1. Introduction

The requirements and expectations of customers in the modern sustainable services market are subject to dynamic changes [

1]. Innovation in recent years, mainly IT innovation, has revolutionized traditional models of service delivery and resulted in considerable changes in customer behavior [

2,

3]. New interactive technologies enable a more comprehensive presentation of the services offered, enhance the transparency of the process, and increase customer confidence, as well as maintaining constant contact using technology and mobile devices, widespread availability of mobile devices and the growth of social media has opened up new opportunities for service providers to communicate with their retail customers. CRM (customer relationship management) systems allow providers to monitor communications, analyze customers’ purchasing behavior and prepare customized offers. These systems also allow for the form and content of communication to be adjusted according to the customer’s expectations, and for the automatic sending of marketing communication designed to increase engagement, such as special offers, discount codes, and other incentives [

4].

However, in an era of ever-present and often intrusive marketing, such communications are often rejected or ignored, and the customers do not engage as much as the service provider would hope for. Service providers often do not have the knowledge necessary to create effective communication, especially online, and thus to increase engagement and develop the relationship between the customer and the brand [

5]. The issue of developing an enterprise–customer relationship is widely discussed in scientific literature from a general perspective, but the topic of managing customer involvement, including customers’ and providers’ commitment to developing a relationship as an essential element of building such a relationship is poorly studied. Most of the discussion of engagement in previous studies was related to marketing, and the biggest research gap concerned the inability to assess the degree of engagement on the part of the customer and the service provider, not to mention the possibility of comparing the obtained results. Moreover, with regard to modern services, largely based on interactive technologies, a significant proportion of the published studies concern organizational and commercial aspects of exclusively online services, e-business, and e-commerce solutions [

6], while issues faced by hybrid services are less well explored.

Hybrid services are defined as services delivered at the service provider’s premises, but are also supported by online communications [

7]. The study reported in this article involves hybrid services and aims to fill some of the knowledge gaps in regards to managing customer engagement and the importance of interactive technology for building relationships in sustainable modern services [

8]. For any type of service, mutual involvement between the customer and the provider is needed to grow the relationship. A smooth exchange of messages, with positive responses from both sides, using appropriate interactive technology, can facilitate such involvement. Most technology-mediated communication channels are managed by the service providers, who also control the decision-making process with regard to marketing activities. Therefore, this paper could be also of practical utility for the staff responsible for shaping customer relations in service companies. This practical/utilitarian aspect has, to some extent, affected the research approach in this study.

The specific goal of this study was to identify a new way of utilizing engagement as an important element of customer value management, from the perspective of developing a sustainable relationship between the service provider and their customers. This led to the following questions:

Research question 1: How can we identify the level of commitment in the customer/service-provider relationship?

Research question 2: How can we identify the deficit of commitment in the customer/service-provider relationship?

Answering these questions will allow for a better understanding of the mechanism for shaping engagement in the relationship between the service provider and their customers and identifying elements which, from the sustainable development perspective, will provide added value for the customers as well as the service providers.

The analysis presented in the article is based on desk research (literature review) followed by qualitative research including individual in-depth interviews (IDIs) with experts) and case studies in the service industries.

The purpose of this study was to create a model that would allow for the assessment of the level of customer and service provider commitment by identifying engagement deficits on the side of the customer or service provider.

The author’s intention is that the results of this research could—at least to some extent—fill the cognitive gap regarding the mechanism of shaping the mutual commitment of the service provider and the customer. In a practical context, the results could also turn out to be useful as a possible extension of the CRM concept, currently functioning in modern service companies, thus filling the application gap related to this problem.

2. Literature Review/Theoretical Basis

2.1. Traditional, Modern, and Hybrid Services

According to Dominiak, the classification of traditional and modern services is related to their susceptibility to technological progress [

9,

10]. Kotler et al. indicates that it is the cumulative effect of many technological changes which affects the perception of services as “modern” [

10,

11].

The changing technological environment has resulted in the emergence of new trends including the sharing economy, multi-channel integration, content marketing, and social engagement, constantly opening new opportunities in the development of modern services. Kotler indicates that the Internet is largely responsible for this state of affairs—we owe to it the increasing transparency of relations and the ability to connect with other people from around the world [

10].

The development of mobile technologies has led to the creation of mobile versions of online sales channels. Many companies selling services via traditional channels develop mobile applications as an additional sales channel for their services (e.g., booking cinema, theatre, or event tickets, or public transport tickets) [

12].

Thus, as can be inferred from the characteristics presented in

Table 1, modern services are knowledge-based, supported by technical/technological development and grow dynamically (generating GDP, increasing employment). For the purpose of this study, ‘modern services’ are traditional (non-digital) services provided with the use of interactive technologies.

A traditional service can turn into a modern one in several ways: through the modification and improvement of traditional services, modernization of ways of providing services, implementation of new technology in the service/support process, increasing the number of access channels, as well as the introduction of self-service and individualization [

15]. Gałązkiewicz points out that modern interactive technological solutions support the consumer experience, help to build image capital, and acquire knowledge about customers [

16,

17]. On the other hand, technology will not fulfil the task on its own, therefore a hybrid approach is needed, where technological solutions are ‘rooted’ in the real-world environment [

18,

19].

According to Kotler and Keller [

20], a traditional hybrid service combines services and a provision of material goods, e.g., a restaurant. In the case of modern services, a hybrid service may be provided partly in a traditional way and partly online, i.e., using the Internet or another electronic channel. Mixed (blended) services can also be distinguished, which involve the use of different access and management channels (telephone, internet or personal contact) e.g., a bank account [

21,

22].

Table 2 shows the distinguishing features of a modern service, broken down into those that are essential (and often also available in traditional services) and those that are optional. The essential (necessary) features must appear during or after the provision of the service; otherwise, we are dealing with a traditional service [

23]. The optional features of a modern service do not have to appear in order to conclude that the service is modern.

A traditional service can thus become a modern one if, for example, an electronic communication channel is created, it appears on social media, it has a mobile version of its website, it manages customer data (e.g., using a CRM system), it takes care of customer satisfaction by responding to not just formal complaints but also less-than-perfect feedback, or conducts regular customer satisfaction surveys electronically [

7,

23].

It is worth paying attention to inbound and outbound marketing, which also revolutionizes the modern sense of service provision [

24]. Inbound marketing can be defined as a strategy of attracting customer attention and interest by offering them content that responds to their needs. Such a strategy further develops the relationship between the customer and the service provider. The main purpose of inbound marketing is to answer specific questions and help in solving the problem faced by the customer/user, e.g., through advisory, specialized or expert content that is published on social media and is also optimized for search engine purposes (so can be found easily using search engine queries) [

25]. Such content includes blog entries and articles, posts, graphics, and videos on social media and on the various websites, e-books, podcasts, and other formats that allow the delivery of valuable content to recipients. This strategy allows the service provider to build their own brand image as well as facilitates the growth of customer loyalty.

