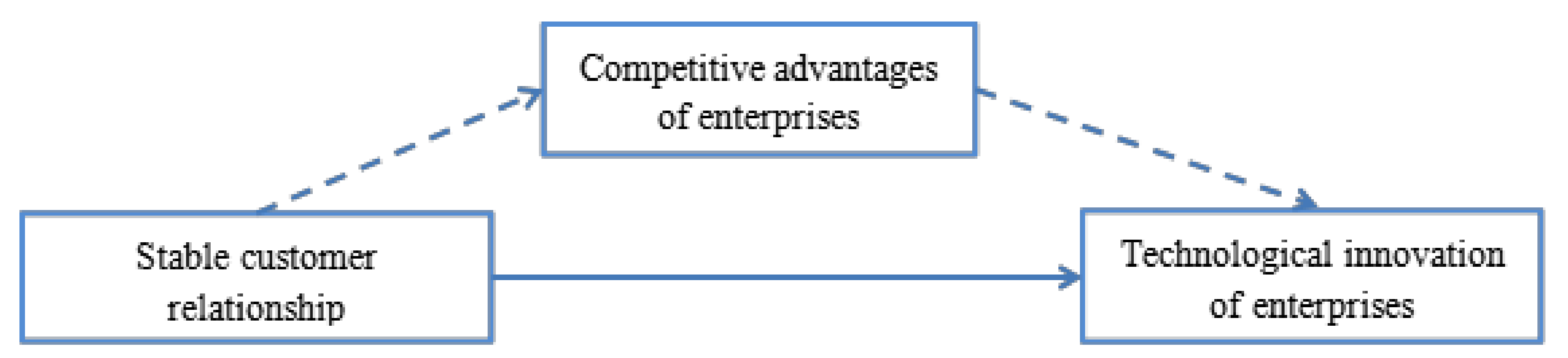

The Impact of Stable Customer Relationships on Enterprises’ Technological Innovation Based on the Mediating Effect of the Competitive Advantage of Enterprises

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Relevant Literature on the Technological Innovation of Enterprises

2.2. Relevant Literature on Competitive Advantages of Enterprises

3. Theoretical Analysis and Development of Hypotheses

3.1. Theoretical Analysis

3.2. Development of Hypotheses

4. Research Design

4.1. Sample Selection and Data Source

4.2. Variables

4.3. Methodological Remarks

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Regression Result Analysis

5.2.1. Customer Stability and Technological Innovation

5.2.2. Analysis of the Intermediary Effect: Enterprise Competitive Advantage

5.3. Further Analyses

5.3.1. Firm size

5.3.2. Property Rights

5.3.3. Enterprise Age

5.3.4. Capital Intensity

6. Robustness Test

6.1. Variable Index Replacement

6.2. Exclusion of Alternative Hypothesis

6.3. Sub-Sample Test

6.3.1. Eliminate the Samples of Enterprises with a Low Proportion of Customer Sales

6.3.2. Eliminating the Samples of Enterprises Whose Main Customers Are Individuals

6.4. The Solution of the Endogenous Problem: Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.; Yang, L.X.; Xin, F. Does real estate hinder Chinese innovation? An interpretation based on the loan term structure of the financial system. Manag. World 2016, 6, 64–80. [Google Scholar]

- Aghion, P.; Reenen, J.V.; Zingales, L. Innovation and institutional ownership. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 277–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Dang, Y. Corporate governance and innovation: Differences among industry categories. Econ. Res. J. 2014, 6, 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- An, H.; Chen, C.R.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, T. Corporate innovation: Do diverse boards help? J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2019, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.H.; Fang, J.X. “National Team” shareholding and firms’ innovation decisions. Stud. Int. Financ. 2020, 8, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L.; Shen, R.; Zhang, B. Does the media spotlight burn or spur innovation? Rev. Acc. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Tian, X. The dark side of analyst coverage: The case of innovation. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 109, 856–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; David, P.-C.; Anna, T.-S. Firms’ innovation strategy under the shadow of analyst coverage. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 131, 456–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Fu, K.; Low, A.; Zhang, W. Non-executive employee stock options and corporate innovation. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 115, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemmanur, T.J.; Kong, L.; Krishnan, K.; Yu, Q. Top management human capital, inventor mobility, and corporate innovation. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2019, 54, 2383–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.X.; Weathers, J. Employee treatment and firm innovation. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2019, 46, 977–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.T.; Sun, M. Innovation activities in Chinese manufacturing firms: The roles of firm ownership and CEO incentives. Econ. Res. J. 2010, 5, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, L.H.; Lerner, J.; Wu, C. Intellectual property rights protection, ownership, and innovation: Evidence from China. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2017, 30, 2446–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Pan, J.P.; Dai, Y.Y. Litigation risk, judicial local protectionism and innovation. Econ. Res. J. 2015, 3, 131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, A.; Singh, M.; Aldokas, A. Do corporate taxes hinder innovation? J. Financ. Econ. 2017, 124, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemmanur, T.J.; Tian, X. Do anti-takeover provisions spur corporate innovation? A regression discontinuity analysis. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2018, 53, 1163–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Hsu, P.H.; Li, K.; Zhang, J. The real effect of smoking bans: Evidence form corporate innovation. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2020, 55, 387–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.H.; Tian, X.; Xu, Y. Financial development and innovation: Cross-country evidence. J. Financ. Econ. 2014, 112, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornaggia, J.; Mao, Y.; Tian, X.; Wolfe, B. Does banking competition affect innovation? J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 115, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, V.; Baghai, R.; Subramanian, K. Wrongful discharge laws and innovation. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2014, 27, 301–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhong, T.; Lee, J.Y. Capacity reduction pressure, financing constraints, and enterprise sustainable innovation investment: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patatoukas, P.N. Customer-base concentration: Implications for firm performance and capital markets. Account. Rev. 2012, 87, 363–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennifer, I. Customers and cash: How relationships affect suppliers’ cash holdings. J. Corp. Financ. 2013, 19, 159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, P.; Park, S.S.; Yildizhan, C. Customer-Base Concentration, Profitability and Distress Across the Corporate Life Cycle. MPRA Paper. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/53941/ (accessed on 26 February 2014).

