Abstract

There is a broad consensus on the impact of teacher quality on students’ outcomes. However, the debate on how to evaluate the impact of teacher training on student improvement remains open. The evaluation of the impact of in-service teacher training, organized in a network for different schools, has been analyzed very little to date. Our research displays an innovative approach in this regard, through an In-Service Professional Development Program based upon scientific evidence and dialogic principles: The Pedagogical Gatherings “On Giant’s Shoulders”. We conducted a multilevel communicative study to analyze its impact upon students’ achievement and schools’ outcomes whose teachers taking part of the Gatherings. Our contribution provides an advancement in the analysis of educational impact in teacher training. We provide indicators to identify those training programs that improve educational outcomes, according to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal number 4: quality education for all.

1. Introduction

Teacher professional development is on top of the education policy agenda, as many governments have become convinced that teacher preparation and development is a key building block in supporting teacher’s good practices [1]. Moreover, having properly qualified teachers is one of the targets of the Sustainable Development Goal on Quality Education [United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://sdgs.un.org/es/node/24494 (accessed on 7 April 2021). There is broad consensus on the impact of teacher quality on student’s outcomes backed by numerous studies [2,3,4,5,6,7] as well as international policy recommendations, both European [8,9] and non-European [10,11]. Moreover, scholars agree that teacher professional development is an essential condition for school improvement [12,13]. However, teacher professional development is connected with other levels of the educational system and the whole society [12]. Teacher professional development may interact and impact on school outcomes, but it may not have a linear effect [14].

International literature on school effectiveness shows that successful teacher professional development should be addressed from a systemic approach [1] to ensure that quality teaching is supported across all schools and classrooms. Accordingly, teacher learning and development must be conceptualized as a complex system rather than as single events [13]. Viewed from a complex approach, teacher development is defined as an action that occurs at the individual, collective and organizational level. In a comprehensive literature review, Opfer and Pedder found that teacher learning at the individual level is supported when teachers have opportunities for (a) reflection, (b) understanding their environment and their challenges and c) applying knowledge about teaching and learning [13]. Moreover, collective and organizational learning within schools is supported when (a) learning is nurtured across all levels of the school, (b) self-evaluation is promoted as a way of learning, (c) there is an examination of implicit values, assumptions and beliefs underpinning institutional practices and (d) there is a knowledge management system that leverages capabilities and expertise of staff and pupils [13]. Current studies seek to find evidence on the association between teacher training, quality and effectiveness of teacher professional practice and its impact on students’ educational success [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

In the Spanish context, research has shown the scarce and limited impact of teacher development upon teacher’s practice. Findings show that teachers change their practice as a consequence of participating in teacher development initiatives, but they believe these changes do not improve students learning or at least this improvement is not straightforward [12]. Some scholars have provided explanations for this outcome. For example, González-Vallinas et al. [13] showed that most teacher development initiatives are not focused on specific-knowledge content and claim that these should take into account groups of teachers, instead of individual teachers, and should include reflection and awareness of the students’ contexts. Further research has shown that teacher training courses are biased towards a technical-oriented approach of teaching, emphasizing instructional methods while omitting socio-familiar and community issues [23]. Therefore, teacher development lacks sensibility and responsiveness towards social and cultural factors of the teaching practice.

Based on this background, we aimed to apply a multilevel model of educational impact evaluation of a continuing teacher training program based on scientific evidence and dialogic principles. Through a case study focused upon a Dialogic Pedagogical Gathering in Valencia (DPGv), we performed a first analysis of the impact of the program in the educational improvement of all 17 schools that took part in the study. We conducted our research in two phases, which allowed us to identify educational improvements at different levels that make it possible to know more precisely the link between educational impact and DPG. With this study, we intend to bring new knowledge to the international debate on teacher training actions that affect educational improvements in communities.

1.1. Scientific Evidence-Based Teacher Professional Development

The international movement ‘scientific evidence-based teacher education’ means putting international scientific evidence at the service of educational improvement. Several studies suggest that when teachers have access to scientific knowledge and base their decision-making process on scientific evidence, school results improve [18,24,25,26]. Recent studies focus on a different point of view that requires the development of democratic models of teacher professional development, where the responsibility of educating teachers is shared by schools, universities and the community [27]. In this vein, there is an increasing amount of research on Dialogic Teacher Education and its impact on schools and their communities [28,29,30]. This line of research has revealed that teacher development based on an egalitarian dialogue [30], which includes the voices of different agents involved in schools, is associated with student achievement, school improvement and community development. The Dialogic Teacher Education distinctiveness is its advocacy for a professional development based on scientific evidence, through collaboration and promotion of an open and integrative approach to the educational community functioning under the principles of dialogic learning (Table 1). Under this approach, Dialogical Pedagogical Gatherings (DPG) are one of the most extended initiatives.

Table 1.

Dialogic learning principles as frame of Dialogic Teacher Education.

1.2. Dialogical Pedagogical Gatherings

DPGs have been proposed as successful educational actions by INCLUD-ED: Strategies for inclusion and social cohesion from education in Europe Integrated project (2006–2011); the only Social and Economic Sciences research selected among the ten success stories of European research due to its added value for society. Successful Educational Actions (from now on, SEAs) are educational actions based on scientific evidence of social impact, that is, actions on teaching and learning processes that have shown improvements and these improvements are collected and published in journals of international scientific impact. SEAs are characterized by their transfer and improvement in a diversity of social contexts in which they achieve higher rates of equity and social inclusion [31,32]. The DPG is one of these SEAs identified by the Includ-ed project [15,29] aimed at teacher training. DPGs consist on collective reading and discussing meetings where participants build collective knowledge to transform their practice in education [33]. Readings are carefully selected on the scientific evidence-based criteria of “successful stories”, universal relevance and transferability to other contexts. DPGs promote reflective collaborative processes. Scholars have argued that reflection is a fundamental activity for teaching professional development [34]. In this sense, García et al. [35] suggest that promoting collaborative and dialogic reflection processes in teaching professional development allows the co-creation of knowledge based on interaction and collaboration with others. Research on DPG shows that these initiatives generate a deep reflection process that transcends the classroom [36]. Through interaction, participants express their difficulties and try to seek collective solutions drawn from the readings adapted to their own experience [37], transforming teaching into a dialogical and democratic practice [38]. The rigorous implementation of DPGs in accordance with dialogic teacher education criteria (see Table 2) are conducive of school improvement, which eventually enhance students’ learning outcomes. This action has been replicated in different locations of Spain, as well as in other countries such as England, Portugal, Mexico, Chile, Colombia and Brazil.

Table 2.

Criteria for the successful application of the Dialogic Pedagogical Gatherings.

