Towards More Balanced Territorial Relations—The Role (and Limitations) of Spatial Planning as a Governance Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Towards a More Balanced, Sustainable and Territorially Integrated Development

1.2. Recent Research on the Role of Spatial Planning in Determining Territorial Relations

- The increasing importance of more distributed and collaborative models of planning and decision-making, and what this means for the impact of spatial planning on territorial relations.

- The role of civic engagement in planning, the ways it is achieved and its impact on the quality of planning processes.

- The trend towards peri-urbanisation, which involves issues of land use planning, landscape management, conservation, infrastructure provision and social exclusion.

- The increasing importance of development concepts that aim at orienting regional resources towards the competitive strengths and goals of a region.

- The move from the functional segregation of rural and urban space, and land uses, towards more integrated perspectives and towards planning rural and urban areas together.

- The Town and Country Planning Act 1947 in the UK provides an example of a system of development control designed to enforce the separation of rural and urban space [16]. Boelens (2011) and Busck et al. (2009) found similar patterns in the Netherlands, where functional segregation and spatial quality have informed the strict compartmentalisation of urban and rural land uses. Connected, the rural character of territories is protected through restricted development. Building is only allowed with planning permission, and planning permission is only granted if the municipal plan has designated a place as apt for (a specific type of) buildings [17,18].

- In the UK and in Germany, green belts have historically succeeded in tightly constraining the built-up areas of major cities. Murdoch and Marsden (1994) argue that green belts have also in effect produced a displaced suburbanisation, with out-migrants from cities “leapfrogging” protected areas and driving settlement growth and housing development in rural areas beyond the greenbelt [19]. Gallent et al. (2008) suggest that new settlements were directed to the rural-urban fringe, not because of proactive spatial planning, but because the transitional zone of the fringe was the least contentious [20]. The same authors add that a closely related instrument is the drawing of development envelopes around smaller towns and villages.

- The city–countryside partnerships in Germany aimed at enabling urban and rural areas to take over responsibility for larger territories [24]. Projects were to benefit the entire territory through development across rural-urban divides. The basic idea was that growth and innovation can be promoted regionally in a better way when the potentials of urban and rural areas are combined, and when these are not treated as separate spheres. An associated aim was to promote sustainable development of larger city-regions through an improved and jointly coordinated decision-strategy between public and private actors [25].

- The Wales Spatial Plan (WSP), produced in 2004, is an example of planning rural and urban areas together [26]. The WSP articulated a national spatial planning vision for Wales that is based on six functional regions encompassing both rural and urban localities, differentiated by fuzzy boundaries. The approach has its limitations, as emphasised by Heley (2013), who argues that the WSP has impacted the consciousness and networks of policy makers and political actors, while its ability to shape and instigate change “on the ground” has been limited [27].

