1. Introduction

Guaranteeing that populations have access to safe drinking water and sanitation, considering the sustainable management of water resources, wastewater and ecosystems while acknowledging the influence of an has been farther from being a utopian dream. Indeed, seeking to “ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all” is an honourable Sustainable Development Goal (SDG)-SDG 6, an integral part of the ‘2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ of the United Nations (UN) [

1]. As a plan of action for people, the planet, and prosperity, the UN reaffirmed its commitment regarding the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation by involving all countries and stakeholders in a path towards world sustainability and resilience [

2].

However, even before the current COVID-19 pandemic began to take its real toll, 26% and 46% of the world’s population still lacked a safely managed drinking water and sanitation service (WSS), respectively; furthermore, 29% remained with no access to a basic handwashing facility and up to 44% of the world’s household wastewater was not safely treated [

3]. According to the same report, the UN disclosed that a worrying 129 countries are not on track to have sustainably managed water resources by 2030, and need to double their current efforts. Therefore, it is clear that there is plenty of room for improvement, as was recently shown by Pereira and Marques [

4]. As a matter of fact, the authors revealed that several countries have moved away from the best practices in terms of SDG 6, with Brazil being the largest and most populated country featured on that list apart from China (whose overall water-use efficiency is low, with plenty of room for improvement [

5,

6]). According to the Brazilian National Sanitation Information System (SNIS, from the Portuguese abbreviation of

Sistema Nacional de Informações sobre Saneamento), 16% of the country’s population does not have access to a water supply network and 46% does not have access to a sanitation service network [

7]. Moreover, SNIS [

7] also notes that 22% of the nation’s collected wastewater is untreated. Ultimately, this reality calls for analysis to provide evidence to managers and regulators on the best practices in the sector, which could promote significant improvements.

In Brazil, with only 4% of WSSs being privately operated, the influence of private entities is rather irrelevant, despite contradicting results with respect to the efficiency of privately managed utilities when compared to that of publicly managed ones: Carvalho and Sampaio [

8] revealed that private WSS operators were more efficient than their public counterparts, but Seroa da Motta and Moreira [

9], da Silva e Souza et al. [

10], and Barbosa et al. [

11] found no evidence of such a reality. In fact, Cetrulo et al. [

12] and Marques and Simoes [

13] had already found evidence of private WSS operators outperforming public WSS operators in Portugal, while lo Storto [

14] and Maziotis et al. [

15] proved that the juridical nature of ownership does not have a statistically significant impact on WSS efficiency in Italy and Chile, respectively. Furthermore, as the fifth largest country in the world, it is important to understand the impact of regional contrasts on the efficiency of WSSs. The North, Northeast, Central-West, Southeast, and South Regions, and their completely different environments and social, cultural, and economic traits, were found to have quite distinct efficiency levels [

11,

16]. In particular, the higher socio-economic development and subtropical climate of the southern regions contrast with the lower socio-economic development and tropical climate of the northern regions. Other factors help explain the tremendous asymmetries found in the country, such as its colonial past and the heterogeneous immigration distribution. Moreover, Brazilian WSSs are managed by entities operating according to three different scopes: local-level, multi-municipal/micro-regional level, and state/regional level. First, local-level entities provide WSSs to a single municipality. Second, multi-municipal/micro-regional level entities provide WSSs to a small number of municipalities. Third, and finally, state/regional level entities provide WSSs to their respective state and are the main WSS providers in the country, providing 78% of water services and 55% of sanitation services [

7], after their creation in the 1970s in search for economies of scale. Previous studies have already pointed towards the higher efficiency of local-level WSS entities [

8,

9,

17,

18], although Sabbioni [

19] showed that state/regional-level WSS entities have a higher efficiency due to the presence of economies of scale.

