The Importance of Stakeholders in Managing a Safe City

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definitions of a Safe City

2.2. Stakeholders—A Description and Roles

- Systematization of stakeholders’ expectations based on the hierarchy of values and Key Performance Areas (KPA) [66];

- Distribution of stakeholders according to potential threat or willingness to cooperate [67];

- Assessment of the awareness, support, and influence of leading stakeholders on communication strategy and evaluation of stakeholder satisfaction [68];

3. Research Section

3.1. Methodology

3.2. Limitations of the Research

3.3. Characteristics of Respondents

3.4. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schaffers, H.; Komninos, N.; Palloot, M.; Trousse, B.; Nilsson, M.; Oliveira, A. Smart Cities and the Future Internet: Towards Cooperation Framework for Open Innovation. In The Future Internet. Future Internet Assembly 2011: Achievements and Technological Promises; Domingue, J., Galis, A., Gavras, A., Zahariadis, T., Lambert, D., Cleary, F., Daras, P., Krco, S., Müller, H., Li, M.-S., et al., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 431–446. [Google Scholar]

- Allwinkle, S.; Cruickshank, P. Creating Smart-er Cities: An Overview. Urban Technol. 2011, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, M. The Role of Smart City Characteristics in the Plans of Fifteen Cities. J. Urban Technol. 2017, 24, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.N.; Khan, M.; Han, K. Towards sustainable smart cities: A review of trends, architectures, components, and open challenges in smart cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneć, R. The Role of Stakeholders in Shaping Smart Solutions, in Polish Cities. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 1981–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perboli, G.; Rosano, M. A Taxonomic Analysis of Smart City Projects in North America and Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigea, A.; Papadopoulou, C.A.; Panagiotopoulou, M. Tools and Technologies for Planning the Development of Smart Cities. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristvej, J.; Lacinák, M.; Ondrejka, R. On Smart City and Safe City Concept. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2020, 25, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lara, A.P.; Moreira Da Costa, E.; Furlani, T.Z.; Yigitcanlar, T. Smartness that matters: Towards a comprehensive and human-centred characterisation of smart cities. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2016, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Townsend, A. Smart City: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for New Utopia; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Linders, D. From e-government to we-government: Defining a typology for citizen coproduction in the age of social media. Gov. Inf. Q. 2012, 29, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozario, S.D.; Venkatraman, S.; Marimuthu, M.; Khaksar, S.M.S.; Subramani, G. Creating Smart Cities: A Review for Holistic Approach. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2021, 4, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, I.; Nygren, K.G. Contesting city safety—Exploring (un)safety and objects of risk from multiple viewpoints. J. Risk Res. 2020, 24, 1251–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacinák, M.; Ristvej, J. Smart City, Safety and Security. Procedia Eng. 2017, 192, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart Cities Study. International Study on the Situation of ITC, Innovation and Knowledge in Cities; The Committee of Digital and Knowledge-Based Cities of UCLG: Bilbao, Spain, 2012; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Caragliu, A.; Nijkamp, P. Smart Cities in Europe. J. Urban Technol. 2009, 18, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart Cities and Communities. Key Messages for the High-Level Group from the Smart Cities Stakeholder Platform Roadmap Group. 2013. Available online: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/28452233/key-messages-to-the-high-level-group-smart-cities- (accessed on 22 September 2020).

- Axis Communications. A Smart City is a City, where People Feel Safe. Brochure Axis Communications. 2015. Available online: https://www.axis.com/files/brochure/bc_casestudies_safecities_en_1506_lo.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- Huawei Smart City Solution. Brochure Huawei Technologies; Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd: Shenshen, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Borker, G. Safety First: Perceived Risk of Street Harassment and Educational Choices of Women; Job Market Paper Department of Economics, Brown University: Providence, RI, USA, 2017; pp. 12–45. [Google Scholar]

- Petrella, L. Inclusive city governance––A critical tool in the fight against crime. Habitat Debate 2007, 13, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, G.H. What Are the World’s Safest Cities? Available online: https://www.movehub.com/blog/worlds-safest-cities/ (accessed on 7 November 2020).

