The Role of Commitment in the Relationship between Components of Organizational Culture and Intention to Stay

Abstract

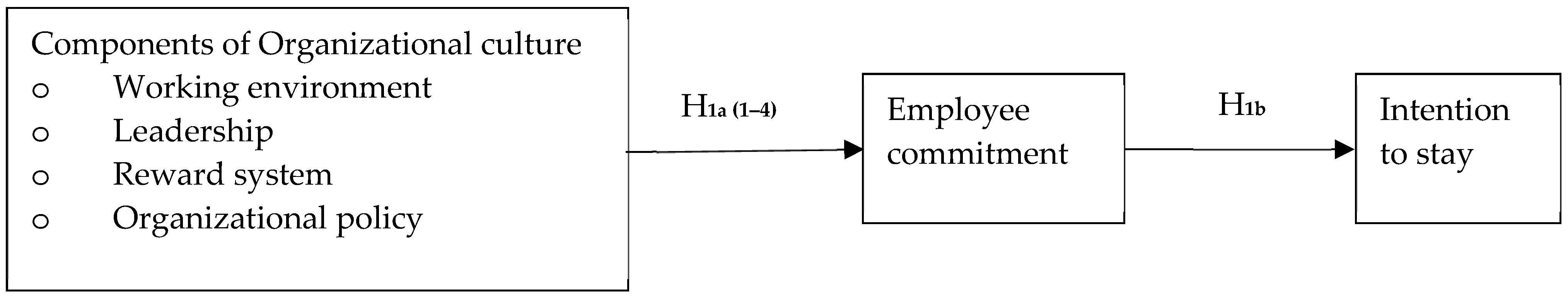

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Institutional Sustainability

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.3. Leadership and Employee Retention

2.4. Work Environment and Employee Retention

2.5. Reward and Recognition

2.6. Organizational Policy

2.7. Hypotheses

3. Method

3.1. Data Source and Measurement

3.2. Ethical Approval

3.3. Variables Measured

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Assessment of the Measures

4.2. Reliability and Validity of the Constructs

4.3. Common Method Bias Assessment

4.4. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

4.5. Assessment of Hypotheses

4.6. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nohria, N.; Groysberg, B.; Lee, L.E. Employee motivation: A powerful new model. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 3, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar, J. Talent management strategy of employee engagement in Indian ITES employees: Key to retention. Empl. Relat. 2007, 29, 640–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, B.; Helfrich, D.; Gretczko, M.; Schwartz, J. Human Capital Trends 2012: Leap Ahead; Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu India Private Ltd.: Mumbai, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, H.J.; Molloy, J.C.; Cooper, J.T. Conceptual foundations: Construct definitions and theoretical representations of workplace commitments. In Commitment in Organizations: Accumulated Wisdom and New Directions; Klein, H.J., Becker, T.E., Meyer, J.P., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group: Florence, KY, USA, 2009; pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Benkarim, A.; Imbeau, D. Organizational Commitment and Lean Sustainability: Literature Review and Directions for Future Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, J.E.; Zajac, D.M. A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Becker, T.E.; Van Dick, R. Social identities and commitments at work: Toward an integrative model. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Herscovitch, L. Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2001, 11, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.E. Foci and bases of commitment: Are they distinctions worth making? Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberghe, C. Organizational commitments. In Commitment in Organizations: Accumulated Wisdom and New Directions; Klein, H.J., Becker, T.E., Meyer, J.P., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group: Florence, KY, USA, 2009; pp. 99–135. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, T.E. Interpersonal commitments. In Commitment in Organizations: Accumulated Wisdom and New Directions; Klein, H.J., Becker, T.E., Meyer, J.P., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group: Florence, KY, USA, 2009; pp. 137–178. [Google Scholar]

- Neubert, M.J.; Wu, C. Action commitments. In Commitment in Organizations: Accumulated Wisdom and New Directions; Klein, H.J., Becker, T.E., Meyer, J.P., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group: Florence, KY, USA, 2009; pp. 179–213. [Google Scholar]