Along these lines, aiming to compare the processes and multiple performance metrics against the references and best practices in a specific sector, benchmarking arises as a process that enables entities to develop plans and design policies on where and how to improve. WSSs are no exception, with managers, regulators, and scholars increasingly seeing benchmarking as a prized asset (see, e.g., Tourinho et al. [

16], Henriques et al. [

20], Ferreira et al. [

21]). In fact, in recent decades, benchmarking studies in WSSs have been a popular trend in the literature, with most of them using Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) as an efficiency measurement tool [

22]. Such works include, e.g., De Witte and Marques [

22] in designing performance incentives in the drinking water sector internationally, Carvalho et al. [

18] in identifying the most efficient clusters of Brazilian water companies, Pinto et al. [

23] in assessing the influence of the operational environment on the performance of Portuguese water utilities, Molinos-Senante and Maziotis [

24] in understanding the influence of exogenous and quality of service variables on the performance of water companies in England and Wales, Walker et al. [

25] in studying the economic and environmental efficiency of water companies in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland, Cetrulo et al. [

26] in analysing the performance of Brazilian water utilities, Henriques et al. [

20] in benchmarking the quality of service of wastewater operators in Portugal, lo Storto [

14] in measuring the efficiency of urban integrated water services in Italy, Maziotis et al. [

15] in understanding the impact of external costs of unplanned supply interruptions on the efficiency of Chilean water companies, Molinos-Senante et al. [

27] in evaluating trends in the performance of Chilean water companies, Mocholi-Arce et al. [

28] in assessing the performance of English and Welsh water companies, Sala-Garrido et al. [

29] in proposing a composite indicator to assess the quality of service of Chilean water companies, and Salazar-Adams [

30] in estimating the efficiency of post-reform water utilities in Mexico. A useful bibliometric analysis on the last twenty years of water utility benchmarking can be found in the work of Goh and See [

31].

Additionally, since the influence of the operational environment on the efficiency of WSSs is consensual in the literature (see, e.g., Pinto et al. [

23]), understanding the influence of factors that escape the providers’ control is a way of unbiasing performance measures [

32]. This allows for the assessment of the impact of contextual factors in the sector using a two-stage DEA approach, mainly based on regression analysis (see, e.g., Walker et al. [

25]) and hypothesis testing (see, e.g., lo Storto [

14]). Recently, Tourinho et al. [

16] summarised the most frequently used environmental variables in WSSs respecting three dimensions, despite a few conflicting results. First, in terms of organisational structure, ownership is by far the most explored in the literature (see, e.g., Cetrulo et al. [

12], Marques and Simões et al. [

13], lo Storto [

33]), given the increasing presence of private entities providing WSSs. Second, with respect to market features, customer density is the most commonly studied variable (see, e.g., Barbosa et al. [

11], Salazar-Adams [

30]) due to the possibility of providing WSSs to a higher share of the population in a more reduced area. Third, concerning operational factors, water source (see, e.g., Pinto et al. [

23]) and water losses (see, e.g., Molinos-Senante et al. [

34]) were identified as the primary influences, since surface water tends to have higher treatment costs and groundwater tends to have higher pumping costs regarding the former, and leak repair expenditures are typically high regarding the latter.

It is clear that the literature has focused on the efficiency measurement of WSSs in developed countries, even though there has been a recent increase in the number of publications in developing countries. Nonetheless, there is a lack of credible and systematic data sources on the subject, which poses one of the main obstacles to studies in this sector. Still, the particular case of Brazil emerges as an advantageous opportunity given the country’s official database on financial and operational indicators on WSSs—SNIS—which may be responsible for the greater number of studies addressing the Brazilian situation in comparison to other developing countries.

Indeed, after the seminal work of Tupper and Resende [

35] on the efficiency and regulatory issues in the Brazilian WSSs, several other publications gradually surfaced, namely, Seroa da Motta and Moreira [

9], Ferro et al. [

17], Carvalho et al. [

18], Carvalho and Sampaio [

8], Barbosa et al. [

11], Cavalcanti et al. [

36], Cetrulo et al. [

26], Ferreira et al. [

21], and Tourinho et al. [

16]. Nevertheless, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there are no studies in the literature that are focused on investigating the existence of (dis)economies of scale in the Brazilian WSSs. There are, however, a handful of publications on the subject applied to other nations (Australia [

37] and Portugal [

38]). This constitutes the knowledge gap of this paper. Thus, we propose to fill in this knowledge gap by measuring the technical and scale efficiency of WSSs in 2160 Brazilian municipalities in 2019 using a two-stage DEA approach to also assess the influence of the operational environment while considering equity in the provision of WSS. We have considered operational costs and outputs as an input, bearing in mind the efficiency of WSSs with regard to quantity and quality issues. In particular, we have considered constant returns-to-scale (CRS) and variable returns-to-scale (VRS) input-oriented envelopment DEA formulations in the first stage, and a semi-parametric truncated double bootstrap regression and non-parametric hypothesis tests in the second stage (depending on whether the contextual variables are quantitative or qualitative, respectively). The assessment of the contextual environment includes variables concerning the organisational structure, market features, and operational factors. The results show low mean efficiency scores and a tremendous potential for improvement in regard to bureaucratic processes, the reduction in operating expense (OPEX), and the increase in the

Length of the wastewater network, which is particularly significant for local-, multi-municipal/micro-regional, and state/regional policy-makers and regulators in the design and enforcement of public policy in the water and sanitation sector.