- Finka, M.; Ondrejička, V.; Jamečný, Ľ. Urban Safety as Spatial Quality in Smart Cities; Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe City Index 2019. Urban Security and Resilience in an Interconnected World; The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited: London, UK; New York, NY, USA; Hong Kong, China; Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Safe City Index 2021. Urban Security and Resilience in an Interconnected World; The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited: London, UK; New York, NY, USA; Hong Kong, China; Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov, V.; Robnik, A.; Terekhov, A. “Safe City”––An Open and Reliable Solution for a Safe and Smart City. Elektrotehniški Vestn. 2012, 79, 262–267. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, L. Stakeholder Relationship Management. In A Maturity Model for Organisational Implementation; Gower Publishing Ltd.: Burlington, VT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wereda, W. Model of building stakeholder engagement in the functioning of the organization––Trust and risk. Ann. UMCS Sec. H Oeconomia 2018, 52, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abrams, F. Management Responsibility in a Complex World. In Business Education for Competence and Responsibility; Chapel, T.C., Ed.; Hill University of North Carolina Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Silbert, T.H. Financing and factoring accounts receivable. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1952, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, E. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Ansoff, H.I. Corporate Strategy; Penguin Books: Harmondsworth, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Cyert, R.M.; March, J.G. A Behavioral Theory of the Frim; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; Reed, D.L. Stockholders and Stakeholders: A New Perspective on Corporate Governance. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1983, 23, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argandoña, A. The stakeholder theory and the common good. J. Bus. Ethics 1998, 17, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhenman, E. Företagsdemokrati Och Företagsorganisation; SAF Norstedt, Företagsekonomiska Forsknings Institutet: Stockholm, Sweden, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, W.C. Creatures, corporations, communities, chaos, complexity: A naturological view of the corporate social role. Bus. Soc. 1998, 37, 358–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slatter, S.S. Strategic planning for public relations. Long Range Plan. 1980, 13, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, B.; Shapiro, A.C. Corporate Stakeholders and Corporate Finance. Financ. Manag. 1987, 16, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodako, K. Foresight W Zarządzaniu Strategicznym; C.H. Beck: Warsaw, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. The Politics of Stakeholder Theory: Some Future Directions. Bus. Ethics Q. 1994, 4, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.L.; Lewis, W.F. A Stakeholder Approach to Marketing Management Using the Value Exchange Models. Eur. J. Mark. 1991, 25, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, S.N. The Stakeholder Theory of the Firm and Organizational Decision Making: Some Propositions and a Model. In Proceedings of the International Association for Business and Society, San Diego, CA, USA, 19–21 March 1993; pp. 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Starik, M. Is the Environment an Organizational Stakeholder? Naturally! In Proceedings of the International Association for Business and Society, San Diego, CA, USA, 18–21 March 1993; pp. 921–932. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, M. A Risk-Based Model of Stakeholder Theory. In Proceedings of the Second Toronto Conference on Stakeholder Theory; Center for Corporate Social Performance & Ethics, University of Toronto: Toronto, Canada, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, J. FOCUS: Stakeholder Responsibilities: Turning the ethical tables. In Business Ethics: A European Review; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 3, pp. 212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, M.M. Whose interests should corporations serve. In Ownership and Control: Rethinking Corporate Governance for the Twenty-First Century; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 202–234. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implication. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What really Count. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson Centre for Business Ethics & Clarkson. Principles of Stakeholder Management; Clarkson Centre for Business Ethics, Joseph L. Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto: Toronto, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, K. The moral basis of stakeholder theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 26, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendry, J. Economic contracts versus social relationships as a foundation for normative stakeholder theory. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. Wiley Online Libr. 2001, 10, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orts, E.W.; Strudler, A. The ethical and environmental limits of stakeholder theory. Bus. Ethics Q. JSTOR 2001, 12, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R. Stakeholder legitimacy. In Business Ethics Quarterly; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; Volume 13, pp. 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, D.; Paton, R. Responding to competing narratives: Lessons for project managers. Int. J. Proj. Manag. Elsevier 2004, 22, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R. Results from an International Stakeholder Survey on Farmers’ Rights; Fridtj of Nansen Institute: Lysaker, Norway, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, L.; Walker, D.H.T. Visualizing stakeholder influence—Two Australian examples. Proj. Manag. J. 2006, 37, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olander, S. Stakeholder impact analysis in construction project management. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2007, 25, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.H.T.; Bourne, L.; Rowlinson, S. Stakeholders and the supply chain. In Procurement Systems––A Cross Industry Project Management Perspective; Walker, D.H.T., Rowlinson, S., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2008; pp. 70–100. [Google Scholar]

- Couillard, J.; Garon, S.; Riznic, J. The logical framework approach millennium. Proj. Manag. J. 2009, 40, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanienko, J.; Piotrowski, W. Zarzadzanie. Tradycja i Nowoczesność; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Szwajca, D. Zarządzanie Reputacją Przedsiębiorstwa. Budowa i Odbudowa Zaufania Interesariuszy; CeDeWu: Warsaw, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide), 6th ed.; Project Management Institute: Newton Square, MA, USA, 2017.

