Industrial Heritage Tourism as a Driver of Sustainable Development? A Case Study of Steirische Eisenstrasse (Austria)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Peripheral Industrial Regions and Industrial Heritage Tourism—Challenges and Opportunities

2.1. Regional Development of Peripheral, (Old) Industrial Regions in Europe

2.2. Elements of Industry-Based Cultural Heritage

2.3. Sustainable Development and Industrial Heritage Tourism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodological Approach

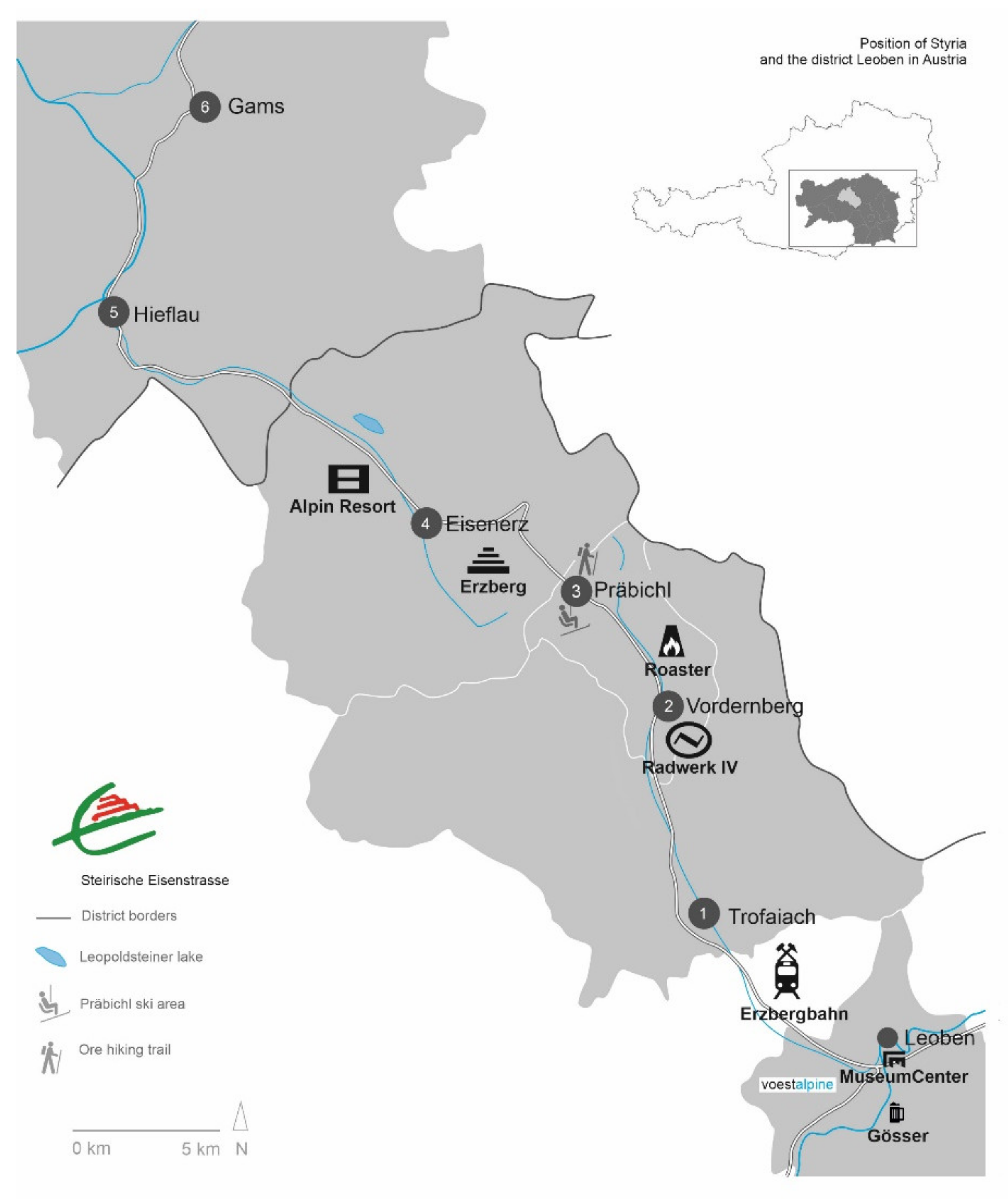

3.2. Case Study—Steirische Eisenstrasse (Styrian Iron Route)

4. Results

4.1. Tourism and Industrial Heritage Assets

- Tourism Profile

- 2.

