1. Introduction

The tourist phenomenon represents one of the most efficient segments of the world economy, characterized by its dynamics, multiple motivations, as well as the great diversity of forms of manifestation [

1]. During 2008–2018, the contribution of tourism to total GDP increased in 43 of the 70 countries that reported data. This highlights the growing importance of tourism in the global economy as well as its potential for contributing to inclusive and sustainable economic growth [

2]. Tourism also has a leading role in promoting the perception of the destination internationally [

3].

Tourism is an indicator of development and can make a significant contribution to economic growth, diversification of sociocultural activities and sustainable and territorial development if it is methodologically planned and limited to the imperative purpose of humanity in which defending and improving the quality of the environment becomes vital [

2,

4].

Territorial development is a complex phenomenon that affects the entire economic, social, political, and cultural life of a territory. Among the internal factors with an important role in prioritizing future investments in agriculture, within a region, are the following: agricultural resources; geographic position; human resources; agricultural capacity and structure; the image of the region in the world; dynamics and level of modernization reached; the level of competitiveness of important agricultural products and, last but not least, the development of tourism, as an important factor in inducing demand for domestic agricultural products [

5,

6].

The major objective of territorial development, according to Benedek [

7], is to cover local and regional human needs, the most important of which are to provide access to employment, economic growth, the formation of production networks and services strongly integrated in the context, local and regional development, and the creation of a regional environment conducive to development [

8,

9]. The territorial approach aims to make places more competitive and attractive in a national context and in a globalized environment. The territory is considered the place with its own histories and identities, where local heritage and assets are used as elements and motives for regional construction and sustainable development. It is relevant in the rural areas.

Rural areas are vital for the European Union (EU) because they cover almost 88% of the territory and account for 59% of the population [

10]. In Ireland, Slovenia and Romania, more than half of the people live in rural area.

The adoption of a code outlining the guiding principles of balanced rural development—as well as sustainable development of the agricultural sector and also of the rural area at continental level, such as the European Charter for Rural Areas (April 1996)—was based on the multifunctional and sustained development of the rural environment and the sustainable exploitation of the available natural resources, taking into account the fact that most of the food for the population of Europe, especially important raw material resources, comes from these areas [

11]. Rural areas are currently undergoing significant economic and social changes, largely driven by the liberalization of international trade, the development of communication technologies and the strengthening of rural development policies [

12,

13]. It is widely accepted that agriculture is no longer the “backbone” of the rural economy, and its contribution to GDP and employment in most rural areas is in relative decline [

14].

Most EU rural areas undergo significant economic and social changes. There is a growing awareness of the need to accompany change in rural areas by diversifying their economic base which seems to be the only answer to their socioeconomic survival [

12]. Improving the competitiveness of rural areas means supporting the quality of life of the rural community and encouraging the diversification of economic activity in rural areas [

13]. The measures found in the new EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) for the 2021–2027 timeframe highlight the establishment of a more intuitive and innovative policy, ensuring that the CAP is able to continue to support European agriculture, facilitating the creation of prosperous rural areas and ensuring production of high-quality food in the coming year [

14].

The rural environment is the repository of resources for a new beginning of new economic thinking. One of the most popular rural development strategies has, of course, been to develop rural tourism and to capitalize on its associated entrepreneurial opportunities aiming at generating money, creating jobs, and supporting the growth of retail trade [

15].

Rural tourism—based on three coordinates: space, people and products—attracts large numbers of tourists, triggered by the distinctive features of the landscape and the richness of local resources, in rural areas that constitute recreational features and ensure spiritual, environmental and cultural growth [

16]. The tourist is also preferentially polarized by the places of production that are typical for a certain area to learn about food, to understand local production systems and techniques, to discover material testimonies (old cars, buildings, etc.), to immerse in the local culture (folk art, crafts, etc.), resources that define the concept of territorial identity [

17].

Similar to other regions of Europe, rural areas in Romania have experienced a decline in agricultural activities, the restructuring of rural society and increased abandonment of agricultural land due to the aging of the rural population and to the migration of young adults to urban areas or abroad, to countries in the center or the west end of the continent [

18]. From among all of these consequences, the aging of the rural population endangers the sustainability of rural areas.

In this context, it is relevant to remind the health emergency triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, one cannot but consider its dramatic impact upon the tourism and hospitality industry. It is producing new rules and determines the adoption of innovative ways for providing and carrying out activities in tourism and hospitality. The worldwide economic damages caused by the impossibility of travel due to the pandemic are truly enormous for almost all countries, with rural destinations being affected even worse.

Despite the many restrictions and the impossibility of travel due to the pandemic situation, people are still eager to return to their previous habits. Furthermore, in the current context, tourists tend to lean towards small lodgings, in remote destinations, considering opting for self-catering services. This orientation clearly favorites rural destinations [

19].

The objective of this paper is to investigate the economic, sustainable, and social roles of tourism in the development of the rural area Mărginimea Sibiului, in Romania. This study aims at identifying the role played by the rural cultural heritage as a tool in promoting rural tourism and as a means of increasing the competitiveness and resilience of the destination, to increase tourism efficiency and to contribute to the development of more sustainable forms of economic development. In addition, the current growth of rural tourism, as well as its forms of organization, are explored to clarify a paradigm specific to territorial development. The paper continues with a section comprising the literature review dedicated to rural tourism, sustainability, and resilience. Further, the most consistent part of the article consists of a case study on Mărginimea Sibiului, which debuts with an argumentation of the chosen research methodology, which also includes the research aims of the paper. The findings of the analyses are discussed throughout the dedicated section. The final part of the paper summarizes the main conclusions, points out the limitations of the research and highlights the future development perspectives.

2. Rural Tourism as a Form of Resilience

Economic growth is one of the most well-known positive overall effects of tourism, and, particularly in rural settlements, it increases income, thus, improving the local stakeholders’ quality of life by providing diversified employment opportunities, in order to reduce poverty in rural settlements [

20]. Furthermore, tourism development also has social impacts, improves social welfare, and enhances cultural centers and local pride [

21].

