Abstract

Food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations has persisted over decades despite excess food production, welfare systems, and charitable responses. This research examines the perspectives of practitioners who engage with food insecurity in Aotearoa New Zealand using a Q methodology study to synthesise and characterise three typical subjective positions. Consensus across the three positions includes the state’s responsibility for the food security of citizens, while points of contention include the role of poverty as a cause of food insecurity and the significance of a human right to food. The research contributes to research into food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations by identifying areas of consensus and contention among food insecurity practitioners, identifying the significance of children and moral failure in perceptions of food insecurity, and comparing practitioners’ perspectives to existing approaches to researching food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations.

1. Introduction

A significant minority of people living in many advanced capitalist nations suffer food insecurity. In these countries, food insecurity has negative implications for physical and mental health among adults [1,2,3,4,5,6] and children [7,8,9]. Food insecurity also impacts on the ability to participate in the social life of a community [10,11], and on healthcare requirements [12,13].

The problem of food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations has been the subject of substantial research, especially in the USA, UK, and Canada [5]. This research has tended to take one of two broad approaches [14]. The first set of these comprises critical social science approaches that foreground neoliberalism as a driver of declining economic class and for households having reduced means to access sufficient food. The second set of approaches is more policy-oriented and empirical-investigative and foregrounds the association of various factors with suffering food insecurity. Critically focused approaches argue that in advanced capitalist nations, neoliberalism has driven the rollback of social safety nets at the same time that citizens in advanced capitalist nations need them because households face falling incomes [15,16,17]. They also contend that the filling-in for states’ responsibilities to their citizens by charities is well-intentioned but insufficient, unethical, and enables continued inequity and suffering of food insecurity [18,19,20,21,22,23]. Empirically focused approaches demonstrate that suffering food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations is associated with a range of specific factors, notably household income and membership of some social groups, including gender (female) and ethnicity (non-white) [24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

Both approaches bring strengths to attempts to understand food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations—variously, a critical view of structural forces and a grasp of the breadth, variety, and entangled complexity of factors associated with occurrences of food insecurity. The two approaches are not inherently contradictory. In fact, a degree of alignment is evident in the prominence of economic factors, primarily household income, associated with food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations in empirically focused literature [28].

This research seeks to contribute to the study of food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations by discussing the perspectives of people involved in work concerning food insecurity in Aotearoa New Zealand (we use the Māori name Aotearoa as well as the English language name New Zealand in recognition of the advanced capitalist nation’s bi-cultural foundation). The intention is not to (in)validate one or other of the established research approaches to food insecurity. Instead, we want to open up the issue of food security as it exists within the specific context of Aotearoa New Zealand for (re-)examination, drawing on expertise developed by people working with food insecurity. This study is valuable for several reasons.

First, this research seeks the perspectives of people working with food insecurity across NGOs, policy, and research. The views of practitioners working with food insecurity have not been explored in academic literature. Such people are worth listening to: they have a viewpoint on the issue developed through experience and have accumulated knowledge and expertise around food insecurity. This study forms a window into perspectives on food insecurity that are significant as they inform or shape charitable, policy, and research responses to food insecurity. In addition, the mix of backgrounds, expertise, and experience across the practitioners in the study offers a solid basis to engage with views of food insecurity informed by neoliberal political rationality, which appear to be widespread in advanced capitalist nations. This inclusion adds to the mass of evidence and reports on food insecurity as a problem in those nations.

Second, Aotearoa New Zealand offers an informative case study for examining food insecurity in affluent capitalist nations and the relationship between food insecurity and neoliberalism. The country has a small population and massive agricultural production; there is plenty of food at the national level. The country also has a well-developed welfare system. However, as with many affluent capitalist nations, a significant minority of households in Aotearoa New Zealand suffer food insecurity. Records began in 1997, and the persistence of rates of food insecurity in the decades since then is alarming, as is evidence of significant and sustained sociopolitical disparities that mark the more desperate experience of particular groups [14].

Aotearoa New Zealand experienced the radical implementation of neoliberal reforms in the 1990s—the New Zealand Experiment [31]—and neoliberal political rationality has continued to influence public life since then. Neoliberal political rationality has been determinative in the presence of food insecurity in Aotearoa New Zealand. As such, “any discussion of food security, hunger, and nutritional inadequacy in New Zealand needs to be placed within the framework of growing inequality and poverty” associated with the punitive welfare cuts of 1991 and “the subsequent failure by governments to increase benefit rates” [32] to remedy the damage of the New Zealand Experiment.

Third, an examination of practitioners’ perspectives working with food insecurity has the potential for productive comparison with existing approaches to understanding food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations in the research literature. This idea will be developed in the discussion section below.

2. Materials and Methods

Practitioners engage with food insecurity in Aotearoa New Zealand across policy, charity/non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and academic arenas. We investigated the views of these well-informed practitioners using Q methodology. Q methodology is an appropriate way to contribute to research on food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations. The purpose of Q methodology is to “understand and describe shared ways of thinking about a topic” [33] (p. 219), providing tools to systematically study human subjectivity [34] (p. 1). It begins with the assumption that there are fewer ways of thinking about a given issue than there are individuals within a group of people thinking about that issue [33]. Q methodology provides a structured framework to engage with subjective viewpoints or positioning on a particular issue [35]. It applies factor analysis to identify ideal ways of thinking about an issue, perspectives or subjective positions synthesised from meaning shared between participants, captured in quantitative and qualitative data collection methods [33,36]. Q methodology does not require large numbers of participants as the analytical focus is on informed points of view.

Q methodology is useful for studying food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations because it reveals areas of consensus and controversy on a contested issue [36] and because it allows personal expression within a structured response, enabling subsequent factor analysis across responses. As it deals with subjective perspectives, Q methodology is a useful tool to investigate subjective perspectives on food insecurity and how food insecurity is understood as a problem. Subjective perspectives are significant because neoliberal political rationality is made up of people’s subjective understandings. This rationality underlies and works to justify or support small-government policy and inaction to address food insecurity with ideas of individual responsibility. It therefore seems sensible to consider subjective perspectives when seeking change in the incidence of food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations.