This paper is organised as follows:

Section 2 details the methodology mentioned in

Section 1;

Section 4 addresses and analyses the results of the technical and scale efficiency of Brazilian municipalities in terms of WSSs according to the description provided in

Section 3;

Section 5 discusses these, as well as proposing some key achievements, limitations, and research prospects.

2. Methods

When Farrell [

39] proposed the concept of

relative efficiency, the author understood it as the efficiency of individual decision-making units (DMUs) in comparison with one another. The most typical type of relative efficiency is

technical efficiency (TE), which estimates the ability of a DMU to use a given set of inputs to produce the maximum feasible set of outputs (known as

output-oriented TE) or to use the minimum feasible set of inputs to produce a given set of outputs (known as

input-oriented TE).

However, in practice, the production function of a DMU is unknown. For this reason, the estimation of the relative efficiency scores requires the use of approaches that can measure these based on the available data. One expample is the parametric Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA). SFA presupposes the existence of a relationship between inputs and outputs, and estimates the production function’s parameters by means of statistical techniques. It includes two error components to account for statistical noise and production inefficiency [

40]. SFA also allows for the possibility of hypothesis testing. The imposition of particular assumptions regarding the form of the frontier and the distribution of the error term constitute its disadvantages [

41]. There is also the non-parametric DEA. DEA builds a piecewise frontier using linear programming. Since it does not impose specific assumptions on functional form or distribution type, it overcomes SFA’s disadvantages. Nevertheless, its deterministic nature makes it more insensitive to digressions from the frontier, attributing them to inefficiency. Hence, DEA is more prone to statistical noise derived from data measurement errors [

40]. Ultimately, despite the apparent arbitrariness behind the choice of which method to employ, we opted for the DEA approach, since it does not assume parametric conditions over the technology of production, in line with Watkins et al. [

41].

By making use of DEA, the TE score for the DMU under assessment

was computed via the formulation proposed by Banker et al. [

42] in Model (

1) under an input orientation and assuming VRS:

where

and

denote the inputs and outputs used and produced by a DMU

j, respectively;

denotes the intensity variables that stipulate the level of similarity between an inefficient DMU and its benchmarks;

and

are the slack variables associated with inputs and outputs, respectively;

is a non-Archimedean infinitesimal; and

assumes values lower than or equal to one and denotes the factor that measures the TE of the DMU under assessment, where a value equal to one indicates a technically efficient DMU and a value lower than one indicates a technically inefficient DMU. The addition of slack variables seeks to introduce the notion of

weak efficiency, in the sense that a DMU can be technically inefficient (

), but reveal

at the optimum as at least one element of the slack vectors

or

is positive [

43]. Note that, in line with the literature, we adopted an input-oriented formulation to seek possible input reductions while maintaining the same level of service provision. For the same reason, VRS was chosen to compare municipalities with distinct scale sizes.

Moreover, the constraint given by Expression (1c) ensures the VRS assumption. When omitted, we are in a CRS situation, and Model (

1) becomes the formulation proposed by Charnes et al. [

44]. The imposition of both CRS and VRS on TE enables the computation of

scale efficiency (SE), which can be determined for a given DMU

j following:

where

and

denote the technical efficiency of DMU

j under CRS and VRS, respectively. SE assumes values lower than or equal to one, where a value equal to one indicates a DMU operating at optimal scale and a value lower than one indicates a scale-inefficient DMU. Note that

can also be referred to as

overall technical efficiency and

as

pure technical efficiency.

The presence of increasing returns-to-scale (IRS) or decreasing returns-to-scale (DRS) is responsible for the generation of scale inefficiency. Nevertheless, since the value of Expression (

2) only indicates whether a certain DMU is scale-efficient or not, information on the source of possible scale inefficiency arising from IRS or DRS must be retrieved by resorting to another approach. By replacing Expression (1c) with

in Model (

1), we can determine the TE under non-increasing returns-to-scale (NIRS). Following Coelli et al. [

45], if

, DMU

j exhibits DRS, i.e., it is operating at a larger than optimal scale; otherwise, if

, DMU

j exhibits IRS, i.e., it is operating at a suboptimal scale.