- Campello, M.; Gao, J. Customer concentration and loan contract terms. J. Financ. Econ. 2016, 3, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, D.A.; Li, B. Customer-base concentration, profitability and the information environment: The U.S. government as a major customer. Account. Rev. 2020, 95, 101–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yang, Z.C. Customer relationship and debt contracting. Working Paper. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, X. Does stable relationship with customers improve the analyst forecasts about suppliers? J. Financ. Res. 2016, 5, 156–172. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Nie, J. Research on relationship between market power and independent innovation performance: Take telecommunication industry as an example. Sci. Sci. Manag. Sci. Technol. 2011, 32, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sougiannis, T. The accounting based valuation of corporate R&D. Acc. Rev. 1994, 69, 44–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, P.H. Technological innovations and aggregate risk premiums. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 94, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, S.; Wasley, C.E.; Zach, T. The effect of research and development (R&D) inputs and outputs on the relation between the uncertainty of future operating performance and R&D expenditures. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2011, 26, 121–144. [Google Scholar]

- Manso, G. Motivating innovation. J. Financ. 2011, 66, 1823–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Clulow, V.; Gerstman, J.; Barry, C. The resource-based view and sustainable competitive advantage: The case of a financial services firm. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2003, 27, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, W.D. The Effect of International Corporate Strategies and Information and Communication Technologies on Competitive Advantage and Firm Performance: An Exploratory Study of the International Engineering, Procurement and Construction (IEPC) Industry; The George Washington University: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sol, P.D.; Kogan, J. Regional competitive advantage based on pioneering economic reforms: The case of Chilean FDI. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2007, 38, 901–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coff, R.W. Human assets and management dilemmas: Coping with hazards on the road to resource-based theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 374–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. A framework linking intangible resources and capabilities to sustainable competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 14, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B.A.; Coff, R.; Kryscynski, D. Rethinking sustained competitive advantage from human capital. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 376–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofek, E.; Sarvary, M. Leveraging the customer base: Creating competitive advantage through knowledge management. Manag. Sci. 2001, 47, 1441–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tallman, S.; Jenkins, M.; Henry, N.; Pinch, S. Knowledge, clusters, and competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.N.; Roman, R.A. Did TARP banks get competitive advantages? J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2015, 50, 1199–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.H.; Bao, G.M. Study on the Relation of the integrity of corporate and the competitive advantage: The empirical investigation of Suzhou 188 corporates in the six areas. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2005, 4, 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhai, S.Y.; Gu, P. The non-controlling shareholders’ activism and corporate technological innovation. China Ind. Econ. 2018, 7, 155–173. [Google Scholar]

- Macneil, I.R. Contracts: Adjustment of long term economic relations under classical, neoclassical and relational contract law. Northwestern Univ. Law Rev. 1978, 72, 854–902. [Google Scholar]

- Frydlinger, D.; Cummins, T.; Vitasek, K.; Bergman, J. Unpacking Relational Contracts: The Practitioner’s Go-To Guide for Understanding Relational Contracts. Available online: http://www.vestedway.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Unpacking-Relational-Contracting_v19 (accessed on 10 February 2019).

- Brahm, F.; Tarzijan, J. Relational contracts and collaboration in the supply chain: Impact of expected future business volume on the make-or-buy decision. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 52, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hamel, G. The core competence of the corporation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 68, 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, L.; Yin, S. Green innovation risk identification of the manufacturing industry under global value chain based on grounded theory. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veugelers, R. Collaboration in R&D: An assessment of theoretical and empirical findings. De Econ. 1998, 3, 419–443. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.; Woodruff, C. Interfirm relationships and informal credit in Vietnam. Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 1285–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battigalli, P.; Fumagalli, C.; Polo, M. Buyer power and quality improvements. Res. Econ. 2007, 61, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.; Frow, P. A strategic framework for customer relationship management. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosman, M.; Kelly, T.; Olsson, P.; Warfield, T. The profitability and pricing of major customers. Rev. Account. Stud. 2004, 9, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J. The role of marketing capability in innovation-based competitive strategy. J. Strateg. Mark. 2003, 11, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Z.L.; Gao, Q. Market structure, market performance and innovation behavior: Based on the panel date of China’s industrial firms. Ind. Econ. Res. 2013, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Titman, S. The effect of capital structure on a firm’s liquidation decision. J. Financ. Econ. 1984, 13, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkin, D.B.; Markman, G.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Is CEO pay in high-technology firms related to innovation? Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 1118–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, B.B.; Wang, T.; Li, C.T. Credit rent-seeking, financing constraint and corporate innovation. Econ. Res. J. 2017, 5, 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.P.; Zhang, D. Impact of vertical relationship concentration and manager governance mechanism on technological innovation performance. Sci. Sci. Manag. Sci. Technol. 2016, 37, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Cui, Y.; Zheng, Y. The impact of corporate strategy on enterprise innovation based on the mediating effect of corporate risk-taking. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodgson, M. Organizational learning: A review of some literatures. Organ. Stud. 1993, 14, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Variable | Variable Definition |