1.3. Challenges in Educational Impact Evaluation of Professional Development of In-Service Teachers

There is a consensus in Social Science that research improves individuals’ lives. However, scientific community in social studies requires effective tools to collect evidence of this kind [39]. These limitations apply to the educational field and, particularly, to studies on teacher development. The association between teacher professional development and teaching practice with students’ outcomes has posed methodological challenges and generated strong debates among scholars [40,41]. A huge amount of teacher training is assessed by satisfaction questionnaires, instead of through the evaluation of student results and the improvement of educational communities [42,43]. For example, a review of 10 North-American studies and one English study on the impact of professional learning communities teaching practices and student learning, showed that only a small number of empirical studies explore the impact on teaching practice and student learning. Two studies provided a stronger quantitative analysis of survey and achievement data [44]. However, in recent years, teacher training evaluation focuses on successful initiatives that promote transfer from training programs to teaching practice [29,45,46,47]. Several models of teacher training evaluation exist, such as “peer evaluation revisions”, but critiques highlighted that these systems are expensive and difficult to implement due to its complex organization [47,48]. Nowadays, there is no single method available to create a complete image that relates teacher professional development and educational impact [20,49]. Based on previous theoretical contributions, we consider that educational impact is multidimensional and multifactorial, which means that it cannot be studied with a single measurement instrument [50,51,52].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Dialogic Pedagogical Gathering at Valencia ‘On Giants’ Shoulders’ as Study Object

The Dialogical Pedagogical Gathering of Valencia (DPGv) was initiated in 2011 and soon known as “On Giants’ Shoulders: Successful Educational Actions for an inclusive school”. It is still active today and it maintains its initial spirit.

The DPGv is a seminar of teacher professional development, open to diverse schools and members of the community of the Region of Valencia in Spain. It is part of continuing training external to schools in order to facilitate relations among professionals and members of different schools. The DPG has been supported by the regional government since 2011, with an annual cost of around 500 euros. This seminar gathers teachers in ten monthly meetings of 5 h each. Participation soared over the years since its beginning. The seminar started with 20 participants and after five years it gathered around 210 teachers [29]. Currently, 150 participants attend the DPGv and it has been replicated in other locations in the Valencian region.

Four criteria led us to study the DPG of Valencia: (1) it has been designed in accordance with the principles of the Dialogic Teacher Education, (2) it has been running for nine years and hence it is stable after a considerable amount of time, (3) research has already provided evidence of its impact on individual’s life and professional careers of teachers [15,29] and (4) it has been transferred to other national and international contexts.

This paper is framed within a broader research project, titled “Scientific, political and social impact of teacher professional development based on Successful Teaching Actions: the case of the Dialogic Pedagogical Gatherings ‘On Giants’ Shoulders’ at Valencia” [53].

2.2. Communicative Methodology with Social Impact

Research was conducted through a communicative methodology. The convenience of this methodology is supported by its contribution to the social impact research, its publication and open debate [32,54]. This methodological approach stablishes an equalitarian dialogue among researchers and participants of the research or end-users. It seeks consensus among existing literature, data, results and common sense of the research participants. This inter-subjectivity dialogue throughout the research process allows the emergence of a link between the research contributions and its impact upon the social context. Once these connections have been created, we can achieve greater objectivity and an increased transferability [29].

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected using six techniques that allowed to identify the DPG’s educational impact from multiple dimensions. These techniques were (1) focus group (T1), (2) semi-structured interviews (T2), (3) document analysis (T3), (4) participant observation (T4, T7), (5) in-depth interviews (T5) and (6) questionnaires (T6). Research instruments were administered to individual participants of the DPGv, as well as other key informants, such as headteachers and other managerial staff of the schools. Key informants were selected in accordance to their capacity to inform of the impact caused by the DGPv in the students.

The research process consisted of two phases of data collection and data analysis (see Table 3). In the first phase, we identified educational improvements and in the second phase, we validated the identified educational improvements from the voices of participants and identified which improvements were related to the training program. It was through the narratives of participants that we could identify which specific improvements they attributed to the DPGv.

Table 3.

Research design.

The first phase of data collection took place in school years 2014 to 2016. It consisted of a first exploration of the DPGv as a possible case of success. To do so, an analysis of the educational impact of 17 pre-primary and secondary schools was conducted. The schools were selected on the criteria that at least one teacher had participated in the DPG for three years. The document analysis included the study of the external evaluations of the educational results of these schools during the period 2013–2014–2015 (T3). We held an open focus group and all participants of the DPG were invited to join it, with an overall participation of 12 teachers (T1). Moreover, we conducted 14 semi-structured interviews with other teachers of the DPG (T2).

The second phase of the study took place in school-years 2016 to 2018, through in-depth interviews (T5) and questionaries (T6), based on a communicative approach and taking into account relevant indicators extracted from the literature [33]. For this, seven schools were selected, according to the following criteria: type of institution (public/private), number of students, educational level and years of participation in the seminars. The results and conclusions were validated by headteachers and teachers in charge of these schools. Participant observation was carried out throughout the research period (T4).

In order to conduct a multilevel analysis to identify the educational impact of the DPGv, our research considers the “Indicators for the evaluation of the scientific, political and social impact in teacher education” [33].

The selection of these indicators is carried out, on one side, after the criteria for analyzing social impact available at Sior [55] and, on the other side, following two relevant studies about education and teacher professional development in the European context, Include-ed (2006–2011) and HerstCam (2009–2013). In Table 4, there is a selection of the criteria we used in the present study to evaluate the educational impact of teacher training. In this part of the study, we take as a reference the indicators of Block A on the evaluation of educational impact on students and schools (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Educational impact indicators.

Hereafter, we describe how these indicators were operationalized in the research design in order to measure the educational impact.

The learning improvement index (A.1) was measured through a longitudinal analysis of the schools’ direct score in the standard external evaluations conducted by the regional Government for years 2013, 2014 and 2015. School results in these evaluations were analyzed for instrumental subjects such as Spanish and Valencian language, as well as Mathematics for primary schools; and Spanish, Valencian and English as well as Mathematics for secondary schools. These results allowed us to observe whether there was an improvement in direct points after teachers in the school participated in the DPGv.

Second, the percentage of improvement of social inclusion (A.2) was measured by comparing the student achievement on the evaluation with the social-economic and cultural index of the families of the schools (SECI). If schools obtained a better achievement index than expected for its SECI, we would be able to conclude that it would have contributed with higher levels of social and educational inclusion for their students.

We measured educational impact on schools upon the percentage of transfer from the training program to school (A.3) and the percentage of transfer of SEAs to teaching in school (A.4). Through our questionaries and in-depth interviews, we were able to identify, on one side, whether the school was applying DPG thanks to some teachers taking part in the DPGv. Then, schools show to what extent SEAs in which teachers had been trained in the DPGv were transferred to teaching practice, whether in a cross-curricular way or rather within a particular subject and by a particular teacher. We asked whether the school was applying at least two SEAs in at least 75% of the groups in the school. We further asked about each of the teachers taking part in the training program and what they applied in their teaching practice.

Finally, according to the communicative approach of our research, we also considered the narratives of those participating in the research, in order to provide scientific meaning and support to the training that we were trying to assess [56,57,58]. Given that we know that educational impact is the result of multidimensional and multifactorial effects, these narratives allow us to find out which and how far are the educational improvements achieved and whether these were caused by the DPGv [59].

