Cultural Tourism in Nitra, Slovakia: Overview of Current and Future Trends

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

- -

- In a narrow sense—it is limited to the monuments of material culture, which were built at their respective places by previous generations, or are concentrated in museums and galleries,

- -

- In a broader sense—it includes all manifestations of culture as a whole, i.e., material and immaterial results of human activities, which are collected, stored, and evaluated in the course of human history, and passed from generation to generation.

- Demographic—satisfaction of requirements, such as educated clients and/or elderly clients; comfort and quality, resulting in the creation of products aimed at individuals,

- Educational—the packages include elements of culture (theater performance), creative presentation of information, requirement of authenticity,

- Lifestyle—new products, which are related to tourist interests

- Information and communication technology—information is transmitted electronically, growing importance of visual presentations.

- -

- Does the city of Nitra, with its original agricultural and trade fair tradition, have the potential to become a center of cultural tourism in the context of the development of cultural routes?

- -

- To what extent can cultural routes help the city of Nitra in terms cultural ecosystems services?

- -

- What were the effects of the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic on cultural tourism in Nitra?

3. Methodology

4. Nitra in Cultural Tourism Framework

5. Results

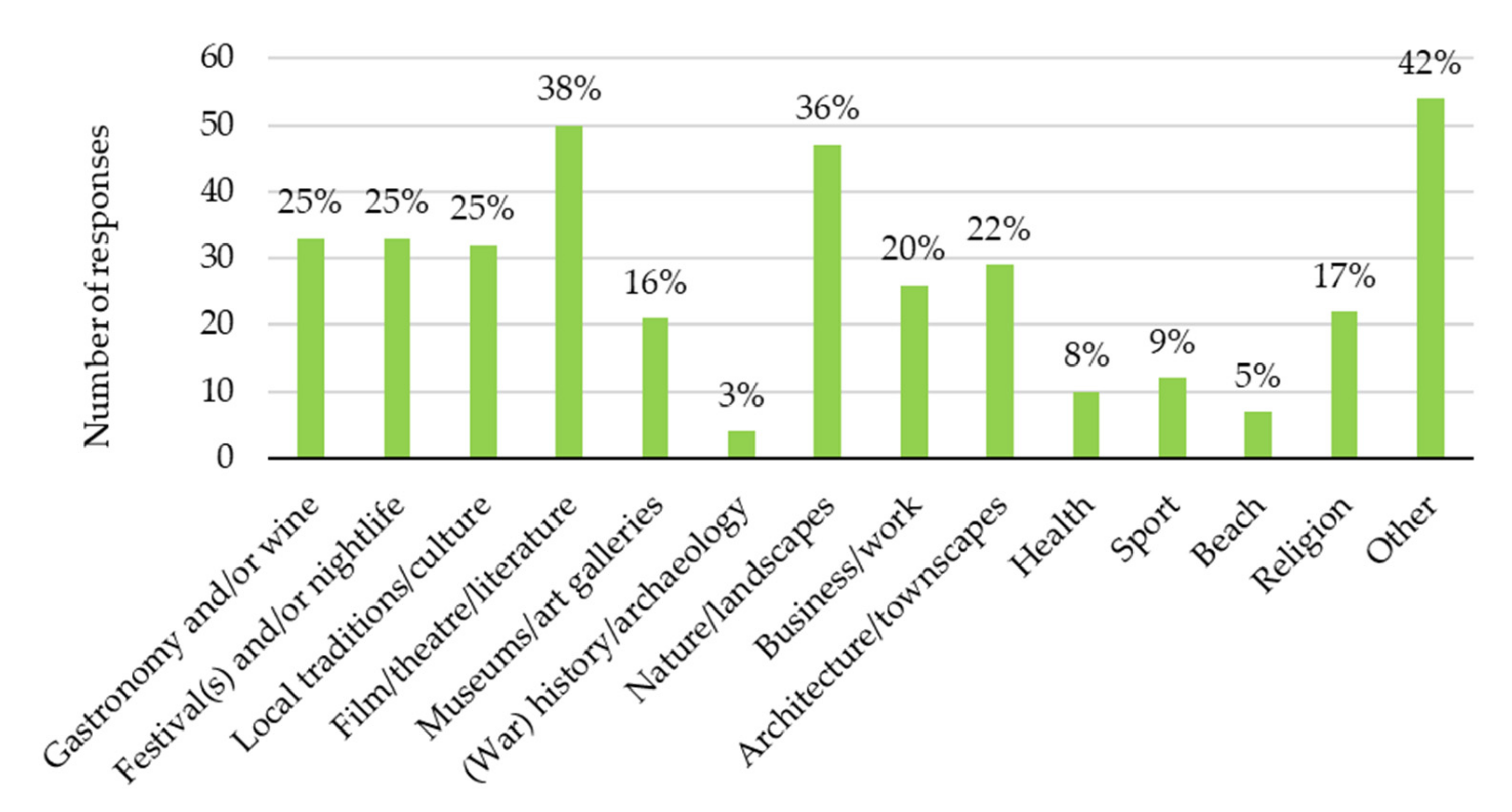

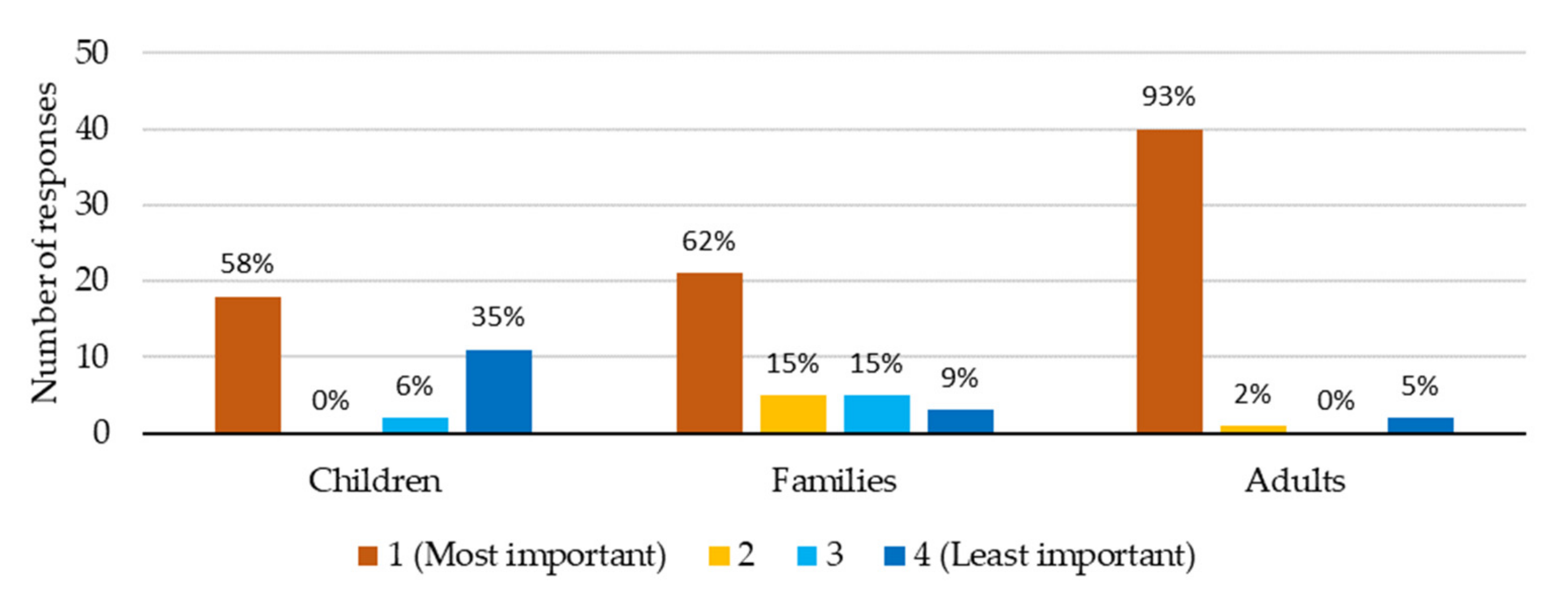

5.1. Selected Results of Questionnaire Surveys

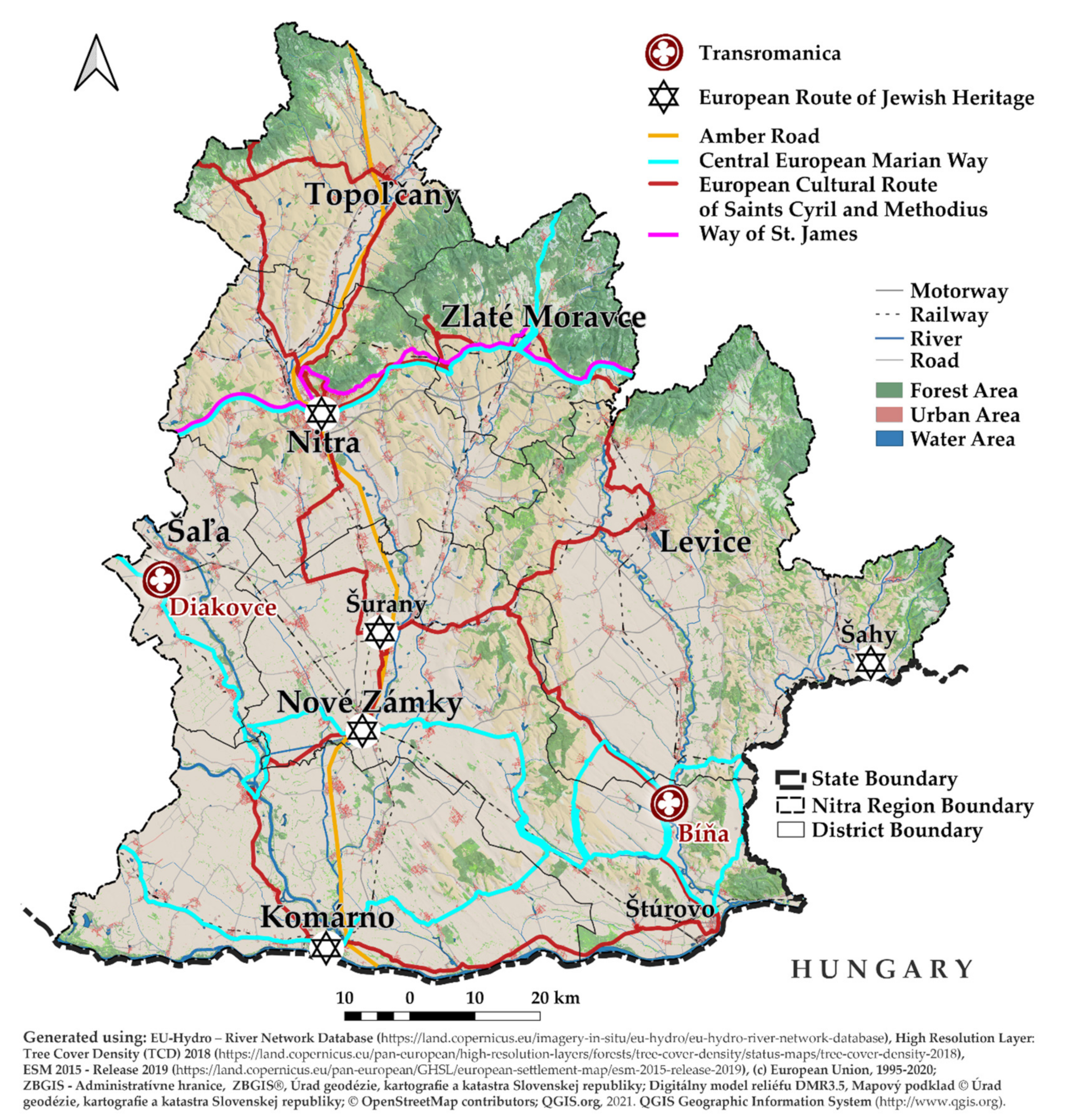

5.2. Cultural and Other Routes—Their Potential for the Development of Cultural Tourism in the City of Nitra and its Greater Area

6. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boniface, P. Managing Quality Cultural Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 1995; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Tourism attraction systems: Exploring cultural behaviour. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 1048–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.C. Corporate social responsibility: Not whether, but how. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeldner, C.R.; Richie, B., Jr. Cestovní Ruch, Principy, Příklady, Trendy; Albatros Media BizBooks: Praha, Czech Republic, 2014; p. 545. [Google Scholar]

- Millenium ecosystem assessment. Ecosystems and Human WellBeing: A Framework for Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 528–546. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, C.D.; Muhar, A.; Arnberger, A.; Aznar, O.; Boyd, J.W.; Chan, K.M.; Costanza, R.; Elmqvist, T.; Flint, C.G.; Gobster, P.H.; et al. Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8812–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braat, L.C.; de Groot, R. The ecosystem services agenda: Bridging the worlds of natural science and economics, conservation and development, and public and private policy. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 1, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieling, C.; Plieninger, T.; Pirker, H.; Vogl, C.R. Linkages between landscapes and human well-being: An empirical exploration with short interviews. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 105, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Kizos, T.; Bieling, C.; Le DÛ-Blayo, L.; Budniok, M.A.; Bürgi, M.; Crumley, C.L.; Girod, G.; Howard, P.; Kolen, J. Exploring ecosystem-change and society through a landscape lens: Recent progress in European landscape research. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrbičanová, G.; Kaisová, D.; Močko, M.; Petrovič, F.; Mederly, P. Mapping cultural ecosystem services enables better informed nature protection and landscape management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mederly, P.; Černecký, J. A Catalogue of Ecosystem Services in Slovakia: Benefits to Society; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; ISBN 978-3030465087. [Google Scholar]