The development of tourism in developing countries is seen as an economic generator capable of reducing poverty and of increasing income, achieved through the organizations’ awareness to preserve their cultural heritage and the stakeholders’ networking with the surrounding environment [

22]; in developed countries, the empowerment of the local stakeholders has been achieved by enhancing responsibility and participation in sustainable tourism development.

Rural tourism is considered a small-scale form, controlled by local people who run small family-owned businesses and strong connected by cooperation and integration in order to gain benefits for the stakeholders involved, having traditional character and determining a low impact on both nature and rural society. It is also closely linked to sustainable tourism and seen as a win–win situation for local residents, tourists and the environment [

23].

Woods [

24] defines rural tourism as “touristic activities that are focused on the consumption of rural landscapes, artefacts, cultures and experiences”. A significant importance is granted to the sensory impressions in the rural tourism experience [

25,

26], and because these are place-related [

26], they are referred to as rural sensescapes. Important links exist between developing sustainable food experiences for tourists and policies for agriculture, food production [

27], tourism, cultural and creative industries [

28,

29], especially country branding

Haven-Tang and Jones [

28], as well as Privitera et al. [

30,

31], emphasize the strong relationship between agricultural products, culinary heritage and tourism allowing the visitors to participate in the local food and drink supply chains, enhancing their involvement in the “rural experience” and their contribution to local development. It is often argued that local food, perceived as authentic and linked to local culture, works as an effective tool to sustain rural tourism and rural communities [

16,

32]. Additionally, it has been observed that rural tourism can be a catalyst for socioeconomic development and regeneration [

33], especially valuable in places where traditional agricultural activities are in decline [

34].

Rural regions with many heritage sites became more visible to visitors if accompanied by interpretative centers that offer good infrastructure and service facilities. Studies as Butler et al. (1999) [

34] emphasize the need to distinguish sustainable tourism and the development of tourism on the principles of sustainable development, while Leeuwis (2000) [

35] reconceptualizes participation for sustainable rural development towards a negotiation approach, revealing that the implication of the actors in sustainable tourism development is considered a process of learning, decision making and social learning.

Generally, rural accommodation facilities are small units, locally owned, which allow a differentiation of the rural tourism product and a personal contact with hosts, representing the key reason why people choose rural holiday [

36]. Sustainable accommodation and lodging represent an important aspect in sustainable tourism development. Hall et al. (2016) [

37] present the results of a systematic analysis of articles on attitudes, behaviors and practices of consumers related to the provision of accommodation with respect to sustainability.

The European Commission launched in 2013 the “European Tourism Indicators System” (ETIS) as an integrated tool for the sustainable development of destinations across Europe; its main goal is to provide a practical tool for destinations to manage and improve sustainable tourism at local level. This system comprises 27 core indicators and, additionally, 40 optional indicators [

38].

Agritourism “represents a sustainable on-farm connected, complementary and diversified activity for family conducted working farms with predominating agricultural activities, which are producing for the market to generate additional agricultural income” [

39]. It is considered a key factor for local development [

40,

41,

42,

43], mostly for marginal rural areas where the possibilities of developing alternative job options are restricted. Moreover, agritourism participates in maintaining the sustainability of the rural localities, considering that the depopulation phenomenon is clearly manifested by the migration of young people to urban regions and abandonment of their houses. The uniqueness of agritourism products includes specific identities, such as landscape, traditions, traditional food, art and culture, the farm life and life in nature. It is seen also as an activity that can be considered an ally of agriculture, mainly from the point of view of the conservation and protection of the rural landscape. Usually, tourists involved in agritourism are taught the way organic foods are produced and directly participate in certain processes related to cultivation or harvesting [

44]. The stakeholders’ involvement is agreed to be critical [

45,

46]; moreover, a number of studies explore sustainability imperatives from the point of view of rural communities [

47].

Aronsson [

46] outlines in his study that locals will generally accept and back-up tourism if it yields sociocultural and socioeconomic benefits and if the environment is protected. Local community participation remains vital in the process of pursuing sustainable tourism [

48]. Bramwell [

49] also revealed that the participation of destination communities is a key element for attaining sustainability through their involvement in tourism planning and governance.

Small tourism entrepreneurs have a significant importance in rural development because they contribute to the revitalization of the social and economic life of a community by generating income that can improve the environment and landscape through a higher level of general business activity [

50]. Lee and Jan [

51] indicated that managers of community-based tourism (CBT) may provide educational services and farming experiences that will increase tourists’ satisfaction and create new income sources in agricultural communities, which will promote economic sustainability.

The sustainable development in tourism is a dynamic concept, which has direct effects on competitiveness [

52], and its principles focus on three essential issues: the environment, economy, and sociocultural development. In order to generate sustainability at the destination level, a coalition of independent tourism partners and organizations, annually awarding worldwide sustainable-oriented destinations from around the globe, named Sustainable Destination Top 100 was created [

52].

Jugănaru et al. [

53] suggested a list of sustainable tourism types including ecotourism, green tourism, rural tourism, equitable tourism, and responsible tourism. Sustainability in tourism represents the future of the sector and outlines a variety of practices such as ecotourism, nature-based tourism, heritage tourism, community-based tourism, and rural tourism [

54].

Sustainable rural tourism aims to increase destination sustainability, concerning the long-term improvement of living standards, by maintaining the balance between environmental protection, the promotion of economic benefits, the establishment of social justice, and the maintenance of cultural integrity [

55].

According to Javier and Dulce [

56] (p.2), “sustainable tourism development refers to the management of all resources that meets the needs of tourists and host regions while protecting the opportunities for the future, in such a way that economic, social, and aesthetic needs can be fulfilled while maintaining cultural integrity, essential ecological processes, biological diversity and life support systems”. Another study [

57] describes three principles of sustainable tourism, namely the quality experience for visitors, improvement of the quality of life of the host community, continuity of natural resources and equilibrium between the needs of hosts and of the environment. Further, other researchers [

57] deal with sustainable tourism in terms of economic, environmental and sociocultural principles as the “triple bottom line”. Some scholars carried out studies related to aspects such as tourism environmental carrying capacity [

58], tourism environmental quality assessment [

59], tourist ecological footprint [

60], and satisfaction in sustainable tourism [

61].