- Łudzińska, K.; Zdziarski, M. Interesariusze w opinii prezesów zarządów polskich przedsiębiorstw. KNOB 2013, 2, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B.; Buchholtz, A.K. Business & Society, Ethics and Stakeholder Management, 7th ed.; South-Western Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, A.; Guthrie, J.; Steane, P.; Pike, S. Mapping stakeholder perceptions for a third sector organization. J. Intellect. Cap. 2003, 4, 505–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, G.T.; Nix, T.W.; Whithead, C.J.; Blair, J.D. Strategies for assessing and managing organizational stakeholders. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1991, 5, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R.; Kristoffer, V.; Thurloway, L. The Project Manager as Change Agent; McGraw-Hill Publishing: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Caniato, M.; Vaccari, M.; Visvanathan, C.; Zurbrügg, C. Using social network and stakeholder analysis to help evaluate infectious waste management: A step towards a holistic assessment. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 938–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarządzanie Projektami––Wyzwania i Wyniki Badań; Trocki, M.; Bukłaha, E. (Eds.) SGH: Warsaw, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Briner, W.; Hastings, C.; Geddes, M. Project Leadership; Gower Publishing Company: Gower, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stakeholder Circle. 2011. Available online: http://www.stakeholder-management.com (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Ya, S.; Rui, T. The Influence of Stakeholders on Technology Innovation: A Case Study from China. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Management of Innovation and Technology, Singapore, 21–23 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wereda, W.; Paliszkiewicz, J.; Lopes, T.; Wozniak, J.; Szwarc, K. Intelligent Organization towards Contemporary Trends in the Process of Management—Selected Aspects; Publishing House of WAT: Warsaw, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mały Rocznik Statystyczny Polski 2019; Główny Urząd Statystyczny (Central Statistical Office): Warsaw, Poland, 2019; p. 102.

| Search Term | Web of Science | Scopus | Google Scholar |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safe city | 26,179 (966) | 11,336 (3128) | 3,850,000 |