- Daily, G.C. Developing a scientific basis for managing earth’s life support systems. Ecol. Soc. 1999, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, R.S.; Wilson, M.A.; Boumas, R.M.J. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J.; Banzhaf, S. What are ecosystem services? The need for standardized environmental accounting units. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 63, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. (Ed.) The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity: Ecological and economic foundations. In The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB); United Nations Environment Programme: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, K.J. Classification of ecosystem services: Problems and solutions. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 39, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, D.A. (Ed.) Cultural and Spiritual Values of Biodiversity; Intermediate Technology: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sponsel, L. Do anthropologists need religion, and vice versa? Adventures and dangers. In Spiritual Ecology. New Directions in Anthropology and Environment: Intersections; Crumley, C.L., Ed.; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, V.W.; Mooney, H.A.; Cropper, A.; Capistrano, D.; Carpenter, R.S.; Chopra, K.; Dasgupta, P.; Dietz, T.; Duraiappah, K.A.; Hassan, R.; et al. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Balmford, A.; Bruner, A.; Cooper, P.; Costanza, R.; Farber, S.; Green, R.E.; Jenkins, M.; Jefferiss, P.; Jessamy, V.; Madden, J.; et al. Economic reasons for conserving wild nature. Science 2002, 297, 950–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, R. Function-analysis and valuation as a tool to assess land use conflicts in planning for sustainable, multi-functional landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, M.L.; Nolan, S. Religious sites as tourism attractions in Europe. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, J.; Fabrega, N.; Zulian, G.; Barbosa, A.; Vizcaino, P.; Ivits, E.; Polce, C.; Vandecasteele, I.; Rivero, I.M.; Guerra, C.; et al. Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services: Trends in Ecosystems and Ecosystem Services in the European Union Between 2000 and 2010 Luxembourg; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015; p. 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, E. Defining the Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe. Cultural Routes Management: From Theory to Practice. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. 2015. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/2017-activity-report-full-doc-cultural-routes-of-the-council-of-europe/168078ea38 (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Resolution CM/Res (2010) 53 on the Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe. 1680. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16805cdb50 (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Resolution CM/Res (2013) 66 on the Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe. 1680. Available online: https://search.coe.int/cm/Pages/result_details.aspx?ObjectID=09000016805c69ac (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Resolution CM/Res (2013) 67 on the Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe. 1680. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16807b7d5b (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Collins-Kreiner, N. Geographers and pilgrimages: Changing concepts in pilgrimage tourism research. Tijdschrift Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2010, 101, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, T. The St. Olav’s Way—The origin, nature and trends in development of pilgrimage activity in Scandinavia. Peregrinus Crac. 2016, 27, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maak, K. The way of St. James as a potential touristic power in rural, structurally lagging regions: The case of Brandenburg. Cuadernos Tur. 2009, 23, 149–172. [Google Scholar]

