International Student Engagement for Sustainability of Leisure Participation: An Integrated Approach of Means-End Chain and Acculturation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Acculturation of International Students

2.2. Leisure for International Students

2.3. Relationship between the MEC Theory and Leisure

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Instrument

3.2. Laddering Methodology

3.3. Contents Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Description of Participants

4.2. Three Types of Acculturation

4.3. Implication Matrix

4.3.1. Bicultural Acceptance

4.3.2. Heritage Culture Maintenance

4.3.3. Bicultural Marginalization

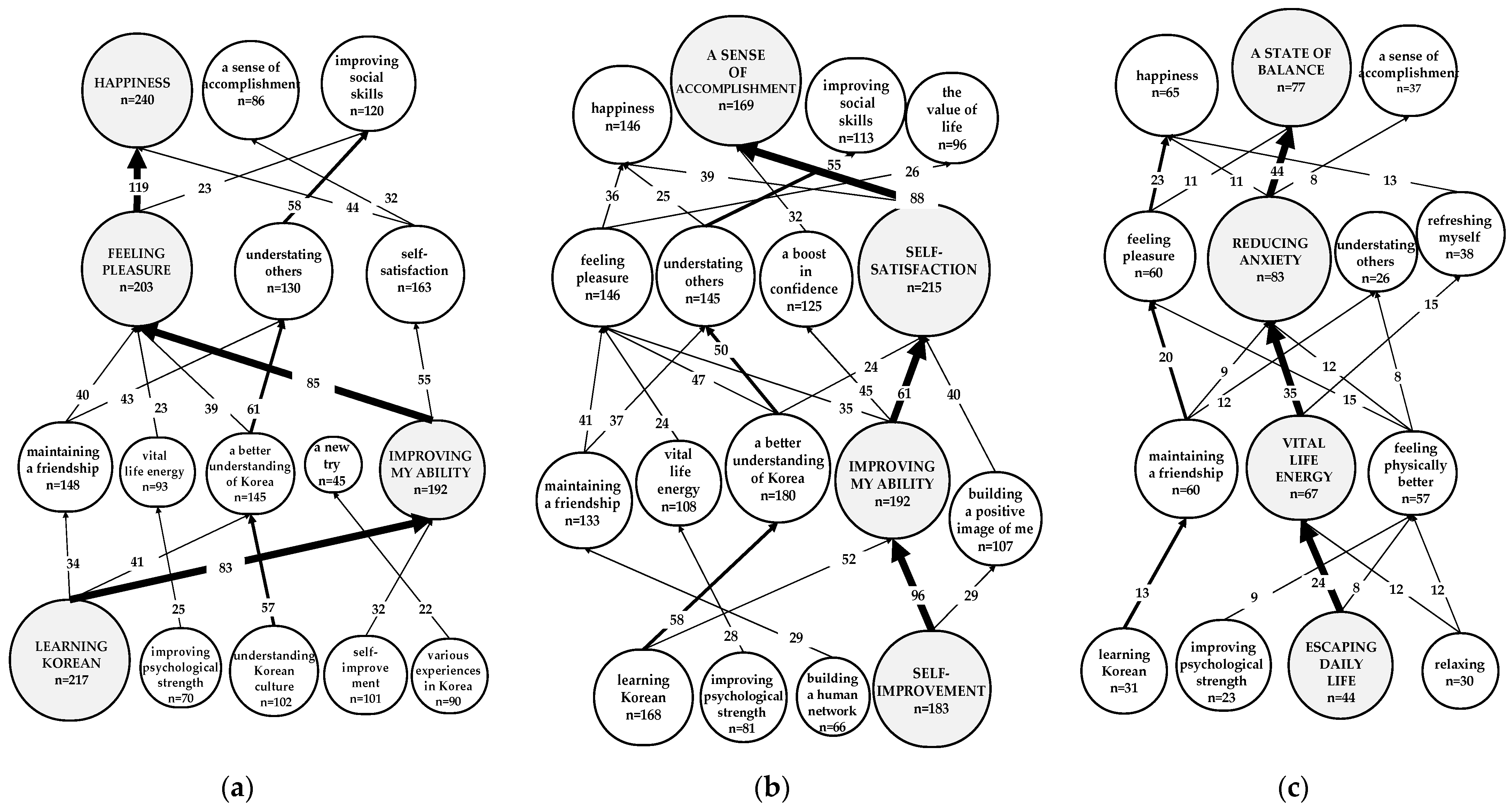

4.4. Three Types of Hierarchical Value Maps Based on Acculturation

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Edginton, C.R.; Chen, P. Leisure as Transformation, 2nd ed.; Sagamore Publishing: Champaign, IL, USA, 2008; pp. 67–121. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Da, S. The relationships between leisure and happiness-A graphic elicitation method. Leis. Stud. 2020, 39, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malysheva, S. The Rehabilitation of Idleness: The Productionof New Values and Meanings for Leisure in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries; Gaidar Institute Press: Moscow, Russia, 2019; Volume 29, p. 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, E.; Walker, G.J.; Liu, H.; Mitas, O. A cross-cultural/national study of Canadian, Chinese, and Japanese university students’ leisure satisfaction and subjective well-being. Leis. Sci. 2017, 39, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.J.; Deng, J.; Chapman, R. Leisure attitudes: A follow-up study comparing Canadians, Chinese in Canada, and Mainland Chinese. World Leis. J. 2007, 49, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Walker, G.J.; Swinnerton, G. Leisure attitudes: A comparison between Chinese in Canada and Anglo-Canadians. Leisure 2005, 29, 239–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.J.; Deng, J.; Dieser, R.B. Culture, self-construal, and leisure theory and practice. J. Leis. Res. 2005, 37, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuykendall, L.; Tay, L.; Ng, V. Leisure engagement and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, Y. How do academic stress and leisure activities influence college students’ emotional well-being? A daily diary investigation. J. Adolesc. 2017, 60, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.Y.; Yeh, W.-J.; Chen, B.T. The study of international students’ behavior intention for leisure participation: Using perceived risk as a moderator. J. Qual. Assur. Hospit. Tour. 2016, 17, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Scott, D.; Oh, C.-O. Effects of acculturation, leisure benefits, and leisure constraints on acculturative stress and self-esteem among Korean immigrants. Soc. Leis. 2005, 28, 265–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Z.; Stodolska, M. Transnationalism, leisure, and Chinese graduate students in the United States. Leis. Sci. 2006, 28, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Sung, Y.-T.; Zhou, Y.; Lee, S. The relationships between the seriousness of leisure activities, social support and school adaptation among Asian international students in the US. Leis. Stud. 2018, 37, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Stodolska, M. Acculturative stress and leisure among Chinese international graduate students. Leis. Sci. 2018, 40, 557–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.S.; Buckingham, K. Beyond communication courses: Are there benefits in adding skills-based ExcelL™ socio-cultural training? Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2007, 31, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.-C.; Sotiriadou, P.; Auld, C. An examination of the role of sport and leisure on the acculturation of Chinese immigrants. World Leis. J. 2015, 57, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W. Social capital, strategic relatedness and the formation of intraorganizational linkages. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afable-Munsuz, A.; Ponce, N.A.; Rodriguez, M.; Perez-Stable, E.J. Immigrant generation and physical activity among Mexican, Chinese & Filipino adults in the US. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1997–2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, E.H. The influence of acculturation on perception of leisure constraints of Chinese immigrants. World Leis. J. 2000, 42, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Suh, Y.I.; Kim, J. Identifying leisure constraints associated with acculturation among older Korean immigrants. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-being 2019, 14, 1655378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christenson, O.D.; Zabriskie, R.B.; Eggett, D.L.; Freeman, P.A. Family acculturation, family leisure involvement, and family functioning among Mexican-Americans. J. Leis. Res. 2006, 38, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, H. The relationships among acculturation, self-esteem, and leisure participation of foreign workers in Korea. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2010, 10, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Heo, J.M.; Lee, C.S. Exploring the relationship between types of leisure activities and acculturation among Korean immigrants. Leis. Stud. 2016, 35, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.F.; Fu, C.S. Cognitive implications of experiencing religious tourism: An integrated approach of means–end chain and social network theories. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-C.; Lin, Y.-E.; Wall, G.; Xie, P.F. A spectrum of indigenous tourism experiences as revealed through means-end chain analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 76, 103969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 46, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation and adaptation: A general framework. In Mental Health of Immigrants and Refugees; Holtzman, W.H., Ed.; Hogg Foundation for Mental Heatlh: Austin, TX, USA, 1990; pp. 90–102. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.H.; Messé, L.A.; Stollak, G.E. Toward a more complex understanding of acculturation and adjustment: Cultural involvements and psychosocial functioning in Vietnamese youth. J. Cross-Cultur. Psychol. 1999, 30, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.-P.; Hums, M.A.; Greenwell, C.T. The impact of acculturation and ethnic identity on American football identification and consumption among Asians in the United States. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2014, 15, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yan, L.; Lee, H.M.; Yang, Q. Social integration of lifestyle migrants: The case of Sanya snowbirds. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2825–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, D.T. Development of a new scale for measuring acculturation: The East Asian Acculturation Measure (EAAM). J. Immigr. Health 2001, 3, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryder, A.G.; Alden, L.E.; Paulhus, D.L. Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? A head-to-head comparison in the prediction of personality, self-identity, and adjustment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zea, M.C.; Asner-Self, K.K.; Birman, D.; Buki, L.P. The Abbreviated Multidimentional Acculturation Scale: Empirical validation with two Latino/Latina samples. Cultur. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2003, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, S.; Doucerain, M.M.; Miglietta, A.; Jurcik, T.; Ryder, A.G.; Gattino, S. The Vancouver Index of Acculturation (VIA): New evidence on dimensionality and measurement invariance across two cultural settings. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2019, 71, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J. A Comparative Study on the Acculturative Factors and Strategies of the Acculturative Level-Based International Students in Korea. Kor. Soc. Bilingual. 2017, 69, 51–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.; Zhu, C.; Meng, Q. Predicting Chinese international students’ acculturation strategies from socio—Demographic variables and social ties. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 20, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, S.-H.; Malonebeach, E.; Heo, J. Migrating to the East: A qualitative investigation of acculturation and leisure activities. Leis. Stud. 2016, 35, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grund, A.; Brassler, N.K.; Fries, S. Torn between study and leisure: How motivational conflicts relate to students’ academic and social adaptation. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, X.Y.; Cai, L.A.; Fu, X.; Chen, Y. Intercultural interactions outside the classroom: Narratives on a US campus. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2014, 55, 837–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-H.; Jang, H. How Can Marriage Immigrants Contribute to the Sustainability of the Host Country? Implication from the Leisure and Travel Patterns of Vietnamess Women in South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodolska, M.; Alexandris, K. The role of recreational sport in the adaptation of first generation immigrants in the United States. J. Leis. Res. 2004, 36, 379–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y.I.; Tsai, I.J. A Study of Differences Leisure Activities on Acculturation Types and the Effect of Leisure Activities on Leisure Satisfaction: Focusing on Internationally Married Female Immigrants. J. Tour. Sci. 2012, 36, 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Stodolska, M. Socio-cultural adaptation through leisure among Chinese international students: An experiential learning approach. Leis. Sci. 2018, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.P.; Yang, M.H. The Effect of School Adaptation Stress and Leisure-Time Exercise on School Life Maladjustment among Chinese Students in Korea. J. Mar. Sport Stud. 2016, 6, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, J. A means-end chain model based on consumer categorization processes. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-F.; Yeh, M.-Y. Means-end chains and cluster analysis: An integrated approach to improving marketing strategy. J. Target. Measur. Anal. Mark. 2000, 9, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.A.; Olson, J.C. Means-end chains: Connecting products with self. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-S.; Jeng, M.-Y.; Yeh, T.-M. The elderly perceived meanings and values of virtual reality leisure activities: A means-end chain approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; Thyne, M.; McMorland, L.-A. Means-end theory in tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 596–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mosquera, N.; Sánchez, M. The influence of personal values in the economic-use valuation of peri-urban green spaces: An application of the means-end chain theory. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Scott, N.; Tao, L.; Ding, P. Chinese tourists’ motivation and their relationship to cultural values. Anatolia 2019, 30, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.H.; Won, Y.S. Analysis on Yoga Practitioners’ Value System. Kor. J. Soc. Sport 2006, 19, 155–170. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.J. An Analysis on Leisure Value Systems Applying Means-end Chain(MEC). Kor. J. Leis. Rec. Park 2017, 41, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Valli, C. Designer-made meat and dairy products: Consumer-led product development. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2001, 72, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celenk, O.; Van de Vijver, F.J. Assessment of acculturation: Issues and overview of measures. ORPC 2011, 8, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, D.N. The Change of Personal Constructs from the Viewpoint of a Theory of Construct Implications. Ph.D. Thesis, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Tey, Y.S.; Arsil, P.; Brindal, M.; Teoh, C.T.; Lim, H.W. Motivations underlying consumers’ preference for farmers’ markets in klang valley: A means-end chain approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoli, R.; Naspetti, S. Consumer motivations in the purchase of organic food: A means—End approach. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, D.; Henchion, M. Understanding consumers’ cognitive structures with regard to high pressure processing: A means-end chain application to the chilled ready meals category. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Grunert, S.C. Measuring subjective meaning structures by the laddering method: Theoretical considerations and methodological problems. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.G.; Busson, A.; Flight, I.; Bryan, J.; Van Pabst, J.V.L.; Cox, D.N. A comparison of three laddering techniques applied to an example of a complex food choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2004, 15, 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.; Cox, D. Understanding middle-aged consumers’ perceptions of meat using repertory grid methodology. Food Qual. Prefer. 2004, 15, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botschen, G.; Thelen, E. Hard versus soft laddering: Implications for appropriate use. New Dev. App. Consum. Behav. Res. 1998, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, F.T.; Audenaert, A.; Steenkamp, J.-B.E.; Wedel, M. An investigation into the association pattern technique as a quantitative approach to measuring means-end chains. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1998, 15, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Beckmann, S.C.; Sørensen, E. Means–end chains and laddering: An inventory of problems and an agenda for research. In Understanding Consumer Decision Making: The Means-End Approach to Marketing Strategy; Olson, J.C., Reynolds, T.J., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.D.; Herrmann, A.; Huber, F.; Gustafsson, A. An Introduction to Quality, Satisfaction, and Retention—Implications for the Automotive Industry. In Customer Retention in the Automotive Industry: Quality, Satisfaction and Loyalty; Johnson, M.D., Herrmann, A., Huber, F., Gustafsson, A., Eds.; Gabler Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1997; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, T.J.; Dethloff, C.; Westberg, S.J. Advancements in Laddering, Understanding Consumer Decision Making: The Means-End Approach to Marketing and Advertising Strategy; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 91–118. [Google Scholar]