| Stakeholders in the city | 13,703 (1519) | 10,480 (5554) | 1,440,000 |

| Security of habitants | 29 (5) | 32 (10) | 64,000 |

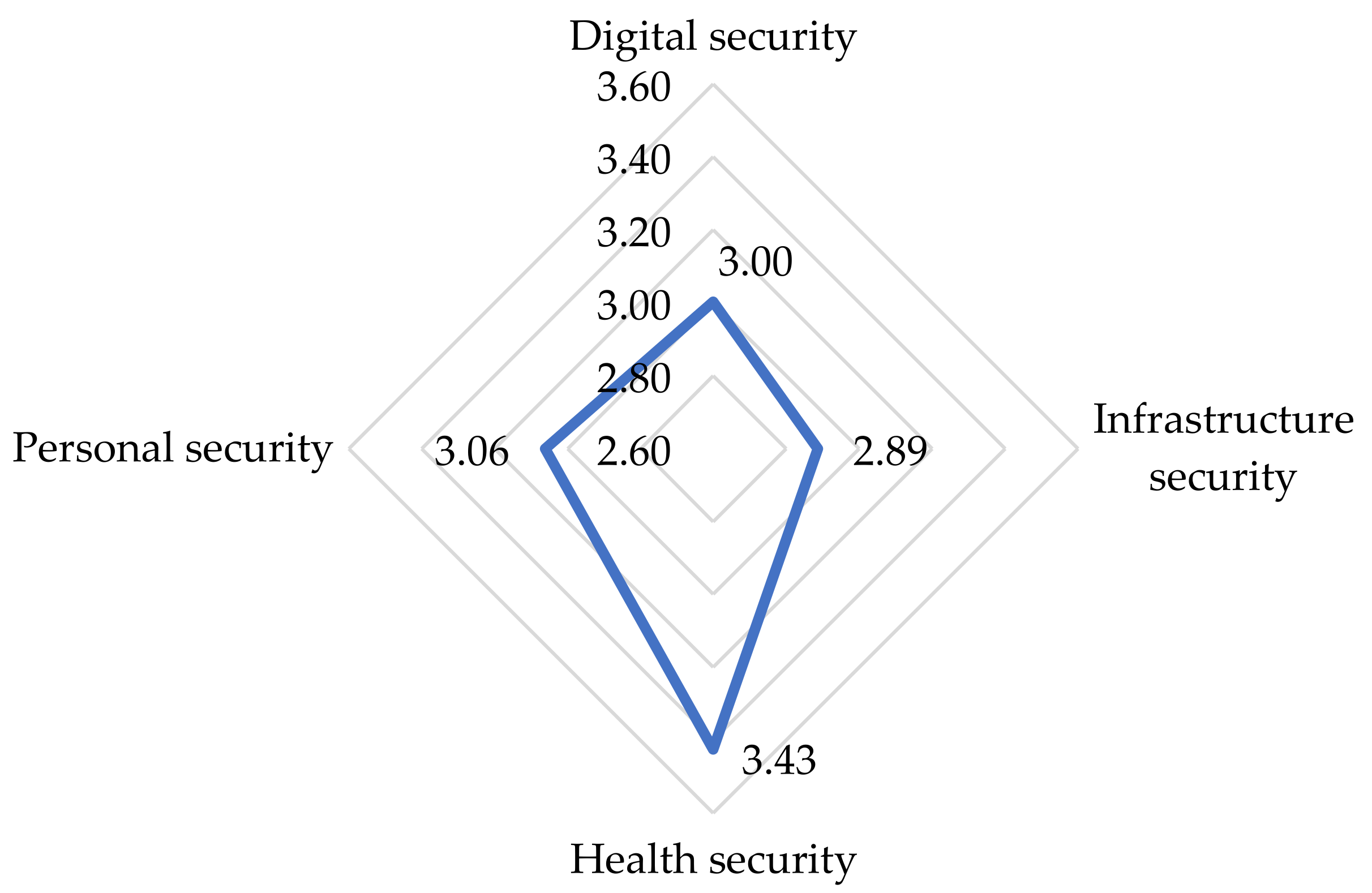

| Overall Score | Digital Security | Health Security | Infrastructure Security | Personal Security |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

| 2021 | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

| No. | Date | Author | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1951 | Abrams | The basic responsibilities of management derive from general obligations to maintain a fair and workable balance between the claims of the various groups concerned [29]. |

| 2. | 1952 | Silbert | First use of the word stakeholder in the context of finance and factoring [30]. |

| 3. | 1959 | Penrose | Defining the nature of the organization in the form of human collections and contacts between participants and stakeholders [31]. |

| 4. | 1963 | Stanford Research Institute | Groups without whose support the organization could not exist (Stanford Research Institute 1963). |

| 5. | 1965 | Ansoff | The organization’s objectives should be determined by balancing the conflicting claims of the various “stakeholders” of the company. The organization has obligations to all these actors and must configure its objectives in this way to give everyone a degree of satisfaction [32]. |

| 6. | 1983 | Freeman and Reed | In the broad sense: they can influence the achievement of the organization’s objectives for those affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives; in the narrow sense: those on which the organization’s continued existence depends [34]. |

| 7. | 1984 | Freeman | They may influence or be influenced by the achievement of the organization’s goals [41]. |

| 8. | 1991 | Miller and Lewis | Stakeholders are people who can help or harm the organization [42]. |

| 9. | 1993 | Brenner | Entities with a legitimate, relevant relationship with the organization, such as exchange transactions and influence on activities and moral responsibility [43] |

| 10. | Starik | Naturally occurring entities that are influenced or influenced by the organization’s performance [44] | |

| 12. | 1994 | Clarkson | They carry some form of risk as a result of investing some kind of capital, human, or financial or bear the risk as a result of the company’s actions [45]. |

| 13. | Mahoney | Passive stakeholders who have moral claims against the organization relating to non-violation and non-infringement and active stakeholders whose claims are more social [46]. | |

| 14. | 1995 | Blair | All parties who have contributed to the company and who, as a result, have risky investments and are highly specialized in the company [47]. |