|---|---|---|

| RD_S | R&D operating income ratio | R&D investment/total operating income |

| Stable1 | Customer stability (count method) | Number of top five customers in two consecutive years/5 |

| Stable2 | Customer stability (ratio method) | Total sales of stable customers/total sales of top five customers |

| Strength | Competitive advantages of firm | Profit from main business/income from main business |

| CC | Customer concentration | Total sales amount of the top five customers/total sales amount of the year |

| Lnsize | Firm size | Natural logarithm of total assets |

| Age | Firm Maturity | Duration of the company since its establishment |

| ROA | Return on assets | Net profit/total asset |

| Lev | Leverage | Total liability/total asset |

| TobinQ | Firm growth | (price per share * tradable shares + net assets per share * non tradable shares + book value of liabilities)/total assets |

| CF | Cash flow level | Corporate free cash flow/total assets |

| PPE | Capital expenditure | Cash paid for the construction of fixed assets, intangible assets and other long-term assets/total assets |

| Esh | Proportion of shares held by senior management | Senior management’s shares/total share capital |

| Bsize | Board size | Natural logarithm of total number of directors |

| Dual | Duality | The president and general manager have duality. If yes, it is 1; otherwise, it is 0 |

| Year | Year-fixed effect | Year dummies |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Max | Min | Sd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RD_S | 1173 | 0.0290 | 0.1510 | 0.0000 | 0.0251 |

| Stable1 | 1173 | 0.5270 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.2460 |

| Stable2 | 1173 | 0.6110 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.2710 |

| Strength | 1173 | 0.1950 | 0.9230 | −44.0300 | 1.3300 |

| CC | 1173 | 0.2680 | 0.9740 | 0.0128 | 0.1810 |

| Lnsize | 1173 | 22.0600 | 26.0200 | 19.2400 | 1.1230 |

| Age | 1173 | 15.1900 | 62.0000 | 3.0000 | 4.8360 |

| ROA | 1173 | 0.0434 | 0.3120 | -0.5070 | 0.0525 |

| Lev | 1173 | 0.4710 | 0.9670 | 0.0158 | 0.1830 |

| PPE | 1173 | 0.0616 | 0.4740 | 0.0006 | 0.0478 |

| CF | 1173 | 0.0033 | 0.2760 | −0.7490 | 0.1030 |

| TobinQ | 1173 | 2.3530 | 14.9300 | 0.6830 | 1.6200 |

| Esh | 1173 | 0.0311 | 0.6620 | 0.0000 | 0.0932 |

| Bsize | 1173 | 2.1840 | 2.8900 | 1.3860 | 0.2000 |

| Dual | 1173 | 0.7920 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.4060 |

| Stable1 | Stable2 | Stable1 | Stable2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Column (1) | Column (2) | Column (3) | Column (4) | |

| Stable | 0.0049 *** | 0.0047 *** | 0.0056 *** | 0.0054 *** |

| (2.74) | (2.73) | (3.21) | (3.17) | |

| CC | −0.0095 | −0.0104 * | ||

| (−1.62) | (−1.75) | |||

| Lnsize | −0.0045 * | −0.0046 * | ||

| (−1.90) | (−1.92) | |||

| Age | −0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||

| (−0.02) | (0.09) | |||

| ROA | −0.0317 * | −0.0305 | ||

| (−1.65) | (−1.59) | |||

| Lev | −0.0033 | −0.0035 | ||

| (−0.40) | (−0.43) | |||

| PPE | 0.0323 ** | 0.0327 ** | ||

| (2.11) | (2.13) | |||

| CF | 0.0047 | 0.0050 | ||

| (1.12) | (1.19) | |||

| TobinQ | −0.0009 | −0.0008 | ||

| (−1.06) | (−1.04) | |||

| Esh | −0.0319 * | −0.0311 * | ||

| (−1.84) | (−1.80) | |||

| Bsize | 0.0083 ** | 0.0083 ** | ||

| (2.06) | (2.08) | |||

| Dual | −0.0027 | −0.0026 | ||

| (−0.93) | (−0.88) | |||

| _cons | 0.0197 *** | 0.0194 *** | 0.1099 ** | 0.1099 ** |

| (15.24) | (13.79) | (2.08) | (2.07) | |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 1173 | 1173 | 1173 | 1173 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.1217 | 0.1230 | 0.1610 | 0.1626 |

| Stable = Stable1 | Stable = Stable2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RD_S | Strength | RD_S | RD_S | Strength | RD_S | |

| Column (1) | Column (2) | Column (3) | Column (4) | Column (5) | Column (6) | |

| Stable | 0.0056 *** | 0.0231 *** | 0.0049 *** | 0.0054 *** | 0.0198 *** | 0.0049 *** |

| (3.21) | (2.99) | (2.89) | (3.17) | (2.84) | (2.86) | |

| Strength | 0.0267** | 0.0265 ** | ||||

| (2.19) | (2.15) | |||||

| CC | −0.0095 | −0.0278 | −0.0088 | −0.0104 * | −0.0309 | −0.0096 |

| (−1.62) | (−1.03) | (−1.45) | (−1.75) | (−1.15) | (−1.57) | |

| Lnsize | −0.0045 * | 0.0197 * | −0.0051 ** | −0.0046 * | 0.0194 * | −0.0051 ** |

