Systemic Innovation Areas for Heritage-Led Rural Regeneration: A Multilevel Repository of Best Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Community Capitals Framework (CCF)

1.2. Systemic Innovation Areas (SIA)

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Selection of the Case Studies

2.2. Data Gathering

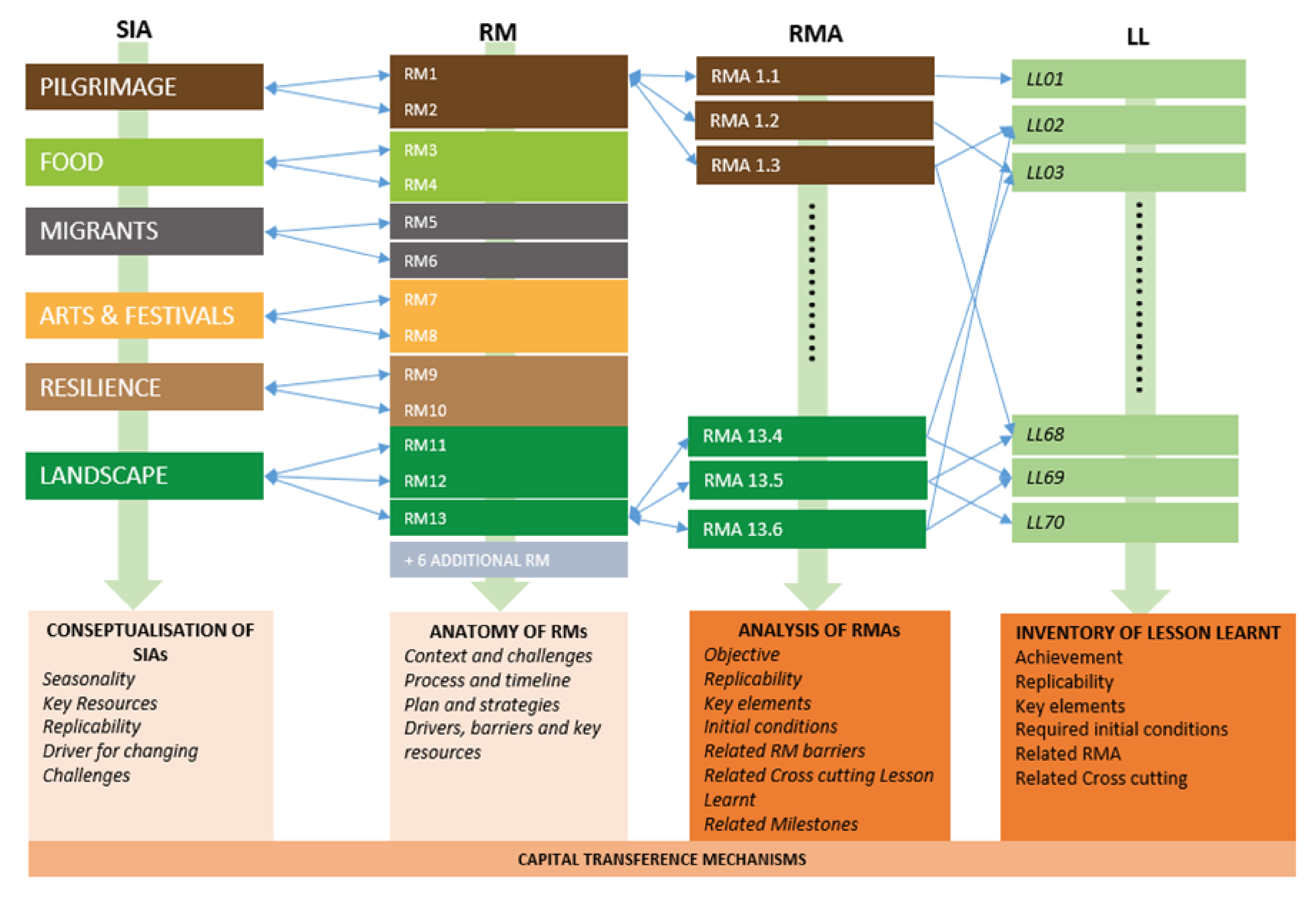

2.3. Levels of Analysis

- General characterisation: includes the seasonality, as a change or pattern in a given period of the year; the key resources needed to build a strategy that capitalises on unique and differentiated cultural and natural resources, the replicability potential and the driver for change, considering that the SIA can be development driven or challenge-driven.

- Challenges: identifies to which challenges (population ageing, immigration, depopulation, unemployment and poverty), the SIA can contribute.

- Capitals: identifies the relevance of each capital in the framework of the SIA, the initial capital needed, the required ones for development by defining general concepts or actions for improvement and the achieved ones, as expected results.