- Leoben, MuseumCenter, and the Montanuniversität

- 3.

- Eisenerz and Erzberg—Flagship Projects

- 4.

- Other Industrial Heritage Sites and Events

4.2. Valorizing Industrial Heritage via Network-Based Management

5. Discussion—Impacts of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Regional Development

5.1. Utilizations of Industrial Heritage

5.2. Governing Industrial Heritage (Tourism)

5.3. Industrial Heritage Tourism and Sustainable Regional Development

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Álvarez-García, J.; Maldonado-Erazo, C.P.; Del Río-Rama, M.C.; Castellano-Álvarez, F.J. Cultural Heritage and Tourism Basis for Regional Development: Mapping of Scientific Coverage. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradin, K.; Hammer, T. Making the Most of World Natural Heritage—Linking Conservation and Sustainable Regional Development? Sustainability 2016, 8, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykogianni, E.; Airaghi, E.; Krohn, C.; Vanhoutte, C. Material Cultural Heritage as a Strategic Territorial Development Resource: Mapping impacts through a set of common European socio-economic indicators. In Working Paper; ESPON EGTC: Luxembourg, 2019; ISBN 978-99959-55-98-4. [Google Scholar]

- Petronela, T. The Importance of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Economy. Proc. Econ. Financ. 2016, 39, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Introducing Cultural Heritage into the Sustainable Development Agenda. Sessions 3A and 3A-a. Background Note prepared by Giovanni Boccardi and Cécile Duvelle. 2013. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CLT/images/CulturalHeritageFinalENG.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- UNESCO. Third UNESCO World Forum on Culture and Cultural Industries Culture, Creativity and Sustainable Development. Research, Innovation, Opportunities (Florence Declaration). 2014. Available online: http://www.lacult.unesco.org/docc/ENG_Florence_Declaration_4oct.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- ICOMOS. ICOMOS Action Plan: Cultural Heritage and Localizing the Sustainable Development Goals. 2017. Available online: www.icomos.org/en/focus/un-sustainable-development-goals/76821-cultural-heritage-and-sustainable-development-2 (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Kapila, D.S. Paradigm Shifts in Global Heritage Discourse. Space Commun. 2015, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrosława, W.-M. Cultural heritage and development: UNESCO’s new paradigm in a changing geopolitical context. Third World Q. 2019, 40, 1593–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, C. CONSERVATION 3.0 Cultural Heritage as a driver for regional growth. Sci. Res. Inf. Technol. 2019, 9, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society*Faro, 2005. Treaty Series-No. 199. Available online: www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/199 (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- EU Commission. Towards an Integrated Approach to Cultural Heritage for Europe. COM(2014) 477. 2014. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2015-0293_EN.html (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- EU Commission. European Framework for Action on Cultural Heritage Working Paper. 2019. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/5a9c3144-80f1-11e9-9f05-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Bertacchin, E.; Segre, G. Introduction: Culture, sustainable development and social quality: A paradigm shift in the economic analysis of cultural production and heritage conservation. City Cult. Soc. 2016, 7, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, M.; Cappellano, F. Linking Cultural Heritage to Smart Specialisation Strategies. Technical Report ROCK Project -Regeneration and Optimization of Cultural Heritage in Creative and Knowledge Cities. H2020-SC5-2016-2017 GA 730280. 2020. Available online: www.rockproject.eu/documents-list/download/445/linking-cultural-heritage-to-smart-specialisation-strategies (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- Naldi, L.; Nilsson, P.; Westlund, H.; Wixe, S. What is smart rural development? J. Rural Stud. 2015, 40, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavolová, H.; Bakalár, T.; Emhemed, E.M.A.; Hajduová, Z.; Pafčo, M. Model of sustainable regional development with implementation of brownfield areas. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2019, 6, 1088–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, J.; Neuts, B. Territorial capital, smart tourism specialization and sustainable regional development: Experiences from Europe. Habitat Int. 2017, 68, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ache, P. Cities in old industrial regions between local innovative milieu and urban governance reflections on city region governance. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2000, 8, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, R.; Shin, D.-H. The restructuring of old industrial areas in Europe and Asia. Environ. Plan. A 2005, 37, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.S.; Porter, M.E. Changing global industry leadership: The case of shipbuilding. In Competition in Global Industries; Porter, M.E., Ed.; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1986; pp. 539–568. [Google Scholar]