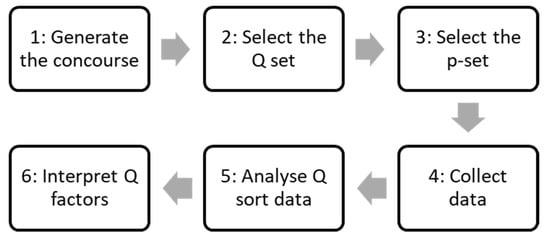

Q methodological research follows a series of steps, using several methods to build research tools and collect data. Drawing on a concise summary of the Q methodology process [37] (pp. 218–230), these will now be explained in the order indicated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The process of Q methodology research.

The first step in Q methodology research is to generate the concourse. The concourse is the set of all the possible statements that participants could express about the research topic [34] (p. 4). This is generated by a researcher who must be familiar with the topic [37]. To generate the concourse in this research, we drew on the academic literature, three semi-structured interviews, and informal conversations.

The second step in Q methodology research is to select the ‘Q set’ from the concourse (Table S1). Statements are selected to form the Q set with the intention of making a representative sample [34], one which “adequately reflects a full range of contributions to the qualitative debate” [37] (p. 220). Familiarity with the topic can allow the researcher to identify distinct aspects or themes within the concourse [37]. Doing so can help avoid overlap between statements and ensure that a range of views is represented within each theme. For this process, the Q set was parsed using a matrix of themes, an example of which can be seen in Table 1. This process of organising statements thematically aided the process of selecting a Q set that included statements that addressed major issues within each theme. It ensured that the set was not overly dominated by a particular theme, despite themes being unevenly represented in the initial body of statements generated.

Table 1.

Matrix of two themes used to characterise and parse the initial body of statements.

The third step in Q methodology research is to select the ‘p-set’. This is the group of participants in the study, chosen from a field of people who “have a defined viewpoint to express” and “whose viewpoint matters” concerning the topic of study [38] (pp. 70–71; emphasis in original). The group of participants is not randomly selected but “a structured sample” of people “theoretically relevant to the problem under consideration” [34] (p. 6). There is a practical reason for this: presenting someone unfamiliar with food insecurity as an issue with the Q set statements would not be a productive exercise. There is also a theoretical reason. The majority of research, including into peoples’ attitudes, uses R methodology. R methodology seeks to “correlate and factor traits” in participants [37] (p. 216): participants are the subject of research while features of participants, such as demographic traits, are the variables in research, and researchers probe correlations between variables and participants.

Q methodology inverts this relationship. It approaches the statements in the Q set as the subjects of research, selected as a population sample would be in R methodology. In Q methodology, people’s subjective positions are the variables [39] (p. 7). The p-set is not intended to be representative of a wider population; the population is the concourse and the representative sample the Q set. R methodology uses “by-item factor analysis” but Q methodology uses “by-person factor analysis” [35]. Subsequently, after analysis, the results of a Q study describe “a population of viewpoints and not, like in R, a population of people” [34] (p. 2).

The central importance of points of view in the methodology means that the group of participants does not need to be large, and indeed should be carefully focused. To research perceptions of food insecurity in Aotearoa New Zealand, five ways of knowing about food insecurity were identified: the experiences of food-insecure people, the research of academics, the relief work of NGOs, the work of policymakers in the area, and the range of influences on the knowledge and opinions of the public. Of groups of people who know about food insecurity in these ways, people in the first and last category were not included in the p-set for ethical and practical reasons. As data collection proceeded, difficulties with accessing right-of-centre subjectivities of those professionally familiar with food insecurity emerged. Subsequently, the criterion requiring participants to have a professional background in food insecurity was not strictly followed. This criterion seemed to be the most dispensable and was ignored to admit a single participant without affecting the other criteria: only defined and clearly articulated viewpoints with theoretical significance to the topic at hand were collected.

While not of significant importance to Q methodology, some participant demographic information may be of interest. Supplying demographic information was at the discretion of participants and on some occasions, the time generously made available to the researcher expired before it was collected. Ten participants completed a Q-sort and a short interview (n = 10). Of these, three were female, and seven were male. The average age of participants who completed the demographic survey (n = 7) was 40, with the youngest being 27 and the eldest 51. Participants identified as a variety of ethnicities, including New Zealand European (n = 3), Māori (n = 1), Samoan (n = 1), Caucasian (n = 1), and Australian-born (n = 1). All participants had completed a bachelor’s degree or equivalent (n = 6), and many had also completed a postgraduate degree or equivalent (n = 4). Participants’ household income ranges were NZD 60,001–70,000 (n = 3), NZD 70,001–100,000 (n = 2), and NZD 150,001–200,000 (n = 1).

Participants were familiar with food insecurity from an academic or research background (n = 3), as charity responders (n = 5), or as a policymaker (n = 1). Most participants’ political inclinations can be broadly described as leftist; responses were from people identifying as liberal left, classical liberal, Labour/Independent, Greens, and ‘disappointed’. Participants’ religious beliefs were described as agnostic, atheist, Christian, practicing Christian, follower of Jesus, and ‘weak’. Some general observations about commonalities between participants are that they were older, employed, highly educated, financially secure, and politically liberal.

The fourth step in Q methodology research is to collect data. Q methodology utilises both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods. In this research, the data collection procedure drew particularly on ‘Doing Q Methodological Research’ [38]. The Q sort activity with participants, which is distinctive to the methodology, was followed by a short semi-structured interview and an invitation to complete a demographic survey. Data collection was approved by the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee with application reference number 14/04 B.

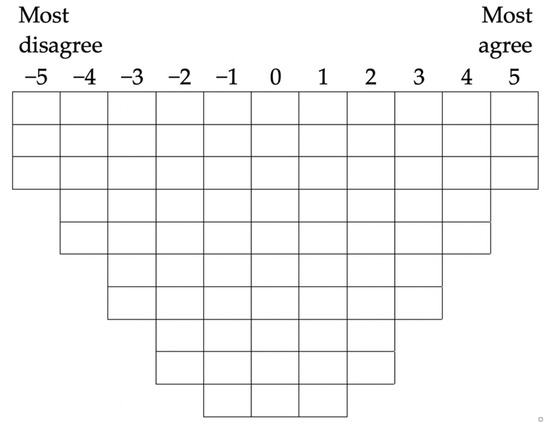

The Q sort activity seeks to capture participants’ subjective positioning on the research topic. As this is a less common method and likely to be novel to readers, the procedure followed will be described step by step. After consenting to participating in the Q sort activity and asking clarifying questions, participants received the Q set. Each statement was on a separate, randomly numbered, regularly sized card. Each card had a Velcro patch on the back to stick to a space on the Q sort grid. Participants were reminded that as the focus of the research was food insecurity in Aotearoa New Zealand, this was the context in which the Q set statements should be considered.