2.4. Building the Repository

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Challenges

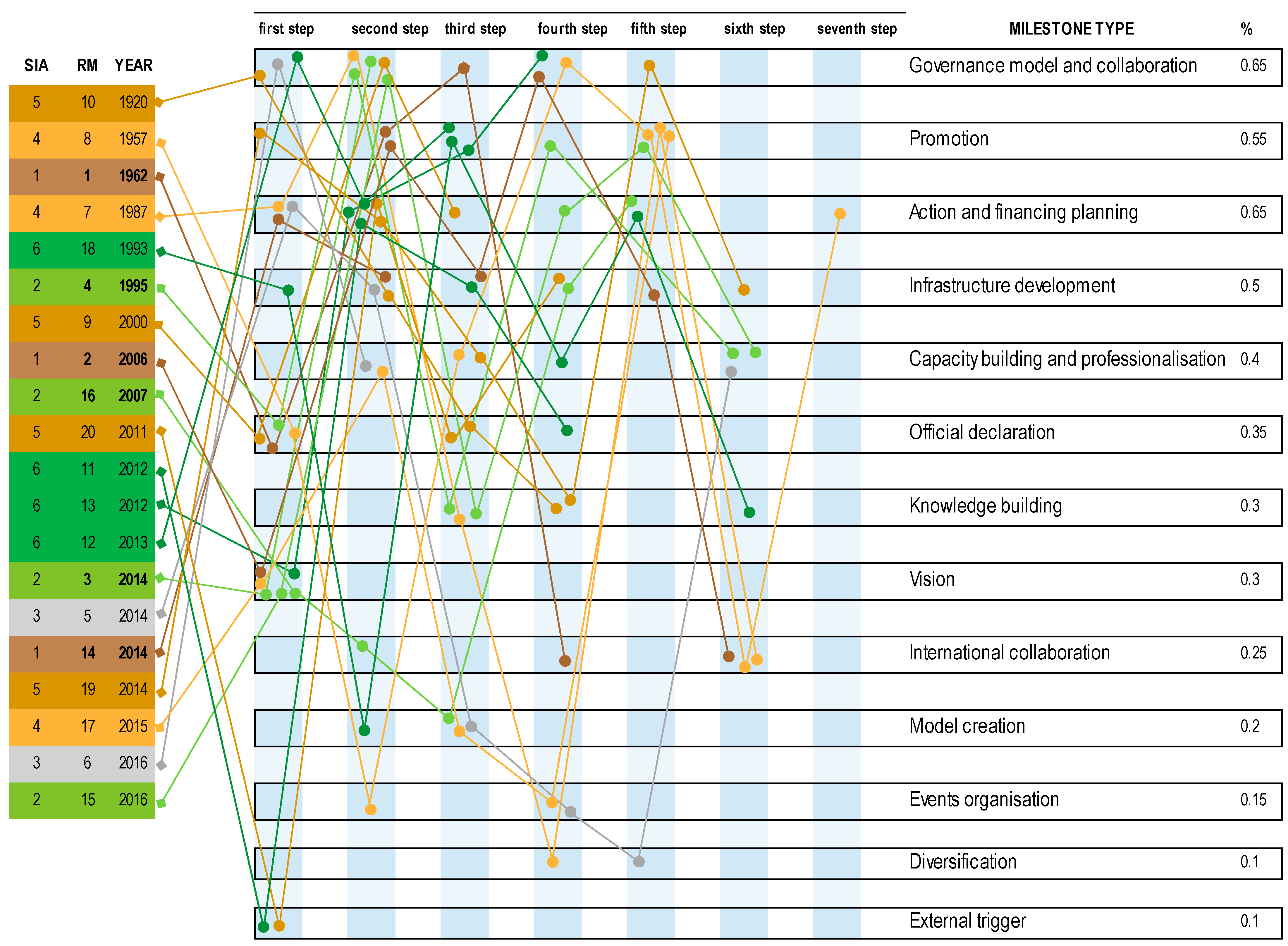

3.2. Process

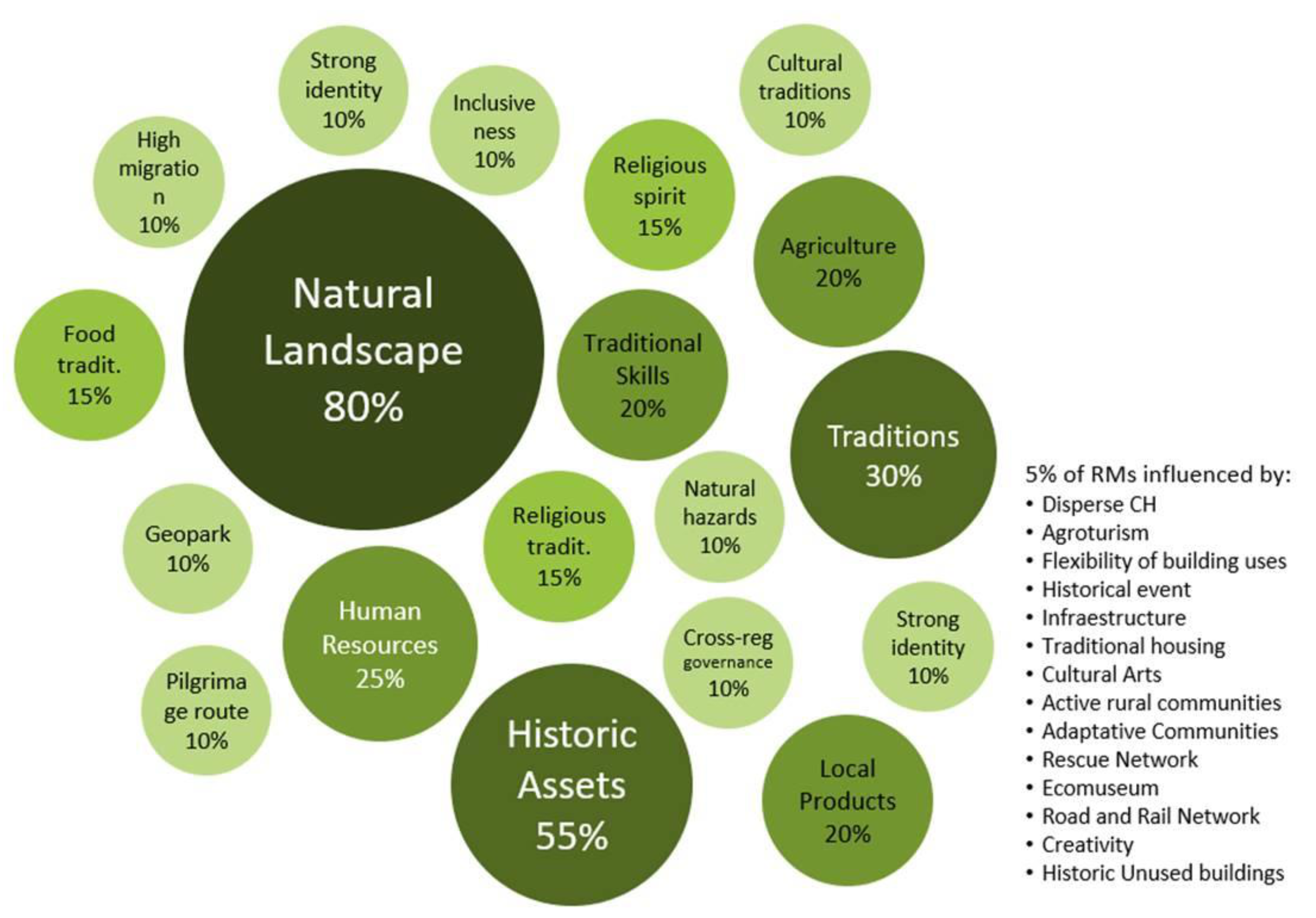

3.3. Key Resources

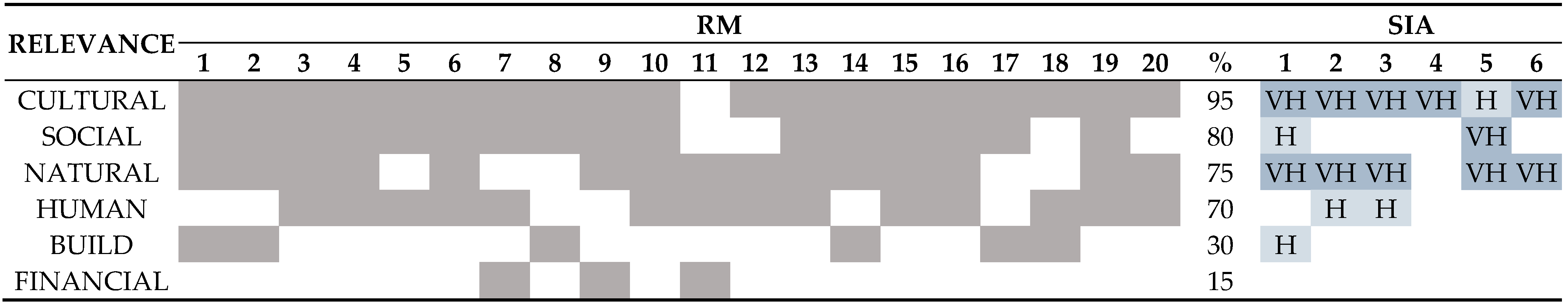

3.4. Conceptualisation of SIAs and Transference of Capitals

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| SIA | SHORT DESCRIPTION | EVIDENCE OF IMPACT |

|---|---|---|

| SIA1 | RM 1—Way of Saint James (Spain) | |

| The French Way is the most traditional path taken for pilgrims (about 60% of pilgrims) running across almost 1000 Km through a territory that possesses more than half of the Spanish heritage | Relevant impact metrics: 270,000 pilgrims from 100 countries; EUR 34 mln yearly income; 5 new brands for local products; 12 fairs; 750,000 people trained. | |

| RM 2—Mary’s way (Romania) | ||

| Although first proposed in 2006, the whole concept of developing and modernising the existing traditional pilgrimage routes into a complex network was developed in 2010. | Relevant impact metrics: 1000 km of routes; 480 km mapped with services; 5000 pilgrims; Festival involving yearly 400 people. | |

| RM 14—Digital Sanctuary (Brasil) | ||

| Estrada Real territory covers 73,000 km2 where several culturally differentiated groups live and have their own forms of social organisation and occupation of the territory and natural resources as a condition for their cultural reproduction. | Relevant impact metrics: 110,000 visitors a year; Network of entities and transforming agents; In the Jubilee year it attracted 14,000 visitors; More than two decades of organising the Festival of Tiradentes | |

| SIA2 | RM 3—Agro-food production in Apulia (Italy) | |

| Traditional economic activity in Apulia is agriculture, but, in recent years, it has developed tourism while managing to preserve old traditions, history and agro-food production; developed new economic activities based on innovation and technology, focused on agro-food production. | Relevant impact metrics: Technological agro-food district involving 100 companies, 12 Research entities, 14 Local administrations, local business; Increased visibility and related products | |

| RM4—Coffee production in WH landscape (Colombia) | ||

| Palestine region is located in the coffee heart of Colombia, with the municipalities of Chinchiná and Manizales form the most important coffee triangle in the department. Coffee represents 68.52% of the municipal area. | Relevant impact metrics: 195,000 tons of coffee produced yearly; 207,000 Ha cultivated within the Coffee Landscape. | |

| RM 15—Agroecological innovations in Trento (Italy) | ||