| (−1.90) | (1.68) | (−2.13) | (−1.92) | (1.67) | (−2.14) | |

| Age | −0.0000 | −0.0017 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | −0.0015 | 0.0001 |

| (−0.02) | (−0.65) | (0.08) | (0.09) | (−0.59) | (0.19) | |

| ROA | −0.0317 * | 0.7117 *** | −0.0507 ** | −0.0305 | 0.7167 *** | −0.0495 ** |

| (−1.65) | (8.29) | (−2.22) | (−1.59) | (8.29) | (−2.16) | |

| Lev | −0.0033 | −0.0098 | −0.0030 | −0.0035 | −0.0106 | −0.0032 |

| (−0.40) | (−0.37) | (−0.38) | (−0.43) | (−0.40) | (−0.41) | |

| PPE | 0.0323 ** | 0.1114 * | 0.0294 * | 0.0327 ** | 0.1121 * | 0.0297 * |

| (2.11) | (1.74) | (1.94) | (2.13) | (1.75) | (1.95) | |

| CF | 0.0047 | −0.0182 | 0.0051 | 0.0050 | −0.0169 | 0.0054 |

| (1.12) | (−1.11) | (1.23) | (1.19) | (−1.03) | (1.29) | |

| TobinQ | −0.0009 | 0.0014 | −0.0009 | −0.0008 | 0.0015 | −0.0009 |

| (−1.06) | (0.43) | (−1.13) | (−1.04) | (0.44) | (−1.11) | |

| Esh | −0.0319 * | −0.0638 | −0.0302 * | −0.0311 * | −0.0588 | −0.0295 * |

| (−1.84) | (−0.92) | (−1.71) | (−1.80) | (−0.85) | (−1.67) | |

| Bsize | 0.0083 ** | 0.0169 | 0.0078 ** | 0.0083 ** | 0.0171 | 0.0079 ** |

| (2.06) | (1.07) | (1.98) | (2.08) | (1.09) | (2.00) | |

| Dual | −0.0027 | −0.0068 | −0.0026 | −0.0026 | −0.0061 | −0.0024 |

| (−0.93) | (−0.70) | (−0.87) | (−0.88) | (−0.63) | (−0.83) | |

| _cons | 0.1099 ** | −0.2384 | 0.1163 ** | 0.1099 ** | −0.2355 | 0.1162 ** |

| (2.08) | (−0.93) | (2.25) | (2.07) | (−0.93) | (2.23) | |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 1173 | 1173 | 1173 | 1173 | 1173 | 1173 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.1610 | 0.2744 | 0.1681 | 0.1626 | 0.2736 | 0.1696 |

| Stable = Stable1 | Stable = Stable2 | Stable = Stable1 | Stable = Stable2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large-Scale | Small-Scale | Large-Scale | Small-Scale | SOE | NSOE | SOE | NSOE | |

| Column (1) | Column (2) | Column (3) | Column (4) | Column (5) | Column (6) | Column (7) | Column (8) | |

| Stable | 0.0038 * | 0.0100 *** | 0.0037 * | 0.0109 *** | 0.0046 ** | 0.0075 *** | 0.0037 * | 0.0087 *** |

| (1.86) | (3.16) | (1.80) | (3.43) | (2.24) | (2.66) | (1.81) | (3.12) | |

| CC | −0.0070 | −0.0097 | −0.0077 | −0.0104 | −0.0117 | −0.0090 | −0.0126 * | −0.0096 |

| (−0.87) | (−0.88) | (−0.94) | (−0.96) | (−1.63) | (−1.06) | (−1.71) | (−1.13) | |

| Lnsize | 0.0013 | −0.0076 * | 0.0012 | −0.0066 * | −0.0027 | −0.0057 * | −0.0028 | −0.0057 * |

| (0.43) | (−1.95) | (0.40) | (−1.73) | (−0.65) | (−1.90) | (−0.66) | (−1.89) | |

| Age | 0.0005 | 0.0175 * | 0.0005 | 0.0164 * | 0.0009 | −0.0004 | 0.0009 | −0.0003 |

| (0.77) | (1.84) | (0.85) | (1.84) | (1.05) | (−0.75) | (1.10) | (−0.58) | |

| ROA | −0.0255 | −0.0307 | −0.0246 | −0.0300 | −0.0096 | −0.0486 * | −0.0093 | −0.0450 |

| (−1.01) | (−0.95) | (−0.98) | (−0.94) | (−0.42) | (−1.71) | (−0.41) | (−1.58) | |

| Lev | −0.0174 * | 0.0181 | −0.0177 * | 0.0182 * | −0.0188 | 0.0107 | −0.0200 | 0.0122 |

| (−1.68) | (1.60) | (−1.70) | (1.67) | (−1.55) | (1.02) | (−1.63) | (1.17) | |

| PPE | 0.0021 | 0.0611 ** | 0.0023 | 0.0618 ** | 0.0116 | 0.0608 *** | 0.0119 | 0.0616 *** |

| (0.11) | (2.50) | (0.12) | (2.44) | (0.59) | (2.64) | (0.61) | (2.64) | |

| CF | 0.0069 | −0.0012 | 0.0069 | 0.0000 | 0.0125 *** | −0.0029 | 0.0132 *** | −0.0037 |

| (1.39) | (−0.16) | (1.37) | (0.00) | (2.77) | (−0.44) | (2.84) | (−0.53) | |

| TobinQ | 0.0011 | −0.0015 | 0.0011 | −0.0014 | −0.0004 | −0.0010 | −0.0004 | −0.0009 |