- Back, H.C.; Park, C.H.; Jang, S.Y.; Kim, J.H. Stakeholder’s Valuation of Public PMO System Using Laddering. Kor. Soc. Sim. 2015, 24, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneberg, S.C.; Gruber, T.; Reppel, A.; Ashnai, B.; Naudé, P. Complaint management expectations: An online laddering analysis of small versus large firms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2009, 38, 584–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Igbaria, M.; Iivari, J.; Maragahh, H. Why do individuals use computer technology? A Finnish case study. Inf. Manag. 1995, 29, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim Chung, R.H.; Kim, B.S.; Abreu, J.M. Asian American multidimensional acculturation scale: Development, factor analysis, reliability, and validity. Cultur. Divers. Ethn. Minor Psychol. 2004, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, T.J.; Olson, J.C. Understanding Consumer Decision Making: The Means-End Approach to Marketing and Advertising Strategy, 1st ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, R.; Baumgartner, H.; Allen, D. A means-end chain approach to consumer goal structures. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.C.; Cho, M.S.; Oh, J.S.; Seo, J.M. Relationship between the HVM and Cut-Off Level of Means-End Chain. J. Kor. Contents Assoc. 2011, 11, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, T.J.; Gutman, J. Laddering theory, method, analysis, and interpretation. J. Advert. Res. 1988, 28, 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gengler, C.E.; Reynolds, T.J. Consumer understanding and advertising strategy: Analysis and strategic translation of laddering data. J. Advert. Res. 1995, 35, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Guenzi, P.; Troilo, G. Developing marketing capabilities for customer value creation through Marketing–Sales integration. Indu. Market. Manag. 2006, 35, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenosky, D.B.; Gengler, C.E.; Mulvey, M.S. Understanding the factors influencing ski destination choice: A means-end analytic approach. J. Leis. Res. 1993, 25, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gengler, C.E.; Klenosky, D.B.; Mulvey, M.S. A Note on the Representation of Means-End Study Results; Working Paper; Rutgers University: Camden, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, S.S. Effects of Leisure Motivation on Leisure Satisfaction and Quality of Life in University Students. J. Sports Leis. Stud. 2016, 65, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, A.; Taylor, T. Sport and physical recreation in the settlement of immigrant youth. Leisure 2007, 31, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Scott, N.; Ding, P. Motivations of experienced leisure travellers: A means-end chain study on the Chinese outbound market. J. Vacat. Mark. 2019, 25, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehnke, K.; Lietz, P.; Schreier, M.; Wilhelm, A. Sampling: The selection of cases for culturally comparative psychological research. In Cross-Cultural Research Methods in Psychology; Matsumoto, D., Van de Vijver, F.J.R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonefish, T.; Kwantes, C.T. Values and acculturation: A Native Canadian exploration. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2017, 61, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, C.L.; Shmotkin, D.; Ryff, C.D. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neulinger, J. The psychology of leisure: Research approaches to the study of leisure. Springfield 1974, 11, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, O.P.; Gridneva, S.V.; Menshikov, P.V.; Kassymova, G.K.; Tokar, O.V.; Merezhnikov, A.P.; Arpentieva, M.R. Value-motivational sphere and prospects of the deviant behavior. Int.J. Educ. Inf. Tech. 2018, 12, 142–148. [Google Scholar]