- Deal, T.E.; Kennedy, A.A. The New Corporate Cultures: Revitalizing the Workplace after Downsizing, Mergers, and Reengineering; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter, J.P. Corporate Culture and Performance; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Martinez-Canas, R.; Fontrodona, J. Ethical culture and employee outcomes: The mediating role of person-organization fit. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroufe, R. Integration and organizational change towards sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galpin, T.; Lee Whittington, J. Sustainability leadership: From strategy to results. J. Bus. Strategy 2012, 33, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee green behaviour: A theoretical framework, multilevel review, and future research agenda. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.; Jackson, S.E.; Ployhart, R.E. Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, M.; Tomic, W. A review of creativity within organizations from a psychological perspective. J. Manag. Dev. 2010, 29, 322–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, G.; Steele, G. Organizational commitment: A study of managers in hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2003, 15, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Shahzad, N.; Sheikh, Q.; Batool, S.; Riaz, M.; Saddique, S. Variables that Have an Impact on Employee Satisfaction and Turnover Intention. Int. J. Res. Commer. Econ. Manag. 2013, 3, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, M.; Wang, J.; Long, R. A Comprehensive Model of the Relationship between Miners’ Work Commitment, Cultural Emotion and Unemployment Risk Perception. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.C.; Baker, T.; Hunt, T.G. Values and person-organization fit: Does moral intensity strengthen outcomes? Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2011, 32, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, S.; Godkin, L.; Lucero, M. Ethical context, organizational commitment, and person-organization fit. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 41, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smircich, L. Concepts of culture and organizational analysis. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M. Understanding Organizational Culture; Sage: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E.; Quinn, R.E. Organizational change and development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1999, 50, 361–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sackmann, S.A. Culture and performance. Handb. Organ. Cult. Clim. 2011, 2, 188–224. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkanasy, N.M.; Wilderom, C.P.M.; Peterson, M.F. (Eds.) Handbook of Organizational Culture and Climate; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B.; Ehrhart, M.G.; Macey, W.H. Organizational Climate and Culture. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, M.S. Universal moral values for corporate codes of ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 59, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, H.S., Jr. Reinforcing ethical decision making through organizational structure. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 28, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Trevino, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership Theory and Practice, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Trevino, L.K.; Nelson, K.A. Managing Business Ethics, 5th ed.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, J.; Slocum, J.W., Jr. Managing corporate culture through reward systems. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2005, 19, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Fasolo, P.; Davis-LaMastro, V. Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Callanan, G.A. Career Management; The Dryden Press: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McNeese-Smith, D. Job Satisfaction, Productivity, and Organizational Commitment. J. Nurse Assoc. 1995, 25, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunetto, Y.; Farr-Wharton, R. Using social identity theory to explain the job satisfaction of public sector employees. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2002, 15, 534–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.H.; Chang, S.T.; Chen, G.L. Applying Structural Equation Model to Study of the Relationship Model among leadership style, satisfaction, Organization commitment and Performance in hospital industry. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on E-Business and Information System Security, Wuhan, China, 23–24 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berta, W.; Laporte, A.; Valdmanis, V.G. Observations on institutional long-term care in Ontario: 1996-2002. Can. J. Aging/La Rev. Can. Vieil. 2005, 24, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silbert, L.T. The Effect of Tangible Rewards on Perceived Organizational Support. Management Sciences. 2005. Available online: uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstream/10012/872/1 (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Freyermuth. Retaining Employees in a Tightening Labor Market, RSM McGladrey. 2007. Available online: www.cfo.com/whitepapers/index.cfm/displaywhitepaper/10308654 (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Miller, N.; Erickson, A.; Yust, B. Sense of place in the workplace: The relationship between personal objects and job satisfaction and motivation. J. Inter. Des. 2001, 27, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeytinoglu, I.U.; Denton, M. Satisfied Workers, Retained Workers: Effects of Work and Work Environment on Homecare Workers: Job Satisfaction, Stress, Physical Health, and Retention; CHSRF FCRSS—Candanian Health Services Research Foundation, Foundation Canadienne de la Recherché sur les Services de Sante: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, M.; Thelen, L. What does your workspace say about you? The influence of personality, status and workspace on personalization. Environ. Behav. 2002, 3, 300–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hytter, A. Dark Side Leaders, Work Environment and Employee Health. Retrieved from Växjö University, Studies in Leadership, Entrepreneurship, and Organization. 2008. Available online: hvxu.se/ehv/forskning/hofreseminarier/2008/080514%20DarkSide%20Final (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Normann, R. Service Management. Strategy and Leadership in Service Business; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, J.W. Perspectives. Hum. Resour. Plan. 2001, 24, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, J.; Chan, C.C. Human resource practices, organizational commitment and intention to stay. Int. J. Manpow. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P. High Performance Workplaces: The Role of Employee Involvement in a Modern Economy. 2002. Available online: www.berr.gov.uk/files/file26555.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Noah, Y. A Study of Worker Participation in Management Decision Making Within Selected Establishments in Lagos, Nigeria. J. Soc. Sci. 2008, 17, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J.; Porter, C.O.L.H.; Ng, K.Y. Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Colwell, K.A. Employee reactions to unfair outcomes in the workplace: The contributions of Adams’s equity theory to understanding work motivation. In Motivation and Work Behavior, 7th ed.; Steers, R.M., Porter, L.W., Eds.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jeevananda, S. A study on customer satisfaction level at Hypermarkets in Indian Retail Industry. Res. J. Soc. Sci. Manag. 2011, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; Ahmad, B.; Farihah, N.A.; Haron, H. The Effect of Employees’ Perceived Fairness of Performance Appraisal Systems on Employees’ Organizational Commitment. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 448–465. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavior research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Cote, J.A.; Buckley, M.R. Lack of method variance in self-reported affect and perceptions at work: Reality or artifact? J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Hoffman, J.M.; West, S.G.; Sheets, V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletzer, J.L.; Bentvelzen, M.; Oostrom, J.K.; de Vries, R.E. A meta-analysis of the relations between personality and workplace deviance: Big Five versus HEXACO. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 112, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, S.; Khan, M.I. The effects of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behaviour: Moderation of proactive personality. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2019, 9, 8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvaux, E.; Meeussen, L.; Mesquita, B. Emotions are not always contagious: Longitudinal spreading of self-pride and group pride in homogeneous and status-differentiated groups. Cogn. Emot. 2015, 30, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverthorne, C. The impact of organizational culture and person-organization fit on organizational commitment and job satisfaction in Taiwan. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2004, 25, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appealbaoum, S.; Bartolomucii, N.; Beaumier, E.; Boulanger, J.; Corrigan r Dore, I.; Girard, C.; Serroni, C. Organizational Citizenship behaviour a case study of culture, leadership and trust. Manag. Decis. 2004, 42, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfes, K.; Shantz, A.D.; Truss, C.; Soane, E.C. The link between perceived human resource management practices, engagement and employee behaviour: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stratum | Population | Sample | Response | Response % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching | 314 | 157 | 143 | 91.1 |