| (1.13) | (−1.33) | (1.14) | (−1.24) | (−0.34) | (−0.95) | (−0.37) | (−0.88) | |

| Esh | 0.0145 | −0.0330 * | 0.0170 | −0.0328 * | 0.1816 | −0.0468 ** | 0.1785 | −0.0468 ** |

| (0.27) | (−1.67) | (0.31) | (−1.70) | (0.65) | (−2.32) | (0.63) | (−2.34) | |

| Bsize | 0.0081 | 0.0058 | 0.0079 | 0.0064 | 0.0101 * | 0.0106 | 0.0101 * | 0.0108 |

| (1.44) | (1.15) | (1.42) | (1.27) | (1.91) | (1.57) | (1.91) | (1.59) | |

| Dual | −0.0027 | −0.0002 | −0.0023 | −0.0004 | 0.0018 | −0.0059 | 0.0019 | −0.0057 |

| (−0.80) | (−0.05) | (−0.71) | (−0.10) | (0.84) | (−1.35) | (0.88) | (−1.31) | |

| _cons | −0.0273 | −0.0460 | −0.0257 | −0.0559 | 0.0515 | 0.1351 ** | 0.0529 | 0.1309 ** |

| (−0.41) | (−0.32) | (−0.38) | (−0.41) | (0.53) | (2.13) | (0.54) | (2.04) | |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 638 | 535 | 638 | 535 | 607 | 566 | 607 | 566 |

| Adj−R2 | 0.2119 | 0.1846 | 0.2127 | 0.1964 | 0.2173 | 0.1746 | 0.2157 | 0.1834 |

| Stable = Stable1 | Stable = Stable2 | Stable = Stable1 | Stable = Stable2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mature | Young | Mature | Young | High Cap. Intensity | Low Cap. Intensity | High Cap. Intensity | Low Cap. Intensity | |

| Column (1) | Column (2) | Column (3) | Column (4) | Column (5) | Column (6) | Column (7) | Column (8) | |

| Stable | 0.0043 * | 0.0059 * | 0.0014 | 0.0095 *** | 0.0073 *** | 0.0037 | 0.0076 *** | 0.0036 |

| (1.90) | (1.81) | (0.69) | (3.18) | (2.94) | (1.24) | (3.44) | (1.09) | |

| CC | −0.0089 | −0.0078 | −0.0089 | −0.0101 | −0.0088 | −0.0017 | −0.0095 | −0.0023 |

| (−0.99) | (−1.03) | (−1.01) | (−1.36) | (−1.33) | (−0.20) | (−1.44) | (−0.28) | |

| Lnsize | −0.0044 | −0.0039 | −0.0043 | −0.0038 | −0.0043 | −0.0085 * | −0.0041 | −0.0086 * |

| (−1.40) | (−1.02) | (−1.39) | (−1.01) | (−1.04) | (−1.87) | (−1.01) | (−1.87) | |

| Age | 0.0004 | −0.0006 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | −0.0001 | 0.0007 | −0.0001 |

| (0.45) | (−0.46) | (0.52) | (0.03) | (0.78) | (−0.17) | (1.05) | (−0.18) | |

| ROA | −0.0106 | −0.0986 ** | −0.0096 | −0.0974 ** | −0.0453 * | −0.0287 | −0.0436 | −0.0277 |

| (−0.48) | (−2.55) | (−0.44) | (−2.53) | (−1.66) | (−0.99) | (−1.63) | (−0.95) | |

| Lev | 0.0038 | −0.0237 * | 0.0037 | −0.0231 * | −0.0073 | 0.0033 | −0.0082 | 0.0036 |

| (0.38) | (−1.88) | (0.36) | (−1.88) | (−0.85) | (0.22) | (−0.96) | (0.24) | |

| PPE | 0.0105 | 0.0513 ** | 0.0099 | 0.0535 ** | 0.0050 | 0.0699 *** | 0.0065 | 0.0692 *** |

| (0.59) | (2.30) | (0.55) | (2.43) | (0.30) | (2.75) | (0.39) | (2.73) | |

| CF | 0.0016 | 0.0100 * | 0.0020 | 0.0105 * | 0.0099 * | −0.0026 | 0.0107 * | −0.0026 |

| (0.27) | (1.72) | (0.34) | (1.81) | (1.80) | (−0.32) | (1.89) | (−0.32) | |

| TobinQ | −0.0022 ** | 0.0010 | −0.0022 ** | 0.0010 | 0.0005 | −0.0018 | 0.0004 | −0.0018 |

| (−2.40) | (0.72) | (−2.40) | (0.74) | (0.40) | (−1.43) | (0.38) | (−1.40) | |

| Esh | −0.0675 | −0.0054 | −0.0665 | −0.0071 | −0.0520 ** | −0.0628 | −0.0507 ** | −0.0632 |

| (−1.36) | (−0.31) | (−1.35) | (−0.43) | (−2.43) | (−1.49) | (−2.41) | (−1.49) | |

| Bsize | 0.0112 ** | 0.0020 | 0.0109 ** | 0.0016 | 0.0064 | 0.0089 | 0.0064 | 0.0091 |

| (2.08) | (0.28) | (2.05) | (0.23) | (1.15) | (1.51) | (1.18) | (1.53) | |

| Dual | −0.0068 | 0.0016 | −0.0066 | 0.0015 | −0.0015 | −0.0006 | −0.0011 | −0.0006 |