| The production of high-quality products In Trento is supported by recovering mountain farming practices; environmentally friendly agriculture that ensures preservation and further development of cultural landscapes, safeguard of biodiversity and economic sustainability. | Relevant impact metrics: Creation (2016) of the Operational Group promoting agroecological innovations; Rural Development Plan (2014–2020) for cooperation between farmers and researchers | |

| RM 16—Smart Rural Living Lab, Penela (Portugal) | ||

| Smart Rural Living Lab (SRLL) integrates the low population density area of Penela in a competitive global world. SRLL is a centre of innovation and development for rural sustainability, where agro-food and forestry sectors are the centres of the economic model. | Relevant impact metrics: 10 new companies began labouring in HIESE; Directly created more than 30 jobs; “Excellence SME” growing since 2014 and the territory has one “Gazelle Company”. | |

| SIA3 | RM5—Migrants hospitality and integration in Asti Province (Italy) | |

| The necessity of actions contrasting human trafficking joins here to the local needs, reviving and preserving local agro-food and handcrafts production heritage. Training migrants provides hospitality and avoids emergencies while helping the lack of local resources for maintaining heritage. | Relevant impact metrics: 160 migrants yearly hosted; Creation of an innovative social enterprise for the rehabilitation of old traditional cultivations with organic techniques. | |

| RM6—Boosting migrant integration with nature in Lesvos island (Greece) | ||

| The need to relieve the pressure of the migrants on this island led to the strategy of training and making them collaborate in the local cultural heritage and traditional economic activities’ safeguarding (sheep breeding and olive cultivation). | Relevant impact metrics: 200 migrants yearly trained in NHMLPF; about 6000 migrants yearly hosted in Lesvos (600,000 in 2015) | |

| SIA4 | RM 8—The Living Village of the Middle Age, Visegrad (Hungary) | |

| Visegrád town is embraced by forest-clad hills. From the 1980’s public and private initiatives have launched heritage-based development, targeting tourists. Recently focus changed to developing additional innovations and networking, always aiming to support traditional activities. | Relevant impact metrics: 1000 performers and 40,000 visitors coming per year for the Castle Visegrad Games; Partnerships with 6 other cities in Europe promoting Historical Festivals. | |

| RM 17–Troglodyte village (Tunisia) | ||

| An annual international cinema festival is organised in these troglodyte dwellings dug into the mountains and showcases how the local cultural and natural heritage can be safeguarded, appreciated and interpreted by digital media and art technologies. | Relevant impact metrics: Cinema Festival in Matmata annually organised since 2011; Programs and shows for young audiences; Photography contest and a short film competition in which 120 young people took part | |