The Q sort activity is a framework within which participants “are asked to respond to each item and to make a specific self-referential [and subjective] judgment about it… and to do this in relation to all of the other items” [37] (p. 223, emphasis in original). To support this process by familiarising participants with the range of the Q set, participants were asked to sort the cards into three piles according to their response to each statement: generally agree, generally disagree, or feel neutral [37]. After this initial sorting, participants were asked to begin placing the statements onto the forced-distribution grid shown in Figure 2. Participants were asked to arrange the statements they felt most strongly about in the left end of the grid, drawing from the pile of statements they broadly agreed with. Participants then repeated this process with their ’neutral’ and ‘disagree’ piles. During this more nuanced sorting process, several participants reconsidered their initial treatment of one or more statements, which may have been prompted by judgement in relation to the other statements following review of the whole Q set. Participants were told to disregard the vertical position of statements and prompted to ask questions if they arose. When the participants had placed the entire Q set onto the grid, they were prompted to consider their placement of the statements and make any revisions they would like.

Figure 2.

The Q sort grid.

A short semi-structured interview was conducted after the Q sort activity was completed to participants’ satisfaction. The purpose of including this method was to assist in interpreting factors when analysing the Q sort data. Interviews lasted between 10 and 50 minutes. Participants were prompted to explain their thinking in placing the three statements in the −5 and +5 columns, were asked to reflect on how they had sorted the Q set, and whether there were particular statements they would like to discuss or explain, or to qualify placement of. Finally, participants were asked to fill out a short demographic survey as far as/if they felt comfortable.

The fifth step in Q methodology research is to analyse the Q sort data. This process aims to produce ‘factors’ representing ‘ideal types’ of perspective extracted from shared meaning between participants’ perspectives. This is distinct from the sixth step, interpreting the produced factors. Q methodology’s mix of qualitative and quantitative methods is apparent in the analysis of the Q sort data. It can be understood as a “technical, objective” procedure [34] (p. 8), but one which can be approached inductively and with input from researchers’ judgment, while always remaining a statistical exercise [38] (p. 95). The software used to analyse the Q sort data was the freeware ‘PQMethod’ [40] version 2.35. The steps involved in analysing the data are factor extraction, factor rotation, and factor estimation. These will be explained, and their process in this research described.

To explore options for factor extraction, the Q sort data—the information about where each participant placed each statement on the grid—was entered into the PQMethod software and checked for accuracy. Factor extraction is a statistical process, and there is more than one statistical method available to carry it out. Centroid factor analysis was used because it allows for decisions based on researcher judgment in the exploration of the data to direct the analysis, among other benefits. A factor is a “portion of shared meaning” between complete Q sorts [38] (p. 98), a way in which the subject positions communicated by participants through the Q sort are similar. The first decision in factor extraction is how many factors to extract. PQMethod was used to perform six centroid factor analyses of the Q sort data, extracting a number of factors from two through to seven. The six sets of results produced were investigated for viability by examining the initial schema of statistical information and through factor rotation.

A three-factor analysis was chosen for statistical and theoretical reasons. Analyses with a larger number of factors were eliminated by removing factors that did not meet the level of significant factor loading. For this research, this level was calculated to be 0.29 (or 29%) (for the relevant calculation, see [38] (p. 107)), and a factor was disregarded if it did not have at least 29% in common with two or more of the ten Q sorts. Analyses were also discarded where several of their factors had less than two Q sorts loading onto them significantly at the 0.01 level of confidence [38]. A solution with fewer factors was preferable given the relatively small size of the p-set. The size of the p-set was also a reason for choosing a three-factor solution when not all of the factors conformed to other tests recommended in the literature [38] (pp. 106–110).

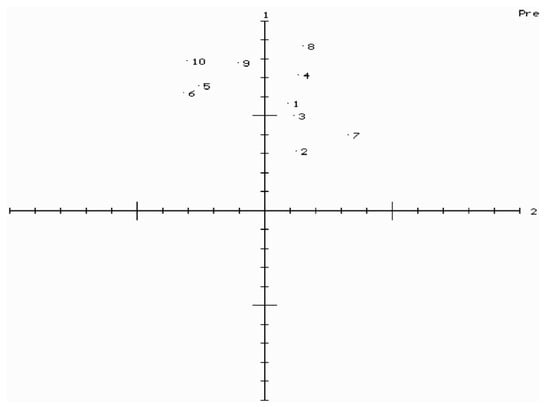

Factor rotation allows the clarification of the typified subject position that each factor represents, following factor extraction. The process uses a multi-dimensional spatial representation of the relationship between factors and Q sorts. This spatial explanation is intended to make the movement involved in factor rotation easier to grasp. Axes represent factors, and every point in this “conceptual space” has meaning, denoting a possible subjective position communicated through a Q sort [38] (p. 115). The axes range from −1 to 1, where 1 indicates a 100% overlap of meaning. The unrotated factor loadings initially give the coordinates of the Q sorts in this space—how much of the meaning of a subject position overlaps with the shared meaning represented by a factor. This initial mapping indicates the Q sorts’ relations to one another. Subject positions that disagree more or have less in common will be located further apart, while subject positions that agree more and have more in common will bunch together.

With this in mind, factor rotation involves manipulating factors (axes) in relation to the Q sorts, representing the constellation of participant viewpoints. This manipulation might appear at first to be “methodological cheating or sleight of hand” [38] (p. 129, emphasis in original). However, factor rotation “does not and cannot change the viewpoint or perspective of any Q sort,” nor the degree of overlap between Q sorts [38] (p. 129). The Q sorts’ meaning remains unchanged, as does their relationship to one another; the data remains unaltered. What moves in factor rotation is the particular perspective of the factors on the data. That is, what changes is what portion of overlapping meaning is captured by the factors, and subsequently the ability of the researcher to comprehend what is shared between the subjective positioning of particular participants.