2.4. Ethics

All participants (teachers) have agreed to provide the members of the research team with relevant information to achieve the research objectives. The different participants have been informed about the purpose of the research, they have volunteered to take part in research, as well as they have been informed about the confidential use of the collected data, exclusively used for the purposes of the research. They were provided with documented informed consent. The set of ethical procedures established by the European Commission (2013) for EU research, the data protection directive 95/46/EC and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2000/C364/01) have been followed and complied with. The study “Educational Impact Evaluation of Professional Development of In-Service Teachers: The Case of the Dialogic Pedagogical Gatherings at Valencia ‘On Giants’ Shoulders’” was fully approved by the Ethics Board of the Community of Researchers on Excellence for All (CREA) (The Ethics Board was composed of Dr. Marta Soler (president), who has expertise in the evaluation of projects from the European Framework Programme of Research of the European Union and of the European projects in the area of ethics; Dr. Teresa Sordé, who has expertise in the evaluation of projects from the European Framework Programme of Research and is a researcher in the area of Roma studies; Dr. Patricia Melgar, a founding member of the Catalan Platform Against Gender Violence and a researcher in the area of gender and gender violence; Dr. Sandra Racionero, a former secretary and member of the Ethics Board at Loyola University Andalusia (2016–2018) and a review panel member for COST action proposals in the area of health; Dr. Cristina Pulido, an expert in data protection policies and child protection in research and communication and a researcher in communication studies; and Dr. Esther Oliver, who has expertise in the evaluation of projects from the European Framework Programme of Research and is a researcher in the area of gender violence).

3. Results

Hereafter, we present the analysis of results, according to the indicators of educational impacted presented in the previous section. Here, we will describe whether schools taking part in the study improve and how they rate in every indicator (see Table 4 above) and whether these indicators correlate among them in the different schools we have assessed. As an example, we will address whether schools that have improved to a larger extent in their learning outcomes according to external evaluations do also transfer SEAs to classes and teachers’ dialogic training to the schools or not. In our case study, the narratives of teachers are used to assess to what extent improvement in learning outcomes and social inclusion can relate to teachers joining DPGv.

3.1. Educational Impact on Students

Previous research has shown that schools implementing SEA improved their results significantly [32]. Similarly, we observed an improvement on students’ learning outcomes in several schools prompted by teachers who changed their teaching practice as a result of their learning in DPG. In Table 5, we portray a summary of the main information we gathered from the 17 schools included in our study, collected by documentary analysis and questionnaires. We observed two main improvements on students as a result of teacher participation in DPGv: (1) in learning outcomes and (2) in social inclusion. Next, we describe these two findings.

Table 5.

Educational and social impact description of the DPG at the schools.

3.1.1. Improvement of Students’ Learning Outcomes

Table 5 shows relevant changes in external school evaluation tests and instrumental areas (math and language) on the 17 schools analyzed (see Table 5, columns 2, 3, 4, 5) during the years 2013, 2014 and 2015. The information collected was analyzed according to the following criteria: all evaluated subjects’ marks improve, all evaluated subjects’ marks worsen, students improve their results in some of the subjects and, finally, students obtain worse results in some of the subjects. The data indicate that half of the schools had improved in both instrumental areas, while none had obtained worse results on these (see Table 5, columns 2 and 3). Moreover, of the two areas evaluated, 16 schools had improved in one area of the external evaluation and eight schools had decreased in one area of external evaluation (see Table 5, column 3 and 4).