From another angle, to explore the effect that exogenous variables may have on the efficiency of the Brazilian municipalities’ WSSs, a second-stage analysis must be conducted. Several studies use either ordinary least squares or Tobit regression models, but these methods struggle with several shortcomings (see, e.g., Sala-Garrido et al. [

29]). Therefore, in line with Ablanedo-Rosas et al. [

46] and Maziotis et al. [

15], we utilised the seminal work of Simar and Wilson [

47] and their semi-parametric, truncated, double-bootstrap regression approach via Expression (

3):

where

is the vector of contextual DMU variables

j that are expected to influence its efficiency score

through the vector of parameters

that need to be estimated.

is the error term with a truncated normal distribution, with zero mean and unknown variance, and left truncated at

, such that

.

Moreover, in consonance with Sala-Garrido et al. [

29], we also used a non-parametric statistical approach by employing a hypothesis test approach, which is also in line with past research (see, e.g., Guerrini [

48]). Hence, the DMUs were grouped by considering their values on the selected exogenous variables. Then, Kruskal–Wallis

H and Mann–Whitney

U non-parametric tests were applied to test the hypotheses and assess the existence of statistically significant differences among the groups of DMUs. In particular, the null hypothesis states that

k samples are derived from the same population: if the hypothesis is true, then the distribution of the technical efficiencies is not statistically significant; otherwise, the rejection of the null hypothesis occurs at a 95% level of significance if the

p-value is equal to or less than 0.05.