Factor rotation aims to align factors so that their viewpoints “closely approximates” the “viewpoint of a particular group of Q sorts, or perhaps just one or two Q sorts of particular importance” [38] (p. 127). It is desirable to rotate factors because “the viewpoints provided by the extracted factors are the only means by which we, as researchers, can now access and understand our subject matter” [38] (p. 118). Following rotation, the ideal-typical subject position of the factors will more clearly reflect the subject positions represented in the Q sorts. The process of rotation produces factors which are not only meaningful, given that they are extracted from the meaning shared between participants’ subject positions, but also useful, providing insight into “distinct regularities or patterns of similarity” between participants’ responses [38] (p. 98, emphasis in original). As factor rotation is a tool engaging with meaning, though through a statistical method, “it is often worthwhile to rotate factors judgmentally [and] in keeping with theoretical, as opposed to mathematical criteria” (Brown 1980 in [38] (p. 99)).

Figure 3 shows the unrotated factor loadings of relationships between the Q sorts and Factors 1 (y-axis) and 2 (x-axis). The following may be observed in Figure 3: (1) there is a group of Q sorts—labelled 6, 5, and 10—which are clustered, indicating a similarity between these subject positions in their degree of agreement or similarity with both Factor 1 and Factor 2; (2) all other Q sorts, save 7, are similar in respect to their marginal similarity to Factor 2 but have a wide range of levels of similarity to Factor 1; and (3) Q sort 7 is not particularly unusual in its relationship to Factor 1, but is an outlier in its relation to Factor 2. It is also important to note that Figure 3 is a two-dimensional representation of three-dimensional space, the number of factors. The factors-axes are viewed from the end of another factor’s axis—in Figure 3, the positive pole of Factor 3. Factor 1 constitutes the y-axis, Factor 2 the x-axis, and Factor 3 the z-axis standing directly up from the page/screen and running its negative pole away from the reader [38].

Figure 3.

Screenshot of PQ Method displaying the Q sorts in relation to Factors 1 and 2, unrotated.

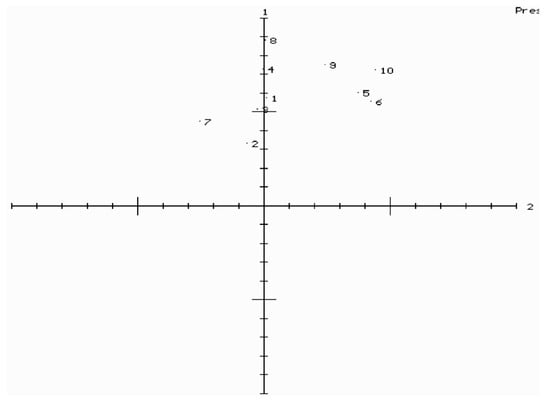

Rotation was carried out to align clusters of Q sorts with factors where possible. This is visible in Figure 4, where the relationship between Factor 2 and two clusters of Q sorts—one in a line up the y-axis and one in a group in the top-right quadrant of the graph—clarifies what those Q sorts have in common.

Figure 4.

Screenshot of PQ Method displaying the Q sorts across axes representing Factors 1 and 2 after manipulation.

Following factor rotation, the rotated factor matrix was produced to indicate how similar the subjective positions represented by the Q sorts were to the ideal-typical subject positions represented by the factors. Table 2 shows this matrix, with significant similarity indicated in bold. As noted above, this level was calculated to be a relatively low 29% similarity to a factor, due to the small p-set sample (n = 10) and the relative homogeneity of participant subject positions. Table 2 shows that Q sort 10 had a high loading on Factor 1 (85%), indicating that this Q sort was largely representative of the subject position of Factor 1. In contrast, this Q sort had little in common with Factor 2 (9%) and had nothing in common with Factor 3, directly disagreeing with 5% of that subject position.

Table 2.

The rotated factor matrix, showing the factor loadings for each Q sort, with defining Q sorts indicated in bold.

The sixth and final step in Q methodology research is to take the rotated factors and estimate the subject position that each typifies. This involved the construction of a model Q sort for each factor—a weighted average of all of the Q sorts that load significantly on a factor—using the PQ Method software. It was necessary to decide which Q sorts to include in constructing the estimate for each factor. Reasons to exclude Q sorts are their not loading significantly enough on a given factor, and Q sorts being ‘confounded’—loading significantly onto more than one factor [38] (p. 129). For reasons of scale in this research, no Q sorts that loaded significantly onto a factor were excluded from the estimation of that factor. The degree of overlap in participants’ positioning resulted in most Q sorts loading onto Factor 1. This made it impractical to exclude confounded Q sorts; such extensive exclusion would have detracted from the results, erasing important detail.

A factor estimate is made up of a score for each statement in the Q set, which illustrates the statements a factor agrees and disagrees with. Factor estimates do not allow for cross-factor comparison because not all factors are calculated with an equal number of Q sorts [38]. However, these figures can be averaged into z-scores, which are comparable and can be used to construct ‘factor arrays’—a Q set with statements arranged in “an ideal-typical representation” of the particular subject position of a factor [37] (p. 227). The data from the post-sort interviews were used to assist in characterising the factors as detailed subject positions. The depth of this data both complicated and clarified the meaning carried by the three quantitative factor arrays. Reviewing this data also suggested the heterogeneity of nuance in reasoning expressed by participants for the positions displayed in the factor arrays. This is not to say that participants who share a high loading on a factor disagree, just that agreement does not equate to the conformity of thought.

3. Results

The Q methodology study successfully revealed exciting patterns of consensus and disagreement in three ideal-typical subject positions distinctively oriented to food insecurity in Aotearoa New Zealand. These ideal types showed clustering of participants’ views around one of three potential responses and responsibilities for food insecurity. The three positions will be characterised in this section, enabling reflection on food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations in the Discussion section.

3.1. Summary of Factors

A notable consensus across all three factors was support for the responsibility of the state to support food security for its citizens. The characteristics of each factor, in terms of how each respondent understood the problem of food insecurity in Aotearoa New Zealand, are summarised here:

Factor 1:

- Food insecurity is driven by poverty, exacerbated by insufficient welfare state support.

- It is a violation of human rights and an ethical problem.

- Effective responses to food insecurity are best achieved through state action.

Factor 2:

- Food insecurity is driven by factors in individuals’ situations.

- It is a health problem and especially concerning among children.

- Effective responses to food insecurity are best achieved by addressing social issues.

Factor 3:

- Food insecurity is driven by pressures on household budgets, but not welfare state inadequacy.

- Individuals’ actions contribute to, but do not determine, food security status.

- State responses to food insecurity are adequate. Charitable responses are good but not strongly effective.