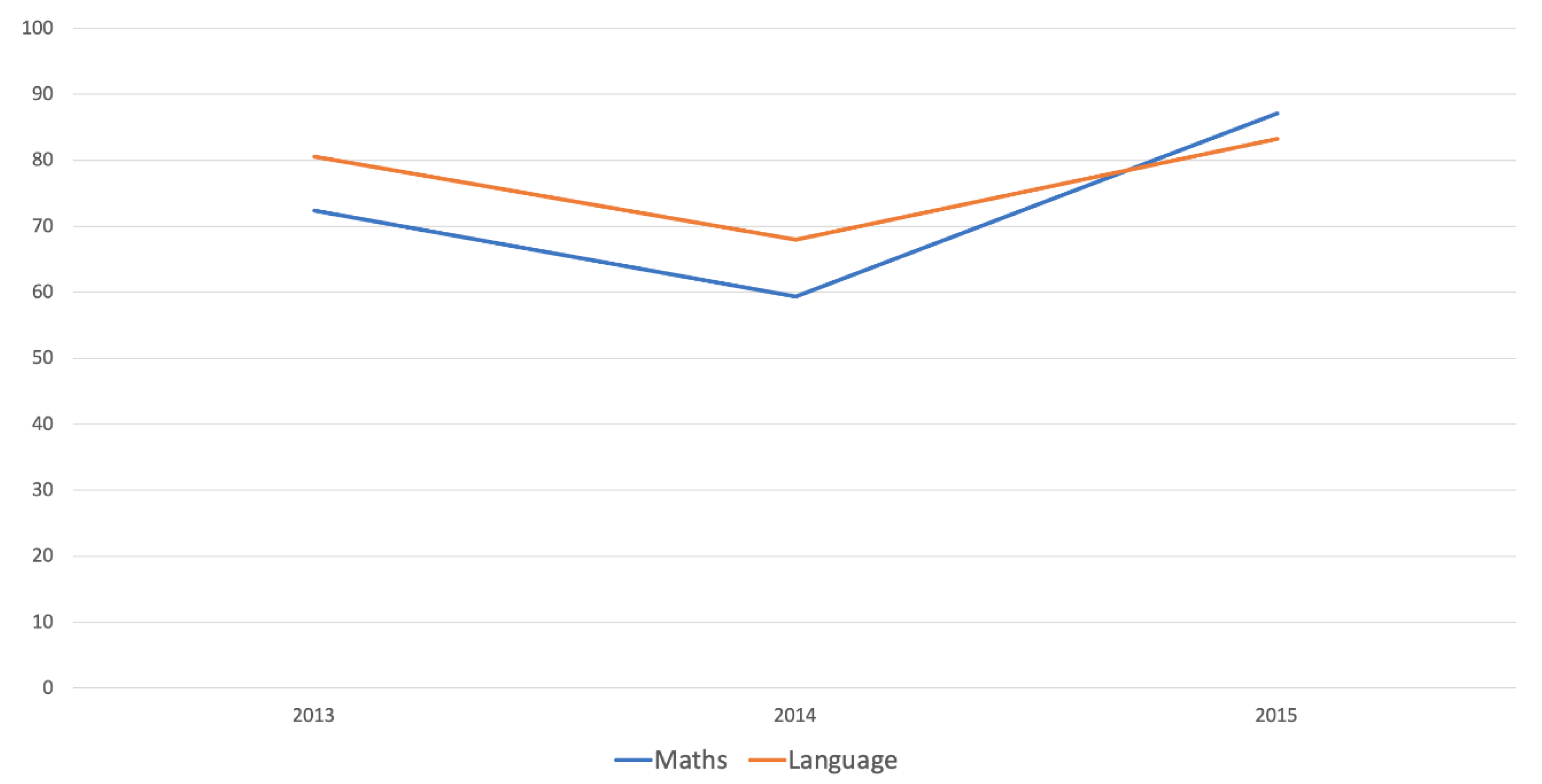

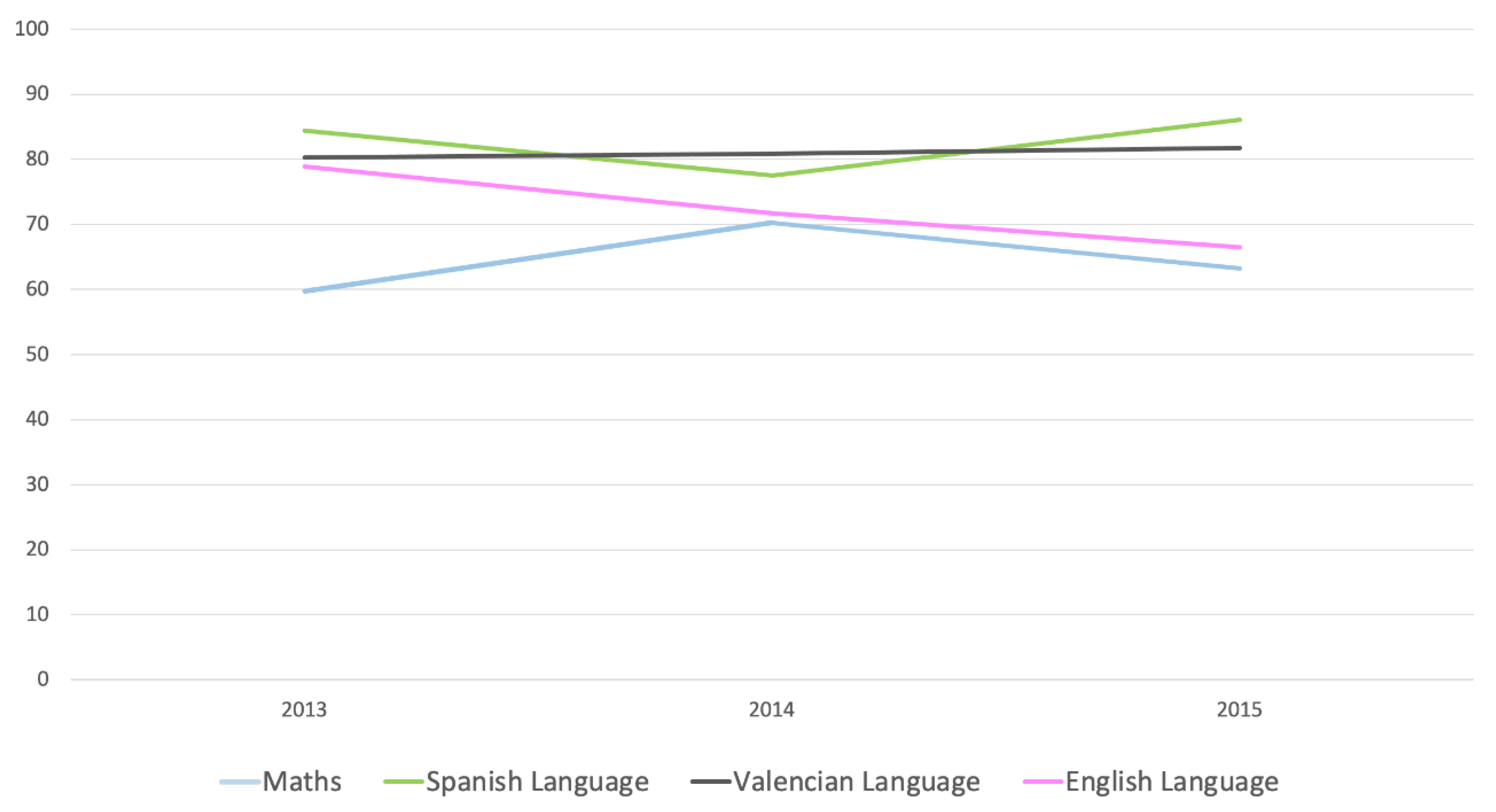

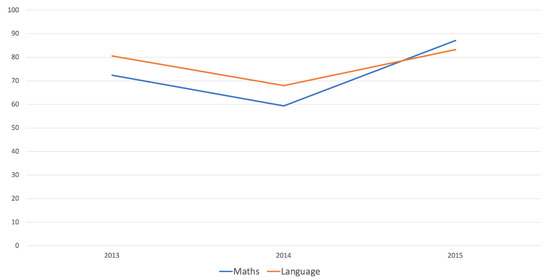

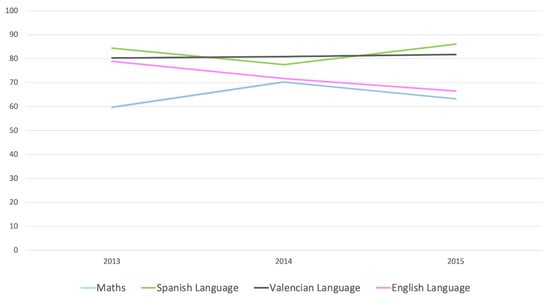

Teachers highlighted that this improvement might be due to having had applied similar dialogical spaces of teacher development to those learned at the DPGv at their schools. Another factor addressed by teachers is that transfer of SEA should be rigorous and sustained in schools to produce observable results. For example, our results show external evaluation tests of a pre- and primary education school (C3-12) and a secondary education school (C3-17). Along the years, these two schools had made the biggest change and advancement in improving educational results (see Figure 1 and Figure 2) since joining the DPG in school year 2013/2014. We can observe these improvements on Figure 1 and Figure 2 that show the school average of learning outcomes on external evaluations during three years. The figures show the school results on external evaluation on each area measured through the total number of correct answers on the test, where the highest score is 100.

Figure 1.

Educational impact pre-school and primary education of school C3-12.

Figure 2.

Educational impact secondary education of school C3-17.

As we show in Table 5, both schools entail all aspects indicated by teachers for promoting educational improvement: members of the management team and a significant number of teachers participated in the DPGv throughout the years, teachers transfer the dialogic training to the school and teachers transfer SEA to their classroom from the beginning. The results obtained in two of the analyzed areas (see Figure 2) decreased due to a lack of transfer of SEA to the school in these subjects in that period, as the director and teachers of the school C3-17 explained.