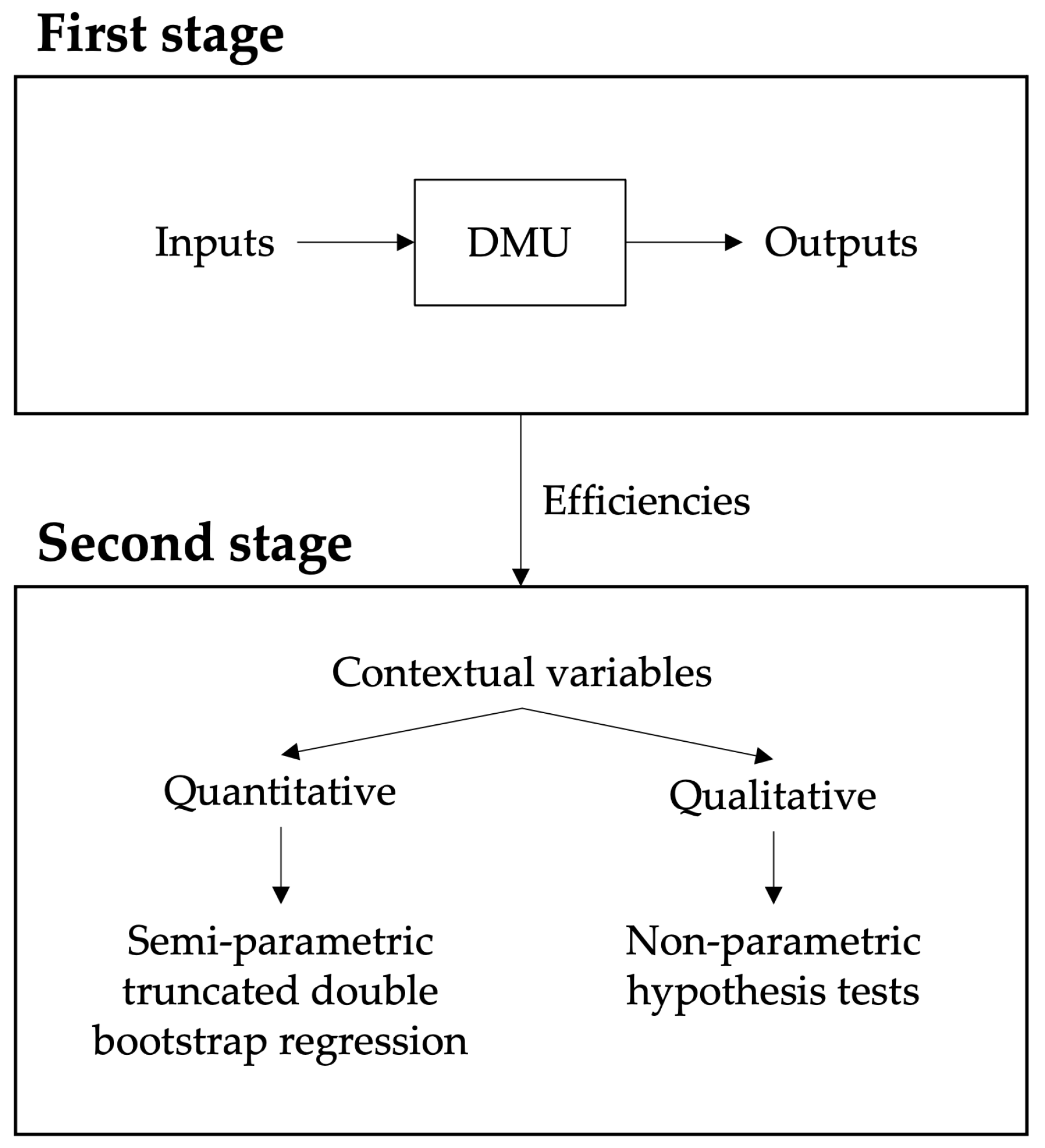

The flowchart representing our two-stage DEA approach is depicted in

Figure 1. Inputs and outputs, as well as contextual variables, will be detailed in

Section 4.

3. Case Study

First, we must select the indicators. Regarding the inputs, the literature on the subject has primarily focused on OPEX (see, e.g., Molinos-Senante et al. [

27], Maziotis et al. [

49]). Regarding the outputs, past research has paid attention to the volume of consumed water (see, e.g., Guerrini et al. [

50]) and the number of connections (see, e.g., Ananda [

51]). Following Tourinho et al. [

16], our study considered

OPEX per year as the single input, since this enables it to align with the best practices in terms of regulation; additionally, in line with the same authors, we have chosen the

Number of active water connections,

Number of active sewerage connections,

Volume of consumed water,

Volume of collected wastewater,

Volume of treated wastewater,

Length of the water supply network, and

Length of the wastewater network as outputs in an attempt to reflect all key dimensions of WSS assessment according to quality, efficiency, and sustainability perspectives.

Second, the DMU set must be built. Among the 5191 municipalities available at the SNIS water service database, which represent approximately 93% of the total number of Brazilian municipalities, and the 4226 municipalities available at the SNIS sanitation service database, which represent approximately 76% of the total number of Brazilian municipalities, we selected the 2160 municipalities that provide WSSs simultaneously, which correspond to approximately 42% of the total number of municipalities, but serve approximately 79% of the country’s population, as well as the vast majority of the share of each indicator.

Third, the main descriptive statistics of the eight indicators according to the selected DMUs are displayed in

Table 1 for the latest information available at the SNIS database—the year 2019. Note that, after conducting a Shapiro–Wilk normality test for each indicator, their respective significance value was below 0.05. This means that all indicators deviated from a normal distribution, which further justifies the non-parametric facet of our two-stage approach. Additionally, when testing for the existence of outliers in the sample, we found a mere 0.32% of instances (below the 0.74% probability of finding an outlier in a normally distributed dataset), which confirmed their trivial influence on the efficiency scores.

Fourth, the contextual variables follow the previously identified literature trends. With respect to the organisational structure, we considered

Ownership (which includes

Scope and

Juridical nature, in the sense that Brazilian WSSs, regardless of the operational scope, can be provided by direct administrations, municipal administration, mixed capital companies, public companies, private companies, or social organisations) and

Geography (which refers to

Region, since regional differences have already been identified in terms of WSS efficiency levels in Brazil). As for the market features, we considered

Customer density via the number of active water connections per length of the water supply network. Concerning operational factors, we considered

Water source through the volume of treated wastewater per volume of collected wastewater. The key descriptive statistics of these variables are shown in

Table A1 and

Table A2 in

Appendix A. Note that

Ownership and

Geography are qualitative variables and

Customer density and

Water source are quantitative variables.