The use of interactive technology is a significant component of a modern service, and is necessary for its operations and for reaching customers.

2.2. Customer Satisfaction, Loyalty, and Commitment

Customer satisfaction with the service is related to the quality of the service, as well as the needs, values and expectations of the customer [

26]. It is emphasized in the literature that customer loyalty is the main result of achieving a high level of customer satisfaction [

27]. This means that we can treat customer loyalty as a function of satisfaction. As Mitraga indicates, we can consider satisfaction from three perspectives [

28]:

Satisfaction with interaction with the provider’s staff (‘customer service’)

Satisfaction with the actual product/service

General satisfaction with the relationship with the company

Customer satisfaction turns into loyalty by building trust. Trust is also an essential element in creating commitment, since ‘threshold trust’ is necessary for the development of a relationship while using interactive technology, the relationship between the customer and the service provider can be gradually developed, resulting in (increasing) customer loyalty.

Customer satisfaction results in customers returning repeatedly to the same service provider, i.e., customer loyalty. According to Gilmore, the most widely accepted definition of customer loyalty defines it as the behavioral effect of a customer’s preferences for a particular brand or similar brands, which becomes apparent over time and is the result of a value-based decision-making process [

29] (p. 30). In contrast, Jones and Sasser state that loyalty is a feeling of connection and attachment to a company or affection for the products it offers or the people working for it [

30].

Customer commitment is key to building brand loyalty and lies at the conceptual core of the solution proposed in this paper. In English language literature, one finds much discussion of ‘customer involvement’, with this term indicating one of two phenomena: (1) ‘commitment’, meaning an attitude related to the willingness to take specific actions (a pragmatic aspect of involvement) [

31] and (2) ‘engagement’, meaning an attitude of interest in e.g., matters of a favorite brand (positive emotional involvement, but not necessarily implying the willingness to take action). In the context of this article, customer involvement is understood in terms of commitment [

32]. To build customer loyalty and commitment, elements derived from psychological science are frequently used, but beyond them, there are also relationship aspects that are described by relationship marketing (also called partner marketing) [

6,

33]. Maintaining and acquiring customer loyalty is a long-term process which requires systematic efforts from the service company and its employees. The type and scale of actions taken depends on the current level of customer relations [

34].

2.3. Open Innovation in Customer Value Management

Although the idea of innovation processes is not new, a new approach has been developed which emphasizes new opportunities arising from innovation management. This new approach is open innovation—which, unlike traditional (closed) innovation processes which utilize ideas arising within the company’s structures—is open to innovative ideas arising ‘externally’ and combining them with in-company ideas to develop and launch new technologies, products, and services. As Sopinska points out, open innovation provides an opportunity for companies to grow, because skillful integration of internal and external solutions is the key to creating advanced combinations of knowledge that result in gaining a competitive advantage [

35,

36].

In order to take advantage of the opportunities offered by open innovation, it is necessary to build good relationships with customers, who are an excellent source of information. This building of customer relations can be supported by relationship marketing.

2.4. Relationship Marketing

Experience marketing, where the people responsible for marketing look at the world through the eyes of the customer, is more commonly used in marketing modern services. A new marketing paradigm, focusing on ‘experience’ that is understood as every interaction, at every point of contact between the customer and the brand or product/service, thus emerges [

37]. ‘Experiences’ are thus a result of the company’s activities stimulating the customer’s senses and/or evoking feelings towards the product/service or the customer themselves. Boguszewska-Kreft defines the marketing of experience as “the process of creating, maintaining, enriching and deepening the company’s interaction with the customer by providing memorable experiences that will engage and emotionally connect customers with the brand” [

36] (p. 53).

Emotions are key to experience marketing. The role of customers is changing in modern services. The customer is no longer seen only as a service buyer, but as a creator of value created by combining the resources provided by the company with those of the customer. Nowadays, companies no longer have to create value for the customer—it is sufficient to properly cooperate with the customer and co-create the value the customer expects [

3].

2.5. Co-Creation as a New Element at Customer Value Management

The role of the customer in designing processes, services or finished products is important as the subject of design is more and more often adapted to the expectations of the customers (users of the service). Each customer has his/her own preferences and expectations. Systematic research of customer expectations has shown that customers expectations are growing, and that customers themselves are aware that they decide on the sales success of a given product or service [

4].

When the provider/customer relationship is of sufficient quality, the customers participate more and more in the process of service provision: from defining the requirements related to the service itself to providing after-sales feedback. The customer is best aware of what he/she expects from the service provider [

37]. As Beemer and Shook emphasize, a customer’s interest in contributing to the creation of value can also be influenced by their lack of satisfaction with the products or services currently available in the market [

38].

Prahalad and Krischnan point out that co-creating value with customers is one of the key elements in the process of generating innovation, providing a particular opportunity to create new services or improve existing ones [

39]. Nowadays, customers are increasingly aware of their purchasing power and, furthermore, when making a transaction, they (attempt to) get maximum benefit from the seller. Two new customer roles have emerged in the world of innovation and value: the customer as a value co-creator and the customer as an innovator [

40]. A value co-creator is a person who creates value in the form of information, guidance or idea that the service provider, after analysis, introduces into the organization and thus creates new, better value, which he will in turn provide to his customers [

38]. It may be an idea to extend a given service with an additional element, which the service provider has not paid attention to, and the customers have missed a lot. On the other hand, an innovator is a person who proposes new solutions, not necessarily constituting some value for the service provider, but innovative enough to be worth working on and implementing in working groups in the company [

4]. Entrepreneurs turn to customers not only to have them make a purchase, but also to encourage them to act as consultants or as regular customers to get involved in the process of designing products/services [

38].

Thallmaier also points to the possibility of interaction with other people about ideas, product appearance, design, etc. Moreover, it is possible to evaluate the new ideas in social-networked communities and propose them for mass production or permanent inclusion in the catalogue of services [

41,

42]. Thus a new type of customer has also emerged—the prosumer, i.e., the customer who is involved in co-creating or promoting a product or service [

42]. Interactive technologies engage the customer, trying to transform the consumer into a prosumer. Such participation of customers can improve the services provided by entrepreneurs as they are a key factor in the development and improvement of services [

18,

43].

2.6. Service Provider/Customer Relationship

Relationships are built through the cyclical accumulation of positive customer experiences. For service companies, taking care of very good relations with customers is supposed to lead to a situation in which customers will want to use only the services of a given company when they want to satisfy a given need. Relationship marketing comes down to taking care of existing customers and the long-term nature of interactions, resulting in closer cooperation and more transactions.