- Mróz, F.; Mróz, L.; Krogmann, A. Factors conditioning the creation and development of a network of Camino de Santiago routes in visegrad group countries. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2019, 7, 56–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrósio, V.; Fernandes, C.; Goretti, S.; Cabral, A. A conceptual model for assessing the level of development of Pilgrimage routes. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2020, 7, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horák, M.; Kozumplíková, A.; Somerlíková, K.; Lorencová, H.; Lampartová, I. Religious tourism in the south-Moravian and Zlín regions: Proposal for three new Pilgrimage routes. Eur. Countrys. 2015, 7, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterka, M. Cyrilometodějská stezka jako příležitost pro využití a interpretaci společného evropského kulturního dědičství. The Route of Cyril and Methodius as an Opportunity for the Use and Interpretation of the Common Euporean Cultural Heritage. Konštantínove Listy 2016, 9, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktuálny Ročný Komponent Výročnej Správy Ministerstva Kultúry Slovenskej Republiky za Rok 2014. Available online: https://www.culture.gov.sk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/vyrocna_sprava_MKSR_2014.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Gúčik, M. (Ed.) Cestovný Ruch—Hotelierstvo—Pohostinstvo; SPN: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2006; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Matlovičová, K.; Klamár, R.; Mika, M. Turistika a Jej Formy; PU v Prešove: Prešov, Slovakia, 2015; p. 550. [Google Scholar]