| RM7—Take Art: Sustainable Rural Arts Development (United Kingdom) | ||

| Somerset county, traditionally agricultural, started developing a rural touring process in 1986. A long vision strategy (10 years) provided the cultural framework for Take Art to be created. Curiosity and interest from local government offices and authorities helped the process launch. | Relevant impact metrics: Take Art one of the UK’s most celebrated rural touring schemes; Over 750 companies and over 150,000 people; Over 50 art projects; Work with thousands of people, opportunities for all ages. | |

| SIA5 | RM9—Teaching culture for learning resilience in Crete (Greece) | |

| Livestock raising as well as agriculture are the main economic activities in Crete, with growing activities in services and tourism. Psiloritis Geopark was established and, thereinafter, the process of training and teaching culture was launched by the community together with the authorities. | Relevant impact metrics: Resilience training for the community; A toolkit for resilient citizens; Researching the traditional practices to increase resilience; Guidelines for risk assessment and mitigation actions. | |

| RM10—Natural hazards as intangible CNH for human resilience in South-Iceland (Iceland) | ||

| Starting in the sailor’s need of safety, the local community and authorities began to promote participative processes to create a cohesive resilient community. Katla geopark promotes sustainable development and places a strong emphasis on local culture and nature tourism. | Relevant impact metrics: 200,000 overnight stays in Katla each year; 70–100% of local people trained (5% trained as rescue team members); 100% locals and tourists informed in case of the extreme event by SMS. | |

| RM19—Ecomuseum in Alpi Apuane (Italy) | ||

| The Ecomuseum aims at creating a new development model for the Apuan Bioregion through the enhancement of the local heritage; economic alternatives to the monoculture of marble. It is a “pact” between institutions and citizens for territory care. | Relevant impact metrics: Economic benefit and more employment: 40 LPU hired in 2016; Positive impact on the environment and landscape; 3 Municipalities funded for a multi-purpose public vehicle; Increase in visitors. | |

| RM20—Heritage recovery after disaster in Sanriku Fukko National Park (Japan) | ||

| By understanding, utilising and conveying nature, this Build Back Better (BBB) initiative aims to build a resilient culture in Sanriku Fukko (reconstruction) National Park which is a tsunami-prone area in order to minimise the damage by future tsunamis and rapidly revive life in the area. | Relevant impact metrics: Rebuilding (BBB) the park facilities damaged by the tsunami in 2011; “Michinoku Coastal Trail” launched in an area of approximately 1000 km; Monitoring the natural environment | |

| SIA6 | RM 11—A CNH-led approach in Austrått manorial landscape (Norway) | |

| In 2012 a NATO airbase was established in Ørland. Thereinafter, the CNH-led strategy was launched, generating new knowledge on the history and values of the Austrått landscape, conserving and reusing heritage houses, connecting people and formally protecting the area. | Relevant impact metrics: Establishment of an integrated heritage management system; Local business opportunities; Increased tourists and employment related to tourism; Safeguarding the landscape. | |

| RM12—Douro cultural landscape, driver for economic and social development (Spain) | ||

| The diversity of the Douro river basin represents an opportunity and a challenge for its development. Since the creation of AEICE association in 2013, the Duero-Douro has constantly innovated in culture and heritage, joining tourism initiatives for the preservation of the local values. | Relevant impact metrics: 300,000 Ha of Natura2000; 20,000 cultural elements and 1000 historical towns protected; 13 new brands and labels for local products; 110 companies supported; 250 people trained. | |

| RM 13—The Northern Headlands area of Ireland’s Wild Atlantic Way (Ireland) | ||

| It encompasses nine coastal counties of the West of Ireland. In 2012 a Brand Development was carried out; since then the sustainable development implementation has continued, supporting local farmers and producers in the economic regeneration activities. | Relevant impact metrics: 157 discovery points, 1000 attractions and more than 2500 activities; Increased number of tourists in the region; Re-entering of private sector investment in the area. | |

| RM 18—The Halland Model (Sweden) | ||

| An application-oriented theoretical platform with new approaches for building a conservation development. Tailor-made multi-stakeholder networks work in the historic sector together with the labour market, construction industry, property and estate owners and authorities. | Relevant impact metrics: 350 new jobs, 1200 in construction; More than 130 historic buildings saved from demolition; Almost ⅓ of the regions construction workers trained in traditional techniques. | |

Appendix B

| CODE | CAP | R | INITIAL | DEVELOPED | OBTAINED |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM 1 | C | H | UNESCO world heritage site. historic pilgrimage route | national and international recognition | better promotion of cultural resources |

| N | H | natural resources, landscape | protection | integrated natural and cultural values | |

| B | H | high number of religious/historic buildings | infrastructure improved and buildings restored | better safeguarding of built heritage | |

| H | capacity building, increase in pilgrims and social infrastructure | job improvement | |||

| S | H | increased number of associations and society to manage and promote the way | numerous initiatives of civil associations, cohesion from values, revitalisation | ||

| F | increase in investment | official support, promotion, business creation, increase in number of pilgrims | |||

| RM 2 | C | H | historic pilgrimage route | better safeguarding and promotion of cultural heritage | |

| N | H | natural resources, landscape | better safeguarding of natural heritage | ||

| B | H | high number of religious/historic buildings | road network improved | ||

| H | capacity building | job improvement | |||

| S | H | stakeholders collaboration | international stakeholders involvement | networking governance | |

| F | fund raising | increased number of pilgrims and incomes | |||

| RM 14 | C | H | religious traditions | route of pilgrimage development | improved knowledge on the route |

| N | H | high natural value (UNESCO biosphere reserve) | |||

| B | H | historic and religious buildings | buildings restoration | better safeguarding of built heritage | |

| H | capacity building | job improvement | |||

| S | H | network of stakeholders | joint actions for CH valorisation | ||

| F | increased tourism and incomes | ||||

| RM 3 | C | H | traditional gastronomy | promotion and safeguarding of traditions | |

| N | H | natural resources | better safeguarding of natural resources | ||

| B | high number of historic buildings | ||||

| H | H | human resources | capacity building | improved entrepreneurial capabilities | |

| S | H | network of young professional | cooperation between rural and urban citizens | social regeneration of the territory | |

| F | financing by testament | production growth | |||

| RM4 | C | H | coffee culture, UNESCO world heritage site | appreciation and international recognition, festivities | safeguarding of the coffee landscape |

| N | H | biodiversity, landscape | protection and conservation of the coffee cultural landscape and wax palm | better safeguarding of natural landscape, national heritage | |