According to Fazlagic et al., a well-developed customer-provider relationship also generates additional roles for the customer [

4,

42]:

customers transfer their knowledge about the company to other customers (word of mouth marketing),

customers provide testimonials, which later help to win more customers,

actively participating in the co-design process and presenting their own expectations, customers motivate the company to introduce innovations,

customers can contribute to improving the company’s image,

customers can contribute to the improvement of the level of service and developing competences of customer service staff,

customers stimulate the company by submitting complaints, providing motivation to analyze errors and continuously improve processes and services.

Loyalty relationships are among the most sustainable benefits because they are difficult for competitors to understand, copy, or acquire. Communication and information sharing are essential sources of trust and relationship development [

43,

44].

By using experience marketing, the company creates the appropriate conditions for adjusting the service to the customer’s requirements, and thus improves customer satisfaction, which builds the relationship between the customer and the service provider, while consolidating it at the same time. It is the positive, accumulated experience of the customer that strengthens his/her loyalty, increases the number of purchases made by him/her and contributes to the increase in (the number of) times the customer recommends the service provider to others [

45].

In modern services the customer’s growing involvement together with his or her growing participation play a key role in improving the quality of the provider/customer relationship.

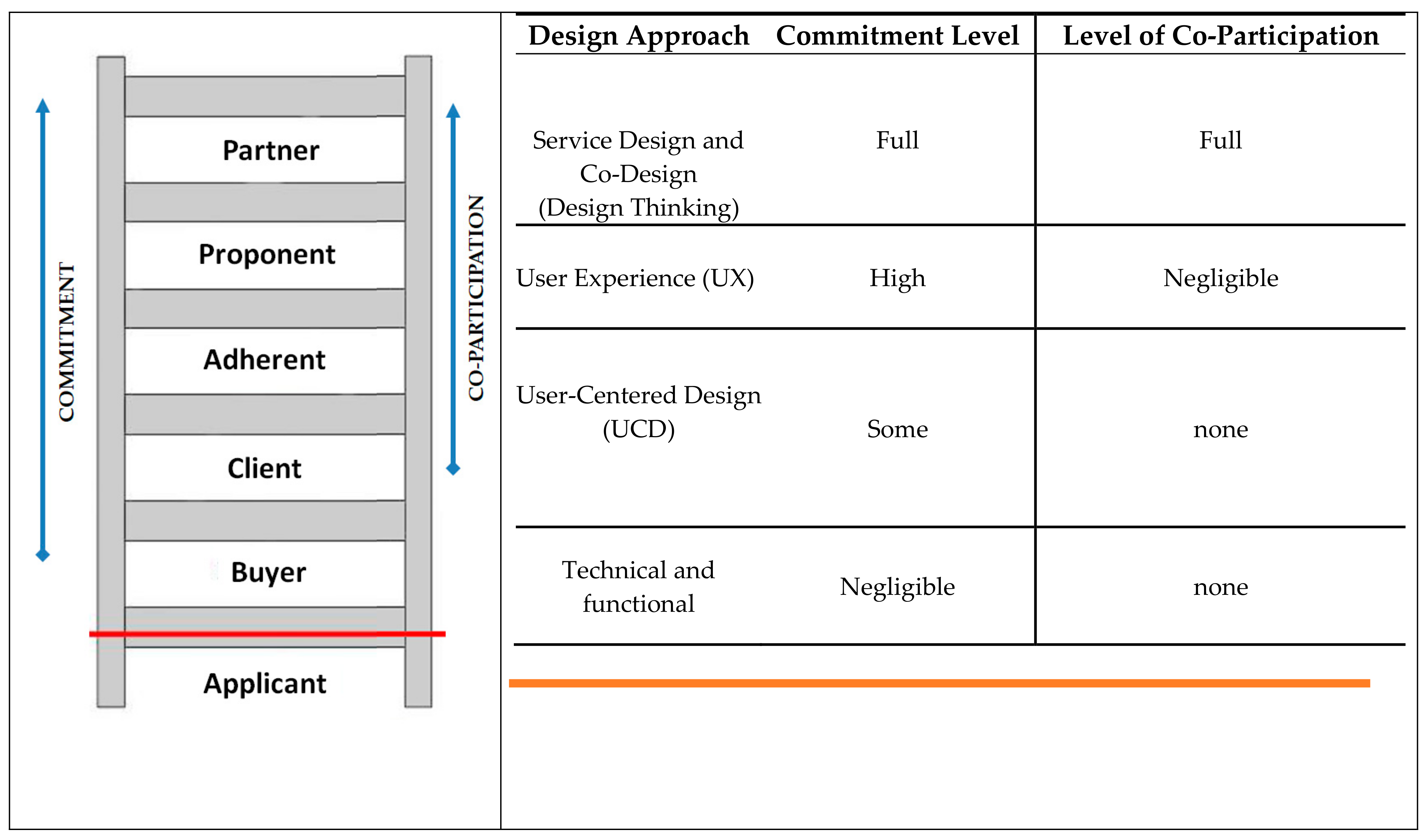

Figure 1 (left part) illustrates the relationship between co-participation and customer involvement in developing the service provider–client relationship. Regularities can be observed in the above figure:

The relational mechanism develops by increasing involvement.

Commitment precedes participation.

Participation is the result of strengthening the relationship.

As can be seen in the right-hand part of

Figure 1, the technical-functional approach uses the customer’s commitment only to a negligible extent. On the other hand, the UCD approach makes greater use of customer involvement, but does not use customer co-participation, unlike the subsequent UX approach, which already makes almost full use of customer involvement and makes partial use of customer co-participation. The design approach, service design, makes full use of customer engagement and, to a large extent, customer co-participation. The co-design approach, on the other hand, makes full use of the customer’s commitment and co-participation for the design and improvement of services—mainly modern services.

2.7. Sustainability Development Perspective

The development of processes related to increasing customer involvement has been accompanied by the emergence of the concept of socioeconomic sustainability, which regulates aspects related to the delivery of customer value [

46,

47]. Sustainability is very important for all “aware customers”, i.e., the customers who make their purchasing choices consciously, and in consideration of sustainable development goals (5 × P): people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership, as specified by the UN [

47,

48]. Such customers follow trends influenced by the current sustainable development concerns, which in turn increases their awareness and creates a trend towards (increased) involvement in customer-provider relationships [

1,

2].

2.8. Interactive Technologies in Modern Services

Modern services are based on the interaction between the user and the system, i.e., between the customer and the service provider. Interaction may involve people, objects or phenomena. Interaction can also be a way of exerting influence and synchronized action using feedback [

49,

50]. Interactivity is characterized by bi-directionality, timeliness, mutual controllability, and response [

51].