- Baeten, G.; Swyngedouw, E.; Albrechts, L. Politics, institutions and regional restructuring processes: From managed growth to planned fragmentation in the reconversion of Belgium’s last coal mining region. Reg. Stud. 1999, 33, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, B.; Finka, M.; Lintz, G. (Eds.) Rise and Decline of Industry in Central and Eastern Europe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, G. Contested terrain: Mining and the environment. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2004, 29, 205–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, G.; Franz, M.; Edwards, D.; Pahlen, G.; Nathanail, P. The challenge of sustainability: Incentives for brownfield regeneration in Europe. Environ. Sci. Policy 2007, 10, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, P.; Mayer, H. Small Town Sustainability: Economic, Social, and Environmental Innovation, 2nd ed.; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- VanLeeuwen, E.S. Urban–Rural Interactions. Towns as Focus Points in Rural Development; Physica: Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatek-Sołtys, A.; Mainet, H.; Wiedermann, K.; Édouard, J. (Eds.) Small and Medium Towns’ Attractiveness at the Beginning of the 21st Century; Presses Universitaires Blaise Pascal: Clermond-Ferrand, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, M. (Ed.) Bright Future for Black Towns -Economic Performance and Place-Based Characteristics of Industrial Regions in Europe. Technical Report BRIGHT FUTURE Project. 2017. Available online: www.researchgate.net/publication/325195233_Economic_performance_and_place-based_characteristics_of_industrial_regions_in_Europe (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Erickcek, G.; McKinney, H. Small cities blues: Looking for growth factors in small and medium-sized cities. Econ. Dev. Q. 2006, 20, 232–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benneworth, P.; Clifton, N.; Doucet, B.; Goebel, C.; Hamm, R.; Schmitz, Y. The Regeneration of Image in Old Industrialised Regions: Agents of Change and Changing Agents; Cuvillier: Göttingen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Suchacek, J. The role of selected soft factors in the transformation of old industrial regions. J. Econ. Manag. Bus. 2009, 15, 114–124. [Google Scholar]

- Harfst, J. Utilizing the past: Valorizing post-mining potential in Central Europe. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2015, 2, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, C. The post-2013 reform of EU cohesion policy and the place-based narrative. J. Eur. Public Policy 2013, 20, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfst, J.; Wirth, P.; Marot, N. Utilizing endogenous potentials through EU cohesion policy: Examples from Central Europe. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 2193–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjup-Kavčič, M.; Režun, B.; Eržen, U.; Peljhan, M.; Mulec, I. Natural, cultural and industrial heritage as a basis for sustainable regional development within the Geopark Idrija project (Slovenia). Geogr. Pannonica 2010, 14, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storrank, B. Unlocking Regional Potentials Nordic Experiences of Natural and Cultural Heritage as a Resource in Sustainable Regional Development. TemaNord No521. Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görmar, F.; Harfst, J.; Simic, D.; Wust, A. The Transformative Power of Industrial Culture from Concepts to Actions; Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde and Institut für Geographie und Raumforschung: Graz, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sutestad, S.; Mosler, S. Industrial Heritage and their Legacies: “Memento non mori: Remember you shall not die”. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 225, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glorius, B.; Manz, K. Beyond the City of Modernism: A counter-narrative of industrial culture. GeoScape 2018, 12, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfst, J.; Simic, D. Industrial Culture as an emerging topic in regional development? In Proceedings of the 2017 International Geobalkanica Conference, Skopje, Northern Macedonia, 20–21 May 2017; pp. 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Somoza-Medina, X.; Monteserín-Abella, O. The Sustainability of Industrial Heritage Tourism Far from the Axes of Economic Development in Europe: Two Case Studies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overmann, H.; Mieg, H. (Eds.) Industrial Heritage Sites in Transformation: Clash of Discourses, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harfst, J.; Wust, A.; Nadler, R. Conceptualising Industrial Culture. Gesoscapes 2018, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S. Sustainable Development, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development Our Common Future (Brundtland Report). 1987. Available online: www.are.admin.ch/dam/are/en/dokumente/nachhaltige_entwicklung/dokumente/bericht/our_common_futurebrundtlandreport1987.pdf.download.pdf/our_common_futurebrundtlandreport1987.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2020).