3. Rural Tourism in Romania and the Case of Mărginimea Sibiului: An Overview

3.1. Rural Tourism in Romania

In Romania, rural tourism has been practiced sporadically since the 1940s [

13,

15]. For the organization and promotion of tourist villages in the area between the Carpathians, the Danube and the Black Sea, the Research Center for the Promotion of International Tourism (RCPIT) conducted a study in 1972, which led to the identification and selection from among all the ethnographic areas of the country, of a number of 118 rural localities (further considered as tourist villages). In 1973, only 13 localities were declared experimentally tourist villages (out of which two villages from the microregion Mărginimea Sibiului—Rășinari and Sibiel). Of these localities, nominated as tourist villages, only two rural settlements were truly operational for tourism (Sibiel and Lerești, Argeș County), along with the framework for organizing, operating and guiding tourism and promoting tourism in these localities [

15].

The promotion in the 1970s by the Carpathian National Tourism Office of the tourist program “Wedding in the Carpathians” in the villages of Bogdan Voda (Maramureș County), Sibiel (Sibiu County) and Lerești (Arges County) was a favorable premise for the development of rural tourism in regions with a more accentuated ruralism (Maramureș Depression, Mărginimea Sibiului or Argeș Subcarpathians).

After 1990, the interest for the affirmation and development of tourism in rural areas was revived with the establishment of several associative forms: Opération Villages Roumains Association, Romanian Federation for Mountain Development, National Agency for Rural, Ecological and Cultural Tourism, founded in 1994 and member of the Federation European Agency for Rural Tourism (EUROGÎTES), especially the Romanian Agency for Agritourism (1995) [

11].

At the end of the 1990s, David Turnock made a pertinent radiograph of Romanian rural tourism where 45 tourist villages are mentioned (especially viable tourist villages from 1973, villages with registered tourist activity in 1992; pilot tourist villages proposed by Opération Villages Roumains in 1995, and the villages with more than 10 tourist reception structures with accommodation functions, included in the first PHARE Program for rural tourism in Romania, at the level of 1996, a program that aimed at ensuring the mechanisms for an interconnected computer system at the European Central EUROGÎTES reservation systems) [

62]. The main regions, counties and localities with intense tourist activity are located in the Carpathian, sub-Carpathian areas, the Hilly Depression of Transylvania, the Suceava Plateau, the Mehedinți Plateau and in the Danube Delta.

Previous studies [

63] show that Sibiu County attracts a large flow of tourists through the localities belonging to the five microregions with a pronounced multicultural character (Mărginimea Sibiului, Țara Secașelor, Țara Oltului, Valea Hârtibaciului and Valea Târnavelor), to which is added the cultural personality of the city of Sibiu [

64]. The older antecedents of rural tourism in Mărginimea Sibiului are complemented by other significant events, which led to a renewed interest in rural tourism as a factor of socioeconomic development and regeneration of rural areas, such as designation of Sibiu as European Cultural Capital in 2007, next to the capital of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg; the recognition in 2015 of the Mărginimea Sibiului microregion as a European Destination of Excellence for Tourism and Gastronomy; the designation of Sibiu County in 2019 as European Gastronomic Region along with the South Greece region (Greece); and, last but not least, the most recent statute of Sibiu County, that of Europe’s Hiking Capital, as the host destination of Eurorando.

3.2. Research Methodology

Due to the fact that this paper focuses on establishing whether the destination under scrutiny has managed to develop a successful form of rural tourism and what determines its success, the case study method has been identified as the most appropriate research method for this purpose. Therefore, the authors have opted to employ the case study method for a better understanding of the development of sustainable tourism and sustainable rural lodgings in Mărginimea Sibiului.

The authors have opted to employ the case study as qualitative inquiry method [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69], bearing in mind that qualitative studies represent a large area and can consist of exploratory, explanatory, interpretive, or descriptive purposes. They can be carried out as narrative research [

67] responding to the researchers’ needs to illuminate understanding of complex phenomena [

65,

70,

71] and situations. The case study method has been considered appropriate for the purpose of the current analysis due to the fact that it is exploratory and explanatory in nature and it enables the comprehension of real life contexts, primarily providing answers to research questions such as

how? and

why? and sometimes, also,

what? [

65,

66,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74]. Furthermore, Stake [

75] emphasizes that the focus of the researcher falls on what is studied (the case) rather than how it is studied (the method).

The authors aim at establishing and evaluating the context of rural tourism development in Mărginimea Sibiului and the perspectives of its sustainable development, relying on induction and deduction, inter-related processes that have had a significant contribution to the assessment, analysis, interpretation, and understanding of the past and current state of the hospitality services provided in the investigated area. The authors considered the past and present-day situation as registered by the Romanian Ministry of Tourism (MT), especially by the National Authority for Tourism (NAT) (governmental operational structure subordinated to various ministers over the timeframe of the study); throughout the paper, the institution is going to be referred to as MT/ NAT. The second important source of secondary data was the National Institute of Statistics, based on which data regarding the destination’s demographics, socioeconomic development and tourism supply-side statistical data were collected and processed with the purpose of assessing the destination’s sustainable development. In order to achieve this goal, the authors formulated several research questions. Thus, the paper aims at the following:

establishing whether tourism contributes to the wellbeing of the destination’s inhabitants;

establishing how the destination’s supply has developed and how it performs compared to the county of Sibiu to which it belongs;

identifying the type of ownership and operation of the hospitality services in the area;

assessing the dimension of women-entrepreneurship.