5. Discussion

In the first stage of the DEA, we found a low mean overall, and pure TE scores in the 2160 Brazilian municipalities’ WSSs, sampled in 2019, consistent with the recent findings of Tourinho et al. [

16]. Furthermore, as expected, these results are due to severe scale inefficiencies, with most entities operating at a larger than optimal scale, although, interestingly, most WSSs at the multi-municipal/micro-regional level and as public companies show exactly the opposite results, i.e., are operating at a suboptimal scale. Note that the literature has already pointed towards the importance of scale-efficient WSSs [

38]. Thus, Brazilian policy-makers and regulators must focus their attention on downsizing municipalities operating at a larger than optimal scale and investing in the expansion of municipalities operating at a suboptimal scale. On the one hand, state/regional-level WSSs displayed lower mean efficiency scores than WSSs operating on a different scope (for instance, local-level WSSs were the most efficient ones), which is in line with the literature [

8,

9,

18]. Hence, policy-makers and regulators in Brazil need to decrease the complexity of the control and operation of WSSs at the state/regional level, which is evident from the higher bureaucratic processes faced by state/regional-level entities in comparison to local-level entities. On the other hand, WSSs under direct administration showed the highest mean efficiency scores (something that finds an explanation in the lack of quality of the information provided by these entities in particular, due to the fact that they do not have separate accounts and accounting and, therefore, allocate significant costs to the municipalities’ cost structure), after public companies, and the highest number of efficient DMUs alongside mixed capital companies. Again, Brazilian authorities should seek to decrease the procedural complexity behind entities with WSSs provided by municipal administration and private companies by avoiding the inclusion of multiple stakeholders in the WSS value chain. However, we found no evidence of private companies being more efficient, something that is in congruence with the literature [

9,

10,

11]. From another perspective, WSSs in the Southeast (where almost half of the country’s population and WSSs are found) evidenced the highest number of efficient DMUs and one of the highest mean efficiency scores, together with the Northeast and South entities. These results attest to the significant regional heterogeneity already mentioned in previous research [

