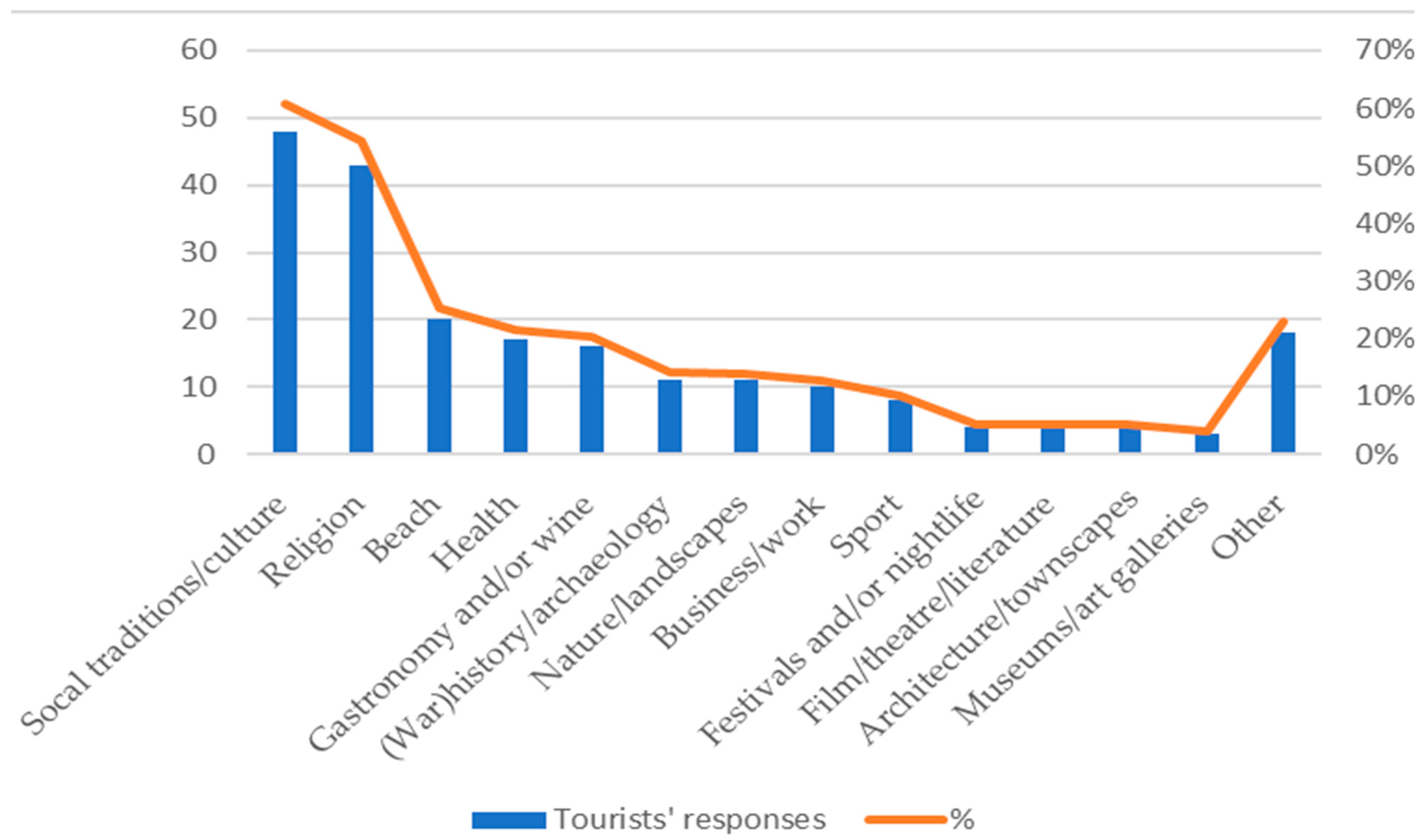

A number of questionnaire questions to the three categories of our respondents addressed the first one of our two research questions. In this first question, addressed to the tourists, the majority of our respondents (61%) replied that local traditions and culture were the main motive to visit the islands of our case study, closely followed by religious (54%) motives (

Figure 4). These results were largely expected, due to the high percentage of domestic tourists visiting these destinations. The next highest category of tourists, at quite a distance from the previous one, (25%), replied that going to the beach was also very important. It can also be inferred from the results of this question that going to the beach and generally relaxing during holidays offers health and wellbeing benefits, a possible explanation for why health also scored quite highly (22%) as a travel motive. Gastronomy and wine were also high (20%) on the list, as these islands also tend to be very popular for the quality of the local food and wine, in combination with other attractions and activities.

4.2. Tourist Interest in Visiting Cultural Tourism Attractions, Events, Sites, etc.

Overall, interest among the tourists who participated in our study in visiting cultural tourism attractions, events and sites, seemed to be high or very high for all categories of the variable (

Figure 5). More specifically, the vast majority of respondents, both foreign and Greek, responded that they were “Very interested” (52%) or “Interested” (26%) in restaurants and food festivals or gastronomy. Large numbers of tourists also said that they were very “Very interested” (47%) or “Interested” (26%) in local traditions and folklore, followed by those who declared that they were “Very interested” (41%) or “Interested” (28%) in the townscapes of their visited destinations in the three islands of our case study. Very few interviewed tourists seemed not to be interested in any of the aspects and attractions of cultural tourism offered by the three islands. This is also very much in agreement with general statistical trends and facts concerning Andros and Syros, and even more so Santorini, as highly popular Greek (island) tourist destinations [

11].