| Non-Teaching | 160 | 80 | 73 | 91.3 |

| Total | 474 | 237 | 216 | 91.1 |

| Item | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 153 | 70.8 |

| Female | 63 | 29.2 | |

| Age | 25–35 years | 43 | 19.9 |

| 36–45 years | 98 | 45.4 | |

| 46–55 years | 70 | 32.4 | |

| 56–60 years and above | 5 | 2.3 | |

| Staff Category | Academic | 143 | 66.2 |

| Non-Academic | 73 | 33.8 | |

| Number of years worked in this institution | Below 1 year | 13 | 6.0 |

| Between 2–5 years | 89 | 41.2 | |

| Between 6–10 years | 105 | 48.6 | |

| Above 10 years | 9 | 4.2 | |

| Total | 216 | 100.0 | |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reward system | ||||||

| 2 | Organizational policy | 0.397 ** | |||||

| 3 | Work environment | 0.362 ** | 0.551 ** | ||||

| 4 | Leadership | 0.393 ** | 0.483 ** | 0.335 ** | |||

| 5 | Employee commitment | 0.533 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.540 ** | 0.595 ** | ||

| 6 | Intention to stay | 0.420 ** | 0.384 ** | 0.422 ** | 0.331 ** | 0.519 ** | – |

| Construct/Indicators/Validity and Reliability Results | Loadings (T-Values) |

|---|---|

| Reward system (CA = 0.744; CR = 0.759; AVE = 0.517) | |

| - Staff are positively recognized when they come up with high-quality work | 0.843 (6.86) † |