1.3. Key Questions Addressed in This Article

2. Methodology and Empirical Basis

2.1. Methodology, Analytical Framework and Criteria

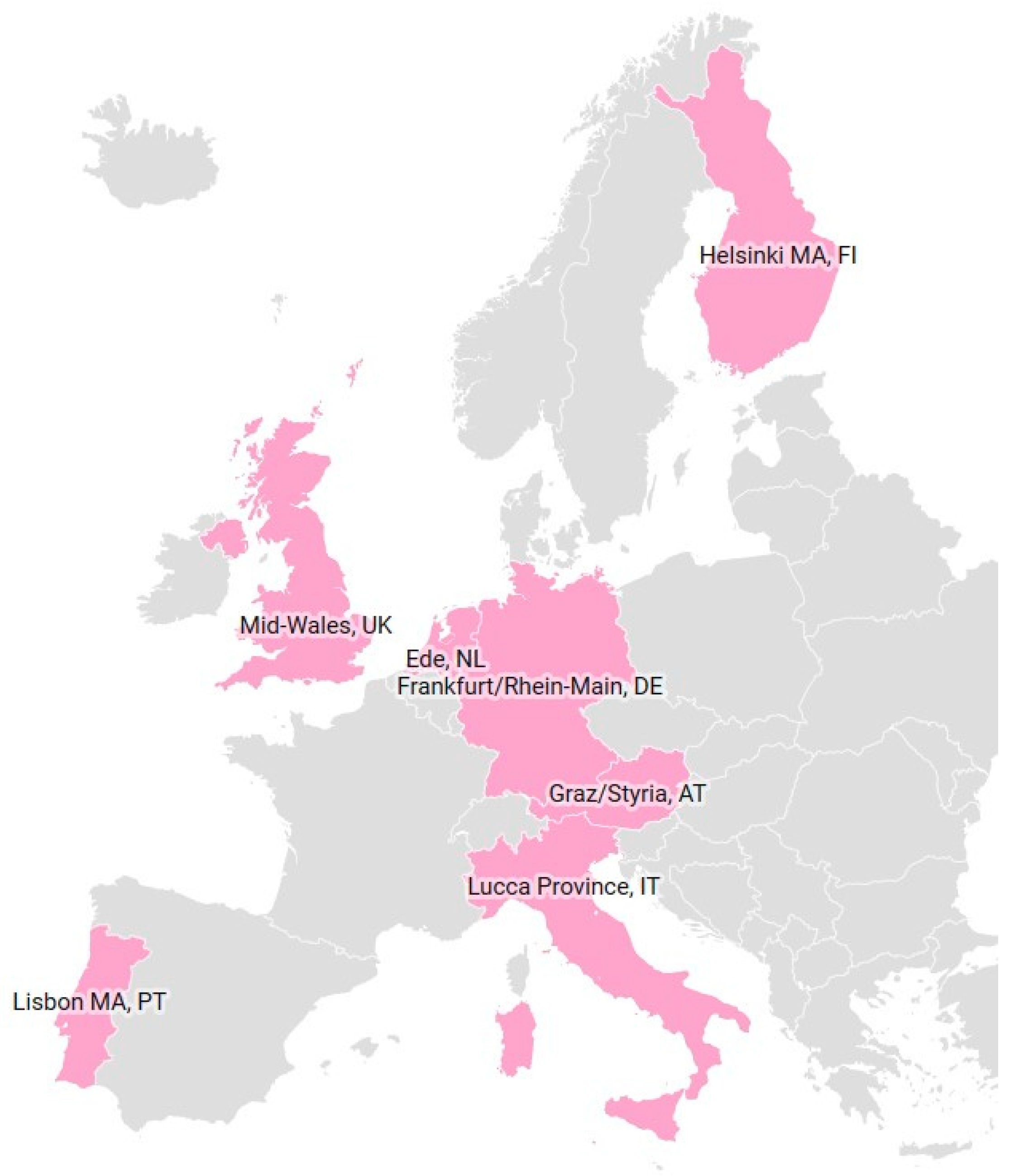

2.2. Empirical Basis

3. Analysis and Discussion

- The role that the relations between urban, peri-urban and rural areas play in current territorial governance arrangements and in spatial planning.

- The role civic engagement plays for the outcomes of spatial planning.

- The mechanisms, processes and instruments that are in place to ensure plan implementation.

3.1. The Roles That the Relations Between Urban, Peri-Urban and Rural Areas Play in Spatial Planning and in Current Territorial Governance Arrangements