Table 3 characterises the interpretation of each of the factors across points of contention between the factors found in comparison of the three positions. Again, this interpretation draws on the interpretation of priorities in the Q sort produced by rotated factors as well as interviews with participants. Based on this characterisation, the factors will now be referred to as the ‘structural change’ position (Factor 1), ‘emotive concern’ position (Factor 2), and ‘ensuring opportunities’ position (Factor 3).

Table 3.

Summary of findings from Q methodology research.

A simple way to understand what is most important in the three positions is to look at what statements in the Q set population each holds to be the most important. Table 4 gives an overview for comparison of the statements positioned at the ends of the three factors’ Q sort distributions. The similar rankings of some statements highlight the degree of correlation between the structural change position and the other two positions.

Table 4.

Highest and lowest-ranked statements for each of the factors (+5 = most agree and −5 = most disagree).

To more succinctly describe results, comparisons between the three subject position’s treatments of particular statements will be drawn to clarify their characterisation and highlight coherence and discord. Key areas in perceptions of food insecurity in Aotearoa New Zealand will be examined: first, areas of consensus; then differences in perceptions of the problem; and finally, differences in perceptions of causes and responsibilities.

3.2. Consensus across Factors

All factors were positively correlated—they all shared some meaning or understanding of food insecurity as a problem. Several statements were the subject of a consensus between all three positions, and a selection is discussed here. The z-score and the rank of each statement are provided for comparison. The z-score shown is the distance, measured in standard deviations, from all statements’ average or centre placement so that a larger score marks a stronger feeling about a statement [38]. The ‘rank’ shown is out of the 78 statements in the Q set population.

The statement ‘Nobody in New Zealand should go hungry’ (#3) was strongly supported. This support is a strong starting point for approaching food insecurity in Aotearoa New Zealand as a problem.

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| 1.78 | 2 | 1.39 | 7 | 1.91 | 3 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

The statement ‘The state should not be expected to ensure that everybody has enough food’ (#66) was rejected, showing that all three positions see the state as having a role or responsibility to ensure citizens’ food security. What constitutes the appropriate role or actions by the state to this end are less clear-cut.

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive Concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| −1.56 | 73 | −1.8 | 76 | −1.15 | 70 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

The statement ‘Beneficiaries receive enough money to cover their costs of living’ (#18) was disagreed with, showing that all three positions view the current level of social security payments as insufficient—though the ensuring opportunities position, representing the right-of-centre perspective sought out, felt less strongly about this.

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive Concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| −1.65 | 74 | −1.34 | 71 | −0.76 | 63 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

The statement ‘Food banks are an effective way of addressing food insecurity’ (#38) was rejected.

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive Concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| −0.47 | 56 | −0.46 | 53 | −0.38 | 54 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

The statement ‘Society has failed people who use food banks’ (#5) was rejected, suggesting that there is a consensus against entirely doing away with food banks in Aotearoa New Zealand despite their being seen as an effective response to food insecurity.

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive Concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| −0.7 | 60 | −0.92 | 66 | −1.15 | 70 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

The statement ‘Free food in schools is ineffective because children attend for less than half of a year’ (#28) refers to ‘holiday hunger’ experienced by children during times when free access to meals at school is not available [41,42]. The consensus rejection of this statement may indicate an ‘any support is good’ attitude to remedying child hunger.

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive Concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| −1.36 | 70 | −1.33 | 70 | −0.76 | 63 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

The statement ‘The best way to help people struggling on a benefit is to restrict their choices’ (#25) was rejected. This paternalistic idea underlies support for such restrictions as a means of ensuring the effectiveness of some social security payments, though with little evidence [43].

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive Concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| −2.18 | 77 | −2.29 | 77 | −1.53 | 75 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

The statement ‘A priority in reducing food insecurity should be benefit levels adequate to provide people’s basic needs’ (#76) found a level of agreement, addressing views of the relationship between the welfare state and food insecurity in Aotearoa New Zealand; no position rejected the idea that benefit levels ought to ‘provide people’s basic needs’.

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive Concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| 0.66 | 22 | 0.39 | 27 | 0.38 | 34 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

3.3. Differences across Factors

Key differences between the three positions are identified and briefly examined here, with a focus on perceptions of the problem after the first two statements, which examine causes and responsibilities of the problem. Ideas about the cause(s) of, responses to, and responsibility for food insecurity are linked to the particular construction of food insecurity as a problem. What is identified as the cause of a problem informs how solutions to that problem can be approached [44].

Drawing on the emphasis on household income in the literature, the statement ‘Poverty is the primary, underlying cause of food insecurity’ (#30) was a point of strong contention between the positions. The structural adjustment position embraces the idea of the centrality of poverty to the incidence of food insecurity. The emotive concern position does not prioritise poverty particularly strongly as a cause and does not locate responsibility for food insecurity with deprived people. The ensuring opportunities position offers very little support for the idea, despite viewing household finances as significant in the occurrence of food insecurity. The support of this position for education as a response to food insecurity suggests that it views individuals as playing at least a part in causing food insecurity, despite its general rejection of individual culpability.

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive Concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| 1.63 | 4 | 0.9 | 16 | −0.76 | 63 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

The statement ‘Charities, not the state, should have ultimate responsibility for those in need’ (#72) engages with the idea of responsibility for the problem of food insecurity and has a moral dimension, indicated in the ‘should’ in this statement. The much weaker disagreement by the ensuring opportunities position indicates comfort with a more substantial role for charities in responses to food insecurity, without abandoning a commitment to the state’s ultimate responsibility.

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive Concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| −1.90 | 75 | −1.41 | 72 | −0.38 | 54 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

The statement ‘The rate of food insecurity is concerning’ (#9) demonstrated a marked decline in the strength of concern about food insecurity across the three positions. This decline suggests that the ensuring opportunities position, and to an extent also the emotive concern position, view food insecurity as ‘a concern’ as and when it is present in a fairly abstract sense, but not so much something to be concerned about in Aotearoa New Zealand.

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive Concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| 1.3 | 7 | 0.86 | 18 | 0 | 44 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

The statement ‘People have a ‘right to food’, comparable to their ‘right to free speech’ (#8) generated a similarly marked progression across the positions’ views of food insecurity as constituting a rights problem.

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive Concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| 1.69 | 3 | 1.05 | 11 | 0 | 44 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

The statement ‘Food education in schools can help to address food insecurity’ (#35) found mild but consistent support. Several statements concerning particular responses to food insecurity had this kind of response, suggesting that some specific ideas about policy interventions were neither written off nor embraced during the Q sort activity, perhaps due to a lack of relevant detail.