This is the first stage of a series of studies that are dedicated to the same destination. These shall further address both the demand and the supply sides. Thus, the next research stage will include in-depth interviews with the entrepreneur-managers of the providers of hospitality services (mainly lodging and foodservices) in the area and interviews with the destination’s stakeholders, aiming at comprehending what triggers them to invest and to operate businesses providing lodging and foodservices as well as a better understanding of how they perceive the future of the destination, especially how they adapt to the new situation. Given the difficulties encountered by the sector at this moment, generated by the pandemic situation, it was decided not to postpone the interviews. Moreover, the future research directions shall address the demand-side as well, having in mind the fact that the destination features many relatively small accommodation facilities that, in the new COVID-19 context, seem to be more attractive for both domestic and international tourists.

3.3. The Case of Mărginimea Sibiului

In this study, the ethnographic area, Mărginimea Sibiului, from Sibiu County of Transylvania (located in the Center Development Region of Romania) represents the ‘case’ selected for this research that proposes to highlight the sustainable development of the destination and to analyze it from the supply-side perspective. The case study has been elaborated using desk research methods and employing national statistics and databases of lodging, food and travel services provided by The National Authority for Tourism under the coordination of the ministry in charge of tourism activities or by the Ministry of Tourism. The selection of these sources of data was determined by the fact that the National Statistics Institute does not collect data from lodgings with less than 10 beds; therefore, small lodgings are missing from the national statistics, while they are typical for Romania’s rural destination and have become extremely attractive in the current COVID-19 context. The first available database was published by the National Authority for Tourism in 2005, covering lodgings established between 2000 and 2005. Further, it has been established to work with the databases of 2010, 2015, 2016, 2020 and 2021. Lodging and foodservices have been analyzed both at the level of the microdestination and in terms of their contribution to the lodging supply of Sibiu County. Travel services have been cached in all available databases.

Mărginimea Sibiului is a unique ethnographic area, located in Southern Transylvania, in Sibiu County, Central Region (

Figure 1). It belongs to the contact area between the hilly depression of Transylvania and the Cindrel Mountains, in the longitudinal submontane depression Sibiu-Săliște, which has a sedimentary basin located in the immediate vicinity of the mountain [

63].

To the north and south, the depression is bounded by high hills of 450–500 m and mountain ranges that rise to 900–980 m. Between these altitudes, the combination of natural ecosystems—forests, agriculture, and human cultural system—forms a unique relationship of perfect integration and of major importance for the region’s sustainable development.

From a climatic point of view, tourist activity is possible throughout the entire year. The average annual temperatures are of 8–9 °C, with 18–19 °C during the summer season, and of −4, −5 °C in the winter. The average annual rainfall is of 650–700 mm, with maximum values in June and February [

76]. During the winter there are temperature reversals in the depression, while in the spring the foehn manifestations of the Great Wind from the Cindrel Mountains are registered [

76]. The conditions offered by the relief and the cool climate have imprinted the soil cover with particularities that make them usable by grazing for shepherding or for various agricultural crops (cereals, technical plants, fruit growing).

The good sheltering conditions of the mountain with its wood and grazing resources, as well as the agricultural space in the depression, have contributed to the constant increase in the number of inhabitants and the formation of viable human settlements. Of these, 18 localities are comprised by the Mărginimea Sibiului microregion: Boiţa, Sadu, Râu Sadului, Tălmaciu, Tălmăcel, Răşinari, Poplaca, Gura Râului, Orlat, Fântânele, Sibiel, Vale, Sălişte, Galeş, Tilişca, Rod, Poiana Sibiului, and Jina [

63]. These localities belong to 12 administrative territorial units (ATUs), of which two are towns (Săliște and Tălmaciu) and the remaining 10 are communes. Săliște comprises three of the villages: Fântânele, Sibiel, and Vale, while Tălmăcel belongs to Tălmaciu town [

77]. The localities have developed a mixed economy, based on agriculture, zootechnics, and traditional crafts, with a special weight on shepherding. Most of the villages in the area have kept strong spiritual and ethno-folkloric traditions, continuing to stay alive as they depended on each other, according to Cristian Cismaru, co-founder of My Transylvania Association [

78]. Crafts inherited from ancestral times are still practiced successfully today. Since ancient times, these populations of shepherds have been and still are master artisans in wool and leather processing.

The gastronomy of the Mărginimea Sibiului area is widely appreciated and recognized, due to the traditional agricultural products and through the Saxon or Hungarian influences in the Romanian cuisine. The gastronomic profile is shaped by ancestral practices such as the large and small transhumance of sheep herds; old traditions in the production of

telemea (a fresh, feta-type cheese), bellows cheese (a hard, salty and kneaded cheese kept in the stomach/skin of sheep), kneaded cheese or

urdă, and the cottage cheese, too; the presence of the bread oven and the cultivation of vegetables and herbs in the traditional household; food preservation in community spaces; the cultural interaction of Romanians, Saxons, Hungarians, Armenians and the more recent influences of European or Asian cuisines [

63]. Like in other Transylvanian spaces, the Gypsies also contributed to the development of multiculturalism in Mărginimea Sibiului [

79]. Therefore, the anthropic tourist heritage also has an important intangible component; its potential is beginning to be explored.

Mărginimea Sibiului provides the landmarks necessary for community definition, but also for stimulating energies and initiatives capable of contributing to the strengthening and affirmation of local identity in a multicultural Europe and in an increasingly globalized society.

Over time, Mărginimea Sibiului has become an important destination in Romanian rural tourism, developing many agritourist and rural tourist boarding houses and where the typical peasant atmosphere is preserved, the local traditions and customs are kept intact, and where the hospitality of its inhabitants also increases the attractiveness for these places.

3.3.1. Economic Development and Wellbeing in Mărginimea Sibiului

Not in line with the national decreasing trend of the population, over the nearly past three decades, Mărginimea Sibiului has had a relatively stable population, accounting for, on average, 8.94% of the county’s total population, but it has not followed the slightly increasing demographic trend of Sibiu County. While in 1992 the total population of this microregion gathered 42,396 persons, the number slightly diminished to 41,341 people, dropping by 2.5%, while the county’s overall population increased by 2.3%. Most localities lost a part of their population, except for four communes: Gura Râului, Orlat, Poplaca, and Sadu, which gained in terms of inhabitants (

Figure 2a).