3.2. The Role Civic Engagement Plays for the Outcomes of Spatial Planning

3.3. The Mechanisms, Processes and Instruments That Are in Place to Ensure Plan Implementation

3.4. A Synopsis of Key Findings

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Romeo, L. What is territorial development? GREAT Insights Mag. 2015, 4, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, S.; van der Ven, H. Best practices in global governance. Rev. Int. Stud. 2017, 43, 534–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Habitat. International Guidelines on Urban and Territorial Planning, towards a Compendium of Inspiring Practices; United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Allmendinger, P. Planning Theory; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shucksmith, M. Disintegrated Rural Development? Neo-endogenous Rural Development, Planning and Place-Shaping in Diffused Power Contexts. Sociol. Rural. 2010, 50, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldi, L.; Nilsson, P.; Westlund, H.; Wixe, S. What is smart rural development? J. Rural. Stud. 2015, 40, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachhaltigkeitsrat. Perspectives for Germany, Our Strategy for Sustainable Development. 2005. Available online: http://www.nachhaltigkeitsrat.de/service/download/publikationen/broschueren/Broschuere_Nachhaltigkeit_und_Gesellschaft.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Fürst, D. Regional governance—ein neues Paradigma der Regionalwissenschaften? Raumforsch. Raumordn. 2001, 59, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knickel, K. New divisions of responsibilities in rural areas, nature management and environmental education, Some relevant experiences in Germany. Essay prepared for the National Council of Rural Affairs in The Netherlands. 2005; Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P.; Booher, D.E.; Torfing, J.; Sørensen, E.; Ng, M.K.; Peterson, P.; Albrechts, L. Civic Engagement, Spatial Planning and Democracy as a Way of Life Civic Engagement and the Quality of Urban Places Enhancing Effective and Democratic Governance through Empowered Participation, Some Critical Reflections One Humble Journey towards Planning for a More Sustainable Hong Kong, A Need to Institutionalise Civic Engagement Civic Engagement and Urban Reform in Brazil Setting the Scene. Plan. Theory Pr. 2008, 9, 379–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, N.; Kreibich, V. (Eds.) Europe’s City-Regions Competitiveness, Growth Regulation and Periurban Land Management; Von Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Busck, A.G.; Hidding, M.C.; Kristensen, S.B.P.; Persson, C.; Præstholm, S. Planning approaches for rurban areas, Case studies from Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands. Geogr. Tidsskr. J. Geogr. 2009, 109, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briquel, V.; Collicard, J.J. Diversity in the rural hinterlands of European cities. In The City’s Hinter-Land, Dynamism and Divergence in Europe’s Periurban Territories; Hoggart, K., Ed.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2005; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. The Treatment of Space and Place in the New Strategic Spatial Planning in Europe. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 28, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart Specialisation Strategy (S3) Platform. Available online: https://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Allmendinger, P.; Haughton, G. The Fluid Scales and Scope of UK Spatial Planning. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2007, 39, 1478–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens. Compacte Stad Extended, Agenda voor toekomstig belied, onderzoek en ontwertp. In Compact City Extended, Outline for Future Policy, Research and Design; Uitgeverj 010: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Busck, A.G.; Hidding, M.C.; Kristensen, S.B.P.; Persson, C.; Præstholm, S. Managing rurban landscapes in the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden: Comparing planning systems and instruments in three different contexts. Dan. J. Geogr. 2008, 108, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch, J.; Marsden, T.K. Reconstituting Rurality, the Changing Countryside in an Urban Context; UCL Press: London, UK, 1994; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Gallent, N.; Juntti, M.; Kidd, S.; Shaw, D. Introduction to Rural Planning; Routledge India: New Delhi, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Haughton, G.; Allmendinger, P.; Counsell, D.; Vigar, G. The New Spatial Planning, Territorial Management with Soft Spaces and Fuzzy Boundaries; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ESPON. Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/planning-systems (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Brown, D.L.; Shucksmith, M. Reconsidering territorial governance to account for enhanced rural-urban interdependence in America. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2017, 672, 282–301. [Google Scholar]

- BMVBS. Stadt-Land-Partnerschaften-Wachstum und Innovation Durch Kooperation; Bundesministerium für Verkehr, Bau und Stadtentwicklung: Bonn, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Obersteg, A.; Knieling, J.; Jacuniak-Suda, M. Urban-rural partnerships in metropolitan areas (and beyond). In Mobilising Regions, Territorial Strategies for Growth; Region-al Studies Association: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heley, J. Wales Spatial Plan. Rapid Appraisal Report, Rural-Urban Governance Arrangements and Planning Instruments; Aberystwyth University: Aberystwyth, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heley, J. Soft Spaces, Fuzzy Boundaries and Spatial Governance in Post-devolution Wales. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 37, 1325–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ROBUST—Unlocking Rural-Urban Synergies, EU Horizon 2020. Available online: http://rural-urban.eu/ (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Galli, F.; Rovai, M. Law of Tuscany Region 65/2014 on the Government of the Territory. Rapid Appraisal Report, Rural-Urban Governance Arrangements and Planning Instruments, DAFE; University of Pisa: Pisa, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Henke, R. Regional Land Use Plan. Rapid Appraisal Report, Rural-Urban Governance Arrangements and Planning Instruments; Frankfurt/Rhein-Main, Germany, 2018; Unpublished project paper. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bauchinger, L. Law on Planning and Development of the Province of Styria and its Regions. Rapid Appraisal Report, Rural-Urban Governance Arrangements and Planning Instruments, Metropolitan Area of Styria; Austria/Federal Institute of Agricultural Economics, Rural and Mountain Research: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lahdelma, T. MAL Agreement, Regional Cooperation on Land Use, Housing and Transport. Rapid Appraisal Report, Rural-Urban Governance Arrangements and Planning Instruments; Helsinki, Finland, 2018; Unpublished project paper. [Google Scholar]