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive Concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| 0.18 | 36 | 0.28 | 32 | 0.76 | 24 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

The statement ‘Children deserve more help to be food secure than adults’ (#67) received split responses. The emotive concern and ensuring opportunities positions valued the idea that children’s food security is worthy of more assistance, suggesting both the universalism of the structural adjustment position and the significance of children in perceptions of food insecurity as a problem.

| Structural Adjustment | Emotive Concern | Ensuring Opportunities | |||

| 0.06 | 40 | 1.4 | 6 | 1.15 | 15 |

| z-score | rank | z-score | rank | z-score | rank |

4. Discussion

This Q methodology study in Aotearoa New Zealand contributes to the body of research into food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations. First, it has explored practitioners’ views about food insecurity in one of those nations. This adds a novel element to research in the field which has previously drawn on census and other survey data, economic data, foodbank/NGO reports, and responses from people suffering food insecurity. The value of this perspective was described in the Introduction section. At the same time, the study has expanded the application of Q methodology into the field of food insecurity (see also [45]). While our application of Q methodology revealed interesting insights that showed good content validity in relation to the wider literature, given the novelty of the methodology to this field it would be beneficial for researchers to continue to prove and report on the reliability of Q methodology through test–retest studies and assessment of reliable schematics. Second, this study has located key areas of consensus within this group of practitioners. Comparison of these with practitioners in countries, or with perceptions of food insecurity in other groups, could provide a basis for insightful comparison. Perhaps most notable is the consistent support across the three positions for the idea that the state has a responsibility for the food security of its citizens. Consensus here does not necessarily indicate consensus in the wider population, particularly given the expertise of participants and the limited size of the p-set. However, it is possible that these represent a core of ideas that are at least less contested among citizens in the neoliberalised landscape of Aotearoa New Zealand. If so, this would form a beginning from which advocacy against food insecurity might proceed.

Consensus among the factors around state responsibility aligns with the focus in critical social science research on the need for state-based responses to food insecurity to avoid reliance on insufficient and under-resourced, though well-intentioned, charity responses [18,19,20,21,22,23]. Interestingly, while this idea is closely associated with support for the human ‘right to food’ in the literature [11,18,46,47,48,49], the association is less strong in the emotive concern position and missing entirely in the ensuring opportunities position. For the emotive concern position, the lack of association of these two ideas may stem from the experiences of practitioners engaging with food insecurity. In particular, those involved with charitable responses to food insecurity may be sensitive to more or less complex situations at the household level which do not sit easily with a rights-based approach to food insecurity. Relatedly, divergence from the state responsibility–right to food association present in the critical social science literature could also arise from discomfort with the language of rights and entitlements. Participant eight explained in the post-Q sort interview that ‘rights language rankles me’—not because of the sentiment of ‘what’s best for health’ or what ‘kids deserve’, but because of the suggestion in the language of rights as ‘entitled’ individuals making demands on society.

The rejection of the idea of a ‘right to food’ by the ensuring opportunities position demonstrates that the idea of state responsibility for citizens’ food security can coexist with: a reduction in expectations of state action; a dispersal of responsibility away from the state; the incorporation of charity into the welfare state; or the notion of assistance as a privilege rather than a right. Indeed, it is possible that neoliberal ideas of individual responsibilisation are strengthened by the idea that the state ought to, and already does, offer adequate assistance to those in (genuine) need. It seems easier to conceive of households that suffer food insecurity despite such support as suffering due to their own poor choices. These are important considerations when communicating research and policy about food insecurity; the society-wide analyses in critical social science research and the universalism of a rights-based approach may need to engage with the concerns of the emotive concern position. Developing engagement with some of the detail and complexity of social problems with which food insecurity is entangled in advanced capitalist nations may be a way to further advance the strengths of critical social science research and rights-based approaches to food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations. Acknowledging the entanglement of social issues is an old and complex problem need not prompt abandoning actions to support food security.

A third contribution of this study is the identification of ideas about food insecurity and children being a key in distinguishing the emotive concern position from the structural change position. Both empirical-investigative research approaches and the emotive concern position engage with children as distinct from adults. There are temporal, ethical and emotional elements in this differential engagement. Temporally, children are young, are undergoing physical, mental, and social development, and have most of their lifetime ahead of them. Food insecurity therefore has the potential to do greater harm, and harm which lasts for a longer time, to children than it does to adults. Ethically, children do not have agency in their lives and living circumstances to the same extent that adults do, such that access to food by parents in a household directly produces access to food by children in that household. Both temporal and ethical dimensions of childhood support attention in the emotive concern position and empirical-investigative research approaches to the importance of food security for children, including the detrimental impacts of food insecurity on children.

A third dimension of childhood is the emotional potential of the figure of the child, which is linked to both temporal and ethical dimensions of childhood. The emotional potential of the figure of the child can shape politics, with the mobilisation of ideas of children’s ‘best interests’ as a potent discursive force [50]. Policy interventions focused on the food security of children can benefit from this phenomenon in the politics of resource allocation that influences policy formation and enactment. The emotive concern position highlights the potential that the figure of the child has—specifically, children suffering food insecurity—to influence the degree or intensity of concern about food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations.

A fourth contribution of this research to the study of food insecurity is the articulation of three subjective positions from practitioners which loosely resemble three well-established approaches to understanding food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations. These resemblances should not be exaggerated, but a degree of alignment suggests that the body of research into food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations is not out of step with what is viewed as significant by practitioners. The first resemblance is between critical social science research approaches and the structural change position. Both emphasise the structural nature of food insecurity as a problem in advanced capitalist nations. Both also locate the most pressing responses to the problem in large-scale structures, most significantly in remedying the deteriorated condition of social safety nets: social welfare structures in advanced capitalist nations have the potential to support food security, irrespective of the quality or quantity of employment available to a population in a given historical moment. Finally, both critical social science research approaches and the structural change position value understanding access to sufficient food as a human right.