Interactive technologies have the potential to enable organizations to better respond to market needs compared to traditional solutions. Interactive systems adapt their behavior under the influence of signals from the environment either via their sensors or in response to human behavior (e.g., the customer). Social media, an interactive technology by design, whose influence has been growing for several years now, can complement and increase the value of any customer-brand interaction—now or in the future [

52,

53,

54]. Using interactive technologies to maintain customer relationships brings about significant changes and allows for the sharing of content and reactions between people and communities that are dispersed, enabling communication despite barriers [

55,

56,

57,

58].

According to the 2020 report for Simon Kemp, the share of Internet users on computer/laptop devices is decreasing from year to year by 6%. In a report from January 2021, 41% Internet users use a desktop or laptop computer to access Internet [

59,

60]. Interestingly, a significant increase in Internet users’ activity on mobile phones can be noticed. According to data from 2020, every second Internet user browses on a mobile phone (56%), which is a 4.6% increase from 2019 [

59,

60].

With the rapid growth of smartphone use facilitating widespread Internet access on the go, interactive technologies will be used more and more frequently by individual customers. This makes it possible to maintain a customer/service-provider relationships practically uninterrupted, limited only by data coverage [

59,

60,

61,

62].

As Adobe stresses in its 2017 report, the era of mobility had already arrived in 2017 [

61,

62]. Today, a Cisco report shows dynamic changes in Internet usage over the last two years, predicting 50% more Internet connections by 2023 in comparison to 2018, as an effect of the implementation of 5G, IoT (Internet of Things) and Internet-enabled home appliances and devices [

61]. Today, mobile devices are still the main devices people use to access the internet at home [

60,

61,

62], and the COVID-19 pandemic has not halted the trend towards mobile, though no detailed data is yet available.

The same study reports that for every 3 min spent using a mobile device, 2 min are spent consuming digital media and more than 50% of all searches are done via mobile devices [

60,

61]. Adobe’s research also points out that the customers expect to be able to find a solution to their needs in no more than two minutes online. Brands/companies that do not work to be easily accessible through interactive technology will lose their market position [

38].

Examples of interactive technologies on the side of the service provider include CRM systems, social networks, augmented reality, systems using artificial intelligence (bots, chatbots and others), blogs, affiliate marketing, geolocation, search optimization, videos and webcasts, machine learning, gameplay, interactive ads, and crowdsourcing. Examples of interactive technologies on the customer side include: web browsers, mobile devices and applications, augmented reality, social TV, image recognition, mobile tagging (use of QR codes), and geolocation.

The advent of interactive technology marks the beginning of the fourth phase of marketing, Kotler’s marketing 4.0, also known as digital or interactive marketing [

11].

2.9. Social Interaction in Customer Value Management

Social media based virtual communities have developed, focused on blogs, microblogs (e.g., Twitter, Tumblr), discussion forums, wikis (e.g., Wikipedia), video and photo content sharing platforms (e.g., YouTube, Instagram), social content aggregators (e.g., Digg, Reddit), and social networking sites (e.g., Facebook) [

55,

63].

Social media based activity allows service providers to develop and improve relationships with their customers, which may translate into a higher frequency (or value) of purchases [

51]. Currently, the growth of online communities is still an ongoing phenomenon. Kotler calls such relationships “horizontal” [

11]. They revolutionize modern services by introducing integration, social influence and the sharing of opinions, both good and bad, which affects the transparency of services provided. At present, we notice a dynamic development of Internet communities [

60]. Looking at social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram), it can be observed that this trend towards creating online communities seems to be able to generate new kinds of e-services. Communities attracting more and more Internet users create new sales, promotion and communication channels. As a result, the customer–supplier relationship takes on a new shape. Companies start to appear in communities with company websites, advertisements, competitions, promotions and other incentives for customers to contact the service provider [

64]. Few companies sell directly via their social media profiles, but rather use social channels to maintain relationships. Additionally, companies run promotional campaigns on social media to attract new customers with special offers or competitions. Moreover, specific communities emerge in relation to their use of social media, becoming ready-defined market segments for specific (niche) modern services [

64].

Brands using traditional promotion channels—such as television, radio, press, and outdoor advertising—realize that these forms of promotion are not fully satisfactory.

3. Materials and Method: Research Methodology

3.1. Choice of Methodology

As the topic of customer involvement in the service industry is more relevant to businesses serving retail customers, the author decided to narrow the research to the hotel, automotive, and catering service sectors.

For the same reason, the model proposed in this article applies to individual consumers only, as wholesale and business customers have different characteristics and the involvement of the individual customer has a significant impact on the involvement of the service provider. For the purposes of this study, it had been assumed that in order to successfully build and develop a relationship, the involvement of both parties (the service provider and the customer) must be characterized by symmetrical reciprocity, otherwise the relationship stops developing. The qualitative approach was chosen as, on the one hand, the scope of the project did not allow for a sufficiently large sample of companies, or access to numerical data from their CRM systems, while on the other hand, a lot of corporate knowledge on building customer relationships is of an informal nature, specific to a particular service, and even the specific company and individuals within the company. Thus, individual qualitative interviews and case studies have been chosen as the optimal approach to explore this subject area.

Qualitative approaches have been widely and successfully used in marketing science, and are in general particularly suited to explore relatively new areas of interest and conceptual models. Numerous authors [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69] consider that a qualitative approach including case studies is the optimal way to acquire new knowledge, as it allows for the creation of theoretical models derived from business practice (bottom-up approach). Inter alia, qualitative approaches enable a more detailed investigation and exploration of the studied phenomena, including specific data relevant to a particular industry or even individual company. The ultimate goal of the project was to create a model using the team design method involving a group of expert-managers. This process is qualitative and iterative in nature, with conceptual solutions and step-by-step results verified and validated with reference to the professional experience and competence of the participating experts. Additionally, the chosen qualitative approach allowed for the inclusion of company-specific data and documents, which led to the completion of case studies. The data was gathered through individual interviews, group interviews and workshop sessions using visual communication techniques.

3.2. Method

The project consisted of several stages. All the presented data related to the case studies conducted in the above-mentioned industries are based on the data collected by the author as part of this article and his own research. At the stage of preliminary research, the aim was to obtain an overview of the service market, select the services to be researched and describe case studies. The service market was analyzed in order to select services which were ‘the closest’ to the customers, i.e., where brand relationships or bonds with the service provider are strong and repeatable. The choice of industries was also determined by access to data, experts, and the following criteria:

network services,

standardized services,

services with a specific customer relationship mechanism,

services using the Internet to communicate with customers.