“Before we started with the successful educational actions, the results started to fall, but that year a large group of teachers started the training in the seminar and at the time we started to make successful educational actions, the tendency begins to rise again in several subjects. But not in all the subjects the successful educational actions have been transferred … it goes step by step… For me what it is really shocking is how before starting with the successful educational actions, we had about 30% of the classes empty, but three years later there are no vacancies, we are completely full”(Interview_ teacher C3-12)

“The increase in results along these years is related to the seminar because despite ours being a school with an inclusive tradition, we succeeded in improving our results. What is happening to us? We used to have very good people and people with very bad results, therefore the average was very mediocre. What happens now in the school is that good students keep obtaining good results, while the average is increasing from below. This has a lot to do with applying SEAs and with the culture of inclusive education the school has achieved, to which the DPGv has contributed widely”(In-depth interview_ school headteacher team C3-17)

Two other schools (C5-3 and C3-14) showed improvements in the results of the third-grade tests of 2015. The schools’ headteacher argued that this result relates to the transference of the SEA to the school at that moment. One of the directors explained:

“I first started in the seminar in the committee on special education needs and that was relevant to me. Even though I used to know some SEAs, the readings and deep reflections that were shared there made me change many aspects of my practice. As I am a pre-school teacher, many of the expectations I had about children, particularly about specific children, had to change. My new viewpoint and the security I achieved in the seminar were useful for them to improve … absolutely … I have seen much impact upon students, in their results … and I did not use to care about results before that… I did not care about that, just about the process of each of the children … so that each one could reach what he/she could, and I did not care more”(In-depth interview _ school headteacher C3-14)