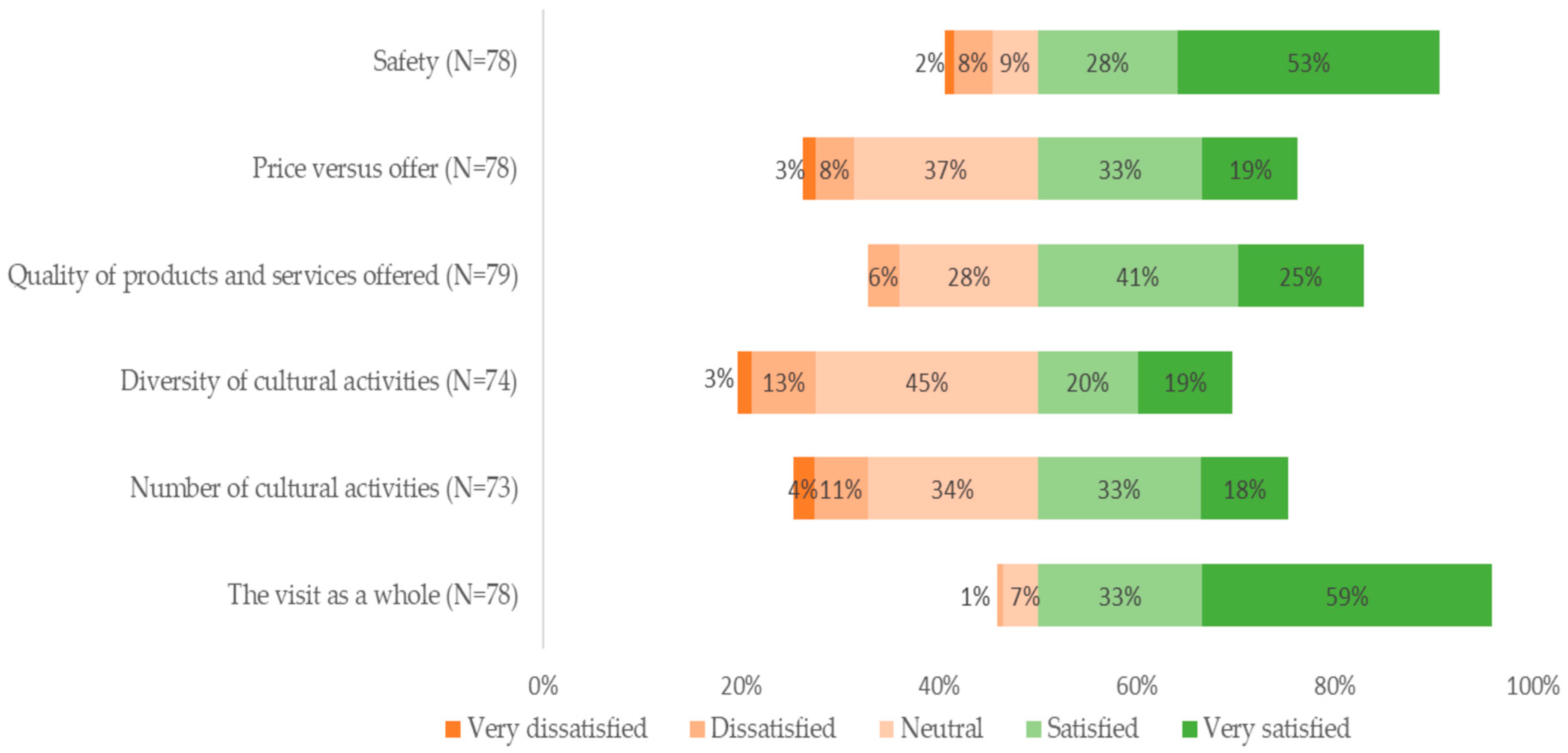

4.3. Tourists’ Satisfaction with Cultural Tourism Aspects

Regarding satisfaction levels with the cultural tourism aspects and attractions of the visited islands of our case study (Andros, Santorini and Syros), the vast majority of the respondents declared that they were “Very satisfied” (59%) or “Satisfied” (33%) with the visit as a whole, thus leaving a margin for improvement (

Figure 6). Large numbers of the tourists participating in our field survey also declared that they were very “Very satisfied” (53%) or “Satisfied” (28%) with the provided safety conditions, followed by those who said that they were “Very satisfied” (25%) or “Satisfied” (41%) with the quality of tourist products and services offered at the destinations, indicating a certain degree of dissatisfaction and consequently implying space for improvement. However, a large number of tourists seemed to be neutral (45%) vis-à-vis the diversity of cultural activities, neutral (37%) as regards the price-versus-offer parameter and also neutral (34%) regarding the number of cultural activities provided in the area of our case study. Very few tourist answers indicated dissatisfaction with the locally provided cultural tourism aspects and attractions.