Therefore, three service sectors meeting the above criteria were selected. Such a choice was also supported by the availability of experts holding high managerial positions in companies, ready to take part in interviews. The selection of the industries was the first step to select (within the selected industries) service companies where the case studies would be completed. Based on the examples from the selected industries, a commitment model would be built and tested. The following service industries were selected, and data for three case studies within each industry (nine cases studies in total) was collected:

In the second step of the preliminary phase, service companies suitable for case studies were selected and the basic data about them was collected in the form of ‘description sheets’. Analysis of the service markets that were selected for the study, as well as company documents were used for the purpose of cases studies. The description sheet provided basic information about the service provider, the company’s business profile and the existing forms of customer participation. In addition, examples of projects or activities that included customer participation were also included in the description sheets, with notes on the results of such co-participation, if there was any.

The main techniques used for data collection were interviews. Two types of expert interviews were conducted: individual in-depth interviews and group interviews. Nine individual in-depth interviews (Interview 1—part A) and one focus group interview (Interview 1—part B) were completed with experts from the selected industries. Individual in-depth interviews were carried out to obtain information on factors that affect the degree of customer and service provider commitment in the process of providing the service. A focus group interview of a creative type was conducted to provide creative solutions to the issue of engagement in the service provider-client relationship. To qualify for inclusion in the project, the expert-managers had to be working in the selected company for more than three years, hold a high managerial position, manage a team of people and have influence on making strategic decisions. These people had access to all company data. All experts had high decision-making capabilities and extensive knowledge of processes taking place within the company.

The market for services was analyzed and on this basis the industries for research were identified. From these industries, service companies and services were selected for research.

4. Results

According to RQ1: How can we identify the level of commitment in the customer-service provider relationship?

In most cases, the mechanism of building customer relations works according to the “customer loyalty ladder” model proposed by Payne [

44]. Since it is not possible to build a relationship without first triggering positive involvement with the customer, a similar conceptual framework has been adopted by analogy in this study, where the development of commitment takes place successively through specific stages (levels), growing in intensity and having a positive impact on the development of the provider/customer relationship.

Payne indicates that the most effective way to market services is via the company’s customers [

14,

44]. This is shown by the example of the ladder of customer loyalty in the context of partner marketing, where based on the types of customers (buyer, client, adherent, proponent, and partner), six levels of customer loyalty are distinguished [

70] (pp. 44–79). Moving up the loyalty ladder means increasing customer loyalty to the service provider. Promotion to the next level takes place individually, step by step.

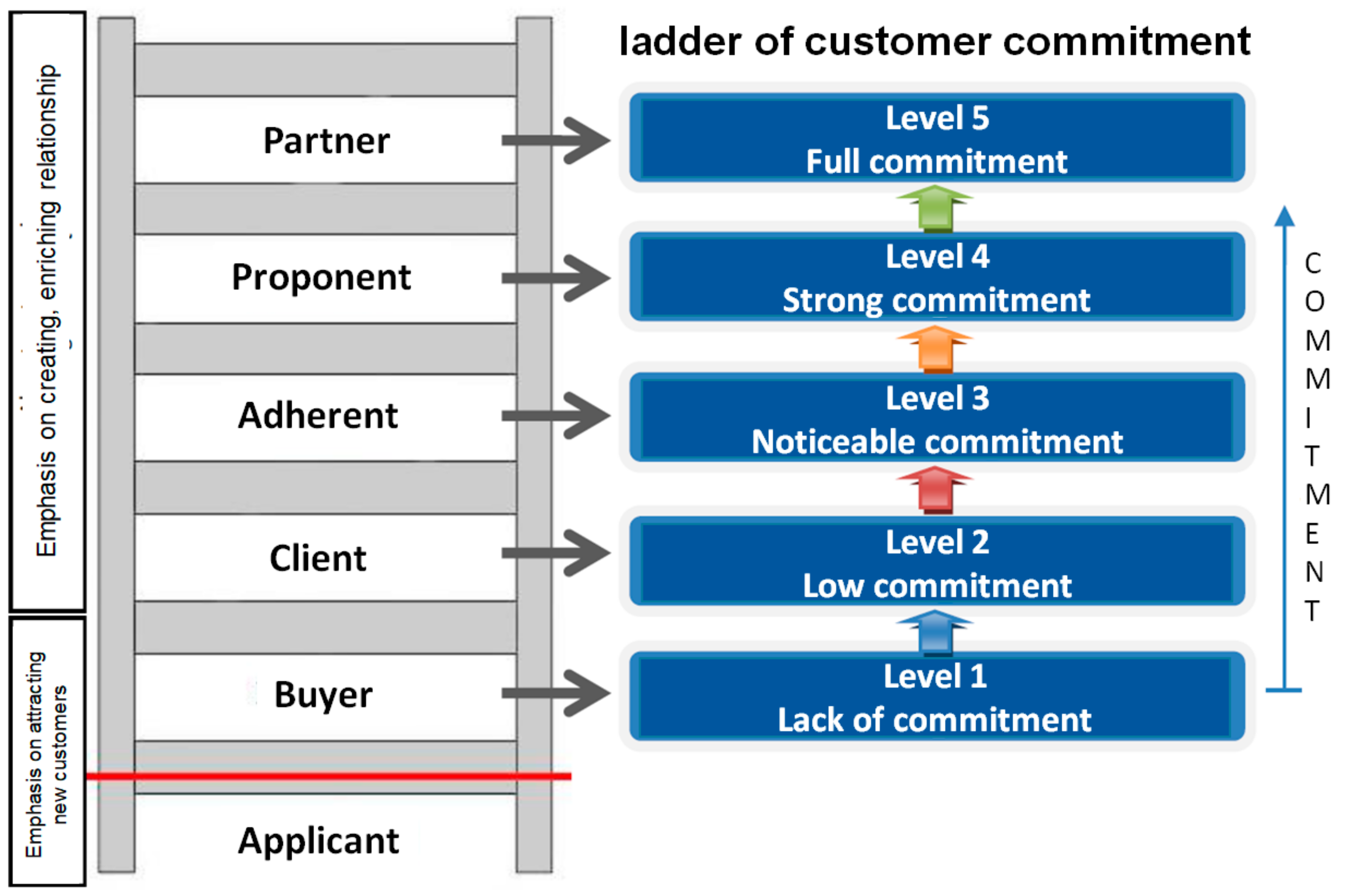

As efforts to gain customer loyalty come down to involving the customer, a ladder of service provider/customer commitment (

Figure 2) can be proposed by analogy to the ladder of loyalty (

Figure 1).

The proposed service provider/customer commitment ladder (

Figure 2 on the right) consists of five levels of commitment, i.e., one less than Payne’s original customer loyalty ladder. The lack of one level is due to the assumption that the applicant is not yet a customer (a service buyer), but only a person aspiring to be a customer and therefore cannot be included in the ladder of customer-service provider commitment. The horizontal red line visible in

Figure 2 indicates the starting level for the customer-service provider commitment ladder.

The loyalty of the customer, which has its roots in relationship marketing, is closely linked to the proposed levels of commitment. Loyalty is built on the basis of good customer-service provider relationships, which is closely linked to commitment, which is also built on the basis of customer-service provider relationships.