| B | traditional historic buildings | preservation of architecture | |||

| H | H | high human work in production process | capacity building | job improvement | |

| S | H | articulation of women coffee producers | multi-stakeholder cooperation, women-led rural organisation | producers assisted | |

| F | regeneration of the territory | ||||

| RM 15 | C | H | traditional gastronomy | better safeguarding of farming activities | |

| N | H | high natural value (UNESCO geopark and biosphere reserve; ecomuseum) | agroecological practices implemented | better safeguarding of natural landscape | |

| B | historic assets | avoid infrastructure abandonment | |||

| H | H | cooperative movement and collective property rights | capacity buildings | job improvement | |

| S | H | traditional skills in agriculture | young farmers improved capacity in sustainable mountain livestock system | improved resilience of farms | |

| F | funding | diversification of farms activities to improve provision of ecosystem services | |||

| RM 16 | C | H | latent traditions | improved perception of traditional gastronomy | self-esteem and new opportunities |

| N | H | landscapes and natural resources | new products and services with high value on tourism assets | better safeguarding of natural resources | |

| B | abandoned buildings | reuse | better heritage preservation and new spaces for start-ups | ||

| H | H | human resources | capacity building | creation of new companies and jobs | |

| S | H | open innovation model | new products and services based on rural innovation | ||

| F | incubators and technology transfer, emergence of new services, systems or products | territory as investment opportunity, EU funds | |||

| RM5 | C | H | agriculture, manufacturing, gastronomy traditions | cultural sharing and training on traditional activities | cultural enrichment |

| N | unesco world heritage site (cultural landscape) favorable climate, fields, intact environment | experimentation with different crops, plan of territorial maintenance | hydrogeological risks reduction | ||

| B | abandoned buildings | plan for the restoration of the buildings | hospitality structures for migrants | ||

| H | H | operators with experience on migrants and refugees | catering courses, handcrafted ceramic laboratory, courses on agricultural methods | mixed teams with different profiles | |

| S | H | part of a local consortium | widen possibilities through new partnerships | new collaborations with non profit, profit and public entities | |

| F | funding from public sources | necessity of financing a new kind of expenses | a mix of public and private funds for different activities within the same project | ||

| RM6 | C | H | cultural values, archaeological sites | ||

| N | H | natural resources, landscape, UNESCO site (global geopark) | improved safeguarding of NH | ||

| B | |||||

| H | H | increased number of refugees | educational training and sports activities | migrants’ wellbeing, hazards impact reduction | |

| S | H | social memory: Albanian integrated in the society | volunteers (translators) | migrants’ integration; healthy society | |

| F | humanitarian actions | networking/marketing from other European geoparks | |||

| RM 8 | C | H | historical event | better safeguarding of cultural heritage | |

| N | natural landscape | ||||

| B | H | historic monuments/sites | |||

| H | establishment of enterprises involved in tourism and heritage-led projects; non-profit municipal company foundation | job improvement | |||

| S | H | community participation | citizens’ and participants’ feeling of ownership; international network | citizens involvement, stakeholders engagement | |

| F | financial stability; job creation in the tourism sector | ||||

| RM 17 | C | H | cultural values, identity | valorisation of the public space in all its components | better safeguarding of cultural heritage |

| N | natural resources | ||||

| B | H | traditional underground homes | better safeguarding of traditional living | ||

| H | training of young people on image techniques | improved skills in young people | |||

| S | H | strong amazing identity | acceptance of dissent and freedom of expression improved | more inclusive society | |

| F | increased tourism | ||||

| RM7 | C | H | traditions, national arts policy | rural touring network | innovative cultural offer |

| N | landscape, outdoor settings | outdoor performances | innovative cultural offer | ||

| B | industrial, historic buildings | refurbishment | environmental impact reduction | ||

| H | H | active individuals and groups | mentoring programme for promoters | more confident promoters offering quality arts | |

| S | H | existing social networks | use of networks to promote arts events | provide opportunities and increase confidence | |

| F | H | local community fundraising and national funds | funding strategies | regular, sustained investment | |

| RM9 | C | H | local traditions | promotion and support | new local festivals, events, thematic parks |

| N | H | high natural value, nature2000 | geopark | better safeguarding of natural heritage | |

| B | trails; panels, tools | ||||

| H | local products improvement, people’s resilience improved | job improvement | |||

| S | H | network of companies | geopark products network | ||

| F | H | low finance possibilities, local production | collaborations, branding | geoturism, new funds, more visitors | |

| RM10 | C | H | traditions and storytelling | documentation | pride, resilience |

| N | H | natural resources | natural hazards mitigation; infrastructure | geosites protection | |

| B | vernacular architecture | rebuilding of historic houses; regulation in risk areas | zoning, better structures | ||

| H | H | self-reliance, autarchy | entrepreneurship, innovation, knowledge sharing | initiative, cooperation | |

| S | H | community participation, clusters | cooperation government and community | ||

| F | securing of funds | government funding, tourism | |||

| RM19 | C | H | latent traditions | identification of traditional and sustainable agro-silvo-pastoral and gastronomic activities | better safeguarding of CH |

| N | H | natural resources, landscape | identification of tourism potential for routes recovery | better safeguarding of NH | |

| B | historical settlements and buildings | identification of the l elements as opportunity for sustainable development strategies | better safeguarding of built heritage | ||

| H | H | know-how on traditional mountain economic activities | stakeholders engagement and cooperation | increase job potential, local economy improved | |

| S | H | active local participation and awareness | participatory process | local communities involvement | |

| F | municipalities budget | funding for new projects, local products marketing | public and private calls | ||

| RM20 | C | H | traditions | trail as symbol of reconstruction | deeper knowledge on history and culture |

| N | H | natural resources, landscape | conservation activities, environmental education, land owning | natural environment conserved | |

| B | historic buildings | rebuilding of park facilities, green reconstruction | improved infrastructure | ||

| H | H | learn the experience, better preparation for natural hazards | reactivate agriculture, fishery and forestry | ||

| S | improved sense of belonging | ||||

| F | ecotourism | local revitalisation | |||

| RM 11 | C | cultural values, traditions | recovery of food tradtions | better safeguarding of CH | |

| N | H | natural resources, landscape | Austrått landscape formally protected | better safeguarding of NH, improved natural resources | |