| (−1.61) | (0.47) | (−1.60) | (0.46) | (−0.54) | (−0.11) | (−0.42) | (−0.13) | |

| _cons | 0.0931 | 0.1227 | 0.0930 | 0.1117 | 0.1012 | 0.1895 * | 0.0950 | 0.1910 * |

| (1.29) | (1.46) | (1.29) | (1.36) | (1.21) | (1.91) | (1.15) | (1.90) | |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 691 | 482 | 691 | 482 | 634 | 539 | 634 | 539 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.1967 | 0.2189 | 0.1917 | 0.2382 | 0.2085 | 0.1714 | 0.2152 | 0.1719 |

| RD_A | RD_S | RD_A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable1 | Stable2 | Sta1dum | Sta2dum | Sta1dum | Sta2dum | |

| Column (1) | Column (2) | Column (3) | Column (4) | Column (5) | Column (6) | |

| Stable | 0.0038 *** | 0.0033 ** | 0.0027 *** | 0.0019 ** | 0.0018 *** | 0.0012 ** |

| (2.59) | (2.50) | (3.07) | (2.28) | (2.80) | (2.07) | |

| CC | −0.0049 | −0.0054 | −0.0098 * | −0.0104 * | −0.0051 | −0.0054 |

| (−1.22) | (−1.34) | (−1.68) | (−1.80) | (−1.28) | (−1.38) | |

| Lnsize | −0.0063 *** | −0.0063 *** | −0.0045 * | −0.0046 * | −0.0063 *** | −0.0063 *** |

| (−3.47) | (−3.52) | (−1.93) | (−1.92) | (−3.50) | (−3.54) | |

| Age | −0.0000 | 0.0000 | −0.0000 | 0.0000 | −0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| (−0.07) | (0.04) | (−0.10) | (0.06) | (−0.16) | (0.01) | |

| ROA | 0.0257 * | 0.0265 * | −0.0292 | −0.0298 | 0.0274 * | 0.0269 * |

| (1.74) | (1.78) | (−1.54) | (−1.57) | (1.86) | (1.83) | |

| Lev | 0.0043 | 0.0042 | −0.0030 | −0.0036 | 0.0045 | 0.0041 |

| (0.90) | (0.87) | (−0.37) | (−0.44) | (0.94) | (0.86) | |

| PPE | 0.0168 | 0.0169 | 0.0320 ** | 0.0308 ** | 0.0166 | 0.0158 |

| (1.35) | (1.36) | (2.08) | (2.01) | (1.34) | (1.27) | |

| CF | 0.0030 | 0.0032 | 0.0048 | 0.0051 | 0.0031 | 0.0033 |

| (1.00) | (1.07) | (1.16) | (1.23) | (1.04) | (1.10) | |

| TobinQ | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | −0.0009 | −0.0009 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| (0.28) | (0.29) | (−1.07) | (−1.05) | (0.26) | (0.27) | |

| Esh | −0.0138 | −0.0130 | −0.0306 * | −0.0296 * | −0.0129 | −0.0121 |

| (−1.37) | (−1.30) | (−1.77) | (−1.71) | (−1.30) | (−1.20) | |

| Bsize | 0.0078 *** | 0.0079 *** | 0.0081 ** | 0.0084 ** | 0.0077 *** | 0.0079 *** |

| (2.93) | (2.94) | (2.01) | (2.06) | (2.87) | (2.91) | |

| Dual | −0.0011 | −0.0010 | −0.0028 | −0.0026 | −0.0012 | −0.0010 |

| (−0.63) | (−0.56) | (−0.96) | (−0.89) | (−0.66) | (−0.58) | |

| _cons | 0.1309 *** | 0.1313 *** | 0.1116 ** | 0.1123 ** | 0.1320 *** | 0.1327 *** |

| (3.46) | (3.50) | (2.14) | (2.11) | (3.52) | (3.55) | |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 1173 | 1173 | 1173 | 1173 | 1173 | 1173 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.1361 | 0.1355 | 0.1615 | 0.1578 | 0.1366 | 0.1326 |

| Stable1 | Stable2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Column (1) | Column (2) | |

| Stable | 0.0055 | −0.0019 |

| (1.02) | (−0.37) | |

| Stable2 | 0.0001 | 0.0071 |

| (0.02) | (1.44) | |

| CC | −0.0095 | −0.0111 * |

| (−1.62) | (−1.87) | |

| Lnsize | −0.0045 * | −0.0046 * |

| (−1.89) | (−1.88) | |

| Age | −0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| (−0.02) | (0.04) | |

| ROA | −0.0317 * | −0.0312 |

| (−1.65) | (−1.62) | |

| Lev | −0.0033 | −0.0034 |

| (−0.40) | (−0.42) | |

| PPE | 0.0323 ** | 0.0323 ** |

| (2.11) | (2.11) | |

| CF | 0.0047 | 0.0050 |

| (1.12) | (1.20) | |

| TobinQ | −0.0009 | −0.0008 |

| (−1.06) | (−1.03) | |

| Esh | −0.0319 * | −0.0309 * |

| (−1.84) | (−1.79) | |

| Bsize | 0.0083 ** | 0.0084 ** |

| (2.06) | (2.09) | |

| Dual | −0.0027 | −0.0026 |

| (−0.93) | (−0.89) | |

| _cons | 0.1100 ** | 0.1109 ** |

| (2.08) | (2.07) | |

| Year FE | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES |

| N | 1173 | 1173 |

| Adj−R2 | 0.1610 | 0.1647 |

| Stable1 | Stable2 | Stable1 | Stable2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eliminate Cus_Stable < 5% | Eliminate CC < 10% | Eliminate Individual Customers | Eliminate Individual Customers | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Stable | 0.0060 ** | 0.0066 *** | 0.0057 *** | 0.0057 *** |