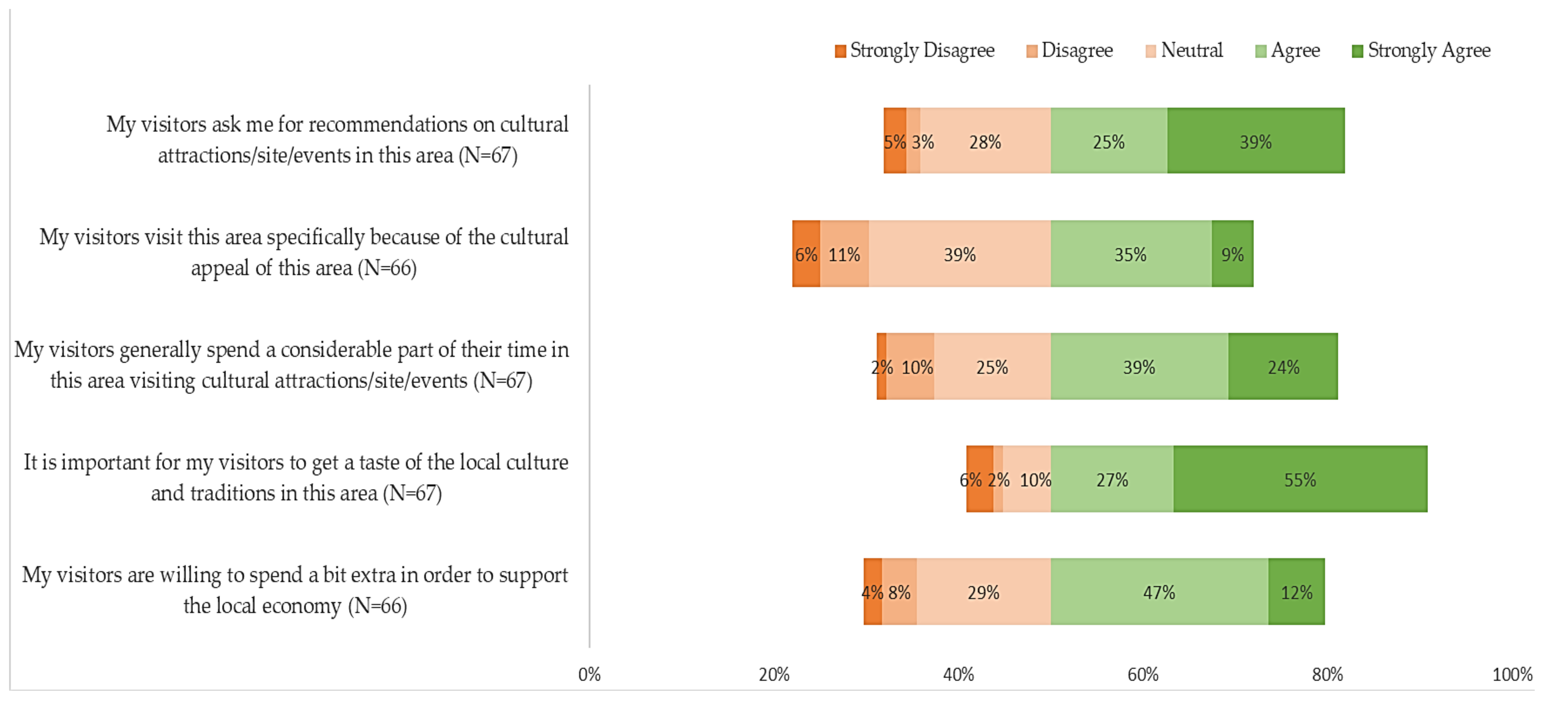

4.4. Businesses’ Perceptions on Cultural Tourism

The cultural appeal of our three islands as tourism destinations seemed to run high according to the responses of business representatives participating in the field survey. Specifically, 55% of them seemed to agree strongly and an additional 24% of them seemed to agree that “It is important for my visitors to get a taste of the local culture and traditions in this area”, despite the fact that cultural tourism is not the primary motive for tourist visits to these islands (

Figure 7). The visitors’ interest in cultural attractions was reported by 25% of the business representatives to be strong and by 39% to be very strong, in that “My visitors ask me for recommendations on cultural attractions/site/events in this area”. Furthermore, 24% of our respondents declared that they strongly agreed and an additional 39% said that they agreed with the statement that “My visitors generally spend a considerable part of their time in this area visiting cultural attractions/site/events.”

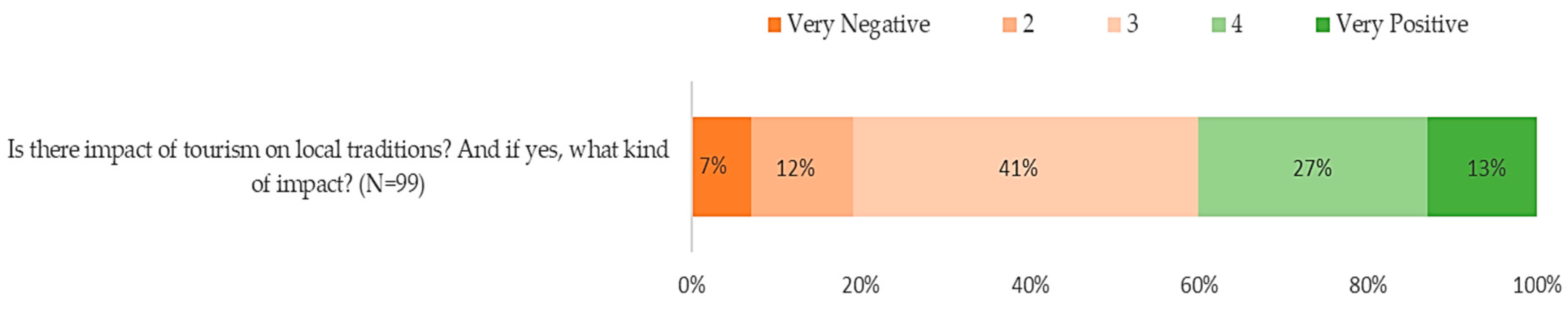

4.5. The Impact of Tourism on Local Traditions According to Residents

Conversely, as expected, the vast majority of our case study resident respondents (73%) stated that tourism also has an impact on local traditions (

Figure 8). Most of the respondents rated this impact as neutral (41%), 12% rated it as negative and 7% as very negative, while 27% rated it as positive and 13% as very positive. Thus, overall, the impact of tourism on local traditions was considered to be positive, with lots of space for improvement.