| B | historic buildings | reuse of historic buildings; better connection among places of interests and public facilities | better safeguarding of built heritage | ||

| H | H | airbase human resources | better accessibility | ||

| S | |||||

| F | H | external and national economic resource | |||

| RM12 | C | H | cultural identity, shared values, world heritage sites | designation of origin; protected geographical indications | brand recognition |

| N | H | natural resources, world heritage sites | natural heritage as a resource | ||

| B | disperse heritage buildings, world heritage sites | action plan | historic buildings preserved | ||

| H | H | entities working on cultural heritage | creation of an association; collaborative work; strategic plan | improve professional practice | |

| S | alliance between wine tourism and heritage | participatory mechanisms | |||

| F | revitalisation of the ch sector; creation of new business models | ||||

| RM 13 | C | H | strong traditions | traditions revival | high quality visitors experiences, cultural tourism |

| N | H | natural resources, UNESCO global geopark | food strategies, discovery points and signature points | ||

| B | heritage buildings | improved infrastructure and access | |||

| H | H | local enterprises food, textile and marine sector | increased capabilities for enterprises | increase job potential | |

| S | H | stakeholders collaboration | strategies for development | ||

| F | more investment | improved tourism products, increased number of visitors | |||

| RM 18 | C | H | cultural activities and traditional skills | traditional building techniques maintained, cultural centres | |

| N | environmentally friendly activities | improved environment | |||

| B | H | historic buildings at risk | improved premises to host cultural activities, adaptive reuse; creative industries | historic buildings preserved | |

| H | H | traditional skills | high level of craftsmanship; business contributing to development | new business opportunities | |

| S | training programmes, cooperation | ensure stable labour market | |||

| F | national investment among different sectors | CH budget increased, increased tourism, growth of the construction sector |

References

- UN General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 56350, A/Res/70/1. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Getting Cultural Heritage to Work for Europe: Report of the Horizon 2020 Expert Group on Cultural Heritage; European Union: Luxembourg, 2015; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, J. The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability: Culture’s Essential Role in Public Planning; Common Ground Publishing: Champaign, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nurse, K. Culture as the fourth pillar of sustainable development. Small States Econ. Rev. Basic Stat. 2006, 11, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, F. Culture as Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development: Perspectives for Integration, Paradigms of Action. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L. Multidimensional Assessment for “Culture-Led” and “Community-Driven” Urban Regeneration as Driver for Trigger Economic Vitality in Urban Historic Centers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinardi, C. Unsettling the role of culture as panacea: The politics of culture-led urban regeneration in Buenos Aires. City Cult. Soc. 2015, 6, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysgård, H.K. The ‘actually existing’ cultural policy and culture-led strategies of rural places and small towns. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.; Jayne, M. The creative countryside: Policy and practice in the UK rural cultural economy. J. Rural Stud. 2010, 26, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysgård, H.K. The assemblage of culture-led policies in small towns and rural communities. Geoforum 2019, 101, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S. Small city–big ideas: Culture-led regeneration and the consumption of place. In Small Cities; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, C.; McGehee, N.; Delconte, J. Built Capital as a Catalyst for Community-Based Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahramani, L.; McArdle, K.; Fatorić, S. Minority Community Resilience and Cultural Heritage Preservation: A Case Study of the Gullah Geechee Community. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubiaga, M.; Izkara, J.L.; Gandini, A.; Alonso, I.; Saralegui, U. Towards Smarter Management of Overtourism in Historic Centres Through Visitor-Flow Monitoring. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Tunbridge, J.E. Multiple approaches to heritage in urban regeneration: The case of City Gate, Valletta. J. Urban. Des. 2016, 22, 494–501. [Google Scholar]