- WTO. Sustainable Tourism. 2020. Available online: https://tourismnotes.com/sustainable-tourism/ (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieckowski, M. Natural heritage as a resource for tourism development in the Polish Carpathians. Geogr. Časopis. 2020, 72, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juganaru, I.; Juganaru, M.; Anghel, A. Sustainable tourism types. Ann. Univ. Craiova Econ. Sci. Ser. 2008, 2, 797–804. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.M.; Goldstein, J.; Satterfield, T.; Hannahs, N.; Kikiloi, K.; Naidoo, R.; Vadeboncoeur, N.; Woodside, U. Cultural services and non-use values. In The Theory and Practice of Ecosystem Service Valuation in Conservation; Kareiva, P., Daily, G., Ricketts, T., Tallis, H., Polasky, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 206–228. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G.; Margues, L. Available online: http://www.agenda21culture.net (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Calabrò, F.; Campolo, D.; Cassalia, G.; Tramontana, C. Evaluating cultural routes for a network of competitive cities in the Mediterranean Sea: The eastern monasticism in Western Mediterranean area. Adv. Mater. Res. 2015, 1073, 1418–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campolo, D.; Bombino, G.; Meduri, T. Cultural landscape and cultural routes: Infrastructure role and indigenous knowledge for a sustainable development of inland areas. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukonić, B. Religious Tourism: Economic Value or an Empty Box? Zagreb Internat. Rev. Econ. Bus. 1998, 1, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bogacz-Wojtanowska, E.; Góral, A.; Bugdol, M. The role of trust in sustainable heritage management networks. case study of selected cultural routes in Poland. Sustainability 2017, 11, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, D. Heritage and wine as tourist attractions in rural areas. In Proceedings of the 116th EAAE Seminar on Spatial Dynamics in Agri-Food Systems: Implications for Sustainability and Consumer Welfare, Parma, Italy, 27–30 October 2010; p. 95216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mănilă, M. Wine tourism–A great tourism offer face to new challenges. J. Tour. 2012, 13, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Montella, M.M. Wine tourism and sustainability: A review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, E.; Mariotti, A. The heritage of Cultural Routes: Between landscapes, traditions and identity. In Cultural Routes Management: From Theory to Practice; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2015; pp. 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- European Route of Jewish Heritage. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/cultural-routes/the-european-route-of-jewish-heritage (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Mitoula, R.; Maniou, F.; Mpletsos, G. Urban cultural tourism and cultural routes. As a case study: The city of Rome. Sustain. Develop. Cult. Tradit. J. 2020, 1, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabbini, E. Cultural routes and intangible heritage. AlmaTourism 2012, 3, 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Moscarelli, R.; Lopez, L.; González, R.C.L. Who is interested in developing the way of Saint James? The Pilgrimage from faith to tourism. Religions 2020, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, S.; Tomić, N. Developing the cultural route evaluation model (CREM) and its application on the trail of Roman Emperors, Serbia. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 17, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breaking Point Nitra 26. European Capital of Culture Candidate City Pre-Selection Bid Book. Nitra 2026. Available online: https://www.nitra2026.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Nitra2026_ECoC_PreSelection_Bidbook.pdf. (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- SPOT. Social and Innovative Platform on Cultural Tourism and its Potential towards Deepening Europeanisation. Available online: http://www.spotprojecth2020.eu/ (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Korec, P.; Popjaková, D. Priemysel v Nitre: Globálny, Národný a Regionálny Kontext. Bratislava: Univerzita Komenského. 2019. Available online: http://www.humannageografia.sk/stiahnutie/nitra_priem_korec_popjakova_2019.