From the point of view of gender distribution (

Figure 2b), the population of Mărginimea Sibiului is practically equally split, with a slightly higher presence of women (+0.58% in average, over the entire time span). Furthermore, the overall trend reveals an aging population for the investigated region (

Figure 2c), with a higher life expectancy among women (

Figure 2d). One ought to notice that over the past few recent years, younger generations tend to orient towards their home destination, but this trend has not yet been adopted by the generation of active adults.

In the current context of the COVID-19 pandemic situation, it becomes obvious that an analysis of the evolution of employment and unemployment rates at the county level and in Mărginimea Sibiului is necessary. With less than 15% of the region’s population employed (full- and/or part-time), while the county-level percentage is double, the destination’s sustainability becomes questionable (

Figure 3a). Unemployment can and should be regarded in correlation with the increasing number of young people who opt to stay in their home region. Over the entire timeframe, the average unemployment rates registered in Mărginimea Sibiului (with Jina excluded due to its very high unemployment rates, in average of 7.3%) have been very close to the ones at the county level. In fact, the overall unemployment rates of the microregion have been and continue to be lower than those of Sibiu County (

Figure 3b). Perhaps, a logical explanation can be provided by the intense tourism activity in the area. Regarding the situation of the employed and unemployed persons in tourism and hospitality services due to the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, Mr. Roșu, the public manager of the Sibiu County Agency for Employment, estimated that more than 40% of the employees in businesses that provide tourism and hospitality services are seasonal workers (mainly university students and high-school pupils) who do not have any permanent/long-term contracts; thus, due to their flexible relation with their employers, they would return to their job positions once tourism activities restarted [

81]. A monthly analysis of the number of unemployed persons in Mărginimea Sibiului reveals that there is no seasonality influence, with the figures remaining constant both in the case of females and males, following the trend of Sibiu County; in fact, during the summer there are slight decreases in terms of numbers of employed persons (

Figure 3c).

A positive aspect worth highlighting is the fact that the microregion Mărginimea Sibiului seems to manage to retain its population to a much higher degree compared to other destinations from Sibiu County, performing better than Saxon destinations, wherefrom many persons have migrated internationally over the past more than 30 years (

Figure 3d).

3.3.2. Mărginimea Sibiului: An Analysis as Tourist Destination

For a better understanding of the context of rural tourism development in Mărginimea Sibiului, both the demand and the supply sides will be investigated. Furthermore, sustainability issues will be addressed.

As a rural tourism destination, Mărginimea Sibiului has known a quick development somewhat later than other Romanian rural destinations (Rucăr-Bran corridor, Bucovina and Maramureș); thus, the first agritourist and rural guest houses were open here only in 2001, according to NIS data. In terms of numbers of accommodation units, Mărginimea Sibiului has registered an overall growth, following the trend of Sibiu County, with a decrease between 2011 and 2014, perhaps due to the economic crisis of 2008–2010. While in the early years after the fall of communism (1990–1996), Mărginimea Sibiului accounted for less than 15% of the lodgings in Sibiu County, beginning with 1997, and until 2004, Mărginimea Sibiului provided on average nearly 45% of the accommodation units in Sibiu County, to later drop to approximately 33% in average for the 2005–2010, and to eventually stabilize around a quarter of the total available units between 2011 and 2020 (

Figure 4a). In terms of types of units, it is obvious that in Mărginimea Sibiului, the supply of lodging services is mainly ensured by agritourist boarding houses and by some rural and urban guest houses. Unlike in other very popular and successful rural destinations, in both Sibiu County and Mărginimea Sibiului, according to NIS data (2021) the development of agritourist boarding houses and of urban and rural guesthouses only began in 2001. The rural tourism profile of the destination is clear. While at the beginning (in 2001) Mărginimea Sibiului concentrated over 75% of the lodgings in Sibiu County, indicating the fact that the microregion was among the initiators of rural tourism in the area, over the years, other destinations also developed and today it only accounts for a third of the county’s supply (

Figure 4b). The orientation of the locals towards developing facilities for rural and agritourism led to the emergence of a stable supply covering constantly around 15% of the county’s available bed-places in all lodgings and initially (in 2001) of nearly 60% of the beds in agritourist boarding houses and rural and urban guesthouses, to account nowadays for a little more than a quarter of these structures’ capacity (

Figure 4c).

As expected, the functioning lodging capacity of Mărginimea Sibiului is dominated by agritourist boarding houses and rural and urban guesthouses. In terms of available functioning capacity, it accounts for less than 25% of the county’s available beds in boarding houses and for a little more than 10% of the total functioning bed-places in the case of all lodgings from Sibiu County. A low seasonality can be observed, but overall, the provided available capacity is relatively stable throughout the entire year both for all types of lodgings and for boarding houses over the entire analyzed timeframe (2010–2021) (

Figure 4d,e).

For a better assessment of sustainability issues, an in-depth analysis of the accommodation services is needed. Thus, relying on the collection of Authorized Lodgings provided by de Ministry of Tourism/National Authority for Tourism, the authors draw several concluding remarks concerning the supply side. Given the large volume of data, it has been decided to take the first available database (for 2000–2005) and to cross it with the ones published in 2010, 2015, 2016, 2020, and 2021.

The reality of the lodging market reveals a significant number of small structures that are not taken into consideration by the National Institute of Statistic, which collects data only from lodgings with at least 10 beds. Thus, a very important market sector is completely ignored both in terms of assessing its size and in what regards tourist activity. Moreover, especially today, when both hosts and tourists face the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, small structures are very attractive and prove to be preferred by tourists. A synthetic situation of the development of lodging facilities in Sibiu County and in Mărginimea Sibiului is presented in

Table 1, above, highlighting the fact that the investigated destination concentrates a large quota of the county’s specific rural tourism supply (agritourist boarding houses, rural and urban (from small towns) guesthouses, and more recently of villas and rooms to let). Despite the worrisome times, investments in hospitality services continue to grow, entrepreneurs proving their positive thinking capacity. Furthermore, their attitude can be associated with their understanding of the great potential of community-based tourism development [

82,

83] and of the attractiveness of small lodgings in this context as well.