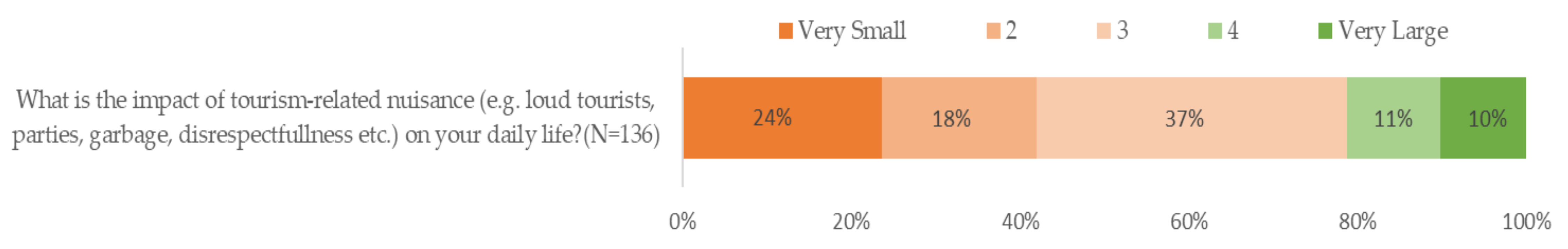

4.6. Impact of Tourism-Related Nuisance on Daily Life According to Residents

Likewise, our findings show that the majority of resident respondents (37%) declared themselves to be neutral as concerns tourism-related nuisance (e.g., loud tourists, parties, garbage, disrespectfulness, etc.) in their island communities, followed by 24% of our respondent sample who claimed that this nuisance was very small, while 18% of them claimed that such nuisance was just small (

Figure 9). Therefore, in the residents’ opinion, tourism did not seem to present a serious problem to the locals’ everyday life.

Research Question 2 (RQ2). What are the implications of cultural tourism for local (cultural) sustainability?

4.7. Residents’ Perceptions on Increased Cultural Tourism Impacts in the Area

All the remaining questions of our study pertain to issues of cultural and overall local sustainability, in connection with tourism and, more specifically, with cultural tourism. These questions refer only to local residents and businesses. With regard to this particular question, 57% of resident respondents seemed to believe that cultural tourism can have a very positive impact on their islands (e.g., infrastructure, jobs, quality of life), in that it may improve both economic and socio-cultural aspects of their lives (

Figure 10). A total of 26% also rated cultural tourism as quite positive for their area and local community, indicating a very strong apparent leaning of the resident interviewees towards the overall very positive impacts of cultural tourism on various aspects of their lives.

4.8. Residents’ Perceptions on Cultural Attractions/Sites/Events’ Importance in the Area

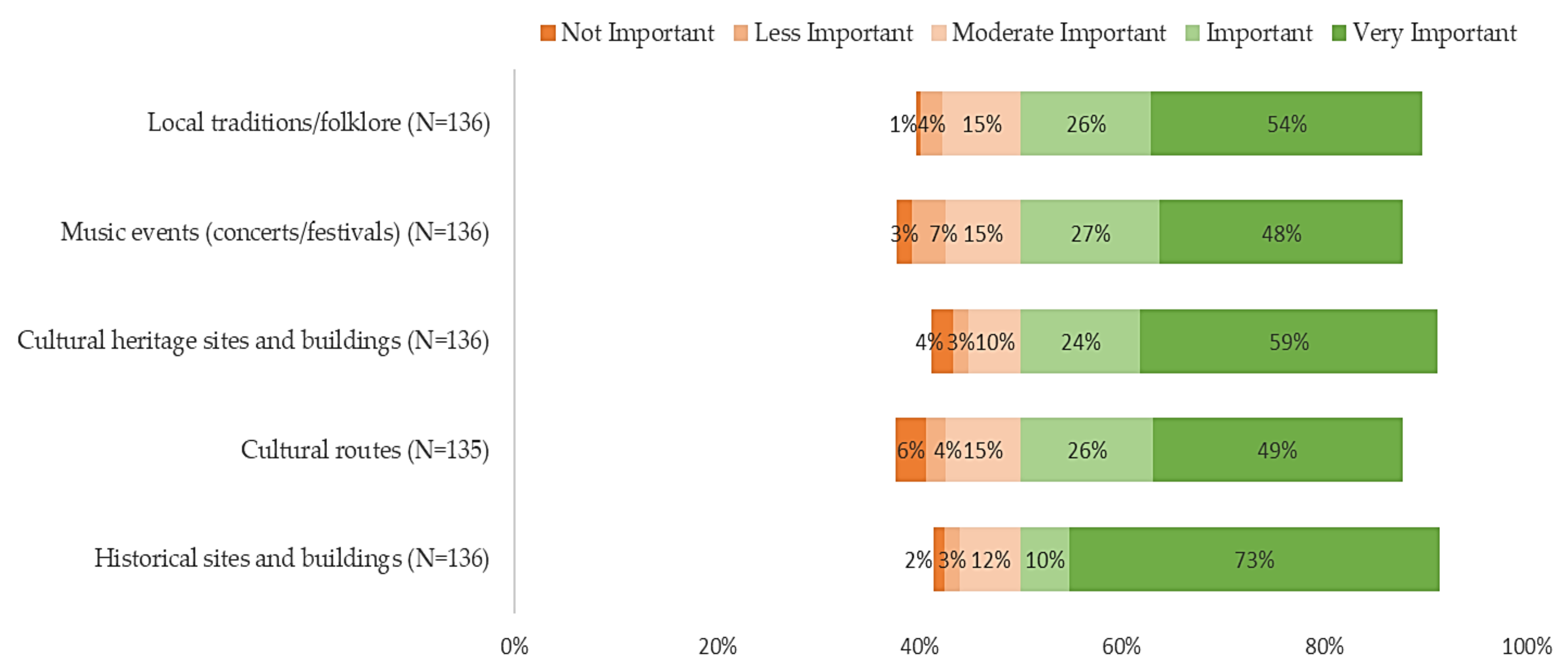

The majority of the resident respondents of the three Cycladic islands stated that they considered “Historical sites and buildings” and “Cultural heritage sites and buildings” to be the two most significant cultural attraction categories for their islands, followed by “Local traditions/folklore”, then by “Music events” and next by “Cultural routes” (