- Pina, C. Regional Spatial Plan for the Territory of the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (PROT-AML). Rapid Appraisal Report, Rural-Urban Governance Arrangements and Planning Instruments; CCDR-LVT: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J. Networks of connectivity, territorial fragmentation, uneven development, the new politics of city-regionalism. Political Geogr. 2010, 29, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.; Heley, J. Governing beyond the metropolis, placing the rural in city-region development. Urban Stud. 2014, 52, 1113–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, M. From City-region Concept to Boundaries for Governance, The English Case. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 2426–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostindie, H. Netherlands Environment and Planning Act (NEPA). Rapid Appraisal Report, Rural-Urban Governance Arrangements and Planning Instruments; Ede, The Netherlands, 2018; Unpublished project paper. [Google Scholar]

- Arcuri, S.; Galli, F.; Rovai, M. Community for Food and Agro-Biodiversity. Rapid Appraisal Report, Rural-Urban Governance Arrangements and Planning Instruments, DAFE; University of Pisa: Pisa, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nadin, V. The state of spatial planning systems in Europe and their capacity to meet the challenges of intense urban and regional flows. In Proceedings of the Warsaw Regional Forum, Warsaw, Poland, 18–20 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Beattie, L. Spatial Planning and Urban—Implementation Challenges; School of Architecture and Planning, The University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. Are city-regions the answer? In The Future of Regional Policy, 50–59; Tomaney, J., Ed.; Regional Studies Association/Smith Institute: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M. Rural geography, blurring boundaries and making connections. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2009, 33, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A European Green Deal, Striving to Be the First Climate-Neutral Continent. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- European Commission. Future of the Common Agricultural Policy. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/key-policies/common-agricultural-policy/future-cap_en (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Peters, B.G. The challenge of policy coordination. Policy Des. Pr. 2018, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Main Goal |

|---|---|

| Spatial planning | Mediating between the respective claims on space of the state, market and community; coordinating practices and policies affecting spatial organisation. |

| Territorial planning | Realising economic, social, cultural and environmental goals through the development of spatial visions, strategies and plans, as well as the application of policy tools, institutional and participatory mechanisms and regulatory procedures. |

| Regional planning | Addressing region-wide economic, social and environmental issues, including efficient placement of infrastructure, settlements, industrial spaces and nature reserves. |

| Land use planning | Ordering and regulating the use of land to mitigate land use conflicts, foster environmental conservation, limit urban sprawl and minimise transport costs. |

| Territorial Relations and Development | Civic Engagement and Planning Process | Coherence in Territorial Governance |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Region | Area | Population | Central Challenge in Regional Development * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | Density inh./sqkm | Change ** % | ||

| Ede, NL | 318 | 364 | +0.9% | Increased provision of ecosystem services, diversification and territory-based cooperation |

| Frankfurt/Rhein-Main, DE | 2458 | 960 | +1.2% | Rebalancing economic and environmental goals, increasing ecosystem services provision and quality of life |

| Helsinki, FI | 9568 | 176 | +1.0% | Achieving a balanced development of the larger metropolitan region and strengthening of local economic relations |

| Lisbon Metropolitan Area, PT | 3015 | 944 | +1.3% | Strengthening of local economic relations for a harmonised and integrated territorial development |

| Lucca Province, IT | 1773 | 220 | −0.1% | Valorising territory, landscape and cultural heritage, and preserving social, environmental and cultural values |

| Mid-Wales, UK | 17,034 | 60 | −0.2% | Encouraging smart growth, maintaining landscapes, natural resources, and the distinctive Welsh culture and language |

| Metropolitan Area of Styria, AT | 1890 | 261 | +1.1% | Fostering intercommunal cooperation in public infrastructure, social services, new businesses and cultural activities, enhancing quality of life |

| Name | Brief Description | Type * | Year | Ref. ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch Environment and Planning Act and its implementation in Ede | Aims to enhance the place-based integration of existing spatial planning, environmental and nature-oriented regulatory frameworks. | SP | 2016 | EDE4 |

| Regional Land Use Plan Frankfurt/Rhein-Main and its update | A tailor-made modification of land use planning which covers the area of 75 (from 1 April 2021: 80) municipalities and is elaborated by the Regionalverband FrankfurtRheinMain. | LUP | 2010 | FRA1 |