| 15. | Donaldson and Preston | Persons having direct or implied contracts with the company. Identified by actual or potential damages and benefits they experience or expect to experience as a result of the company’s actions or their own interactions with the company [48]. | |

| 16. | Mitchell, Agle, and Wood | Legitimate or urgent claim against the company or authority to influence the company, voluntary members of the cooperation scheme for mutual benefit, […] partners seeking a mutual advantage. A claim (standard) can only be justified if it can be approved by all those affected by the standard [49]. | |

| 17. | 1998 | Argandofńia | All those who have an interest in the company (so that the company in turn may have an interest in meeting their requirements) [35]. |

| 18. | Frederick | All members of a community that are interested in what the organization does [37]. | |

| 19. | 1999 | Clarkson Centre for Business Ethics | Interested parties: they bear certain risks and may therefore gain or lose something as a result of the company’s activities [50]. |

| 20. | 2000 | Gibson | Groups and persons, with whom the organization has relations or interdependencies, and any person or group that may influence or be influenced by actions or decisions, a politician, and the organization’s practices or objectives [51]. |

| 21. | 2001 | Hendry | Entities in relationships based on moral considerations […] Relationships that cannot be reduced to contractual or economic relationships alone. They include social features such as interdependence [52]. |

| 22. | Orts and Strudler | Business participants with some kind of economic contribution that is subject to risk [53]. | |

| 23. | 2003 | Phillips | Normative stakeholders: those for whose benefit the company should be managed. Torch Stakeholders: they can potentially influence the organization and its normative stakeholders [54]. |

| 24. | 2004 | Boddy and Paton | Stakeholders are individuals, groups, or institutions with an interest in the project and who may influence its outcome [55]. |

| 25. | 2005 | Andersen | Person or group of persons affected or likely to be affected by the project [56]. |

| 26. | 2006 | Bourne and Walker | Stakeholders are individuals or groups who have an interest or some aspect of rights or ownership in a project and can contribute to or influence the results of the project [57]. |

| 27. | 2007 | Olander | A person or group of persons who are interested in the success of the project and the environment in which the project operates [58]. |

| 28. | 2008 | Walker, Bourne and Rowlinson | Stakeholders are individuals or groups who have an interest, ownership, or some kind of rights towards the project and may contribute to or be influenced by the project [59]. |

| 29. | 2009 | Couillard, Garon and Riznic | Entities or persons who are or will be influenced directly or indirectly by the organization [60]. |

| 30. | Bourne | Individuals or groups that are or that may be affected by the work or its results at this particular point in the organization’s life cycle [27]. | |

| 31. | 2013 | Bogdanienko and Piotrowski | The organization’s stakeholders are significant individuals, interest (pressure) groups, coalitions, or organizations that have their own interests in the functioning of a particular organization and can influence it [61]. |

| 32. | 2016 | Szwajca | The author defines stakeholders as individuals or groups that may influence or be influenced by various activities that affect the reputation of the organization [62]. |

| 33. | 2017 | Project Management Institute | People, groups, and organizations that may influence or be influenced by the decision, action, or outcome of the project [63] |

| Stakeholders with primary impact and direct involvement (key) | |

| 1. Internal and close to them (directly related to the tasks of the company) | Owners, shareholders, management, authorities, employees and their families, former employees, pensioners, applicants, apprentices, members of informal groups in the company, proxies, advisors, supervisory boards, works councils/employee organizations, members in member organizations, and their democratic bodies/authorities. |

| 2. External (more or less directly related to the tasks of the company in question) | Shareholders, members of co-ownership bodies, persons with influence over co-owners, representation of members in the bodies of associations, competitors/industry and non-industry opponents (e.g., those operating in the same labor, capital, know-how, opinion, value, or idea markets), ad hoc competitors, sales representatives and/or other sales and supply intermediaries, development funds, strategic (business) partners, customers/buyers/receivers/users/consumers, cooperatives, their members and associations, banks and other financial institutions, dealers, brokers, lobbying organizations, consulting companies, consumer organizations, employee organizations, trade unions, employers’ associations, other industry and professional communities and business agreements, business associations, advertising, marketing, and public relations agencies, members of social and professional organizations. |