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Ivanič, P.; Labanc, P.; Hetényi, M. Cestná sieť a výber cestného mýta v oblasti Ponitria v stredoveku v kontexte písomných prameňov. In Výzkum Historických Cest v Interdisciplinárním Kontextu 2019; Martínek, J., Ed.; Centrum dopravního výzkumu: Brno, Czech Republic, 2020; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Krogmann, A. Modell-analyse des fremdenverkehrs in der Stadt Nitra. Arbeitsmaterialien Raumordnung Raumplanung 2005, 240, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrósio, V.; Fernandes, C.; Krogmann, A.; Leitão, I.; Oremusová, D.; Petrikovičová, L. From church perseverance in authoritarian states to today’s religious inspired tourism. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrimonio Cult. 2019, 17, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diecézne Múzeum. Available online: https://www.muzeum.sk/diecezne-muzeum-nitra.html (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Diecézna Knižnica. Available online: http://www.biskupstvo-nitra.sk/institucie/diecezna-kniznica/ (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Hrubalová, L.; Palenčíková, Z.; Repáňová, T. Perception of the city by future and current visitors. In Proceedings of the International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts SGEM2016, Albena, Bulgaria, 29 September 2016; pp. 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasagranda, A.; Gurňák, D.; Danielová, K. Congress tourism and fair tourism of Slovakia-quantification, spatial differentiation, and classification. Reg. Stat. 2017, 7, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogmann, A.; Kramáreková, H.; Petrikovičová, L. Religiózny Cestovný Ruch v Nitrianskej Diecéze; UKF v Nitre: Nitra, Slovakia, 2020; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Pivarčiová, A.; Zaujecová, T.; Palenčíková, Z. Stratégia Cestovného Ruchu v Meste Nitra na Roky 2021–2031. Analytická Časť. Available online: https://visitnitra.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Strat%C3%A9gia-rozvoja-cestovn%C3%A9ho-ruchu-v-meste-Nitra-na-roky-2021-2031.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Richards, G. Production and consumption of European cultural tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turistické Informačné Centrum Nitra. Available online: https://www.nitra.eu (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Nitrianska Organizácia Cestovného Ruchu. Available online: https://visitnitra.eu/sk/ (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Elexová, Ľ.; Lelovská, R. Rozvoj Udržateľného Cestovného Ruchu a Certifikovaných Značiek v Destinácii Nitra 2020–2025. Available online: https://visitnitra.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Rozvoj-udr%C5%BEate%C4%BEn%C3%A9ho-cestovn%C3%A9ho-ruchu-a-certifikovan%C3%BDch-zna%C4%8Diek-v-destin%C3%A1cii-Nitra_2020-25-WEB.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Nitra na 7 Pahorkoch. Available online: https://www.nitra.eu/ (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Cesty Mladého Corgoňa. Available online: https://www.nitra.eu/sprava/12138/stiahnite-si-aplikaciu-cesty-mladeho-corgona.html (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Palenčíková, Z. Stratégia Cestovného Ruchu v MESTE Nitra na Roky 2021–2031. Návrhová Časť. 2020. Available online: https://www.nitra.eu/data/news_files/nitra.eu/18799/strategia-rozvoja-cr-2021-2031-strategicka-cast.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Pohner, T.; Berki, T.; Rátz, T. Religious and pilgrimage tourism as a special segment of mountain tourism. J. Tour. Chall. Trends 2009, 2, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, R. Pilgrimages; The Boydell Press: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Collins-Kreiner, N. The geography of pilgrimage and tourism: Transformations and implications for applied geography. Appl. Geogr. 2010, 30, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, N. Researching pilgrimage. Continuity and transformations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukonić, B. Tourism and Religion; Elsevier Science Ltd.: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Vukonić, B. Religion, tourism and economics, a convenient symbiosis. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2002, 27, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimiás, A.; Michalkó, G. Religious tourism in Hungary—An integrative framework. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2013, 62, 175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Meri, Y. The cult of saints and pilgrimage. In The Oxford Handbook of the Abrahamic Religions; Silverstein, A.J., Stroumsa G., G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, C. Postscript: Anthropology as pilgrimage, anthopologist as pilgrim. In Sacred Journeys. The Anthropology of Pilgrimage; Morinis, A., Ed.; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 1992; pp. 257–274. [Google Scholar]