Figure 11). The islands of Andros, Santorini and Syros all boast important archaeological sites of global significance, such the world-famous Akrotiri site in Santorini or the site of the ancient city of Palaiopolis in Andros. Syros also features a rich heritage of industrial cultural sites (including those pertaining to the long tradition of ship building on the island) and the famous neoclassical-style buildings of the 19th and early 20th centuries in Hermoupolis. Museums score as the fourth most important site category cited. Interestingly, in many cases, residents admitted that they had never visited the museums in their region.

4.9. Businesses’ Perceptions on Cultural Tourism in the Area

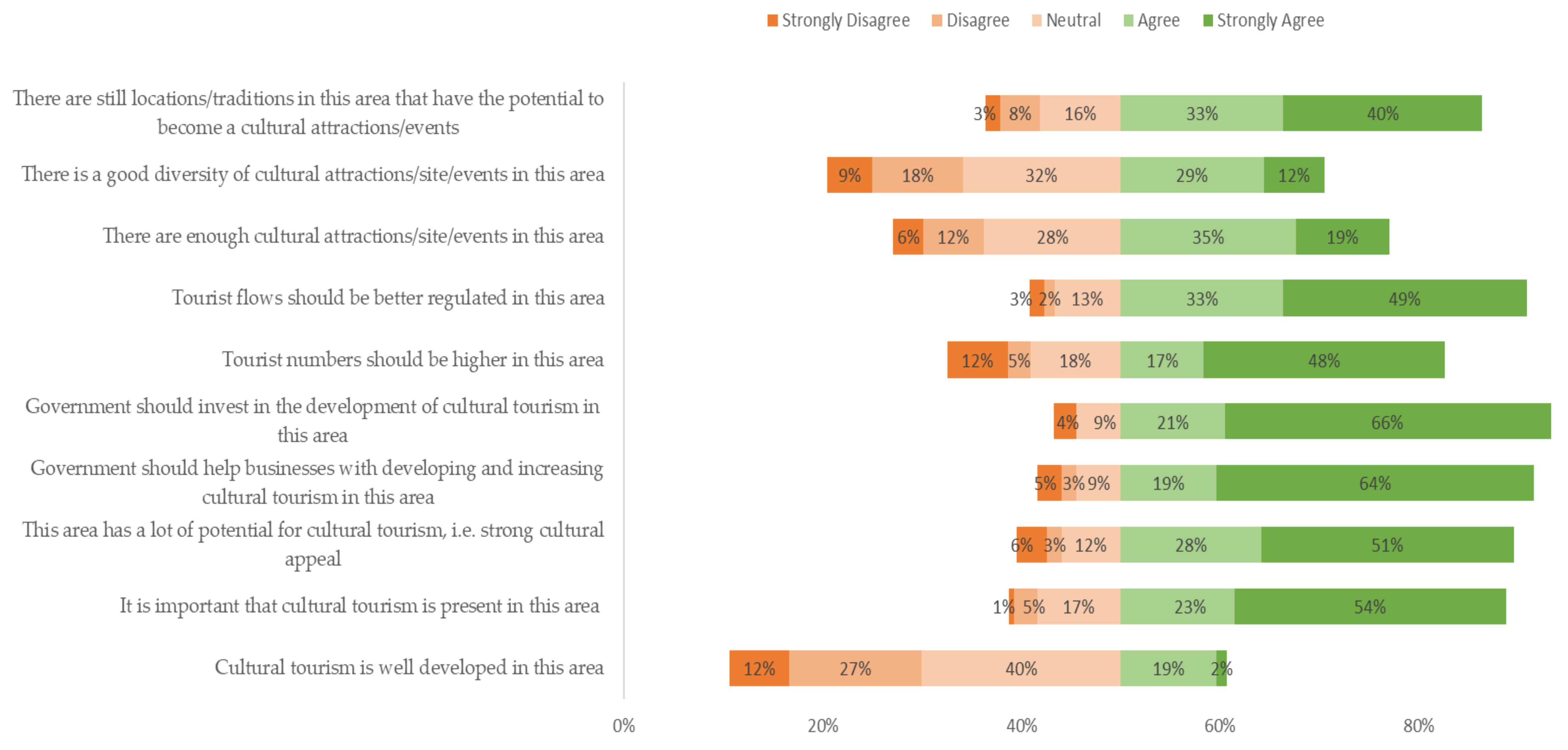

In the responses we received for this question, interest in and concern about (cultural) tourism, as well as the inclusion of more cultural attractions in the tourism product and the perceived significance of the government’s role in these, run high (

Figure 12). Specifically, 66% of our interviewed business representatives stated that they strongly agreed that “Government should invest in the development of cultural tourism in the area”, followed by 64% of them also strongly agreeing that “Government should help businesses with developing and increasing cultural tourism in this area”. A total of 54% of them stated that they strongly agreed with the statement that “It is important that cultural tourism is present in this area” and 51% also strongly agreed with the high potential of cultural tourism in the area. Most responses to the other questions/statements were fairly evenly distributed among the different answer categories, with the exception of responses vis-à-vis the statement “Cultural tourism is well developed in this area”, where most of our respondents had a rather negative opinion, thus reinforcing the previous findings (question 3).