| Second-level stakeholders with indirect (supporting) involvement | |

| Environment of the so-called “Arcade”: general authorities at various levels and regulatory institutions in the economy and social life | Governmental and state bodies, their agendas and members, including members of local government bodies, members of parliament, senators and other politicians acting within the state bodies, various levels of decision-makers/state bodies in the field of social, political, economic, and cultural life and the executors of their policies and decisions among other organizations/regulatory bodies active in the labor and financial markets, ministries relevant to social policy, dialogue bodies of state institutions, financial institutions, fiduciary offices, judicial authorities, consumer/government ombudsmen with interest groups, state employment offices, tax and customs services. |

| Stakeholders with further degrees of impact and further involvement (marginal) | |

| 1. Opinion formers/Environmental opinions | Mass media, journalists, journalists’ organizations, editorial offices, correspondents (including foreign ones), editorial offices of company (company) newspapers, press departments of institutions and companies from the local environment, universities and their authorities, students and their representations, university promotion departments, alumni associations, employers’ and alumni councils, leaders of views and opinions originating from various areas of public life, influential representatives of cultural, educational, political, and religious institutions, creative associations, the audience of influential media, guests visiting companies. |

| 2. Citizens’ initiatives and similar | Non-governmental organizations protecting the environment, civil liberties, and rights, consumer associations, other grassroots institutions of public life, societies working to solve social and health problems, environmental organizations, etc. |

| 3. Corporate and international environment | Diplomatic representations, diplomats, consular departments of embassies, representations of foreign organizations and authorities, affiliations of international organizations.1 |

| Population | City Class | Number of Cities | Population in Cities (in Thous.) | % of the Total Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20,000–49,999 | IV | 134 | 4246.6 | 11.1 |

| 50,000–99,999 | V | 46 | 3116.4 | 8.1 |

| 100,000–199,999 | VI | 22 | 3057.4 | 8.0 |

| 200,000 and more | VII | 16 | 7648.1 | 19.9 1 |

| City Function | Medium Cities | Large Cities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20,000– 49,999 | 50,000– 99,999 | 100.000–199.999 | 200,000 and more | |

| Industrial | 11 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Commercial | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Service | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Recreational and tourist | 6 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Industrial and service | 15 | 10 | 8 | 4 |

| Religious worship | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 1 |

| Advisory Level of influence and relevance of stakeholders | Marginal stakeholders (low impact) 1. 26–2.50 | Church |

| Companies offering insurance services | ||

| Outsourcing companies (e.g., cleaning, property protection) | ||

| Training companies | ||

| Rating companies (companies forming local government ratings) | ||

| Supporting stakeholders (average impact) 2. 51–3.75 | Individual stakeholders | |