8,

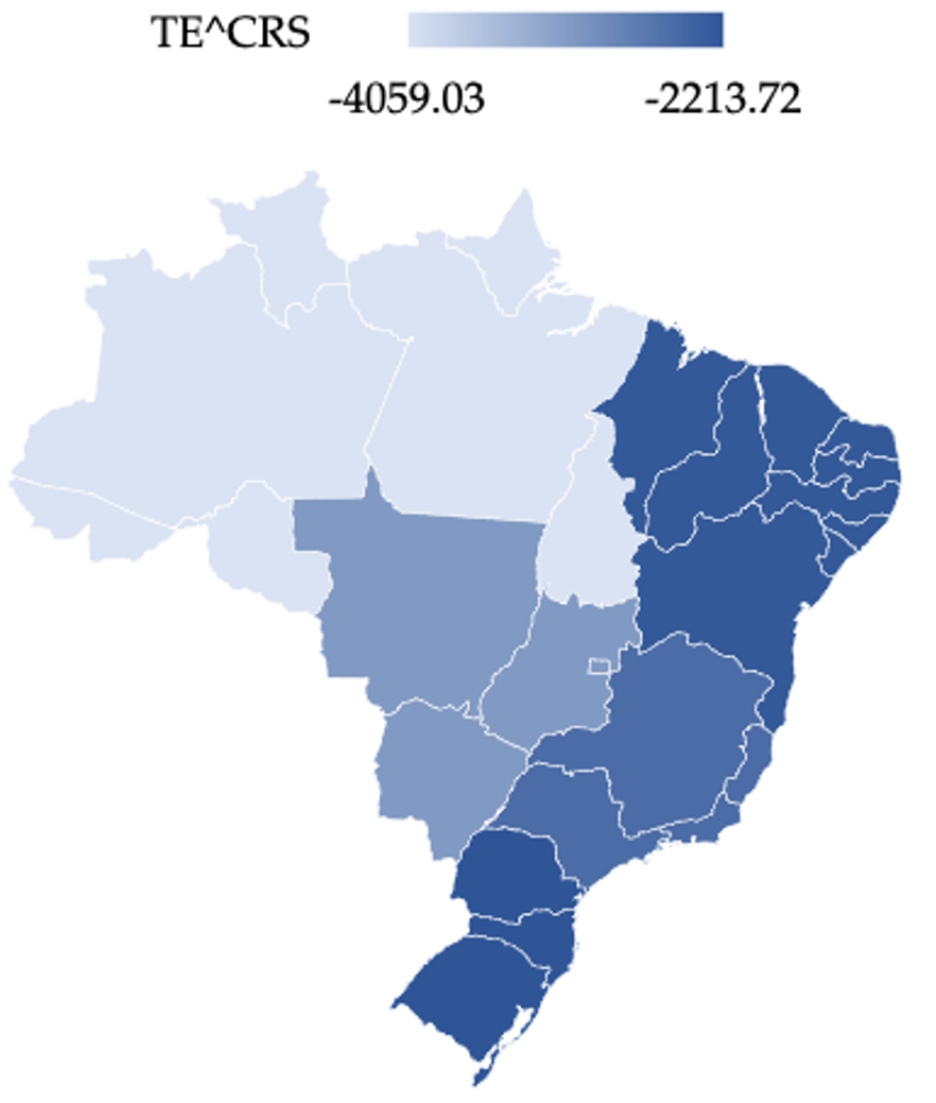

17] and the need for increased investment targeting the more underprivileged populations in the northern and inland regions.

Regarding the potential for improvement, it was clear that over 98% of the sampled entities need to significantly reduce their

OPEX, with a mean input excess of 25,051,891.87 R

$ and 11,173,670.63 R

$ (depending on whether we are assuming CRS or VRS, respectively), alongside a significant increase in the

Length of the wastewater network, with a mean output shortage of 178.26 km and 51.72 km (depending on whether we are assuming CRS or VRS, respectively). Implementing stricter expenditure control policies while investing in the expansion of the services—as was previously pointed out by Tourinho et al. [

16]—is a challenge that Brazilian policy-makers and regulators must face in the near future, for the sake of the system’s sustainability and the added value that WSSs have on the wellbeing of the Brazilian population and its socio-economic development [

21].

By conducting statistical tests in the second stage of the DEA, we were able to understand the impact of several contextual variables in the previously computed efficiencies. First, the semi-parametric, truncated double-bootstrap regression indicated that the

Water source predicted the overall and pure TE in a statistically significant way. This finding is consistent with the conclusions of Ananda [

51] and Pinto et al. [

23], since WSSs tend to be more efficient when using groundwater sources than when using surface sources (as was previously communicated by Tourinho et al. [

16]). Second, the Kruskal–Wallis

H revealed that overall and pure TE scores had statistically significant distributions in terms of the

Scope,

Juridical nature, and

Region. The consequent pairwise Mann–Whitney

U tests unveiled statistically significant differences in terms of: Local-level-State/Regional-level entities; all pairs apart from Direct administration—Public companies and Municipal administration—Mixed capital companies when assuming CRS; and Northeast-Southeast, Northeast-South, Northeast-Central-West, Southeast-South, and Southeast-Central-West entities in both assumptions, except Northeast-South entities when assuming CRS. Essentially, these results corroborate the distinct levels of heterogeneity discussed above and widely mentioned in the literature.

This study demonstrated that the Brazilian municipalities’ WSS TE goes beyond CRS and VRS assumptions, given the crucial role played by scale size. Therefore, our work showed that a benchmarking exercise comprising water supply and sanitation service perspectives, from quantity and quality standpoints, provides valuable insights to guide policy-making and regulation in a vital sector for the sustainability of the population of Brazil. Along these lines, the proposed benchmarking exercise has the potential to serve as a basis for evaluating the sustainability of water and sanitation systems in several contexts in Brazil, such as rural and urban communities, by also considering quality indicators [

52]. This could guide the country towards the achievement of SDG 6, thus counteracting its departure from the best practices, as pointed out by Pereira and Marques [

4], and individual municipalities towards achieving specific social, economic, and environmental targets. Such a composite indicator is not a novelty in the literature (see, e.g., Iribarnegaray et al. [

53] and Hashemi [

54]), but has never been considered for Brazilian reality. The study of sanitation services would be especially interesting, given its contrast with water services in the country.

On the subject of limitations, the presence of heteroscedasticity was an important concern in the second stage of the analysis as dataset was inherently prone to non-constant variance. Possible solutions for this issue include transforming the dependent variable (by taking its log, for instance) and redefining the dependent variable (by using a rate, for instance), with the authors opting for the former.

Future work concerns the evaluation of SE over time, the inclusion of additional contextual variables (especially quantitative ones), and the incorporation of weight restrictions to avoid the compensatory nature of DEA. Studying economic and allocative efficiency would also be an interesting research avenue if input and output prices are available, as well as the addition of the congestion effect to understand if there are excessive amounts of inputs causing a reduction in the outputs. The inclusion of other assessment dimensions would also enable an analysis of conflicting goals and trade-offs [

55].