- Dogruyol, K.; Aziz, Z.; Arayici, Y. Eye of Sustainable Planning: A Conceptual Heritage-Led Urban Regeneration Planning Framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Good Practices at FAO: Experience Capitalization for Continuous Learning. 2013. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ap784e/ap784e.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Tan, Y.; Xu, H.; Jiao, L.; Ochoa, J.J.; Shen, L. A study of best practices in promoting sustainable urbanization in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 193, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowicz, S.G.; Chinapah, V. Good Practices in Pursuit of Sustainable Rural Transformation. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 4, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Emery, M.; Flora, C. Spiraling-Up: Mapping Community Transformation with Community Capitals Framework. Community Dev. 2006, 37, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulcak, F.; Haider, J.L.; Abson, D.J.; Newig, J.; Fischer, J. Applying a capitals approach to understand rural development traps: A case study from post-socialist Romania. Land Use Policy 2015, 43, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capello, R.; Caragliu, A.; Nijkamp, P. Territorial Capital and Regional Growth: Increasing Returns in Cognitive Knowledge Use; Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Terluin, I.J. Differences in economic development in rural regions of advanced countries: An overview and critical analysis of theories. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, R.S.; Lück, M.; Schänzel, H.A. A conceptual framework of tourism social entrepreneurship for sustainable community development. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 37, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Straub, A.M.; Gray, B.J.; Ritchie, L.A.; Gill, D.A. Cultivating disaster resilience in rural Oklahoma: Community disenfranchisement and relational aspects of social capital. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 73, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwasu, M.; Fuchigami, Y.; Ohno, T.; Takeda, H.; Kurimoto, S. On the valuation of community resources: The case of a rural area in Japan. Environ. Dev. 2018, 26, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, V.; de los Rios, I.; Cruz-Collaguazo, E.; Coronel-Becerra, J. Analysis of available capitals in agricultural systems in rural communities: The case of Saraguro, Ecuador. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 4, 1191–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, R.; Oikarinen, L.; Simpson, H.; Michaelson, M.; Gonzalez, M.S. Boom, Bust and Beyond: Arts and Sustainability in Calumet, Michigan. Sustainability 2016, 8, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, C.B. Social capital and community problem solving: Combining local and scientific knowledge to fight invasive species. In: Falk, I.; Surrata, K.; Suwondo, K. (orgs.). Community Management of Biosecurity, Special Copublication. Indonesia: Journal of Interdisciplinary Development Studies; Australia: Learning Communities International Journal of Learning in Social Contexts, 2008. pp. 30–39. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10919/67672 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Svendsen, G.; Sørensen, J.F.L. The socioeconomic power of social capital: A double test of Putnam’s civic society argument. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2006, 26, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. The New Rural Paradigm: Policies and Governance; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Balestrieri, M.; Congiu, T. Rediscovering rural territories by means of religious route planning. Sustainability 2017, 9, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, M.L.; Nolan, S. Religious sites as tourism attractions in Europe. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleere, H. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society, 2005. 2020. Available online: https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-3-030-30018-0_1051 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Sims, R. Food, place and authenticity: Local food and the sustainable tourism experience. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.E.; de Hoyos, M.; Jones, P.; Owen, D. Rural Development and Labour Supply Challenges in the UK: The Role of Non-UK Migrants. Reg. Stud. 2009, 43, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conticelli, E.; de Luca, C.; Egusquiza, A.; Santangelo, A.; Tondelli, S. Inclusion of migrants for rural regeneration through cultural and natural heritage valorization. INPUT Acad. Plan. Nat. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019. Available online: https://www.ruritage.eu/wpcontent/uploads/fvcontest/c1/Deliverables/Publications/FinalpublicationConticellietal.pdf?_t=1599656569 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Conticelli, E.; de Luca, C.; Santangelo, A.; Tondelli, S. From urban to rural creativity. How the ‘creative city’ approach is transposed in rural communities. In The Global City. The Urban Condition as a Pervasive Phenomenon; Pretellii, M., Tamborrino, R., Tolic, I., Eds.; AISU: Torino, Italy, 2020; Insights, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannini, E.; Benczur, P.; Campolongo, F.; Cariboni, J.; Manca, A.R. Time for Transformative Resilience: The COVID-19 Emergency; JRC Working Papers: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Secretariat of the Council of Europe Landscape Convention. Landscape Convention -Contribution to Human Rights, Democracy and Sustainable Development; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, C.; Tondelli, S.; Åberg, H. The Covid-19 pandemic effects in rural areas. TeMA-J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2020. Available online: http://www.tema.unina.it/index.php/tema/article/view/6844 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Veselý, A. Arnošt Veselý: Theory and Methodology of Best Practice Research: A Critical Review of the Current State. Cent. Eur. J. Public Policy 2011, 5, 98–117. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, H.; Birks, M.; Franklin, R.; Mills, J. Case study research: Foundations and methodological orientations. Forum Qual. Soz. 2017. Available online: https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/2655 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Council of Europe. A better future for Europe´s rural areas. In Congress of Local and Regional Authorities; 2017; Available online: https://rm.coe.int/a-better-future-for-europe-s-rural-areas-governance-committee-rapporte/168074b728 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Neumeier, S. Social innovation in rural development: Identifying the key factors of success. Geogr. J. 2017, 183, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Why some rural areas decline while some others not: An overview of rural evolution in the world. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, K. What makes a successful rural regeneration partnership? The views of successful partners and the importance of ethos for the community development professional. Community Dev. 2012, 43, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisbuch, G. Urban exodus and the dynamics of COVID-19 pandemics. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2021, 569, 125780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Travel Tourism Council; Wyman, O. To Recovery Beyond: The Future of Travel Tourism in the Wake of COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2020/To%20Recovery%20and%20Beyond-The%20Future%20of%20Travel%20Tourism%20in%20the%20Wake%20of%20COVID-19.pdf?ver=2021-02-25-183120-543 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

| Capitals | Definitons by [30] | Ruritage Approach |

|---|---|---|

| CULTURAL CAPITAL | Cultural capital reflects the way people “know the world” and how they act within it, as well as their traditions and language. Cultural capital influences how creativity, innovation, and influence emerge and are nurtured. | In the RURITAGE context, intangible heritage and rural traditions are some of the key assets included in this capital that the project aims to capitalise on. |

| NATURAL CAPITAL | Natural capital refers to those assets that reside in a location, including weather, geographic isolation, natural resources, amenities, and natural beauty. Natural capital shapes the cultural capital connected to a place. | Natural Capital connected with biodiversity and landscape is one of the key assets that rural destinations traditionally take advantage of. |

| BUILT CAPITAL | Built capital refers to housing, transportation infrastructure, telecommunications infrastructure and hardware, utilities, heritage buildings and infrastructure. | Historic built heritage can play a key role in the heritage-led process if it is reused and maintained from a sustainability perspective. |

| SOCIAL CAPITAL | Social capital reflects the connections among people and organisations or the social “glue” to make things, positive or negative, happen. Bonding social capital refers to those close redundant ties that build community cohesion. Bridging social capital involves loose ties that bridge among organisations and communities. Political capital is included here and reflects access to power and to organisations and connection to resources and power brokers. Governance and political capital is included here as the ability of people to find their own voice and to engage in actions that contribute to the well-being and development of their community. | In RURITAGE, social capital is understood as the capacity of the community to build sustainable economic development networks, local mobilisation of resources, and willingness to consider alternative ways of reaching goals. Community resilience is considered among the most crucial characteristics of social capital and it is built through the development of local participatory approaches. |

| HUMAN CAPITAL | Human capital is understood to include the skills and abilities of people to develop and enhance their resources and to access outside resources and bodies of knowledge to increase their understanding, identify promising practices, and access data for community-building. | In RURITAGE, human capital refers to the peculiar skills and abilities coming from rural traditions and context, and it is improved through practices that contribute to the health, training and education of the population. It is strictly linked to building local capacity linked to job and income diversification to support re-population processes. |

| FINANCIAL CAPITAL | Financial capital refers to the financial resources available to invest in community capacity-building, to underwrite the development of businesses, to support civic and social entrepreneurship, and to accumulate wealth for future community development. | In RURITAGE, the financial capital is understood as a means to achieve the growth of the other capitals supporting civic and social entrepreneurship and to accumulate wealth for future community development. |

| SIA | CODE | NAME | COUNTRY |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIA1 | RM 1 | Way of Saint James | Spain |

| RM 2 | Mary’s way | Romania | |

| RM 14 | Digital Sanctuary | Brasil | |

| SIA2 | RM 3 | Agro-food production in Apulia | Italy |

| RM4 | Coffee production in WH landscape | Colombia | |

| RM 15 | Agroecological innovations in Trento | Italy | |

| RM 16 | Smart Rural Living Lab, Penela | Portugal | |

| SIA3 | RM5 | Migrants hospitality and integration in Asti Province | Italy |

| RM6 | Boosting migrant integration with nature in Lesvos island | Greece | |

| SIA4 | RM 8 | The Living Village of the Middle Age, Visegrad | Hungary |

| RM 17 | Troglodyte village | Tunisia | |

| RM7 | Take Art: Sustainable Rural Arts Development | United Kingdom | |

| SIA5 | RM9 | Teaching culture for learning resilience in Crete | Greece |

| RM10 | Natural hazards as intangible CNH for human resilience in South-Iceland | Iceland | |