Following the literature review and interviews with experts, the five levels describing the degree of commitment on the part of the customer and the respective, symmetrical five levels of commitment on the part of the service provider were defined. The symmetry means that each level on the customer side has its counterpart on the service provider side. The higher the level of commitment of the service provider, the better for them, as this means that the service provider is ready to work together with the customers. How to increase the level of commitment is presented in

Table 3.

Table 3 shows five levels of customer and service provider commitment. Commitment develops in stages from Level 1 through Levels 2–4 to full involvement at Level 5. As shown in

Figure 2, commitment development is a phased process. The transition from Level 1 immediately to Level 4 is impossible. It is necessary to go through the different levels in order to reach full commitment. This applies to both the customer and the service provider, because their behavior—as well as the levels—is symmetrical to each other. The vertical arrows indicate an increase in involvement on both the customer and the service provider side. The proposed model assumes that the increase in involvement does not have to be identical for the customer and the service provider.

A ladder of customer-service provider commitment (

Figure 2), combining the two sides of the relationship (the customer and the service provider) and a sequential increase in the level of commitment, offers a model of customer-service provider commitment. This model will allow for the creation of a tool for more precise analysis of the commitment in the relationship. The tool, in conjunction with practical data, will allow companies to identify and describe elements of their existing customer-service provider relationships, and further develop these relationships, thus generating higher levels of involvement in both parties.

Table 3 summarizes the five levels of commitment which can be further described as follows:

LEVEL 1 is characterized by a lack of involvement. This is due to the fact that although the service provider has created forms of involvement and built relationships with the customer, they do not provide information about them or promote them. An example would be the service provider launching a loyalty program in the absence of any information on the service provider’s website or a failure to include the information about the loyalty program in the customer service procedure. On the other hand, a lack of involvement in the case of a customer at Level 1 identifies the customer as a person who knows about the existence of the loyalty program, but due to the lack of involvement does not sign up for and benefit from the membership of the loyalty program. Once the relevant commitment factors are properly met, it is possible to move from Level 1 to Level 2.

LEVEL 2 means occasional interactions between the customer and the service provider. This level identifies a customer who has shown low commitment in the form of a desire to subscribe to a loyalty program, for example, which results in an establishment of a customer–provider relationship. On the other hand, a service provider with low involvement informs and invites its customers to participate in active forms of involvement, e.g., invites them to subscribe to receive commercial information (a newsletter). Once the relevant commitment factors are properly met, it is possible to move from Level 2 to Level 3.

LEVEL 3 means noticeable involvement of the service provider, during which the service provider makes available and communicates to the customer the opportunity to participate. The provision of access to a customer account, where the customer may indicate which commercial information he or she wants to receive from the service provider may serve as an example of such participation (e.g., in the hospitality industry the customer may choose to be informed about news or promotions in hospitality services but is not interested in fitness/SPA promotions), and in addition he or she has the option to check how often he or she wishes to receive this information (e.g., once a week). On the other hand, as far as customer commitment is concerned, the customer expects such access and signals that he or she would be interested in this form of co-participation with the service provider. Once the commitment factors from Level 3 are properly met, it is possible to move to Level 4.

LEVEL 4 means a strong commitment where the customer reacts and engages in the forms of involvement proposed to him by the service provider. An invitation for the customer to complete a survey on a website, in which the customer is asked to indicate what should be improved to make him or her use of the website more frequently, may serve as an example of such an involvement. On the other hand, a service provider at this level tries to involve its customers in activities aimed at co-designing services or processes taking place in the company. Once the commitment factors from Level 4 are properly met, it is possible to move to Level 5.

LEVEL 5 indicates the highest degree of commitment, that is, ‘full commitment’. The service provider at this level invites and eagerly cooperates with the customer on joint design and improvement of processes taking place in the company. On the other hand, the customer at this level cooperates with the service provider and is fully engaged in the design processes taking place in the service provider’s company.

The proposed commitment ladder provides the answer to the RQ1 posed earlier in this article, allowing for the identification of the level of involvement in the provider/customer relationship using five levels symmetrical for both sides of such relationships.

Identification and Classification of Commitment Factors

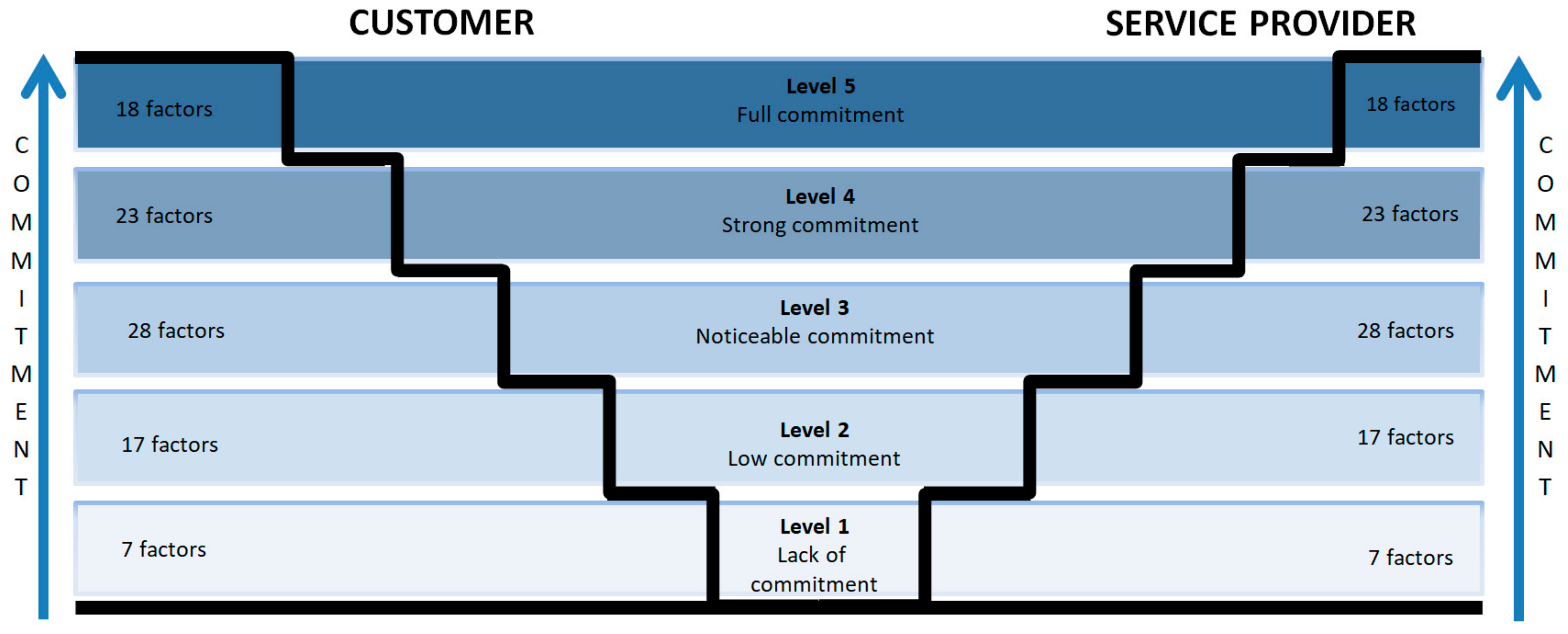

Figure 3 shows the customer-service provider commitment model based on the commitment ladder. Within each commitment level, component factors function as elements of the model under development. These factors (‘commitment factors’) are used to determine the degree of commitment by assessing the extent to which they are fulfilled.