4.10. Factors of Economic Improvement in the Area, According to Businesses

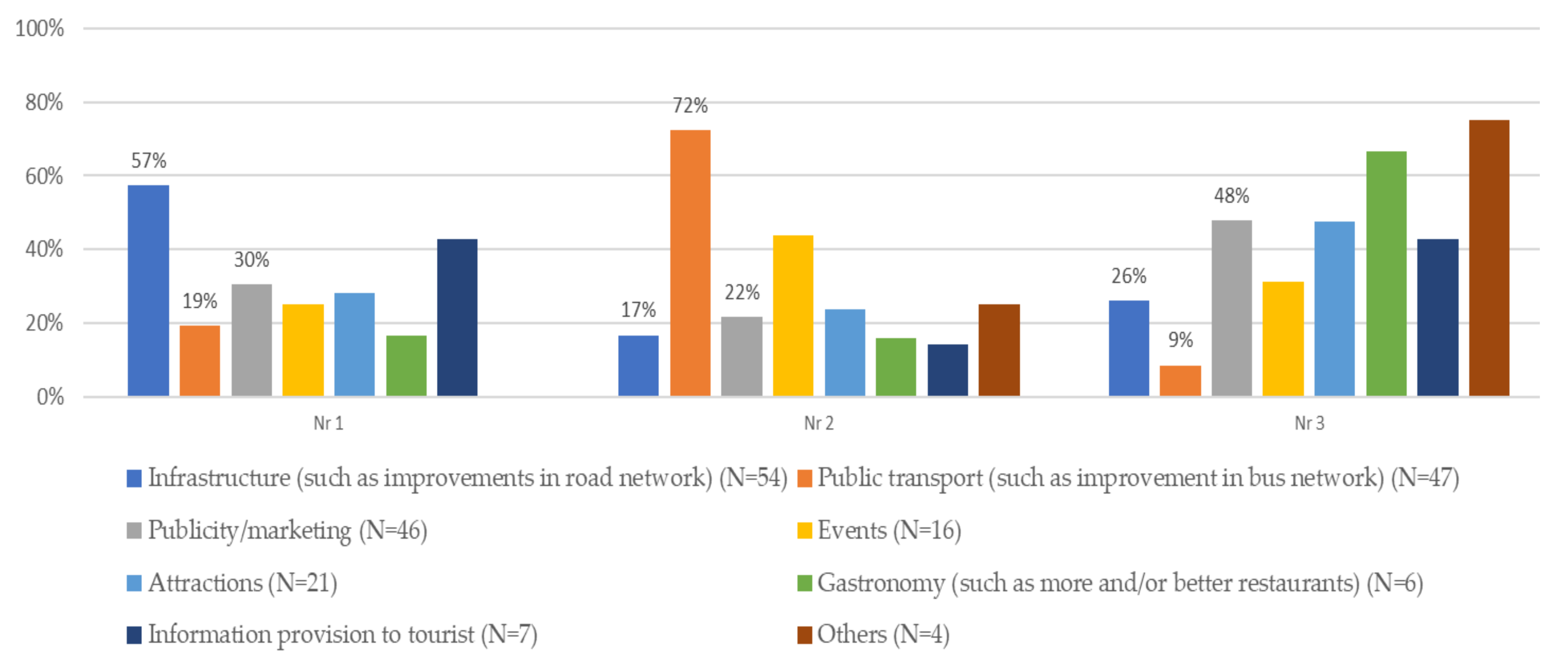

When asked to provide three factors which, according to their opinion, would lead to local economic improvement, business representative respondents emphasized basic infrastructures as the most significant factor for the improvement of the standard of living for both tourists and the islands‘ permanent population (

Figure 13). They specifically rated “Infrastructure (such as improvements in the road network)” as the first most important aspect for economic improvement with 57%, followed by “Information provision to tourists” with 43% and then several other provisions relating to tourism promotion and attraction. The second most important factor, according to their opinion, was “Public Transport” (72%), followed by “Events” (44%) and “Attractions” (24%), very much in line and in agreement with their first reportedly most important factor. The third most important factor, as offered by the business representatives, was a series of several aspects mainly pertaining to the tourism sector, including the categories “Other” (75%), “Gastronomy” (67%), “Publicity/marketing” (48%) and “Attractions” (48%).

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the interrelationships between culture and tourism in the context of cultural tourism, and to link them primarily with an assessment of the current situation of and future implications for cultural tourism and secondarily with prospects of cultural sustainability in three Greek islands, from a bottom-up perspective, namely that of local residents, businesses and tourists. We proceeded to explore these interrelationships and links through the perceptions of the survey participants with the aid of two research questions, the first one referring to the interrelationships of local culture and incoming tourism and the second one referring to their interlinkages with cultural, and overall local, sustainability. We relied on specific questionnaire questions in order to respond to the first research question, whereas we attempt to draw our conclusions regarding the second research question on the basis of the sum of the findings presented in this paper and the insights from the researchers’ participant observation (August–September 2020).