- Mróz, F. The Impact of COVID-19 on Pilgrimages and Religious Tourism in Europe During the First Six Months of the Pandemic. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 625–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago de Compostela Pilgrim Routes. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/cultural-routes/the-santiago-de-compostela-pilgrim-routes (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Explore all Cultural Routes by Theme. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/cultural-routes/by-theme (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Slovenská Cesta Židovského Kultúrneho Dedičstva. Available online: http://www.slovak-jewish-heritage.org/pagetitle.html?&L=1 (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Židovský Cintorín. Available online: https://www.nitra.eu/p/9013/zidovsky-cintorin.html (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- European Cultural Route of Saints Cyril and Methodius. Available online: https://www.cyril-methodius.cz/en/ (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Čo je Stredoeurópska Mariánska Cesta? Available online: https://www.mariaut.sk/sk/co-je-stredoeuropska-marianska-cesta (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Transromanica. The Romannesque Routes of European Heritage. Sales Manual. Available online: https://www.transromanica.com/downloads/sales-manual/ (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Bednár, P.; Ruttkay, M. Nitra and the Principality of Nitra after the Fall of Great Moravia. In Moravian and Silesian 7. Strongholds of the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries in the Context of Central Europe; The Czech Academy of Sciences, Institute of Archaeology: Brno, Czech Republic, 2018; pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Judák, V.; Bednár, P.; Medvecký, J. The Nitra Castle and Cathedral Church—Basilica of St. Emmeram. Nitra Bratislava; Plekanec & Haviar: Nitra, Slovakia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Welcome to Magna Via. Available online: http://www.magnavia.eu/o-projekte/welcome-to-magna-via (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Dinu, M.; Cohen, N.; Cioaca, A.; Dombay, S.; Nedelcu, A. Some models of thematic routes practiced in wine regions. Transylv. J. Tour. Territ. Dev. 2015, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kruzmetra, M.; Rivza, B.; Foris, D. Modernization of the demand and supply sides for gastronomic cultural heritage. Manag. Theory Stud. Rural. Bus. Infrastruct. Dev. 2018, 40, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchi, A.; Santini, C. Food and Wine Events in Europe: A Stakeholder Approach; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sekulić, D.; Petrović, A.; Dimitrijević, V. Who are wine tourists? An empirical investigation of segments in serbian wine tourism. Econ. Agric. 2017, 4, 1571–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trišić, I.; Snežana Štetić, S.; Donatella Privitera, D.; Nedelcu, A. Wine routes in Vojvodina Province, Northern Serbia: A tool for sustainable tourism development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitrianska Kráľovská Vínna Cesta. Available online: http://www.nkvc.eu/ (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Šťastná, M.; Vaishar, A.; Ryglová, K.; Rašovská, I.; Zámečník, S. Cultural cultural tourism as a possible driver of rural development in Czechia. wine tourism in Moravia as a case study. Eur. Countrys. 2020, 12, 292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, J.; Neuts, B. Territorial capital, smart tourism specialization and sustainable regional development: Experiences from Europe. Habit. Int. 2017, 1, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzić, A.; Bjeljac, Ž. Cultural routes—Cross-border tourist destinations within Southeastern Europe. Forum Geogr. 2016, 15, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, R.S.; Alkemade, R.L.; Braat, L.; Hein, L.; Willemen, L. Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecol. Complex. 2010, 7, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivarčiová, A. Dopad Pandémie na Poskytovateľov Služieb v Cestovnom Ruchu. 2021. Available online: https://visitnitra.eu/sk/pandemie-poskytovatelov-cestovnom/ (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Liang, X.; Lu, Y.; Martin, J.C. A review of the role of social media for the cultural heritage sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONplan Lab S.R.O. Stratégia Rozvoja Kultúry, Kreatívneho Priemyslu a Kultúrneho Cestovného Ruchu v Nitre na Roky. 2021–2031. 2020. Available online: https://visitnitra.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/NK31_Strat%C3%A9gia-rozvoja-kult%C3%BAry-kreat%C3%ADvneho-priemyslu-a-kult%C3%BArneho-CR-v-Nitre-2021-2031.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krogmann, A.; Ivanič, P.; Kramáreková, H.; Petrikovičová, L.; Petrovič, F.; Grežo, H. Cultural Tourism in Nitra, Slovakia: Overview of Current and Future Trends. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095181

Krogmann A, Ivanič P, Kramáreková H, Petrikovičová L, Petrovič F, Grežo H. Cultural Tourism in Nitra, Slovakia: Overview of Current and Future Trends. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):5181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095181

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrogmann, Alfred, Peter Ivanič, Hilda Kramáreková, Lucia Petrikovičová, František Petrovič, and Henrich Grežo. 2021. "Cultural Tourism in Nitra, Slovakia: Overview of Current and Future Trends" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 5181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095181

APA StyleKrogmann, A., Ivanič, P., Kramáreková, H., Petrikovičová, L., Petrovič, F., & Grežo, H. (2021). Cultural Tourism in Nitra, Slovakia: Overview of Current and Future Trends. Sustainability, 13(9), 5181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095181