| Law on Planning and Development of the Province of Styria and its regions | The law defines the tasks of the province and of its seven regions and the scope for intercommunal projects to be financed by the regions. | TP | 2018 | GRA1 |

| Agreement on land use, housing and transport in Helsinki region (MAL) | The 14 municipalities in Helsinki region cooperate in land use, housing and transport. MAL describes the common intent, including a shared land use plan and housing strategy. | RP | 2020 | HEL1 |

| Regional Spatial Plan for Territory of Lisbon Metropolitan Area (PROT-AML) | The aim is to enable a coherent structuring of the Lisbon Metropolitan territory. It is a strategic plan that is to achieve its goals is by integrating norms into the Municipal Plans. | SP | 2002 | LIS2 |

| Law of Tuscany Region 65/2014 and its implementation in Lucca Province | The aim is to enhance sustainable development, counteract land consumption and promote the multifunctional role of the rural territory. Public participation in drawing up the plans. | TP | 2014 | LUC1 |

| Wales Spatial Plan (WSP), now: National Development Framework (NDF) 1 | Strategy for sustainable development with national spatial priorities across key sectors, including health, education, housing, economy, environmental and landscape management. | SP | 2008 | MWA1 |

| Region | Type of Planning | Level of CS Involvement | Kind and Role of CS Involvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch Environment and Planning Act, implementation in Ede | SP | medium | stakeholders |

| Regional Land Use Plan Frankfurt/Rhein-Main | LUP | medium | representative |

| Law on Planning and Development of the Province of Styria and its regions | TP | medium | stakeholders |

| Agreement on land use, housing and transport in Helsinki region (MAL) | RP | medium | open discussions |

| Regional Spatial Plan for Territory of Lisbon Metropolitan Area (PROT-AML) | SP | medium | advisory committee |

| Law of Tuscany Region 65/2014, implementation in Lucca Province | TP | high | citizens, stakeholders |

| Wales Spatial Plan, now National Development Framework (NDF) | SP | medium | representative |

| Case Study Plan | Territorial Relations and Development | Civic Engagement and Planning Process | Coherence in Territorial Governance | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| Dutch Environment and Planning Act and its implementation in Ede | m | m | m | m | m | h | h | h | m | |||

| Regional Land Use Plan Frankfurt/Rhein-Main | m | h | m | m | h | m | ||||||

| Law on Planning and Development, Province of Styria and its regions | m | m | m | h | m | m | m | h | h | h | ||

| Agreement on land use, housing and transport in Helsinki region | m | m | m | m | h | h | ||||||

| Regional Spatial Plan for Territory of Lisbon Metropolitan Area | m | m | m | h | m | m | m | m | ||||

| Law of Tuscany Region 65/2014, implementation in Lucca Province | m | m | h | m | m | m | h | m | h | m | ||

| Wales Spatial Plan, now National Development Framework (NDF) | m | m | m | m | ||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Knickel, K.; Almeida, A.; Bauchinger, L.; Casini, M.P.; Gassler, B.; Hausegger-Nestelberger, K.; Heley, J.; Henke, R.; Knickel, M.; Oostindie, H.; et al. Towards More Balanced Territorial Relations—The Role (and Limitations) of Spatial Planning as a Governance Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5308. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095308

Knickel K, Almeida A, Bauchinger L, Casini MP, Gassler B, Hausegger-Nestelberger K, Heley J, Henke R, Knickel M, Oostindie H, et al. Towards More Balanced Territorial Relations—The Role (and Limitations) of Spatial Planning as a Governance Approach. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):5308. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095308

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnickel, Karlheinz, Alexandra Almeida, Lisa Bauchinger, Maria Pia Casini, Bernd Gassler, Kerstin Hausegger-Nestelberger, Jesse Heley, Reinhard Henke, Marina Knickel, Henk Oostindie, and et al. 2021. "Towards More Balanced Territorial Relations—The Role (and Limitations) of Spatial Planning as a Governance Approach" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 5308. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095308

APA StyleKnickel, K., Almeida, A., Bauchinger, L., Casini, M. P., Gassler, B., Hausegger-Nestelberger, K., Heley, J., Henke, R., Knickel, M., Oostindie, H., Ovaska, U., Pina, C., Rovai, M., Vulto, H., & Wiskerke, J. S. C. (2021). Towards More Balanced Territorial Relations—The Role (and Limitations) of Spatial Planning as a Governance Approach. Sustainability, 13(9), 5308. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095308