With regard to the first research question and in line with the relevant bibliography, the results derived from our questionnaire survey point to a very broad acknowledgment of the significant role of culture in local tourism development, as well as of the implications/repercussions of tourism for local culture [

2,

6,

15,

17,

32,

50,

60]. This outcome was indicated in the residents’ opinions and in the tourists’ travel motives, the latter’s interest in visiting specific categories of cultural tourism attractions, events, sites, etc. and in their considerably high degree of satisfaction with the aspects of local cultural tourism (questions 1, 2, 3). The most significant cultural attractions for tourism purposes emerged as the well-established and widely known and promoted historical and cultural heritage sites/buildings and slightly less so the intangible destination assets such as local traditions, folklore and arts events. However, tourists also declared that the diversity of cultural activities, the balance of price versus offer and the number of cultural activities provided in the area were, to a high extent, inadequate or lacking. We obtained similarly positive findings, upholding the significance of culture for tourism, from the best part of the surveyed businesses (question 4) in our study area. However, it is important to note that, according to the business representatives, these visitors, by and large, did not visit these islands primarily for their cultural attractions (but rather for 3Ss tourism) and were consequently rather disinclined to pay more for them in order to support the local economy. Nonetheless, it appears that businesses valued the cultural heritage and other aspects of their destinations and acknowledged the visitors’ stated importance of and interest in such attractions, sites and events. Furthermore, unsurprisingly, and in accordance with other similar research findings [

15,

19,

61,

62], local residents professed that they acknowledged that tourism certainly has an impact on local culture, although their opinions were rather spread out between positive and negative views of tourism’s impacts on culture (question 5), although they declared that they largely did not mind tourism-related nuisance to their island communities (question 6), indicating an openness vis-à-vis sustained, or even increased, tourism growth.

Taking into consideration that the majority of our interviewees were domestic tourists, the answers we received were in accordance with how Greek tourists choose to spend their holidays [

38,

47,

53,

56]. For example, local traditions and religious feasts/festivals are very popular events to attend for all ages and types of Greek tourists. Foreign repeat tourists also become aware of these events and usually seek to attend them, too. These celebrations, which are normally dedicated to the patron Saint of an island or a specific area, include attending mass, followed by food and wine consumption, live local music and dance. The celebrations usually take place outdoors during the summer months and become significant meeting points and opportunities for both locals and tourists to get together and feast. Taken all together, such cultural attractions become a most significant pole of tourist attraction for these islands, constituting a competitive advantage versus other destinations [

47,

60]. Obviously, as the Cycladic islands are famous for their crystal-clear waters and beautiful beaches, enjoying the sea and sun generally remains the most important visitation motive, which also generally explains the seasonal character of Cycladic tourism [

13,

47,

54,

61]. As regards the opposite relationship, namely tourism’s repercussions on and implications for local culture, on the one hand, answers tended to be more mixed, in line with other tourism research [

16,

50,

61]. On the other hand, however, locals did not seem to mind the presence of tourism amidst them very much, a finding which is also in line with other relevant research, illustrating the primacy of the economic significance of tourism over other tourism-related concerns for locals in popular Greek island destinations [

13,

57,

61].

With regard to the second and most significant research question of our study, cultural tourism (questions 7, 9) and local culture as part of the tourist product (question 8) were both viewed in a very positive light for the area and island communities, by both the residents and the local business representatives. These responses reveal a very significant role assigned to cultural tourism as regards the establishment and enhancement of local cultural sustainability. All in all, residents of all three islands seemed to acknowledge the importance of the cultural sites and attractions of their islands for the purposes of cultural tourism development, especially those that had already received attention by the Greek state and the international community (i.e., historical/archeological sites/buildings and local traditions/folklore). These survey findings point to the further possibilities of these destinations’ cultural tourism development and expansion, targeted to different markets and interests in cultural tourism. For instance, future destination planning, management and marketing could target those tourist groups which seem to be less attracted to certain cultural activities, i.e., focus on and cater differentially to more (versus less) specialized tourist needs and demands for higher quality or specific expectations for a certain festival activity or folklore, etc.

It was obvious that there are problems and deficiencies with the status quo, as deduced from the received responses (question 9). Specifically, there was general agreement among the business representatives interviewed as to the importance of the development of the islands’ unfulfilled potential for cultural tourism growth for the benefit of tourism and the economy, more generally, and culture, more particularly. However, it was generally clear that at least those businesses participating in the survey had not yet succeeded in responding to this tourist demand and destination potential, as regards the cultural tourism product that they offer. Unsurprisingly [

36,

38,

53,

58], the interviewees also overwhelmingly supported the need for government tourism-related support, funding and regulation of cultural activities, heritage and infrastructure and seemed to be generally demanding more governmental presence in local cultural tourism development (question 9). In other words, they prioritized the role of government as the central regulating institution, in matters of local/regional cultural and overall sustainability (problems, prospects, opportunities and threats). The survey participants seemed to clearly acknowledge the low degree of local cultural development so far, although they stated that they did not necessarily want more tourism, in general. Rather, they showed that they were in favor of developing cultural tourism further and disagreed with statements that there were already enough or diverse enough cultural attractions/sites/events in the area (question 9). In this way, they indicated that they were cognizant of and sensitive about issues of local cultural sustainability, which they deemed could be further improved with the right measures, without the compromise of increasing general tourism arrivals. Furthermore, after a long period of depression in the country, island residents and tourism- or culture-related businesses appeared to have taken the situation in their hands, in the relative absence of the state in most aspects related to cultural tourism planning and management.

These findings are consolidated and reinforced, according to the opinions of the business representatives (question 10), by the fact and general perception that the Cyclades lack adequate and satisfactory road infrastructure and public transport [

38,

53,

61]. The latter two aspects were rated very highly by these interviewees as necessary factors for the area’s economic improvement. Such responses showed the high degree of concern of our study participants for the state and potential of their area’s overall sustainability. It is also evident in these responses that better promotion of the islands and/or the further development of their cultural activities/attractions were also broadly thought to play a very important role towards economic improvement and thus both cultural and overall local sustainability (question 10). These results were further consolidated and verified with the aid of two additional open-ended questions, as follows.