| (2.55) | (3.38) | (3.25) | (3.26) | |

| CC | −0.0092 | −0.0092 | −0.0097 | −0.0106 * |

| (−1.37) | (−1.54) | (−1.58) | (−1.71) | |

| Lnsize | −0.0038 | −0.0060 ** | −0.0044 * | −0.0045 * |

| (−1.30) | (−2.29) | (−1.82) | (−1.84) | |

| Age | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | −0.0001 | −0.0001 |

| (0.04) | (0.18) | (−0.26) | (−0.18) | |

| ROA | −0.0462 * | −0.0388 * | −0.0350 * | −0.0340 * |

| (−1.93) | (−1.81) | (−1.78) | (−1.73) | |

| Lev | −0.0073 | −0.0012 | −0.0039 | −0.0042 |

| (−0.78) | (−0.14) | (−0.47) | (−0.51) | |

| PPE | 0.0330 * | 0.0356 ** | 0.0298 * | 0.0302 * |

| (1.89) | (2.12) | (1.92) | (1.94) | |

| CF | 0.0035 | 0.0019 | 0.0043 | 0.0045 |

| (0.73) | (0.41) | (1.00) | (1.05) | |

| TobinQ | −0.0003 | −0.0010 | −0.0009 | −0.0009 |

| (−0.32) | (−1.10) | (−1.06) | (−1.04) | |

| Esh | −0.0348 * | −0.0406 ** | −0.0315 * | −0.0307 * |

| (−1.70) | (−2.12) | (−1.82) | (−1.78) | |

| Bsize | 0.0117 ** | 0.0102 ** | 0.0083 ** | 0.0084 ** |

| (2.18) | (2.13) | (2.05) | (2.07) | |

| Dual | −0.0009 | −0.0022 | −0.0027 | −0.0025 |

| (−0.29) | (−0.68) | (−0.91) | (−0.86) | |

| _cons | 0.0863 | 0.1357 ** | 0.1103 ** | 0.1101 ** |

| (1.30) | (2.31) | (2.05) | (2.04) | |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 948 | 1017 | 1149 | 1149 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.1688 | 0.1705 | 0.1613 | 0.1633 |

| Stable = Stable1 | Stable = Stable2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before PSM | After PSM | Before PSM | After PSM | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Stable | 0.0056 *** | 0.0087 *** | 0.0054 *** | 0.0058 ** |

| (3.21) | (3.11) | (3.17) | (2.58) | |

| CC | −0.0095 | −0.0007 | −0.0104 * | −0.0087 |

| (−1.62) | (−0.08) | (−1.75) | (−1.21) | |

| Lnsize | −0.0045 * | −0.0035 | −0.0046 * | −0.0038 |

| (−1.90) | (−0.75) | (−1.92) | (−1.23) | |

| Age | −0.0000 | −0.0001 | 0.0000 | −0.0001 |

| (−0.02) | (−0.12) | (0.09) | (−0.37) | |

| ROA | −0.0317 * | −0.0173 | −0.0305 | −0.0324 |

| (−1.65) | (−0.58) | (−1.59) | (−1.25) | |

| Lev | −0.0033 | −0.0091 | −0.0035 | −0.0119 |

| (−0.40) | (−0.75) | (−0.43) | (−1.06) | |

| PPE | 0.0323 ** | 0.0289 * | 0.0327 ** | 0.0363 * |

| (2.11) | (1.66) | (2.13) | (1.94) | |

| CF | 0.0047 | 0.0057 | 0.0050 | 0.0010 |

| (1.12) | (1.12) | (1.19) | (0.16) | |

| TobinQ | −0.0009 | −0.0005 | −0.0008 | −0.0005 |

| (−1.06) | (−0.31) | (−1.04) | (−0.43) | |

| Esh | −0.0319 * | −0.0155 | −0.0311 * | −0.0065 |

| (−1.84) | (−0.70) | (−1.80) | (−0.32) | |

| Bsize | 0.0083 ** | 0.0141 *** | 0.0083 ** | 0.0112 ** |

| (2.06) | (2.84) | (2.08) | (2.00) | |

| Dual | −0.0027 | 0.0016 | −0.0026 | −0.0018 |

| (−0.93) | (0.51) | (−0.88) | (−0.51) | |

| _cons | 0.1099 ** | 0.0659 | 0.1099 ** | 0.0884 |

| (2.08) | (0.67) | (2.07) | (1.31) | |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 1173 | 628 | 1173 | 846 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.1610 | 0.1802 | 0.1626 | 0.1648 |

| Sample | Mean | SD (%) | t-Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Control | t-Value | p-Value | |||