The second resemblance is between empirical-investigative research approaches and the emotive concern position. This body of research does not ignore the significance of household incomes but does encompass a great many other compounding and complicating factors associated with food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations. In a similar way, the emotive concern position locates insufficient access to food through household budgets as a primarily economic problem but understands financial limitations in the context of other demands on household budgets. The incidence of food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations is not driven by low incomes alone, but by households with low incomes also facing difficult situations with other elements. The more household-level and detailed approach common to empirical-investigative research approaches and the emotive concern position opens up the problem of food insecurity to a far wider range of interventions than the economic remedy prioritised by critical social science analyses. From this perspective, addressing social problems is a way to support households’ access to sufficient food, even within neoliberalised welfare states; this approach may even be necessary, given that some social problems consume household financial resources. A further point of resemblance between empirical-investigative research approaches and the emotive concern position lies in understanding food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations as a health problem.

The third resemblance is between how neoliberal political rationality and the ensuring opportunities position understand food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations. These understandings overlap in rejecting the idea that the neoliberalised welfare state is inadequate to support food security. They also overlap in identifying the individuals as bearing responsibility for their own food security. Although the ensuring opportunities position described limits to this responsibility, it reflects the significance placed on individual actions as a determinant in food security status by neoliberal political rationality. The two approaches to understanding food insecurity are more closely aligned where they both locate responsibility with parents for the food security of children. Education to empower individuals to ensure their own food security and that of their children is also shared by neoliberal political rationality and the ensuring opportunities position.

The resemblances between extant approaches to the study of food insecurity in advanced capitalist nations and what practitioners engaging with food insecurity view as important are reassuring. That said, the above review of resemblances should be balanced by noting that there are divergences. One notable divergence is between the ensuring opportunities position and neoliberal political rationality, in the acceptance by the former of the state’s responsibility for the food security of its citizens. As noted above, envisioning how this responsibility is implemented seems likely to differ between the three positions, but a striking divergence remains. This may point to the complexity and variety of specific processes of neoliberalisation, as opposed to abstract neoliberal ideas [51,52]. Neoliberal political rationality is far from dead in Aotearoa New Zealand [53] following waves of neoliberalisation [51], but there may be room to build on the idea that the state’s role in ensuring opportunities for households to be food secure involves more than cutting social safety nets, austerity, or laissez-faire acceptance of society’s reliance on overwhelmed food banks ill-equipped to make good on the state’s responsibilities.

The fifth contribution of this research is the identification of moral impetus shifting between the positions. This is aligned with the location of responsibility for the problem of food insecurity in each position but extends beyond this identification. In advanced capitalist nations, where neoliberal political rationality is dominant in discursive arenas, the idea of personal moral failure is a major feature of discourse concerning food insecurity, as well as poverty and other social problems. With a view to pursuing measures to reduce the incidence of food insecurity in these arenas, considering how ideas of personal moral failure relate to food insecurity is important. The findings of this study offer some insight in this area. The structural change position looks to the state to support citizens’ food security irrespective of personal moral failure. This represents a right to food approach to addressing food insecurity, overlapping with critical social science research. The emotive concern position looks to the state to support individuals and to overcome personal moral failure through charitable institutions in communities. These are not ideas engaged with by empirical-investigative research approaches. The ensuring opportunities position looks to the state to offer support sufficient for individuals without personal moral failure. This is a point of difference from more extreme conceptions of ‘small government’ in neoliberal political rationality but aligns with neoliberal conceptions of individual responsibility.

Finally, the sixth contribution of this research is a basis for future research. There is a gap in present research into how food insecurity is understood by people who are not food insecure in advanced capitalist nations. There are exceptions, such as a study of the perceptions of food bank workers in Canada [54] and of newspaper coverage of food bank proliferation in the UK [55]. However, there is a general dearth of research to support or guide efforts to progress efforts to implement a rights-based approach to addressing food insecurity, or to otherwise find ground on which to move away from reliance by societies on insufficient charitable responses which can work to obscure the breadth or intensity of food insecurity as a problem in advanced capitalist nations. The characterisation of three subjective positions in this research can offer a basis for further research with a more general sample of the population in advanced capitalist nations.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su14010178/s1; Table S1: List of Q set statements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R. and M.M.; methodology, D.R. and M.M.; formal analysis, D.R.; investigation, D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.R.; writing—review and editing, D.R. and M.M.; visualization, D.R.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, D.R. and M.M.; funding acquisition, D.R. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a University of Otago Master’s Research Scholarship. Writing of this publication was funded by the Graduate Research Committee, University of Otago by means of the Postgraduate Publishing Bursary (Master’s).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee with application reference number 14/04 B in November 2014.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The Q methodology factor analysis results presented in this study are openly available in Zenodo.org at https://zenodo.org/record/5634116#.YcUv_1kRWUk, accessed on 30 October 2021.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Hugh Campbell in co-supervising the thesis which this research contributed to. This research would not have been possible without the generous support of its participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Elgar, F.J.; Pickett, W.; Pförtner, T.; Gariépy, G.; Gordon, D.; Georgiades, K.; Davison, C.; Hammami, N.; MacNeil, A.H.; da Silva, M.A.; et al. Relative food insecurity, mental health and wellbeing in 160 countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 268, 113556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, C.A.; Coleman-Jensen, A. Food Insecurity, Chronic Disease, and Health among Working-Age Adults. In Economic Research Report; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/84467/err-235.pdf?v=2995.2 (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Gundersen, C.; Tarasuk, V.; Cheng, J.; de Oliveira, C.; Kurdyak, P. Food insecurity status and mortality among adults in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.D. Food Insecurity and Mental Health Status: A Global Analysis of 149 Countries. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Long, M.A.; Gonçalves, L.; Stretesky, P.B.; Defeyter, M.A. Food Insecurity in Advanced Capitalist Nations: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, M.; Andrade, L.; Packull-McCormick, S.; Perlman, C.M.; Leos-Toro, C.; Kirkpatrick, S.I. Food Insecurity and Mental Health among Females in High-Income Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alaimo, K.; Olson, C.M.; Frongillo, E.A. Food insufficiency and American school-aged children’s cognitive, academic, and psychosocial development. Pediatrics 2001, 108, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyoti, D.F.; Frongillo, E.A.; Jones, J.S. Food Insecurity Affects School Children’s Academic Performance, Weight Gain, and Social Skills. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 2831–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, P.; Chung, R.; Frank, D.A. Association of Food Insecurity with Children’s Behavioral, Emotional, and Academic Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatrics 2017, 38, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowler, E.; Leather, S. Spare some change for a bite to eat? In From Primary Poverty to Social Exclusion: The Role of Nutrition and Food. Experiencing Poverty; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2000; pp. 200–218. [Google Scholar]