The total number of commitment factors on the customer and service provider side is 93. Each customer commitment factor has its counterpart on the service provider side. The number of commitment factors at each level is identical on the customer side and on the service provider side.

The idea of constructing commitment factors is based not only on hybrid services but also takes traditional services into account. The emphasis on hybrid services was placed by experts who noticed that the use of IT technology was revolutionizing those services and gave them more opportunities to engage customers. That is why elements of hybrid as well as traditional services were used in constructing the engagement factors.

All commitment factors have been identified through individual in-depth interviews (Interview 1A) and a focus group interview (Interview 1B) with experts from the companies/brands participating in the study. Three experts from each industry participated in the study. The people invited to the study had all been working in the industry for over three years, were managing a team of people, and had practical knowledge about issues related to building relations with the customer. At least one person from each company/brand was invited to the study. Together, they formed a group of experts consisting of nine people. As a result of the interviews with the above experts, 14 groups of factors were identified, which are described in classification.

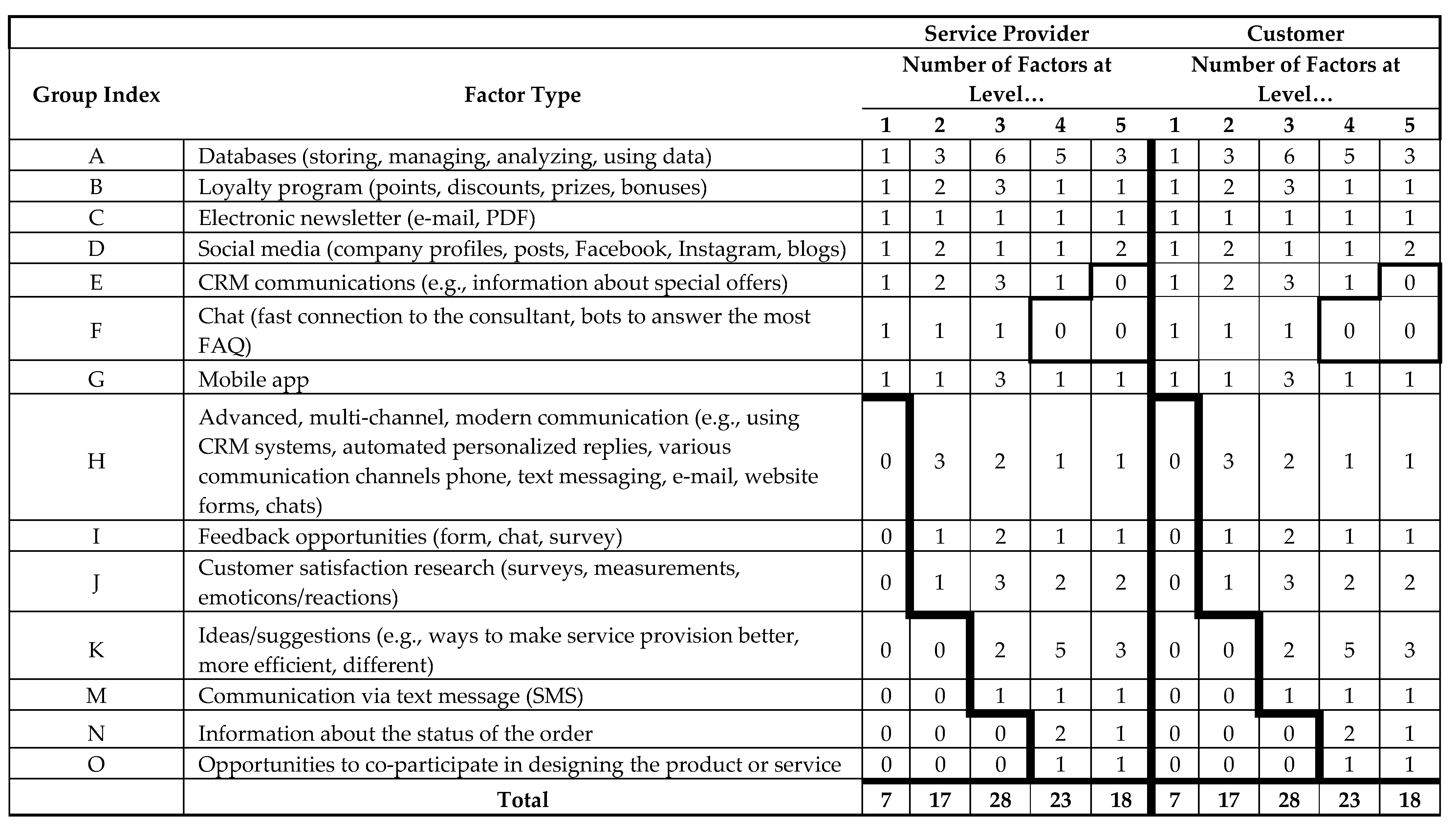

Table 4 shows the distribution of factor types at successive commitment levels. The factors presented in

Table 4 were derived as the result of Interview 1 and Interview 2 with the experts. Factors belonging to groups A–D and G occur at all levels of the commitment model, but their specifics change with increasing levels of commitment. It can be noted that the last two groups—i.e., service process status and service co-design—appear only at Level 4 and Level 5. It follows that Level 4 and Level 5 are characterized by the highest level of commitment. Detailed analysis of factors will be a subject for subsequent publications.

The commitment factors were identified and then classified and grouped according to the developed commitment levels indicated in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 and in

Table 4. The developed classification of commitment factors was used to create elements of the model to be used in the interaction model, the bootstrapping concept.

According to RQ2: How can we identify the deficit of commitment in the customer/service-provider relationship?

In order to identify the key factors determining the level of involvement in the service-provider/customer relationship, a pilot study was completed on the basis of simulated customer data generated on the basis of the interviewed experts’ identifying characteristics of typical customer groups.

The results suggest that the level of customer commitment varies for different types of customers at different levels of the ladder.