The same procedure has been adopted for foodservices; the first available database, in this case, is that from 2010. The last year has been selected in order to evaluate the impact of the first year of the COVID-19 pandemics upon the activity of hospitality players in Mărginimea Sibiului.

As anticipated, the supply of accommodation services from Mărginimea Sibiului is clearly dominated by agritourist boarding houses cumulated with rural and urban (from the small towns included in the microregion) guesthouses. Overall, the development of lodging services in the area indicates an orientation of the owners and/or managers towards relatively small structures that capitalize on the destination’s potential. The more recent development of chalets, villas and rooms to let and/or apartments is consistent with the destination’s profile but also reveals a lack of understanding, among investors, that guesthouses have proven to be the region’s key to success (

Figure 5a). The growth trend has been registered both in terms of rooms and of available beds, knowing an alert pace (

Figure 5b). A significant change in terms of size can be observed over the first 10 years of activity. This indicates a constantly growing demand and, therefore, a higher interest towards hospitality business development among the local population. No other significant size changes have been registered after 2015 (

Figure 5b,c).

Concerning the provided accommodation services’ quality and level of comfort, one ought to notice the significant shift from a predominantly low ranking (of one and, mainly, two stars and daisies, with very few units ranked at three stars/daisies), to a supply consisting of mainly three-star/daisies units, followed by two-star ones but also with developing four- and five-star segments (

Figure 5d). The providers of accommodation services undertook changes in their facilities’ structures as well. While the supply was initially dominated by two-room structures—followed by units with three or four rooms, respectively, even one room—beginning with 2010 they began to extend their properties. Still, even today, the offer of lodging services in Mărginimea Sibiului is dominated by relatively small units, being equally split between facilities with one to five rooms and 6 to 10 rooms, which can still provide intimacy and a nice interaction with the host, not losing in terms of hospitality spirit (

Figure 5e).

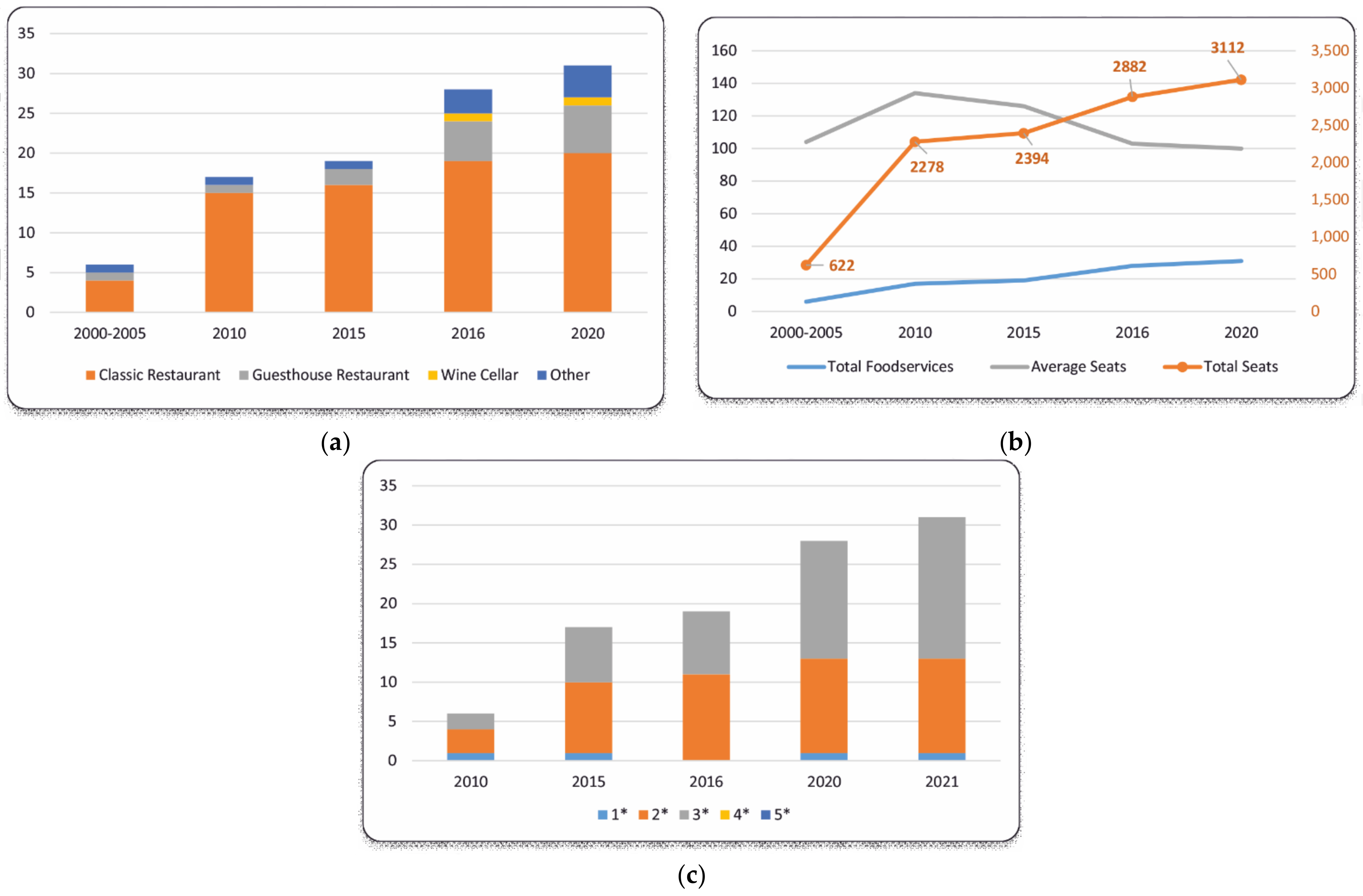

Regarding the foodservices provided in the investigated microregion, one can easily notice several aspects. While in the case of accommodation services entrepreneurs seem to have understood that their decision of investing in specific facilities (agritourist boarding houses and rural and urban guesthouses) has contributed to the destination’s success, they seem to have failed to assess the potential of providing foodservices through specialized restaurants and through locally specific restaurants (