- Dowler, E. Food and Poverty in Britain: Rights and Responsibilities. Soc. Policy Adm. 2002, 36, 698–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Seligman, H.K.; Meigs, J.B.; Basu, S. Food insecurity, healthcare utilization, and high cost: A longitudinal cohort study. Am. J. Manag. Care 2018, 24, 399–404. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk, V.; Cheng, J.; de Oliveira, C.; Dachner, N.; Gundersen, C.; Kurdyak, P. Association between household food insecurity and annual health care costs. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2015, 187, E429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reynolds, D.; Mirosa, M.; Campbell, H. Food and vulnerability in Aotearoa/New Zealand: A review and theoretical reframing of food insecurity, income and neoliberalism. N. Z. Sociol. 2020, 35, 123–152. [Google Scholar]

- Riches, G. Food Banks and the Welfare Crisis; James Lorimer & Company: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Riches, G. (Ed.) First World Hunger: Food Security and Welfare Politics; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk, V.S.; Vogt, J. Household Food Insecurity in Ontario. Can. J. Public Health Rev. Can. Sante’e Publique 2009, 100, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppendieck, J. Sweet Charity: Emergency Food and the End of Entitlement; Viking Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Riches, G.; Silvasti, T. (Eds.) First World Hunger Revisited: Food Charity or the Right to Food? Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk, V.S. A Critical Examination of Community-Based Responses to Household Food Insecurity in Canada. Health Educ. Behav. 2001, 28, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarasuk, V.S.; Beaton, G.H. Household food insecurity and hunger among families using food banks. Can. J. Public Health Rev. Can. Sante Publique 1990, 90, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasuk, V.S.; Dachner, N. The Proliferation of Charitable Meal Programs in Toronto. Can. Public Policy Anal. Polit. 2009, 35, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasuk, V.S.; Davis, B. Responses to Food Insecurity in the Changing Canadian Welfare State. J. Nutr. Educ. 1996, 28, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broussard, N.H. What explains gender differences in food insecurity? Food Policy 2019, 83, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, K.N.; Lanumata, T.; Kruse, K.; Gorton, D. What are the determinants of food insecurity in New Zealand and does this differ for males and females? Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2010, 34, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Gregory, C.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2016. Economic Research Service; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=84972 (accessed on 19 October 2021).

- Foley, W.; Ward, P.; Carter, P.; Coveney, J.; Tsourtos, G.; Taylor, A. An ecological analysis of factors associated with food insecurity in South Australia, 2002–2007. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorton, D.; Bullen, C.R.; Mhurchu, C.N. Environmental influences on food security in high-income countries. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimaccia, E.; Naccarato, A. Food Insecurity in Europe: A Gender Perspective. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 1–19. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11205-020-02387-8 (accessed on 19 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, C.M.; Anderson, K.; Kiss, E.; Lawrence, F.C. Factors protecting against and contributing to food insecurity among rural families. Fam. Econ. Nutr. Rev. 2004, 16, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey, J. The New Zealand Experiment; Auckland Univrsity Press, Bridget Williams Books: Auckland, New Zealand, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, M. Privatizing the Right to Food: Aotearoa/New Zealand. In First World Hunger Revisited: Food Charity or the Right to Food? Riches, G., Silvasti, T., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2014; p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, M.W. Research Prioritization and the Potential Pitfall of Path Dependencies in Coral Reef Science. Minerva 2014, 52, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Exel, J.; de Graaf, G. Q Methodology: A Sneak Preview. 2005. Available online: https://qmethod.org/portfolio/van-exel-and-de-graaf-a-q-methodology-sneak-preview (accessed on 31 January 2016).

- Plummer, C. Who Cares? An Exploration, Using Q Methodology, of Young Carers’ and Professionals’ Viewpoints; Department of Educational Studies, University of Sheffield: Sheffield, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bischof, B.G. Negotiating uncertainty: Framing attitudes, prioritizing issues, and finding consensus in the coral reef environment management “crisis”. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2010, 53, 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenner, P.; Watts, S.; Worrell, M. Q Methodology. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology; Willig, C., Stainton-Rogers, W., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2007; pp. 215–239. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, S.; Stenner, P. Doing Q Methodological Research; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Webler, T.; Danielson, S.; Tuler, S. Using Q Method to Reveal Social Perspectives in Environmental Research; Social and Environmental Research Institute: Greenfield, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schmolck, P. PQMethod 2.35. 2014. Available online: http://schmolck.org/qmethod (accessed on 10 December 2014).

- Lambie-Mumford, H.; Sims, L. Feeding Hungry Children’: The Growth of Charitable Breakfast Clubs and Holiday Hunger Projects in the UK. Child. Soc. 2018, 32, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stretesky, P.B.; Defeyter, M.A.; Long, M.A.; Ritchie, L.A.; Gill, D.A. Holiday Hunger and Parental Stress: Evidence from North East England. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooler, J.A.; Hartline-Grafton, H.; DeBor, M.; Sudore, R.L.; Seligman, H.K. Food Insecurity: A Key Social Determinant of Health for Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchi, C.L. Analysing Policy: What’s the Problem Represented to Be? Pearson: Frenchs Forest, NSW, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell, M.; Croff, J.; Montgomery, D. Using Q Method to Explore Perspectives of Food Insecurity among People Living with HIV/AIDS. In SAGE Research Methods Cases; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dowler, E.A.; O’Connor, D. Rights-based approaches to addressing food poverty and food insecurity in Ireland and UK. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambie-Mumford, H. ‘Every Town Should Have One’: Emergency Food Banking in the UK. J. Soc. Policy 2013, 42, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riches, G. Hunger, food security and welfare policies: Issues and debates in First World societies. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1997, 56, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Riches, G. Canada: Abandoning the Right to Food. In First World Hunger: Food Security and Welfare Politics; Riches, G., Ed.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, B. Child politics, feminist analyses. Aust. Fem. Stud. 2008, 23, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humpage, L. Policy Change, Public Attitudes and Social Citizenship: Does Neoliberalism Matter? Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, J.; Tickell, A. Neoliberalizing Space. Antipode 2002, 34, 380–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackell, M. Taxpayer Citizenship and Neoliberal Hegemony in New Zealand. J. Political Ideol. 2013, 18, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasuk, V.S.; Eakin, J.M. Charitable food assistance as symbolic gesture: An ethnographic study of food banks in Ontario. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 1505–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, R.; Caraher, M. UK print media coverage of the food bank phenomenon: From food welfare to food charity? Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1426–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).