- Munroe, R.L.; Munroe, R.H. Results of comparative field studies. Behav. Sci. 1991, 25, 23–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.L. Ideal affect: Cultural causes and behavioral consequences. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 2, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S.; Duffy, S.; Uchida, Y. Self as cultural mode of being. In Handbook of Cultural Psychology; Kitayama, S., Cohen, D., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 136–174. [Google Scholar]

- Glover, T.D. Leisure research for social impact. J. Leis. Res. 2015, 47, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaugeois, N.; Parker, P.; Yang, Y. Is leisure research contributing to sustainability? A systematic review of the literature. Leisure 2017, 41, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attributes | Functional Consequences | Psychological Consequences | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 learning Korean | F1 maintaining a friendship | P1 feeling pleasure | V1 happiness |

| A2 Improving psychological strength | F2 vital life energy | P2 reducing anxiety | V2 a state of balance |

| A3 understanding Korean culture | F3 feeling physically better | P3 understating others | V3 a sense of accomplishment |

| A4 building a human network | F4 economic benefits | P4 a boost in confidence | V4 improving social skills |

| A5 staff service | F5 a better understanding of Korea | P5 refreshing myself | V5 the value of life |

| A6 facility quality | F6 a new try | P6 reducing stress | V6 self-reward |

| A7 self-improvement | F7 improving my ability | P7 self-satisfaction | V7 healthy |

| A8 escaping daily life | F8 building a positive image of me | P8 a bond of sympathy | V8 self-assurance |

| A9 relaxing | |||

| A10 various experiences in Korea | |||

| A11 releasing stress | |||

| A12 sharing my heritage culture | |||

| A13 killing time |

| Characteristics | n | % | Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age | ||||

| Male | 167 | 40.2 | 18–24 | 173 | 41.7 |

| Female | 248 | 59.8 | 25–30 | 196 | 47.2 |

| Nationality | 31–36 | 37 | 8.9 | ||

| Northeast Asia | 215 | 51.8 | Over 37 | 9 | 2.2 |

| Southeast Asia | 82 | 19.5 | Program of study | ||

| Central Asia | 42 | 10.1 | BA | 107 | 25.8 |

| Europe | 40 | 9.6 | MA | 160 | 38.6 |

| America | 22 | 5.3 | Doctoral | 52 | 12.5 |

| Africa | 14 | 3.4 | Language | 96 | 23.1 |

| Length of residence | Test of Proficiency in Korean (TOPIK) | ||||

| 0 to <1 year | 110 | 26.5 | |||

| 1 to <3 years | 195 | 47.0 | None | 42 | 10.1 |

| 3 to <5 years | 91 | 21.9 | Level 1–3 | 85 | 20.5 |

| 5 + years | 19 | 4.6 | Level 4–5 | 194 | 46.7 |

| Region | Level 6 | 94 | 22.7 | ||

| Metropolitan area | 253 | 61.0 | |||

| Non-metropolitan area | 162 | 39.0 |

| Factors | N. of Item | Mean | Std. | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heritage culture maintenance | 6 | 5.179 | 0.545 | 0.884 |