| RM19 | Ecomuseum in Alpi Apuane | Italy | |

| RM20 | Heritage recovery after disaster in Sanriku Fukko National Park | Japan | |

| SIA6 | RM 11 | A CNH-led approach in Austrått manorial landscape | Norway |

| RM12 | Douro cultural landscape, driver for economic and social development | Spain | |

| RM 13 | The Northern Headlands area of Ireland’s Wild Atlantic Way | Ireland | |

| RM 18 | The Halland Model | Sweden |

| Campaign | Dates | Objectives | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summer campaign | July 2018–November 2018 | Identification of best practices and their relevance. Context of the RM that included administrative, geographical, demography and transportation information. Narrative of the regeneration process (key factors, timeline and actors). Heritage and non-heritage resources. | Spreadsheets sent to the RM case studies |

| Autumn campaign | November 2018–January 2019 | Validation of Summer campaign results and identify and define the role and function of cross-cutting themes. | Spreadsheets sent to the RM case studies |

| Winter campaign | February 2019–June 2019 | Fill the information gaps identified to complete the analysis from the Practices Repository and to further identify the key success factors for heritage-led rural regeneration in the sites | Targeted: bilateral validations and project workshops (Valladolid 19–22 March and Crete 28–30 May) |

| Levels | Characterisation | Process | Keywords | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIA | replicability | key resources | challenges | driver for changing | seasonal | capital transference mechanism | keywords | ||||

| development | relevance | ||||||||||

| challenge | initial | ||||||||||

| developed | |||||||||||

| obtained | |||||||||||

| RM | replicability | key resources | challenges | drivers | context | capital transference mechanism | knowledge building | barriers | co-benefits | process | keywords |

| ageing of the population | geography | initial | milestone | ||||||||

| immigrants | main economic sector | developed | year | ||||||||

| depopulation | size of influence | obtained | conceptual step | ||||||||

| unemployment | |||||||||||

| poverty | |||||||||||

| RMA | replicability | key elements | objectives | initial conditions | related capital | capital transference mechanism | keywords | ||||

| financial | |||||||||||

| social | |||||||||||

| built | |||||||||||

| natural | |||||||||||

| cultural | |||||||||||

| human | |||||||||||

| COLOUR CODE | FREE TEXT | ||||||||||

| CATEGORIES | |||||||||||

| BOTH | |||||||||||

| KEYWORDS | |||||||||||

| RM | SIA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHALLENGE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| POPULATION AGEING | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| IMMIGRANTS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DEPOPULATION | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UNEMPLOYMENT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| POVERTY | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SIA 1 Pilgrimage | SIA 2 Sustainable Local Food | SIA 3 Migration | SIA 4 Art and festivals | SIA 5 Resilience | SIA 6 Landscape Management | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEASONALITY | Medium | Depends on the food | Low | High | Low | Low |

| REPLICABILITY | Medium-low | High | Medium-high | High | Medium-high | Medium |

| DRIVER | Development | Development | Challenge | Development | Challenge | Development |

| KEY RESOURCES |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Code | Rel. | Initial | Developed | Achieved | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIA 1 | C | VH | religious | broad dissemination of the CH | |

| N | VH | landscape | broad dissemination of the NH | ||

| B | H | disperse building CH | tourism/transport infrastructure | improvement of built CH | |

| H | capacity building | better jobs | |||

| S | H | cross-region governance | networking governance | ||

| F | jobs and business opportunities through tourism | ||||

| SIA2 | C | VH | gastronomy | broad dissemination of the CH (gastronomy) | |

| N | VH | local products | sustainable agriculture | ||

| B | hostelry infrastructure | ||||

| H | H | capacity building | better jobs | ||

| S | collaboration | ||||

| F | jobs through services and industry | ||||

| SIA3 | C | H | diverse CH | cultural enrichment | |

| N | diverse NH | improved safeguarding of NH | |||

| B | hospitality structures for migrants | Improvements of CH buildings | |||

| H | H | migrants | capacity building | migrants well being | |

| S | H | social memory | volunteering, collaboration | social inclusiveness | |

| F | business and jobs opportunities | ||||

| SIA4 | C | VH | intangible | cultural enrichment (arts) | |

| N | |||||

| B | infrastructure for the events | new infrastructures/ CH restoration | |||

| H | human resources for the events | better jobs | |||

| S | management | ||||

| F | job/business opportunities | ||||

| SIA5 | C | H | recompilation of local knowledge | better safeguarding of CH | |

| N | VH | landscape | better safeguarding of NH | ||

| B | risk knowledge | better safeguarding of built heritage | |||

| H | safer conditions | ||||

| S | VH | stakeholder cooperation | |||

| F | economic development of the area | ||||

| SIA 6 | C | VH | cultural landscape | CH conservation | |

| N | VH | natural landscape | NH conservation | ||

| B | knowledge building | ||||

| H | training | better jobs | |||

| S | collaboration between stakeholders | networking governance | |||

| F | business and jobs opportunities through tourism |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Egusquiza, A.; Zubiaga, M.; Gandini, A.; de Luca, C.; Tondelli, S. Systemic Innovation Areas for Heritage-Led Rural Regeneration: A Multilevel Repository of Best Practices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095069

Egusquiza A, Zubiaga M, Gandini A, de Luca C, Tondelli S. Systemic Innovation Areas for Heritage-Led Rural Regeneration: A Multilevel Repository of Best Practices. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):5069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095069

Chicago/Turabian StyleEgusquiza, Aitziber, Mikel Zubiaga, Alessandra Gandini, Claudia de Luca, and Simona Tondelli. 2021. "Systemic Innovation Areas for Heritage-Led Rural Regeneration: A Multilevel Repository of Best Practices" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 5069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095069

APA StyleEgusquiza, A., Zubiaga, M., Gandini, A., de Luca, C., & Tondelli, S. (2021). Systemic Innovation Areas for Heritage-Led Rural Regeneration: A Multilevel Repository of Best Practices. Sustainability, 13(9), 5069. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095069