Figure 6a). Their option to open almost exclusively relatively large classic restaurants instead of orienting towards smaller scale but diversified units indicates that they rather count on the local population, trying to capitalize on the locals’ needs to also organize large events (such as weddings, baptisms and other private or public events), failing to understand that today’s tourists are extremely attracted by gastronomic experiences (

Figure 6b). A discrete but very slow diversification of the provided foodservices seems to take place. The presence of coffee-bars and of a wine cellars suggests the beginnings of change, but the destination must continue to work in this direction. Furthermore, an improvement of the provided services’ quality is also needed because the domination of two-star structures is not satisfactory for a Gastronomic Destination of Europe (

Figure 6c).

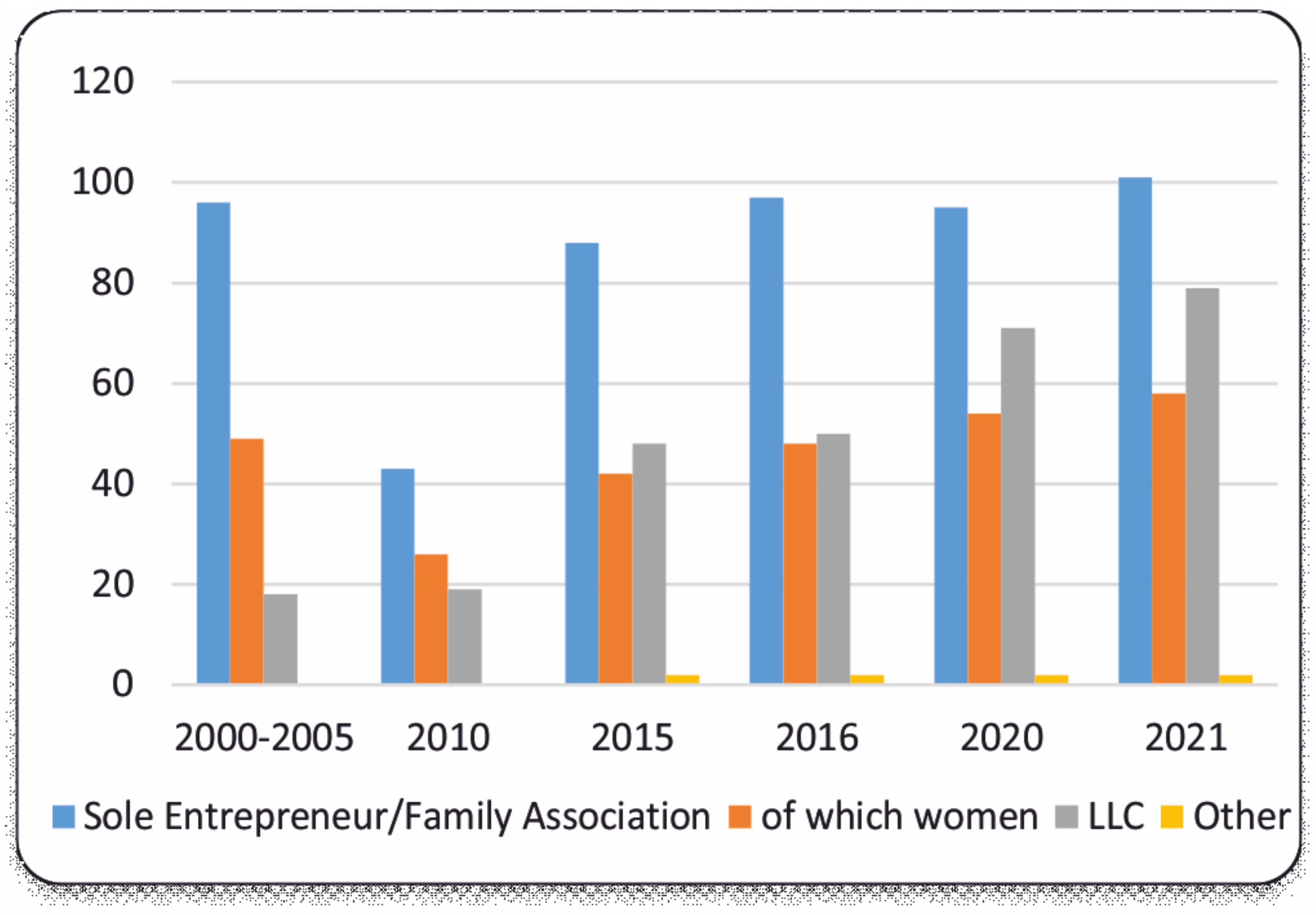

As expected, the large majority of the enterprises are family businesses (

Figure 7). A pleasant surprise was to learn that more than half of the individual entrepreneurs are women. Moreover, when analyzing the units’ names, the quota of businesses operated by women increases to more than two thirds. The same is valid for foodservice units, too. In fact, most of these ones are actually associated to lodging services. There are very few independent or self-established restaurants in the area. Another positive aspect is that over the analyzed time span, more than two thirds of the lodgings open between 2000 and 2005 continue to function today, most of them being operated by their initial owners. Most of those that have disappeared have done so before 2010. Furthermore, only six of the lodgings established in 2010 seized to function.

Another positive aspect is the fact that the development of both lodgings and foodservices has meant not only a growth in terms of numbers and available places but also a spread-out on the destination’s territory. Thus, today, 16 of the 18 localities comprised by Mărginimea Sibiului provide accommodation services (

Figure 8a), but only eight of these localities can also serve their visitors with food (

Figure 8b). It is clear that from an investor’s point of view, there is space for capitalizing on the destination’s gastronomic heritage.