- Thatcher, A. Theoretical definitions and models of sustainable development that apply to human factors and ergonomics. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Human Factors in Organizational Design and Management and the 46th Annual Nordic Ergonomics Society Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, 17–20 August 2014; pp. 747–752. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areschoug, S. Representations of (Im)mobile Young Masculinities and Place in the Swedish Countryside. Boyhood Stud. 2019, 12, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimt, A. Searching for continuity and connections: Narratives of belonging from a post-industrial city. City Cult. Soc. 2014, 5, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Braun, E.; Petersen, S. Branding the destination versus the place: The effects of brand complexity and identification for residents and visitors. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otgaar, A. Industrial Tourism. Opportunities for Cities and Enterprise; Ashgate: Farnham Surrey, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, P.F. Industrial Heritage Tourism, 1st ed.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hospers, G.-J. Industrial Heritage Tourism and Regional Restructuring in the European Union. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2002, 10, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppila, P.; Saarinen, J.; Leinonen, R. Sustainable Tourism Planning and Regional Development in Peripheries: A Nordic View. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2009, 9, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Jang, S. The tourism–economy causality in the United States: A sub-industry level examination. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rivero, M.; Cárdenas-García, P.-J. Population characteristics and the impact of tourism on economic development. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 615–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, J. Tourism, smart specialisation, growth, and resilience. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Iankova, K. Strategies and Challenges of Tourist Facilities Management in the World Heritage Site: Case of the Maritime Greenwich, London. Tour. Anal. 2012, 17, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, N. Planning for Urban Heritage Places: Reconciling Conservation, Tourism, and Sustainable Development. J. Plan. Lit. 2003, 17, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Kalandides, A. Rethinking the place brand: The interactive formation of place brands and the role of participatory place branding. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2015, 47, 1368–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Erfgen, C. Let them do the work: A participatory place branding approach. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2014, 7, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Posch, A.; Steiner, G.; Risopoulos, F. Die Erzherzog-Johann-Fallstudie ein Inter und Transdisziplinäres Lehr und Forschungsprojekt der Kulturlandschaftsforschung; Österreichisches Bundesministerium für Bildung: Wien, Austria, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ortner, L. Die Steirische Eisenstrasse Von Eisenerz bis Altenmarkt: Regionalstrukturen und Regionalentwicklung unter besonderer Berücksichtigung räumlicher Disparitäten. Master’s Diploma Thesis, University of Graz, Graz, Austria, 2009. Available online: https://unipub.uni-graz.at/obvugrhs/206934 (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Zimmermann, F.M.; Janschitz, S. Erfolgs und Misserfolgsfaktoren bei der Umstrukturierung von Traditionellen Bergbaugebieten. Das Beispiel Eisenerz/Österreich. In Neue Landschaften, Bergbauregionen im Wandel; Dokumentation des Fachkongresses auf der Euregia 2004 in Leipzig; Sächsisches Staatsministerium des Innern, Ed.; Sächsisches Staatsministerium des Inneren: Dresden, Germany, 2004; pp. 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, W.; Harfst, J. Heritage-based Products for Tourism something to write home about? In Creativity, Culture and Tourism in the Urban and Regional Development; Ježek, J., Dusek, J., Slach, O., Eds.; University of West Bohemia: Pilsen, Czech Republic, 2014; pp. 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzera, J.; Osebik, D. Strategic Destination Management in an Alpine Mining Region Adventure Sports Tourism as Chance for Image Transformation. In Post-Mining Regions in Central Europe. Problems, Potentials, Possibilities; Wirth, P., Černič Mali, B., Fischer, W., Eds.; Oekom: Munich, Germany, 2012; pp. 212–225. [Google Scholar]