| - The university pays a better reward package compared to other similar organizations | 0.634 (fixed) |

| - The university cherishes individual excellence over teamwork | 0.662 (6.26) |

| Organisational policy (CA = 0.871; CR = 0.872; AVE = 0.629) | |

| - Policies and procedures of the university have been helpful | 0.826 (9.99) |

| - Progress procedures for monitoring the planned objectives of the university are reviewed periodically | 0.765 (fixed) |

| - The current university management structure promotes our way of doing things | 0.817 (9.88) |

| - This university has a definite vision/mission to guide its goals and aspirations | 0.763 (9.17) |

| Work environment (CA = 0.839; CR = 0.841; AVE = 0.572) | |

| - There is a balance between my working life and my family life | 0.797 (fixed) |

| - In all, I see this university as a peaceful place of work | 0.782 (9.56) |

| - Welfare of staff is regarded as the number one priority of the university | 0.803 (9.83) |

| - As per my core task, the immediate physical working conditions are sufficient | 0.630 (7.49) |

| Leadership (CA = 0.786; CR = 0.797; AVE = 0.568) | |

| - The leadership practices in this university propel me to become a high performing staff | 0.807 (fixed) |

| - Leadership practices of this university are consistent with my personal values | 0.733 (8.27) |

| - Staff of this university are well-informed on issues that are deemed very important to them | 0.718 (8.12) |

| Employee commitment (CA = 0.910; CR = 0.929; AVE = 0.668) | |

| - I have a strong feeling of belonging at this university | 0.792 (10.99) |

| - I am very ready to give my all to help this university succeed | 0.822 (fixed) |

| - I am always eager to let people know that I am part of this university | 0.875 (12.63) |

| - I am always concerned about the future of this University | 0.806 (11.20) |

| Intention to stay (CA = 0.866; CR = 0.870; AVE = 0.628) | |

| - I plan to work at my present job for as long as possible | 0.689 (9.40) |

| - I am most certainly going to look for a new job in the very near future † | 0.891 (fixed) |

| - I plan to stay in this job for at least two to three years | 0.868 (13.20) |

| - I would not like to quit this job | 0.701 (9.65) |

| MODEL | χ2 (DF) | χ2/DF | ∆ χ2 | ∆DF | RMSEA | NNFI | CFI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline model (b) | 292.07 (219) | 1.334 | – | 0.048 | 0.925 | 0.935 | 0.063 | |

| Model 1 | 370.94 (220) | 1.686 | ∆ χ2 (b, m1) = 78.82 * | 1 | 0.069 | 0.853 | 0.872 | 0.233 |

| Model 2 | 288.47 (215) | 1.342 | ∆ χ2 (b, m2) = 3.6 | 4 | 0.049 | 0.926 | 0.937 | 0.058 |

| Model 3 | 363.74 (219) | 1.661 | ∆ χ2 (m2, m3) = 75.27 * | 4 | 0.068 | 0.857 | 0.876 | 0.222 |

| Model 4 | 295.45 (216) | 1.368 | ∆ χ2 (m2, m4) = 6.98 * | 1 | 0.051 | 0.924 | 0.935 | 0.060 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarpong, S.A.; Akom, M.S.; Kusi-Owusu, E.; Ofosua-Adjei, I.; Lee, Y. The Role of Commitment in the Relationship between Components of Organizational Culture and Intention to Stay. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095151

Sarpong SA, Akom MS, Kusi-Owusu E, Ofosua-Adjei I, Lee Y. The Role of Commitment in the Relationship between Components of Organizational Culture and Intention to Stay. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):5151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095151

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarpong, Smart A., Mary Safowah Akom, Emelia Kusi-Owusu, Irene Ofosua-Adjei, and Youngjo Lee. 2021. "The Role of Commitment in the Relationship between Components of Organizational Culture and Intention to Stay" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 5151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095151

APA StyleSarpong, S. A., Akom, M. S., Kusi-Owusu, E., Ofosua-Adjei, I., & Lee, Y. (2021). The Role of Commitment in the Relationship between Components of Organizational Culture and Intention to Stay. Sustainability, 13(9), 5151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095151