| Korean culture acceptance | 6 | 4.598 | 0.434 | 0.865 |

| Dimension | Bicultural Acceptance | Heritage Culture Maintenance | Bicultural Marginalization | Total | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 171 | n = 182 | n = 62 | n = 415 | ||

| Heritage culture maintenance | 5.27 | 7.29 | 2.87 | 5.79 | 539.013 *** |

| Korean culture acceptance | 5.20 | 6.48 | 2.59 | 5.37 | 339.510 *** |

| F1 | F3 | F5 | F7 | P1 | P3 | P7 | V1 | V3 | V4 | |

| A1 | 34 | 5 | 41 | 83 | ||||||

| A2 | 6 | 25 | 1 | 10 | ||||||

| A3 | 8 | 2 | 57 | 11 | ||||||

| A7 | 11 | 11 | 3 | 32 | ||||||

| F1 | 40 | 43 | 9 | |||||||

| F3 | 23 | 2 | 11 | |||||||

| F5 | 39 | 61 | 10 | |||||||

| F7 | 85 | 10 | 55 | |||||||

| P1 | 119 | 12 | 23 | |||||||

| P3 | 21 | 14 | 58 | |||||||

| P7 | 44 | 32 | 15 |

| F1 | F3 | F5 | F7 | F8 | P1 | P3 | P4 | P7 | V1 | V3 | V4 | V5 | |

| A1 | 16 | 6 | 58 | 52 | 6 | ||||||||

| A2 | 4 | 28 | 1 | 9 | 13 | ||||||||

| A4 | 29 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 7 | ||||||||

| A7 | 18 | 7 | 4 | 96 | 29 | ||||||||

| F1 | 41 | 37 | 7 | 6 | |||||||||

| F3 | 24 | 4 | 14 | 13 | |||||||||

| F5 | 47 | 50 | 10 | 24 | |||||||||

| F7 | 35 | 11 | 45 | 61 | |||||||||

| F8 | 14 | 2 | 14 | 40 | |||||||||

| P1 | 36 | 17 | 14 | 26 | |||||||||

| P3 | 25 | 16 | 55 | 19 | |||||||||

| P4 | 17 | 32 | 14 | 8 | |||||||||

| P7 | 39 | 88 | 6 | 22 |

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F5 | P1 | P2 | P3 | P5 | V1 | V2 | V3 | |

| A1 | 13 | 2 | 3 | 5 | |||||||

| A2 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 0 | |||||||

| A8 | 3 | 24 | 8 | 2 | |||||||

| A9 | 1 | 12 | 12 | 0 | |||||||

| F1 | 20 | 9 | 12 | 3 | |||||||

| F2 | 5 | 35 | 2 | 15 | |||||||

| F3 | 15 | 12 | 8 | 7 | |||||||

| F5 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 1 | |||||||

| P1 | 23 | 11 | 4 | ||||||||

| P2 | 11 | 44 | 8 | ||||||||

| P3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | ||||||||

| P5 | 13 | 4 | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, N.; Kim, B.-S. International Student Engagement for Sustainability of Leisure Participation: An Integrated Approach of Means-End Chain and Acculturation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4507. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084507

Lee N, Kim B-S. International Student Engagement for Sustainability of Leisure Participation: An Integrated Approach of Means-End Chain and Acculturation. Sustainability. 2021; 13(8):4507. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084507

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Nahyun, and Bong-Seok Kim. 2021. "International Student Engagement for Sustainability of Leisure Participation: An Integrated Approach of Means-End Chain and Acculturation" Sustainability 13, no. 8: 4507. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084507

APA StyleLee, N., & Kim, B.-S. (2021). International Student Engagement for Sustainability of Leisure Participation: An Integrated Approach of Means-End Chain and Acculturation. Sustainability, 13(8), 4507. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084507