- Landesstatistik Steiermark. Heft10/2019 Sommertourismus. Graz, Austria. 2019. Available online: https://www.landesentwicklung.steiermark.at/cms/dokumente/12658765_142970621/2fa4b470/Heft%2010-2019%20Sommertourismus%202019-Internet.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Landesstatistik Steiermark. Tourism Fact Sheet Leoben. Graz. 2020. Available online: https://www.verwaltung.steiermark.at/cms/dokumente/12208857_117401915/4d434236/611_Leoben.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Fischer, W.; Harfst, J.; Simic, D. Exkursion zur Steirischen Eisenstraße -Teil 1: Von Trofaiach auf den Präbichl. GeoGraz 2016, 59, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- WKO. Steirische Regionalpolitische Studien, Nr. 03/2013, Standortstudie Obersteiermark Ost 2013+. Graz. 2013. Available online: www3.wkstmk.at/iws/Studien/STUDIE%2003_2013-WEB.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- WKO. Beschäftigtenstatistik 2020, Graz. 2020. Available online: https://www.wko.at/service/stmk/zahlen-daten-fakten/Beschaeftigtenstatistik_der_gewerblichen_Wirtschaft_Steierm.html (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Statistik Austria. Abgestimmte Erwerbsstatistik Zeitreihe zur Erwerbstätigkeit ab 2009. Statcube (Q). Available online: https://www.statistik.at/web_de/services/statcube/index.html (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- SPOT. Survey (Forthcoming): Technical Report on Tourism Survey-Case study Steirische Eisenstrasse; University of Graz: Graz, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, W.; Harfst, J.; Pizzeria, J.; Simic, D. Exkursion zur "Steirischen Eisenstraße Teil 2: Von der Stadt Eisenerz bis Gams. Geograz 2017, 60, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Harfst, J.; Wirth, P. Zur Bedeutung endogener Potenziale in klein- und mittelstädtisch geprägten Regionen Überlegungen vor dem Hintergrund der Territorialen Agenda 2020. Raumforsch. Und Raumordn. 2014, 72, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LAG Steirische Eisenstraße. Die Lokale Entwicklungsstrategie der LEADER-Region Steirische Eisenstraße 2014-2020: High Tech versus High Feeling. LEADER Strategie Steirische Eisenstrasse. 2014. Available online: www.steirische-eisenstrasse.at/lokale-entwicklungsstrategie/eu-periode-2014-2020/ (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Meffert, H. Strategien des Markenmanagements. In Markenmanagement; Meffert, H., Burmann, C., Koers, M., Eds.; Gabler Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2002; Volume 1, pp. 135–162. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinelli, C. Competition, Cooperation, Co-opetition. Widening the Perspective on Place Branding. Ph.D. Thesis, Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy, 2012. Available online: http://europa2020.spiruharet.ro/fisiere/Diplomatie%20publica/Marketing%20international/Place%20Branding/Compwtition%20Place%20branding.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Kraus, F.; Merlin, C.; Job, H. Biosphere reserves and their contribution to sustainable development. Z. Für Wirtsch. 2014, 58, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, C. Brownfields Redevelopment and the Quest for Sustainability. Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag. 2009, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano-Álvarez, F.J.; del Río-Rama, M.d.l.C.; Álvarez-García, J.; Durán-Sánchez, A. Limitations of Rural Tourism as an Economic Diversification and Regional Development Instrument. The Case Study of the Region of La Vera. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šťastná, M.; Vaishar, A.; Brychta, J.; Tuzová, K.; Zloch, J.; Stodolová, V. Cultural Tourism as a Driver of Rural Development. Case Study: Southern Moravia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Roders, A.; Van Oers, R. Wedding cultural heritage and sustainable development: Three years after. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 4, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocca, F. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harfst, J.; Sandriester, J.; Fischer, W. Industrial Heritage Tourism as a Driver of Sustainable Development? A Case Study of Steirische Eisenstrasse (Austria). Sustainability 2021, 13, 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073857

Harfst J, Sandriester J, Fischer W. Industrial Heritage Tourism as a Driver of Sustainable Development? A Case Study of Steirische Eisenstrasse (Austria). Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073857

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarfst, Jörn, Jasmin Sandriester, and Wolfgang Fischer. 2021. "Industrial Heritage Tourism as a Driver of Sustainable Development? A Case Study of Steirische Eisenstrasse (Austria)" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073857

APA StyleHarfst, J., Sandriester, J., & Fischer, W. (2021). Industrial Heritage Tourism as a Driver of Sustainable Development? A Case Study of Steirische Eisenstrasse (Austria). Sustainability, 13(7), 3857. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073857