3.1.2. Social Inclusion Improvement

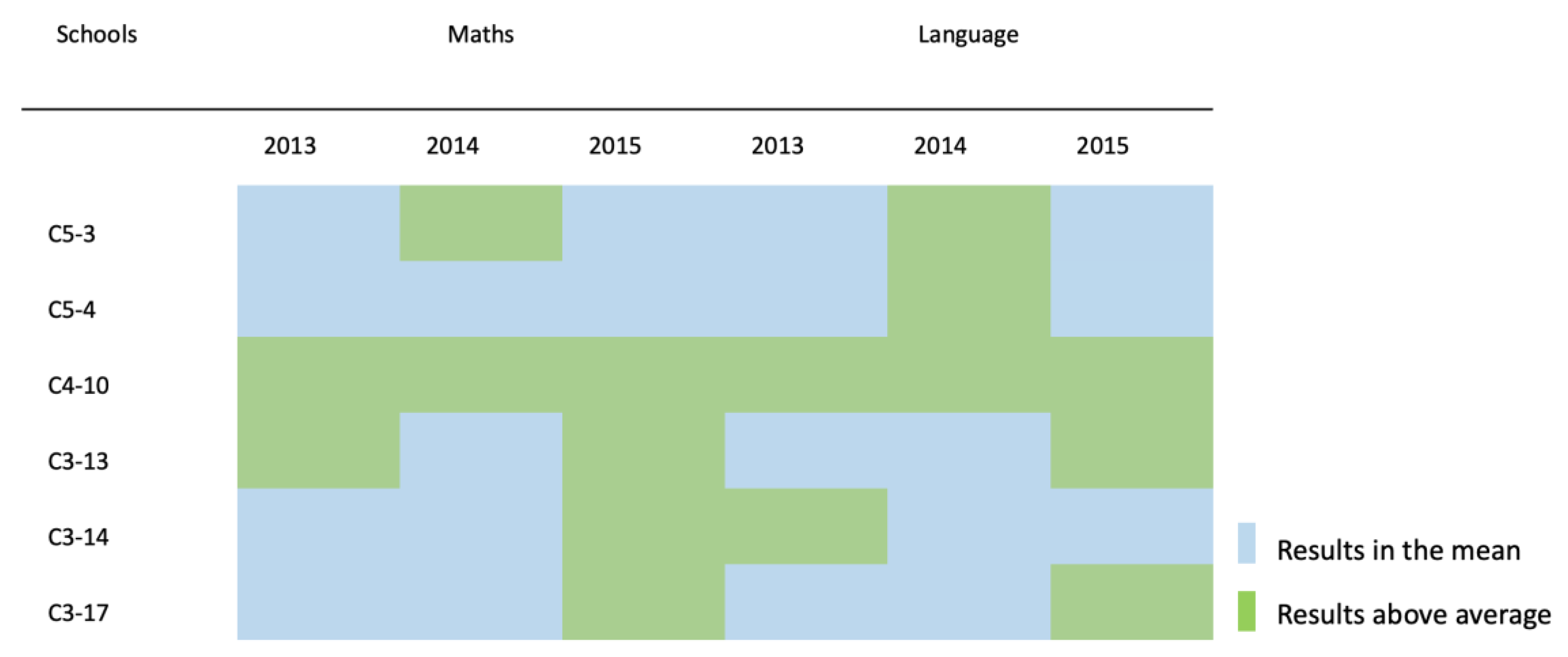

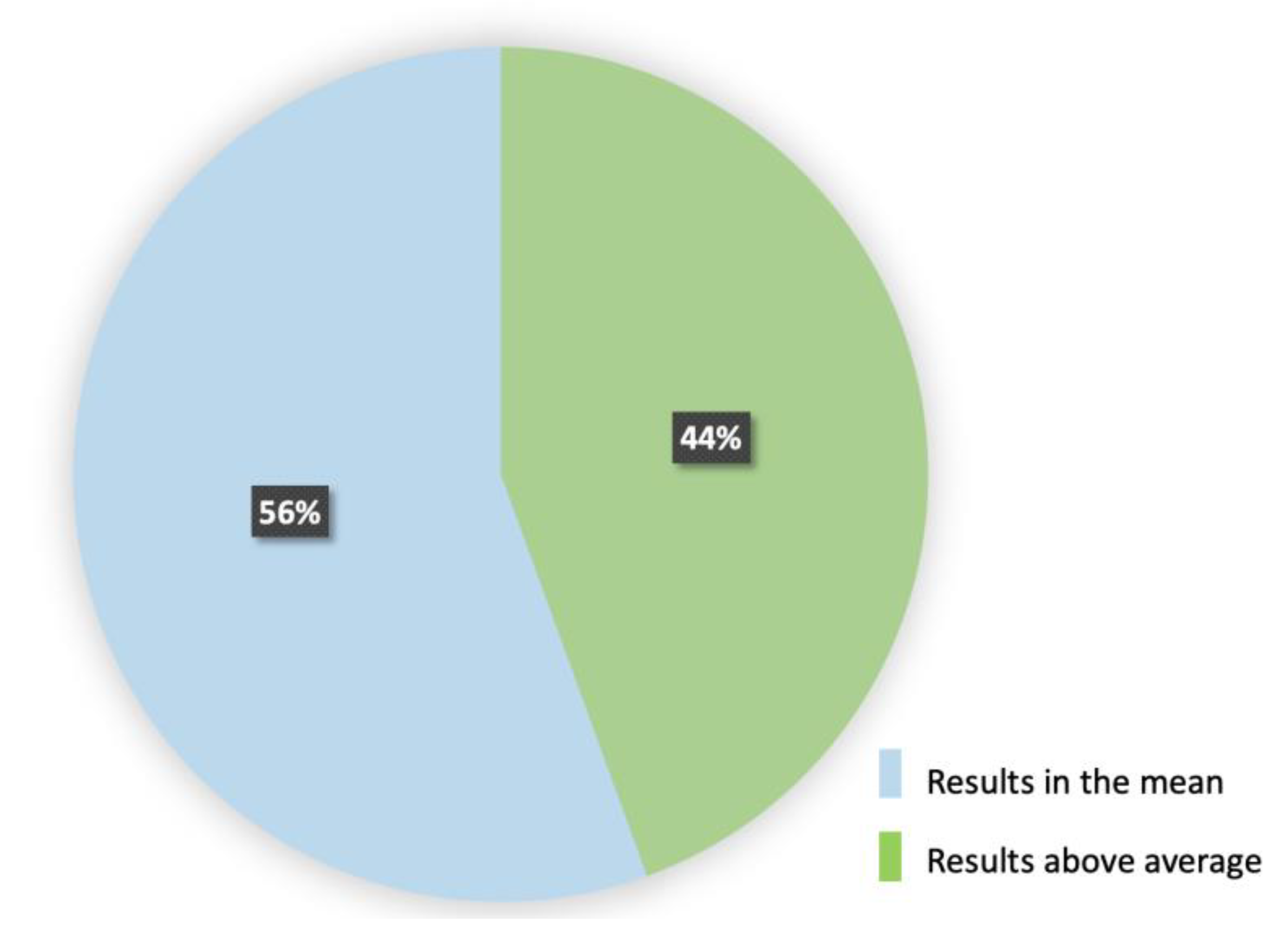

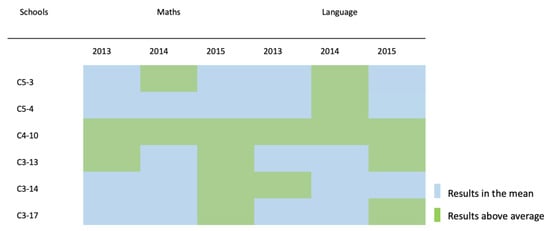

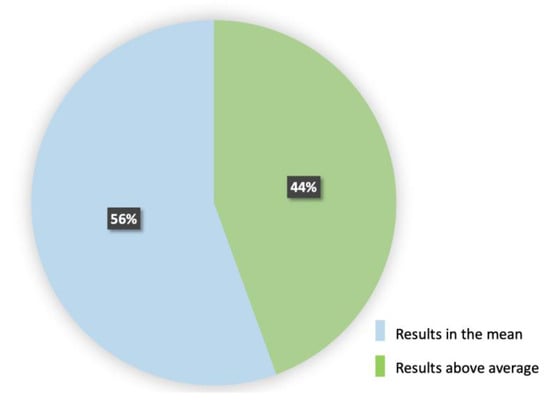

We collected information on the percentage of improvement in social inclusion from only six schools out of the 17 selected. We did not have access to this information of the other eleven schools. This information was not public, nor was it available to educational communities. The six schools from which we had information of the social inclusion had obtained higher educational results than the estimated mean for those with similar socioeconomic backgrounds for the region in at least one year of the study period. Five of these schools had obtained better results on the percentage of improvement in social inclusion in more than one learning area or in more than one standardized test (standardized test is performed annually). The school C5-4 had obtained better results in comparison to the index ISEC in one of the evaluated areas and in one evaluation year (2015) (see Figure 3). Of the data collected, approximately half of the schools showed results in accordance with the average established for schools with the same index SECI in the Valencian Community and another half show better results than those established by their reference average. In none of the cases did the schools perform below average (see Figure 4). In this sense, these schools showed improvements in terms of social inclusion in the evaluated period. The teachers and management team of the analyzed schools identify this improvement with the start of their participation in the DPGv. All these schools had a member of the headteacher team as participants at the DPGv. The improvements were observed after they transferred to their schools the DPGs and SEAs in which they were trained in the DPGv. A sixth-grade teacher explained:

Figure 3.

ISEC Results.

Figure 4.

Percentage of ISEC results.

“Despite the great diversity, despite serving the needs of students with great difficulties, through help and dialogue … even when we were not in Interactive Groups, we help each other, no matter who the students are, no matter the difficulties they have. And it is showing up in their results and so we are told by high school teachers when they receive our students”.[In-depth interview _ Teacher C4-16]

3.2. Educational Impact on Schools

Previous research exists on teaching competence improvement as a result of the participation in the DPGv, both in terms of professional competence [29] as well as in personal coherence [15]. However, DPGv’s impact on teachers is not analyzed on this study. Our study shows the impact generated in the schools in which the teaching staff who had attend the DPGv worked. Therefore, the indicators taken as reference are the transfer of teachers’ dialogic training to the school and the transfer of successful educational actions to the school (see Table 4).

In the first focus group, teachers indicated the DPGv was a rigorous and scientific teaching development initiative and never before they had participated in that kind of initiative, neither during their initial nor continuing training. Teachers expressed they perceived great professional empowerment as a result of having participated in the DPGv to transfer SEAs to the school.

“The seminar has given me the security to start literary gatherings and interactive groups. I am enjoying it like never before, every day I make an effort to improve, and I see my students with better eyes”[Teacher _ Focus Group 2014 C5-3]

Table 5 shows that all schools in the study had transferred SEAs as a result of their participation in the DPGv. In this sense, a greater number of students had been benefiting from these actions. One Pre- and Primary School and one Secondary School (C5-4 and C4-16), both showing special difficulties and result improvements, explain their success as a result of setting high expectations for their students and by seeking higher results than the average for the region. In addition, we point to the commitment of the school management team in the school C4-16 to the application of the SEA in all educational levels as well as in the transfer of the DPG to the school.

“Everything we are addressing in the DPGv about solidarity, illusion to improve education for all kids … is very important, as you want to transfer it to your school, here. Little by little, we have achieved it, we are changing the way we relate to each other, to support ourselves, to share what we do, materials … to support each other to work upon SEAs, to assess our results, to share what we have done in the DPGv, and we do that here too …”.[In-depth interviews _ headteacher C4-16]

The commitment of the school management team is another key factor of success of the DPGv. A greater impact on the educational results is noted when the school management team is committed to the transfer of what they learnt at the DPGv to the rest of the school. The following schools are good example of the transfer of learning: C5-2, C5-4, C5-16, C4-8, C3-11, C3-12, C3-17 (see Table 5).

Transfer of learning was observed under two conditions: when a member of the school management team participates in the DPGv or when supports the application of what teachers learnt in the initiative. Both types conditions generated better educational results and transference of the SEA in the schools.

For example, the head of the school C5-16, who did not participate in the DPGv while his/her colleagues did, indicated in an interview:

“I did not attend to the DPG, Mireia went, another teacher… and Mireia’s participation at the seminar [DPGv] has been key, because I as a headteacher, in my leadership and educational task, it has helped me a lot to have that scientific background… and when you share it… Well, at the beginning there were hesitations from all sectors… because there is so much people that works the other way, segregating… Having Mireia has provided us all the scientific knowledge that enables us to support… and explain the transformation in a better way. I would say to my colleagues that all who want to come along with or those who want to lead a pedagogical change towards success, I would say, go there, go there, because it will help you a lot”[In-depth interview _ school headteacher C5-16]

4. Discussion

Teacher professional development is at the centre of debates on educational polices and there is great consensus that quality teaching is a key element in educational improvement [1,13,14,20]. Our research has presented an in-depth analysis of the educational impact of the DPG carried out at the region of Valencia since 2011. DPGs are considered a SEA that incorporate relevant theoretical and scientific contributions from teacher professional development research. Moreover, DPGs take into account learning and teaching dialogic principles, whose impact on education has been widely analyzed at an international level in educational improvement and social inclusion [31]. This in-depth study contributes with new knowledge to the international debate on the link between teacher training and educational improvement. Specifically, our study focuses on teacher professional development based on evidence and its association with social and educational improvement of schools and the evaluation its impact. The research, following a communicative approach, has analyzed the educational impact of the DPGv at 17 schools from a multidimensional perspective.