| CC | Before PSM | 0.298 | 0.254 | 24.2 | 3.88 | 0.000 |

| After PSM | 0.298 | 0.293 | 2.4 | 0.32 | 0.749 | |

| Lnsize | Before PSM | 22.025 | 22.069 | −4.1 | −0.64 | 0.525 |

| After PSM | 22.025 | 22.073 | −4.5 | −0.63 | 0.531 | |

| Age | Before PSM | 15.321 | 15.045 | 6.1 | 0.97 | 0.333 |

| After PSM | 15.321 | 15.231 | 2.0 | 0.27 | 0.784 | |

| ROA | Before PSM | 0.046 | 0.043 | 6.5 | 1.02 | 0.307 |

| After PSM | 0.046 | 0.045 | 1.9 | 0.26 | 0.793 | |

| Lev | Before PSM | 0.470 | 0.472 | −1.0 | −0.16 | 0.877 |

| After PSM | 0.470 | 0.469 | 0.4 | 0.05 | 0.958 | |

| PPE | Before PSM | 0.065 | 0.059 | 13.7 | 2.17 | 0.030 |

| After PSM | 0.065 | 0.064 | 3.1 | 0.42 | 0.677 | |

| CF | Before PSM | 0.004 | 0.004 | −0.1 | −0.02 | 0.983 |

| After PSM | 0.004 | 0.005 | −0.8 | −0.11 | 0.913 | |

| TobinQ | Before PSM | 2.259 | 2.363 | −7.1 | −1.11 | 0.267 |

| After PSM | 2.259 | 2.118 | 9.7 | 1.53 | 0.127 | |

| Esh | Before PSM | 0.031 | 0.030 | 1.1 | 0.17 | 0.863 |

| After PSM | 0.031 | 0.025 | 6.5 | 0.93 | 0.354 | |

| Bsize | Before PSM | 2.182 | 2.184 | −1.1 | −0.17 | 0.863 |

| After PSM | 2.182 | 2.184 | −1.0 | −0.14 | 0.890 | |

| Dual | Before PSM | 0.780 | 0.798 | −4.3 | −0.69 | 0.491 |

| After PSM | 0.780 | 0.796 | −4.0 | −0.54 | 0.589 | |

| Sample | Ps R2 | LR chi2 | p > chi2 | Mean deviation | Median deviation | B |

| Before PSM | 0.021 | 30.93 | 0.001 | 6.3 | 4.3 | 35.4 * |

| After PSM | 0.004 | 3.99 | 0.970 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 14.7 |

| Sample | Mean | SD (%) | t-Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Control | t-Value | p-Value | |||

| CC | Before PSM | 0.309 | 0.233 | 43.1 | 7.44 | 0.000 |

| After PSM | 0.309 | 0.301 | 4.5 | 0.69 | 0.490 | |

| Lnsize | Before PSM | 21.974 | 22.124 | −13.7 | −2.33 | 0.020 |

| After PSM | 21.974 | 21.934 | 3.6 | 0.64 | 0.525 | |

| Age | Before PSM | 15.163 | 15.104 | 1.3 | 0.22 | 0.824 |

| After PSM | 15.163 | 14.972 | 4.2 | 0.68 | 0.499 | |

| ROA | Before PSM | 0.046 | 0.042 | 7.3 | 1.24 | 0.216 |

| After PSM | 0.046 | 0.047 | −2.0 | −0.33 | 0.745 | |

| Lev | Before PSM | 0.463 | 0.478 | −8.3 | −1.41 | 0.158 |

| After PSM | 0.463 | 0.462 | 0.8 | 0.13 | 0.895 | |

| PPE | Before PSM | 0.064 | 0.058 | 13.5 | 2.31 | 0.021 |

| After PSM | 0.064 | 0.066 | −4.9 | −0.77 | 0.441 | |

| CF | Before PSM | 0.004 | 0.005 | −0.9 | −0.15 | 0.877 |

| After PSM | 0.004 | 0.009 | −5.6 | −0.93 | 0.352 | |

| TobinQ | Before PSM | 2.350 | 2.314 | 2.4 | 0.41 | 0.682 |

| After PSM | 2.350 | 2.345 | 0.3 | 0.05 | 0.958 | |

| Esh | Before PSM | 0.032 | 0.028 | 5.3 | 0.91 | 0.363 |

| After PSM | 0.032 | 0.030 | 2.5 | 0.40 | 0.691 | |

| Bsize | Before PSM | 2.187 | 2.181 | 3.3 | 0.56 | 0.575 |

| After PSM | 2.187 | 2.193 | −2.8 | −0.47 | 0.635 | |

| Dual | Before PSM | 0.766 | 0.814 | −11.7 | −2.01 | 0.045 |

| After PSM | 0.766 | 0.764 | 0.5 | 0.07 | 0.943 | |

| Sample | Ps R2 | LR chi2 | p > chi2 | Mean deviation | Median deviation | B |

| before PSM | 0.046 | 75.03 | 0.000 | 10.1 | 7.3 | 51.4 * |

| after PSM | 0.003 | 3.94 | 0.972 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 12.1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Xin, Y.; Luo, Z.; Han, M. The Impact of Stable Customer Relationships on Enterprises’ Technological Innovation Based on the Mediating Effect of the Competitive Advantage of Enterprises. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073610

Chen Y, Xin Y, Luo Z, Han M. The Impact of Stable Customer Relationships on Enterprises’ Technological Innovation Based on the Mediating Effect of the Competitive Advantage of Enterprises. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):3610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073610

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yan, Yingying Xin, Zhengying Luo, and Min Han. 2021. "The Impact of Stable Customer Relationships on Enterprises’ Technological Innovation Based on the Mediating Effect of the Competitive Advantage of Enterprises" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073610

APA StyleChen, Y., Xin, Y., Luo, Z., & Han, M. (2021). The Impact of Stable Customer Relationships on Enterprises’ Technological Innovation Based on the Mediating Effect of the Competitive Advantage of Enterprises. Sustainability, 13(7), 3610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073610