| Inspection (PIP, Sanitary, Tax Office, etc.) | ||

| Administrative staff | ||

| Product suppliers | ||

| Banks and financial institutions | ||

| Contractors (service subcontractors) | ||

| Advisory consulting | ||

| Accreditation and certification bodies | ||

| Sponsors | ||

| Local industry associations | ||

| Local politicians | ||

| Local media (press, radio, and television) | ||

| Social media (blogs, web portals, etc.) | ||

| Local business | ||

| Institutions neighboring local government units | ||

| Associations and foundations | ||

| Intermediate institutions in obtaining EU funds | ||

| Companies helping to obtain grants from various funds | ||

| Partner cities | ||

| Key stakeholders (high impact) 3. 76–4.51 | Institutional stakeholders | |

| City Council | ||

| Investors | ||

| Local community | ||

| Managing staff (city president, mayor) |

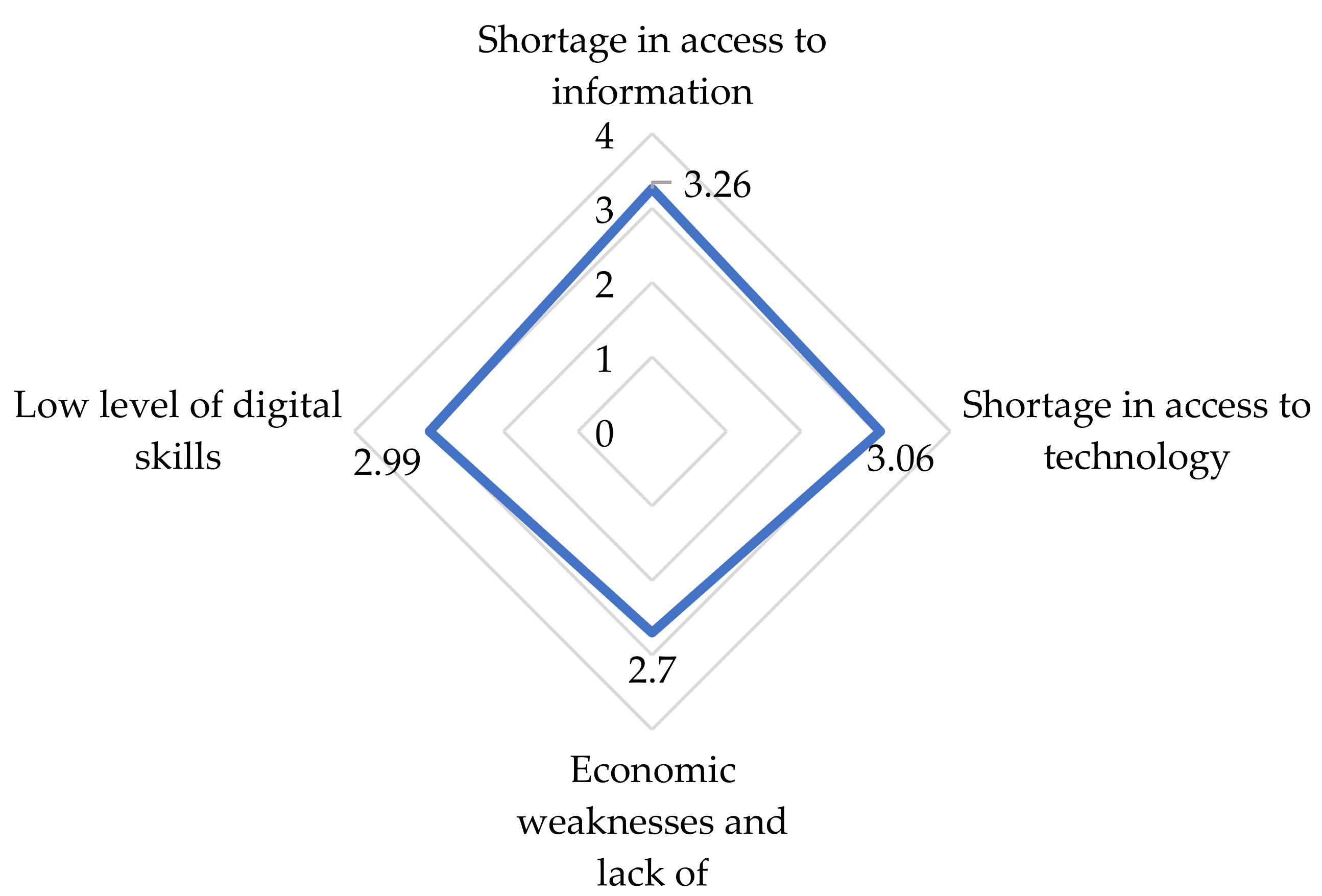

| Digital security | 1. | Information deficiency |

| 2. | Technology deficiency | |

| 3. | Economic vulnerability and lack of competitiveness | |

| 4. | Low level of digital skills | |

| Infrastructure security | 1. | Information deficiency |

| 2. | Inequality of access to opportunities and resources | |

| 3. | High infrastructure deficit | |

| 4. | Lack of diversification in the urban economy | |

| 5. | Lack of accessible and affordable public transport | |

| 6. | Restriction of growth in private car ownership and use | |

| 7. | Very fast urbanization | |

| 8. | Inefficient management of resources | |

| Health security | 1. | Pollution |

| 2. | Social and health services deficit | |

| Personal security | 1. | Low urban institutional potential |

| 2. | Gap between government and society | |

| 3. | Lack of quality in neighborhoods and public spaces | |

| 4. | Threats to cultural identity | |

| 5. | Urban violence and insecurity | |

| 6. | Lack of accessible leisure facilities | |

| 7. | Lack of awareness, commitment, and participation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wereda, W.; Moch, N.; Wachulak, A. The Importance of Stakeholders in Managing a Safe City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010244

Wereda W, Moch N, Wachulak A. The Importance of Stakeholders in Managing a Safe City. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010244

Chicago/Turabian StyleWereda, Wioletta, Natalia Moch, and Anna Wachulak. 2022. "The Importance of Stakeholders in Managing a Safe City" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010244

APA StyleWereda, W., Moch, N., & Wachulak, A. (2022). The Importance of Stakeholders in Managing a Safe City. Sustainability, 14(1), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010244