There are significant challenges in understanding more precisely how teacher education affects teachers’ ability to promote student learning [20,49,60]. No single method is available to create a complete picture that relates teacher professional development and educational impact. In this sense, the educational impact indicators at different levels allow an orientation of the evaluation and promotion of teacher training actions in coherence with the international debate on teacher training and its impact on educational improvement [33]. The in-depth analysis of this first study case in the period 2014–2018 contributes with evidence that could be useful for future teacher development actions, as well as for the evaluation of these actions. This study case highlights key elements for assuring the improvement of students’ and schools’ educational and social outcomes. First, it reveals that teacher professional development should be based on scientific evidence and on SEA in order to improve educational as well as social results. Second, the commitment of the head teaching team with the DPG increases the application of the SEA in schools. Third, the transfer of the DPG to schools seems to have an effect on the improvement of students’ outcomes. These transformative elements, identified by communicative research, can help guiding future experiences of teacher professional development in order to consolidate students’ educational success.

Regarding educational impact evaluation, there is a very important shift in the measurement of teacher training from teacher satisfaction questionnaires towards the evaluation of the transferability of actions, as well as its incidence in improving results in educational communities [6,16,61,62]. Linking teacher training with student educational outcomes has always been a challenge subject to methodological debates both about what is the most appropriate to measure and about how the measurements can be designed so that they are as standardized as possible [63]. Our research shows that standardized tests can be appropriate tools to measure the impact of evidence-based teacher professional development. In the schools analyzed here, there is a higher index of improvement in educational outcomes. In this case, further studies taking a longitudinal approach could offer better evidence of the association between the schools’ participation on the DPG and the improvement of children’s outcomes. Likewise, in a long-term study it would be interesting to include other relevant indicators of educational improvement, such as the percentage of students who repeat a grade, the graduation rate and the rate of early school leaving. Other important issue is the inclusion social index of the participating schools in the DPGs. The sample used for our study is small and not representative, though it shows an improvement in the six schools. This indicator is a key element for aligning the contribution of the DPG to the 2030 agenda for Sustainable Development Educational Goals and for promoting improvement-oriented research to the students’ social and educational outcomes.

Finally, our study shows that in-service professional development programs based upon scientific evidence and dialogic principles such as the DPG have a positive effect on the improvement of students’ educational and social outcomes, though in different degrees depending on other influential factors. In the future, it would be worth to analyze the recurrence of these factors and their implications when designing teacher training actions that seek educational impact [64].

Taking into account the limitations presented, this study takes a step in the search and measurement of the educational impact on the continuing training of teachers. This research provides a first attempt on how to evaluate teacher training oriented to improve children’s lives, as well as the educational community as a whole.

5. Conclusions

The aim of our study was to apply a multilevel model of educational impact evaluation of a continuing teacher training program. We focused on a case study of the Dialogic Pedagogical Gathering in Valencia (DPGv). The DPGv is based on scientific evidence and on the dialogic principles. We observed two types of educational impact after teachers participated in the DPGv. On the one hand, our research revealed an impact on students’ educational learning outcomes and social inclusion. The findings showed that when teachers transferred to the school what they had learned in their training, there was an improvement of students’ educational learning in some of the schools. Moreover, we observed an improvement on the social inclusion indexes in the participating schools. However, we need to study further this impact to reach a conclusion on this association. On the other hand, our study showed educational impact on schools in which the head team committed to transferring the principles of the DPGv into school practices. Overall, our study highlighted the importance of taking multiple measures to assess impact of training on educational outcomes, specially the social inclusion indicator as an adequate way to align improvements with the SDG in Education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, R.F., F.M.-F. and E.R.-C.; formal analysis E.R.-C.; investigation and resources, R.F. and F.M.-F.; data curation, E.R.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.I.R.-D. and E.R.-C.; writing—review and editing, F.M.-F. and A.I.R.-D.; visualization, A.I.R.-D. and E.R.-C.; supervision, F.M.-F.; funding acquisition, R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Darling-Hammond, L. Teacher education around the world: What can we learn from international practice? Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 40, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garet, M.S.; Porter, A.C.; DeSimone, L.; Birman, B.F.; Yoon, K.S. What Makes Professional Development Effective? Results From a National Sample of Teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2001, 38, 915–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuel, W.R.; Fishman, B.J.; Yamaguchi, R.; Gallagher, L.P. What Makes Professional Development Effective? Strategies That Foster Curriculum Implementation. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 44, 921–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.J.; Grossman, P.L.; Lankford, H.; Loeb, S.; Wyckoff, J. Teacher Preparation and Student Achievement. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2009, 31, 416–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthagen, F.A.J.; Kessels, J.P.A.M. Linking Theory and Practice: Changing the Pedagogy of Teacher Education. Educ. Res. 1999, 28, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Rothman, R. Teacher and Leader Effectiveness in High-Performing Education Systems. Alliance for Excellent Education. 2011. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED517673 (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Bacher-Hicks, A.; Chin, M.; Hill, H.; Staiger, D. Explaining Teacher Effects on Achievement Using Measures from Multiple Research Traditions; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- COM. Report on Efficiency and Equity in European Education and Training Systems; Committee on Culture and Educatio: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- COM. Improving the Quality of Teacher Education; Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Embedding Professional Development in Schools for Teacher Success. Teaching in Focus. 2015. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5js4rv7s7snt-en.pdf?expires=1530135505&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=993316698F1EC10CF7F719D56B47DBF2 (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Asia Society. Improving Teacher Quality Around The World: The International Summit on the Teaching Profession (Final Report); Metlife Foundation & Pearson Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Opfer, V.D.; Pedder, D. Conceptualizing Teacher Professional Learning. Rev. Educ. Res. 2011, 81, 376–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, A.J.; Yoon, K.S.; Zhu, P.; Cronen, S.; Garet, M.S. Experimenting with Teacher Professional Development: Motives and Methods. Educ. Res. 2008, 37, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, G.M.T.; Cutanda, L.M.T. La formación continuada del profesorado de enseñanza obligatoria: Incidencia en la práctica docente y el aprendizaje de los estudiantes. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado 2017, 21, 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Flecha, R. Successful Educational Actions for Inclusion and Social Cohesion in Europe; Metzler, J.B., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L. Constructing 21st-Century Teacher Education. J. Teach. Educ. 2006, 57, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, G.; Hodgson, A.; Johnson, J.; Oancea, A.; Pring, R.; Spours, K.; Wilde, E.; Wright, S. The Nuffield Review of 14–19 Education and Training. Annual Report 2005-06. University of Oxford Department of Educational Studies: Oxford, UK. Available online: http://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/sites/default/files/files/2005-06%20annual%20report(1).pdf (accessed on 10 March 2016).