4. Conclusions

The study outlines Mărginimea Sibiului as a distinct tourism destination in Romania in what regards rural tourism and agritourism as components of sustainable tourism in this region. The diversity of tourism potential given by the gastronomy and cultural traditions in this area emphasize the destination’s uniqueness and the tourist identity that has been shaped over time, hence being also known for its natural resources. The endowment of territory with many accommodation facilities ascertains the attractiveness of the region and the increasing number of domestic and foreign tourists.

The research limits must be outlined as deriving from the fact that the present paper does not benefit from the increased added-value of field research and of interviews with the destination’s stakeholders, especially of a quantitative research of the demand-side. As the authors have explained, these shortages are going to be compensated in the coming papers that will address the missing aspects based on the findings of the present paper.

The analysis of the economic development of the destination places Mărginimea Sibiului in a relatively good position, with a stable population that is equally divided between gender. The trend reveals a somewhat aging population but also a good presence of youth. Still, at the same time, a diminishing tendency among young active adults is visible. Sustainable development seems to be challenged by the low quota of the (full- or part-time) employed persons, corroborated with the migration trend of the young generations. On the other hand, unemployment is at normal levels, perhaps due to the intense tourism activity in the area. Although present, migration from the destination’s communities is not as high as in the case of Sibiu county.

The tourist destination has developed a bit later than other important Romanian destinations (Rucăr-Bran corridor, Bucovina and Maramureș). Initially it was Sibiu county’s most significant contributor in terms of lodging services (accounting for nearly 45% of the lodgings), while today it provides a quarter of the total numerical supply. With more than two thirds of the initially established lodgings in the early 2000 s continuing to function today, these facilities have proven to be sustainable and attractive businesses, contributing to the locals’ employment and wellbeing. Another fact worth mentioning is the consistency in terms of lodging facilities’ development and destination profile. Thus, the destination’s supply is clearly dominated by agritourist boarding houses and rural guesthouses, which account for a quarter of Sibiu county’s total bed-places-offer and of only a tenth of its functioning capacity. The latter aspect can be regarded as a threat for the destination’s sustainable development, but, at the same time, it should be regarded as a clear sign that a diversification of leisure services is needed, which would eventually provide more business opportunities because seasonality does not seem to negatively affect the destination. The analyses of the lodging supply revealed that the authorized facilities (not entirely caught in the national statistics) comprise a significant quota of small structures, which are in fact gaining popularity in today’s epidemiologic context. Furthermore, these structures are attractive for entrepreneurs, who, despite the pandemic situation, continue to establish and open new facilities. Overall, the evolution of the lodging services in the area points towards the preference of the owners and/or managers for relatively small structures that truly capitalize on the destination’s potential, like agritourist guesthouses and rural boarding houses, with improved rankings. There are some exceptions, namely the cases of some investors who do not seem to understand that diversification is not needed in the supply of lodging services—agritourism and rural tourism specific facilities being the winning card—but in that of the supply of food and leisure services.

From the point of view of the hospitality services provided in the area, the main findings indicate an overall growth of small lodgings and the improvement of the services they provide by upgrading the lodgings to superior ranking levels. While the beginnings of agritourism and rural tourism in the destination are associated with timid initiatives, ranked low, the 2010 database comprises more than three fourths of the initial lodgings, of which more than a half had be reauthorized and registered at a higher ranking. This suggests, in fact, that locals have assessed the potential of tourism related businesses and that they have understood that the provision of decent services from a qualitative point of view increases their destination’s attractiveness; thus, their main focus seems to be the provision of lodgings services with good value-for-money. A highly encouraging fact is that despite the difficulties determined by the COVID-19 pandemic, this year indicates the maintenance of the investors’ interest towards the hospitality sector, with a growing trend of small lodgings, particularly rooms to let and apartments for rent. This novel orientation suggests the desire of the entrepreneurs to capitalize on the tourists’ current needs, namely, to travel and accommodate, under safe conditions, thus turning towards smaller scale lodgings, in the countryside, where they are provided intimacy and sufficient social distance.

On the other hand, the analyses also indicated that two areas are not yet properly covered by the local business-persons, namely foodservices and travel services. Thus, the authorized supply of foodservices is still very underdeveloped, not diversified, and fails to contribute to the region’s differentiation as a tourist destination. Specialized restaurants and restaurants with local and national specificity are practically missing from the local market’s offer. The situation is very odd as long as Mărginimea Sibiului seems to fail to capitalize on its statute of gastronomic destination of Europe.

Furthermore, travel agencies are practically absent from the region. Despite its positive image both in Romania and abroad, Mărginimea Sibiului does not benefit from an appropriate destination management. There has not yet been established a destination management organization (DMO) for the area, nor has one been developed for Sibiu County. Only three localities have tourist information centers (TICs): Rășinari (since 2010), Săliște (since 2013), and Tălmaciu (since 2020). Many things can and should be done in the region in this respect.

Another interesting finding of the desk analyses is the entrepreneurial profile of the players in the hospitality sector of the destination under scrutiny. Thus, from the point of view of sustainable development, it may be considered that having largely opted for the opening and management of lodgings but also of foodservices under sole entrepreneurship solutions as well as having massively chosen legal forms, such as authorized person, family association, individual enterprise, or family enterprise, indicates the entrepreneur’s desire to provide for his/her family and to increase their wellbeing. The promotion of agritourism and rural tourism in Mărginimea Sibiului creates opportunities for local and regional economic growth; it also helps create new jobs through harnessing the specific cultural and natural heritage. Moreover, the diversity of accommodation services creates new opportunities for the employment of youth from the region and has proven to be a female-coordinated activity.

This is another sector worth exploring for local entrepreneurs because the region presents a large variety of attractions and very diversified leisure opportunities which have great potential to be integrated into successful travel packages. Given the high notoriety of the area at the international level, there are plenty of business opportunities for incoming travel services.