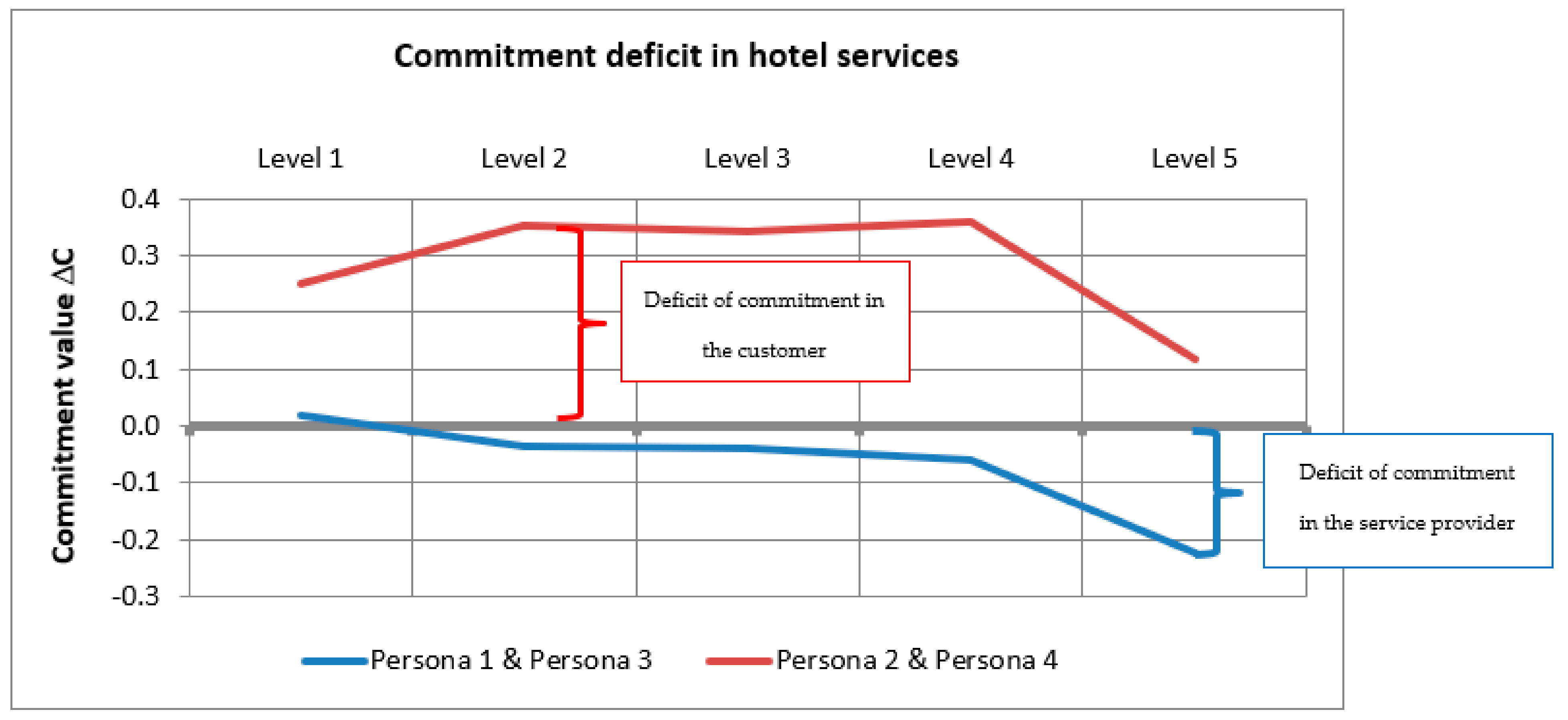

Figure 5 shows an example of the commitment deficit on the part of the consumers and the service provider at particular levels of commitment, answering the RQ2, and demonstrating an example of a form of data visualization that, when using actual customer and company data, will allow for the identification of deficits in provider commitment (blue) or customer commitment (red), made possible through utilization of the ‘commitment ladder’ proposed in this article, which allows for identifying distinct levels of commitment.

Figure 5 shows the phenomenon of a customer and service provider’s deficit of commitment at particular commitment levels, where it can be seen that a customer’s lack of commitment occurs between Level 2 and Level 4. There is a lack of commitment on the part of the service provider at Level 5, where the service provider should take corrective action to improve their commitment level compared to that of the customer’s. This may be due to the fact that the hotel industry too rarely invites customers to the co-design process, which is at the highest level of commitment.

5. Discussion and Future Research Direction

The proposed ladder of commitment features five levels of commitment to build relationships, which are analogous to Payne’s ladder of customer loyalty [

44].

The ladder is symmetrical—the levels on the provider side and on the customer side are identical, which makes it possible to compare the degree of commitment of the provider and the customer, thus obtaining meaningful results that allow the data obtained to be used in practice in the next step, i.e., to improve the degree of commitment. The question is whether the symmetry of the levels of commitment is the desired outcome for any enterprise in any case [

71,

72]. The research reported in this article suggest that it is, but the question remains whether it is similar for other types of services? For some companies, striving for the highest levels of commitment will provide a profitable return on the investment they will have to make to try to achieve them.

The proposed ladder structure is characterized by the fact that at each level the constituent factors affecting the achievement of a certain level of commitment by the service provider and the customer (different for each party in the relationship) have been identified.

The mechanism for increasing commitment utilizes bootstrapping, which means a change (increase) in the level of commitment as the interaction progresses, which occurs when the factors of a given level have already been fulfilled to an appropriate degree-then factors from the next, higher level are triggered, resulting in an increase in the level of service provider/customer commitment through interaction [

73,

74]. It is not clear whether this mechanism, which is typical for the IT sector, is universal enough to be used to increase commitment in other industries.

In addition, the ladder describes a sequential increase in the levels of commitment, which makes it possible to analyze and identify the level of commitment achieved, as well as to define the actions necessary to improve the outcome and move to a higher level of commitment. It should be remembered that the increase in commitment does not have to be the same for the service provider as for the customer.

Using the proposed ladder of commitment and the whole mechanism of commitment in the service provider/customer relationship, it is possible, with sample test data, to obtain simulated results and answer the RQ2. Using the different levels, the identified factors that influence each of them and substituting the data obtained from the service provider and the customer, it is possible to determine the deficit of commitment that exists in the service provider/customer relationship. Such analysis and the results obtained can allow for the identification of zones/elements in customer value management that need to be worked on in order to achieve a balance or higher levels of commitment from each party in the service provider/customer relationship.

Future research should involve developing practical recommendations for managers. Furthermore, developing a practical diagnostic tool that goes beyond the current model would make it possible to apply the results presented in this article in business practice. Practical implementation would culminate in the development of a series of procedures which should translate into improving the functioning of service companies by strengthening relations with their customers, through the use of interactive technologies.