- Toom, A.; Kynäslahti, H.; Krokfors, L.; Jyrhämä, R.; Byman, R.; Stenberg, K.; Maaranen, K.; Kansanen, P. Experiences of a Research-based Approach to Teacher Education: Suggestions for future policies. Eur. J. Educ. 2010, 45, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, E.A. The economic value of higher teacher quality. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2011, 30, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.N.; Sass, T.R. Teacher training, teacher quality and student achievement. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D. Teacher-Led Development Work: A Methodology for Building Professional Knowledge, Hertscam Occasional Papers April 2013, HertsCam Publications. 2013. Available online: www.hertscam.org.uk (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Montalvo, J.; Gorgels, S. Calidad del profesorado, calidad de la enseñanza y aprendizaje: Resultados a partir del TEDS-M. [Quality of teachers, quality in teaching and learning: Results based on the TEDS-M.]. TEDS-M. Estudio internacional sobre la formación inicial en matemáticas de los maestros. Informe Español. 2013, 2, 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, J.M.E.; González, M.T.G.; Entrena, M.J.R. Los Contenidos De La Formación Continuada Del Profesorado: ¿Qué Docentes Se Están Formando? Educación XX1 2017, 21, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlberg, P. The Professional Educator: Lessons from Finland. Am. Educ. 2011, 35, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Alton-Lee, A. (Using) evidence for educational improvement. Camb. J. Educ. 2011, 41, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, D.S.; Saville, B.K.; Baker, S.C.; Marek, P. Evidence-based teaching: Tools and techniques that promote learning in the psychology classroom. Aust. J. Psychol. 2013, 65, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zeichener, K. Preparing Teachers for the 21st Century; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Carrion, R.; Virgili, U.R.Y.; Gomez, A.; Molina, S.; Ionescu, V. Teacher Education in Schools as Learning Communities: Transforming High-Poverty Schools through Dialogic Learning. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2017, 42, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.A.; Condom-Bosch, J.L.; Ruiz, L.; Oliver, E. On the Shoulders of Giants: Benefits of Participating in a Dialogic Professional Development Program for In-Service Teachers. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, A.; Garcia, C.; Racionero, S.; Racionero-Plaza, S. El aprendizaje dialógico. Cultura y Educación 2009, 21, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carrión, R.; de Aguileta, G.L.; Padrós, M.; Ramis-Salas, M. Implications for Social Impact of Dialogic Teaching and Learning. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler, M. 2017. Achieving Social Impact; Sociology in the Public Sphere Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, R.F.; Campos, E.R.; De Aguileta, G.L. Scientific Evidence-Based Teacher Education and Social Impact. In Encyclopedia of Teacher Education; Metzler, J.B., Ed.; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zeichner, K.M. Rethinking the Connections Between Campus Courses and Field Experiences in College- and University-Based Teacher Education. J. Teach. Educ. 2009, 61, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.C.; Campos, M.D.G.; García, L.M. La reflexión dialógica en la formación inicial del profesorado: Construyendo un marco conceptual. Perspect. Educ. 2017, 56, 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ródenas, C.A. La tertulia pedagógica dialógica en el practicum de la formación inicial de maestras y maestros. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación 2017, 73, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio, M.A.B.-D.; Álvarez, P.; Roldán, S.M. Implementing Dialogic Gatherings in TESOL teacher education. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2021, 15, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Sama, G. Dialogic leadership in learning communities. Intang. Cap. 2015, 11, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Flecha, R. Social Impact of Community-Based Educational Programs in Europe. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clotfelter, C.T.; Ladd, H.F.; Vigdor, J.L. Teacher-Student Matching and the Assessment of Teacher Effectiveness. J. Hum. Resour. 2006, 4, 778–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M.; Zeichner, K.M. (Eds.) Studying Teacher Education: The Report of the AERA Panel on Research and Teacher Education; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, R.; Ozturk, N.; Dökme, I. The views of the teachers taking in-service training about alternative measurement and evaluation techniques: The sample of primary school teachers. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 15, 2347–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kavak, N.; Yamak, H.; Bilici, S.C.; Bozkurt, E.; Darici, O.; Ozkaya, Y. The Evaluation of Primary and Secondary Teachers’ Opinions about In-Service Teacher Training. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 3507–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vescio, V.; Ross, D.; Adams, A. A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciraso, A. An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Teacher Training: Some Results from a Study on the Transfer Factors of Teacher Training in Barcelona Area. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 1776–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, J.; Lloyd, A.; Smith, M.; Bowe, J.; Ellis, H.; Lubans, D. Effects of professional development on the quality of teaching: Results from a randomised controlled trial of Quality Teaching Rounds. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 68, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molas-Gallart, J.; Salter, A.; Patel, P.; Scott, A.; Duran, X. Measuring third stream activities. In Final Report to the Russell Group of Universities; Science and Technology Policy Research Unit, University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Education Association. Transforming Teaching: Connecting Professional Responsibility with Student Learning. NEA: Washington, DC, USA Retrieved, 8, 13. Nuffield foundation (n.d.) . Available online: http://www.nuffieldfoundation.org (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Wineburg, M.S. Evidence in Teacher Preparation. J. Teach. Educ. 2006, 57, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L. What is societal impact of research and how can it be assessed? a literature survey. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2012, 64, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, L.; Chavez, R.; Harris-Roxas, B.; Burton, N. What’s in the box? Issues in evaluating interventions to develop strong and open communities. Community Dev. J. 2007, 43, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegler, M.C.; Twiss, J.M.; Look, V. Assessing Community Change at Multiple Levels: The Genesis of an Evaluation Framework for the California Healthy Cities Project. Heal. Educ. Behav. 2000, 27, 760–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Campos, E. Impacto Científico, Político y Social de la Formación del Profesorado Basada en Actuaciones Docentes de Éxito: El caso de la tertulia pedagógica dialógica “A hombros de los Gigantes” de Valencia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de Barcelon, Barcelona, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, A. New Developments in Mixed Methods with Vulnerable Groups. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2014, 8, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, E.; Scharnhorst, A.; Cabré, J.; Ionescu, V. SIOR: An Egalitarian Scientific Agora. Qual. Inq. 2020, 26, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, M.; Bruner, J. The Culture of Education. Can. J. Educ. Rev. Can. de L’éducation 2000, 25, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. Strategies of qualitative inquiry; Sage Publications: Champaign, IL, USA, 2008; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K. Interpretive Autoethnography; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Champaign, IL, USA, 2014; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Martí, T.S.; Flecha, R.; Rodríguez, J.A.; Bosch, J.L.C. Qualitative Inquiry: A Key Element for Assessing the Social Impact of Research. Qual. Inq. 2020, 26, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, M.; Thomson, S.; Cornelius, S.; Lofthouse, R.; Kools, Q.; Huber, S. Conceptualising Teacher Education for Inclusion: Lessons for the Professional Learning of Educators from Transnational and Cross-Sector Perspectives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrilla-Latas, Á.; Moriña-Díez, A. Criterios para la formación permanente del profesorado en el marco de la educación inclusiva. Revista de Educación 2006, 339, 517–539. [Google Scholar]

- Marcelo-García, C. Aprender a enseñar en la sociedad del conocimiento. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2002, 10, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Zeichner, K.M.; Conklin, H.G. Teacher Education Programs. Studying Teacher Education: The Report of the AERA Panel on Research and Teacher Education; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 645–735. [Google Scholar]

- Karacabey, M.F. School Principal Support in Teacher Professional Development. Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 9, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).