The first one was addressed to the residents and regarded their opinion of the destination’s profit from cultural tourism. Most of them acknowledged the importance of the historical and cultural heritage of their area for tourism and expressed their support for further development by both local and national authorities and relevant stakeholders. They all seemed to agree that investing in and promoting cultural tourism can improve the brand of the destination, minimize ‘mass tourism’ and attract more niche markets, as well as extend the tourism season. Consequently, and in line with other such research findings on alternative tourism in the Greek islands [

36,

38,

59], a large number of respondents linked cultural tourism with economic benefits, such as increased income, job positions and further investments in the islands. Others focused on the benefits that cultural tourism could have on everyday life and the standard of living for the local societies. Resident respondents also stated that they wished they felt more connected to their heritage and built closer bonds with it through cultural activities and socializing. In general, all respondents tended to agree that cultural tourism is potentially the most obvious and promising means to upgrade the Cycladic tourism product, as well as to raise both the economic revenues and the cultural conditions of their islands.

The second—and complementary—open-ended question was addressed to the tourists and regarded their opinion vis-à-vis missing elements from the area as a tourism destination (i.e., tourism facilities, infrastructures and other general improvements). A great number of them stressed the importance of infrastructure for the islands, such as road connections, public transport and visual and performing arts spaces/centers/galleries, which, if improved, can seriously contribute to the development of cultural tourism on these islands [

38,

50]. Most of the tourists interviewed referred to a lack of information and proper advertising in contrast with the high level of cultural richness and heritage of the Cyclades. They pointed out that it is difficult to find relevant information on publicly available and local internet websites, as cultural events and festivals are usually promoted by private initiatives/advertisements and not publicly, i.e., via The Greek Board of Tourism. A number of tourists expressed their strong interest in more historical and archaeological courses/seminars, workshops and events. This interest was accompanied by their surprise at how this sector has not been adequately developed yet, proffered together with suggestions for organizing and establishing more children- and family-oriented types of events.

In such statements, once again, we encounter a stated awareness of serious shortcomings in the local sector of culture—both in itself and for tourism. We also encounter the acknowledgment of and advocacy for the significance of culture—in conjunction with other general development interventions—towards the future achievement of local cultural and overall sustainability. Admittedly, the sustainability target for these islands ought to be a combination model of conventional and alternative/special-interest tourism development, taking into account (a) the tourist side’s demands and interests, (b) the local communities’ needs and aspirations and (c) the particularities of the Cycladic geography, history and culture, in order to make the most of the uniqueness of both the natural and human environment of the Cyclades [

50,

54,

62].

6. Conclusions

Culture and tourism emerge from this exploratory study as positively interlinked in the minds of the locals, the visitors and the entrepreneurs involved in cultural tourism and tourism more generally in the Cyclades. The culture–tourism relationship is generally viewed as holding great potential for all sides involved and for local cultural and overall sustainability, despite the broad acknowledgement that the great potential for cultural sustainability in the study area is, to date, far from met. The role of tourism in local cultural development, management and appropriation is also viewed by the study participants with a degree of trepidation and ambivalence, in line with Soini and Birkeland’s perspective of ‘economic viability’ and tourism’s actual contribution and variable links to other aspects of local cultural sustainability (e.g., by generating revenues, there might be an increased incentive for further and better cultural resource protection and preservation). Tourism, after all, refers first and foremost to an economic activity, and the most crucial one at that, for the Cycladic Islands of Greece, which are highly dependent on tourism for their economic sustenance and development. Other perspectives of Soini and Birkeland’s framework of cultural sustainability analysis were also honored by the survey participants, in their views and perceptions of the role of culture in tourism and vice versa, and in their understanding of the potential of cultural tourism development for local cultural sustainability: specifically, cultural heritage, cultural vitality, locality and perhaps eco-cultural resilience [

10].

The practical contribution of this exploratory study refers to the generation and analysis of such knowledge, views, prospects, etc., for purposes of appropriation from all sides involved—including stakeholders, professionals and decision-makers—towards more sustainable tourism and cultural-destination planning, management, development, preservation, consumption and local life improvement. However, as this research survey was undertaken in the context of a broader research project (SPOT) with goals supporting and referring to general sustainability, more focused research, specifically on cultural sustainability, ought to be conducted in order to tackle this latter area of inquiry more effectively. Furthermore, as far as future research is concerned, such research ought to be replicated in additional Aegean/other islands, in mainland locations in Greece and/or other tourist destinations, while it could be extended in content and depth, as well as through its employment of larger and broader research samples, besides, of course, being replicated over time, for comparative purposes.

In conclusion, the originality of this study lies in its synthetic, comparative and nuanced research scope, combining an exploration and analysis of the relationship between culture and tourism through the eyes of travelers, locals and tourism businesses, in these three Aegean islands, towards a bottom-up understanding of this relationship and of its role in cultural tourism development and ultimately its role in local cultural sustainability. Such a research undertaking comes at the present transitional time of a fluid and uncertain post-pandemic future for tourism and of various newly emerging forms of broadly accessible tourism/leisure pursuits and activities, but also at a time of great opportunities stemming from a generalized concern for sustainability and ‘green’/soft/mild development triggered by climatic crisis. Accordingly, rising rates and globalizing patterns of mobility and consumption continue to necessitate renewed and more in-depth scientific investigation into conventional as well as alternative sites and attractions sought by visitors, not least in already established global tourist destinations such as the Cyclades.